The golf swing is a complex, coordinated motor task that couples high-velocity segmental rotations with precise club-ball interaction, demanding an integrated outlook spanning kinematics, kinetics, and neuromuscular control. Performance outcomes such as clubhead speed, launch conditions, and shot dispersion emerge from the temporal sequencing of pelvis, trunk, and upper-limb segments, the generation and transfer of angular momentum, and the modulation of external forces through ground reaction and club-shaft dynamics. Concurrently, the repetitive, high-load nature of the swing places unique mechanical stresses on the lumbar spine, shoulder, and elbow, linking technique to injury risk through patterns of joint loading, aberrant muscle activation, and limited tissue tolerance.

This article synthesizes contemporary evidence on the mechanical and physiological determinants of the golf swing mechanism. It reviews kinematic descriptors (segmental rotations, velocities, proximal-to-distal sequencing, X-factor and X-factor stretch), kinetic contributors (joint torques, ground-reaction forces, inverse-dynamics estimates of net moments and power transfer), and neuromuscular dynamics (EMG timing and magnitude, motor-program variability, and fatigue effects). Methodological considerations-motion-capture systems, force platforms, wearable inertial sensors, surface and fine-wire EMG, and computational modeling-are evaluated for their capacity to quantify swing mechanics and inform causal inference.

The review aims to bridge biomechanical insight and applied coaching by highlighting how specific mechanical patterns influence performance metrics and predispose to common injuries,proposing evidence-based refinements in technique and training. Emphasis is placed on translating laboratory findings into practical assessment and intervention strategies that respect individual anatomical and functional variability while optimizing the balance between mobility, stability, and power generation.

Conceptual Framework for Biomechanical Analysis of the Golf Swing

The framework adopts a **conceptual** stance-grounded in ideas and principles that structure measurement and interpretation-translating complex multiscale phenomena into analyzable constructs. At its core are three complementary domains: **kinematics** (segmental trajectories, orientations, temporal sequencing), **kinetics** (joint moments, ground reaction forces, club-ball interaction), and **neuromuscular dynamics** (timing, amplitude, and coordination of muscle activation). By explicitly naming these domains and their expected interactions, the framework provides a reproducible language for hypothesis formulation, experimental design, and cross-study synthesis.

Analysis proceeds through a hierarchical model that links organism,task,and surroundings constraints to performance outcomes. Key conceptual elements include:

- Constraints: anthropometrics, equipment parameters, course/environmental variables

- Control policies: motor strategies, shot intent, and variability tolerances

- Mechanical outputs: clubhead speed, impact location, and resultant ball kinematics

Measurement modalities are mapped to analytic goals so that methods align with inference strength. The following simple schema illustrates common pairings used within this conceptual architecture:

| Measurement | Primary Output | Typical Inference |

|---|---|---|

| 3D motion capture | Segment kinematics | Sequencing and timing |

| Force plate | Ground reaction forces | Load transfer and balance |

| Surface EMG | Muscle activation patterns | Neuromuscular coordination |

| Inverse dynamics / modeling | Joint moments & power | Source of energy transfer |

Operationalizing the framework supports both technique refinement and injury mitigation through targeted, hypothesis-driven interventions. Practitioners translate assessment findings into concrete coaching cues, equipment adjustments, or conditioning programs, prioritizing **modifiable risk factors** (e.g., excessive lateral bending, inadequate hip sequencing). Recommended outputs from the framework include:

- Quantified sequencing windows for swing phases

- Thresholds for asymmetry and load exposure

- EMG-guided retraining protocols for timing deficits

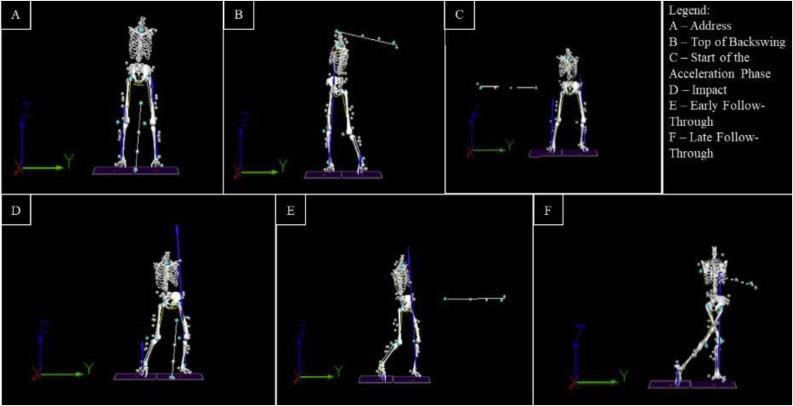

Kinematic Patterns and Phase-Specific Motion Analysis in the Golf Swing

The coordinated motion of the swing is best characterized as a multisegmental, proximal-to-distal kinematic chain in which the pelvis, thorax, upper limbs and club operate with temporally staggered velocity peaks. Empirical patterns show that peak angular velocities progress from the hips to the shoulders and finally to the wrists/clubhead, producing an efficient transfer of mechanical energy.Emphasis should be placed on the timing of intersegmental rotations-frequently enough quantified as **pelvis-to-thorax separation (X-factor)** and its rate of change-as small shifts in these variables yield disproportionately large effects on clubhead speed and shot dispersion.

Phase-specific analysis reveals distinct kinematic signatures for each nominal subphase of the swing. Key markers used in clinical and performance assessments include segmental angular displacement, instantaneous angular velocity, and relative phase between adjacent segments. Typical markers include:

- Early backswing: controlled trunk rotation with minimal lateral head displacement.

- Top/transition: maximal pelvis-thorax separation and initiation of proximal-to-distal sequencing.

- Downswing to impact: rapid increase in shoulder and wrist angular velocity; near-simultaneous deceleration of the torso.

- Follow-through: energy dissipation through controlled deceleration and reorientation of the torso and lead limb.

These markers provide objective criteria to differentiate efficient, repeatable swings from compensatory or injury-prone patterns.

Quantitative comparison across phases can be summarized in compact form to aid practitioner decision-making. The table below illustrates representative kinematic benchmarks drawn from cohort analyses and expert-performance archetypes. Table cells contain short, clinically useful magnitudes and timing references suitable for use in coaching dashboards and motion-capture reports.

| Phase | Representative metric | Timing (relative to impact) |

|---|---|---|

| Top of backswing | X‑factor ≈ 40° (±10°) | −200 to −100 ms |

| Max pelvis angular velocity | ~600°/s | −120 to −60 ms |

| Peak clubhead angular velocity | >3000°/s (elite) | ~0 ms (impact) |

Translating phase-specific kinematics into practice requires attention to both absolute values and their temporal relationships. Coaches and clinicians should prioritize measurement of **relative timing** (e.g.,delay between pelvis and thorax peak velocities) as much as magnitude,since temporal errors commonly underlie loss of power and increased joint load. For reproducibility, adopt standardized capture protocols (sampling ≥200 Hz), apply clear anatomical landmarks for segment definitions, and track intra-subject variability across trials to distinguish systematic deficits from normal motor noise. These strategies enable targeted interventions that preserve performance while reducing musculoskeletal risk.

Kinetic Determinants of Power Transfer: Ground Reaction Forces, Joint Torques, and Clubhead Velocity

Power generation in the swing is fundamentally a product of force transmission from the feet through the kinetic chain to the clubhead. Ground reaction forces (GRFs) provide the primary external impulse; their magnitude, direction, and temporal profile determine how effectively lower‑limb effort can be converted into rotational and translational energy of the pelvis and trunk. The term kinetic itself denotes a relation to motion (see The Free Dictionary definition of “kinetic”), and in the golf context this motion is shaped by vectorial GRF components-vertical, anterior‑posterior and medial‑lateral-and the rate at which they are produced (rate of force progress, RFD). High peak GRFs without appropriate timing yield inefficient energy transfer and can elevate injury risk.

Joint torques act as the internal drivers that convert GRF‑derived impulses into segmental angular accelerations. Effective power transfer depends on a proximal‑to‑distal sequencing of torque production and release: powerful hip extension and rotation precede trunk torque,which in turn primes shoulder and forearm torques before final wrist release. Key biomechanical contributors include:

- force coupling at the feet: coordinated bilateral GRF application and weight shift.

- Hip torque generation: rapid hip extension and external rotation to initiate pelvis acceleration.

- Trunk rotational torque: eccentric control on the downswing and concentric acceleration through impact.

- Distal segment release: timed forearm/hand torques that maximize clubhead angular velocity.

| Metric | Typical Range | Relation to Clubhead Speed |

|---|---|---|

| Peak vertical GRF | 1.2-2.5 × body weight | Higher peaks → greater impulse potential |

| Peak hip torque | 120-300 N·m | Drives pelvis rotation and trunk power |

| Timing offset (pelvis → trunk) | 20-60 ms | Short, consistent offsets optimize transfer |

| Estimated clubhead velocity | 30-45 m/s | Outcome of integrated kinetics and timing |

From an optimization perspective, interventions should target both magnitude and timing: increase RFD through ballistic and eccentric training, enhance hip and trunk torque capacity with strength/power protocols, and refine sequencing via motor learning drills and biofeedback (force plates, inertial sensors). Emphasis on controlled eccentric braking of proximal segments reduces injury risk while preserving elastic energy transfer. Practically, coaches should monitor a small set of kinetic markers-peak GRF, pelvic angular velocity, inter‑segmental timing-and use them to prescribe targeted technical and conditioning adaptations that maximize clubhead velocity while minimizing maladaptive loads.

Neuromuscular Coordination and Muscle Activation Strategies: Timing, Sequencing, and Fatigue Effects

Efficient power transfer in the golf swing is underpinned by a reproducible pattern of muscle activations that follows a **proximal-to-distal sequencing**: lower limb and hip extensors generate the initial ground-reaction impulse, the pelvis and lumbar rotators convert and amplify that impulse, and the shoulder, forearm, and wrist musculature fine-tune clubhead velocity and orientation.Electromyographic (EMG) studies consistently show phased onsets rather than simultaneous bursts; this temporal staggering reduces inertial losses and maximizes segmental angular velocity. variability in timing-both intra- and inter-player-explains a notable portion of ballistic outcome variance, making precise timing as critical as peak force capacity for repeatable ball launch conditions.

Neuromuscular control strategies combine feedforward anticipatory activation with rapid feedback corrections. Prior to ball contact, golfers adopt **anticipatory postural adjustments** that pre-activate trunk stabilizers and hip abductors to create a stiff base for rotational torque. Concurrently,fine motor muscles in the forearms employ short-latency reflexes to correct clubface orientation during the late swing. Training and analysis should therefore emphasize both: (a) feedforward drills to tune pre-activation patterns and (b) reactive perturbation exercises to sharpen short-latency responses. Recommended measurement modalities include high-density EMG, inertial measurement units (IMUs), and synchronized force-plate recordings to disambiguate anticipatory versus reactive components.

Fatigue systematically alters sequencing and increases injury risk by delaying onset latencies and elevating co-contraction across antagonistic muscle groups. Under fatigue, the typical temporal gradient compresses-proximal activations become less dominant while distal muscles compensate with increased and prolonged activity, which reduces clubhead speed and elevates shear loads on the lumbar spine and elbow.The table below synthesizes representative onset windows for a prototypical right-handed golfer relative to ball impact; these values serve as a diagnostic framework for identifying sequencing degradations under fatigue or load:

| Segment | Typical Onset (ms before impact) |

|---|---|

| Lead leg/ground reaction | ~200 ms |

| Pelvis rotation | ~120 ms |

| Trunk (lumbar) rotation | ~90 ms |

| Shoulder/arm drive | ~40 ms |

| Wrist release | ~5 ms |

To mitigate fatigue-related deterioration and enhance reproducibility,interventions should prioritize neuromuscular resiliency: progressive plyometrics to increase rate of force development,core stability training to preserve intersegmental timing,and task-specific endurance sets that replicate competitive repetition. Practical training drills include resisted hip-drive repetitions, truncated-swing tempo work that emphasizes onset timing, and perturbation-based balance tasks to strengthen anticipatory control. Emphasize objective monitoring (EMG thresholds, time-to-peak metrics, and IMU-derived angular velocity profiles) and adopt load-management rules that preserve the temporal architecture of the swing; preserving timing often yields greater performance gains than increasing isolated maximal force alone.

Stability, Mobility, and Segmental Coupling: Implications for Technique Optimization and Injury Prevention

Effective swing mechanics arise from a calibrated balance between **stability** (the capacity to control joint position under load) and **mobility** (the available, coordinated range of motion). In golf, spinal-pelvic stability provides the foundation for reproducible club delivery while segmental mobility-especially of the hips, thoracic spine, and shoulders-permits the large rotational excursions required for clubhead speed. When stability is insufficient,compensatory mobility demands increase at adjacent segments,elevating shear and torsional loads; conversely,excessive mobility without dynamic control degrades kinetic link efficiency and reduces energy transfer. Quantifying these constructs in both static and dynamic contexts is therefore essential to target technique modifications and training interventions with precision.

The motor strategy that optimizes performance is characterized by efficient **proximal-to-distal coupling**, where energy generated by the larger, proximal segments is sequentially transferred to distal segments with minimal dissipative loss. Key practical targets for technical optimization include:

- Temporal sequencing: refine the timing of pelvis rotation relative to thoracic unwind to maximize angular velocity gradients.

- Segmental stiffness modulation: increase dynamic stiffness in the lead leg and lumbar-pelvic complex during transition to stabilize the proximal base of support.

- Controlled distal release: preserve wrist hinge and forearm supination timing so that distal acceleration occurs as an inevitable result of, not in spite of, proximal impulses.

To mitigate injury risk while enhancing performance, targeted interventions should align with observed biomechanical deficits. The table below summarizes concise training focuses and their mechanistic rationales; integrate these into individualized programs based on assessment findings.

| Target | Training focus | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Pelvis / hips | Single-leg stability + hip rotational strength | Reduces lumbar compensations; improves force transfer |

| Thoracic spine | Rotational mobility + motor control drills | Facilitates separation between pelvis and shoulders |

| Scapulo‑thoracic complex | Endurance and dynamic control of scapular retractors | Maintains safe shoulder kinematics during follow-through |

Implementing an evidence-informed assessment battery-combining **3D kinematics**, IMU-derived segmental timing, force‑plate ground-reaction metrics, and selective clinical screens (e.g., single-leg squat, thoracic rotation test, hip internal rotation assessment)-permits targeted coaching cues and progressive corrective exercise. Monitoring should prioritize temporal coupling indices (e.g., pelvis-to-thorax peak velocity lag), ground-reaction force symmetry, and muscle activation patterns that indicate feedforward stability. embed these corrective emphases within a **periodized** framework that alternates technical, strength, and mobility phases to consolidate motor learning while reducing cumulative tissue load.

Influence of Anthropometry and Equipment Interaction on Swing Mechanics: Personalized Assessment and Adjustments

Inter-individual differences in body size, limb proportions, and segmental mass distribution systematically modulate the kinematic patterns and loading profiles observed in the golf swing. Longer forearms and thoracic height alter effective swing radius and clubhead linear velocity for a given angular velocity, while a higher trunk-to-pelvis flexibility ratio changes relative timing of upper- and lower-body rotation. These morphological factors influence the location of the instantaneous center of rotation, moment arms of primary rotators, and propensity for compensatory movement patterns; consequently, **anthropometry** cannot be treated as noise but rather as a primary determinant of optimal movement solution and injury risk profile.

Comprehensive personalization requires objective, repeatable assessment combining morphological and dynamic measures. Recommended components include:

- Three-dimensional motion capture (marker or markerless) for segment kinematics and intersegmental timing.

- Force plate analysis to quantify weight transfer and ground-reaction sequencing.

- Club-embedded sensors for clubhead trajectory, face orientation, and temporal events.

- Clinical anthropometry (segment lengths, limb circumferences) and joint range-of-motion testing.

This multimodal protocol enables mapping of morphological constraints to specific kinetic sequencing deviations, supporting evidence-based equipment and technique adjustments.

Equipment interaction should be treated as an extension of the athlete’s biomechanics: shaft flex, length, lie angle, grip size, and clubhead mass distribution modify inertial demands and sensory feedback, thus reshaping motor strategies. The table below summarizes typical anthropometric trends and corresponding fitting priorities to guide initial interventions.

| Anthropometric Trait | Common Biomechanical Effect | Fitting Priority |

|---|---|---|

| taller stature / long arms | increased swing radius; timing shift | Club length & shaft stiffness |

| Shorter torso / limited rotation | reduced shoulder turn; early release | Shorter shaft,upright lie |

| High body mass / proximal mass | Altered center of mass displacement | Head weight distribution & grip size |

Optimization is iterative: data-driven adjustment of equipment should be paired with targeted neuromuscular training to shift movement patterns within the athlete’s morphological envelope. Prioritize interventions that reduce pathological joint loads while preserving or enhancing kinetic sequencing (proximal-to-distal transfer). Clinicians and fitters should adopt a decision-tree approach-assess, adjust one parameter, re-evaluate kinematics/kinetics-and document outcomes. Emphasis on **individual response** rather than population norms yields the greatest gains in performance and injury mitigation.

evidence-Based Training, Rehabilitation, and Motor Learning Interventions for Performance Enhancement and Safe return to Play

Rehabilitation and conditioning programs should align with biomechanical risk factors identified in swing analysis and follow the principles of specificity and progressive overload. Emphasis is placed on restoring eccentric control of the shoulder girdle and scapular stabilizers, concentric and eccentric strength of hip external rotators, and rate-of-force development in the trunk and lower limbs. Interventions that combine neuromuscular re-education with targeted strength and power work-such as slow eccentric loading followed by ballistic hip-rotation drills-have the greatest translational potential for swing mechanics. Clinicians should integrate objective load management (e.g., sessional volume, force-time characteristics) with patient-reported pain and function to guide progression.

Motor learning approaches must supplement tissue rehabilitation to produce durable technical change. A contemporary evidence-based framework favors an external focus of attention, variable practice schedules, and constrained-task training to promote adaptability under competitive constraints. Augmented feedback should be carefully timed: provide summary knowlege of results (KR) to foster self-regulation and intermittent knowledge of performance (KP) for complex kinematic errors. Practical prescriptions include:

- Short, high-quality blocks of variable practice (e.g., alternating club types and target distances) to enhance transfer.

- Use of external cues (e.g., “push the ground away” or “rotate chest toward target”) rather than internal muscle cues.

- Progressive reduction of augmented feedback to encourage retention and self-monitoring.

- Integration of dual-task drills late in rehabilitation to restore attentional robustness under pressure.

Return-to-play progression should be criterion-based and staged,integrating objective biomechanical and clinical milestones.The table below summarizes a concise phased model with representative metrics used to clear progression between stages.

| Phase | Primary Goal | Representative Objective Metrics |

|---|---|---|

| 1 – Restore | Pain-free ROM, basic strength | ROM within 90% contralateral; pain ≤2/10 |

| 2 - Reinforce | Eccentric control, load tolerance | Eccentric rotator capacity ≥70% baseline |

| 3 – Integrate | Dynamic swing patterns, power | Clubhead speed within 90% pre-injury; trunk-pelvis dissociation restored |

| 4 – Return | Competition readiness and resilience | Sustained performance across simulated rounds; no flares |

Successful implementation requires interdisciplinary coordination and ongoing monitoring. Combine kinematic benchmarks (e.g., pelvis-trunk separation angles), kinetic outputs (ground reaction force symmetry, peak rate of force development), and neuromuscular markers (EMG timing or validated functional tests) to quantify recovery. Employ wearable sensors and video-based motion capture for regular re-assessment and to individualize thresholds; adjust training loads when metrics indicate reduced tolerance or technique regressions.Ultimately, a data-driven, staged approach that couples targeted tissue loading with motor learning strategies minimizes reinjury risk while maximizing the likelihood of reproducible, high-performance swings.

Q&A

note on search results: the provided web search results did not return sources relevant to golf-swing biomechanics. The Q&A below is therefore based on contemporary biomechanical principles and common methodologies in the sports-bioengineering literature rather than the returned links.

Q: What is meant by “biomechanical analysis” of the golf swing mechanism?

A: Biomechanical analysis applies principles of mechanics, anatomy and neurophysiology to quantify the motion, forces and muscle actions during the golf swing. It comprises kinematic description (displacement, velocity, acceleration of body segments and the club), kinetic analysis (forces and moments, e.g., ground reaction forces, joint moments, club-ball interaction), and neuromuscular analysis (muscle activation patterns, timing, coordination). The objective is to explain performance determinants (e.g., clubhead speed, accuracy), identify injury mechanisms, and provide evidence-based guidance for technique, training and equipment design.

Q: How do kinematics and kinetics differ and why are both necessary?

A: Kinematics describes “how” segments and the club move (position, orientation, linear/angular velocities and accelerations) without reference to forces. Kinetics explains “why” those motions occur by quantifying forces and moments (external forces, joint reaction forces, joint moments, and power). Both are necessary as identical kinematics can arise from different force-generation strategies; understanding both allows inference about muscle function, energy transfer, and injury risk.

Q: What are the key kinematic variables in golf-swing research?

A: Typical kinematic variables include clubhead linear and angular velocity, clubhead path and face orientation at impact, pelvis and thorax rotation angles and angular velocities, shoulder and hip separation or X-factor, trunk lateral flexion and tilt, lead and trail knee and ankle angles, center-of-mass (CoM) trajectory, and timing of peak segmental velocities (kinematic sequence).

Q: What kinetic measures are most informative for the golf swing?

A: Ground reaction forces (vertical, anterior-posterior, mediolateral), center-of-pressure (CoP) displacement, joint moments and powers (particularly at hips, trunk and shoulders), external loads transmitted through the wrist and elbow at impact, and impulse measures. Joint reaction forces and inverse-dynamics-derived moments help attribute loads to specific structures relevant for performance and injury risk.

Q: What is the “kinematic sequence” and why is it critically important?

A: The kinematic sequence describes the temporal ordering of peak angular velocities of linked body segments (typically pelvis → thorax → upper arm → club). An efficient proximal-to-distal sequence maximizes energy transfer and clubhead speed while minimizing compensatory stresses. Deviations (e.g., early arm acceleration or delayed trunk rotation) can reduce performance or increase joint loads.

Q: Which neuromuscular dynamics are critical in the swing?

A: Key aspects include preprogrammed activation patterns (feedforward), timing and amplitude of muscle activations (especially trunk rotators, hip muscles, abdominal wall, gluteals, scapular stabilizers, wrist flexors/extensors), muscle coordination or synergies, rate of force development, and reflexive responses to perturbations. Electromyography (EMG) studies reveal phasic bursts timed to prepare, initiate and accelerate the swing while controlling deceleration and impact forces.

Q: What measurement technologies are commonly used?

A: Optical motion capture (passive or active markers), inertial measurement units (IMUs), high-speed videography, force plates (single or dual), pressure insoles, 3D electromagnetic trackers, surface EMG, radar/laser devices for clubhead speed, instrumented clubs, and ball launch monitors. Each modality has trade-offs in accuracy, ecological validity and portability.

Q: What sampling rates and data-processing practices are recommended?

A: Use sufficiently high sampling frequencies to capture fast rotational events: motion capture 200-500 Hz (higher for professional swings), force plates and EMG 1000-2000 Hz. Apply appropriate filtering (e.g., low-pass Butterworth for kinematics with cutoffs determined by residual analysis; band-pass and rectification for EMG with normalization to maximum voluntary contractions). Report all processing parameters for reproducibility.

Q: How is inverse dynamics applied to the golf swing?

A: Inverse dynamics uses measured kinematics and external forces (e.g., GRF) with body-segment inertial properties to compute net joint moments and powers. Multibody models (e.g., linked rigid segments) are constructed, and equations of motion are solved in proximal-to-distal or distal-to-proximal fashion. Careful segment parameterization, coordinate-system definition and filtering are essential to avoid artifacts.

Q: What are typical sources of measurement error and bias?

A: Marker placement errors, soft-tissue artifact, coordinate-system inconsistency, camera occlusion, inadequate sampling rates, wrong filtering choices, inaccurate segment inertial estimates, electrode cross-talk in EMG, and laboratory constraints that alter natural swing behaviour (e.g., hitting into a net). Reporting reliability metrics and performing sensitivity analyses helps quantify these effects.Q: Which joints and tissues are most at risk of injury in golfers?

A: Commonly affected regions include the lumbar spine (low-back pain and stress from repeated rotation and compressive/shear loads), leading wrist (impact and extension/ulnar deviation loading), medial elbow (valgus overload), and shoulder (rotator-cuff and labral pathology). Risk factors include poor sequencing, excessive lumbar lateral flexion/extension, high axial rotation under large compressive loads, insufficient hip mobility, and abrupt deceleration strategies.Q: How can biomechanical analysis inform injury prevention?

A: By identifying high-risk movement patterns (e.g.,excessive anterior trunk tilt,abrupt lateral bending at impact,early arm-dominant swings),quantifying joint loads,and correlating loading profiles with injury incidence,biomechanics provides targeted interventions: technique modification to alter sequencing,off-season and prehabilitation programs to address mobility or strength deficits,equipment adjustments,and workload management.

Q: what technique refinements are supported by biomechanical evidence to increase clubhead speed and consistency?

A: Evidence supports optimizing proximal-to-distal sequencing (timed pelvis rotation followed by thorax and arms),maximizing hip-shoulder separation (within tissue tolerance) to store elastic energy,minimizing unnecessary vertical motion of com,and ensuring efficient energy transfer through appropriate wrist hinge and release timing. Strength and power training (hip and trunk rotational power, anti-rotational core strength) combined with motor learning approaches (augmented feedback, variable practice) enhance transfer to swing performance.

Q: What role do strength, power and mobility training play?

A: Strength and power in the hips, trunk and lower limbs increase the capacity to generate ground reaction forces and rotational torque. Rate of force development and rotational power are particularly relevant. Mobility in hips and thoracic spine facilitates optimal separation and rotation sequence. Training must be specific, progressive, and integrated with technical practice to avoid maladaptive movement patterns.

Q: How should researchers design studies in golf-swing biomechanics?

A: Use adequate sample sizes powered for primary outcomes, include representative participant groups (skill level, sex, age), control for club and ball characteristics, standardize warm-up and fatigue states, employ high-fidelity measurement systems, report reliability (ICC, SEM), use appropriate statistical models for repeated measures (mixed models), and correct for multiple comparisons. Where possible, include ecological-valid tasks (full swing with ball flight) and longitudinal designs to infer causality.

Q: What statistical and reliability metrics are important to report?

A: Intraclass correlation coefficients (ICC) and standard error of measurement (SEM) for repeated-measures reliability,effect sizes (Cohen’s d or partial eta-squared),confidence intervals,appropriate p-values with corrections for multiple tests,and,for predictive models,cross-validation metrics (R^2,RMSE). Time-series analyses (e.g., Statistical Parametric Mapping) are useful for continuous kinematic/EMG comparisons.

Q: What limitations should be acknowledged in biomechanical golf-swing studies?

A: Laboratory constraints can reduce ecological validity (differences in ball flight, psychological pressure), small or homogeneous samples limit generalizability, marker-based systems have soft-tissue artifact, inverse dynamics provide net joint moments but not individual muscle forces without musculoskeletal modeling, and cross-sectional designs cannot establish adaptation or causality.

Q: How can wearable sensors and machine learning change future practice?

A: Wearables (imus, instrumented grips) enable field-based, high-volume monitoring and real-world feedback.Machine-learning models can classify movement patterns, predict performance outcomes and injury risk, and provide individualized coaching cues. Validation against gold-standard lab systems and interpretability of models remain important.Q: What are practical, evidence-based takeaways for coaches and clinicians?

A: Assess and emphasize the kinematic sequence (proximal-to-distal), prioritize mobility (thoracic rotation, hip internal/external rotation) and strength/power (hip, trunk, lower limb), monitor and limit harmful loading patterns (excessive lumbar shear/rotation), use objective feedback (video, launch monitors, force/pressure data) but integrate it with motor-learning principles, and individualize interventions considering player anatomy, history, and goals.

Q: What ethical considerations apply to biomechanical evaluations of golfers?

A: Ensure informed consent, protect participant privacy (especially video/biometric data), disclose potential risks (e.g., fatigue, minor injury), avoid coercive recruitment of vulnerable populations, and report conflicts of interest (e.g., industry-funded equipment studies). For applied settings, use biomechanical data responsibly in return-to-play decisions.

Q: What are promising areas for future research?

A: High-fidelity musculoskeletal models to estimate individual muscle forces and tissue stresses; longitudinal studies linking biomechanical markers to injury incidence and performance change; real-world validation of wearable sensors and augmented-reality feedback; individualized optimization of technique accounting for anthropometry and tissue tolerance; and integrating biomechanics with neuroscience to study motor learning and adaptation under competitive pressure.

Q: How should clinicians interpret EMG data in golf studies?

A: EMG provides relative timing and amplitude of muscle activation but is influenced by electrode placement, cross-talk and normalization method. Use EMG mainly to infer temporal coordination and relative activity changes across conditions, normalize to a standard (e.g., MVC) for amplitude comparisons, and avoid overinterpreting absolute magnitudes as direct measures of force.

Q: Are there common misconceptions about biomechanics of the golf swing?

A: Yes. Examples: (1) There is a single “correct” swing-biomechanics support multiple effective strategies tailored to individual anatomy and skill. (2) Greater rotation always equals better performance-excessive rotation without strength/mobility can increase injury risk.(3) Onyl professional-level mechanics matter-amateur-specific constraints should inform coaching. Biomechanics should inform, not dictate, technique.

Q: Where can readers find authoritative literature on this topic?

A: Peer-reviewed journals such as Journal of Biomechanics, Sports biomechanics, Journal of applied Biomechanics, Journal of Sports Sciences and Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise publish relevant empirical and review articles. Textbooks on sport biomechanics and musculoskeletal modeling provide foundational methods. (Note: consult institutional access or databases like PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science for current studies.)

If you would like, I can generate a shorter Q&A targeted to clinicians or coaches, provide references to recent peer-reviewed studies, or produce an annotated reading list tailored to a specific subtopic (e.g., low-back injury mechanisms, wearable-sensor validation, or kinematic-sequence optimization).

the biomechanical analysis of the golf swing-integrating kinematic description, kinetic quantification, and neuromuscular characterization-offers a coherent framework for understanding performance determinants and injury mechanisms. Synthesizing motion-capture kinematics with force- and torque-based kinetics and with muscle activation patterns permits identification of efficient movement strategies (e.g., optimal sequencing, segmental energy transfer) as well as mechanically deleterious patterns (e.g., excessive lumbar shear, poor proximal-to-distal timing).such integrative insight can directly inform evidence-based technique refinement, individualized training prescriptions, equipment selection, and targeted rehabilitation strategies designed to enhance performance while mitigating load-related injury risk.Practically, coaches and clinicians should translate biomechanical findings into actionable interventions that respect athlete variability: emphasize reproducible swing sequences that maximize energy transfer, strengthen and condition muscles that stabilize the lumbopelvic-shoulder complex, and progressively load tissues to build resilience. Technology-ranging from portable inertial sensors and force platforms to subject-specific musculoskeletal models-can facilitate objective assessment in both laboratory and field settings, provided users remain attentive to measurement validity and ecological relevance.

Methodologically, researchers should prioritize longitudinal, ecologically valid studies that combine high-fidelity measurement with applied outcomes (accuracy, distance, injury incidence). Advances in individualized computational modeling, real-world wearable sensing, and machine-learning analyses hold promise to elucidate inter-individual differences and to predict both performance adaptations and injury risk. future work should also address underexplored areas such as neuromotor control under fatigue, developmental biomechanics across youth athletes, and the interaction of equipment design with human movement strategies.

limitations of the current literature-predominantly small-sample, cross-sectional, and laboratory-constrained studies-temper the immediacy of some translational recommendations. Consequently, the field benefits from interdisciplinary collaboration among biomechanists, sport scientists, clinicians, engineers, and coaches, to ensure that research priorities align with practical needs and that interventions are both scientifically grounded and contextually feasible.

ultimately, a rigorous, integrative biomechanics approach provides a principled pathway to optimize golf-swing technique and safeguard athlete health. Continued dialog between empirical research and applied practice will be essential to translate mechanistic knowledge into measurable gains in performance and reductions in injury burden.Note: the supplied web search results did not contain material relevant to this topic and were thus not incorporated into the above synthesis.

Biomechanical Analysis of the Golf Swing Mechanism

Note: the web search results provided with the request did not include golf-specific sources, so the content below synthesizes established biomechanics and kinematics principles, motion-capture practice, and applied coaching insights to produce an evidence-informed guide to the golf swing.

Why biomechanical analysis matters for the golf swing

Modern golf performance depends on converting coordinated body movement into efficient clubhead speed and accurate clubface orientation at impact. A biomechanical analysis breaks the swing into measurable components-joint angles,angular velocity,ground reaction forces,timing,and energy transfer-so you can systematically diagnose faults and gain repeatable improvements in distance and accuracy.

- Objective feedback: Use motion-capture or launch monitor data to quantify swing mechanics rather than relying on feel alone.

- Kinetic chain optimization: Identify how energy transfers from the ground through the legs, hips, torso, arms, and into the club.

- Injury prevention: Correct harmful loading patterns (e.g., excessive lumbar shear) while improving performance.

Core components of the golf swing mechanism (biomechanical breakdown)

Grip and wrist mechanics

The grip influences clubface control and the wrist hinge pattern. Key biomechanical points:

- Grip pressure should be firm but relaxed-excessive tension reduces wrist speed and timing.

- Wrist hinge (cocking) during the backswing creates stored angular momentum; timely unhinging through impact generates clubhead speed.

- Lead wrist (left for a right-handed golfer) dorsal/volar angles affect dynamic loft and face rotation at impact.

Stance, posture, and alignment

Proper setup establishes the body’s ability to rotate and produce ground reaction forces:

- Neutral spinal tilt with slight knee flex preserves range of motion and reduces low-back stress.

- Shoulder and hip alignment relative to target defines the swing plane and initial path of the club.

- Ball position affects launch angle and spin; driver typically more forward, irons more centralized.

Rotation, separation, and the X-factor

The X-factor-torso rotation relative to pelvis rotation-creates elastic energy in the obliques and lumbar fascia:

- Greater separation (larger X-factor) typically increases torque potential and clubhead speed, but must be balanced with mobility and control.

- Timing of pelvis rotation (lead with hips through downswing) is critical for transferring energy to the upper body and club.

Ground reaction forces and the kinetic chain

The swing is a ground-driven activity. Force production and timing are major determinants of distance:

- Vertical and horizontal ground reaction forces (measured on force plates) reveal how the lower body initiates power.

- A strong and timely push off the trail side followed by lead-side stabilization helps create efficient weight shift and angular acceleration.

Clubhead speed,swing plane,and impact mechanics

Clubhead speed and face orientation at impact dictate ball speed and dispersion:

- Maximizing clubhead speed requires coordinated segmental sequencing-proximal segments accelerate first (hips → torso → arms → club).

- Maintaining the desired swing plane reduces face rotation and unwanted shot shapes.

- Dynamic loft and angle of attack at impact govern launch angle and spin; TrackMan/FlightScope data can refine these metrics.

Biomechanical metrics to measure in swing analysis

- Clubhead speed (mph or m/s)

- Ball speed and smash factor

- Launch angle and spin rate

- Hip and shoulder rotation angles and angular velocities

- X-factor and X-factor stretch

- Ground reaction forces (N) and force vector timing

- Segmental sequencing and time to peak angular velocity

- Center of pressure (COP) movement under feet

tools and technologies for biomechanical analysis

From classroom to elite labs, different tools provide different resolution and portability:

- Motion capture systems: Optical systems (marker-based) provide high-fidelity kinematics for joint angles and segment velocities.

- High-speed video: Accessible; good for frame-by-frame mechanics and face angle visualization.

- Inertial Measurement Units (IMUs): Wearable sensors useful for on-course monitoring of swing tempo and rotational rates.

- Force plates: Measure ground reaction forces and weight-shift timing for kinetic chain mapping.

- Launch monitors (TrackMan,FlightScope): Provide ball flight metrics-launch angle,spin,clubhead speed,angle of attack.

WordPress-styled speedy comparison table

| Tool | Best for | portability |

|---|---|---|

| Motion capture | Detailed kinematics | Low |

| High-speed video | Face & plane analysis | High |

| IMUs | On-course rotational metrics | Very High |

| Force plates | Kinetic chain & GRF | Low |

| Launch monitor | Ball flight & impact | High |

Common biomechanical faults,causes,and fixes

| Fault | Biomechanical cause | Practical fix |

|---|---|---|

| Early extension | hip extension/loss of posture in downswing | Hip hinge drills,posture mirror checks |

| Over-rotation of upper body | excessive torso rotation without hip lead | Hip rotation drills,tempo training |

| Loss of lag | Premature wrist uncocking | Hold-the-**** drill,slow motion repeat |

| Slice | Open clubface and outside-in swing path | Face control practice,inside-out path drills |

Practical drills and training recommendations

Use these drills to convert biomechanical insight into repeatable skill:

- Separation drill: practice initiating the downswing with a small hip bump toward the target while maintaining shoulder coil to feel X-factor release.

- Hold-the-**** drill: Swing slowly and keep wrist hinge until just before impact to train lag.

- Step-through drill: Begin with normal setup, then step with lead foot through impact to emphasize weight transfer and lead-side stabilization.

- Force-plate mimic drill: Push off the trail foot and hold a stable lead side for a count to learn pre-impact force distribution.

- Tempo metronome: Use a metronome (e.g.,3:1 backswing:downswing rhythm) to stabilize timing and sequencing.

case study: Translating biomechanics into performance gains

Player A: recreational right-handed golfer struggling with distance and leftward misses.A biomechanical assessment revealed:

- Limited pelvis rotation and premature upper-body rotation (small X-factor)

- Low vertical ground reaction impulse off the trail foot

- Early wrist uncock in downswing

Intervention and results:

- 6-week program emphasizing hip mobility, resisted hip-turn drills, and hold-the-**** repetitions.

- On-range practice with an IMU to monitor rotation rates and a launch monitor for ball speed.

- Outcome: Improved pelvis rotation allowed greater X-factor stretch; better lag increased measured clubhead speed; more consistent strike reduced dispersion.

Key takeaway: targeted biomechanical interventions (mobility + timing drills) created measurable performance improvements without changing the player’s natural style.

Programming and periodization for swing improvement

Integrate biomechanics into a training calendar:

- Phase 1 - Mobility and control (4-6 weeks): Build hip, thoracic, and ankle mobility; stabilize spine and core.

- Phase 2 – Strength and power (6-8 weeks): Add rotational medicine ball throws, single-leg strength, and explosive hip extension work.

- Phase 3 – Skill integration (ongoing): Combine drills with on-course practice and objective measurement (launch monitor/IMU) to track transfer.

How to structure a biomechanical swing analysis session

- Warm-up and baseline setup checks (posture, ball position).

- Collect high-speed video from face-on and down-the-line plus launch monitor data for several swings.

- If available, run motion-capture or IMUs to capture joint angles and angular velocity, and force plates for GRF data.

- Analyze segmental sequencing: time-to-peak angular velocity for hips, torso, lead arm, and club.

- Prescribe targeted drills and measurable goals (e.g., increase clubhead speed by X mph or reduce side spin by Y rpm).

- Re-test after a defined training period to quantify progress.

SEO-focused on-page tips for golf coaches and content creators

- Use primary keywords naturally: “golf swing biomechanics”,”golf swing analysis”,”clubhead speed”,”X-factor”,and “ground reaction force”.

- Include long-tail phrases: “how to increase clubhead speed with hip rotation”, “biomechanical drills to stop early extension”.

- Add alt text to images describing biomechanical concepts (e.g., “lead hip rotation during golf downswing”).

- Link to reputable external sources when citing studies (journals,university labs) and create internal links to related content like drills and case studies.

- Use structured data (JSON-LD) for articles and videos demonstrating drills to improve search visibility.

First-hand coaching tips from biomechanical practice

- Measure before you change: capture video or launch data to ensure the fix improves the metric you care about.

- Progress small and specific: changing one variable at a time (tempo, hip rotation, wrist hinge) improves motor learning.

- keep cues simple: physical feedback (impact tape, face markers) often beats complex verbal cues.

- Balance performance and safety: maximize distance within the athlete’s mobility and tolerance to avoid chronic stress injuries.

Further reading and tools to explore

- Search for peer-reviewed studies on “X-factor and golf swing” and “ground reaction forces golf swing” for deeper evidence.

- Consider tools used by practitioners: TrackMan/FlightScope, K-Vest, Vicon motion capture, and force plates for lab-level diagnostics.

- follow biomechanists and applied sports scientists who publish on rotational sports biomechanics for transferable frameworks.

Use the drill library above and a consistent measurement plan to translate biomechanical insight into repeatable ball striking. For coaches: combine objective metrics with simple cues to accelerate player learning and track progress over time.