Search results returned items unrelated to the topic (retail listings for dancewear), so the following introduction is composed from disciplinary knowledge of biomechanics, motor control, and sports science.

Introduction

The golf swing is a complex, high-velocity, multi-segmental motor skill that requires precise spatiotemporal coordination of the whole body to optimize clubhead trajectory, maximize ball speed, and achieve shot accuracy. From an applied biomechanics perspective, the swing represents an archetypal example of coordinated kinetic and kinematic chaining in which energy is generated, transferred, and dissipated across connected segments-from the lower limbs and pelvis through the trunk and upper extremity to the club. Small alterations in segmental sequencing, joint moments, or neuromuscular timing can have disproportionate effects on performance outcomes and on the mechanical loads experienced by vulnerable tissues, notably the lumbar spine, shoulder, elbow, and wrist.This article synthesizes contemporary evidence on the kinematics,kinetics,and neuromuscular dynamics that underlie effective and safe golf-swing technique. Kinematic analyses-using three-dimensional motion capture and high-speed video-characterize segmental rotations, sequencing, and variability; kinetic investigations employ force plates and inverse dynamics to quantify ground reaction forces, joint moments, and intersegmental power flows; electromyography and neuromuscular modeling elucidate muscle activation patterns, timing strategies, and coordination that underpin force production and stabilization. Integrating these approaches permits a mechanistic understanding of how technique variations influence both performance metrics (e.g., clubhead speed, launch conditions) and tissue loading that bears on injury risk.

The review aims to translate biomechanical insights into evidence-based recommendations for golfers, coaches, and clinicians: identifying technical determinants of efficient energy transfer, highlighting movement patterns associated with elevated injury risk, and outlining assessment and intervention strategies grounded in objective measurement. The article concludes by proposing priorities for future research-particularly longitudinal, ecologically valid studies and individualized modeling-to advance technique refinement while minimizing injury burden.

Segmental Kinematics and Sequencing: Evidence Based Strategies to Optimize Clubhead velocity and Accuracy

Segmental sequencing follows a robust proximal-to-distal pattern: pelvis initiates the downswing, followed by thoracic rotation, shoulder/arm acceleration, and terminal wrist release. Empirical kinematic studies using motion capture and inertial sensors consistently show that optimal clubhead velocity arises when peak angular velocities occur in this ordered cascade rather than concurrently. Disruption to this timing-early arm acceleration or delayed hip rotation-reduces mechanical advantage and increases inter-trial variability, undermining both distance and reproducibility.

From a kinetic perspective,ground reaction forces and intersegmental torque transfer are critical mediators of kinematic sequencing.Controlled eccentric-to-concentric transitions at the hips create a proximal torque reservoir that the torso and upper limb segments tap into; the magnitude and timing of that transfer determine how much energy is available at the clubhead. Evidence supports training to preserve hip-shoulder separation (X‑factor) through the downswing and to target the temporal offset between peak hip and peak trunk velocities to maximize stored elastic energy and limit undesired compensatory motions.

- Tempo modulation drills: metronome-based downswing timing to preserve intersegmental delays.

- Proximal initiation cues: lead‑hip drive drills emphasizing early pelvic rotation and weight shift.

- Separation reinforcement: resisted thorax rotation exercises to enhance X‑factor maintenance.

- Terminal release control: wrist lag and lead‑arm retention drills to optimize late acceleration without sacrificing face control.

quantitative timing windows can guide practice and feedback. Representative timing benchmarks (expressed as % of downswing duration) and relative contribution estimates illustrate typical sequencing patterns found in trained golfers:

| Segment | Peak Angular velocity (% downswing) | Relative Contribution to Speed (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Hips | ~20-35% | 25-35% |

| Thorax | ~40-60% | 30-40% |

| Shoulder/Arms & Wrists | ~70-95% | 25-35% |

Precision demands intentional trade‑offs: maximal velocity strategies can amplify error if neuromuscular timing is inconsistent. Therefore, training emphasis should progress from restoring reliable proximal sequencing (reducing intertrial variability) to incremental increases in terminal acceleration while monitoring face‑angle consistency. Objective feedback-high‑speed video, IMUs, and force platforms-combined with progressive overload and motor learning principles (blocked to variable practice, external focus cues) yields the best translational gains in both distance and accuracy.

Kinetic Chain mechanics and Ground Reaction force Utilization: Training Recommendations for Efficient Force Transfer

Segmental sequencing underpins efficient transfer of mechanical energy from the ground to the clubhead: lower extremity drive initiates a coordinated cascade through the pelvis, thorax, shoulder girdle and distal forearm. Optimal transfer requires well-timed intersegmental coupling, minimal residual counter-rotation and preservation of angular velocity gradients (proximal-to-distal increase). kinematic variability should be constrained to functional degrees of freedom so that variability in distal segments compensates for small perturbations in proximal output rather than disrupting the kinetic chain.

Ground reaction force vectors are central to power production and must be optimized in magnitude, direction and timing. Relative contributions of the vertical GRF, anterior-posterior shear and mediolateral stabilization determine resultant impulse and the subsequent rotational moment applied about the lumbar-pelvic complex. Key laboratory metrics to monitor include peak force, rate of force progress (RFD), impulse and center-of-pressure (CoP) trajectory; alignment of peak GRF with the period of maximal pelvic rotation is a hallmark of efficient force transfer.

Training should target both force-generating capacity and intermuscular coordination. Effective interventions include unilateral and bilateral plyometrics to raise RFD, hip-dominant strength work to increase moment production, and rotational power drills to improve torso-upper limb coupling. Recommended exercise modalities and cues include:

- Depth jumps – emphasize rapid ground contact and rebound.

- Single-leg RDLs – promote unilateral force symmetry and hip stiffness.

- Rotational medicine-ball throws – prioritize trunk-hip dissociation and sequential acceleration.

- Pallof press progressions – enhance anti-rotation control during high-force transfer.

Neuromuscular timing can be trained with specific drills that shape intersegmental coordination without excessive strength loading. Tempo-modulated swings, pause-and-explode repetitions, and step-on/step-off entry patterns constrain timing so that the pelvic drive precedes thoracic rotation.Incorporate external feedback – video, auditory metronome or force-plate biofeedback – to reinforce desired sequencing and to reduce compensatory motion that dissipates force vector efficiency.

| Exercise | Primary objective | Coaching cue |

|---|---|---|

| Single-leg countermovement | Unilateral force symmetry | “Drive through forefoot, minimize hip drop” |

| Rotational med-ball slam | Trunk-hip power transfer | “Lead with hips, finish with arms” |

| Plyometric broad jump | Explosive horizontal impulse | “Explode long, land quietly” |

Progression should be criterion-based (force/time targets, symmetry indices) and integrated with on-course skills. Prioritize safety and objective monitoring to ensure adaptations enhance rather than attenuate effective force transfer.

Trunk and pelvic Mechanics: reducing Lumbar Spine Stress Through Rotation Control and Mobility Interventions

Effective management of intersegmental motion between the pelvis and thorax is central to minimizing lumbar spine loading during high-velocity swings. Research-informed models emphasize **trunk-pelvic dissociation**-the controlled counter-rotation between the pelvis and the thoracic cage-to distribute rotational work away from the lumbar vertebrae. Maintaining a neutral lumbar curvature while permitting thoracic rotation reduces combined axial torsion and shear, thereby lowering peak compressive and shear stresses during transition and acceleration phases of the swing.

Mechanically, excessive lumbar rotation and early extension create high moment arms that amplify spinal shear forces and eccentric demand on posterior elements. Kinematic analyses show that when pelvic rotation is constrained or poorly timed relative to thoracic rotation, the lumbar spine assumes a compensatory role, increasing both rotational velocity and loading rate. From a kinetic perspective, proper pelvis-to-thorax sequencing attenuates peak trunk moments and redistributes energy generation to larger, more resilient segments (hips and thorax), reducing cumulative microtrauma risk to the lumbar discs and facet joints.

Intervention priorities should target both mobility deficits and neuromuscular control to alter harmful movement patterns. Key objectives include:

- Restoring adequate hip internal rotation and extension to offload lumbar rotation.

- Improving thoracic rotational range and stiffness control to accept rotational work.

- Training pelvic dissociation and timing via low-load motor control drills.

- Progressive load exposure with emphasis on eccentric control through the downswing.

Practical coaching and rehabilitation tactics blend exercise prescription with on-course technique cues. Use targeted mobility routines (thoracic rotations, hip capsule mobilizations) followed by integrated motor-control progressions (dead-bug with resisted pelvic rotation, half-kneeling chops, banded pelvic rotations). The table below summarizes concise intervention-to-effect relationships often used in clinical and coaching settings:

| Intervention | Immediate Effect | Goal |

|---|---|---|

| Thoracic rotation drills | ↑ Thoracic ROM | Shift rotation cranially |

| Hip IR mobilization | ↑ Hip ROM | Reduce lumbar compensation |

| Pelvic dissociation drills | Improved timing | Optimize sequence |

Objective screening and monitoring guide progression and safe return to play. Quantitative criteria-such as side-to-side hip internal rotation symmetry (>30° target), thoracic rotation >45°, and preserved lumbar flexion/extension neutrality under load-provide practical thresholds. Combine these with movement-quality assessments (pelvis-to-thorax lag, early extension index) and workload management (reduced swing volume during reconditioning).Emphasize measurable improvements in both range and timing before reintroducing high-intensity swing repetitions to meaningfully reduce lumbar spine stress.

Shoulder and Scapular Function: Neuromuscular Activation Patterns and Rehabilitation Guidelines to Prevent Overuse injuries

The complex interplay between glenohumeral mobility and scapulothoracic stability is central to producing repeatable, high-velocity golf swings while minimizing injury risk. The shoulder functions as a mobile link in the kinematic chain, requiring coordinated motion across four articulations and dynamic muscular support to translate trunk and lower-extremity torque into distal clubhead velocity. Optimal performance depends on precise scapular positioning throughout the swing to preserve subacromial space, maintain rotator cuff length‑tension relationships, and allow efficient force transfer from the torso to the upper limb.

Electromyographic and kinematic investigations indicate a reproducible neuromuscular sequence during the swing: preparatory activation of scapular stabilizers and posterior cuff muscles during backswing,timed phasic bursts of serratus anterior and lower trapezius during late downswing,and eccentric control of the rotator cuff at impact and follow‑through. This proximal-to-distal activation pattern reduces peak joint loading and organizes momentum transfer. Clinicians should therefore consider not onyl isolated strength but also the timing and amplitude of muscle activation when evaluating shoulder function in golfers.

Repeated high‑velocity rotations and asymmetrical loading predispose golfers to a characteristic spectrum of overuse problems,including subacromial impingement,rotator cuff tendinopathy,and scapular dyskinesis. Contributing neuromuscular deficits commonly include relative weakness or delayed activation of the serratus anterior and lower trapezius, dominant upper trapezius hyperactivity, and imbalance between scapular protractors and retractors. These dysfunctions alter scapulohumeral rhythm, elevate joint contact forces, and increase tensile demand on the anterior capsule and biceps tendon during deceleration phases.

Rehabilitation should be staged and evidence‑driven,emphasizing motor control,progressive loading,and task specificity. Core components include:

- Neuromuscular re‑education-biofeedback and low‑load rhythmic stabilization to restore timing of serratus anterior and lower trapezius;

- Progressive strengthening-closed‑chain and open‑chain exercises targeting rotator cuff endurance and scapular depressor/retractor strength;

- Eccentric control-deceleration drills and plyometric progressions to condition posterior shoulder tissues;

- Versatility and thoracic mobility-posterior cuff, pectoralis minor, and thoracic extension work to normalize scapular kinematics;

- Load management and swing modification-volume control and technical cues to reduce harmful repetitions during early recovery.

These interventions should be monitored with objective measures of strength,scapular motion,and functional tolerance to iterative loading.

Return‑to‑play criteria and preventative maintenance should be explicit and measurable: absence of provocative pain with sport‑specific swings, symmetrical scapular kinematics under load, and restoration of cuff endurance ratios. The table below provides a concise staging framework for clinicians and coaches to coordinate rehabilitation with on‑course demands.

| Stage | Primary Focus | Representative Exercises |

|---|---|---|

| Acute/Protection | Reduce pain, restore motor timing | Scapular rhythmic stabilization, rotator cuff isometrics |

| Strengthening | Build endurance & scapular balance | Prone row, serratus punches, banded external rotation |

| return‑to‑Swing | Power, deceleration control, load tolerance | Medicine‑ball throws, progressive swing‑speed drills |

Ongoing prevention should combine technique refinement, eccentric posterior chain conditioning, and periodic neuromuscular screening to detect early scapular or cuff dysfunction before symptoms progress.

Wrist and Elbow Dynamics: Managing Impulse and Torque to Minimize Injury Risk and Improve Release Timing

The distal upper‑limb acts as the terminal link of a multi‑segment kinetic chain where small temporal perturbations produce large changes in clubhead speed and internal loading. During the downswing and release phase, the combination of angular velocity and lever length generates considerable **wrist and elbow torque**, while the temporal integral of force-mechanical **impulse**-determines net joint impulse exposure. Biomechanically, excessive peak torque with rapid onset (high impulse rate) concentrates stresses on the lateral elbow (radiocapitellar complex) and the wrist extensors and flexor tendons, increasing the risk of tendinopathy and articular irritation documented in clinical series on wrist and elbow pain.

Optimizing release timing requires precise intersegmental sequencing: proximal segments (hips, trunk, shoulder) should decelerate in a controlled manner to permit a progressive transfer of angular momentum to the forearm and club. Effective golfers modulate wrist dorsiflexion and ulnar deviation to shape the release window so that **peak torque** aligns with maximal clubhead velocity rather than being dissipated into the musculoskeletal tissues. From a clinical perspective, smoothing the rise of impulse-through graded deceleration and eccentric control-reduces acute overload and the cumulative microtrauma implicated in overuse syndromes.

Training interventions should therefore target both neuromuscular control and tissue resilience. Key emphases include:

- Controlled eccentric strengthening of wrist extensors/flexors and forearm pronator/supinator groups to absorb impulse.

- Segmental timing drills that reinforce proximal‑to‑distal energy transfer and delay terminal wrist release until optimal kinematic sequencing is achieved.

- Proprioceptive and rate‑of‑force development exercises using light implements to habituate graded torque application.

- Load management protocols that monitor swing counts and progressive intensity to prevent cumulative tendon overload.

| Variable | Modifiable Parameter | Target Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| Peak wrist torque | Release smoothing | Reduced tendon strain |

| Elbow compressive load | Proximal deceleration timing | Lower epicondylar stress |

| Impulse rate | Eccentric control | Decreased acute overload |

Implementation requires objective monitoring and staged progression.Simple clinical measures (pain localization, resisted wrist extension tolerance) and technology (inertial sensors to quantify angular acceleration and torque surrogates) permit early identification of unsafe impulse patterns.rehabilitation and technique modification should prioritize symptom‑guided return, progressive tolerance to torque, and preservation of functional range of motion. Such an integrated approach aligns performance goals with injury mitigation, translating biomechanical insights into durable, evidence‑informed practice.

Neuromuscular Coordination and Motor Learning: Drills and Feedback Protocols to Enhance Timing and Consistency

Effective enhancement of timing and reproducibility in the golf swing requires intentional refinement of intersegmental sequencing and sensorimotor integration. Contemporary biomechanical analyses emphasize a **proximal-to-distal activation pattern**, anticipatory postural adjustments and consistent ground reaction force timing as core determinants of repeatable club-head kinematics.Training should therefore target both the temporal coordination of large muscle synergies (hips, trunk, shoulders) and the precise scaling of distal musculature (forearms, wrists) to reduce variability across swings.

Practice tasks that isolate and reinforce critical temporal events accelerate motor adaptation. Recommended drills include:

- Metronome rhythm drill – synchronize downswing onset to a set beat to stabilize tempo and transition timing;

- Pelvis-first rotation – restricted-arm swings emphasizing lead-side rotation to restore proximal initiation;

- Pause-at-top – brief static hold at transition to improve timing of weight shift and sequence onset;

- Impact-sensation – light impact bag or reactive surface to refine deceleration and compressive timing at impact.

Each drill should be prescribed with explicit success criteria and scaled from slow to sport-speed once coordination becomes consistent.

Feedback design should follow motor learning principles that maximize retention and transfer. Emphasize an **external focus** of attention (e.g., ball flight, target line) over internal mechanics when possible, and employ augmented feedback schedules such as faded and bandwidth feedback to prevent dependency. Multimodal feedback-low-latency video for kinematic replay, auditory cues for tempo, and wearable haptics for onset timing-can be combined, but reduced frequency and summary feedback are recommended as proficiency develops to promote autonomous error detection and correction.

| Drill | Primary Target | Preferred Feedback |

|---|---|---|

| Metronome rhythm | Tempo & transition | Auditory beat |

| Pelvis-first rotation | Proximal initiation | Video + coach cue |

| Pause-at-top | Sequencing & timing | Summary verbal |

| Impact-sensation | Deceleration timing | Haptic/reactive |

Program progression must balance specificity, variability and workload control to consolidate motor learning while minimizing injury risk. Begin with high-repetition, low-load blocked practice to ingrain temporal patterns, then introduce variable and randomized contexts to enhance adaptability and transfer to on-course conditions. Use retention and transfer tests at planned intervals; consider a progression criterion such as 80-90% consistency in key timing metrics before increasing speed or adding fatigue.Monitor neuromuscular signs of overload (excessive soreness,altered swing kinetics) and adjust volume or feedback density accordingly to protect tissue and preserve motor quality.

Fatigue Effects and Load Management: Periodization Principles and Conditioning to Maintain Biomechanical integrity

Acute and cumulative fatigue produce measurable degradation in the neuromuscular substrates that underpin an efficient golf swing; **reduced force capacity, altered motor unit recruitment, and impaired proprioception** all manifest as deviations from optimal kinematics.Clinical sources emphasize that persistent fatigue is frequently enough multifactorial-ranging from lifestyle contributors such as sleep deficit and inadequate recovery to medical conditions that produce chronic malaise-thereby necessitating differential diagnosis when performance decrement persists despite structured intervention.

Biomechanically, fatigue precipitates characteristic alterations: reduced peak rotational velocities, increased lateral sway at the pelvis, diminished sequencing between lower- and upper-body segments, and compensatory increases in shoulder and wrist muscular activity. These changes elevate joint loading in compensation patterns, amplify shear and torsional moments at the lumbar spine, and increase the propensity for overuse pathology. **Maintaining kinetic sequencing integrity across the ground-up kinetic chain is therefore a primary objective of fatigue management.**

Effective load management integrates periodization principles with athlete-specific conditioning and monitoring. Core strategies include:

- Macro-to-micro structuring – define annual goals and distribute intensity/volume across mesocycles

- Planned deloads – scheduled reductions in volume and intensity to restore neuromuscular homeostasis

- Autoregulatory adjustments – real-time scaling of sessions using readiness metrics

- Cross-modal conditioning – blend mobility, strength, power, and low-impact aerobic work to reduce repetitive tissue stress

Translating periodization into practice requires targeted conditioning modalities that preserve biomechanical integrity: eccentric-loaded hip and trunk programs to control energy transfer, rotational power work to restore sequencing, and neuromuscular control drills to retain position sense under fatigue. The table below provides a concise template linking phase, primary objective, and typical duration for a mid-season maintenance program.

| Phase | Primary Objective | Typical Duration |

|---|---|---|

| Preparatory | Build strength/endurance | 6-8 weeks |

| Competitive | Maintain power, minimize fatigue | 4-6 weeks |

| Deload/Recovery | Neuromuscular restoration | 7-14 days |

Surveillance and clinical awareness are indispensable: deploy objective readiness metrics (e.g., jump power, sprint times, HRV trends) and subjective scales (RPE, sleep quality) to guide progression. **Refer athletes for medical evaluation when fatigue is disproportionate to load**-noting that some syndromes associated with chronic fatigue (for example, post-viral sequelae) require interdisciplinary management and that constructs like “adrenal fatigue” are not established diagnostic entities. Integrating physiological monitoring, structured periodization, and targeted conditioning preserves swing mechanics while minimizing injury risk.

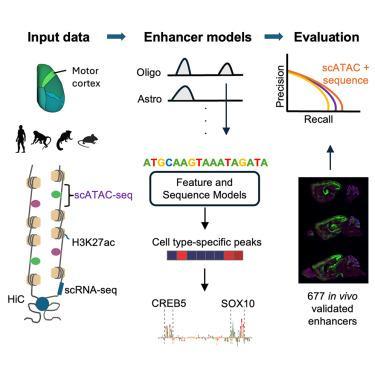

Measurement Techniques and clinical assessment: Integrating Motion Capture Force Platforms and EMG for Individualized Technique Refinement

Contemporary clinical assessment of the golf swing employs a triad of biomechanical measurement modalities to capture kinematic, kinetic and neuromuscular dimensions concurrently. When integrated, **motion capture**, **force platform** and **electromyography (EMG)** provide complementary evidence: segmental kinematics describe movement patterns, ground reaction forces quantify external load transfer, and EMG reveals the timing and magnitude of muscular drive.Together these data form an objective substrate for individualized technique refinement, enabling clinicians and coaches to move beyond subjective observation toward targeted, measurable interventions that reduce injury risk and optimize performance.

Methodological rigor in motion capture is essential to preserve validity and reliability. Use of **marker-based** or contemporary **markerless** systems should be decided on the basis of task fidelity, lab resources and required outcome precision. Critical considerations include camera count, calibration volume, sampling rate and biomechanical model choice; poor calibration or low sampling frequency compromises joint center estimation and temporal alignment with force and EMG streams. Best-practice recommendations include:

- Sampling rate: ≥200 Hz for marker-based 3D kinematics; ≥500 Hz for high-speed club-head or impact frame capture.

- Camera count & calibration: ≥8 cameras for full-body models in swing planes with a validated static-dynamic calibration protocol.

- Modeling: use a multi-segment trunk/pelvis model and report marker sets and marker-placement reliability.

Ensuring **synchronization** across systems-hardware trigger or shared clock-is non-negotiable for temporal analyses such as onset latencies and sequencing indices.

Force-platform assessment quantifies the kinetic interface between player and ground and is indispensable for evaluating weight transfer, lateral force production and off-plane loading that predisposes to overuse. Dual-plate force platforms enable inter-limb comparisons and center-of-pressure (COP) trajectory analysis; single-platform setups can still yield useful bilateral-phase data with careful foot placement protocols. Key kinetic metrics include **peak vertical and medio-lateral GRF**, **vertical impulse**, **rate of force development (RFD)** and COP excursion and velocity. Clinicians should apply low-pass filtering consistent with kinematic processing, document platform sampling rates (typically ≥1000 Hz for impact events), and compute asymmetry indices to screen for compensatory strategies or injury-related unloading.

Surface EMG provides direct insight into neuromuscular timing, recruitment amplitude and inter-muscular coordination that underlie effective swing mechanics. Electrode placement must follow SENIAM or equivalent guidelines, with skin planning to reduce impedance and standardized inter-electrode spacing. EMG processing should include **band-pass filtering** (typical 20-450 Hz), full-wave rectification and appropriate smoothing or linear envelope generation; normalization to **maximum voluntary contraction (MVC)** or functional submaximal tasks is required for between-subject comparisons. Muscles of primary interest commonly include the bilateral gluteus maximus/medius, erector spinae (thoracic and lumbar), external obliques, rectus abdominis and pectoralis major; monitoring these allows assessment of sequencing, co-contraction and fatigue.Typical EMG-derived outcomes used clinically are: onset latency relative to address, peak activation magnitude (%MVC), and duration of elevated activity-metrics that inform both technique adjustments and conditioning prescriptions.

Translating integrated data into individualized technique refinement demands a structured clinical workflow: (1) standardized data collection with documented reliability, (2) normative or intra-subject baseline comparison, (3) identification of mechanically unsafe or inefficient patterns, and (4) targeted intervention with measurable goals and re-assessment. Use of **objective thresholds** (e.g., COP medial excursion, inter-limb GRF asymmetry >10%, delayed gluteal onset >30 ms relative to pelvic rotation) facilitates decision-making and progression criteria. The table below presents exemplar metrics and practical target ranges to guide interpretation and goal-setting in an amateur male cohort; adapt thresholds to athlete level and clinical context and report the minimal detectable change (MDC) when available. Augment biomechanical prescriptions with multimodal feedback (visual kinematic overlays, real-time force or EMG biofeedback and progressive strength/power interventions) and schedule re-evaluation to confirm transfer to on-course performance and to monitor injury-risk reduction.

| Metric | Typical Range (male amateur) | Clinically Meaningful Change |

|---|---|---|

| Peak vertical GRF (N·kg⁻¹) | 1.8-2.6 | ±0.2 |

| COP lateral excursion (cm) | 6-12 | ±1.5 |

| Pelvis-thorax X-factor (°) | 20-45 | ±3 |

| Gluteus medius onset (ms) | −10 to +40 (relative) | ±15 |

Q&A

Note on search results

– The provided web search results did not contain material relevant to “Biomechanical Analysis of the Golf Swing Technique.” the Q&A below is produced on the basis of current biomechanical principles, peer-reviewed literature trends (kinematics, kinetics, neuromuscular dynamics), and applied coaching/rehabilitation practice, rather than the supplied links.

Q&A – Biomechanical Analysis of the Golf Swing Technique

1) Q: What is meant by “biomechanical analysis” of the golf swing?

A: Biomechanical analysis is the quantitative study of the motion (kinematics),the forces and moments that cause motion (kinetics),and the neuromuscular control (muscle activation,timing) underlying the golf swing. It aims to describe movement patterns, identify performance determinants (e.g., clubhead speed, accuracy), and explain mechanisms that contribute to injury or suboptimal technique.

2) Q: Which kinematic variables are most informative for evaluating swing technique?

A: key kinematic variables include: clubhead speed and path; pelvis and thorax rotation and rotation velocities; X‑factor (torso-pelvis separation angle) and X‑factor stretch; lead and trail arm angles; wrist hinge and release timing; spine tilt and inclination; swing plane; and temporal sequencing (onset and peak angular velocities). Inter-joint sequencing (proximal-to-distal timing) is particularly informative for efficient energy transfer.

3) Q: What kinetic measures matter for performance and injury risk?

A: Critically important kinetic measures include ground reaction forces (peak vertical, mediolateral, anterior-posterior components), joint moments and powers (lumbar, hip, shoulder, elbow, wrist), net joint forces (compressive and shear), and intersegmental power transfer. High torsional moments and repeated high compressive/shear loads at the lumbar spine are linked to injury risk.

4) Q: How do neuromuscular dynamics contribute to swing quality?

A: Neuromuscular dynamics encompass activation timing, magnitude, co-contraction strategies, feedforward preparatory activity, and the use of stretch-shortening cycles. Effective swings show coordinated pre-activation of trunk rotators and timely activation of hip extensors and shoulder muscles to produce efficient proximal-to-distal sequencing and stabilize joints against large loads.5) Q: What measurement tools and sample rates are recommended?

A: Common tools: 3D optical motion capture (marker-based or markerless), high-speed video (≥200 fps for club and wrist detail), force plates (dual/portable; ≥1000 Hz for impact/force transients), electromyography (EMG; 1000-2000 Hz), inertial measurement units (IMUs), and plantar pressure mats. Sampling rates depend on the signal: kinematics often ≥200 Hz for club dynamics; kinetics and EMG require higher sampling to resolve transient peaks.

6) Q: What modelling methods are used to derive kinetics?

A: Inverse dynamics is standard: combine kinematic data and external forces (force plate) to compute joint moments/powers. Musculoskeletal modelling (OpenSim, AnyBody, custom models) can estimate muscle forces and joint contact forces, but requires careful anthropometric scaling and validation.7) Q: What are common biomechanical differences between elite and recreational golfers?

A: Elite players typically exhibit greater clubhead speed, larger and well-timed X‑factor or X‑factor stretch, higher peak rotational velocities of pelvis and thorax, more consistent proximal-to-distal sequencing, and more efficient ground force application. Recreational players often show inefficient sequencing, premature arm-dominated swings, reduced pelvic rotation, and inconsistent weight transfer.

8) Q: What is the “X‑factor” and why does it matter?

A: X‑factor is the rotational separation between the pelvis and thorax at the top of the backswing (torso rotation angle minus pelvis rotation angle). Larger X‑factor or controlled X‑factor stretch (increase during early downswing) can increase elastic energy stored in trunk soft tissues and enhance clubhead speed, but excessive or uncontrolled X‑factor can raise lumbar torsional loads and injury risk.

9) Q: What movement patterns are commonly associated with higher injury risk?

A: Repetitive high torsional moments and shear/compressive loads at the lumbar spine (lumbar hyperrotation, lateral bending during rotation), abrupt deceleration/impact patterns at the wrist/forearm, excessive shoulder elevation/anterior translation, and valgus/varus elbow loading patterns. Faulty sequencing (late or abrupt deceleration of proximal segments) can increase joint loads.

10) Q: Which anatomical sites are most vulnerable in golfers?

A: The lumbar spine (disc and facet joint loading), shoulder (rotator cuff and labrum), elbow (medial and lateral structures; e.g., ulnar collateral stress and lateral epicondylopathy), wrist (extensor tendinopathies, TFCC), and hip/groin region (adductor/hip flexor strains) are commonly affected.

11) Q: How can biomechanical analysis inform technique refinement for performance?

A: It identifies inefficient kinematic patterns (e.g.,early cast,over‑rotation,poor weight shift) and quantifies kinetic deficits (insufficient ground force application,poor power transfer). Interventions target improved sequencing (initiate downswing with pelvic rotation), optimized X‑factor stretch, consistent swing plane, maintained spine angle, and efficient wrist hinge/release-all backed by measurable pre-post comparisons.

12) Q: What evidence‑based training and conditioning strategies reduce injury risk and improve performance?

A: Multimodal programs: mobility work (thoracic rotation,hip internal/external rotation),strength (hip extensors,gluteal complex,trunk rotators,rotator cuff),power and plyometric training (rotational medicine ball throws,hip-rotation drills),eccentric control (to decelerate segments),neuromuscular control and balance exercises,and progressive load management. Emphasize motor learning principles (progressive variability,augmented feedback,deliberate practice).

13) Q: What coaching cues or drills are supported by biomechanical rationale?

A: Examples: “Lead with the hips” (promotes pelvic initiation and proximal-to-distal sequencing), “Maintain yoru spine angle” (reduces excessive lateral bend and shear), “Hold the wrist hinge” (promotes late release and increases clubhead speed), weight-transfer drills (step-through drills, split-stance practice), and rotational medicine ball throws to train timing and power transfer.Use objective feedback (video, force plate/IMU metrics) for better translation.

14) Q: How should objective data be presented to coaches and players?

A: Use concise, interpretable metrics (clubhead speed, peak pelvis/thorax angular velocities, X‑factor and X‑factor stretch, timing of peak velocities, ground reaction force profiles). provide normative or baseline comparisons (team/peer or player history) and actionable prescriptions (specific mobility, strength, or technique drills). Visualizations (time-series of segmental angular velocity and force curves) are helpful if explained.

15) Q: What measurement limitations and sources of error must be considered?

A: Skin motion artifact in marker-based capture, marker placement variability, errors in joint center estimation, inverse dynamics assumptions (rigid segments), limited ecological validity in lab settings (e.g.,hitting into nets vs. course play), and EMG cross-talk. Wearable devices and markerless systems improve ecological validity but have their own accuracy trade-offs; validation against gold-standard systems is necessary.

16) Q: How can analysis be tailored to different populations (e.g., juniors, seniors, women, injured players)?

A: Account for anthropometry, strength/mobility capacity, injury history, and motor development. For juniors emphasize motor skill acquisition and progressive loading; for seniors focus on mobility,strength preservation,and reduced high-magnitude torsional loads; for women,consider differences in strength distribution and segmental coordination. Individualized normative ranges and phased progressions are essential.

17) Q: What role does variability and motor learning theory play in technique change?

A: Introducing controlled variability during practice can enhance robustness and transfer; contextual interference and goal-directed practice improve retention. Overly prescriptive repetition may limit adaptability. Use augmented feedback (knowledge of results and performance) judiciously and progressively reduce external feedback to promote self-regulation.

18) Q: What are realistic performance targets or normative ranges?

A: Targets depend on skill level, sex, age, and equipment. Instead of fixed universal numbers, use relative improvements (e.g., measurable increases in peak pelvis/thorax angular velocity, improved sequencing timing, or % increase in delivered clubhead speed) and player-specific baselines. When absolute ranges are required, consult peer‑reviewed normative datasets matched for population.

19) Q: How can biomechanical analysis support rehabilitation and return-to-play decisions?

A: Objective metrics (joint moments, muscle activation symmetry, force generation capacity, and movement patterns) can track progress, identify residual deficits, and inform criteria-based return-to-play (e.g., restoration of symmetrical ground force profiles, normalized rotational velocities, adequate dynamic trunk control). Combine biomechanical assessment with clinical examination and pain/function scales.

20) Q: What are priority areas for future research and applied development?

A: Improving ecological validity (on-course measurement), validating and standardizing wearable/markerless systems, integrating multi-sensor real-time biofeedback, individualized musculoskeletal models for better joint-contact force estimates, longitudinal studies linking biomechanical metrics to injury incidence, and machine learning approaches to classify technique faults and prescribe interventions.

21) Q: How should researchers and practitioners report biomechanical analyses to be most useful?

A: Report clear participant characteristics (skill level, sex, age), measurement systems and sampling rates, marker or sensor protocols, filtering and processing parameters, model assumptions, and both kinematic and kinetic outcomes with temporal references (e.g., time to peak velocity relative to ball impact). Provide effect sizes and confidence intervals for observed changes and, when possible, practical recommendations.

22) Q: What practical workflow do I use to conduct an evidence-based biomechanical assessment?

A: Recommended workflow: (1) Define questions/metrics of interest (performance vs. injury), (2) baseline screening (mobility, strength, injury history), (3) capture kinematics/kinetics/EMG under representative conditions, (4) process data with validated pipelines, (5) interpret against baselines/norms and movement models, (6) prescribe targeted interventions (technique drills + conditioning), (7) re-assess with objective metrics and patient/player‑reported outcomes, (8) iterate.

Summary practical takeaways (brief)

– Focus on efficient proximal-to-distal sequencing, appropriate X‑factor with controlled stretch, preserved spine angle, and effective ground force application to optimize clubhead speed and accuracy.

– Reduce injury risk via mobility (thoracic, hip), strength (gluteal, trunk rotators), eccentric control, and motor control training.

– Use objective measurement (motion capture/IMU, force plates, EMG) where feasible, and translate data into concise, actionable coaching cues and targeted conditioning programs.

– Recognize individual variation and validate interventions with pre/post objective testing.If you would like, I can:

– Convert this Q&A to a formatted appendix for an academic article,

– Provide a one-page assessment protocol (equipment, marker set, sample rates, processing steps),

– Or draft evidence‑based drills and a 6-12 week conditioning program tailored to a specific population (e.g.,recreational male,junior,senior).

To Conclude

a biomechanical perspective that integrates kinematics, kinetics and neuromuscular dynamics provides a coherent framework for understanding both the determinants of effective ball-striking and the mechanical contributors to injury in the golf swing. Consistent evidence supports a proximal‑to‑distal sequencing model,efficient transfer of angular momentum through coordinated segmental coupling,and the generation and timing of ground reaction forces and torso‑pelvis separation as central to producing clubhead speed while moderating joint loading. Neuromuscular control-timing, amplitude and intersegmental variability-emerges as the mediator that links mechanical capacity to repeatable performance.

for practitioners, these insights translate into concrete, evidence‑based priorities: (1) emphasize motor patterns that preserve proximal‑to‑distal sequencing and reduce deleterious compensations; (2) incorporate strength, mobility and sensorimotor training targeted to the lumbopelvic complex, hips and scapulothoracic region; (3) adopt progressive load‑management and fatigue‑monitoring strategies to limit cumulative spinal and upper‑extremity stress; and (4) use objective assessment (motion analysis, force measurement, wearable inertial sensors and EMG where feasible) to individualize technique adjustments and conditioning prescriptions.

Clinicians and coaches should balance high‑resolution biomechanical testing with pragmatic, field‑ready tools and cues that promote durable motor adaptation.Technical interventions are most effective when paired with capacity building (e.g., hip rotational strength, thoracic mobility, eccentric control) and when informed by reliable metrics of asymmetry, timing and external loading. Injury prevention is best achieved through an integrated approach combining technique refinement, physical preparation, and gradual exposure to competitive loading.

Future research should prioritize longitudinal, ecologically valid intervention trials, greater inclusion of female and older golfer populations, and translational studies that connect laboratory measures to on‑course outcomes. Advances in wearable sensors, machine learning and real‑time feedback create opportunities to scale biomechanical assessment and personalized coaching, but these tools require rigorous validation. By continuing to bridge biomechanical science and applied practice, coaches, clinicians and researchers can better optimize performance while reducing injury risk-advancing the practice of golf in a manner that is both effective and sustainable.

Biomechanical Analysis of the Golf Swing Technique

Understanding the golf Swing as a Biomechanical System

The golf swing is a complex, multi-joint movement that blends strength, coordination, timing, and technique. An evidence-based biomechanical analysis breaks the swing into measurable components-grip mechanics, stance and posture, kinematic sequencing, weight transfer, and clubhead dynamics-to improve ball striking, consistency, and distance. This article explains the science behind a powerful, repeatable golf swing and provides practical tips and drills to apply biomechanical principles on the range and course.

Key Biomechanical Concepts and Golf Keywords

- Kinematic sequence: Order and timing of segmental rotations (hips → torso → arms → club) that maximize clubhead speed.

- Ground reaction forces (GRF): Forces from the ground that drive rotation and weight shift.

- X‑Factor: Separation between hip and shoulder rotation at the top of the backswing that increases stored elastic energy.

- Clubhead speed & launch conditions: Variables including speed, path, face angle, launch angle, and spin rate that determine carry and dispersion.

- Center of pressure: How weight moves across the feet during the swing influencing balance and power.

Grip Mechanics and Clubface Control

Grip is the only contact between the player and the club-small changes affect face control, club path, and shot shape. Biomechanically, the grip affects wrist mechanics, forearm rotation, and the club’s release through impact.

Biomechanical grip checklist

- Neutral grip: thumbs centered along the shaft to promote square face at impact.

- pressure distribution: moderate grip pressure (3-5/10) reduces tension and allows wrist hinge and release.

- Wrist alignment: slight ulnar deviation in address aids set up of clubface for consistent release.

Posture, Stance, and Alignment

Optimal posture sets the foundation for consistent swing plane and efficient power transfer. Key posture metrics include spinal tilt, knee flex, hip hinge, and head stability.

- spine angle: maintain a stable torso tilt (neutral spine) to allow rotation without excessive lateral movement.

- Shoulder alignment: shoulders square (or slightly open) to target for repeatable clubpath.

- Stance width: shoulder- to slightly wider-than-shoulder width depending on club (wider for driver for stability).

Kinematic Sequence: The Engine of the Swing

The ideal kinematic sequence generates maximal clubhead speed while minimizing stress on joints. The typical efficient order is:

- Lower body initiation (pelvic rotation and weight shift)

- Torso/upper body rotation

- Shoulder and arm delivery

- Club release and wrist action through impact

When this sequence is preserved, each proximal segment (closer to the body) accelerates and then transfers energy to the next distal segment, magnifying clubhead speed at impact-this is the essence of the kinematic chain.

Ground Reaction Forces,Weight Transfer & balance

GRF analysis shows golfers generate force into the ground and redirect it into rotational work. Efficient players create a lateral-to-linear transfer: push into the ground with the trail foot during the downswing while shifting weight to the lead foot for solid contact.

- early weight shift: excessive lateral slide reduces rotational torque and timing.

- Dynamic balance: center of pressure moves from trail to lead foot between top and impact.

- Force timing: peak GRF occurs slightly before impact in efficient swings-this helps stabilize the lower body during club release.

Clubhead Path,Face Angle,and ball Flight

The interaction of clubhead path and face angle at impact determines ball starting direction and curvature. Biomechanical measurement tools (launch monitors) provide critical data:

- Club path (in-to-out vs out-to-in)

- Face angle (open, square, closed)

- Face-to-path relationship: primary determinant of shot shape

- Impact location on the face: off-center hits reduce ball speed and increase spin irregularities

Common Biomechanical Faults & Fixes

- Early extension: hips move toward the ball on downswing. Fix: stability drills, strengthen glutes and hip hinge awareness.

- Over-the-top (steep downswing): improper swing plane causing slices. Fix: shallow transition drills, maintain width and proper wrist hinge.

- Lack of sequencing: arms dominate the swing, reducing power. Fix: lead with hips in transition; use step-through or pause drills to train sequence.

- Grip tension: limits wrist hinge and release. Fix: use relaxation and rhythmic tempo drills; practice with light clubs.

Measuring the Swing: Tools & Metrics

Modern coaching integrates motion capture, inertial measurement units (IMUs), force plates, and launch monitors to quantify biomechanics. Important metrics for golfers include:

| Metric | Why it matters | Target / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Clubhead speed | primary predictor of distance | Driver: 95-125+ mph for advanced players |

| Kinematic sequence | Efficient energy transfer | Hips → torso → arms → club |

| X‑Factor | Stored elastic energy | ~20-40° difference (player-dependent) |

| Smash factor | Ball speed / clubhead speed, efficiency | Driver: ~1.45-1.50 |

Training Strategies: Strength, Mobility & Motor Control

Biomechanics informs training-targeted strength and mobility programs improve the physical capacities that underlie technique.

Mobility priorities

- Thoracic rotation for shoulder turn and X‑Factor

- Hip internal/external rotation for pelvis rotation

- Ankle dorsiflexion for stable weight transfer

Strength & power priorities

- Glute and hip strength for stable rotation and force generation

- Rotational core power for efficient torque transfer

- Lower-body explosive strength (plyometrics) to augment GRF

Motor control & drills

- Slow-motion sequencing drills to feel correct kinematic timing

- Impact bag or towel drill to improve release and compress ball

- Rotational medicine-ball throws to train coordinated hip-to-shoulder transfer

Practical Range Drills to Apply Biomechanics

- Hip-lead drill: Pause at the top, start downswing with a conscious hip rotation before the arms.

- Step & drive drill: Step toward the target during transition to train weight shift and timing.

- Slow-to-fast ladder: 3 slow swings → 2 medium → 1 full-speed to groove tempo and sequencing.

- Face control hitting: Half shots focusing on hitting center of face and square face at impact.

Case Studies & Real-world Applications

Biomechanical interventions can be highly individualized. Two common case examples show how analysis changes outcomes:

- Case A – Amateur slice: Motion-capture revealed an out‑to‑in club path with early upper-body rotation. Intervention: plane drills, reduced handcast, and hip rotation drills. Result: straighter ball flight, improved dispersion.

- Case B – Low clubhead speed but solid technique: Analysis showed limited thoracic rotation and weak glute activation. Intervention: mobility and power program (medicine ball rotational throws and hip-hinge strength). Result: increased driver carry through better torque and power transfer.

How to Use Technology Effectively

Don’t let data overwhelm you. Focus on 2-3 metrics that align with your primary issue (e.g., clubhead speed and path for distance and accuracy). Steps to integrate tech:

- Baseline testing with launch monitor and video.

- Target 1-2 measurable variables (e.g., increase X‑Factor or reduce club path deviation).

- Implement drills + strength/mobility program for 6-8 weeks.

- Retest and iterate; use objective measures and feel-based feedback together.

Injury Prevention & Load Management

Biomechanics not only improves performance but reduces injury risk by ensuring movements distribute loads appropriately. Common injury-related issues include excessive spinal extension, forced lateral slide, and repetitive asymmetries.

- Warm-up routines: dynamic mobility focusing on hips and thoracic spine.

- Monitor fatigue: swing changes when tired-reduce practice volume or focus on maintenance.

- Balanced training: address side-to-side strength to reduce asymmetry-related injuries.

SEO Tips For Publishing This Content

- Use the target keyword “biomechanical analysis of the golf swing” in the H1, meta title, and meta description.

- Include related long-tail keywords in subheadings and throughout the body: “golf swing biomechanics,” “clubhead speed,” “kinematic sequence,” ”swing plane,” “launch monitor data.”

- Structure content with H2/H3 tags, short paragraphs, and bullet lists for readability (good for featured snippets).

- Include a table of swift metrics (as above) for scannability and potential rich results.

- Use internal links on your site to related pages (e.g., drills, lesson booking, equipment guides) and authoritative outbound sources when necessary.

Practical Checklist Before Your Next Practice Session

- Record a short video of your swing (down-the-line and face-on).

- Warm up with mobility drills (5-10 minutes).

- Pick one biomechanical focus (e.g., weight transfer) and 2 drills to reinforce it.

- Use a launch monitor or measurable target to track improvements.

- Rotate strength and mobility work into your weekly plan to support technique.

Implementing biomechanical principles-measured through video, IMUs, force plates, and launch monitors-creates a direct pathway to more consistent ball striking, higher clubhead speed, and better shot control. Use the drills, training priorities, and measurement checklist above to build an efficient, repeatable golf swing rooted in biomechanics.