Note: the provided web search results do not appear to be related to golf equipment or the topic requested. Proceeding to draft the requested academic introduction.

Introduction

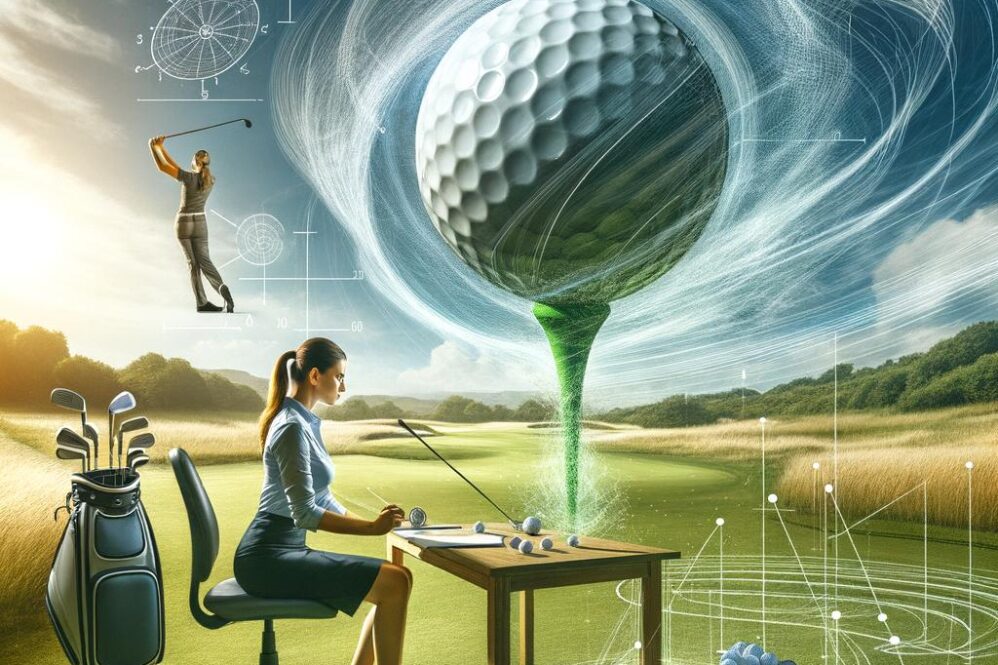

Advances in golf performance are increasingly driven by the interaction of equipment design and human biomechanics. Clubhead geometry, shaft dynamics, and grip ergonomics each modulate the transfer of mechanical energy from player to ball, and their coupled effects determine key outcome variables such as ball launch conditions (speed, launch angle, spin) and shot dispersion. Historically, manufacturers and researchers have examined these components in isolation-optimizing aerodynamics of head shapes, tailoring shaft stiffness and torque to swing tempo, or evaluating grip form for comfort and control-but relatively few studies have integrated biomechanical modeling with aerodynamic testing to quantify how equipment parameters interact with the player’s kinematics to influence on-course outcomes.

This study presents a combined biomechanical and aerodynamic evaluation of golf equipment aimed at elucidating the multiscale mechanisms by which geometry, dynamics, and ergonomics affect swing efficiency and ball flight variability.We employ motion-capture and multibody-dynamics modelling to characterize player-club interaction and energy transfer, coupled with computational fluid dynamics and wind-tunnel experimentation to resolve the aerodynamic forces and moments acting on the clubhead and ball during critical phases of the swing. Attention is given to metrics that bridge biomechanics and aerodynamics-effective face velocity, impact angle, clubhead stability (rotational inertia and damping), and post-impact ball spin and launch vector-while also considering how grip compliance and hand placement alter kinematic chains and shot repeatability.

By integrating experimental data and numerical simulation, the investigation seeks to (1) quantify the sensitivity of launch and dispersion outcomes to variations in clubhead geometry, shaft dynamic properties, and grip ergonomics; (2) identify interaction effects that are not apparent when components are evaluated separately; and (3) derive evidence-based recommendations for equipment design and personalized fitting strategies. The results aim to inform manufacturers, fitters, and clinicians about trade-offs between performance, consistency, and injury risk, and to provide a methodological framework for future multidisciplinary studies of sport equipment.

Kinematic Modeling of the Golf Swing and Its Implications for Clubhead Speed

Kinematic analysis treats the golfer-club system as a linked multi‑segment model in which the torso, pelvis, arms, wrists, and club are represented as rigid bodies connected by articulated joints. High‑fidelity capture (marker‑based optical systems, IMUs) provides segmental orientations and joint angles, which are processed via inverse kinematics to reconstruct joint centers and angular velocities throughout the swing. Emphasis is placed on temporal sequencing and the establishment of local coordinate frames for each segment so that intersegmental transfer of angular momentum can be quantified with minimal error; **segmental sequencing** and accurate joint axis definition are prerequisites for reliable estimates of clubhead velocity at impact.

The mechanistic link between body kinematics and clubhead speed is mediated by a small set of measurable variables that consistently explain variance in peak head velocity. Primary kinematic predictors include:

- Peak angular velocities of the hips, torso, and lead arm (measured in rad·s⁻¹)

- Timing offsets between segmental peaks (intersegmental phase relationships)

- Wrist **** and uncocking rate (hand release kinematics)

- Club shaft angular velocity and bending dynamics near impact

These variables interact nonlinearly; for example, modest increases in torso angular velocity can disproportionately increase clubhead speed when coupled with optimized wrist release timing.

Modeling frameworks range from simplified planar kinematic chains to full three‑dimensional multibody dynamics. Practical implementations often incorporate kinematic coupling strategies to reduce degrees of freedom where experimental constraints demand it-analogous to control‑point coupling used in finite‑element environments-to enforce consistent relationships between grip contact points and the proximal shaft node. Inverse dynamics then translates measured kinematics into net joint moments and power flows, enabling separation of active muscular contribution versus passive mechanical transfer. These approaches allow identification of whether clubhead speed is power‑limited (joint torque deficits) or timing‑limited (suboptimal sequence), which directly informs equipment tuning and training interventions.

| Component | Kinematic Effect | Typical Direction |

|---|---|---|

| Clubhead geometry | Alters effective moment arm and required angular velocity for given linear speed | Increase MOI → requires higher angular input |

| Shaft stiffness & kick point | Modifies shaft bending phase and peak tip velocity timing | Stiffer → earlier peak; flexible → delayed peak |

| Grip interface | Constraints wrist rotation and alters hand‑shaft relative kinematics | Higher friction → reduced slip, more predictable release |

Translational application of kinematic models includes targeted coaching cues, equipment fitting, and virtual prototyping. Recommended measurement practices are: high sampling rates (>200 Hz) for club and wrist kinematics, synchronized force/pressure data at the grip to resolve hand‑shaft coupling, and event‑aligned averaging to assess timing consistency. Key actionable insights-summarized below-bridge analysis to intervention:

- prioritize timing over raw torque increases for many mid‑handicap players.

- Tune shaft dynamics to the golfer’s release timing rather than defaulting to nominal flex labels.

- Use grip ergonomics to stabilize hand‑shaft kinematics and reduce dispersion without necessarily increasing peak speed.

Together, these kinematic considerations provide a rigorous foundation for improving clubhead speed while managing shot dispersion through equipment and technique co‑optimization.

Influence of Clubhead Geometry on Aerodynamic Lift, Drag, and Ball Launch Conditions

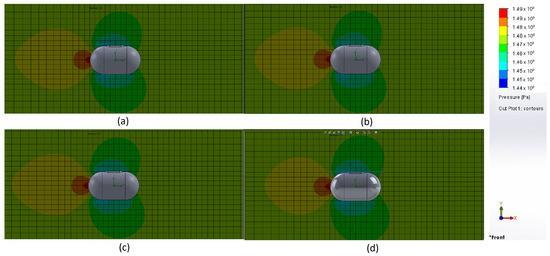

The three-dimensional shape of the clubhead fundamentally alters the pressure field around the club during the brief interaction with the free stream and the golf ball, producing measurable changes in **aerodynamic lift** and **drag**. Frontal area, camber of the crown, trailing-edge geometries and the distribution of surface curvature determine rates of boundary-layer transition, separation and vortex formation; these phenomena change the net aerodynamic force vector acting on the head and, by extension, the initial conditions of the ball at impact. From an engineering outlook, geometry shifts the effective aerodynamic center and modifies the time-dependent flow topology during the downswing and at impact, thereby influencing launch angle, backspin generation, and initial sidespin components that control trajectory and dispersion.

Specific geometric design elements exert distinct aerodynamic roles and interact nonlinearly with ball-face collision mechanics. Key influences include:

- Face curvature and loft geometry – modulate contact patch evolution and spin loft, affecting backspin magnitude and vertical launch.

- Crown/tapering and trailing-edge shaping – influence wake structure and drag coefficient under varying yaw and attack angles.

- Toe-heel mass distribution and skirt geometry – change crossflow separation behavior and sensitivity to off-centre impacts (gear effect), altering sidespin and shot bias (e.g., draw tendencies).

These design elements do not act independently; their aerodynamic influence is conditioned by impact location, loft, and instantaneous angle of attack.

| Geometric feature | Aerodynamic Effect | Typical Launch Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| Rounded crown / slim trailing edge | Reduced separated wake | Slightly lower drag → modestly increased carry |

| High face bulge | Consistent contact orientation | Stabilized sidespin → reduced dispersion |

| Expanded skirt / low-profile sole | Altered pressure distribution | Higher launch with increased backspin |

Integration with player biomechanics amplifies or attenuates aerodynamic effects. Swing speed, shaft flex dynamics and attack angle determine the relative velocity and orientation of the head at impact, which in turn changes Reynolds number and effective yaw; faster swings increase Reynolds-dependent lift and drag magnitudes, while variable shaft deflection can induce micro-rotations of face angle at impact that produce pronounced sidespin via gear effect. These interactions explain why two golfers using identical clubheads can experience different launch windows and why certain geometries are deliberately biased toward a draw or fade by shifting the aerodynamic and inertial centers-i.e., designs that “exert” a predictable flight tendency under representative swing kinematics.

For design validation and fitting, combined aerodynamic and biomechanical test protocols are essential. Recommended measures include:

- Wind tunnel / moving-plate CFD under controlled yaw and attack-angle sweeps to map lift and drag sensitivity.

- High-speed impact testing with 3D ball tracking to connect face geometry to spin vectors and launch conditions.

- Player-in-the-loop trials to quantify how shaft dynamics and grip-induced kinematics modulate the aerodynamic response in situ.

These complementary methods enable optimization objectives-maximizing carry, minimizing dispersion, and tuning shot bias-to be translated into quantified geometric prescriptions for next-generation clubheads.

Shaft Dynamics and Torsional Characteristics: Effects on energy Transfer and Shot consistency

Contemporary understanding of the golf shaft draws on the general mechanical concept of a shaft as a rotating element that transmits torque and torque-related energy across a linkage. In the context of a golf swing, this transmission is not purely axial or bending-dominated but includes significant **torsional dynamics**, such that the shaft serves both as an energy conduit and as a dynamic filter that modulates the timing, magnitude, and phase of clubhead rotation prior to impact. Quantifying torsional stiffness and the associated damping characteristics is therefore essential to predicting how much of the golfer’s kinetic input is preserved in clubhead speed versus dissipated internally.

Under dynamic loading, torsional deflection interacts with bending modes to produce a phase-dependent clubface orientation at ball-strike. Small variations in torsional phase (on the order of milliseconds) can change face angle and effective loft, altering initial ball direction, backspin, and launch angle. High-frequency measurement systems and finite-element modal analyses reveal that shafts with similar static stiffness profiles can exhibit markedly different dynamic torsional responses, leading to measurable differences in shot dispersion even when swing speed and impact location are held constant.

Primary determinants of torsional behavior include:

- Material anisotropy – fiber architecture and resin matrix define shear modulus and damping.

- Geometry and taper – wall thickness and taper distribute torsional stiffness along the shaft length.

- Length and boundary conditions – shaft length and grip/hosel interface influence modal shapes and frequencies.

- Player-induced torque – grip technique and wrist action change the input torque waveform.

Representative comparative metrics can aid fitting and research.The table below provides concise, illustrative values linking nominal torsional stiffness to a qualitative shot-consistency index. (Values are demonstrative and intended for comparative interpretation rather than absolute specification.)

| Shaft Type | Torsional Stiffness (Nm·deg⁻¹) | Relative Shot Dispersion |

|---|---|---|

| Tour-Stiff (short taper) | 0.095 | Low |

| Mid-Profile (variable layup) | 0.075 | Moderate |

| High-Spin (softer tip) | 0.045 | High |

From a practical fitting and performance perspective, matching torsional properties to a player’s swing tempo and torque profile can reduce dispersion and improve energy transfer efficiency. For players with rapid wrist torque and late release, stiffer torsional profiles can stabilize face orientation; conversely, those with smoother energy transfer may benefit from moderate torsional compliance to optimize launch and spin. Objective fitting should combine on-course dispersion metrics, launch monitor data, and modal characterization of the shaft (natural frequencies, damping ratios, and phase response) to achieve an evidence-based equipment prescription.

Grip Ergonomics and Interface Mechanics for Reducing Unwanted Torque and Improving Control

Hand-club interface mechanics govern the transmission of forces and moments from the golfer to the clubhead; small deviations in grip orientation or pressure distribution produce measurable increases in unwanted torsional moment about the shaft axis. Experimental and modelling work shows that lateral pressure shifts of as little as 10-15% of total grip load create pronounced changes in clubface rotation at impact,increasing shot dispersion. Accordingly, evaluation of interface kinematics should quantify not only gross grip forces but also spatial pressure patterns, contact area, and time-resolved moments to fully characterize the torque-generating potential of a given grip geometry and material.

Design variables-**cross-sectional shape**, **surface texture**, **material compliance**, and **circumferential stiffness**-interact nonlinearly to influence slip tendency and rotational resistance. Softer, higher-friction materials increase contact area and reduce micro-slip, lowering required grip preload and thereby reducing forearm tension. Conversely, excessively compliant grips can allow micro-rotations that amplify torsional impulse at impact. Optimizing the combination of local compliance (for comfort and conformation) with targeted stiffness ribs or channels (for anti-rotation) yields a net reduction in undesired torque while preserving proprioceptive feedback.

Practically implementable strategies that emerge from biomechanical and mechanical analyses include:

- variable-diameter sections to modulate lever arm and hand leverage without increasing overall grip preload.

- Micro-texture zoning to localize friction in high-torque regions (thumb and index pad) while reducing friction where mobility is needed.

- Asymmetric stiffness inserts to bias the club toward neutral face orientation under off-center loads.

- Grip taper optimization to promote consistent wrist-set and reduce pronation/supination excursions during the downswing.

Objective assessment requires synchronized multimodal instrumentation: high-resolution pressure-mapping arrays for spatial contact metrics, inertial measurement units (IMUs) on the hands and shaft for angular velocity and torsional impulse, and high-speed ball/face tracking to link interface events to launch outcomes. The following table summarizes representative metrics and concise interpretation guidelines for fitting and design decisions.

| Metric | Diagnostic Threshold | Design Response |

|---|---|---|

| peak lateral pressure ratio | >0.35 | Increase thumb-pad friction; add medial rib |

| Micro-slip events/frame | >3 per swing | Raise local surface roughness; increase compliance |

| Torsional impulse (N·m·s) | High variability >10% | Broaden diameter; asymmetric stiffness insert |

Implications for practitioners include tailored grip selection during club fitting and the incorporation of grip-targeted drills during instruction to reduce unnecessary preload and excessive wrist torque. from a research perspective, future work should quantify long-term neuromuscular adaptations to grip ergonomies and explore advanced materials with directionally dependent friction and stiffness to further decouple control from unwanted torque generation.

integrated Biomechanical and Aerodynamic Simulations for Predicting Shot Dispersion Under Realistic Conditions

Contemporary studies couple detailed biomechanical representations of the golfer with high-fidelity aerodynamic models of the club-ball system to produce a unified predictive surroundings. The human component uses **multi-body dynamics** and musculoskeletal inverse dynamics to resolve joint torques, shaft kinematics and impact conditions, while the equipment is represented through deformable-body models and computational fluid dynamics (CFD) of transient wake formation. This combined framework-reflecting the dictionary sense of integrated as the coordination of separate elements into a harmonious whole-permits analysis of how subtle changes in clubhead geometry, shaft flexural response and grip contact mechanics jointly determine launch conditions at impact.

to reproduce realistic playing conditions the simulation chain embeds environmental and performer variability. Boundary conditions include wind profiles, temperature-dependent air density, turf-ball interaction coefficients, and realistic grip slip or hand-induced torque. Player variability is introduced via a stochastic sampling of swing kinematics (e.g., tempo, path, face angle) derived from motion-capture populations; **Monte Carlo** sampling of these inputs yields distributions of launch speed, spin vector and impact point rather than single deterministic outputs. The result is probabilistic prediction of shot outcomes that aligns with on-course dispersion observations.

The computational pipeline integrates modular solvers with explicit coupling to capture transient fluid-structure interaction (FSI) during impact and early ball flight. Raw motion-capture and force-plate measurements are processed through inverse dynamics to generate muscle-driven boundary loads for the shaft and clubhead FEA; the instantaneous post-impact ball and club geometry feed a transient CFD solver for the first 0.2 seconds of flight. For suitability in equipment design and fitting, surrogate models-built from high-fidelity runs using proper orthogonal decomposition or Gaussian-process emulators-provide orders-of-magnitude speed-up while preserving critical nonlinearities. **Validation** is performed against launch-monitor and wind-tunnel datasets to quantify model bias and uncertainty propagation to predicted dispersion metrics.

The probabilistic outputs translate directly into performance metrics used by engineers and fitters. The table below illustrates a compact example comparing three conceptual driver configurations; values are illustrative and reflect mean carry distance (m), carry standard deviation (m) and lateral dispersion (m). These metrics support trade-offs between average distance and consistency, and allow computation of shot-shape likelihoods and cluster statistics used in fit decision rules.

| Configuration | Mean Carry (m) | Carry SD (m) | Lateral SD (m) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline Driver | 245 | 12 | 8 |

| Stiffer Shaft | 248 | 10 | 7 |

| Grip-Enhanced ergonomics | 243 | 9 | 5 |

Translated into practice, these integrated predictions yield concrete guidance for equipment development and custom fitting. Key actionable outcomes include:

- Design prioritization: focus geometric changes that reduce aerodynamic sensitivity to small face-angle errors.

- Personalized fitting: match shaft dynamic response to a player’s typical tempo and required shot dispersion envelope.

- Grip optimization: select textures and diameters that minimize micro-slip and reduce lateral spread without degrading release mechanics.

- Field validation loop: deploy short, targeted field campaigns to calibrate surrogate models and update posterior distributions of player variability.

Collectively, the approach demonstrates that melding personalized biomechanics with aerodynamic fidelity produces robust, actionable predictions of shot dispersion under realistic playing conditions, enabling evidence-based decisions across engineering, coaching and fitting workflows.

Experimental Protocols and Wind Tunnel Methodologies for Validating Equipment Performance

Controlled laboratory workflows begin with clear definitions of the test matrix and acceptance criteria for each device under study. Tests are designed to isolate the mechanical degrees of freedom that influence shot outcome (clubhead geometry, shaft bending modes, grip kinematics) while maintaining repeatable environmental conditions. Specimen selection protocols mandate multiple samples per head/shaft/grip configuration and randomized test order to mitigate manufacturing and fatigue bias. **Reproducibility** is assured through documented setup photos, jig specifications, and pre-test verification routines.

Instrumentation and calibration are prioritized to ensure traceable measurements across both biomechanical rigs and aerodynamic facilities.Typical sensor suites include high-speed stereo videography, optical/IMU-based motion capture, 6‑DOF force/torque balances, hot-wire or Cobra probes for wake characterization, and pressure arrays for surface-pressure mapping. All sensors follow a documented calibration schedule; such as,force transducers are zeroed and span-checked before each block,and flow probes are calibrated against a NIST-traceable standard. The term experimental in this context implies systematic manipulation under controlled conditions to quantify cause-effect relationships between equipment variables and performance metrics.

Wind-tunnel protocols emphasize flow fidelity and parameter sweeps that reflect on-course variability. Models are mounted on low-interference sting supports or robotic holders that replicate swing kinematics where feasible. Key test conditions are varied across the following matrix to capture sensitivity:

- Airspeed (Reynolds-number bracketing to capture scale effects)

- Yaw and sideslip angles (to simulate crosswinds)

- Angle of attack and dynamic spin rates (steady and transient)

- Surface roughness states (clean, clubface wear, dimple variations)

Each condition is run in multiple repeats and randomized sequences to support statistical inference.

Data reduction emphasizes uncertainty quantification and transparent reporting. Raw time-series are de-noised with well‑documented filters, ensemble-averaged where appropriate, and subjected to spectral analysis to isolate vibrational coupling between shaft dynamics and aerodynamic forcing. The uncertainty budget is built from sensor specifications, calibration residuals, and sample repeatability; typical target uncertainties for model-scale testing are summarized below.

| Parameter | typical Uncertainty |

|---|---|

| Drag coefficient (Cd) | ±1-3% |

| Lift coefficient (Cl) | ±2-4% |

| Spin rate | ±3-6% |

| Clubhead angle (attitude) | ±0.2° |

Integrative protocols bridge biomechanics and aerodynamics by synchronizing motion-capture timelines with tunnel-based force and pressure recordings. Recommended best practices include instrumenting full swing arcs on multi-axis rigs to capture transient aerodynamics, performing scaled-model validation followed by full-scale spot checks, and publishing complete test matrices with uncertainty bounds. Emphasis is placed on open metadata (mounting geometry, boundary-layer tripping methods, sensor calibration files) so that results can be independently reproduced and meta-analyzed across laboratories.

Data-Driven Fitting Recommendations for Players: Translating Laboratory Metrics to On-Course Outcomes

Laboratory-derived variables must be reframed as actionable fitting targets to influence real-world performance.Core metrics-clubhead speed, ball speed, launch angle, backspin, attack angle, smash factor, and dynamic loft-serve as the translation layer between motion-capture/launch-monitor output and on-course outcomes such as carry distance, landing angle, and dispersion. Interpreting these metrics in isolation risks overfitting equipment to a snapshot of performance; rather, practitioners should use multivariate profiles (e.g., ball speed coupled with spin and attack angle) to predict carry-performance and yardage consistency under varying launch and wind conditions.

Fitting recommendations should prioritize the coupling of aerodynamic and biomechanical determinants. Practical adjustments include:

- Shaft selection: match stiffness and kick point to temporal sequencing and peak angular velocities to preserve energy transfer (maximize smash factor) without inducing timing instability.

- Loft optimization: tune loft to achieve an aerodynamic sweet spot where launch and spin produce ideal carry for the player’s swing-speed envelope.

- Head center-of-gravity (CG) and face technology: alter CG depth/height and face stiffness gradients to modulate spin/pierce and lateral launch for targeted dispersion control.

- Length and lie: set to maintain consistent impact location given the player’s postural geometry and swing arc to reduce toe/heel misses and turf variability.

| Laboratory Metric | Fitting Adjustment | Expected On‑Course Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| Ball Speed | Optimized shaft launch & face loft | Improved carry & total distance |

| Spin Rate | Loft/CG repositioning | Reduced ballooning; predictable rollout |

| Launch Angle | Loft and shaft kick point | Optimized apex and carry consistency |

| Attack Angle | Lie and shaft flex | Improved turf interaction; reduced thin/topped shots |

Player-specific biomechanics must guide how recommendations are prioritized. For a high-swing-speed power player (e.g., >105 mph), the priority is harnessing ball speed with lower loft and a stiffer, lower‑launch shaft while ensuring spin remains within aerodynamic optimums. For an accuracy-oriented moderate-speed player, increasing loft slightly and selecting a shaft that promotes mid-to-high launch and higher smash stability will frequently enough translate to tighter dispersion and more workable trajectory. The fitting process should therefore include an assessment of kinematic sequencing (pelvis-torso-arm timing), wrist-cocking patterns, and ground-reaction force application, as these govern reproducibility of lab metrics on the course.

Validation through on-course or course-like testing is essential to confirm laboratory prescriptions. A concise validation protocol should include:

- Multi-condition sampling: test across at least three wind/lie/tee-height conditions to account for aerodynamic sensitivity.

- Repeated measures: sets of 10-15 shots per club to evaluate consistency, fatigue effects, and dispersion patterns.

- Outcome alignment: compare predicted carry/landing angle from launch data to measured on-course results and iterate equipment parameters.

Only by closing the loop-integrating biomechanical profiling, aerodynamic modeling, and systematic on‑course validation-can fitting recommendations reliably translate laboratory metrics into measurable performance gains and injury‑minimizing movement strategies.

Future Directions in Smart equipment Design and Real-Time Biofeedback for Performance Optimization

Advances in embedded sensing and materials engineering will enable a new generation of clubs and accessories that operate as integrated biomechanical-aerodynamic systems. Miniaturized inertial measurement units (IMUs), pressure-mapping grips, and strain-sensing shafts can be combined to produce **distributed sensing** across the club and player interface. When coupled with onboard microcontrollers and low-power wireless interaction, these elements permit continuous capture of kinematic, kinetic, and vibrational signatures during full swings, enabling richer datasets for both analysis and on-device feedback.

Real-time closed-loop feedback platforms will transform practice paradigms by translating complex sensor streams into actionable cues with low perceptual latency. Multimodal outputs – haptic actuators, spatialized audio, and augmented-visual overlays – can be dynamically tailored by personalization algorithms to accelerate motor learning.Typical modalities and target system requirements include:

- Haptic: ~<10-30 ms actionable latency for feel-based corrections

- Audio: ~<50-100 ms for rhythm and timing cues

- Visual/AR: ~100-200 ms acceptable when combined with predictive modeling

| Modality | Target Latency | Typical Data Rate |

|---|---|---|

| Haptic | 10-30 ms | 100-500 Hz |

| Audio | 50-100 ms | 20-100 Hz |

| Visual/AR | 100-200 ms | 30-120 Hz |

From a design perspective, there is growing interest in **adaptive geometry** and tunable material systems that respond to sensed conditions. Examples include active clubhead faces with micro-actuation to fine-tune local loft and spin characteristics, variable-stiffness shafts that change bending modes mid-swing, and grips that modulate compliance or provide localized tactile cues. These capabilities will require co-optimization of mechanical reliability, power management, and aerodynamic stability to ensure on-course robustness without penalizing mass distribution or swing feel.

The computational backbone for optimizing performance will be hybrid frameworks that integrate high-fidelity CFD, multibody musculoskeletal models, and machine learning-driven surrogate models to enable rapid assay of design and coaching interventions. Key research foci should include:

- Development of validated digital-twin pipelines that reconcile field sensor data with laboratory-scale aerodynamic and biomechanical models

- Transfer-learning strategies to personalize models across skill levels while minimizing calibration burden

- Standards for data interoperability,privacy-preserving model updates,and reproducible performance metrics

Translating laboratory advances into widespread adoption demands a structured roadmap emphasizing rigorous field validation,manufacturability,and accessibility. Priorities include longitudinal studies across diverse player populations, cost-reduction in sensor and actuation subsystems, and industry-wide benchmarks for latency, durability, and safety.By aligning interdisciplinary engineering, sports science, and user-centered design, the next decade can deliver smart equipment and real-time biofeedback systems that measurably enhance consistency, launch optimization, and long-term skill retention.

Q&A

Note on search results

– The web search results provided with your request do not contain material relevant to biomechanics, aerodynamics, or golf equipment; they refer to WhatsApp Web. Accordingly, the Q&A below is produced independently of those search results and is focused on the topic you specified: “biomechanical and Aerodynamic Evaluation of Golf Equipment.”

Q&A: Biomechanical and Aerodynamic Evaluation of Golf Equipment

1. Q: what is the primary objective of a combined biomechanical and aerodynamic evaluation of golf equipment?

A: The primary objective is to quantify how equipment design variables (clubhead geometry,shaft dynamic properties,grip ergonomics) interact with human movement to influence swing efficiency,ball launch conditions (speed,spin,launch angle),and shot dispersion. This integrated approach aims to relate measurable design parameters to performance outcomes and injury risk via experimental and computational methods.2. Q: What hypotheses are typically tested in such a study?

A: Typical hypotheses include: (a) specific clubhead geometries yield higher ball speed and/or more favorable spin characteristics under realistic swing kinematics; (b) shaft stiffness, mass distribution, and torsional dynamics significantly affect energy transfer (smash factor) and shot dispersion; (c) grip size and ergonomics influence wrist kinematics and grip force, thereby affecting consistency and accuracy.

3. Q: What experimental methods are appropriate for the biomechanical component?

A: Common methods include: three-dimensional motion capture (optical marker-based or markerless), wearable inertial measurement units (IMUs), force plates for ground reaction forces, instrumented club shafts or grips with strain gauges and pressure sensors, electromyography (EMG) for muscle activation, and high-speed video for kinematic verification.

4. Q: What techniques are used for aerodynamic testing?

A: Aerodynamic testing typically employs computational fluid dynamics (CFD) to simulate airflow over the clubhead and ball, wind-tunnel testing of clubheads and whole clubs (frequently enough on a swing robot or fixed rig), free-flight indoor telescopic ballistics (stadia or enclosed range with launch monitors), and smoke/particle visualization for flow and separation analysis.

5. Q: How can the interaction between biomechanics and aerodynamics be investigated?

A: Integrative approaches include: (a) coupling measured clubhead kinematics (from human swings) to CFD and rigid-body simulations to predict ball launch and aerodynamic forces; (b) using a robotic swing machine to reproduce representative kinematics and validate CFD predictions under controlled conditions; (c) performing sensitivity analyses that vary both human-derived input (e.g., face angle error, impact location) and equipment parameters (e.g., loft, face curvature) to quantify interaction effects.

6. Q: What metrics are most relevant for performance evaluation?

A: Key performance metrics are clubhead speed, ball speed, smash factor (ball speed/clubhead speed), launch angle, spin rate (backspin and sidespin), aerodynamic drag and lift coefficients, carry distance, total distance, shot dispersion (lateral and longitudinal variability), impact location on face, and temporal metrics (e.g., tempo, downswing duration).

7. Q: How should shot dispersion be quantified?

A: Shot dispersion is quantified statistically (e.g., standard deviation, circular statistics for azimuthal error, bivariate ellipse representing 95% confidence region). Analyses should separate systematic bias (mean miss) from random variability and account for environmental and measurement noise.

8.Q: What biomechanical variables most strongly influence launch conditions?

A: Variables include clubhead speed at impact, face angle and path at impact, angle of attack, impact location on the face, wrist lag and release timing, and grip pressure. Kinetic chain variables-pelvic rotation, trunk rotation, and sequencing/timing of segmental angular velocities-also strongly influence clubhead speed and impact consistency.

9. Q: How do shaft dynamics affect performance?

A: shaft properties (stiffness profile, bending/torsional stiffness, mass distribution, and kick point) influence dynamic deflection and twist during the swing, affecting effective loft at impact, clubface orientation, energy transfer efficiency, and shot dispersion. Flexible shafts can store/release energy but may increase face twist leading to dispersion if not matched to the golfer’s tempo and swing mechanics.

10.Q: What role does clubhead geometry play aerodynamically?

A: Clubhead shape, surface roughness, crown curvature, and back-geometry affect flow separation, pressure distribution, drag, and potential lift (especially for drivers and fairway woods). Perimeter weighting and MOI (moment of inertia) design influence stability during off-center hits and thus dispersion.

11.Q: How does grip ergonomics influence biomechanics and performance?

A: Grip diameter, texture, taper, and surface compliance affect hand placement, wrist mobility, grip force distribution, and proprioception. These factors influence club control, face-square maintenance, timing, and muscle activation patterns, thereby affecting shot consistency and potential overuse injuries.

12.Q: What instrumentation is needed for measuring impact conditions and ball aerodynamics?

A: Required instrumentation includes calibrated launch monitors (radar or photometric) for ball speed, launch angle, and spin; high-speed cameras or Doppler radar for impact event capture; pressure-mapped impact sensors or ball/face contact measurement systems; and wind-tunnel force balances or force/torque sensors for aerodynamic force measurement.

13. Q: How should CFD models be validated?

A: Validation requires comparison with experimental data: wind tunnel force/pressure measurements on clubhead models, flow visualization (PIV-particle image velocimetry), and measured ball flight trajectories under controlled conditions. Grid convergence studies,turbulence model sensitivity analyses,and replication of realistic boundary conditions (relative velocity,spin) are essential.

14. Q: What statistical analyses are appropriate?

A: Analyses should include repeated-measures ANOVA or linear mixed-effects models to account for within-subject variability, regression and multivariate analyses to identify predictors of performance, principal component analysis for dimensionality reduction of kinematic data, and bootstrapping for confidence intervals when distributions are non-normal. Effect sizes and power analyses are necessary for sample-size justification.

15.Q: How many participants and swings per participant are typically required?

A: Sample size depends on expected effect sizes and variability. For within-subject comparisons, 12-30 experienced golfers with 30-50 swings per condition (after warm-up and familiarization) often provide sufficient statistical power; however, pilot data and power calculations should guide exact numbers.For equipment-only aerodynamic tests,multiple repeats of each test condition are required to estimate measurement repeatability.

16. Q: What are common sources of measurement error and how are they mitigated?

A: Sources include marker occlusion and soft-tissue artifact (motion capture), sensor drift (IMUs), calibration errors (launch monitors), environmental variability (indoor vs outdoor wind), and manufacturing tolerances (clubhead). Mitigation strategies include sensor fusion, filtering, calibration protocols, rigid cluster markers, repeated trials, and reporting measurement uncertainty.

17. Q: How should off-center impacts be treated in analysis?

A: Off-center impacts should be quantified (e.g., radial distance from sweet spot) and either included as covariates in models or analyzed in separate conditions. Statistical models can partition variance attributable to impact location; MOI and face flexural characteristics should be considered when interpreting off-center performance.

18. Q: What design recommendations can be derived for club manufacturers?

A: Recommendations include optimizing clubhead aerodynamic shapes to reduce drag while maintaining stable flight, tuning mass distribution to increase MOI without unduly compromising energy transfer, matching shaft stiffness and torque to typical swing tempos of target golfer categories, and designing grips that promote neutral wrist kinematics and cozy, repeatable grip pressures to reduce dispersion.

19. Q: What coaching implications arise from the integrated analysis?

A: Coaches can use quantified relationships between kinematics and launch conditions to individualize equipment selection (e.g., shaft flex, loft adjustments), target swing adjustments that improve launch and spin profiles, and emphasize grip and wrist mechanics for consistency. Objective feedback from launch monitors and motion capture can accelerate skill transfer.20. Q: How do you account for individual variability in equipment fitting?

A: Individual variability is addressed by profiling a golfer’s kinematics (tempo,clubhead speed,attack angle),anthropometrics (hand size,limb lengths),and skill-level (repeatability). Multi-factor optimization (e.g., using bayesian or multi-objective optimization frameworks) can recommend equipment configurations that balance distance, dispersion, and joint loading.

21. Q: What safety and ethical considerations should be observed?

A: Ensure informed consent, screening for injury risk, appropriate warm-up protocols, and monitoring for fatigue. Data privacy and secure storage of participant data, and ethical use of human subject data in publication, must be maintained.

22. Q: What are the main limitations of current integrated studies?

A: Limitations include laboratory constraints that may not capture on-course variability, difficulty replicating the full complexity of human-equipment interaction in simulations, limited generalizability across skill levels, potential simplifications in CFD (e.g., steady-state assumptions), and measurement uncertainties in biomechanical data.

23. Q: What future directions are recommended for research?

A: Future work should expand participant diversity (age, sex, skill), integrate markerless capture and real-time biomechanical feedback, couple high-fidelity fluid-structure interaction (FSI) simulations with musculoskeletal models, investigate long-term effects on injury risk, and adopt open-data protocols to improve reproducibility.

24. Q: How can practitioners replicate the study?

A: Provide detailed protocols for participant selection, warm-up, swing standardization, instrumentation calibration (motion capture, launch monitors, wind tunnel/CFD settings), data processing pipelines, and statistical models. Share raw and processed datasets, code for analysis, and model parameters where possible to facilitate replication.

25.Q: What constitutes a triumphant outcome of such a study?

A: A successful outcome demonstrates clear, statistically supported links between equipment parameters, biomechanical variables, and aerodynamic/ball-flight outcomes; produces actionable recommendations for equipment design and fitting; and advances understanding of how to optimize performance while minimizing injury risk, presented with reproducible methods and transparent uncertainty quantification.

if you would like, I can:

– Draft a concise methods template (participant protocol, instrumentation, CFD/wind-tunnel setup) you could adapt for a manuscript.

– Construct example statistical analysis code (pseudocode or R/Python) for mixed-effects modeling of launch outcomes.

– Produce a brief executive summary of findings suitable for industry stakeholders.

To Conclude

The provided web search results returned pages related to Rolex timepieces and did not contain material pertinent to biomechanical or aerodynamic studies of golf equipment. Below is an academic, professional outro for the article you requested.

this integrated biomechanical and aerodynamic evaluation elucidates how clubhead geometry, shaft dynamics, and grip ergonomics jointly determine swing efficiency, ball launch characteristics, and shot dispersion. The combined modelling and empirical testing approach demonstrates that small geometric and material modifications can produce measurable changes in launch conditions and dispersion patterns,while individual biomechanical variability mediates the realized performance gains. These findings underscore the need for equipment design strategies that reconcile aerodynamic optimization with the dynamic constraints of human motor control. Limitations of the present study include the controlled laboratory conditions, the sample size and skill-level distribution of participants, and simplifications inherent in the modelling framework; addressing these will be essential to improve ecological validity and generalizability. Future work should pursue larger, more diverse subject cohorts, in-situ field testing across a broader range of environmental conditions, and the integration of real-time biomechanical feedback to enable personalized equipment tuning. Collectively, such advances will better inform evidence-based design and fitting protocols that enhance performance while respecting individual biomechanics and playability.

Biomechanical and Aerodynamic Evaluation of Golf Equipment

Why biomechanics and aerodynamics matter for golf equipment

Golf performance is the product of human biomechanics interacting with engineered equipment and the air. Optimizing clubhead geometry, shaft dynamics, and grip ergonomics can increase ball speed, improve launch conditions, reduce dispersion, and make a golfer more consistent. This article breaks down the science and gives practical fitting and testing steps to improve your game with better equipment choices.

Key golf keywords to keep in mind

- Clubhead design, center of gravity (CG), moment of inertia (MOI)

- Shaft flex, torque, kick point, swingweight

- launch monitor metrics: ball speed, clubhead speed, launch angle, spin rate, smash factor

- Aerodynamics: drag coefficient (Cd), lift, dimples, airflow separation

- Shot dispersion, shot shaping, shot consistency, ball flight

- Grip size, grip tape, grip pressure, ergonomics

Measurement tools and testing protocol

Reliable evaluation requires objective measurement. Use a combination of biomechanical and aerodynamic tools:

- Launch monitors (TrackMan, GCQuad) – measure ball speed, spin, launch angle, carry distance, smash factor, and dispersion.

- High-speed cameras and motion capture – analyze clubhead path, face angle at impact, wrist angles, and kinematic sequencing.

- Force plates and pressure mats – measure ground reaction forces, weight transfer, and balance during the swing.

- Wind tunnel and CFD – test clubhead aerodynamics, drag (Cd) and lift (Cl) characteristics; evaluate golf ball dimple effects.

- Shaft analyzers – measure dynamic flex, vibration frequency, torque under load, and kick point effects on release timing.

Clubhead geometry: what to evaluate and why

Clubhead characteristics drive the ball’s initial conditions and, together with player kinetics, determine carry and dispersion.

Notable clubhead parameters

- Loft and face angle: Determine launch angle and sidespin. Loft influences spin and apex; face angle at impact controls initial direction.

- Center of gravity (CG): Forward CG lowers spin and tightens dispersion; rear CG increases launch and forgiveness.

- Moment of inertia (MOI): Higher MOI reduces twisting on off-center hits (less dispersion).

- Face radius,bulge and roll: Effect directional curvature for off-center strikes and help predict shot shape.

- Head shape and aerodynamics: Streamlined head shapes and turbulators can reduce aerodynamic drag, increasing clubhead speed through the swing.

Shaft dynamics: how shaft choice alters performance

The shaft is the dynamic link between the golfer and the clubhead. Small changes in shaft properties can considerably affect timing,energy transfer,and shot dispersion.

key shaft properties

- Flex: Influences launch and timing. Stiffer shafts favor faster swing speeds and lower launch/spin; softer shafts can increase launch angle for moderate swing speeds.

- Torque: Controls feel and face rotation – higher torque can increase face closure and promote hooks for some players.

- Kick point (bend point): Higher kick point produces lower trajectory; low kick point increases trajectory.

- Length and swingweight: Longer shafts can increase clubhead speed but may reduce accuracy and timing.

- Damping and vibration: Affect feel and feedback. Better damping can reduce undesirable vibrations on miss-hits.

grip ergonomics and how they affect consistency

A properly sized and positioned grip reduces compensations in the hands and wrists, producing more consistent face orientation at impact.

Grip considerations

- Grip size: Too small promotes wrist action and potential hooks; too large can restrict release and create pushes. Most golfers benefit from a mid-size grip tuned to hand size.

- Texture and material: Provide traction and influence grip pressure. Synthetic, tacky materials require less squeeze than worn rubber grips.

- Grip alignment and rotation: Slight adjustments in grip rotation change face angle at address and at impact, affecting shot shape.

- Grip pressure: Measured with pressure sensors – consistent and moderate pressure helps timing and energy transfer.

How biomechanics governs swing efficiency

biomechanics evaluates how the body generates and transfers energy through the kinetic chain – from ground reaction forces to clubhead speed at impact.

Biomechanical variables to monitor

- Ground reaction and weight shift: Proper lateral and rotational force transfer improves hip-to-shoulder sequencing and clubhead speed.

- Segmental sequencing: Pelvis -> torso -> led arm -> club – timing is crucial; mis-timed sequencing reduces smash factor.

- Wrist release timing: Determines dynamic loft and face angle. shaft flex interacts with release timing to affect launch and spin.

- balance and posture: Poor posture forces compensations that increase dispersion and reduce distance.

Aerodynamics of the golf ball and clubhead

Aerodynamic behavior determines how the ball travels after launch and how the club moves through the air during the swing.

Golf ball aerodynamics

- Dimples: Promote a turbulent boundary layer that delays separation, reducing drag and optimizing lift for carry.

- Spin: Backspin creates lift (carry); sidespin creates curvature (draw/fade) and affects dispersion.

- Reynolds number and airflow: Speed and atmospheric conditions change the ball’s behavior; launch monitors must consider density and altitude.

Clubhead aerodynamics

- Drag on the clubhead reduces how fast the head can move through the target zone; aerodynamic shaping can add measurable clubhead speed through less air resistance.

- Surface textures and crown features (e.g.,turbulators) can alter flow,stabilize the swing path at higher speeds,and slightly influence feel.

Metrics that connect equipment to outcomes

- smash factor = Ball speed / Clubhead speed – efficiency of energy transfer.

- Launch angle & spin rate – Together determine carry, apex, and roll.

- Carry distance & total distance – The practical outcomes golfers care about.

- Shot dispersion (grouping) – Standard deviation of shot azimuth and landing position; lower dispersion means more accuracy.

- Face-to-path at impact – Primary determinant of initial direction and curvature.

Fitting recommendations and practical testing tips

Follow a structured fitting protocol to match biomechanical profile and aerodynamic behavior to equipment.

- Start with a baseline launch monitor session with your current driver, 7-iron, and wedges to capture ball speed, launch, spin, and dispersion.

- assess body mechanics with a coach or motion capture: identify swing speed, release timing, and balance issues.

- Test different shaft flexes, lengths, and kick points-only change one variable at a time and collect 10-15 shots per configuration.

- Try clubheads with different CG and MOI settings or adjustable weights to find the best compromise between spin and forgiveness.

- Evaluate grip size and pressure changes – re-test launch monitor metrics and dispersion.

- Use video and face-impact tape to confirm center-strike frequency and face angle at impact.

Simple WordPress-style table: Equipment parameter vs.typical effect

| Parameter | Typical effect | Player tip |

|---|---|---|

| Forward CG | Lower spin, lower launch | Good for high-spin drivers |

| Rear CG | Higher launch, more forgiveness | Helps slower swing speeds |

| Stiffer shaft | Lower launch, less spin | use if swing speed > 95 mph |

| Larger grip | Limits release, can reduce hooks | Try +1/16″ for strong hands |

Case studies and examples

Case study 1: Driver CG shift reduces spin and tightens dispersion

A recreational player with 92 mph driver speed experienced 3000+ rpm driver spin and high dispersion. Using a driver with a forward CG setting (adjustable weight moved forward), tests showed:

- spin reduced from 3200 rpm to 2600 rpm.

- Average carry increased by 6-10 yards due to reduced spin-induced ballooning.

- Shot dispersion (lateral standard deviation) tightened by ~12% as shots flew more predictably.

Case study 2: Shaft flex and kick point tuning

An intermediate player with moderate swing speed (85-92 mph) moved from a regular flex, mid-kick-point shaft to a slightly softer tip and lower kick point. results:

- Launch angle increased ~1.5 degrees and spin rose modestly, leading to an extra 8-12 yards carry.

- Smash factor stayed consistent, but feel and confidence improved due to smoother timing.

First-hand fitting experience: checklist for on-course testing

- Test on a launch monitor at the range,then validate on-course where wind and lie change results.

- Record 8-12 shots per configuration to average out variability.

- Re-check dispersion-tight groups are usually more valuable than a few long outliers.

- Consider comfort and feel; confidence with equipment lowers mental noise and improves routines.

Practical benefits and takeaways for golfers

- Optimized equipment increases distance and reduces dispersion, saving strokes and improving scoring potential.

- Biomechanical matching prevents injury by ensuring equipment complements natural swing mechanics.

- Aerodynamic improvements (even small reductions in drag) can produce measurable clubhead speed gains.

- Regular re-fitting as swing speed and body change (age, fitness) keeps performance optimized.

further reading and next steps

To apply these principles right away:

- Book a session with a certified club fitter and bring launch monitor data.

- Work with a coach to correct major biomechanical faults before over-investing in equipment changes.

- Try small changes (grip size, minor shaft tweaks) first, measure results, then progress to head changes.