Introduction

Understanding the golf swing through the lens of biomechanics affords a systematic pathway to improve precision, consistency, and performance. Biomechanics-defined as the submission of mechanical principles to biological systems-provides the conceptual and methodological tools to quantify motion, force, and muscular coordination during sporting tasks [2,3].Historically rooted in observational and analytical inquiry from figures such as Leonardo da Vinci and Galileo, contemporary biomechanical analysis leverages motion capture, force platforms, and electromyography to translate complex human movement into measurable variables [1]. The follow-through phase of the golf swing, far from being merely the residual motion after ball impact, encapsulates the terminal expression of kinematic sequencing, kinetic transfer, and neuromuscular control that together determine ball flight and shot reproducibility.

This article examines biomechanical strategies for optimizing the follow-through by integrating kinematic descriptions (segmental rotations,angular velocities,clubhead path),kinetic considerations (ground reaction forces,moments,and impulse),and muscle coordination patterns (timing of proximal-to-distal activation and eccentric control during deceleration). Emphasis is placed on how these elements interact to influence clubface orientation at and after impact, center-of-mass trajectory, and postural stability-parameters that correlate strongly with shot dispersion and injury risk. Drawing on principles from biomechanics and biomechanical engineering,we frame practical implications for coaching,training progression,and individualized intervention design [4].

We conclude by outlining measurement approaches and evidence-based drills that translate biomechanical insights into actionable practice. By grounding technical instruction in mechanistic understanding,coaches and practitioners can more precisely target the motor patterns and force-generation strategies that underpin reproducible,efficient follow-throughs and,ultimately,improved on-course performance.

Kinematic Analysis of Trunk Rotation and Its Influence on Post Impact Trajectory

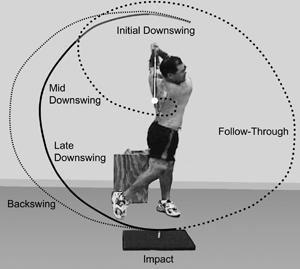

The trunk serves as the primary rotary link in the proximal-to-distal kinetic chain, mediating torque transfer from the lower extremities to the upper limb and club. Quantitative kinematic analysis emphasizes the importance of axial rotation about a stable vertical axis combined with controlled lateral flexion and extension for consistent post-impact trajectories. Key descriptors used in motion analysis include angular displacement, angular velocity, and the timing of peak rotation relative to ball impact. Variability in any of these parameters alters the vector of force application at ball contact, with measurable effects on launch angle and spin characteristics.

High-fidelity motion-capture studies consistently show a temporal dissociation between pelvic and thoracic rotation, commonly referred to as the X‑factor, that modulates elastic energy storage and release.optimal sequencing usually involves early pelvic rotation followed by a rapid thoracic unwinding,producing a high peak in trunk angular velocity just before impact. The following concise table summarizes typical kinematic benchmarks and their qualitative influence on post-impact behavior:

| Metric | Typical Range | Influence on Trajectory |

|---|---|---|

| X‑factor (TORQUE SEPARATION) | ~20-45° | Higher values increase stored elastic energy; can raise ball speed if timed well |

| Peak trunk angular velocity | ~400-900°/s | Correlates with clubhead speed and spin generation when synchronized with wrist release |

| Trunk lateral tilt at impact | ~5-15° | Alters attack angle and launch, influencing carry distance |

the specific sequencing of axial rotation directly affects clubface orientation and path at impact, thereby shaping curvature and lateral deviation of the ball. For example, premature thoracic rotation relative to pelvis reduces the effective X‑factor, diminishing stored elastic recoil and often resulting in lower ball speed and a tendency toward an open face at impact. Conversely, an aggressive delayed thoracic release can accelerate the hand-wrist system into impact, increasing side spin if the face-path relationship is not controlled. Thus, fine-grained temporal coordination-not simply magnitude of rotation-is a principal determinant of post-impact trajectory quality.

From a performance and safety viewpoint, controlled deceleration in the follow-through is essential to dissipate rotational energy without incurring excessive eccentric loads on the lumbar spine and oblique musculature. Rehabilitation and conditioning programs should therefore target both mobility (thoracic rotation, hip internal/external rotation) and eccentric strength (rotational core, posterior chain) to support high-velocity rotation while minimizing injury risk such as lumbar strain or discogenic irritation. Practical monitoring should include:

- Temporal sequencing (pelvis → thorax → arms)

- Peak angular velocities and their timing relative to impact

- X‑factor magnitude and controlled recoil

- Balanced follow-through posture

These metrics inform targeted drills and progressive loading to optimize trajectory outcomes while protecting the lumbar region.

Optimizing Arm Extension and Club Path Through Segmental Coordination

Proximal-to-distal sequencing governs the transfer of angular momentum from the pelvis through the thorax to the upper limbs and clubhead; optimizing this temporal cascade is essential for consistent arm extension and a repeatable club path. Precise phase relationships-pelvic rotation leading thoracic rotation, followed by scapulothoracic reorientation and humeral acceleration-produce a compact yet accelerating kinematic chain.Disruption in any proximal segment timing produces compensatory distal motion (excessive early wrist release or late elbow extension) that alters the clubhead arc and degrades directional control.

From a segmental mechanics perspective, arm extension must be coordinated with trunk deceleration to maintain a stable impact line. The lead arm should exhibit controlled extension through the moment of impact while the trail arm supports torque generation without premature collapse. Proper scapular positioning and glenohumeral centration reduce transverse plane variance, aligning the clubshaft with the intended swing plane and minimizing face-angle deviations that cause lateral dispersion.

Neuromuscular sequencing underlies these kinematic objectives: timely activation of the hip rotators and external obliques initiates rotation, followed by concentric activation of the latissimus dorsi and pectoralis major to accelerate the humerus. Subsequent eccentric control by the rotator cuff and forearm pronators modulates wrist position and clubface orientation. Practically, hitters should focus on controlled trunk deceleration cues and a late, coordinated pronation to square the face-techniques that have measurable links to reduced variability in launch direction.

Training progressions that reinforce segmental timing and arm extension should be systematic and task specific. Useful interventions include:

- Split-hand drill – promotes independent lead-arm extension while preserving torso rotation.

- Towel-under-arm – encourages scapulothoracic coupling and discourages early arm separation.

- Impact-bag contact – develops feel for forward shaft lean and synchronized trunk deceleration.

- slow-motion sequencing with video feedback – isolates timing errors and refines intersegmental delays.

Each drill emphasizes temporal control over brute force, progressively restoring an efficient proximal-to-distal pattern under varying loads and speeds.

Below is a concise reference of key kinematic markers and practical coaching cues to monitor during training:

| Kinematic Marker | Target/Observation | Coaching Cue |

|---|---|---|

| Pelvis→Thorax delay | ~20-50 ms lead | “Lead with the hips,then shoulders” |

| Lead-arm Extension | Controlled extension at impact | “Reach through the ball,don’t snap” |

| Wrist Pronation Timing | Late,rapid pronation post-impact | “Rotate the forearm after impact” |

Role of Wrist pronation and Forearm Mechanics in Clubface Stability

Precise modulation of forearm rotation during the follow-through is a primary determinant of clubface orientation at impact and in the immediate post-impact window. The wrist is not a single hinge but a complex articulating structure of eight carpal bones, and its kinematic behavior is coupled to pronation-supination of the radius and ulna. Small degrees of uncontrolled pronation or supination immediately after impact amplify angular deviations at the clubhead,translating into lateral dispersion of ball flight even when pre-impact mechanics appear sound.

Neuromuscular sequencing that coordinates trunk deceleration, elbow extension and controlled wrist pronation preserves face alignment through release. The pronator musculature of the forearm must generate a stabilizing torque that resists excessive supination during release while permitting a smooth,accelerated rotation of the shaft. Because the carpus distributes loads across multiple small bones and joint surfaces, healthy forearm mechanics reduce localized shear and torsional stresses that can otherwise alter transient clubface angles during the milliseconds following impact.

- Feel cue: allow the lead wrist to rotate gently around the shaft axis rather than flip-this promotes a stable face trajectory.

- drill: slow-motion half-swings where the forearm rotation is emphasized, focusing on smooth pronation through finish.

- Strength cue: progressive pronator/supinator resistance work to increase control under speed.

Quantitatively, three mechanical variables predict post-impact face stability: magnitude of wrist pronation through follow-through, timing of peak pronation relative to impact, and forearm stiffness (rotational stiffness about the longitudinal axis).The table below summarizes typical directional effects observed in biomechanical testing and coaching interventions. Coaches can use these simple metrics to structure feedback and measurable practice goals.

| Variable | Desired Range/Behavior | Effect on Face Stability |

|---|---|---|

| Wrist pronation magnitude | Moderate, smooth | Reduces open/close oscillation |

| Timing of pronation | Peaks just after impact | Maintains consistent launch direction |

| Forearm rotational stiffness | Controlled, trainable | Limits unwanted twist under load |

Clinicians and coaches should integrate mobility, sensorimotor control and progressive loading to optimize forearm mechanics while monitoring for symptoms. The scaphoid and other carpal elements are predisposed to overuse and acute injury when abnormal torsional loads occur at the wrist; persistent pain or instability warrants medical evaluation. Training programs that combine targeted pronator/supinator strengthening, dynamic stability drills and gradual transfer to full-velocity swings produce the best balance of power and repeatable clubface control.

Lower Limb Stabilization and Ground Reaction Force Utilization During Follow Through

The distal segments of the lower extremity act as the primary interface with the ground and therefore critically determine the magnitude and direction of resultant ground reaction forces (GRFs) during the finishing phase of the swing. Precise timing of foot contact, foot pressure redistribution (center of pressure progression), and limb stiffness modulate the ability to redirect kinetic energy produced proximally. Empirical studies indicate that transient increases in vertical and posterior GRF components occur immediately after ball release; these impulses must be absorbed or re-directed through coordinated eccentric action to preserve postural equilibrium and shot dispersion.Maintaining an appropriate base of support reduces multiaxial perturbations and facilitates consistent shot outcomes.

Effective follow-through mechanics require coordinated bracing of the lead limb and graduated loading of the trail limb to create a controlled deceleration pathway for the torso and upper limbs. The lead hip and knee typically assume an **eccentric load** to arrest residual rotational momentum,while the ankle complex modulates medio‑lateral stability through rapid adjustments in inversion/eversion and plantarflexion/dorsiflexion moments. excessive co-contraction in the lower limb musculature can elevate joint compressive loads and degrade fine motor control; conversely, insufficient stiffness compromises force transmission and spatial accuracy. Optimal performance thus necessitates a balance between controlled compliance and supportive rigidity.

Quantitative targets for lower-limb contributions can be conceptualized to guide training and biofeedback.The table below summarizes representative roles and relative GRF magnitudes observed in biomechanical analyses of skilled performers.

| Segment / Muscle group | Primary Function | Relative GRF Role |

|---|---|---|

| Lead Leg (Hip/Knee) | Eccentric deceleration, load acceptance | ↑ Vertical & posterior |

| Lead Ankle | Balance, COP progression | Stabilizing (medio‑lateral) |

| Trail Leg | Push‑off and dissipation of rotational energy | Transient anterior-posterior impulses |

From a training and coaching perspective, targeted interventions can refine the lower limb’s capacity to utilize GRFs effectively. Recommended strategies include:

- Progressive unilateral strength work to enhance single‑leg bracing (e.g., single‑leg squats, Romanian deadlifts);

- Reactive plyometrics emphasizing controlled landing mechanics to train eccentric absorption;

- Balance and proprioception drills with perturbations to accelerate COP adjustments (e.g., wobble‑board tasks, narrow stance swings);

- Tempo and deceleration drills on the course that isolate follow‑through timing.

Coupling these exercises with real‑time feedback (pressure insoles,force plates) accelerates motor learning and transfer to on‑course behavior.

Integrating lower‑limb stabilization principles into a comprehensive follow‑through strategy also reduces injury risk by managing peak joint loads through coordinated eccentric control and GRF routing. Monitoring variables such as lateral GRF spikes, asymmetrical COP shifts, and excessive knee valgus during deceleration can identify maladaptive patterns early. Practitioners should emphasize progressive loading,neuromuscular control,and sport‑specific transfer-preserving the golfer’s ability to dissipate residual energy while maintaining alignment and temporal sequencing for repeatable accuracy.

Neuromuscular Timing and Muscle Activation Patterns for Consistent Follow Through

Neuromuscular timing governs the translation of stored elastic energy and segmental momentum into a reproducible post‑impact trajectory. Electromyographic (EMG) studies indicate that accuracy is tightly coupled to the temporal relationship between preparatory stabilisation and phasic propulsion: well‑timed anticipatory postural adjustments (APAs) precede rapid rotational acceleration, while finely timed phasic bursts in prime movers coincide with maximal clubhead velocity.Deviations of only a few milliseconds in onset or inter‑muscle phase can shift the resultant clubface orientation at impact, producing measurable dispersion in launch direction and spin characteristics.

Representative activation sequencing can be summarised to guide applied assessment and coaching. The table below presents a concise, illustrative ordering of dominant muscle groups with approximate onset relative to peak clubhead velocity. Values are schematic and intended for programming reference rather than as absolute norms.

| Relative phase | Primary Muscle Group | Typical Onset (ms before peak) |

|---|---|---|

| Preparatory | Gluteus medius / erector spinae | ~120-80 |

| Drive | External obliques / rectus abdominis | ~80-40 |

| Transfer | Latissimus dorsi / pectoralis major | ~40-10 |

| Release | Forearm pronators / wrist extensors | ~10-0 |

Consistent follow‑through depends not only on the order of activation but on pattern stability: lower between‑trial variability in onset latency and burst duration predicts tighter shot groups. Effective patterns typically combine a proximal‑to‑distal sequencing strategy with selective co‑contraction of trunk stabilisers (to resist excessive lateral flexion) and phasic relaxation of distal musculature to permit rapid wrist release. Excessive co‑contraction at the wrist or forearm increases moment of inertia and reduces fine motor adjustments, while insufficient trunk stiffness permits unwanted yaw and lateral tilt.

Training interventions that target temporal fidelity and muscle coordination should be multimodal and progressive. Practical modalities include:

- Metronome tempo drills to reduce timing variability and instil a consistent rhythm;

- Medicine‑ball rotational throws emphasizing rapid trunk‑to‑arm energy transfer;

- Resisted follow‑throughs (bands/cables) to enhance eccentric control of the deceleration phase;

- EMG biofeedback sessions for athletes with persistent timing errors to directly visualise onset and amplitude;

- Fatigue‑controlled sets to evaluate timing degradation and inform session volume.

From a coaching and periodisation standpoint, quantify progress with repeatable metrics (onset latency SD, peak activation amplitude, inter‑muscle phase angle) obtained via high‑speed kinematics and portable EMG systems. Establish normative intra‑athlete thresholds (e.g., <10 ms onset SD across trials) before advancing load or speed. integrate timing work into skill sessions rather than isolating it: transfer to the full swing is maximised when temporal refinement co‑occurs with realistic swing dynamics and perceptual demands.

Integrating Flexibility and Mobility Training to Enhance Follow Through Range and Accuracy

Optimizing the terminal phase of the swing requires a coordinated program that reconciles soft‑tissue extensibility with joint centration and motor control. When flexibility and mobility training are purposefully combined with skill rehearsal, athletes attain improved kinematic sequencing in the follow‑through, facilitating consistent clubhead deceleration profiles and repeatable ball launch parameters. Empirical models of swing mechanics indicate that modest gains in segmental range-particularly in the trunk and lead shoulder-translate to measurable reductions in lateral clubface deviation at impact; thus, interventions should prioritize both passive range and active control.

key anatomical constraints that limit follow‑through fidelity include restricted **thoracic rotation**, diminished **hip internal/external rotation**, reduced **scapulothoracic upward rotation**, and wrist terminal range limitations. Tissue stiffness, fascial continuity across the posterior chain, and neuromuscular inhibition patterns interact to produce compensatory motion at the lumbar spine or lead elbow-compromises that increase shot dispersion. Addressing these constraints requires assessments that separate true joint mobility from guarded movement due to pain or poor motor patterns.

Programmatic design must adhere to principles of specificity, progressive overload, and integration. Recommended structural components include:

- Dynamic pre‑shot mobility (short routines that prime range and proprioception immediately before play);

- End‑range control drills (isometric holds and slow eccentrics to stabilize new ranges);

- Rotational strength integration (anti‑rotation and loaded rotation patterns to translate mobility into force control);

- Periodized emphasis (higher frequency and volume in off‑season, maintenance during competitive blocks).

Practical exercise prescriptions should be concise, reproducible, and measurable.Example progressions-beginner to advanced-employ graded complexity and load while maintaining swing specificity. Below is a succinct implementation table that can be incorporated into weekly planning.

| Exercise | Progression | recommended Frequency |

|---|---|---|

| Thoracic rotational mobilization | Seated -> Half‑kneeling -> Medicine‑ball throw | 3x/week |

| Lead hip internal rotation drill | Passive stretch -> Active control -> loaded lunge twist | 2-3x/week |

| Scapular upward rotation control | Scap punches -> Banded rows -> Overhead carries | 2x/week |

Outcomes should be quantified and tracked: use simple range‑of‑motion metrics (target +8-12° thoracic rotation baseline improvement), movement quality scores from video analysis, and performance endpoints such as lateral dispersion (yards) and launch‑angle variance. Clinically meaningful change is best judged over 6-12 weeks with iterative adjustments; sustained enhancements in mobility combined with targeted motor control typically yield improved follow‑through amplitude, reduced compensatory lumbar rotation, and greater shot accuracy.

Specific Drills and Progressive training Protocols to Reinforce Biomechanically Efficient Follow Through

The training program is structured around three biomechanical objectives: stable trunk rotation through impact, controlled arm extension to preserve swing arc, and timed wrist pronation to square the clubface.Each drill is selected to isolate and then integrate these components, with explicit motor learning progressions from slow, conscious repetitions to full-speed ball-striking. Emphasis is placed on measurable outcomes-clubhead path consistency, impact alignments, and launch-angle repeatability-so that adaptations can be quantified and trained systematically.

isolation drills are prescribed to target single-joint or single-segment control prior to integrated practice. Examples include:

- Half-rotation trunk turns against a resistance band (3×8, focus: core sequencing)

- Lead-arm extension holds on a mirror or camera (4×6, focus: maintenance of radius)

- Slow-motion pronation drills with an iron and taped visual cue on the shaft (5×5, focus: timing and forearm rotation)

These unweighted, high-fidelity repetitions train proprioception and neuromuscular timing without the confound of high-speed dynamics.

Progressive integration follows a staged protocol that transitions athletes from segmental control to dynamic coordination. the table below summarizes a four-week mesocycle template with targets for volume, intensity, and primary biomechanical focus.Use video feedback and a simple launch monitor to confirm that trunk rotation peaks slightly after impact, arm extension completes through wrist hinge release, and pronation begins within 20-40 ms of impact for optimal face closure timing.

| Phase | primary Drill | Weekly volume |

|---|---|---|

| Foundation | Resistance band trunk rotations | 3 sessions |

| Integration | Mirror lead-arm holds + slow swings | 3-4 sessions |

| Power | Weighted release swings + impact tape | 2-3 sessions |

| On-course | Simulated pressure play | 1-2 sessions |

Monitoring and progression decisions are guided by objective and subjective metrics: target a 5-10% week‑over‑week increase in full-speed swing repetitions, a reduction in lateral deviation at impact as measured on camera, and a consistent ball-flight dispersion metric from the launch monitor. For golfers of differing abilities, scale intensity by altering resistance, club mass, and environmental constraints (e.g., mats vs. turf). Integrate periodic retention tests (48-72 hours post-training) to ensure motor consolidation; if errors reappear, regress to the previous phase and increase deliberate, feedback-rich repetitions focusing on the specific biomechanical deficit.

Biomechanical Assessment and Technology Assisted Feedback for Individualized Technique Adjustment

Contemporary assessment protocols combine laboratory-grade and field-capable measurement systems to quantify the follow-through as a multisegmental, time-dependent phenomenon. High-speed volumetric motion capture and inertial measurement units (IMUs) provide complementary kinematic streams,while force plates and instrumented clubs quantify kinetics and club-ball interaction. Surface electromyography (sEMG) resolves activation timing of primary contributors (trunk rotators, shoulder stabilizers, wrist pronators) and, when fused with kinematics, enables identification of neuromechanical coordination patterns that underlie consistent follow-through mechanics. Data fusion and inverse dynamics modeling translate raw signals into actionable metrics for coaching and rehabilitation, and the following modalities are commonly integrated into contemporary pipelines:

- Volumetric motion capture (3D joint kinematics)

- Wearable IMUs (on thorax, pelvis, lead arm, and lead wrist)

- sEMG (timing and intensity of muscle groups)

- Force/pressure sensing (ground reaction and grip dynamics)

Quantitative targets are framed as both absolute values and individualized deviations from an athlete’s baseline. Typical kinematic and kinetic variables of interest include peak trunk rotation velocity, lead-arm extension angle at ball release, wrist pronation angular velocity during follow-through, clubhead speed, and ground reaction force symmetry. The table below summarizes representative sensors, derived metrics, and pragmatic threshold values used to guide technique adjustment in the follow-through phase.

| Sensor | Primary Metric | Practical Threshold |

|---|---|---|

| IMU (thorax) | Peak rotation vel. (°/s) | 650-900 |

| sEMG (wrist extensors) | Onset timing (ms) | <40 ms pre-impact |

| Instrumented club | Clubhead speed (mph) | ±5% of baseline |

Real-time and near-real-time feedback modalities facilitate rapid motor learning when they are carefully matched to the athlete’s learning stage.Augmented visualizations such as trajectory overlays and segmental angle traces aid cognitive understanding in early stages, whereas haptic (vibrotactile) cues and low-latency auditory tones support automatization by providing succinct error signals during practice swings. Closed-loop systems that adapt cueing frequency (fading,summary feedback) and modality according to performance variability produce superior retention and transfer to on-course conditions.

An individualized adjustment protocol proceeds from diagnostic profiling to iterative intervention and reassessment. Coaches should prioritize (1) stabilizing intersegmental timing, (2) optimizing end-range lead-arm extension without compensatory lateral flexion, and (3) fine-tuning wrist pronation velocity to match desired launch conditions. Practical recommendations include task constraints (reduced-club drills, tempo modulation), progressive overload of kinaesthetic loads, and targeted neuromuscular training informed by sEMG deficits. Continuous monitoring-using repeatable sensor placements and standardized trials-ensures that adjustments are evidence-based and that improvements in follow-through mechanics correlate with objective gains in accuracy and launch consistency.

injury prevention Considerations and Load Management in Follow Through Optimization

Optimizing the follow-through requires explicit integration of injury prevention principles grounded in contemporary sports medicine. Golf-related musculoskeletal issues commonly manifest as both acute and chronic conditions-ranging from acute strains and contusions to chronic tendinopathies and overuse syndromes-thus necessitating differential strategies for mitigation. Emphasis on tissue capacity,load variability,and controlled deceleration reduces peak joint stress during the terminal phases of the swing and is consistent with broad recommendations for sports injury management.

Effective load management relies on quantifying both external and internal load metrics and adjusting training stimulus accordingly. Practitioners should monitor a combination of objective and subjective markers:

- External: swing count, clubhead speed, range session duration

- Internal: perceived exertion, localized pain scores, regional stiffness

- Recovery: sleep quality, soreness, and inflammatory signs

these indicators permit graded progression and early detection of maladaptive responses before tissue breakdown occurs.

Technique modification during the follow-through can substantially reduce cumulative load without degrading performance. Coaching cues that promote graduated trunk deceleration, coordinated proximal-to-distal sequencing, and eccentric control of shoulder and elbow musculature attenuate impulsive joint moments. implementing targeted eccentric strengthening and neuromuscular control drills alongside technical refinement fosters resilience in the tissues responsible for deceleration.

special population considerations are essential. In adolescent golfers, open growth plates represent a biomechanically vulnerable structure that is more susceptible to overuse injury; accordingly, training loads should be conservative, with increased supervision and emphasis on cross-training and rest. For older athletes, progressive resistance training aimed at preserving muscle mass and tendon stiffness combined with mobility work can buffer against degenerative changes and decrease the likelihood of overload during repetitive follow-through motions.

Practical implementation is most effective when load decisions are operationalized into simple, reproducible rules and return-to-play criteria. The following table provides a concise progression framework usable by coaches and clinicians for session-to-session adjustments based on observed load indicators.

| Load Indicator | Recommended Action |

|---|---|

| Low soreness, normal swing count | Maintain or incrementally increase volume (≤10% per week) |

| Moderate soreness, reduced clubhead speed | Reduce sessions by 25-50%, add recovery modalities and targeted eccentrics |

| Persistent pain or functional loss | Cease high-load swings; clinical evaluation and graduated return-to-swing plan |

Q&A

1. Q: How is “biomechanics” defined in the context of a golf swing follow‑through?

A: Biomechanics is the application of mechanical principles to biological systems to understand movement and load transmission. In the context of a golf swing follow‑through, it denotes the analysis of kinematics (motion of body segments), kinetics (forces and torques), muscle actions, and the interaction with the ground and club that together determine how momentum is transferred and dissipated. (See general definitions in Britannica, Wikipedia, and biomechanics overviews cited below.)

2. Q: What are the primary biomechanical objectives of an effective follow‑through?

A: The follow‑through has three interrelated biomechanical objectives: (1) complete efficient transfer of energy from the body through the club to the ball (minimizing wasted energy),(2) controlled deceleration of the club and body to preserve shot accuracy and consistency,and (3) dissipate residual loads safely to reduce injury risk (notably in the shoulder,elbow and lumbar spine).

3. Q: What is the ideal joint‑sequencing pattern during the follow‑through?

A: An effective pattern follows a proximal‑to‑distal (inside‑out) kinematic sequence that begins with ground interaction and pelvis rotation, continues with trunk/torso rotation, then upper arm and forearm motion, and finally the wrists and clubhead. Peak angular velocities typically occur in that order with short time lags (on the order of tens of milliseconds) between successive segment peaks; maintaining that sequencing through impact and into the early follow‑through preserves clubhead speed while allowing controlled deceleration.

4. Q: How does momentum transfer operate across the kinetic chain during and after impact?

A: Momentum transfer in the swing is a coordinated redistribution of linear and angular momentum originating from the legs’ ground reaction forces and transmitted through pelvis and trunk rotation into the upper limb and club.At impact, energy is passed to the ball, and any remaining angular momentum continues through the kinematic chain into the follow‑through. Efficient transfer requires appropriate timing of torques and minimal energy losses due to early deceleration or segmental dissipation.

5. Q: What biomechanical mechanisms achieve controlled deceleration in the follow‑through?

A: Controlled deceleration is achieved through eccentric (lengthening) muscle actions and coordinated joint torques that convert kinetic energy into work within muscles, tendons and soft tissues rather than abrupt joint loading. Key contributors are eccentric control by the trunk rotators, scapular stabilizers and rotator cuff, as well as the forearm muscles that restrain wrist and club motion. Ground contact and lower‑limb mechanics (e.g., lead leg bracing) also provide a stable base to absorb residual forces.

6. Q: Which measurement modalities and metrics are most useful for studying follow‑through biomechanics?

A: Common methods include 3D motion capture for segment kinematics,force plates for ground reaction forces and center‑of‑pressure,surface EMG for muscle activation patterns,instrumented clubs or launch monitors for clubhead kinematics,and inertial measurement units (IMUs) for field measurements. Key metrics are segmental peak angular velocities and their time‑ordering (kinematic sequence), joint torques and powers, ground reaction force timing and magnitude, clubhead speed through and after impact, and EMG onset/offset and amplitude during deceleration.

7. Q: What faults in the follow‑through commonly reduce performance or increase injury risk?

A: Common biomechanical faults include: premature deceleration (reduces clubhead speed and consistency), early release/casting (loss of stored wrist/angular energy), insufficient pelvic or trunk rotation (poor energy transfer), over‑rotation or collapse of the lead leg (instability), and abrupt, poorly controlled braking using the shoulder/elbow (elevated soft‑tissue loads). Each can alter sequencing, increase joint loading, and degrade accuracy.

8. Q: How should conditioning and training be targeted to improve follow‑through mechanics and reduce injury?

A: Conditioning should address the specific demands of the follow‑through:

– Strength and power of the hips, trunk rotators, and posterior chain to generate and transfer momentum;

– Scapular stabilizers and rotator cuff strength for controlled deceleration;

– Eccentric strength training (rotational and upper‑limb) to improve braking capacity;

– Mobility of the thoracic spine and hips to permit safe ROM for sequencing;

– Neuromuscular and plyometric drills (medicine‑ball rotational throws) to improve timing and rate of force development.

Progression should be individualized and integrate load‑management principles.

9. Q: What practical coaching cues and drills translate biomechanical principles into practice?

A: Effective cues and drills include:

– “Lead with the hips” and “keep chest rotating” to reinforce pelvis→trunk sequencing;

– Finish‑hold (hold balanced full follow‑through) to train controlled deceleration and posture;

– towel‑under‑arm or impact‑bag drills to promote connected upper‑body rotation and prevent early release;

– Medicine‑ball rotational throws to train coordinated proximal‑to‑distal force production and deceleration;

– Slow‑motion to full‑speed progression and video feedback to correct timing. Pair drills with physical screening to target athlete limitations.

10. Q: How should follow‑through strategies be individualized?

A: Individualization considers player anthropometrics,physical capabilities (strength,mobility,previous injuries),swing style,and shot requirements. Assessment should include movement screens (thoracic rotation, hip internal/external rotation), strength tests (rotational power, eccentric control), and on‑swing analysis. Modifications may include altered sequencing emphasis, reduced maximal rotation, or technical substitutions (e.g., longer/shorter follow‑through) to accommodate limitations while preserving energy transfer efficiency.

11. Q: What are the principal injury mechanisms linked to poor follow‑through,and how can they be mitigated?

A: Injury mechanisms include repetitive eccentric overload of the rotator cuff and elbow flexors/extensors,torsional/shear loading of the lumbar spine from abrupt trunk deceleration,and overuse of scapular musculature from poor scapulothoracic control.Mitigation strategies are eccentric strengthening, progressive load exposure, restoration of mobility (thoracic, hips), motor control training for scapular timing, and technical adjustments to reduce peak harmful torques.

12. Q: What are the current limitations of the biomechanical literature on follow‑through and priority areas for future research?

A: Limitations include a predominance of cross‑sectional lab studies with small samples, limited ecological validity (on‑course variability and fatigue effects are under‑studied), and relatively few longitudinal or intervention trials linking specific follow‑through modifications to long‑term performance and injury outcomes. Priorities include wearable sensor validation for on‑course monitoring, subject‑specific musculoskeletal modeling to estimate internal loads, fatigue and volume effects across practice/competition, and randomized trials of targeted training interventions.

13. Q: How can researchers and clinicians translate biomechanical findings to everyday coaching and athlete care?

A: translation requires multidisciplinary collaboration: combine objective assessment (motion/force/EMG or wearable data) with clinical movement screens, interpret metrics relative to the athlete’s goals and constraints, prescribe targeted physical interventions (strength, mobility, motor control), and use iterative testing and feedback (video/IMU/launch monitor) to evaluate effects. Emphasize simple, reproducible drills that reinforce correct sequencing and controlled deceleration while monitoring for pain or adverse responses.

14. Q: Concisely, what are the take‑home biomechanical recommendations for improving follow‑through?

A: reinforce a proximal‑to‑distal kinematic sequence; generate momentum from the lower body and trunk; allow the body to carry momentum through impact into a balanced follow‑through; train eccentric deceleration capacity in the trunk and shoulder; screen and address mobility or strength deficits that compromise sequencing; and use objective measures (video, launch monitor, IMUs) to monitor timing and control while accounting for individual constraints.

references and further reading (selected general sources):

– Britannica: Biomechanics overview.

– Wikipedia: Biomechanics.

– The Biomechanist: What is Biomechanics?

(See the provided links for general definitions and introductory material on biomechanics.)

If you would like, I can: (a) convert these Q&As into a printable FAQ for coaches, (b) add sample measurement protocols (marker sets, force plate metrics, EMG placement), or (c) produce a short drill progression tailored to a given player profile.

To Wrap It Up

a biomechanically informed approach to the golf swing follow-through-one that emphasizes coordinated joint sequencing, efficient momentum transfer, and controlled deceleration-offers a coherent framework for improving shot accuracy, consistency, and musculoskeletal safety. Grounded in the broader discipline of biomechanics, which applies mechanical principles to understand human movement and function, this perspective elucidates how proximal-to-distal sequencing, timed energy dissipation, and joint-specific load management collectively shape post-impact outcomes.

For practitioners and researchers, the practical implications are clear: coaching interventions should prioritize reproducible kinematic patterns and scalable drills that reinforce desirable sequencing and deceleration strategies, while clinicians should incorporate objective movement assessment and load-monitoring to mitigate injury risk. Methodologically, future studies will benefit from integrating high-fidelity motion capture, wearable inertial sensors, and musculoskeletal modeling to quantify intersegmental dynamics across diverse player populations and playing conditions. Attention to individual anatomical variation, training history, and equipment interactions will be essential for translating group-level biomechanical insights into personalized prescriptions.

Ultimately,advancing performance and reducing injury in golf requires sustained collaboration between biomechanists,coaches,clinicians,and athletes. by uniting rigorous measurement with applied training paradigms, the field can continue to refine evidence-based follow-through strategies that respect both the mechanical principles of human movement and the practical demands of play.

Biomechanical Strategies for Golf Swing Follow-Through

Why the follow-through matters for clubhead speed and shot accuracy

The follow-through is frequently enough treated as the aesthetic finish of the golf swing, but biomechanically it is indeed a critical phase that reflects the efficiency of energy transfer from body to club to ball. A well-executed follow-through helps ensure:

- maximum clubhead speed through coordinated trunk rotation and arm extension.

- Consistent impact position and clubface alignment to improve shot accuracy and reduce dispersion.

- Optimal launch angle and spin characteristics by encouraging the correct release and wrist pronation.

- Injury prevention through safe deceleration patterns and balanced weight transfer.

core biomechanical principles of an effective follow-through

Understanding basic biomechanics helps golfers and coaches refine the follow-through with purpose rather than guesswork. These principles are grounded in how muscles, joints, and segments interact during motion.

1. Sequential segmental rotation (kinetic linking)

The golf swing is a kinetic chain where energy is generated from the ground up: legs → hips → trunk → shoulders → arms → wrists → club. Efficient trunk rotation during and after impact ensures energy flows smoothly. A stalled or early-decelerated trunk disrupts this sequence and reduces clubhead speed.

2. Controlled arm extension and release

Post-impact arm extension allows the club to continue on the designed swing arc, promoting a square clubface through impact. Over-shortening or abrupt stopping of the lead arm post-impact alters the club path and launch conditions.

3. Forearm pronation and wrist mechanics

Wrist pronation (the natural rotation of the forearms) through impact helps square the clubface and affect spin. A smooth, timed pronation prevents flicking or casting, improving ball flight consistency.

4. Balance,centre of mass,and ground reaction forces

Ground reaction forces (GRF) contribute to power. Proper weight transfer to the lead side during follow-through stabilizes the body and allows post-impact rotation to continue, enhancing accuracy and repeatability.

Follow-through checkpoints: what to look for on the range

| Checkpoint | Why it matters | Speedy drill |

|---|---|---|

| Full chest rotation to target | Indicates efficient trunk rotation & energy transfer | Slow-motion half-swings, pause at finish |

| Lead arm extended, but relaxed | Keeps club on arc and stabilizes flight | Towel-under-arms drill |

| Hands finish around shoulder height | Balanced release and reduced spin variability | Finish-hold practice swings |

| weight on lead foot, slight toe raise | Shows proper weight transfer and balance | Toe-tap balance drill |

Common follow-through faults and biomechanical corrections

Below are frequent problems with suggested biomechanical fixes and practice cues.

- Early body finish (spinning out): Result of over-rotating or collapsing to the trail side. correction: focus on stabilizing the lower body and allow controlled trunk rotation; practice maintaining spine angle through impact.

- hands flip or cast (early release): Caused by poor wrist timing or weak forearm control. Correction: strengthen wrist and forearm, use release drills (hold impact position, let club swing through naturally).

- Short finish / lack of extension: Short finish often means energy was decelerated early. Correction: drill with longer swings and exaggerate full finish to ingrain extension.

- Open/closed clubface at finish: Indicates poor pronation timing or incorrect path. Correction: use slow-motion swings and video to check forearm rotation through impact.

Practical drills to optimize trunk rotation, arm extension, and wrist pronation

these drills are simple, reproducible, and designed to be used on the range or at home. Frequency: 2-4 sets of 8-12 reps per drill, 3-4 times per week for skill conditioning.

1. Finish-Frame Drill

Objective: reinforce full chest rotation and balanced finish.

- Take 3⁄4 swings and hold the finish for 2-3 seconds.

- Check that chest faces the target,lead arm extended,and weight on lead foot.

- Use mirror or video to confirm alignment.

2. Towel-Under-arms Drill

Objective: maintain connection between torso and arms and prevent chicken-winging.

- Tuck a small towel under both armpits and swing. The towel should stay in place through the follow-through.

- Promotes integrated torso-arm synergy and natural extension.

3. Forearm Pronation Drill (Impact Tape)

Objective: train correct pronation timing.

- Use a short iron and make half-swings focusing on rotating the lead forearm through impact.

- Optional: place a small piece of cloth or impact tape on the clubface to feel square contact.

4.Toe-Tap Balance Drill

Objective: practice weight transfer and balanced finish.

- After impact, lightly tap the lead toe to make sure weight is shifted forward and held through follow-through.

- Improves GRF utilization and stability.

Golf fitness: mobility and strength for a safe, powerful follow-through

Biomechanics depends on the athlete’s physical capacity. Combine mobility work, strength training, and endurance for a reliable follow-through.

Key areas to train

- Thoracic spine mobility: Enables full trunk rotation without compensating with the lower back.

- Hip strength and rotational power: Drives the pelvis through impact and into follow-through.

- Core stability: Controls sequencing and resists unwanted lateral flexion.

- Forearm and wrist strength: Improves release control and pronation timing.

Sample mini-program (2× week)

- Dynamic thoracic rotations: 2 sets × 10 reps each side

- Rotational medicine-ball throws: 3 sets × 8 reps

- Single-leg deadlifts: 3 sets × 8-10 reps per leg

- Farmer carries for grip: 3 × 30-45 seconds

How to use technology to measure follow-through improvements

Modern tools provide objective feedback so biomechanical changes translate to measurable performance gains.

- Launch monitors: track clubhead speed, launch angle, spin rate, and dispersion to quantify changes after technique tweaks.

- High-speed video or 240+ fps cameras: Analyze timing of trunk rotation, arm extension, and wrist pronation frame-by-frame.

- Wearable IMUs and force plates: Provide data on rotational velocity, GRF, and weight transfer patterns.

Mini case study: transferring follow-through changes to the course

Illustrative example: an amateur golfer struggled with a rightward miss and low launch. coach focused on three biomechanical cues-full trunk rotation through impact, delayed pronation, and sustained lead-arm extension-and used these steps:

- Baseline video and launch monitor readings to record clubhead speed and dispersion.

- Three weeks of the Finish-Frame Drill, Towel-Under-Arms, and thoracic mobility work (6 sessions total).

- Retest with video and launch monitor.

Result (illustrative): the student reported better feel, video showed improved chest rotation and a later pronation, and dispersion narrowed on the range. This demonstrates how small biomechanical adjustments in the follow-through can yield meaningful improvements in shot accuracy.

Practical practice plan: 6-week follow-through refinement

Use this weekly framework to build habits and monitor progress.

- Weeks 1-2: Technique awareness – slow swings, drills (Finish-Frame, Towel-under-Arms), mobility work.

- Weeks 3-4: Integration – add controlled full swings with impact checks, video analysis once per week.

- Weeks 5-6: Performance transfer – use launch monitor sessions and play 9 holes focusing on maintaining new follow-through cues under course pressure.

Coach and player cues that work

- “Finish tall and balanced” – promotes posture and weight transfer.

- “Extend the lead arm, don’t stop it” – encourages continuation through impact.

- “Rotate the chest to the target” – aligns trunk rotation sequencing.

- “Rotate the forearms naturally” – discourages flicking with the wrists.

Quick takeaway: The follow-through is a reflection of your swing mechanics. Prioritize coordinated trunk rotation, smooth arm extension, and timed wrist pronation to improve clubhead speed, launch conditions, and shot accuracy.

Resources and next steps

To continue improving your follow-through:

- Record slow-motion swings and compare before/after footage.

- Work with a coach who integrates biomechanical feedback and technology.

- Pair technique work with a golf-specific fitness routine focused on rotation and stability.

Suggested reading & references

- General biomechanics overview: Verywell Fit – Understanding Biomechanics & Body Movement

- Foundational biomechanics concepts: The Biomechanist – What is biomechanics?

- Introductory review: Biomechanics (Wikipedia / PMC articles) for context about movement science.