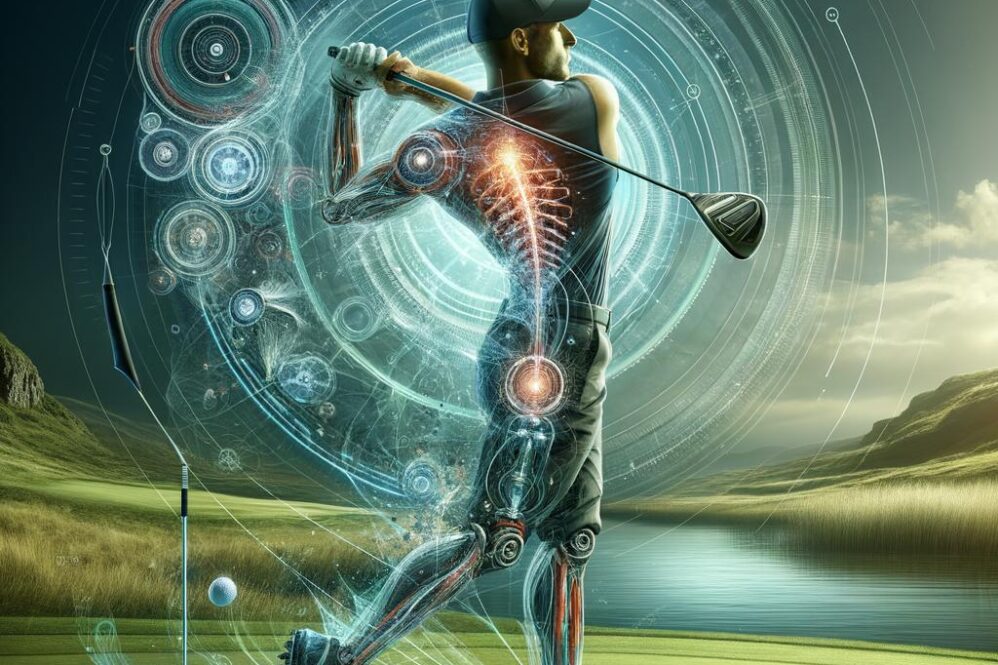

Optimizing golf performance requires a synthesis of biomechanical understanding and targeted conditioning strategies that translate scientific insight into practical training and injury-mitigation protocols. biomechanics-defined broadly as the application of mechanical principles too living systems-provides a framework for quantifying how forces, motions, and musculoskeletal structures interact during the golf swing and related movements (Britannica; Nature).When coupled with contemporary measurement technologies and interdisciplinary methods developed in biomechanics research, these analyses yield objective markers of movement efficiency, intersegmental coordination, and load distribution that are directly relevant to shot consistency and power generation (Stanford Biomechanics; MIT).

Contemporary biomechanical assessment in golf employs kinematic and kinetic analyses,electromyography,and force-platform data to characterize swing patterns,identify compensatory strategies,and detect asymmetries that predispose athletes to injury. Integrating these data with conditioning science-encompassing neuromuscular training, mobility and stability programming, and energy-system conditioning-enables practitioners to design individualized interventions that address the underlying mechanical and physiological contributors to performance deficits. This multidisciplinary approach, increasingly emphasized in academic and applied settings, leverages collaboration among biomechanists, strength and conditioning specialists, physiotherapists, and sport scientists to translate laboratory findings into field-ready training prescriptions (Stanford Biomechanics; MIT).

the practical outcome of an integrated biomechanical-conditioning paradigm is twofold: enhanced movement economy and reproducibility of swing mechanics, and a reduced incidence of overload injuries through targeted corrective and load-management strategies.By aligning diagnostic biomechanical markers with periodized conditioning objectives-ranging from reactive strength and rotational power to motor-control refinement and metabolic resilience-coaches and clinicians can create evidence-based pathways that improve performance while safeguarding athlete health. Continued research at the interface of biomechanics and conditioning will refine these methods, enabling more precise, sport-specific interventions that elevate both elite and recreational golfers.

biomechanical Principles Underpinning the Golf Swing with Practical Implications for Coaching and Measurement

Contemporary analysis situates the golf swing within the domains of both kinematics and kinetics: linear and angular velocities, segmental accelerations, and internal/external moments determine ball launch conditions as much as technique. Key mechanical constructs include angular momentum of the trunk and club, the timing of peak segmental angular velocities, and the generation and transfer of force through the ground. Equally crucial are tissue-level responses such as stretch-shortening cycle utilization in the hips and torso and the capacity to tolerate transverse shear in the lumbar spine; these influence both performance ceilings and injury risk profiles.

Efficient motion is characterized by well-timed proximal-to-distal sequencing and appropriate intersegmental separation between pelvis and thorax (the classical “X‑factor”), producing high clubhead speed with minimal compensatory motion. Stability of the lower extremity and lumbopelvic complex provides a platform for rotational power, while adequate thoracic mobility and scapular control permit energy transfer without excessive stress.Coaches should therefore distinguish between deficiencies in mobility, strength, motor control, and timing when diagnosing swing faults, since similar external deviations (e.g., early extension) may arise from disparate biomechanical origins.

From a practical coaching standpoint, emphasis should be placed on objective metrics and targeted interventions that translate mechanical understanding into easily communicated cues. Useful measurement modalities include 3D motion capture for kinematic sequencing, inertial measurement units (IMUs) for field-based angular velocity profiles, force platforms for ground reaction force analysis, and launch monitors for resultant ball/clubhead outcomes. Typical assessment and intervention elements include:

- Assess: pelvis-shoulder separation, peak trunk angular velocity, weight transfer symmetry.

- Measure: ground-reaction-force timing, clubhead speed, swing tempo ratios.

- Intervene: mobility progressions, strength/power conditioning, coordination drills emphasizing timing (e.g., medicine‑ball rotational throws), and real-time biofeedback.

These elements support a data-driven feedback loop that aligns technical instruction with measurable physiological capacity.

For practical implementation, a concise measurement-to-intervention matrix clarifies priorities for both on-course coaching and conditioning plans.

| Metric | Tool | Target/Interpretation | Intervention |

|---|---|---|---|

| Clubhead speed | Launch monitor | Individualized % above baseline | Power training + sequencing drills |

| Pelvis rotation ROM | Goniometer/IMU | Symmetric ≥30° | Thoracic mobility & hip internal rotation work |

| Peak GRF timing | Force plate | Weight transfer by mid-downswing | Balance & explosive drive drills |

| Swing tempo (ratio) | Video/IMU | ~3:1 (backswing:downswing) | Metronome-led swing repetitions |

Adopting this framework enables coaches to prioritize interventions that are both biomechanically principled and measurable, thereby improving transfer from practice to performance while monitoring tissue loading and adaptation.

Assessing mobility and Stability of the Hips Spine and Shoulders to Correct Swing Faults and Enhance Power transfer

Objective measurement of joint range, segmental stability, and neuromuscular control is essential to identify the mechanical constraints that degrade rotary power and increase injury risk. Standardized tools-handheld goniometer, digital inclinometer, pressure-sensing force plates and inertial measurement units (IMUs)-provide repeatable metrics for the hips, thoracic spine and shoulder complex. In addition to isolated ROM values, evaluate dynamic control with single‑leg balance tests, resisted rotation tasks and timed transitional movements (e.g., step‑onset to full rotation). Collecting both static and dynamic data allows clinicians to distinguish between a mobility limitation (restricted passive ROM) and a stability/control deficit (inability to use available ROM under load).

Biomechanical consequences of common deficits are predictable and clinically actionable. For example:

- Reduced hip internal rotation → increased lateral sway and early extension (reverse spine angle) during downswing.

- Limited thoracic rotation → compensatory increased lumbar rotation or early arm casting, reducing stored elastic energy.

- Poor scapular stability → inconsistent clubface orientation and loss of distal power transmission.

- Inadequate pelvic control → delayed weight shift, blunted hip drive and reduced peak clubhead speed.

| Test | Threshold / Clinical Flag |

|---|---|

| Passive Hip IR (90° hip flexion) | < 20° suggests restriction |

| Seated Thoracic Rotation | < 45° indicates limited trunk dissociation |

| Shoulder ER at 90° Abduction | < 60° may impair takeaway and follow‑through |

Intervention should follow a hierarchical, evidence‑based progression: address soft tissue and joint restrictions first, then restore motor control, then increase capacity and integrate into sport‑specific patterns. Typical corrective elements include:

- mobility: hip joint mobilizations, thoracic extension/rotation mobilities, posterior shoulder capsule stretches.

- activation / Stability: prone and side‑plank progressions, gluteal bridging with single‑leg hold, scapular clocking and banded wall slides.

- Strength & Power Integration: loaded hip hinge and single‑leg Romanian deadlifts, rotational medicine‑ball throws and resisted cable chops timed to swing phases.

Progression should be criterion‑based (not time‑based): only advance when the athlete demonstrates controlled use of increased ROM under task‑specific loads, and validate transfer by reassessing the original swing fault using on‑course or simulated swing metrics (clubhead speed, pelvis‑thorax separation, and movement symmetry).

Developing Rotational Strength and Rate of Force Development to Improve Clubhead speed and Shot Consistency

Rotational motion-conceptualized in physics as the circular movement of a body around an axis (see Merriam‑Webster; Wikipedia)-provides a useful framework for understanding the golf swing. From a biomechanical perspective, effective shot production depends on coordinated rotational kinematics and kinetics: a sequenced transfer of energy from the ground, through the hips and torso, into the shoulders and hands. this **proximal‑to‑distal sequencing** maximizes clubhead velocity while minimizing compensatory stresses on passive tissues. Quantifying rotation in terms of angular velocity, range of motion, and timing clarifies how deficits in any link of the kinetic chain reduce both speed and consistency.

The conditioning focus should therefore be twofold: increase maximal rotational strength and improve rate of force development (RFD) in transverse plane actions so force is produced rapidly within the short timespan of the downswing. RFD characterizes how quickly torque or force increases (i.e., the slope of the force‑time curve) and is a stronger determinant of dynamic performance than maximal strength alone in time‑constrained tasks. The table below summarizes representative drills, thier primary training objective, and simple loading/tempo prescriptions appropriate for on‑course transfer.

| Drill | primary Target | Load / Tempo |

|---|---|---|

| Explosive med‑ball rotational throw | RFD, hip‑torque transfer | 1-3 kg; max intent; 3-5 reps |

| Cable woodchop (high→low) | Rotational strength & sequencing | Moderate load; 6-8 reps; controlled return |

| Standing rotational deadlift | Posterior chain + anti‑flexion | Heavy; 3-5 reps; slow eccentric |

| Anti‑rotation Pallof press | Core stiffness & transfer | Light‑moderate; 8-12 reps each side |

Exercise selection and progression should emphasize velocity specificity, joint integrity, and motor control. Begin with movement quality and anti‑rotation stability, progress to loaded strength, and finally prioritize high‑velocity, low‑load power work that replicates the time constraints of the swing. Recommended implementation includes:

- Stability phase: pallof presses, deadbugs, hip mobility (2-3 sessions/week)

- Strength phase: unilateral hip hinge, weighted cable chops, heavy rotational deadlifts (2 sessions/week)

- Power phase: med‑ball throws, overspeed swings, band‑resisted rotations (2 sessions/week; maximal intent)

Emphasize technical fidelity-maintaining torso stiffness while allowing efficient hip rotation-so gains in the weight room transfer to on‑course performance.

Assessment and monitoring are essential to ensure transfer and injury prevention. Use practical field tests (e.g., seated or standing medicine‑ball rotational throw distance, clubhead speed via radar, smash factor) alongside laboratory metrics when available (force‑plate RFD, isokinetic rotation torque). Track progress with short, objective tests and adjust periodization according to competitive calendar and fatigue markers. integrate conditioning with swing work: brief maximal intent power sessions placed before technical practice enhance neuromuscular readiness, whereas high‑volume strength work is best programmed away from competition to preserve swing timing and consistency.

neuromuscular Coordination and Motor Control Training Strategies to Optimize Sequence Timing and Reduce Compensatory patterns

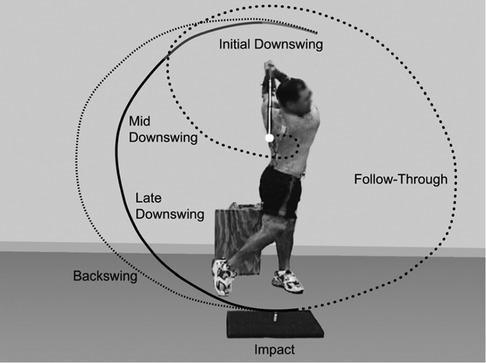

Sequenced intersegmental coordination underpins efficient energy transfer in the golf swing; optimal performance arises when pelvic rotation, thoracic counter-rotation, and upper-limb acceleration occur with precisely timed phase transitions. Deviations in timing-early arm pull, delayed pelvis rotation, or prolonged lead knee extension-produce compensatory patterns that increase variability in launch conditions and raise injury risk.Quantifying temporal relationships (e.g., pelvis-to-shoulder peak velocity lag, upper-limb peak angular velocity) provides objective targets for intervention and the basis for evidence-informed conditioning strategies.

Assessment should couple biomechanical analysis with neuromuscular evaluation to reveal whether poor sequencing is motor-control driven or secondary to strength/endurance deficits. Clinical neuromuscular tools (qualitative movement screens, reactive balance tests, and, where available, surface electromyography or markerless kinematics) identify abnormal activation onset, asymmetries, and co-contraction patterns. This diagnostic layer enables targeted prescription: re-education of timing and selective strengthening rather than indiscriminate volume work that may entrench maladaptive patterns.

Training integrates motor learning principles with progressive overload: brief,high-fidelity exposures to the desired temporal pattern,distributed practice to consolidate timing,and variability to generalize robustness under perturbation. Use of external focus cues (e.g., “transfer energy through the lead hip to the clubhead”), augmented feedback (video with temporal overlays, auditory metronomes keyed to phase transitions), and task constraints (reduced backswing, resisted lead-hip drive) systematically shape motor programs. concurrently, condition drills emphasize rate of force development and intermuscular coordination of the posterior chain and rotator cuff to support rapid, well-sequenced motion while minimizing compensatory recruitment.

Practical drills and progression combine specificity and measurability:

- paused-sequence swings with emphasis on pelvic initiation (3-5 sets of 6-8 reps)

- reactive step-to-swing drills with perturbation (2-3 sets of 10 reps)

- Auditory-timed acceleration drills using metronome phases (4-6 sets of 4 reps)

Monitor progress using simple metrics (clubhead speed, pelvis-to-shoulder timing, perceived effort) and adjust load or constraint complexity. Below is a concise progression table for practitioner use.

| Drill | Primary Target | Progression |

|---|---|---|

| Paused Pelvic Initiation | Pelvis→thorax timing | Increase speed, reduce pause |

| Perturbation Step-to-Swing | Reactive sequencing | Increase perturbation magnitude |

| Metronome Acceleration | Phase timing consistency | Shorten tempo interval |

Energy System Conditioning and Periodization Models to Sustain Performance Across Practice and Competition

Optimizing the physiological engines that underpin golf performance requires targeted development of the ATP-PC (phosphagen), glycolytic (anaerobic), and oxidative (aerobic) systems to reflect the sport’s intermittent, high-power demands interspersed with prolonged low-intensity activity. Practically, this means prioritizing short-duration, maximal-output efforts to increase clubhead speed and neuromuscular power while concurrently building lactate tolerance for repeated intense swings and an aerobic base to expedite recovery between shots and rounds. Integrating energetics with biomechanical efficiency reduces wasted work and preserves movement quality under fatigue, thereby sustaining shot consistency across multi-day competition.

Periodization must thus be system-specific and schedule-aware: macrocycles should align with the competitive calendar, mesocycles allocate emphases on power, capacity, and recovery, and microcycles manipulate intensity and density to elicit desired adaptations without disrupting technical motor learning. Models such as undulating periodization (frequent shifts in focus) are often preferable to rigid linear approaches for golfers because they better mirror tournament variability and technical practice needs. This systems-oriented approach shares conceptual parallels with contemporary energy research that emphasizes optimization, scaling, and resilience (see institutional work on energy ventures and materials testing), reinforcing the value of a purposeful, evidence-based architecture for conditioning plans.

Session design must be explicit and measurable. Core session types include:

- Power/Speed (short, high intensity) – 6-12 s efforts, long recoveries (1:12-1:20 work:rest), focus on explosive rotational output and rate of force development.

- Speed-Endurance (repeated high outputs) – 15-45 s intervals, moderate rest (1:4-1:6), emphasizing swing repetition under metabolic stress while preserving technique.

- Aerobic Recovery & Base (low intensity) – 20-60+ minutes at conversational intensity, to accelerate phosphagen and lactate recovery between bouts and improve thermoregulatory resilience.

- Regeneration/Neuromotor – low-load mobility and coordination work on competition days to maintain movement quality without inducing fatigue.

Prescribe load using objective markers (RPE, heart rate variability, or power meters) and tie them to technical outcomes measured in practice.

Translate periodization into a concise weekly blueprint to help coaches and players operationalize energy-system priorities. The table below offers a simple, adaptable template linking phase, primary energy focus, and typical weekly emphasis that can be scaled for amateur through elite timelines.

| Phase | Primary Energy Focus | Weekly Emphasis |

|---|---|---|

| Preparatory | Aerobic base + strength/power foundation | 2 power, 1 speed-endurance, 2 aerobic, 2 technical |

| Competitive | Power maintenance + tactical speed-endurance | 1-2 power, 1 speed-endurance, 1 aerobic, increased recovery |

| Transition/Recovery | Regeneration and neuromotor retraining | Low volume mixed activity, mobility, technique refresh |

Injury Risk Identification and Preventive Conditioning Protocols targeting Common Golf Pathologies

Risk identification relies on a structured clinical and biomechanical appraisal that combines athlete history, symptom mapping, and objective movement analysis. Key red flags include asymmetrical hip rotation, altered pelvis-trunk timing (kinematic sequencing deficits), and repeated high-velocity wrist/elbow loading.Screening tools should include:

- instrumented range-of-motion and force-testing where available;

- functional movement screens emphasizing rotation, hinge, and single-leg stability;

- quantified workload monitoring and pain-progression logs to detect overuse patterns-especially in youth athletes susceptible to growth-plate stress.

These practices align with established sports-injury frameworks that identify tissue-specific risk factors and mechanisms for prevention.

Spine and lower‑extremity protocols prioritize restoration of hip mobility, lumbopelvic control, and posterior‑chain capacity to redistribute forces away from the lumbar spine during the swing. Evidence-based components include progressive hip internal‑rotation drills, multi‑plane gluteal strengthening, eccentric hamstring work, and graded rotational power training.Conditioning progressions should emphasize motor control (slow, precise patterns) before introducing high‑velocity, golf‑specific loading; planned deload periods and objective pain thresholds must guide intensity to reduce recurrence risk.

Upper‑extremity and wrist interventions focus on scapular stabilizers, rotator cuff endurance, and tendon‑specific loading to mitigate rotator cuff tendinopathy, medial epicondylalgia, and compressive neuropathies. Recommended elements are:

- scapulo‑thoracic rhythm retraining and low‑load rotator cuff endurance sets;

- eccentric forearm protocols for tendon remodeling;

- nerve‑mobilization and carpal alignment drills where symptoms suggest median nerve irritation.

Progression to high‑speed drills must follow objective strength and neuromuscular milestones to preserve kinetic‑chain sequencing and limit compensatory loads at the wrist and elbow.

| Pathology | Primary biomechanical risk | Preventive conditioning |

|---|---|---|

| lumbar overload / LBP | Poor hip rotation / early trunk extension | hip mobility,core endurance,posterior chain strength |

| Medial epicondylalgia | Repetitive high wrist flexion/force | Eccentric forearm loading,load management |

| Rotator cuff tendinopathy | Scapular dyskinesis / poor deceleration | Scapular control,rotator cuff endurance,gradual plyometrics |

| Growth‑plate stress (youth) | Excessive cumulative load / early specialization | Age‑appropriate load limits,cross‑training,monitoring per growth‑plate guidance |

return‑to‑play criteria should be criterion‑based (strength symmetry,pain‑free sport‑specific execution,and validated movement quality metrics) and incorporate conservative timelines for skeletally immature athletes as described in pediatric sports‑injury guidance.

Integrative Testing Monitoring and Program Design to Translate Biomechanical Insights into Individualized Training Interventions

clinically-oriented practitioners translate biomechanical diagnostics into individualized conditioning plans by establishing a systematic, evidence-informed framework that links assessment findings with mechanistic interventions. This framework prioritizes **movement quality**, kinetic sequencing, and neuromuscular control as primary drivers of on-course performance, while concurrently accounting for musculoskeletal load capacity and athlete-specific constraints (injury history, training age). Baseline characterization therefore includes both laboratory-grade biomechanical outputs and field-usable proxies so that prescription is both mechanistically precise and practically implementable.

Monitoring is organized across convergent data streams to capture the athlete’s state and response to load: objective biomechanical metrics, physiological load markers, and subjective recovery indices. typical elements include:

- Biomechanical tools: 3D kinematics, force-plate-derived ground reaction forces, IMU-derived club and trunk sequencing.

- Physiological markers: HRV, submaximal lactate/ RPE relationships, and sprint/power decay tests.

- Subjective/recovery metrics: wellness questionnaires, pain-scales, and sleep quality.

These streams are weighted according to validity, reliability, and feasibility for the golfer, and integrated into a longitudinal dashboard that flags meaningful change beyond measurement error.

Translational program design operationalizes assessment-to-intervention mappings so that each session targets a quantifiable deficit. The following exemplar schema demonstrates this mapping and supports periodized sequencing from remediation to performance optimization:

| Assessment | Primary Deficit | Targeted Intervention |

|---|---|---|

| Pelvic-shoulder sequencing lag (IMU) | Timing and power transfer | Segmental sequencing drills + rotational plyometrics |

| Reduced hip internal rotation | Mobility limiting swing arc | Soft-tissue work + loaded end-range mobility |

| Declining peak clubhead speed under fatigue | Anaerobic power/endurance | High-intensity tempo training + metabolic conditioning |

Effective translation requires an iterative evaluation loop led by an **interdisciplinary team** (coach, biomechanist, strength coach, clinician) and guided by predefined progression criteria and return-to-performance metrics. Protocols specify when to advance from corrective work to power development and how to taper neuromuscular load before competition. complementary integrative strategies-structured recovery, nutrition periodization, and mental skills training-are incorporated where evidence supports benefit, reflecting a whole-person approach to sustain adaptation and reduce injury risk. Continuous reassessment closes the loop: interventions are retained, modified, or retired based on objective improvement, athlete-reported outcomes, and competition readiness.

Q&A

Below is a professional, academic-style question-and-answer compendium intended to accompany an article on “Biomechanics and Conditioning for Golf Performance.” The Q&A synthesizes core biomechanical principles, assessment methods, conditioning strategies, injury-prevention considerations, and translational issues relevant to players, coaches, and sport scientists.Where appropriate, general biomechanical background is referenced to the provided literature on biomechanics as a scientific discipline.

1. what is meant by “biomechanics” in the context of golf performance?

Answer: Biomechanics applies the principles of mechanics to living systems to quantify how forces, motion, and structural properties produce movement. In golf, biomechanics focuses on kinematics (motion of body and club), kinetics (forces and moments), neuromuscular coordination (timing and sequencing), and tissue loading during the golf swing and related movements. As an interdisciplinary field, biomechanics integrates engineering, physiology, anatomy, and motor control to improve performance and reduce injury risk [2][3][4].

2. Why integrate biomechanics with conditioning for golf?

Answer: Integrating biomechanical analysis with targeted conditioning aligns a golfer’s physical capacities (strength, mobility, power, endurance, motor control) with the mechanical demands of the swing. this integration improves movement efficiency, enhances neuromuscular coordination, increases shot consistency and power, and mitigates injury risk by addressing tissue load tolerance and movement deficits.Conditioning without biomechanical alignment risks training non-transferable qualities; biomechanical analysis without conditioning limits a player’s ability to realise optimal mechanics.

3.What are the primary biomechanical targets to assess for golf performance?

answer: Key targets include:

– Kinematics: pelvis and thorax rotation, shoulder turn, wrist mechanics, hip and knee angles, sequencing (proximal-to-distal).

– Kinetics: ground reaction forces, joint moments (particularly hip and lumbar), and torque generation about the torso.

– Temporal sequencing: peak rotational velocities and timing of pelvis, trunk, arms, and club.

– Club and ball metrics: clubhead speed, ball speed, launch angle, spin rate, and smash factor.

– Movement variability and repeatability across swings.

4. Which measurements and tools are useful for biomechanical assessment?

Answer: Common tools include 3D motion-capture systems (gold standard for kinematics), high-speed video, force plates (ground reaction forces and weight transfer), electromyography (muscle activation timing and amplitude), inertial measurement units (IMUs) for field-based monitoring, and launch monitors for ball/club metrics. Selection depends on resources and the question being asked; portable tools (IMUs, high-speed video, launch monitors) can offer practical insight when laboratory equipment is unavailable [2][3].

5. What are consistent biomechanical markers associated with effective and safe swings?

Answer: effective swings typically show:

– Efficient proximal-to-distal sequencing (pelvis → trunk → arms → club).

– Adequate separation between pelvic and thoracic rotation (“X‑factor”) without excessive compensatory lumbar motion.

– Rapid but well-timed transfer of ground reaction forces and weight shift.

– Controlled deceleration through the upper body and scapulothoracic region.

Safety markers include balanced loading of lower limbs, limited excessive lumbar shear/extension at high velocities, and symmetrical or appropriately biased joint loading based on the player’s swing style.

6. How do mobility and stability contribute to an optimal swing?

Answer: Mobility provides necessary ranges of motion (thoracic rotation, hip internal/external rotation, ankle dorsiflexion) that permit desirable swing positions. Stability (lumbopelvic control, scapular stability, single-leg control) ensures those ranges are used in a controlled way that preserves sequencing and reduces compensatory movements. Mobility without stability can increase injury risk; stability without mobility can constrain technique.

7. Which physical qualities should conditioning prioritize for golfers?

Answer: prioritized qualities:

– Rotational power and speed (specific to swing velocity).

– Hip and posterior-chain strength (force generation and transfer).

– Core anti-rotation and lumbopelvic control (force transfer and spine protection).

– Thoracic mobility and scapular control (proximal motion for shoulder function).

– Single-leg strength and balance (weight transfer and stability).

– Local muscular endurance for prolonged practice/competition and recovery capacity across a round.

8. What exercise modalities most effectively transfer to golf performance?

Answer: Exercises that emphasize force production in rotational or multiplanar contexts transfer best. Examples: medicine-ball rotational throws, band- or cable-resisted chops and lifts, kettlebell swings, Romanian deadlifts, hip-dominant lifts (deadlifts, hip thrusts), single-leg squats and RDLs, anti-rotation Pallof presses, and high-velocity plyometric or ballistic movements executed with golf‑specific postures.Strength training builds a force capacity that power work can convert into high-velocity outputs.9. How should a conditioning program for golfers be structured (general periodization and weekly template)?

Answer: General approach:

– Off-season: emphasize foundational strength (hypertrophy/strength 2-4 months), mobility deficits correction, and progressive power work.

– Pre-season: transition to higher velocity, power, and sport-specific conditioning; integrate swing-specific drills with loaded plyometrics.

– In-season: maintain strength and power with lower volume, focus on recovery, on-course conditioning, and session timing relative to play.

Weekly microcycle (example): 2-3 strength sessions (heavy/moderate loads), 1-2 power-specific sessions (medicine ball throws, plyometrics), daily mobility and activation work, and conditioned cardiovascular work as needed for overall work capacity. Monitor fatigue and adjust.

10. what are practical rep/load/intensity guidelines for golf conditioning?

Answer: Practical ranges:

– Maximal strength: 2-6 reps, 3-6 sets, heavy loads (≥85% 1RM) to raise force capacity.

– Hypertrophy/strength endurance: 6-12 reps, moderate loads.

– Power: 1-6 reps, high velocity, 3-6 sets, moderate loads or ballistic (bodyweight/med-ball) emphasizing intent and technique.

– Local muscular endurance: 12-20+ reps or time-under-tension for conditioning specific stabilizers.

Integrate power after strength sessions or on separate days to maximize neuromuscular quality.11. How does neuromuscular sequencing (kinematic sequence) affect performance?

Answer: the kinematic sequence-timing of peak angular velocities from the pelvis through trunk to club-affects how efficiently kinetic energy is transferred to the club. An optimal proximal-to-distal sequence maximizes clubhead speed while minimizing compensatory movements that can degrade accuracy or increase joint stress.Conditioning that enhances rotational strength,timing,and rate of force development supports optimal sequencing.

12. Which injuries are most common in golfers and how can conditioning mitigate them?

Answer: Common injuries: low back pain, medial epicondylitis (golfer’s elbow), shoulder impingement/rotator cuff pathology, and knee/hip overuse issues. Mitigation strategies:

– strengthen posterior chain and hip musculature to reduce spinal loading.

– Improve thoracic mobility to reduce compensatory lumbar rotation.

– Enhance scapular stability and rotator cuff capacity.

– develop balanced eccentric and concentric capacity in the forearm and elbow musculature.

– Employ load management, progressive exposure to practice volumes, and movement retraining when technique creates adverse loading.

13. How should assessment and monitoring be integrated into practice?

Answer: Implement baseline assessments (mobility, single-leg balance, strength, power, swing kinematics) and periodic re-tests. Use daily or weekly load and wellness monitoring (RPE, pain scores, practice volume) and objective swing/club metrics when possible. Screening tools should guide individualized programming and inform return-to-play progression after injury.

14. What evidence supports the role of biomechanics in improving performance?

Answer: Biomechanics provides quantifiable metrics (e.g., kinematic sequencing, ground reaction forces, joint moments) that correlate with clubhead speed, shot dispersion, and tissue loads. Research across movement science demonstrates that analyzing and modifying mechanical variables, coupled with targeted physical training, can produce measurable improvements in movement efficiency and performance outcomes [2][3][4]. The literature on sport biomechanics more broadly supports transfer when training is specific to sport demands.

15. What are common misapplications or pitfalls when applying biomechanics to golf?

Answer: Pitfalls include:

– Overreliance on isolated metrics without considering individual variability and context.

– Training physical qualities that do not transfer because they lack specificity (e.g., high-volume isolation that doesn’t improve rotational power).

– Ignoring interaction between technique and tissue capacity-forcing a technical change without building the requisite strength/mobility.

– Excessive measurement without actionable interpretation.

16. How can coaches and sport scientists ensure transfer from gym training to the swing?

Answer: Ensure specificity of movement patterns, velocities, and joint angles; prioritize exercises that mimic swing sequencing (multiplanar, rotational, single-leg); progress load and velocity systematically; incorporate on-course or swing-integrated drills; use augmented feedback (video, launch monitor) to connect physical changes to swing outcomes; and individualize programs based on biomechanical assessment and player goals.

17. What are limitations in current golf biomechanics research and practical implications?

answer: Limitations: many studies use small samples, elite-only cohorts, or laboratory-specific protocols that limit ecological validity. Field-based variability (fatigue, course conditions, equipment differences) complicates direct translation. Practically, this requires careful extrapolation from lab findings, individualized assessment, and iterative program design grounded in both evidence and athlete response [2][3][4].

18. What future directions should research and applied practice pursue?

Answer: Promising directions:

– Longitudinal intervention studies linking specific conditioning interventions to biomechanical change and on-course performance.

– Improved field-kind measurement (wearables + AI) that reliably captures kinematics and kinetics in play contexts.

– Individualized modeling of tissue loading and injury risk.

– Integration of motor learning principles with biomechanics-informed conditioning to optimize retention and transfer.

19. How should clinicians approach return-to-play after a golf-related injury?

Answer: Use a staged, criterion-based progression:

– phase 1: restore pain-free joint mobility and control.

– Phase 2: rebuild basic strength and movement patterns with low-load, progressively challenging tasks.

– Phase 3: reintroduce golf-specific loading, power, and sequencing drills (e.g., slow swings → partial-speed swings → full-speed swings with monitoring).

– Phase 4: staged on-course exposure and practice volume increase.Use objective criteria (strength ratios, ROM thresholds, swing metrics, pain-free function) rather than time alone.

20. What practical, evidence-informed takeaways should coaches and players adopt immediately?

Answer:

– Assess mobility, single-leg control, and rotational power early to guide individualized programs.

– Prioritize hip and posterior-chain strength plus thoracic mobility and core anti-rotation control.

– Train both strength and high-velocity power; strength creates capacity that power training converts to speed.

– Monitor load and recovery to prevent overuse injuries; progress technique changes alongside physical capacity.

– Use biomechanical measurements to set specific,measurable goals and to evaluate training transfer.

References and further context

– For foundational context on biomechanics as a field and its multidisciplinary nature, see summaries from Stanford University and MIT biomechanics programs and review literature on biomechanics’ principles and applications [2][3][4]. Broad, peer-reviewed summaries of biomechanics and its application to movement science are available in review articles and resources such as Nature’s subject pages and thorough reviews [1][4].

If you would like,I can:

– convert this Q&A into a downloadable FAQ for the article.

– Provide a sample 8-12 week conditioning block (with session templates and exercise progressions).

– Develop a brief checklist for field-based biomechanical screening tailored to different golfer levels (recreational, collegiate, elite).

the integration of biomechanical insight with targeted conditioning offers a robust framework for enhancing golf performance while mitigating injury risk. Contemporary biomechanical models illuminate the kinematic sequencing and kinetic transfer that underpin effective ball-striking-principally the coordinated generation and transfer of angular and linear momentum through the pelvis, thorax and upper extremity. Conditioning strategies that prioritize rotational power, rate of force development, segmental stability, and joint-specific mobility more closely align physiological capacity with the mechanical demands of the swing than generic fitness programmes. When aligned with principles of specificity, progressive overload, and individualization, such interventions have the greatest likelihood of producing meaningful, transferable gains on the course.

Practically,this synthesis supports an integrated assessment-to-intervention pathway: objective movement and force assessments (3‑D motion analysis,force plates,validated wearable sensors) should inform individualized training prescriptions that address identified deficits in sequencing,strength,power,or mobility. Conditioning prescriptions should balance eccentric and concentric loading, neuromuscular control, and energy-system considerations, embedded within a periodized plan that respects practice, competition schedules, and recovery. Equally critically important are pragmatic load‑management and injury‑prevention strategies-screening for asymmetries, progressive return-to-play algorithms, and targeted prehabilitation for common sites of golf-related injury.

Methodologically, clinicians and researchers should continue to prioritize ecologically valid study designs that bridge laboratory biomechanics and on-course performance. Longitudinal and intervention trials that measure both biomechanical mediators (e.g., kinematic sequencing, ground-reaction force profiles) and sport outcomes (clubhead speed, shot dispersion, tournament performance) will strengthen causal inference. Advances in portable sensor technology and machine learning offer promising avenues for scalable monitoring, but must be validated against gold-standard measurements and integrated with individualized clinical judgment.

optimizing golf performance demands multidisciplinary collaboration among biomechanists, strength and conditioning professionals, physiotherapists, coaches, and sport scientists. By translating biomechanical principles into targeted, evidence‑based conditioning strategies-and by rigorously evaluating their effects on both movement mechanics and on‑course outcomes-practitioners can maximize player performance while reducing injury burden. Continued research and clinical refinement will be essential to tailor these approaches across skill levels, ages, and the diverse anatomical profiles encountered in the golfing population.

Biomechanics and Conditioning for Golf Performance

Optimizing golf performance requires more than hours on the driving range. Combining biomechanical assessment with targeted conditioning improves movement efficiency, enhances sequencing and rotational power, reduces injury risk, and turns practice into measurable on-course gains. Below you’ll find practical, research-informed guidance on golf biomechanics, fitness priorities, assessment methods, programming and drills that transfer directly to lower scores and more consistent ball striking.

What Is biomechanics and Why It Matters for Golf

Biomechanics is the science of human movement – how muscles, bones, tendons and joints produce and control motion. In golf, biomechanics examines how the body creates clubhead speed, controls the clubface, and transmits forces thru the ground and body (the kinetic chain) to the ball. For a speedy primer, see an overview of biomechanics on Britannica or Verywell Fit.

- Key outcomes from a biomechanical approach: improved power production, better sequencing (timing), reduced compensatory patterns, and fewer injuries.

- Golf keywords to remember: clubhead speed, swing mechanics, kinetic chain, ground reaction force, rotational power, thoracic mobility.

Key Biomechanical Components of the Golf Swing

1.Ground Reaction Force and Base of Support

Efficient golfers create and redirect force through their feet into the ground (ground reaction force) to amplify clubhead speed. A stable base and effective weight transfer from trail to lead leg are essential.

2. Hip and Pelvis Rotation

Hips initiate much of the downswing rotation.Good hip mobility and strength enable a powerful, controlled transfer of energy to the torso and arms without undue stress on the lower back.

3. Thoracic Spine (T-Spine) Mobility

Rotation through the mid-back (thoracic spine) allows the shoulders to turn independently of the hips. Limited T-spine rotation forces compensations through the lumbar spine or shoulders,reducing power and increasing injury risk.

4. Sequencing and Timing (Kinematic Sequence)

The ideal kinematic sequence: pelvis → torso → lead arm → club. Proper timing ensures energy flows from the ground up to the clubhead, maximizing speed while maintaining control.

5. core Stability and Force transfer

The core stabilizes the spine while transferring rotational force. Strength without stiffness is the goal – a stable midsection that still allows rapid rotation.

Assessment: How Coaches and Players Measure Biomechanics

A systematic assessment helps identify weak links and movement compensations. Assessments range from simple field tests to advanced lab-based tools.

- Screening tests: single-leg balance, overhead squat, seated thoracic rotation, hip internal/external rotation.

- Power and speed tests: medicine ball rotational throws, countermovement jump (CMJ), clubhead speed radar.

- video analysis: 2D/3D swing capture to evaluate sequencing, swing plane, and impact positions.

- force-plate and pressure-mat analysis: measure ground reaction forces and weight shift timing for advanced assessment.

Conditioning priorities for Golfers

Conditioning should be golf-specific and match the biomechanics above. The following training priorities create the foundation for power, control and durability:

- Mobility: thoracic rotation, hip internal/external rotation, ankle dorsiflexion.

- Stability: single-leg balance, anti-rotation core strength, scapular control.

- Strength: hip hinge pattern (deadlifts/hips), glute strength, posterior chain development.

- Power: rotational medicine ball throws, resisted swings, plyometrics (short, golf-specific).

- Endurance & energy systems: low-intensity aerobic conditioning for recovery between shots, and HIIT-style work for endurance during long rounds or tournaments.

Sample Exercise Types

- Glute bridges, Romanian deadlifts – posterior chain strength

- Split-stance cable rotations – anti-rotation and sequencing

- Half-kneeling chops/lifts – hip/torso dissociation and stability

- Medicine ball rotational throws – rotational power and transfer

- Single-leg Romanian deadlifts – balance and unilateral strength

8-Week Sample Golf Conditioning Plan (Weekly Focus)

Progressive sample focusing on mobility → strength → power. Train 3× per week plus 2 on-course or range sessions focused on swing work.

| Week | Focus | Key workouts |

|---|---|---|

| 1-2 | Mobility & activation | T-spine drills, hip flexor releases, glute activation |

| 3-4 | Strength (foundation) | Deadlifts, lunges, single-leg squats, core anti-rotation |

| 5-6 | power & speed | Medicine ball throws, jump work, resisted swing speed |

| 7-8 | integration & on-course transfer | Speed rounds, tempo work, simulation drills |

Drills That Turn conditioning into Better Golf Shots

- Medicine-ball rotational toss: improves hip-to-torso transfer. Progress from standing to single-leg throws.

- Step-and-rotate drill: step toward target and rotate to train kinetic sequencing and weight shift.

- Pendulum swing with tempo board: tempo and sequencing practice to sync the body with the club.

- Half-kneeling cable chop: builds anti-rotation strength and power from the core through the shoulders.

Injury Prevention: Common Golf Injuries and How Conditioning Helps

Frequent problems include low-back pain, shoulder impingement, elbow tendinopathy (golfer’s and tennis elbow) and knee issues. A biomechanics-informed conditioning program decreases the risk by addressing the root causes:

- Fix mobility limitations (thoracic and hip) to avoid lumbar over-rotation.

- Improve hip and glute strength to reduce lumbar load during rotation.

- Balance scapular stability with thoracic mobility to prevent shoulder impingement.

- Correct single-leg weaknesses to avoid compensatory stress on the knee and back.

case Study: Translating Biomechanics & Conditioning into Lower Scores

Player: 38-year-old amateur, 18 handicap. Primary issues: inconsistent ball striking,loss of distance,lower-back tightness.

- Initial assessment: limited right hip internal rotation, restricted thoracic rotation, weak glute activation and poor single-leg stability.

- Intervention (12 weeks): targeted mobility (daily thoracic rotations & hip releases), strength phase emphasizing deadlifts and single-leg work (2×/week), power phase using medicine ball throws (1×/week), integrated on-course tempo drills.

- Outcomes: clubhead speed +6 mph, fairway hits +18%, lower-back pain resolved during play, handicap dropped to 12 in 4 months.

On-Course Transfer: How to Make Fitness Work on the Range and Green

Fitness changes need repetition under golf-like conditions to transfer to the course. Use these strategies:

- Combine strength/power sessions with swing practice the same day – use fresh speed work before the range session for speed carryover.

- Practice tempo and sequencing drills immediately after power exercises to reinforce the neuromuscular pattern.

- Use on-course simulations (pressure putting, tight lies) to adapt strength gains into real-world decisions and movement control.

Testing Progress: Metrics That Matter

Track objective and subjective markers to measure progress:

- Clubhead speed and ball speed (radar)

- Carry distance and dispersion (launch monitor)

- Medicine ball rotational power and single-leg stability scores

- Self-reported pain and perceived effort during rounds

Practical Tips for Busy Golfers

- Short sessions win: 20-30 minutes of targeted mobility and activation before the range preserves time and yields big returns.

- Prioritize sleep and nutrition for recovery – strength and power gains require rest and energy.

- work with a coach or trained golf fitness professional for individualized programming, especially if you have a history of injury.

- Use technology wisely: video for swing sequencing and a simple radar for measuring clubhead speed provide actionable feedback.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

How soon will I see distance gains?

Some players notice changes in 4-8 weeks as mobility and sequencing improve. Meaningful power and strength gains typically require 8-12+ weeks of consistent training.

Do I need a gym to improve my golf fitness?

No. Many mobility, stability and power drills can be done with bodyweight, resistance bands and a medicine ball. A gym accelerates strength progress but is not mandatory.

Can conditioning fix swing technique?

Conditioning won’t replace technique coaching but it removes physical constraints (tight hips, poor stability) that limit technique. The best results come from combined biomechanical coaching and conditioning.

Additional Resources

For more on the science of movement, consider general biomechanics overviews from trusted sources such as Britannica and practical fitness insight resources like Verywell Fit. Combine that knowledge with golf-specific coaching for the moast efficient path to lower scores.