Optimizing physical preparation for golf requires the integration of biomechanical insight, physiological conditioning, and rigorous outcome measurement. Evidence-based approaches synthesize current research from biomechanics, exercise science, and sports medicine to inform training interventions that enhance swing efficiency, increase clubhead velocity, reduce injury risk, and support competitive endurance. this article synthesizes key mechanisms linking movement quality (motor control, mobility, and sequencing) wiht physical capacities (strength, power, and aerobic/anaerobic conditioning), and outlines assessment-driven, periodized strategies that translate empirical findings into practical programming for golfers across ability levels.

Precision in both practice and language matters: the descriptor “evidence-based” signals reliance on systematically gathered data rather then anecdote or analogy, and should be used with care (such as, “as evidenced by” is idiomatically preferable to the nonstandard “as evident by”). Evidence itself is an abstract construct that encompasses multiple forms-experimental trials, cohort studies, biomechanical analyses, and validated field assessments-and each carries different inferential weight. The following sections review the current evidence base, propose assessment and training frameworks tailored to golf-specific demands, and identify gaps where further research is needed to refine performance-oriented recommendations.

Principles of Evidence Based Golf Fitness: Integrating Biomechanics, physiology, and Skill Acquisition

Contemporary conditioning for golf integrates quantitative biomechanical analysis with targeted physiological profiling to create reproducible, sport-specific interventions. By combining motion-capture and club/ball outcome data with cardiorespiratory, strength, and flexibility metrics, practitioners generate a multi-dimensional athlete profile that informs objective goal-setting. Key assessment domains commonly include:

- Kinematic sequencing – pelvis-to-shoulder rotation timing and angular velocity

- Muscle capacity – rotational power, single-leg stability, and eccentric control

- Physiological readiness – anaerobic threshold, fatigue resistance, and recovery kinetics

Translation from profile to prescription relies on principles of specificity, progressive overload, and motor-control optimization. Interventions prioritize movement quality and transferability to on-course tasks, emphasizing trunk-pelvis dissociation, hip mobility under load, and coordinated lower-limb sequencing. Effective programs are characterized by layered progressions that integrate:

- Technical fidelity – drills that replicate swing constraints

- Capacity advancement – rotational power and force-transfer conditioning

- Durability – tissue tolerance and eccentric control to mitigate injury risk

Bridging physiology and skill acquisition requires intentional practice design grounded in motor-learning theory. Manipulating practice variability, feedback frequency, and attentional focus enhances retention and transfer to competitive performance. The table below summarizes assessment-to-intervention mapping commonly used in evidence-based programs:

| Domain | Typical Measure | Intervention Target |

|---|---|---|

| Rotational Power | Medicine ball throw velocity | Explosive rotational strength |

| Stability | Single-leg balance with perturbation | Ground reaction control |

| Endurance | Intermittent shuttle or RPE trends | Sustained swing quality over 18 holes |

Ongoing monitoring and iterative refinement are essential for aligning fitness gains with technical and tactical objectives.Practitioners should implement objective performance markers and athlete-reported measures to guide periodization and in-season modulation. Typical monitoring tools include:

- Biomechanical outputs – clubhead speed, sequence metrics, and impact conditions

- Physiological indicators – heart-rate variability, session RPE, and lactate trends

- Neuromuscular status – countermovement jump or force-plate asymmetry

Comprehensive Assessment and Screening Protocols for Golf Specific Movement Patterns and Injury Risk

A multidimensional evaluation framework is essential for translating biomechanical insight into practical interventions. Assessment should combine **medical and injury history**, validated patient-reported outcome measures, objective range-of-motion and strength testing, and sport-specific movement analysis captured with video or wearable sensors. This integrated approach permits differentiation between transient performance deficits and modifiable risk factors, and supports evidence-based decisionmaking when prescribing corrective, rehabilitative, or performance-oriented programming.

Practical screening batteries emphasize reproducibility and specificity to the golf swing. Core elements include the following domains, each with targeted tests and simple pass/fail or scaled scoring to aid triage:

- Mobility & joint integrity – thoracic rotation, hip internal/external rotation, glenohumeral ROM.

- Dynamic stability & motor control – single-leg squat,plank variants,Y-balance adaptations.

- Power & force transfer - medicine-ball rotational throws, single-leg hop for distance (symmetry measured).

- Movement quality - slow-motion swing capture (pelvic-thoracic dissociation, sequencing, and deceleration mechanics).

Standardizing instructions and measurement tools (goniometer, inclinometer, or inertial sensors) reduces tester error and improves longitudinal tracking.

Risk stratification should integrate test results with training load and asymmetry indices to prioritize interventions. The following concise table exemplifies actionable cut-points used in practice-based research to trigger follow-up or modification of play/training exposure.Use these thresholds as starting points for individualization rather than absolute rules; clinical context and athlete history must guide interpretation.

| Measure | At-risk threshold | Recommended action |

|---|---|---|

| hip rotation asymmetry | >15° difference | Targeted mobility & load reduction |

| Single-leg squat score | Score ≤ 3/5 | Neuromuscular control program |

| Trunk rotation power | >20% interlimb deficit | Progressive resisted rotational training |

Operationalizing assessment requires a reproducible workflow and multidisciplinary dialog. Best practice involves a **baseline battery pre-season**, prioritized red-flag screening at return-to-play, and scheduled re-assessments tied to key training phases (post-loading, mid-season, post-injury). Coaches, physiotherapists, and strength practitioners should share summarized findings and a short, prioritized action list that includes:

- Immediate – load modification and symptomatic management;

- Short-term – targeted mobility/control interventions (4-8 weeks);

- Long-term - progressive capacity and swing-integration training with objective re-testing every 8-12 weeks.

This structured, evidence-informed pathway enhances early detection of maladaptive patterns, reduces preventable injury risk, and facilitates measurable performance gains while maintaining athlete-centered care.

Strength and Power Development for the Golf Swing: exercise Selection, Load Progression, and Transfer to Performance

Contemporary evidence indicates that improvements in clubhead speed and consistency are driven by a coordinated increase in both maximal strength and the rate of force development rather than isolated hypertrophy. Emphasize the integration of neural adaptation (improved motor unit recruitment and firing frequency) with structural capacity (tendon stiffness, muscle cross‑sectional area) to create a resilient, high‑velocity delivery system. Prioritize multi‑planar, force‑transfer movement qualities that mirror the kinematic sequence of the swing: proximal-to-distal sequencing, elastic energy transfer through the core and thoracic spine, and controlled deceleration through the lead arm. strength and power work must thus be judged by transfer metrics (swing speed,ball speed,rotational RFD) rather than absolute load alone; transfer is the primary criterion for exercise inclusion.

Exercise selection should priviledge movement specificity, progressive overload, and safety. Recommended modalities include unilateral hip hinge variations (e.g., single‑leg Romanian deadlift), rotational medicine‑ball throws and chops, nordic and glute‑dominant posterior chain exercises, and high‑velocity loaded carries and sled pushes for horizontal force development. Core training should emphasize anti‑rotation and controlled rotary power rather than isolated abdominal flexion. Typical selections for a weekly plan might appear as an ordered priority: posterior chain → single‑leg stability → rotational power → deceleration/braking capacity.

- posterior chain: SLDL, hip thrusts – build torque and spinal stability.

- Rotational power: Rotational throws, cable chops – develop RFD in rotational plane.

- Single‑leg: Bulgarian split squat, single‑leg RDL – ensure force transfer through stance leg.

Below is a concise practical reference table for exercise emphasis and loading guidelines (example):

| Exercise | Primary Quality | Load guideline |

|---|---|---|

| Single‑leg RDL | Strength/Stability | 6-8 reps, 70-85% effort |

| Med‑ball rotational throw | Power (RFD) | 3-6 reps, maximal velocity |

| Trap bar deadlift | Max strength | 3-5 reps, 85-95% 1RM |

Progression must be periodized and criterion‑based: begin with a foundation phase that builds movement quality and work capacity (higher volume, moderate loads), progress to a maximal strength phase (lower reps, higher loads, 80-95% 1RM), then transition to a power/velocity phase where load is reduced and intent/velocity is maximized to convert strength into usable swing speed. Use velocity or RPE metrics to individualize progression (e.g., target mean concentric velocities for power sets, or maintain RPE 7-9 for heavy strength sets).Integrate intermeshed microcycles (e.g., concurrent strength and power within a week) for golfers with limited time, but protect quality by sequencing high‑velocity work on separate days or before fatiguing strength work. Recovery and auto‑regulation (sleep, soreness, readiness scores) should guide weekly load adjustments to avoid interference effects and preserve swing practice quality.

To maximize transfer to on‑course performance, couple gym interventions with measurable skill outcomes and structured practice. Monitor objective metrics such as 3D swing speed, ball speed, smash factor, and on‑course driving distance alongside gym markers (1RM, peak power, RFD). Use short, sport‑specific tests (e.g., med‑ball throw distance, standing rotational power) as proximal indicators of transfer. Best practice includes warm‑up potentiation routines that use light ballistic throws or short sprints to express power instantly prior to the range, and integration of fatigue‑resistant deceleration training to reduce injury risk during repetitive practice. Practical monitoring checklist:

- Gym: peak power, %1RM, velocity profiles

- On‑course/range: clubhead speed, ball speed, dispersion

- Wellness: readiness, sleep, soreness

Aligning these measures enables an evidence‑based progression that prioritizes meaningful improvements in golf performance.

Mobility, Flexibility, and Joint Stability Strategies to Optimize Swing Mechanics and Reduce Compensatory Patterns

Optimal swing mechanics emerge from a coordinated balance of joint mobility, soft-tissue flexibility, and multi-planar stability.From an academic biomechanics perspective, the golf swing is a high‑velocity, rotational task that places divergent demands on the thoracic spine, hips, shoulders, and ankles; deficits in one region often produce compensatory kinematic patterns elsewhere (e.g., excessive lumbar rotation to substitute for thoracic hypomobility). Therefore,interventions must discriminate between passive flexibility (tissue length),active mobility (usable range under neural control),and joint stability (the capacity to control motion under load). Targeted training that restores usable range while concurrently enhancing dynamic control reduces energy leakage and the propensity for maladaptive strategies such as early extension, lateral slide, or casting of the arms during the downswing.

Assessment-driven priorities should guide corrective strategies. Clinical and on‑course screens can be distilled into actionable targets:

- Thoracic rotation: seated rotation and quadruped windmill tests;

- Hip internal/external rotation: prone or supine hip ROM with femoral rotation cues;

- Glenohumeral ER/IR: sleeper and passive ER tests to distinguish capsular restrictions from scapular dyskinesis;

- Ankle dorsiflexion: weight‑bearing lunge test to assess lower‑limb chain contributions.

Interventions should prioritize the most limiting link(s) in the kinematic chain, with emphasis on restoring active, load‑bearing ranges that replicate swing positions rather than isolated static stretching alone.

Progression models must integrate neuromuscular control, load exposure, and task specificity.begin with isolated mobility and motor control drills (e.g., thoracic rotation with breath and ribcage dissociation), advance to anti‑rotation and anti‑flexion stability under incremental load (e.g., Pallof progressions, single‑leg balance with perturbations), and finally embed mobility into swing‑specific patterns (e.g., mediate hip turn into half‑swings). The following concise reference table provides representative drills, primary targets, and simple dosing to illustrate a pragmatic progression:

| Drill | Primary Target | Typical Dosage |

|---|---|---|

| Thoracic Windmill | Thoracic rotation (active) | 3×8 each side |

| 90/90 Hip CARs | Hip IR/ER control | 2-3×6 slow controlled |

| Pallof Press (band) | Trunk anti‑rotation stability | 3×10-15 sec holds |

| Single‑leg RDL | Hip stability & eccentric control | 3×6-8 each leg |

For injury prevention and long‑term performance, embed mobility/stability work within the periodized weekly plan rather than as ad hoc remedial sessions; short, high‑quality exposures (10-20 minutes) before practice and 2-3 dedicated sessions per week yield durable adaptations. Use objective monitoring (ROM re‑tests, movement quality video, wearable kinematic feedback) to detect persistent compensations and guide dose adjustments. cueing should be constraint‑based and externally focused (e.g., ”rotate chest toward target” or ”resist torso collapse”) to promote automaticity and minimize conscious overcorrections that can reintroduce compensatory patterns during high‑tempo swings.

Energy System Conditioning and Fatigue management for On Course Endurance and Decision Making

Contemporary physiological models of the sport characterize golf as an intermittent task with repeated short-duration, high-power outputs (the swing, short bursts of walking or sprinting between obstacles) superimposed on prolonged low-intensity activity (walking the course, standing, and cognitive vigilance). Effective conditioning therefore targets three complementary objectives: enhancing anaerobic power for explosive swings, improving aerobic capacity to accelerate recovery between efforts, and optimizing metabolic recovery processes (phosphocreatine repletion and lactate clearance) to preserve technical execution late in play. Practical markers for these adaptations include increased repeated-sprint ability, reduced time-to-baseline heart rate after high-intensity efforts, and maintained neuromuscular output across a simulated 18-hole test.

Training modalities should mirror on-course demands and thus combine high-intensity interval training (HIIT), tempo-specific intervals, and prolonged low-intensity endurance with load carriage to simulate bag weight. Below is an exemplar weekly microcycle that balances specificity and recovery; practitioners should individualize volumes based on player age, competitive schedule, and injury history.

| Day | primary Focus | Duration/Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Mon | HIIT + Power | 20-30 min; 6-8 x 20s all-out + 2-3 min recovery |

| Wed | Tempo / Carry Walk | 30-45 min at moderate pace with 6-8 kg bag |

| Fri | Aerobic base + Mobility | 45-60 min low-intensity walk + mobility circuit |

Fatigue monitoring and recovery interventions are critical to preserve shot execution and decision-making under cumulative load. Employ a multimodal monitoring strategy that combines objective and subjective measures:

- Physiological: resting heart rate, HRV trends, and post-effort HR recovery;

- Performance: short sprint or medicine-ball throw outputs as neuromuscular markers;

- Subjective: session-RPE, sleep quality, and perceived cognitive readiness.

Recovery prescriptions should be prioritized and periodized around competition: targeted carbohydrate timing to sustain CNS function, progressive rehydration strategies, sleep hygiene, and localized soft-tissue interventions when indicated. Evidence supports brief, strategic use of caffeine and carbohydrate during competition to mitigate transient cognitive and motor decrements associated with fatigue.

The translational objective is maintaining high-quality decision making across a round: physiological fatigue degrades working memory, visuomotor coordination, and risk assessment-all critical for club selection and shot strategy. Coaches and sport scientists should integrate conditioning outputs and monitoring data into on-course plans (e.g., pacing strategies, simplified decision rules under fatigue, altered warm-up intensity to preserve energy stores). Emphasize individualized periodization that aligns high-load conditioning blocks with recovery windows and competitive calendars, and implement simple in-play coping tactics-short pre-shot routines, scheduled micro-breaks, and predefined carbohydrate/caffeine strategies-to preserve both physical and cognitive performance late in competition.

Periodization and Individualized Program Design: Practical Templates for Offseason, Preseason, and In Season Training

Contemporary periodization for golf blends classical macrocycle segmentation with flexible, athlete-centered adjustments: a preparatory (offseason) block emphasizing capacity (hypertrophy, aerobic base, mobility), a conversion (preseason) block prioritizing power, rate-of-force development and movement specificity, and a competitive (in-season) block focused on maintenance, recovery and performance readiness. Key determinants for individualization include baseline physiological profiling (strength,power,ROM),injury history,competitive calendar,and objective load-response metrics.

- Primary objectives: capacity → conversion → maintenance

- individual modulators: age,training history,competition density

- Decision rules: performance tests and wellness + GPS/HR-derived load

For the offseason,adopt a mesocycle architecture that increases training volume and technical variance while reducing competitive stressors. Emphasize multi-planar strength, thoracic mobility, and metabolic conditioning with 3-5 strength sessions per week and 1-3 supplemental conditioning sessions. The following concise template illustrates a pragmatic 12-week block:

| Weeks | Focus | Session Density |

|---|---|---|

| 1-4 | Hypertrophy, mobility | 4 strength / 2 cardio |

| 5-8 | Max strength, eccentric control | 3-4 strength / 2 conditioning |

| 9-12 | Strength-to-power transition | 3 strength (power emphasis) / 2 sport prep |

The preseason should convert accrued capacity into golf-specific power and motor coordination by integrating on-course tempo work, rotational medicine-ball progressions, and ballistic strength training. Microcycle examples use undulating intensities (e.g., heavy strength day, power day, mobility/active recovery day) and deliberate skill integration sessions. Monitoring is essential: include weekly force-velocity or vertical jump tests, subjective readiness scales, and stroke-specific performance markers to guide progression or regression of loads.

- Emphasize velocity-specific training 2-3 weeks pre-competition

- Prioritize technical drills under fatigue to build robustness

In-season programming must preserve neuromuscular qualities while minimizing residual fatigue and injury risk; this typically means lower volume, higher specificity, and increased recovery modalities. Implement a mobility- and activation-focused warm-up protocol,two maintenance-strength sessions per week (emphasizing power preservation with low volume),and adaptable conditioning aligned with travel/congestion of events.Practical operational rules: reduce total volume by 30-50% during congested competition stretches, use objective thresholds (e.g., >15% drop in jump height) to trigger deloads, and schedule pre-competition tapering of 3-7 days based on individual response.

- Travel strategy: prioritize sleep and light activation

- Recovery toolbox: manual therapy, nutrition, sleep hygiene, compression

Monitoring, Injury Prevention, and Return to Play Protocols Using Objective Metrics and Thresholds

Contemporary practice favors routine, objective surveillance to link training exposure with musculoskeletal status and performance outcomes. Core variables that should be quantified include: swing load (session swing count × intensity), clubhead angular velocity, bilateral strength and power (isometric mid-thigh pull or handheld dynamometry), spine and hip rotational range-of-motion, trunk endurance, and validated patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) for the shoulder, hip and low back. Wearable inertial measurement units (IMUs), force plates, handheld dynamometers, and standardized clinical tests (e.g., Y-Balance, single-leg hop) provide complementary objective data streams. Routine collection enables detection of subclinical change, trend analysis, and data-driven modification of training or rehabilitation plans.

To translate monitoring into preventive action, pre-defined thresholds and decision rules are required. Adopt conservative, evidence-aligned cutoffs such as: inter-limb asymmetry >10-15% for strength/power tests, Y-Balance composite score <94% (or side-to-side reach difference >4 cm) suggestive of elevated lower-extremity risk, single-leg hop asymmetry >15%, rotational ROM deficit >10° relative to the contralateral side, and session-to-session or week-to-week swing-load spikes >20% or an acute:chronic workload ratio exceeding ~1.3-1.5. Importantly, these thresholds should be contextualized by age, playing level, prior injury history, and symptom reporting; they function as triggers for further assessment rather than absolute exclusionary rules.

Operationalizing prevention and return-to-play pathways requires an explicit protocol with monitoring cadence, escalation criteria, and multidisciplinary input. recommended workflow elements include:

- Baseline screening: comprehensive neuromuscular and ROM assessment pre-season or at initial evaluation;

- Daily/weekly monitoring: symptom checklists, session-RPE, swing counts, and selective objective tests post-high-load sessions;

- Trigger-based assessment: when thresholds are exceeded, perform focused clinical examination and movement analysis;

- Intervention ladder: modify load, institute targeted corrective exercise (rotational mobility, gluteal activation, scapular control), and re-assess at predefined intervals.

This staged, metric-driven approach reduces subjectivity and supports timely rehabilitation or load adjustments.

Clear, progressive return-to-play criteria should combine pain-free function, objective symmetry, and sport-specific capacity. A pragmatic three-stage framework is shown below (examples of numeric criteria are illustrative and should be individualized):

| Phase | Objectives | Representative criteria |

|---|---|---|

| Load Reintroduction | Restore pain-free strength and ROM | ≥90% strength symmetry; rotational ROM deficit <10° |

| Swing Integration | Rebuild swing-specific tolerance and mechanics | gradual swing-load increments ≤20% weekly; no symptom increase |

| Full Competition | Demonstrate sustained performance under match demands | ACWR within target range (~0.8-1.3); sport-specific endurance tests passed |

Decisions are most defensible when objective metrics, patient-reported symptoms, and clinical judgment converge; document each step, re-measure after interventions, and prioritize conservative progression when risk is uncertain.

Q&A

Q: What does ”evidence-based” mean in the context of golf-specific fitness?

A: In an academic context, “evidence-based” denotes practices informed by systematically gathered and critically appraised data rather than anecdote or intuition. Scientists “weigh the evidence” for and against an intervention before recommending it; this is distinct from the colloquial notion of “proof,” which implies absolute certainty (see discussion of evidence versus proof). Evidence in this usage is typically treated as a non-count concept (we talk about more evidence or further evidence rather than “an evidence”). Applying evidence-based practice to golf fitness therefore requires (1) identifying relevant empirical studies and biomechanical analyses, (2) appraising their methodological quality and applicability, and (3) translating convergent findings into individualized training and monitoring plans.

Q: What types of evidence inform golf-specific fitness protocols?

A: Evidence comes from multiple complimentary sources: randomized controlled trials and intervention studies (when available), cohort and cross-sectional studies that identify performance correlates (e.g., strength, rotational power), biomechanical studies that describe swing kinematics and joint loading, case series and clinical outcome studies for injury prevention/rehabilitation, and mechanistic laboratory research (force plates, motion capture, EMG). Meta-analyses and systematic reviews synthesize this literature and provide higher-level guidance when sufficient data exist.

Q: which physiological and performance markers are most strongly associated with golf performance?

A: Key markers supported by the literature include:

– Rotational power and rate of force development (RFD) of the torso and hips (correlates with clubhead speed).

- Lower-body strength and single-leg force production (crucial for stability and force transfer).

– Trunk stability and control through end-range rotation (sequence and timing of segmental velocities).

– Hip and thoracic spine mobility (allow efficient swing mechanics and reduce compensatory lumbar motion).

– aerobic capacity is less directly related to shot-making but contributes to fatigue resistance over a round; recovery metrics (e.g., HRV) relate to training load management.

Note: magnitudes of association vary across studies and are moderated by skill level (elite vs. amateur).

Q: What biomechanical adaptations should golf-specific training aim to produce?

A: Training should aim to enhance:

– Kinetic sequencing: improved proximal-to-distal sequencing and timely peak angular velocities.

– Increased capacity for eccentric control, especially during deceleration phases (reduces injury risk).- Greater hip and thoracic rotational ROM and usable rotational power.

– Higher peak and sustained force production through the lower limbs (improved stability and drive).

Biomechanical changes should be measured by pre/post testing using kinematic (3D motion analysis or validated wearable sensors) and kinetic (force plate) methods when possible.

Q: Which training modalities have evidence for improving golf performance?

A: A multidimensional program has the best support:

– Strength training (progressive overload targeting lower body and posterior chain) to increase maximal force.

– Power training (plyometrics, Olympic-derived movements, medicine-ball rotational throws) to improve RFD and transfer to clubhead speed.- Mobility and motor-control drills for thoracic spine, hips, and scapular-thoracic rhythm.

– Core stability with emphasis on rotational strength and anti-rotation control (integrated, sport-specific tasks).

– conditioning for work-capacity when needed (to manage fatigue over a full round or tournament).

Clinical trials are limited in number and heterogeneity, so programs should integrate principles from related fields (e.g., rotational sports) and be individualized.

Q: How should programs be periodized for golf athletes?

A: Periodization should reflect the athlete’s competitive calendar and training age:

– General preparation: build foundational strength, correct deficits, improve general mobility.

– Specific preparation: introduce power and rotationally specific drills (high-velocity medicine-ball work,ballistic lifts),increase golf-specific conditioning and swing integration.

– Pre-competition/competition: taper volume, maintain intensity, emphasize skill transfer and recovery.

– Off-season: address weaknesses, higher-volume hypertrophy or strength phases.Progression must emphasize technical transfer: strength and power gains should be regularly integrated into swing practice and measured transfer (clubhead speed, ball speed, dispersion).

Q: What assessment tools are recommended to evaluate progress and risk?

A: Recommended assessments include:

– Performance: clubhead speed, ball speed, smash factor, and dispersion metrics using launch monitors.- Physical: 1-3RM strength tests or reliable submaximal estimates; countermovement jump and single-leg hop tests; medicine-ball rotational throw distance/power; isometric mid-thigh pull or RFD when available.

– Movement quality: thoracic spine rotation ROM, hip internal/external rotation measures, trunk endurance tests, and validated screening tools (used with awareness of their limitations).

– Biomechanical analysis: 2D/3D swing kinematics or validated wearables for sequencing and tempo assessment.

– Recovery/load: subjective wellness scores, training load (session RPE), HRV for autonomic recovery trends.

Use repeated measures and reliable protocols to detect meaningful change.

Q: Which injury patterns are most common in golfers, and how can fitness training mitigate them?

A: common injuries: low back pain, shoulder (rotator cuff and labrum), elbow (medial/lateral epicondylalgia), and hip/groin issues. Fitness strategies to mitigate injury:

– enhance thoracic mobility to reduce compensatory lumbar rotation.

– Strengthen posterior chain (gluteal and hamstring complex) and improve hip control to decrease lumbar shear and excessive torsion.- Address scapular control and rotator cuff endurance for shoulder resilience.

- Include eccentric hamstring and multi-planar loading to prepare tissues for golf-specific demands.

- Implement graded return-to-play protocols and movement retraining following pain episodes.

Q: What are common misconceptions about golf fitness?

A: Common misconceptions include:

- “More flexibility is always better.” Excessive laxity without control can increase injury risk; usable mobility in combination with control is the goal.

– “Golf fitness is only about the swing.” General strength, power, and systemic conditioning influence performance and fatigue resistance.

– “Technique alone will solve physical limitations.” Technical fixes can be constrained by inadequate strength, mobility, or power; concurrently addressing physical deficits tends to be more effective.

– “Short-term gains always translate to on-course improvements.” Transfer needs to be demonstrated-improvements in lab measures must be integrated into practice to affect shot outcomes.

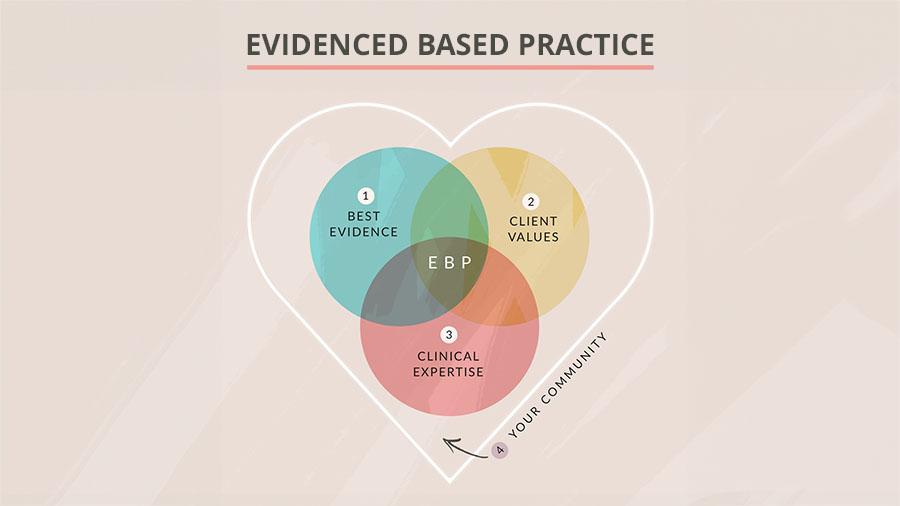

Q: How should practitioners balance scientific evidence with individualization and coach/athlete preferences?

A: Use a structured decision-making process:

1. appraise available evidence for efficacy and safety.

2. Screen the athlete for deficits and priorities (performance goals, injury history).

3. co-design a plan that integrates best evidence and the athlete’s context (time, resources, preferences).4. Monitor outcomes and adapt using objective (performance/physiological) and subjective (athlete feedback) data.

Evidence is a guide, not a prescriptive algorithm; clinical reasoning and iterative testing are essential.

Q: What metrics should researchers prioritize in future studies to strengthen the evidence base?

A: Future research should prioritize:

– Randomized controlled trials comparing multimodal, periodized interventions with active controls.

– Longitudinal studies linking training-induced changes in physical markers (RFD,rotational power) to on-course performance (shot dispersion,strokes gained).

- Standardized outcome measures (consistent launch monitor metrics, validated clinical tests).

– Mechanistic studies employing force plates and 3D kinematics to define transfer pathways.

– Larger samples across skill levels and clear reporting of training dose-response and adherence.

Q: Are there validated screening tools specific to golf fitness that practitioners should use?

A: No single screening tool has universal validation specifically for golf. Practitioners should use a combination of:

– Movement screens adapted to golf demands (thoracic rotation, single-leg stability).

– Strength and power tests with established reliability (CMJ, single-leg hop).

– Swing-specific measures (launch monitor metrics, kinematic sequencing via validated wearables or motion capture).

Use these in concert to form a profile rather than relying on a single screening instrument.

Q: What practical, evidence-aligned recommendations can coaches apply immediately?

A: Practical actions:

- Conduct a brief baseline screening: clubhead speed, unilateral lower-limb power, thoracic rotation ROM, and a movement-control test.

– Prioritize posterior chain strength (hip hinge variations), unilateral stability, and rotational power (medicine-ball throws).

– Integrate power work early in sessions (after warm-up) and promote high-quality, high-velocity movement with appropriate recovery.

– Emphasize thoracic mobility and coached segmental sequencing alongside strength work.

– Monitor training load and wellbeing (session RPE,sleep,pain) to prevent overuse.

– Progressively test transfer to swing metrics (clubhead and ball speed, dispersion) rather than assuming physiologic gains automatically improve scoring.

Q: How should practitioners interpret null or conflicting findings in the literature?

A: Interpret with caution. Conflicting findings may reflect heterogeneous samples (skill levels, ages), small sample sizes, methodological differences (outcome measures, intervention dose), or limited transfer assessment.Weigh study quality, consistency across studies, and biological plausibility. When evidence is equivocal, prefer low-risk, high-benefit approaches and prioritize individual monitoring and adaptation.

Q: Summary: What are the central academic takeaways about evidence-based golf-specific fitness?

A: Central points:

- Multidimensional, periodized programs that combine strength, power, mobility, and sport-specific integration show the greatest promise.

– Rotational power, lower-limb force production, and trunk control are consistent correlates of performance.

– Quality of evidence varies; more randomized and longitudinal work that measures on-course outcomes is needed.

– Practitioners should apply rigorous screening, individualized programming, and objective monitoring to translate physical gains into performance gains.

– Use evidence judiciously, recognizing the distinction between “evidence” (weight of data) and “proof” (absolute certainty), and apply iterative evaluation to optimize training for individual golfers.

If useful, I can convert these Q&As into a formatted FAQ for publication, provide suggested assessment protocols with sample tests, or draft a short annotated bibliography of high-quality studies relevant to specific Qs.

this review has synthesized contemporary biomechanical, physiological, and training-literature to articulate a coherent, evidence-based framework for golf-specific fitness. Core principles include individualized assessment,targeted development of rotational power and sequencing,strength and rate-of-force development,mobility and motor control,and planned periodization with sport-specific transfer.When integrated within a multidisciplinary approach-combining coaching, physiotherapy, and strength and conditioning-these elements collectively support both performance enhancement and injury reduction, as evidenced by interventional and observational studies across skill levels.

Practical implementation should begin with validated screening and monitoring (e.g., movement screens, force-velocity profiling, and workload tracking), progress through progressive overload and specificity-oriented programming, and incorporate objective performance and injury metrics to guide adaptation. Clinicians and practitioners are advised to tailor interventions to individual constraints (age, injury history, competitive demands) and to prioritize interventions with demonstrated transfer to on-course outcomes.

Limitations of the current evidence base include a relative paucity of long-term randomized trials, heterogeneity in outcome measures, and underrepresentation of certain populations (e.g., female and older golfers). Future research priorities include longitudinal, mechanism-focused interventions that quantify on-course performance transfer, standardized outcome reporting, and exploration of technology-assisted monitoring to refine dose-response relationships.

Ultimately, a disciplined, evidence-informed approach-grounded in biomechanical rationale, physiological principles, and rigorous evaluation-offers the best prospect for optimizing golf-specific fitness and safeguarding athlete health. Continued collaboration between researchers and practitioners will be essential to translate emerging evidence into effective, individualized practice.

Evidence-Based Approaches to Golf-Specific Fitness

Evidence-based principles that drive golf performance

When we talk about golf-specific fitness, we’re aiming to improve the physical attributes that directly influence swing mechanics, clubhead speed, consistency and injury resilience. The best programs combine biomechanics,sport science,and progressive training principles to produce measurable changes in performance.

Core evidence-based principles

- Specificity: Train movement patterns and energy systems that transfer to the golf swing (rotational power, anti-rotation, single-leg stability).

- Progressive overload: Gradually increase load, speed or complexity so tissue and nervous system adaptations occur.

- Individualization: Base programs on an assessment of mobility, strength, movement quality and injury history.

- Periodization: Structure training phases (accumulation, intensification, peaking/maintenance) tied to the competitive calendar.

- Measurement & feedback: Use objective metrics – clubhead speed, ball speed, swing tempo, force output - to guide progress.

Assessments and screening for golfers

Before programming, a concise assessment identifies limiting factors and injury risks. Common evidence-based screens include:

- Functional movement screen for basic movement patterns (squat, lunge, rotation)

- Thoracic spine rotation and hip internal/external rotation checks

- Single-leg balance and control (e.g., single-leg squat or Y-balance)

- Core strength and anti-rotation capacity (e.g., Pallof press, plank variations)

- Rotational power testing where available (medicine ball throw, Smash Factor testing with launch monitor)

Key physical qualities for golf (and how to train them)

Below are the primary physical attributes that evidence links to improved golf performance and practical ways to develop each.

1. Mobility & flexibility

Good mobility – especially thoracic spine and hip mobility – allows a wider shoulder turn and greater separation (X-factor) without compensatory movement that causes loss of power or injury.

- Drills: thoracic rotations on foam roller, world’s greatest stretch, hip CARs (controlled articular rotations)

- Frequency: daily dynamic mobility warm-ups + 2-3 focused mobility sessions per week

2.Stability & balance

Single-leg stability helps maintain balance through the swing and transfer force efficiently to the ball.

- Drills: single-leg Romanian deadlifts, single-leg balance with perturbations, step-ups

- Progression: add load, reduce base of support, or add trunk rotation resistance

3.Strength (general and golf-specific)

Strength underpins power production and helps sustain posture across 18 holes. Focus on hip, glute, posterior chain, and scapular/rotator cuff strength.

- Drills: deadlifts/hip hinges, squats or split squats, rows, horizontal and vertical presses

- Programming: 2-3 strength sessions per week for most golfers, 6-12 reps for hypertrophy & strength balance

4. Rotational power

Rotational power – the ability to accelerate the trunk and transfer that energy to the club – is strongly correlated with clubhead speed and distance.

- Drills: med-ball rotational throws, standing and kneeling chops/lifts, cable woodchoppers

- Progression: increase velocity, then add resisted rotational overload (band or cable), then translate to unloaded high-speed swings

5. Endurance & conditioning

Golf demands sustained muscular and postural endurance, especially on walking rounds. Conditioning helps maintain swing mechanics late in a round.

- Approach: low-moderate intensity continuous conditioning (brisk walking, cycling) + fortnightly higher intensity intervals if time permits

Sample evidence-backed exercises and progressions

| Goal | Exercise | Progression |

|---|---|---|

| Thoracic mobility | Foam roller T-spine rotation | Add band distraction or 90/90 reach |

| Single-leg stability | Split squat | Single-leg RDL with weight |

| Rotational power | Med-ball rotational throw | Heavy med-ball or standing rotational slam |

| Strength | Deadlift or kettlebell swing | Increased load or tempo variations |

Designing a golf-specific program (periodization)

A practical periodized approach yields the best long-term gains:

Microcycle (weekly example)

| Day | focus | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Mon | Strength (lower bias) | Squats, deadlift variations, single-leg work |

| Tue | Mobility + short game practice | Thoracic work, hip mobility, putting/short chip session |

| Wed | power | Med-ball throws, jump work, speed-focused swing practice |

| Thu | Active recovery | Light walk, mobility, soft tissue |

| Fri | Strength (upper bias) | Rows, presses, anti-rotation core |

| Sat | On-course play or long practice | 18 holes or long-range driver practice |

| Sun | Rest or mobility | Stretching, foam rolling |

Macrocycle guidance

- Off-season (8-16 weeks): build strength, correct deficits, increase work capacity.

- Pre-season (6-8 weeks): shift toward power growth and golf-specific speed.

- In-season (tournament or peak weeks): reduce volume, maintain strength/power, prioritize recovery and skill work.

Warm-up and pre-round routine (evidence-based & practical)

A pre-round warm-up should include dynamic mobility, activation drills and ramping speed practice swings. A simple routine:

- 5 minutes light aerobic (brisk walk) to increase circulation

- Dynamic mobility (hip swings, T-spine rotations, walking lunges) – 5-7 minutes

- Activation: glute bridges, band pull-aparts, dead-bug or pallof press – 4-6 reps each

- Speed ramp-up: 6-12 half-swings to full swings, gradually increasing intensity

injury prevention & common golf injuries

Common golf injuries include low back pain, rotator cuff issues and elbow tendinopathy.Evidence-based prevention focuses on:

- Addressing mobility restrictions (thoracic and hip mobility to reduce lumbar compensation)

- Building posterior chain strength and resilience (glutes, hamstrings)

- Scapular stabilizer and rotator cuff strengthening to protect the shoulder

- Gradual return-to-play protocols after injury and load management during tournament weeks

Testing & technology to measure progress

Objective testing adds clarity to the training process. Useful measures include:

- Clubhead speed and ball speed via launch monitor (track real-world transfer to distance)

- Med-ball throw distance or peak velocity for rotational power

- Force plate or jump testing for lower limb power (where available)

- Balance tests and single-leg endurance tests for stability insights

Use these metrics at baseline, mid-point and end of a training block to track meaningful change.

Practical tips for golfers and coaches

- Prioritize consistency over novelty – small,regular improvements beat sporadic extremes.

- Train the pattern, not just the muscle - use multi-joint exercises that replicate the swing’s kinetic chain.

- Monitor fatigue – swing quality dips with fatigue, so avoid heavy training the day before vital rounds.

- Be patient with mobility gains – improved range often requires regular, progressive work over weeks to months.

- Bridge gym to course – follow strength/power sessions with speed-focused swing practice to reinforce transfer.

12-week sample plan (high-level)

This example is a general template. Individualize loads,sets and exercises after assessment.

- Weeks 1-4 (Foundation): 3x/week strength (2 lower/1 upper) + daily mobility; med-ball throws twice weekly; 2 sessions of on-course practice.

- weeks 5-8 (Power Emphasis): 2x/week strength (lower volume, higher intensity), 2x/week power sessions (med-ball, plyo), increase speed-specific swing practice.

- Weeks 9-12 (Peaking & Transfer): Lower gym volume, 1-2 short high-intensity power sessions, high-frequency skill practice, taper volume before key rounds.

Case study: translating fitness gains to the course (example)

Golfer A (age 42, mid-handicap) completed a 12-week program focused on hip strength and rotational power. Key outcomes:

- Baseline: limited thoracic rotation, weak single-leg stability, clubhead speed 92 mph

- Intervention: targeted thoracic mobility, single-leg RDL progressions, med-ball rotational throws, 2 strength sessions weekly

- After 12 weeks: improved rotation ROM, single-leg control up 30%, clubhead speed 97-99 mph, average driving distance +8-12 yards

These results highlight how correcting mobility and building power translates to increased clubhead speed and distance - a common pattern observed in evidence-informed programs.

Resources and further reading

For coaches and players who want to dive deeper, look for peer-reviewed research on golf biomechanics, sport-specific strength & conditioning literature, and position statements from organizations like ACSM and NSCA on periodization and transfer of training.

Quick reference: practical drill checklist

- Daily: 5-10 min mobility (thoracic rotations, hip swings)

- 2-3x/week: Strength session emphasizing posterior chain & single-leg work

- 2x/week: Power session (med-ball throws, jump variations)

- Daily or pre-round: Activation and speed ramp-up swings

Use objective metrics (clubhead speed, med-ball distance, single-leg balance time) to guide progression and celebrate measurable wins. Consistent, evidence-based practice beats gimmicks – build the body so the swing can express its potential.