Optimizing golf performance requires integration of complex biomechanical, physiological, and motor-learning processes within individualized training frameworks. recent advances in sports science have challenged traditional,one-size-fits-all coaching paradigms by demonstrating that improvements in driving distance,shot accuracy,and injury resilience are most reliably achieved when interventions are tailored to an athlete’s movement patterns,strength-power profile,and neuromuscular control. As competitive levels and participation diversity increase, there is a growing imperative to translate rigorous empirical findings into practical, scalable training protocols that balance performance enhancement with long-term musculoskeletal health.

Evidence-based approaches to golf training draw on convergent lines of inquiry-biomechanical analyses of the golf swing, longitudinal studies of strength and conditioning interventions, motor learning experiments examining skill acquisition and variability, and epidemiological investigations of injury risk factors.Key performance indicators such as club-head speed, ball launch characteristics, shot dispersion, and fatigue-resistant movement efficiency serve both as outcome measures and as mechanistic targets for intervention. Methodologically robust trials, objective motion-capture and wearable sensor data, and validated physical-performance batteries now permit more precise prescription and progressive overload strategies grounded in physiological and biomechanical principles.This review synthesizes contemporary scholarship to delineate best-practice training models, highlight validated assessment tools, and identify gaps where experimental evidence remains limited.Emphasis is placed on translating research into actionable programming-integrating strength and power growth, mobility and stability training, swing-specific transfer exercises, and periodization principles-while addressing injury prevention and return-to-play considerations. By framing recommendations within an evidence-hierarchy perspective and proposing directions for future research, the aim is to support coaches, clinicians, and athletes in implementing scientifically informed strategies that optimize performance outcomes and promote athlete longevity.

Comprehensive Biomechanical Assessment to Identify Swing Deficiencies and Prioritize Corrective Interventions

High-fidelity biomechanical profiling is essential to translate laboratory findings into actionable coaching and rehabilitation strategies.A comprehensive assessment integrates three-dimensional kinematics,ground reaction forces,electromyography (EMG),and club‑tracking metrics to quantify both performance determinants and compensatory patterns. Where available, comparison to sport‑specific normative databases and the athlete’s injury history refines interpretation.Note: a preliminary web search of the provided results returned predominantly non‑biomechanical (insurance) content, so clinical judgement and peer‑reviewed literature should remain the primary references when normative data are lacking.

Core components of the protocol should be standardized and repeatable; typical measures include:

- 3D motion capture – segmental angles, sequencing, and intersegmental timing ( pelvis → thorax → arms → club).

- Force platform analysis – weight transfer, lateral forces, vertical impulse, and timing of peak force.

- Surface EMG – order/timing of key musculature (gluteus medius/maximus, erector spinae, obliques, rotator cuff) and asymmetries.

- Physical screening – hip internal/external rotation, thoracic rotation, ankle dorsiflexion, and single‑leg balance metrics.

- Club/ball telemetry – clubhead speed, attack angle, launch direction, and impact face orientation.

These elements permit objective identification of deficits in sequencing, mobility, strength, and motor control that underlie performance loss or tissue overload.

Prioritization of corrective interventions should follow a data‑driven rubric that balances performance gain against injury risk and trainability. Vital criteria include: magnitude of deviation from normative or baseline values; direct mechanistic link to outcome (e.g., loss of separation → reduced clubhead speed); contribution to cumulative tissue load; and responsiveness to targeted training. A concise decision matrix is useful for communication with athletes and multidisciplinary teams:

| Criterion | Example | Typical priority |

|---|---|---|

| Performance impact | Reduced X‑factor | high |

| Injury risk | Asymmetric lateral force peak | High |

| Trainability | Poor thoracic rotation | Moderate |

| Time to change | neuromuscular timing | Low-Moderate |

this framework ensures that immediate safety and high‑leverage performance deficits are addressed first, while longer‑term motor patterns are integrated into periodized training.

Implementation requires an iterative process of targeted interventions, objective monitoring, and reassessment.Begin with short‑term corrective blocks (mobility, activation, load management) that precede technical retraining to avoid reinforcing compensations. Employ readily tracked metrics – e.g., time to peak pelvis rotation, peak ground reaction asymmetry, and clubhead speed – as progress markers, and schedule reassessments at pre‑specified milestones (4-8 weeks). Emphasize interdisciplinary communication: concise, evidence‑based reports that combine quantitative outputs with prioritized action items facilitate translation from assessment to on‑course performance gains while reducing injury risk.

applying Periodized Strength and Power Programming to Maximize Clubhead speed and shot Consistency

Structured periodization aligns neuromuscular adaptations with competitive scheduling by sequencing phases that emphasize hypertrophy, maximal strength, and then power-specific work. Empirical evidence supports a block-style model for golfers, where a 4-8 week strength accumulation phase is followed by a concentrated 3-6 week power conversion block and a short peaking/taper prior to key events. This sequential approach optimizes motor unit recruitment and intermuscular coordination while reducing training interference between high-volume strength work and high-velocity power expression.

Exercise selection and transfer prioritize multi-joint,spine-stabilizing movements and rotational power drills that mimic swing kinematics. Foundational lifts (trap bar deadlift, split squat, and horizontal press) are complemented by rotational medicine ball throws, rotational Olympic-derivative lifts, and band-resisted swing accelerations. Emphasis should be placed on rate of force development (RFD) and stretch-shortening cycle integrity; therefore, training should integrate both heavy (>85% 1RM) strength stimuli to increase maximal force and low-load ballistic efforts (<40% 1RM or bodyweight) executed at maximal intent to enhance velocity-specific adaptations.

Monitoring and progression use objective metrics to refine periodization and individualize load. Practitioners should employ a combination of velocity-based training (VBT) outputs, launch monitor clubhead speed, and force-plate-derived asymmetry/RFD measures to detect readiness and adaptation. Progression rules include systematic increments in peak concentric velocity, preserved or rising clubhead speed in the face of increased strength, and maintenance of movement quality under sport-specific loading. When markers plateau or deteriorate,prioritize technique-driven deloads or increased power density rather than indiscriminate volume escalation.

Key implementation elements can be summarized as practical checkpoints for coaches and players:

- Phase sequencing: hypertrophy → strength → power → taper

- Dual-target loading: heavy strength + ballistic velocity work

- Objective gating: VBT, launch monitor, force plate metrics

- Recovery modulation: planned deloads and pre-competition taper

| Phase | Primary Focus | Representative Intensity |

|---|---|---|

| Accumulation | Hypertrophy & work capacity | 60-75% 1RM |

| Transmutation | Max strength & control | 80-95% 1RM |

| Realization | Power & velocity transfer | Ballistic & ≤40% 1RM |

Targeted Mobility and Movement Quality Interventions to Restore Functional Range and Reduce Injury Risk

Contemporary rehabilitation and performance paradigms in golf prioritize restoration of joint-specific mobility and global movement quality to re-establish an efficient kinematic sequence and reduce cumulative load on vulnerable tissues. By targeting deficits that disrupt thoracic rotation,hip internal rotation,ankle dorsiflexion,and scapulo-thoracic mechanics,clinicians can address the biomechanical drivers of swing compensations. The approach is inherently task-specific: mobility work is selected and dosed according to swing demands and backed by objective measures rather than generic stretching prescriptions. (Note: the term “targeted” is the accepted standard spelling in current literature and usage.)

Interventions emphasize high-quality, region-specific techniques integrated with motor control training to embed new ranges into sport-specific patterns. Core components include:

- Joint-specific mobility drills (e.g., thoracic extensions over a foam roller, hip internal rotation with banded assistance) performed in a controlled, loaded context.

- Movement quality progressions that link passive range to active control (e.g., half-kneeling chop variations, resisted band rotations, single-leg balance with trunk rotation).

- Neuromuscular re-education using low-load, high-signal exercises to improve timing and sequencing within the swing kinematic chain.

Assessment-driven programming ensures interventions are evidence-aligned and measurable. Practical metrics for monitoring include passive and active range-of-motion (ROM), symmetry indices, and velocity- or power-based performance correlates. The table below summarizes concise assessment targets and their rationale for golf-specific mobility work.

| assessment | Practical Target | rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Thoracic rotation (A-ROM) | ≥45° each side | Facilitates backswing and reduces lumbar shear |

| Hip internal rotation | ≥30° | Supports pelvis sequencing and weight transfer |

| Ankle dorsiflexion | ≥10-15° | Improves squat depth and ground force application |

Translation of restored mobility into injury resilience requires systematic integration with strength and power phases and ongoing autoregulation based on athlete response. use frequent short-form reassessments (e.g., weekly ROM checks, pain scales, swing-feel reports) and objective performance markers (clubhead speed, ball-flight consistency) to progress from isolated mobility to loaded, dynamic practice. Emphasize progressive specificity: once the desired range is reproducible under control, advance to ballistic and rotational power work that replicates swing velocities. The overarching principle is simple yet pivotal-apply targeted, measurable interventions that close the gap between available range and sport-specific demands to sustainably reduce injury risk and enhance performance.

Integrating Motor Learning Principles and Variable practice to Enhance Skill Retention and on-Course Transfer

Contemporary motor learning theory provides a principled basis for structuring practice that promotes durable skill acquisition and ecological transfer to competitive settings. Empirical constructs such as schema theory, specificity of practice, and transfer-appropriate processing explain why variability during training produces more adaptable sensorimotor representations than repetitive, invariant drills. whereas performance during an isolated practice session is often optimized by low-variability, high-repetition routines, long-term retention and on-course transfer are enhanced when practice samples the statistical and perceptual-motor conditions typical of play. In short, the goal of training design should prioritize representational richness over short-term gains in performance metrics.

Practically, this translates into deliberately manipulating informational and task constraints to create functional variability. High contextual interference (e.g.,randomizing shot types) and varied environmental contexts (turf conditions,wind simulation,discrete time pressures) encourage learners to reconstruct movement solutions rather than rely on a single stored pattern. Recommended manipulations include:

- Club and lie variability: cycle through different clubs and irregular lies within the same practice block.

- Task-mix scheduling: use randomized sequences of short, mid, and long shots instead of blocked sets.

- Perceptual perturbations: vary visual cues, target sizes, and crowd/noise simulations.

- Temporal constraints: introduce variable pre-shot routines and time pressure to mirror on-course demands.

Feedback design is equally critical: augmented feedback should be reduced and structured to foster error-detection and self-regulation. Strategies supported by motor learning research include faded feedback schedules, summary feedback, and bandwidth feedback that only signals significant deviations.Combining reduced feedback frequency with opportunities for learner-controlled feedback enhances autonomy and retention. Additionally, emphasizing an external focus of attention (e.g., ball trajectory or target-oriented imagery) and using analogical instructions can accelerate implicit learning and robustness under pressure. Error-based practice-allowing controlled exploration and correction-builds resilience and transferability more effectively than perfect-execution repetition.

Translating these principles into a periodized training plan requires clear monitoring and periodic transfer assessments. Implement retention tests after delayed intervals (24-72 hours, then 1-4 weeks) and schedule on-course transfer sessions that replicate competitive constraints. The table below summarizes common practice manipulations and their expected short- and long-term impacts, useful for programming decisions in weekly microcycles and seasonal macrocycles.

| Practice Manipulation | Immediate Performance | Retention & Transfer |

|---|---|---|

| Blocked repeats (low variability) | High short-term accuracy | Poorer transfer; fragile under pressure |

| Randomized task-mix | Lower immediate scores | Improved retention and on-course adaptability |

| Faded/summary feedback | Slower short-term learning | Greater self-regulation and long-term gains |

| Perceptual/environmental variability | variable session outcomes | Enhanced decision-making and robustness |

Monitoring Training Load, Fatigue, and Recovery with Objective Metrics and Individualized Adjustments

Contemporary frameworks conceptualize monitoring as a systematic, periodic process to collect, analyze and apply data for active management of performance and risk; this aligns with definitions that emphasise continuous observation and details use to maximise positive outcomes and minimise adverse impacts. In golf, such monitoring translates into establishing individual baselines, tracking deviations in physiological and performance markers, and integrating those signals into training decisions to preserve shot quality, power, and tissue health. The emphasis is on longitudinal trend analysis rather than single-point measures: transient fluctuations should prompt contextual inquiry, whereas sustained deviations trigger planned intervention.

Objective indicators span biomechanical, autonomic, neuromuscular and behavioural domains. Commonly employed metrics include:

- Session-RPE (sRPE) – internal load estimate combining duration and perceived intensity; practical and validated for load quantification.

- Swing/shot volume and high-load swing counts – practice-specific external load relevant to cumulative tissue stress.

- HRV and resting heart rate – autonomic markers sensitive to recovery status and global physiological strain.

- Countermovement jump (CMJ) or grip strength – rapid neuromuscular fatigue screens reflecting readiness for power demands.

- Wearable IMU-derived metrics (peak clubhead acceleration, peak trunk rotation velocity) – objective proxies for mechanical load and technique drift.

- Sleep quantity/quality and subjective soreness – behavioural and perceptual inputs that modify risk and adaptation.

| Metric | Suggested Frequency | Individualised Action threshold |

|---|---|---|

| sRPE (weekly load) | Daily logging, weekly summary | Persistently >20-30% above 4‑wk mean → reduce volume/intensity |

| HRV (RMSSD) | Daily (morning) | Drop >10-15% from personal baseline for 3 consecutive days → prioritise recovery |

| CMJ peak power | 2-3×/week or pre-session | Drop >5-10% vs baseline → modify high-power loads |

translating metrics into training adjustments requires pre-defined, individualised rules and multidisciplinary oversight. Evidence-based responses include short-term volume reductions (e.g., 20-40%), substitution of high-load technical repetitions with low-load motor-patterning, scheduled deload weeks every 3-6 weeks, and targeted recovery interventions (sleep optimisation, nutrition, soft-tissue management, and light aerobic activity). Crucially, practitioners should prioritise trend-based decision-making, combine objective data with athlete-reported context, and tailor interventions to the player’s competitive calendar and injury history to balance adaptation with risk mitigation.

Nutrition, Sleep, and Regenerative Strategies to Support Adaptation and Accelerate Return to Peak Performance

Optimal adaptation to golf-specific training requires a coordinated approach that integrates nutrition, sleep, and targeted regenerative modalities. Evidence-based nutritional strategies emphasize **adequate energy availability** and macronutrient distribution to support repeated bouts of skill work and resistance training; these principles align with global dietary guidance such as the WHO healthy-diet framework and clinical nutrition counseling approaches described by the Mayo Clinic. Nutrition should be viewed as a periodized input-adjusted by session intensity, duration, and the athlete’s developmental stage-to maximize neuromuscular learning, sustain on-course concentration, and minimize injury risk.

Practical fueling and recovery prescriptions should be simple, reproducible, and sport-specific. Key tactical recommendations include:

- Pre-round: a mixed carbohydrate-protein meal 2-3 hours prior (e.g., whole-grain sandwich with lean protein) to maintain glycemia and cognitive focus.

- During play: easily digested carbohydrates (15-30 g per hour for prolonged play), regular fluid intake, and electrolyte consideration in hot/long rounds.

- Post-session: a recovery bolus containing ~20-30 g of high-quality protein plus carbohydrates to support muscle repair and glycogen restoration when multiple sessions occur in the same day.

Sleep and regenerative practices are non-negotiable modulators of adaptation. Aim for consistent nocturnal sleep duration and quality (typically ~7-9 hours for adults), prioritize sleep timing relative to training and competition, and incorporate short-term restorative strategies-controlled naps, moderate-intensity active recovery, and compression/massage for symptom relief. Use regenerative interventions judiciously: for example,**cold-water immersion** can accelerate perceived recovery and reduce soreness but may attenuate long-term hypertrophic adaptations if used instantly after resistance-based performance sessions; thus,apply modality selection according to the training goal (acute recovery vs. chronic adaptation).

Monitoring small, objective markers facilitates individualized recovery dosing and timely return to peak performance. Useful metrics include resting heart rate variability,subjective wellness scores,sleep duration/efficiency,body-mass trends,and urine color. Table 1 provides a concise monitoring checklist to translate data into action.

| Marker | Practical Threshold | Action |

|---|---|---|

| Sleep duration | <7 h/night (concern) | Prioritize earlier bedtime; limit late caffeine |

| Perceived recovery | Scale <6/10 | Reduce intensity; add active recovery |

| Body-mass change | ±2% rapid loss | Assess hydration, increase fluids/electrolytes |

- Implement progressively: introduce nutritional and recovery changes over weeks, not days, and document responses.

- Collaborate: involve coaches, sports dietitians, and medical staff when available to tailor plans for developmental athletes.

Translating assessment data into Practice through Multidisciplinary Collaboration and Periodic Performance Reassessment

Assessment outputs-ranging from high-speed motion-capture kinematics and launch-monitor metrics to physiological screening and cognitive load measures-must be converted into actionable prescriptions by a coordinated team. Drawing on the conventional definition of multidisciplinary practice as the engagement of multiple distinct fields, the rationale is pragmatic: each dataset aligns with specific expertise (e.g., biomechanics, strength & conditioning, sports psychology, physiotherapy, coaching) and requires domain-specific interpretation before being integrated into a coherent training plan. When translated this way,raw metrics become targeted interventions rather than isolated observations.

Operationalizing results requires a structured workflow that ensures reproducibility and clinical-like governance. key components include a secure shared database, standardized reporting templates, and scheduled case conferences that use evidence hierarchies to prioritize interventions. Typical outputs created through this workflow are:

- Individualized practice prescriptions (drill selection, rep ranges, session sequencing)

- Load-management protocols (progressive strength, mobility constraints, recovery windows)

- Technical interventions (swing-change targets anchored to objective kinematic thresholds)

- Mental-skills programming (attention strategies and arousal modulation tied to performance states)

| Assessment Domain | Lead Professional | Reassessment Cadence |

|---|---|---|

| kinematic & ball-flight | Biomechanist / Coach | 4-8 weeks |

| Strength & movement screening | S&C Coach / Physiotherapist | 6-12 weeks |

| Psychological readiness | Sport Psychologist | Monthly or pre-competition |

| Fatigue & recovery biomarkers | Performance Analyst / Medical | Weekly to biweekly |

Periodic reassessment is not merely a calendar task but the mechanism for iterative refinement: define key performance indicators (KPIs), set statistical thresholds for meaningful change (e.g., smallest worthwhile difference, confidence intervals), and embed decision rules that trigger modification of the plan. Recommended schedule examples (adapted to athlete level and training phase) are: weekly micro-checks for recovery and pain, monthly technical reviews, and quarterly holistic evaluations. this adaptive loop-assessment, interpretation, intervention, reassessment-creates a learning system in which multidisciplinary expertise converges to optimize transfer from practice to competition while minimizing injury risk.

Q&A

below is a scholarly Q&A intended to accompany an article entitled “Evidence‑Based Approaches to Golf Training Optimization.” The questions address conceptual foundations, assessment and monitoring, programming and periodization, transfer to on‑course performance, injury prevention, and practical implementation. Answers synthesize contemporary applied exercise‑science principles with biomechanical and performance measurement considerations. Language notes about the term “evidence” and related phrasing are provided at the end.

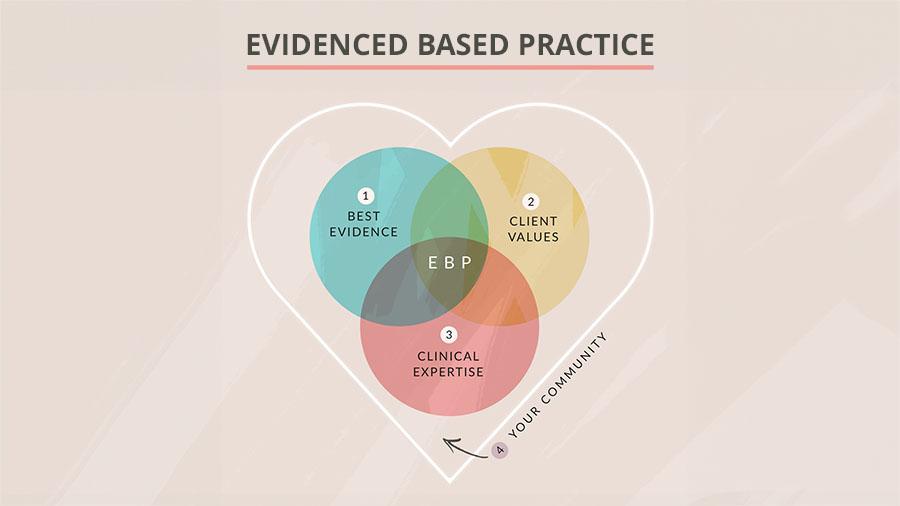

1) What do we mean by “evidence‑based” in the context of golf training optimization?

Answer: evidence‑based golf training integrates the best available scientific evidence (biomechanics, exercise physiology, motor control, injury epidemiology) with systematic measurement and practitioner expertise to design, implement, and evaluate interventions that aim to improve golf‑specific performance (e.g., clubhead speed, ball speed, shot dispersion, strokes gained). It emphasizes reproducible assessment, quantified targets, and iterative adjustments based on objective outcomes rather than purely anecdotal practice.

2) What are the primary physiological and biomechanical determinants of golf performance that training should target?

Answer: Key determinants include:

– Lower‑body and posterior chain strength and power (force production into the ground and transfer through the kinetic chain).

– Trunk rotational power and segmental sequencing (plyometric/rotational speed and eccentric control).

– Hip internal/external rotation and thoracic rotation mobility for swing range and sequencing.

– Shoulder and scapular stability for control at impact and follow‑through.

– Rate of force development (RFD) and velocity‑specific power for increasing clubhead speed.

– Aerobic and anaerobic conditioning sufficient to maintain technical execution and decision making across a round or tournament.

Training should prioritize qualities that transfer to swing mechanics and shot outcomes.3) How should an evidence‑based assessment battery for golfers be structured?

Answer: Assessments should be multidimensional, repeatable, and linked to outcomes:

– Baseline health/screening: medical history, pain, past injury, movement screens to identify red flags.

– Mobility/stability: thoracic rotation, hip internal/external rotation, ankle dorsiflexion, shoulder ROM.- Strength/power: isometric mid‑thigh pull or 1RM squat/hip hinge, countermovement jump (CMJ) metrics, single‑leg hop tests, medicine ball rotational throw.

– Velocity/power specificity: rotational power tests (seated or standing med‑ball throw), unloaded and loaded swing drills with launch monitor.

– Biomechanics (when available): 2D/3D swing kinematics, ground reaction force/time sequencing.

– on‑course/performance metrics: clubhead speed, ball speed, launch angle, spin rate, shot dispersion, strokes gained.

Reassess every 4-8 weeks to evaluate adaptation and transfer.4) What principles should guide the design of a golf‑specific training program?

Answer:

– Specificity: exercises replicate the direction, velocity, and coordination demands of the golf swing.

– Progressive overload: gradually increasing mechanical or metabolic load to drive adaptation.

– Strength → power sequencing: build maximal strength before emphasizing high‑velocity power to maximize transfer.

– Individualization: tailor to player’s deficits, injury history, and competitive schedule.

– Integration: combine S&C with technical practice and on‑course training; avoid treating them as isolated.

– Monitoring and recovery: manage training stress and include recovery modalities to reduce injury risk.

5) how should strength and power be periodized for golfers?

Answer: Use a functional periodization model aligned to the competitive calendar:

– Preparatory (off‑season): emphasis on hypertrophy and maximal strength (6-12 weeks) and correcting deficits.

– Specific preparation (pre‑season): convert strength to sport‑specific power and RFD (4-8 weeks) with ballistic and rotational exercises.

– Pre‑competition: peak power and speed maintenance; reduce volume but maintain intensity and specificity.

– Competition: prioritize recovery, technical practice, and short maintenance sessions (low volume, high quality).

– transition: active rest and rehabilitation as needed.

Microcycles typically include 2-3 strength sessions plus 1-3 speed/power or mobility sessions, adjusted by player level and schedule.6) What exercises and training modalities show the best transfer to increased clubhead speed and shot performance?

Answer: Multimodal interventions that emphasize force production, rotational power, and swing‑specific velocity tend to transfer best:

– Bilateral and unilateral posterior chain lifts (trap bar deadlift, Romanian deadlift, single‑leg RDL).

– Hip hinge and horizontal force development (hip thrusts).

– Heavy strength to build force capacity, followed by ballistic and plyometric exercises (jumping, medicine‑ball rotational throws, rotational plyos).

– Speed‑strength drills: band resisted swings, overspeed drills (cautiously), and high‑velocity cable/chop patterns.

– technical integration: repeated full‑swing practice with launch monitor feedback to ensure neuromuscular transfer.

Evidence supports sequencing heavy strength training before power work to maximize translation to high‑speed sport actions.7) How should monitoring and load‑management be implemented?

Answer: Combine internal and external load measures:

– Internal: session RPE, pain scores, wellness questionnaires, heart rate variability if used.

– External: volume/load in the weight room, jump/velocity outputs, number of swings, distance walked, on‑course shot counts.

– Performance markers: clubhead speed, ball speed, shot dispersion, launch monitor data.

Use thresholds for escalation and de‑load (e.g., sustained drop in RFD or clubhead speed, persistent high sRPE, increasing pain). Regular data review enables evidence‑based adjustments.

8) Which injury risks are most common in golfers and how can training prevent them?

Answer: Most frequent injuries: low back pain,lateral epicondylalgia (golfer’s/tennis elbow variations),shoulder impingement/rotator cuff strains,hip/groin problems. Preventive strategies:

– Address modifiable risk factors: poor thoracic mobility, restricted hip rotation, weak posterior chain, poor scapular control.

– Eccentric strengthening for decelerative muscles (rotator cuff,forearm).

– Core control with rotational stability and anti‑rotation exercises.

– Progressive swing loads following rehabilitation, and graded return‑to‑play protocols.

– Load management to avoid sudden spikes in swing volume or intensity.

9) How do you measure transfer from gym interventions to on‑course performance?

Answer: Use both proximal and distal outcome measures:

– Proximal: biomechanical improvements (e.g.,increased peak trunk rotational power,improved force‑time profiles).

– Distal: improvements in clubhead speed, ball speed, smash factor, launch characteristics, shot dispersion, strokes gained.

Statistical and practical meaning must be considered: quantify change relative to reliability (smallest detectable change) and determine whether changes affect scoring (e.g., strokes gained). Randomized controlled designs are ideal but often impractical; repeated measures and case series with objective metrics are commonly used.

10) What practical constraints limit evidence‑based practice in golf, and how can they be mitigated?

Answer: Constraints include limited high‑quality longitudinal rcts in golfers, variability between individual athletes, equipment/access limitations (force plates, 3D analysis), and organizational barriers. Mitigations:

– Use best available evidence and triangulate across study designs.

– Implement robust within‑subject monitoring and n‑of‑1 approaches.

– Prioritize affordable, validated tools (portable launch monitors, linear position transducers, CMJ with contact mats).

– Foster interdisciplinary collaboration (coach, S&C, biomechanist, physiotherapist).

11) What is an example 4‑week mesocycle for an intermediate golfer aiming to increase clubhead speed?

Answer: Example (3 strength sessions, 2 power/speed sessions, 1-2 mobility/recovery sessions per week):

– Week structure: Mon (Power/Rotational speed + mobility), Tue (Strength lower body heavy), Wed (Active recovery + technical practice), thu (Strength upper body & posterior chain), Fri (Speed/power ballistic + on‑course practice), Sat (Light maintenance strength or mobility), Sun (Rest).

– Progressive overload: Weeks 1-2 build load/intensity; Week 3 peak power sessions; Week 4 reduce volume for recovery and testing (post‑cycle assessments).

– Include med‑ball rotational throws, heavy hip hinge lifts, single‑leg stability work, and technical swings with launch monitor feedback.

12) How frequently enough should practitioners re‑test and update training prescriptions?

Answer: Retesting intervals of 4-8 weeks balance sensitivity to change with training stability. Use shorter monitoring windows (weekly sRPE, jump metrics, clubhead speed checks) to detect early trends. Update prescriptions when objective measures show plateau, regression, or when competitive scheduling requires adjustment.

13) What research directions would strengthen the evidence base for golf training optimization?

Answer: Priorities:

– Controlled longitudinal studies linking specific S&C interventions to on‑course outcomes (strokes gained, tournament performance).

– Mechanistic studies connecting changes in kinematics/kinetics to performance metrics.

– Dose‑response research to define optimal volumes and intensities for speed/strength transfer in golfers.

– Studies on individualized interventions, injury prevention efficacy, and rehabilitation protocols with robust outcome reporting.

14) How should practitioners communicate evidence to athletes and stakeholders?

Answer: Adopt obvious, pragmatic communication: present expected effect sizes, time course for improvements, measurement methods, and potential risks. Use objective data visualizations when possible, define short‑term milestones, and emphasize the integration of technical practice with physical preparation.

15) Language note – correct usage of the term “evidence” and related phrases

answer: In academic writing be precise: “evidence” is typically a non‑count noun (use “more evidence” or “piece of evidence” rather than “an evidence”) and “evidence‑based” is a correct adjectival form.Say “as evidenced by” rather than “as evident by” (the latter is nonstandard). Usage of “evidence” as a verb (e.g., “the study evidenced that…”) is absolutely possible but less common; choice verbs such as “indicated” or “demonstrated” are frequently preferred for clarity (see discussions of usage). [Note: see usage guidance from available language resources on evidence/evidenced phrasing.]

Concluding remark

Evidence‑based golf training requires the integration of valid assessment, principled program design, ongoing monitoring, and close collaboration among coaches, S&C specialists, and clinicians. It emphasizes measurable targets (both biomechanical and scoring outcomes), individualization, and iterative adjustment informed by objective data.

If you would like,I can: (a) produce a printable assessment checklist tailored to club level and elite golfers; (b) create a sample 12‑week periodized plan for a specified player profile; or (c) draft brief summaries of the strongest peer‑reviewed studies that support specific intervention types. Which would you prefer?

the corpus of contemporary research supports a multifactorial, individualized approach to golf training optimization: interventions that integrate sport-specific strength and power development, mobility and motor-control training, biomechanical refinement, and monitored load-management produce the most consistent gains in performance while reducing injury risk. Objective physiological and biomechanical markers (e.g., rate of force development, rotational power, movement-quality metrics, and validated workload indices) should be used to guide prescription, progressions, and return-to-play decisions.

For practitioners and applied researchers, the practical implications are clear. coaches,strength-and-conditioning specialists,and medical professionals should collaborate within interdisciplinary frameworks to translate evidence into scalable,context-sensitive programs; employ regular assessment and data-driven adjustments; and balance short-term performance objectives with long-term athlete health. Adoption of standardized outcome measures and transparent reporting of interventions will enhance comparability across studies and aid implementation in practice.

Future inquiry should prioritize methodologically rigorous designs (including randomized controlled trials where feasible), longer follow-up periods, and harmonized outcome reporting to strengthen causal inferences and inform best-practice guidelines. precise scholarly language matters: when discussing collective findings, use uncountable forms (such as, “further evidence” or “additional evidence” rather than “another evidence”) to maintain clarity and academic rigor. By aligning training practice with robust, continually refined evidence, the field can advance toward safer, more effective pathways for optimizing golf performance.

Evidence-Based Approaches to Golf Training Optimization

why evidence-based golf training matters

Optimizing golf performance requires more than “hit more balls.” Evidence-based golf training blends biomechanics, sport science, and data-driven coaching to improve swing efficiency, increase swing speed and driving distance, reduce injury risk, and sharpen the short game. Below you’ll find practical,research-aligned approaches-organized for coaches and serious players-that target the full golfer: mechanics,movement,strength,and recovery.

Key assessment tools for data-driven golf training

Effective optimization starts with assessment. Use objective tools to establish baselines and measure progress:

- Launch monitors (TrackMan, GCQuad, FlightScope) – ball speed, launch angle, spin, carry and dispersion for data-driven swing adjustments.

- Motion-capture & inertial sensors (K-Motion, Vicon, wearable IMUs) – 3D kinematics of pelvis, thorax, and wrist action to analyze sequencing and X-Factor.

- Force plates & pressure mats – ground reaction forces and weight transfer patterns during the swing.

- Performance tests – 1RM or velocity-based strength tests, jump tests, and rotational power assessments.

- Movement screens – functional movement screening (FMS), Y-Balance, hip internal/external rotation and thoracic mobility tests to identify limitations and injury risk.

- Physiological monitoring – heart rate variability (HRV), sleep tracking, and subjective wellness scales to manage training load.

Biomechanical analysis: improve swing efficiency

Biomechanics helps you identify what to change and what to preserve. Key targets include creating optimal sequencing, preserving width and radius, improving hip-shoulder separation (X-Factor), and delivering a square clubface at impact.

What to measure

- Pelvis and torso rotational velocities and timing

- Lead arm and wrist lag angles (shaft lean and release patterns)

- Center of pressure shifts and weight transfer timing

- clubhead speed and smash factor

Practical interventions

- Use slow-motion video and sensor data to isolate sequence faults.

- Apply drills that reinforce correct kinematic sequencing (e.g., “step” drills, pause-at-top drills, and resistance-banded rotation drills).

- Combine short technical sessions with strength and mobility work to ensure mechanical improvements are supported by the body.

Strength, power, and conditioning for golf

Golf performance depends on rotational power, single-leg stability, and the ability to generate force quickly. Evidence supports targeted strength and power training to increase swing speed, driving distance, and consistency of contact.

Training priorities

- Rotational power: medicine ball throws (rotational chops, overhead slams), cable chops, and resisted swings.

- Lower-body force production: squats, split squats, and loaded single-leg work to improve stability and ground reaction force generation.

- hip and core strength: anti-rotation presses, pallof presses, and glute-focused exercises.

- Rate of force development: Olympic movement variations, kettlebell swings, and jump training (plyometrics).

Sample set/rep guidelines

Use a mix of strength (3-6 reps, 3-5 sets), hypertrophy for resilience (6-12 reps), and power (<6 reps with explosive intent). integrate velocity-based training or RPE to manage intensity for golfers at all levels.

Mobility, movement screening, and injury prevention

Mobility and joint control are essential to produce a powerful, repeatable golf swing while minimizing injury risk-especially low back and wrist issues.

Common mobility deficits in golfers

- Restricted thoracic rotation

- Limited lead hip internal rotation

- Poor ankle dorsiflexion affecting setup and weight shift

- Shoulder capsule restrictions impacting takeaway and follow-through

Corrective strategies

- Joint-specific mobility drills (thoracic rotations, 90/90 hip switches).

- Dynamic warm-ups that mimic swing demands (banded rotations, hip CARs).

- Progressive stability work to control new ranges (single-leg balance with rotational reach).

Skill acquisition: practice structure & motor learning

Better practice design yields better carryover to the course. Use motor learning principles-deliberate practice, variability, and appropriate feedback-to accelerate skill transfer.

evidence-based practice tips

- Blocked vs. random practice: Blocked practice is useful for early technical change; random practice (mixing clubs and shot types) improves retention and on-course adaptability.

- Short, focused sessions: 20-45 minute high-quality practice beats 2-3 hours of mindless hitting.

- Use immediate and summary feedback: launch monitor numbers give objective feedback; occasional video or coach feedback supports technical learning.

- Perceptual variability: Practice in changing conditions (wind, lie, pressure scenarios) to improve decision-making and shot selection.

Putting and short game: high value, low effort

A large proportion of strokes are lost inside 100 yards. Evidence shows that short game and putting practice yield big ROI in scoring.

- focus on distance control drills and uphill/downhill reads rather than only alignment.

- Use the “gate drill” for stroke path and the “ladder drill” for distance control to build reliable feel.

- Practice pressure putting-games and bets to simulate on-course stress-improves clutch performance.

Load management,recovery,and long-term progress

Training optimization is as much about recovery as it is about work. Implement progressive overload with planned deload weeks and track fatigue to avoid burnout and injury.

Recovery tools & strategies

- Prioritize sleep and nutrition to support adaptation.

- Use HRV and subjective wellness scores to adjust training load.

- Active recovery sessions (mobility, light aerobic work) during high-volume periods.

Monitoring success: metrics that matter

Track both performance outcomes and health markers. Useful metrics include:

- Clubhead speed and ball speed improvements

- Carry distance and dispersion (left/right spread)

- Short game proximity to hole (e.g., average GIR to hole-out distance)

- Mvmt screening enhancement (thoracic rotation degrees, hip internal rotation degrees)

- Strength and power gains (e.g.,medicine ball rotational throw distance)

Sample 12-week microcycle & periodization (example)

Below is a simple weekly microcycle you can adapt. Rotate intensity across weeks and include one deload week every 4th week.

| Day | Morning | Afternoon/Evening |

|---|---|---|

| Mon | Strength: lower-body focus (3x heavy) | Short game practice (45 min) |

| Tue | Mobility + thoracic work (20 min) | On-range: technical swing work (30-45 min) |

| Wed | Power: med-ball throws & plyos (30 min) | Putting session (30 min) |

| Thu | Active recovery (bike/walk, 20-30 min) | Course session or simulated play |

| Fri | Strength: upper & core (moderate) | Range: random practice + feedback (30-45 min) |

| Sat | Competition/play day or long game practice | Recovery + mobility |

| Sun | Rest or active recovery | Review data & plan for next week |

Benefits and practical tips

- Use data to set small, measurable goals (e.g., +1.5 mph clubhead speed in 8 weeks).

- Combine technical changes with strength/mobility work-body adaptations must precede consistent technical gains.

- Prioritize the short game and putting during limited practice time for faster score improvements.

- Log subjective fatigue; if HRV drops or soreness increases, favor technique and recovery over heavy loading.

Case study (practical example)

Golfer A (amateur, 15 handicap) had limited thoracic rotation and low rotational power. baseline testing: 94 mph driver speed and 0.9 smash factor, thoracic rotation 30° lead side. Intervention: 8 weeks of combined thoracic mobility work, med-ball rotational throws twice weekly, and strength session with single-leg focus. outcome: 5-7° gain in thoracic rotation, +4 mph driver speed, improved smash factor and 10-15 yard increase in carry on average. Subjectively, the golfer reported more consistent contact and less low-back soreness-demonstrating how targeted, evidence-based interventions translate to strokes saved.

First-hand coaching tips

- Start with a thorough assessment-don’t chase quick fixes.

- Use clear, measurable objectives and revisit them every 4 weeks.

- integrate short, high-quality training sessions into busy schedules; consistency beats intensity.

- Communicate numbers and progress to the player-objective feedback motivates and clarifies priorities.

Note on sources

The search results provided alongside this request returned unrelated media (comic-focused pages). The practical recommendations above reflect commonly accepted sports science, biomechanics, and strength & conditioning principles used by golf coaches and performance teams. For implementation, partner with a certified coach, physical therapist, or golf performance specialist who can individualize testing and programming.

Additional resources & next steps

- Schedule a baseline session with a launch monitor and movement screen.

- Track progress with a simple spreadsheet for swing speed, mobility degrees, and short game proximity-to-hole.

- Consider periodic retesting every 6-8 weeks to adapt your plan.