Golf demands both precise technique and robust physical capacity; small improvements in movement efficiency, force generation, and physiological durability often produce measurable gains on the course. Contemporary research increasingly frames golf performance as the outcome of interacting systems-biomechanical coordination, neuromuscular power, metabolic endurance and tissue resilience-rather than only skill or equipment. Therefore, training for golf should be evidence-informed and designed to translate from the gym or lab to on-course outcomes such as clubhead speed, shot dispersion, consistent movement patterns, and the ability to resist fatigue during 4-5 hour rounds.

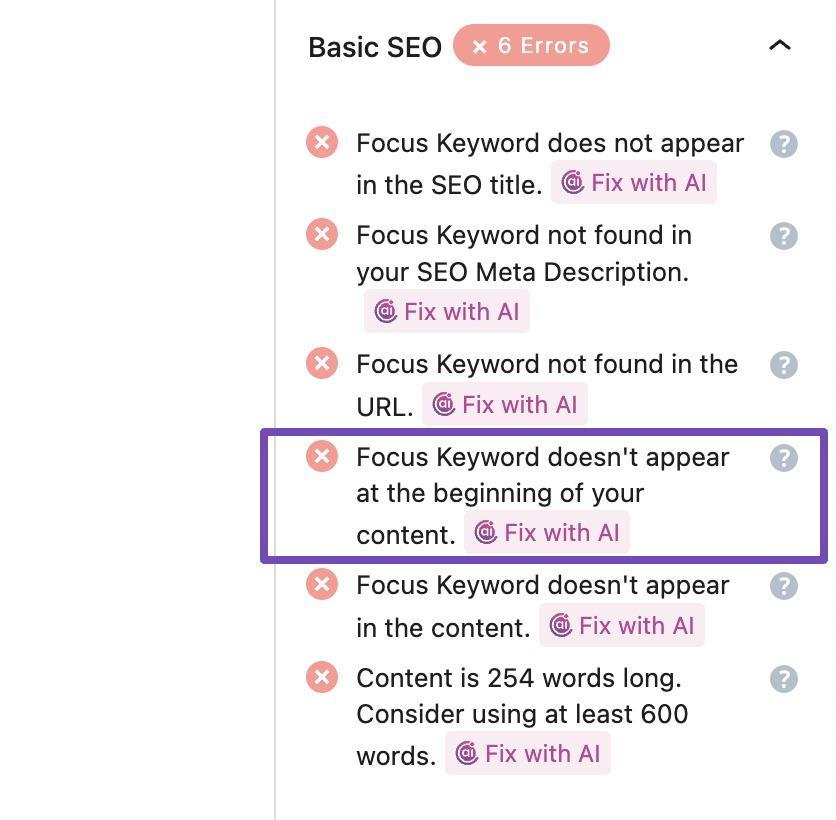

This article condenses current, research-aligned approaches to improving golf-specific fitness and on-course performance. Core themes are: thorough assessment and tailored programming; concurrent development of strength, power, rotational mobility and stability; specificity plus progressive overload to ensure transfer to the swing; and periodized planning to peak for competition. We also examine related areas-motor learning strategies that boost skill transfer, methods for load monitoring and outcome tracking (e.g., force-velocity profiling, ROM screens, swing kinetics/kinematics), and injury-mitigation tactics-to ensure programs are both effective and safe.

The intent is practical: offer coaches, strength & conditioning professionals, sports scientists and clinicians a usable, scientifically grounded framework to raise performance while reducing injury risk. By synthesizing intervention research with mechanistic understanding and pragmatic coaching constraints, the piece identifies fitness strategies most likely to produce meaningful, measurable improvements in golf and explains how to adapt them across ages, skill levels and competitive contexts.

Incorporating Biomechanical Testing to Personalize Swing Development

Objective biomechanical testing is the cornerstone of individualized swing and training plans. Quantifying kinematics (joint angles and angular velocities),kinetics (ground reaction forces and joint moments) and neuromuscular timing moves the practitioner beyond subjective observation to evidence-driven priorities. This data-driven baseline helps distinguish genuine performance constraints from stylistic variation, making interventions more precise and more likely to transfer to on-course outcomes.

A comprehensive evaluation synthesizes multiple tools to view the swing as an integrated movement. Common components are:

- 3D motion capture to quantify segment sequencing, X‑factor and peak angular velocities

- Force plates to measure ground-reaction patterns, impulse and weight-shift timing

- Range-of-motion and strength tests to identify joint-specific deficits

- EMG where available, to map activation timing across trunk and hips

Interpreting these outputs requires a framework that connects observed mechanics to training levers. For instance, diminished pelvis-to-shoulder separation or delayed proximal‑to‑distal transfer often indicates restricted rotational mobility or insufficient rate of force development (RFD); the corrective plan then targets mobility work and explosive rotational strength with golf-specific constraints. Emphasize specificity: exercises should reproduce relative timing and the planes of force production seen in the swing to maximize neuromuscular transfer.

| Typical Observation | Probable Cause | Recommended Intervention |

|---|---|---|

| Early lateral sway | Insufficient frontal-plane control | Single-leg stability drills + lateral bracing work |

| Low clubhead speed | Poor RFD or delayed sequencing | Rotational power complexes and targeted plyometrics |

| Restricted hip turn | Limited hip ROM or soft‑tissue constraint | Focused hip mobility work and soft-tissue techniques |

Regularly repeating biomechanical assessments during a planned intervention allows progressive overload,objective tracking and timely course corrections. Reassess at milestones (commonly every 6-12 weeks) and summarize changes in a compact performance dashboard tracking key indicators (e.g., peak angular velocity, sequencing lag, net impulse). Collaboration across disciplines-coach, S&C, physiotherapist and biomechanist-ensures prescriptions are practical, safe and aligned with competition plans.

Thoracic Rotation and Mobility: Unlocking Separation, Speed and Consistency

Thoracic rotation enables dissociation between pelvis and shoulders, allowing elastic energy storage and efficient transfer to the clubhead. When thoracic extension or rotational range is limited, golfers often compensate with excessive lumbar motion or shoulder adjustments, which reduce efficiency and raise injury risk. Multiple biomechanical studies associate improved thoracic mobility with greater angular separation, longer acceleration windows and decreased lateral bending-factors linked to increases in clubhead speed and improved shot repeatability.

Assessment must be reliable and golf-relevant.Combine lab-grade measures (3D capture or IMUs for rotational speed and separation) with practical field tests like seated thoracic rotation with an inclinometer, quadruped extension-rotation screening, and a standing reach/rotation test while holding the club. Key targets to quantify are:

- Active thoracic rotation (°)

- Thoracic extension range

- Rotation velocity

- Symmetry and provoked pain

Link deficits to swing mechanics to prioritize interventions.

Effective interventions are multimodal and staged. Manual techniques (thoracic mobilizations, instrument-assisted soft tissue work), progressive mobility drills (foam‑roller thoracic extensions, windmills) and neuromuscular re‑training (loaded rotational carries, band-resisted swing patterns) target tissue extensibility, joint mechanics and motor control. A practical dosing strategy begins with short daily mobility sessions (5-10 minutes) and advances to loaded rotational work 2-3×/week, progressing to speed and power challenges as control and tolerance improve.

Integrate thoracic work logically within S&C: restore extension/rotation before exposing the athlete to high-velocity swing mechanics,then combine thoracic mobility with hip mobility and rotational-power training. Sample focuses include:

- controlled thoracic extension progressions using a foam roller

- Rotational dissociation drills such as band-resisted half-swings

- Loaded rotational power (medicine‑ball throws)

Quality and symmetry trump raw range-excess passive motion without stability will not boost clubhead speed or consistency.

Track both clinical and performance outcomes: swing speed and dispersion metrics, thoracic ROM and rotation velocity, and patient-reported function or discomfort. Use objective progression criteria (for example, steady increases in peak rotation velocity or a 3-5 mph rise in swing speed) to advance load; regress when pain or compensatory movement returns.

| Exercise | Sets | Frequency |

|---|---|---|

| Thoracic foam-roll with active reaches | 3 | Daily |

| Band-resisted controlled rotation | 3-4 | 2-3×/week |

| Medicine ball rotational throw (progressive) | 4-6 | 1-2×/week |

Targeted Strength Work for Hips, Core and Scapular Control

Programming fundamentals for golf emphasize movement specificity, progressive overload, unilateral training bias and motor control under load. The objective is to enhance force transmission through the kinetic chain rather than merely increase muscle size. Training sessions therefore prioritize rate of force development, eccentric control and the timed sequencing of segments. Primary goals are:

- Increase hip rotational torque without sacrificing mobility;

- build core anti‑rotation and anti‑extension stability to support energy transfer;

- Refine scapular control so shoulder mechanics remain reliable during high‑velocity swings.

Hip training focuses on multiplanar strength and dynamic control.Progressions flow from isometrics and band-resisted patterns to loaded explosive variations such as glute-bridge → single-leg bridge, banded lateral walks, Bulgarian split squats, and single-leg Romanian deadlifts. Typical prescriptions: 2-3 sets of 6-12 reps during strength phases and 3-6 sets of 3-6 explosive reps (e.g., loaded jumps or med‑ball rotational throws) during power phases. Use tempo cues (e.g.,3-4 s eccentric) and insist on high-quality single‑leg stability to limit compensatory lumbar motion and improve pelvis-to-shaft force transfer.

Core training should emphasize anti‑rotation, anti‑extension and power transfer. Start with controlled isometrics (front and side planks) and progress to dynamic resisted patterns (Pallof press variations, cable chops, resisted band rotations). A practical weekly progression might include:

| Exercise | Progression | Sets × Reps |

|---|---|---|

| Pallof Press | Tall‑kneel → half‑kneel → split‑stance | 3 × 8-12 |

| Anti‑Extension Rollout | Knee → standing wheel | 3 × 6-10 |

| Med‑Ball Rotational Throw | seated → half‑knee → standing | 4 × 3-6 (power) |

Scapular stability must be treated both locally and as a link in the kinetic chain. Prioritize lower trapezius and serratus anterior activation via banded serratus punches, prone Y/T/L raises, face pulls with external rotation and quadrant rowing. Pair these with thoracic extension mobility so scapulothoracic rhythm occurs without compensatory neck or glenohumeral motion. Prescription: low to moderate load, 2-4 sets of 8-15 focused on controlled eccentric work to reduce impingement risk while increasing stroke stability.

Embed these modules into a periodized weekly structure tied to on-course practice and technical sessions: during the competitive season, maintain with two targeted strength sessions (hip/core) plus one upper-quarter stabilization workout per week; in the off‑season increase to three strength sessions and add power blocks. Monitor readiness with straightforward measures (single-leg balance time,median thoracic rotation,subjective RPE during swings) and prioritize recovery when control declines. Key implementation rules: train along the swingS force vectors, progress from static stability to dynamic rotational power, and frequently re-evaluate loads to avoid overload.

Building Rotational Speed and Power with Plyometrics and Medicine Ball Progressions

Rotational power in the swing emerges from coordinated neuromuscular strategies that leverage the stretch‑shortening cycle, proximal‑to‑distal sequencing and efficient ground‑force transfer. Plyometrics and medicine‑ball drills develop the elastic return and explosive torque needed for high clubhead velocity because they train rate-of-force development in golf‑specific planes. Training should target: (1) enhanced hip‑torso dissociation while maintaining pelvic control, (2) increased transverse‑plane impulse via lower-limb plyometrics, and (3) improved kinetic chain timing so peak angular velocity aligns with impact.

Medicine‑ball progressions should be methodical and technique-driven.Sample sequence-practiced until technical criteria are satisfied-includes:

- Seated chest pass (isolate upper‑body velocity)

- Seated rotational throw (trunk sequencing)

- Tall‑kneel rotational throw (anti‑extension, pelvic stability)

- Standing bilateral rotational throw (integrated hip drive)

- Step‑in / step‑through rotational throw (weight transfer and timing)

Progress from light, fast implements to heavier balls as neuromuscular control and velocity tolerate load; emphasize angular speed and technique over simply increasing mass to maximize swing transfer.

Plyometric progressions should emphasize lower‑extremity power and transverse reactivity to potentiate the chain. Useful drills include:

- Squat‑to‑rotational‑bound (vertical→rotational transfer)

- Unilateral lateral bounds (frontal/transverse force transfer)

- Crossover hops with brief ground contact (rapid decel‑reAccel)

- Reactive rotational med‑ball throws (develop reactive stiffness)

Choose variations with short contact times and safe landing mechanics,progressing from bilateral,low‑amplitude hops to more challenging unilateral and rotational tasks as capacity grows.

Structure programming with periodization: early stages emphasize motor learning and low-load, high‑velocity throws (e.g., 3-5 sets of 6-8 reps, 2-3×/week); intermediate phases add complexity and plyometrics (3-6 sets of 3-6 explosive reps, ~2×/week); peak phases merge heavier ballistic loads and sport-specific explosive throws in line with competition tapering.Rest sufficiently to preserve quality (60-120 s between ballistic sets; 2-3 min for maximal plyometrics). Avoid scheduling technical swing work immediately after power sessions unless the athlete demonstrates stable movement to prevent motor interference.

risk control and objective checks are critical: screen hips, trunk stability and single‑leg symmetry before progression and track performance indicators (med‑ball distance, peak angular velocity, CMJ asymmetry) to guide load. Regress or stop drills when technique degrades-loss of hip‑shoulder separation, excessive lumbar extension or valgus collapse are red flags. The table below gives a concise progression template with coaching cues and primary targets.

| Phase | Example Drill | Primary Cue |

|---|---|---|

| Foundation | Seated rotational pass | “Rapid trunk snap, maintain tall posture” |

| Transition | Tall‑kneel throws | “Keep pelvis stable, accelerate through chest” |

| Transfer | Step‑in rotational throw | “Drive the lead hip, rotate aggressively” |

Aerobic and Anaerobic Conditioning to Preserve Output and Decision Quality

Modern conditioning for golf treats aerobic and anaerobic fitness as complementary systems that sustain physical output and cognitive performance during multi‑hour rounds. Aerobic conditioning underpins baseline work capacity, thermoregulation and substrate delivery; anaerobic capacity enables short, high‑intensity actions (powerful swings, uphill walks, short sprints) and rapid recovery between those events.Positioning conditioning within a biopsychophysiological framework shows how targeted training diminishes peripheral and central fatigue, helping players make better decisions and execute under late‑round pressure.

Aerobic training offers benefits for sustained attention, executive function and mood-domains central to pre‑shot routines and strategic decisions. moderate-intensity continuous training (MICT) and longer low-intensity sessions increase mitochondrial density and autonomic balance, lowering perceived exertion and helping players maintain cognitive sharpness in heat or wind. Practically, golfers with higher VO2max and improved submaximal efficiency tend to show steadier club selection and fewer late‑round tactical errors.

anaerobic and high‑intensity work is equally important for golf-specific power and repeated maximal efforts. Short, near‑maximal intervals improve phosphagen and glycolytic capacity, supporting multiple explosive swings and quick positional adjustments. Effective anaerobic modalities include:

- Repeated sprint intervals (e.g., 6-10 × 10-20 s with full recovery)

- Short HIIT circuits combining rotational med‑ball throws and loaded carries

- Maximal power sets (trap bar jumps, derivatives of Olympic lifts) at low volume

Sequence these modalities to avoid interference with technical practice windows.

Combine modalities within a periodized microcycle that alternates aerobic base days with anaerobic and power sessions to protect technical quality and reduce overload. Below is a transferable microcycle template for a golfer preparing to compete; use HR zones and session RPE to individualize intensity and recovery needs.

| Session | Focus | Duration / Intensity |

|---|---|---|

| Day 1 | Aerobic steady state | 40-60 min @ ~60-70% HRmax |

| Day 2 | Power + technical work | 20-30 min power; 60-90 min swing practice |

| Day 3 | Anaerobic intervals | 15-25 min HIIT (work:rest ~1:3-1:5) |

Implement objective monitoring-heart rate zones, session RPE, HRV and short field tests (e.g., CMJ, 30‑s high‑effort analogues)-to guide training intensity and recovery. In‑season focus is maintenance of power and aerobic base at reduced volume with increased technical specificity; off‑season emphasis shifts to capacity building. Consistent recovery practices (sleep prioritization, periodized nutrition for glycogen and phosphagen replenishment) are crucial for converting conditioning adaptations into reliable on‑course decision‑making and execution.

Neuromotor Training to Create Repeatable, Robust Swing Patterns

Shot‑to‑shot consistency depends on the nervous system forming stable sensorimotor mappings that generalize across variable contexts. Recent work shows that repeatable kinematics come from reliable feedforward motor programs complemented by context‑sensitive feedback corrections. Strengthening these programs requires training intersegmental timing, force sequencing and muscular synergies so players can produce consistent clubhead outcomes with less conscious control. In practice, interventions should link task goals to motor commands to reduce unwanted variability in key swing metrics.

Retraining rests on a few evidence-backed principles: specificity, progressive challenge and managed variability. Translate these into concrete training targets:

- Proprioceptive acuity – drills that sharpen body awareness (e.g., blind‑feel half‑swings)

- Temporal sequencing – exercises emphasizing pelvis→thorax timing and distal acceleration

- Force demands – loaded/unloaded swings to develop lower‑limb RFD

- contextual variability – controlled perturbations to build adaptable motor programs

Integrate these progressively and use objective metrics to guide progression.

Feedback strategy strongly affects retention and transfer. Meta-analyses favor an external focus (e.g., target or ball‑path cues) to promote automaticity, and suggest fading augmented feedback to foster self‑monitoring. Apply low-frequency summary feedback, bandwidth schedules and intermittent biofeedback (EMG or IMUs) to speed calibration without creating reliance. Clinicians can use EMG to refine trunk and hip timing; coaches can emphasize shot outcomes and kinematic snapshots to reinforce effective solutions rather than micromanaging individual muscles.

Adopt a constraint‑led approach in drills-manipulating task, habitat or performer constraints to elicit desired coordination. Examples: tempo‑limited swings to stabilize timing, single‑leg address to emphasize lower‑limb drive, randomized club order to enhance adaptability. Progress from blocked, repetitive practice to variable practice phases to move from acquisition to robustness. Combine neuromuscular conditioning that favors rapid eccentric‑concentric transitions and intermuscular coordination over isolated strength work.

Embed simple,repeatable monitoring within training to track both performance and injury risk. Portable sensors make this feasible. Priorities include:

| Metric | Target | meaning |

|---|---|---|

| Pelvis‑thorax separation (°) | Consistent ±3° | Reflects X‑factor timing; high variability indicates sequencing faults |

| Clubhead speed CV (%) | <4% | Consistency of power output and neuromuscular control |

| EMG onset latency (ms) | Stable within session | Shows anticipatory activation; asymmetry could signal overload |

Use these metrics to pace progressive overload, detect maladaptive compensations and prescribe targeted neuromuscular strategies that enhance both repeatability and tissue resilience.

Reducing injury Risk by Building Tissue Capacity with Gradual Load

Evidence supports a graded approach to increasing musculoskeletal tolerance to golf’s multi‑planar demands. Rather than seeking to eliminate all discomfort, planned and incremental mechanical stress encourages adaptive responses in muscle, tendon, ligament and bone-lowering the chance of acute overload and long‑term degeneration. physiological adaptations of interest include tendon collagen remodeling, bone remodeling, increases in muscle cross‑section and improved neuromuscular coordination; these occur when load is applied within a controlled framework that balances stimulus and recovery. Program selection should mirror swing‑specific velocities, force paths and repeated submaximal loading patterns.

Implementation requires manipulation of primary load drivers and constant monitoring of internal response. Core variables to manage are:

- Intensity (force/resistance per rep)

- Volume (total reps, sets or cumulative work)

- frequency (how often stress is applied)

- Complexity / Speed (movement control, velocity, coordination)

Sequence these variables to first build tissue tolerance (moderate intensity, higher controlled volume), then develop strength (higher intensity, lower volume) and finally integrate speed and power. Throughout, objective and subjective monitoring should guide dose adjustments to mitigate injury risk.

| Phase | Main Aim | Representative Session |

|---|---|---|

| 1 – Capacity | Raise baseline tolerance | 3 × 12-15 controlled RDLs and anti‑rotation holds |

| 2 – Strength | Increase maximal force | 4 × 4-6 heavy rows,single‑leg squats |

| 3 – Power | Convert strength to speed | 6 × med‑ball rotational throws and jump‑splits |

| 4 – Maintenance | Sustain capacity during play | Mixed plan: 2 strength + 1 power sessions weekly |

Conservative progression is vital. Use metrics like session RPE, movement velocity (if available), objective load (kg × reps) and validated patient‑reported outcomes to guide increases. Make progression criteria explicit (e.g., two consecutive sessions with no pain increase and improved performance markers) and predefined regression rules (e.g.,persistent pain >24-48 hours,neurogenic signs). Screen for contraindications-unremitting lumbar pain,radiculopathy or spinal stenosis-and obtain medical clearance before initiating high‑velocity rotational training.

Tendon health responds well to staged loading: begin with isometric holds, progress to slow eccentrics then to faster concentric work. Improving local muscular endurance reduces fatigue‑related technique breakdown that can precipitate injury,while movement quality drills protect lumbopelvic control under load. Conservative increment strategies (commonly 5-15% weekly increases individualized to the athlete) and purposeful variation in loading patterns limit repetitive microtrauma. Add prehab routines, scheduled deloads and on‑course load management to build a resilient, evidence‑based model for long‑term performance.

Monitoring, Periodization and Criterion‑Driven Progressions for Lasting Gains

Systematic monitoring underpins informed training decisions. Combine baseline and serial assessments that include swing metrics (clubhead speed, ball speed, spin), movement screens (thoracic and hip rotation), neuromuscular tests (countermovement jump, isometric mid‑thigh pull) and psychophysiological markers (HRV, session RPE). Use both lab tools (3D capture,force plates) and field devices (launch monitors,wearables) to triangulate signals and reduce overreliance on single measures. Define minimal detectable change for each metric to seperate real adaptation from measurement noise.

Periodize training around plausible biological sequencing and the competition calendar. Structure macro‑, meso‑ and micro‑cycles to progress from capacity (hypertrophy) → maximal strength → power, and include planned recovery blocks and peaking strategies.Evidence supports block periodization for neuromuscular targets and tactical tapering to sharpen readiness. Always follow the principles of progressive overload, specificity and individualization, and protect gains through maintenance phases against reversibility.

Progress based on criteria rather than preset timelines.Use objective thresholds and autoregulation to scale load and complexity. Key advancement cues include improved test scores, retained movement quality, athlete readiness and absence of pain. Recommended methods are:

- Objective thresholds: progress when tests exceed pre‑persistent minimal detectable changes

- Autoregulation: adjust using session RPE, bar velocity or readiness indices

- Movement-first approach: prioritize technical fidelity; regress if compensations appear

Convert monitoring outputs into simple, actionable rules in a clinician‑coach dashboard. Examples:

| Metric | trigger | Suggested Action |

|---|---|---|

| HRV ↓ 10% from baseline | Sign of autonomic stress | Lower intensity; recovery interventions |

| CMJ ↓ 5% | Neuromuscular fatigue | Postpone heavy power; use submaximal work |

| Strength test betterment | Sustained force gains | Move to a power‑focused block |

For long‑term success, embed monitoring and periodization within a multidisciplinary system that stresses athlete education, careful load management and incremental progression. Maximize transfer by aligning S&C objectives with swing biomechanics and course demands, and routinely revisit the periodized plan considering competition outcomes and health status. Core takeaways: use criterion‑based progression, combine objective and subjective monitoring, and keep periodization flexible so the athlete remains healthy and peaks when it matters most.

Q&A

Q1: What does “evidence‑based golf fitness and performance” mean?

A1: Evidence‑based golf fitness applies findings from biomechanics, exercise physiology, sports science and clinical research to the assessment, prescription and monitoring of training programs aimed at improving swing mechanics, increasing power and clubhead speed, enhancing on‑course performance and minimizing injury risk. It prioritizes objective testing, interventions with demonstrated efficacy and ongoing measurement to confirm transfer to golf outcomes.

Q2: What forms of evidence are relevant and how should quality be judged?

A2: Useful evidence spans randomized controlled trials, controlled cohorts, cross‑sectional and longitudinal observational studies, biomechanics lab experiments and systematic reviews/meta‑analyses. Quality appraisal should take into account study design, participant characteristics (skill, age), ecological validity (lab vs on‑course), effect sizes, statistical power and replication.Because the golf literature can be heterogeneous and sometimes small, practitioners must weigh evidence strength alongside clinical judgment and player preferences.

Q3: Which physical traits most strongly predict golf performance?

A3: Converging data indicate rotational power and velocity (trunk and hip rotation),lower‑body force output and rate of force development (RFD) are central to clubhead and ball speed. Mobility (thoracic spine and hips), core stability and balance support efficient mechanics and injury prevention. Aerobic capacity is less directly linked to shot metrics but contributes importantly to recovery and sustained performance across rounds.Q4: Which assessments are recommended to identify deficits and monitor progress?

A4: A broad assessment battery typically includes:

– Golf‑specific metrics: clubhead speed, ball speed and launch‑monitor outputs (carry, spin).

– Movement and mobility screens: thoracic rotation,hip internal/external rotation,single‑leg balance,ankle dorsiflexion.

– Strength and power tests: isometric mid‑thigh pull or hip thrusts, countermovement jump, medicine‑ball rotational throws and RFD measures where possible.

– Injury screening: lumbar and shoulder assessments, swing kinematic review.

– Ongoing monitoring: session RPE, wellness forms and training load logs.

Repeat tests at planned intervals (commonly 6-12 weeks) to track adaptation.

Q5: What training principles should steer program design?

A5: Emphasize specificity (matching movements, speeds and force qualities to the swing), progressive overload, individualization (based on testing), periodization (staged variation across phases), recovery management and multimodal integration (strength, power, mobility, stability, conditioning). Ensure training emphasizes transfer with golf‑relevant patterns and velocities.

Q6: Which exercises and tools have support for improving golf power and speed?

A6: Supported choices include:

– Strength: compound posterior‑chain lifts (deadlifts,squats,hip thrusts).

– Power: ballistic and rotational drills (medicine‑ball rotational throws, rotational slams, jump squats, kettlebell swings).

– Core/anti‑rotation work: Pallof presses, progressive chops/lifts.

– Unilateral stability: single‑leg RDLs and step‑downs.

– Mobility: thoracic and hip mobility sequences.

Progress from slower strength foundations to high‑velocity power work to optimize RFD and speed transfer to the swing.Q7: How should training be periodized through a season?

A7: A practical plan:

– Off‑season: fix deficits and build strength (higher volume, lower velocity).

– Pre‑competition: transition to strength‑speed and high‑velocity, golf‑specific transfer drills (moderate volume, higher speed).

- In‑season: maintain strength and power at reduced volume,emphasize specificity and tapering for key events.include routine deloads and adjust load based on fatigue and readiness.

Q8: How do you ensure gym gains carry over to the golf swing?

A8: Maximize transfer by:

– Training at swing‑relevant velocities and movement patterns (rotational, unilateral).

– Progressing from general strength to speed‑strength and ballistic work.

– Pairing power sets with immediate technical swings to reinforce transfer.

- Tracking objective swing metrics (clubhead speed, ball speed).

– coordinating closely with the technical coach to embed physical gains into the motor program.Q9: What are common golf injuries and prevention strategies?

A9: Frequent issues include low‑back pain, wrist/elbow overuse and shoulder strains. Prevention strategies with rationale (and some empirical support) include:

– Improving thoracic and hip mobility to reduce compensatory lumbar rotation.

– Strengthening posterior chain and core to manage forces.

– Gradual load progression for practice and training.

– Technique adjustments to lower harmful stressors.

– Targeted prehab for previously injured areas.

Regular screening and individualized plans reduce both incidence and severity.

Q10: What monitoring approaches and outcome metrics should be used?

A10: Adopt multimodal monitoring:

– Performance: clubhead speed, ball speed, carry distance (launch monitors).

– Neuromuscular/physiological: CMJ, RFD tests, force‑plate outputs.

– Subjective: session RPE,wellness and sleep/fatigue logs.

– Training load: sRPE × duration, GPS/accelerometry for on‑course work if applicable.

– Re‑test regularly (e.g.,every 6-12 weeks) to guide adjustments.

Q11: How do amateur and elite programs differ?

A11: Elite players demand:

– Highly individualized, tech‑assisted monitoring and marginal gains work.

– More aggressive power development and precision tapering.

– Full multidisciplinary support (coach,S&C,sports medicine,biomechanist).

Amateurs usually benefit most from addressing fundamental deficits (mobility, strength) via time‑efficient programs with clear progression rules. Both groups need consistent long‑term development.

Q12: What role does technology play and what are its limits?

A12: Useful tools: launch monitors, 3D capture and IMUs, force plates, wearable sensors and video analysis. Limitations include cost,need for expert interpretation,risk of overreliance on lab data without proven on‑course transfer and measurement noise. Technology should augment, not replace, sound coaching and clinical judgment.

Q13: What are critically important research gaps?

A13: Key gaps are the scarcity of large randomized, long‑term trials that directly link specific physical interventions to on‑course outcomes, limited ecological validity in some lab metrics, heterogeneity in participant profiles and insufficient precision data on which subgroups benefit most. Future work should prioritize longitudinal, ecologically valid studies and personalized response analyses.

Q14: What immediate, practical steps can coaches and clinicians take?

A14: quick actions:

1. Conduct baseline testing to find the largest performance gaps (rotational power, thoracic mobility, hip function).2. Address those deficits with a staged strength‑then‑power progression.

3. Insert golf‑specific,high‑velocity drills and follow with technical swing work to consolidate transfer.

4. Monitor objective metrics and subjective readiness; adjust load when signs of fatigue appear.5. Coordinate with technical coaches and medical staff and embed recovery and prehab processes.

Q15: How should authors use “evidence” and related terminology in academic writing?

A15: Use precise academic phrasing: treat “evidence” as an uncountable noun-say “more evidence,” “further evidence” or “pieces of evidence” rather than “an evidence.” For causal or descriptive constructions prefer “as evidenced by” or “evidenced in/by.” Use “proof of concept” appropriately as a noun or modifier. Attention to these conventions improves clarity and professionalism in academic texts.Note: The earlier web results consulted concerned English usage of “evidence”; they informed the guidance in Q15 but are not substantive sources for the sport‑science content above.

References and further reading (selective):

– Recent systematic reviews and meta‑analyses in sport biomechanics and exercise physiology on rotational power, RFD and transfer to sport.

– Practitioner texts on periodization and S&C for rotational sports.

– Technical guides for launch monitor interpretation and biomechanical assessment.

If useful,I can convert this Q&A into a formatted FAQ for publication,produce tailored sample programs for male and female amateur golfers,or draft a condensed literature summary with citations to primary studies.

Key Takeaways and Final Thoughts

this synthesis integrates biomechanical, physiological and training literature into a practical, evidence‑oriented approach to golf fitness and injury prevention.Main conclusions are: (1) objective, golf‑specific measurement of mobility, strength, power and neuromuscular control should drive individualized programming; (2) periodized approaches that blend movement quality, strength/power and task‑specific transfer to the swing deliver the most consistent gains; (3) workload monitoring, screening and targeted prehabilitation reduce injury risk when implemented over time; and (4) combining laboratory and field metrics provides meaningful monitoring and guides progression.

For practitioners and researchers,these recommendations underline a collaborative,evidence‑informed model: perform comprehensive baseline testing,prioritize corrective strength and power work mapped to swing demands,use objective monitoring to guide progression and recovery,and synchronize conditioning with technical training and competition calendars. Tailor implementation to player age, injury history, competitive level and resource access.

Limitations of the evidence base include varied outcome measures, modest sample sizes in some intervention trials and limited long‑term transfer data to tournament play. Future research should emphasize randomized longitudinal trials with ecologically valid endpoints, mechanistic links between physiological adaptation and ball/swing outcomes, and multidisciplinary studies crossing biomechanics, motor learning and sports medicine. Adopting an evidence‑led, collaborative approach-where coaches, S&C professionals, physiotherapists and biomechanists share data and priorities-offers the best route to sustainable performance improvements while minimizing injury risk. (Language note: in academic contexts, treat ”evidence” as a non‑count noun; prefer formulations like “more evidence” or “further evidence” for clarity.)

The Golf Fitness Blueprint: Science-Proven Strategies for Power, Precision, and Durability

Pick a tone: scientific, bold, practical, or playful – this article uses a practical-scientific voice to translate biomechanics and exercise science into targeted golf fitness programming. Below you’ll find movement priorities, assessments, evidence-informed exercise selection, weekly templates, and injury-prevention strategies to boost clubhead speed, improve consistency, and keep you playing more rounds.

Why golf fitness matters (keywords: golf fitness, clubhead speed, swing mechanics)

Modern golf performance is driven by more than technique: swing mechanics, kinetic sequencing, and physical capacity interact to produce distance and accuracy. Improving mobility,stability,strength,and rotational power increases clubhead speed,optimizes energy transfer through the kinetic chain,and reduces injury risk-especially to the lower back,shoulder,and elbow.

Core biomechanical and physiological principles

- Kinetic sequencing: Efficient force transfer starts with ground reaction force through the legs and hips, through trunk rotation, and finaly to the arms and club. Timing (sequencing) is as vital as raw strength.

- Rotational power: Golf requires rapid axial rotation and the ability to decelerate-develop both explosive rotational output (med-ball throws) and eccentric control (reverse-lunge decels).

- Mobility-stability balance: Good hip internal/external rotation and thoracic rotation allow freedom of movement while lumbar stability prevents excessive shear and extension forces that commonly cause low-back pain.

- Energy system demands: Golf is low-intensity for long durations with short bursts of high-intensity efforts (swing).Prioritize aerobic conditioning for recovery and short high-intensity work for power and recovery between holes.

Assessment & screening (keywords: golf screening, movement screens)

Start every training plan with an assessment to prioritize deficits:

- Single-leg balance (30s eyes open -> closed)

- Single-leg squat or step-down quality

- Thoracic rotation ROM (seated/standing)

- Hip internal/external rotation and straight-leg raise

- Overhead reach and shoulder external rotation strength

- Medicine ball rotational throw distance or speed (simple measure of rotational power)

- Clubhead speed baseline (launch monitor or radar)

Mobility & stability priorities (keywords: thoracic rotation, hip mobility, core stability)

Targeted mobility and stability improve swing position and reduce compensatory stresses.

Key mobility targets

- thoracic rotation: seated thoracic windmills, foam-roll thoracic extensions (2-3 sets of 8-12 reps)

- Hip internal rotation: 90/90 drills, half-kneeling internal rotation (2-3 sets of 8-12 reps per side)

- Ankle dorsiflexion: calf-wall mobilizations (2-3 sets of 10-15 reps)

Key stability targets

- Anti-rotation core (Pallof press) 3-4 sets of 8-12s hold or 6-10 reps

- Single-leg balance and strength (single-leg RDL, single-leg squats) 3-4 sets of 6-10 reps

- Shoulder/scapular stability (banded external rotation, Y/T raises) 2-3 sets of 12-20 reps

Strength and power progress (keywords: golf strength, rotational power, medicine ball)

Train both maximal strength and power. Strength provides the foundation; power converts strength into clubhead speed.

Strength principles

- Compound lifts: deadlift/hip hinge, squat or split-squat, bent-over row, and push patterns-focus on 3-5 sets of 4-8 reps for strength.

- Unilateral work: single-leg RDLs, Bulgarian split squats-improves balance and reduces injury risk.

- Progressive overload: increase load, volume, or complexity over weeks.

Power principles

- Rotational med-ball throws (chest pass rotation,scoop toss) 3-5 sets of 4-8 reps for speed

- Olympic-variation power (if trained): hang cleans,kettlebell swings-3-5 sets of 3-6 reps

- Contrast training: heavy strength set followed by explosive throw or jump to potentiate power

Conditioning and on-course energy systems (keywords: golf conditioning,endurance)

Golfers benefit from an aerobic base to maintain focus and reduce fatigue,with intermittent high-intensity efforts to preserve short-burst power for swings.

- Aerobic: 2 sessions of 20-40 minutes moderate-intensity cardio per week (brisk walking,cycling)

- High-intensity intervals: 1 session weekly (e.g., 30s on/60s off x 8-10) to support recovery between shots and short-term power

- On-course walking practise with controlled carrying/carrying the bag to simulate load

Program templates: Beginner, Intermediate, Advanced (keywords: golf workout, weekly golf plan)

| Level | Sessions/Week | Focus | Example Session Mix |

|---|---|---|---|

| Beginner | 2-3 | Mobility + foundational strength | Full-body strength, mobility circuit, short walk |

| Intermediate | 3-4 | Strength + basic power | 3 gym days (strength+power), 1 cardio, 1 mobility |

| Advanced | 4-6 | max strength, advanced power, load management | periodized strength, power days, sport-specific conditioning |

Sample weekly plan (Intermediate)

- Monday - Strength (Lower biased): deadlift variations, split squats, core anti-rotation

- Tuesday - Mobility + short walk or on-course practice

- Wednesday – Power & Upper Strength: med-ball rotational throws, push/pull, rotator cuff work

- Thursday – Conditioning: aerobic 30-40 min or HIIT intervals

- Friday – Strength (Full body): squats, hip hinge, single-leg work, core

- Saturday – On-course practice + mobility warm-up

- Sunday – Active recovery: mobility, foam rolling, light swim/walk

Warm-up and pre-round routine (keywords: golf warm-up, pre-shot routine)

A dynamic, golf-specific warm-up primes mobility, activation and neuromuscular timing:

- 5-8 minutes light aerobic (brisk walk or bike)

- Dynamic mobility circuit: hip circles, thoracic rotations, leg swings (2 sets 8-10 each)

- Activation: glute bridges, banded lateral walks, Pallof press (2-3 sets)

- Progressive swings: half swings -> 3/4 swings -> full swings with short irons to driver

Injury prevention & load management (keywords: golf injury prevention, low-back pain)

Common golf injuries include lumbar spine issues, rotator cuff strain, medial epicondylitis, and knee pain. Reduce risk by:

- Maintaining hip and thoracic mobility to avoid lumbopelvic compensation

- Strengthening glutes and posterior chain to manage ground forces

- Progressing swing volume slowly (introduce range time before tournament weeks)

- including regular rotator cuff and scapular stabilization work

- Monitoring pain and using the 10-20% rule for weekly load increases

rehab-minded exercises to protect the low back and shoulder

- Bird-dog progressions for lumbar stability 2-3 sets of 8-12

- Pallof press anti-rotation 3-4 sets of 6-10 reps

- Band external rotation 3 sets of 12-20

Practical tips for translating training to the course (keywords: golf training tips)

- Train rotational speed, not just range of motion. Power is speed x mass-improve both.

- Integrate golf-specific drills: hit balls after a power set to train sequencing under fatigue.

- Practice walking the course with your gear to reproduce on-course energy demands.

- Use baseline metrics-clubhead speed, med-ball distance, single-leg balance-to track progress.

- Periodize your training: heavier strength phases in the off-season, power/peaking closer to competition.

Case study: 12-week example (first-hand style)

Golfer A (handicap 12) tested with a clubhead speed of 92 mph and poor thoracic rotation. A 12-week program focused on thoracic mobility, unilateral lower-body strength, and rotational power produced measurable change: +6 mph clubhead speed, improved ball speed and more consistent contact. Key elements: 2×/week med-ball throws, 3 weeks progressive deadlift loading, and ongoing thoracic mobility twice weekly. This combination improved sequencing-hip drive first, stable core, then arm/club acceleration-demonstrating how targeted physical training converts to on-course results.

Exercise examples with sets/reps (keywords: golf exercises)

- Romanian Deadlift (RDL): 3-5 sets x 4-8 reps – builds posterior chain strength for ground force production

- Banded Pallof press: 3-4 sets x 8-10 reps – anti-rotation core stability

- Med-ball Rotational Throw (standing): 3-5 sets x 4-8 reps – rotational power and rate of force development

- Single-leg RDL: 3 sets x 6-10 reps – unilateral strength and balance

- Thoracic Windmill: 2-3 sets x 8-12 reps – thoracic mobility for better turn

- Kettlebell Swing: 3-4 sets x 6-12 reps – explosive hip extension, posterior chain power

Measuring progress and KPIs (keywords: golf metrics, clubhead speed tracking)

Track simple KPIs to ensure training is transferring to the course:

- Clubhead speed and ball speed (launch monitor)

- Med-ball rotational throw distance or speed

- Single-leg balance time and single-leg squat depth/quality

- Deadlift or hinge strength (1-5RM progressions)

- On-course outcomes: fairways hit, greens in regulation, average driving distance

FAQ: Quick answers to common golf fitness questions

How often should I train?

For most golfers: 3 strength/power sessions per week with 1-2 mobility/conditioning sessions produces measurable gains. Adjust based on schedule and recovery.

Will strength training hurt my swing mechanics?

Not if programmed correctly.Strength training should improve swing durability and power-avoid excessive hypertrophy-only phases close to competition; emphasize power and mobility as you peak.

When will I see results?

Initial neuromuscular gains can appear in 4-6 weeks; meaningful increases in strength and clubhead speed often appear in 8-12 weeks with consistent training.

Additional resources and next steps (keywords: golf training resources)

- Start with a movement screen and baseline clubhead speed measurement.

- Use the sample weekly plans above and progressively overload strength and power elements.

- Prioritize recovery: sleep, nutrition (protein to support repair), and joint recovery strategies.

- Consider working with a certified golf fitness professional or strength coach who understands swing biomechanics for personalized programming.

If you want a variation with a playful or more scientific tone, or a condensed “quick-start” 4-week plan, tell me which tone you prefer and I’ll create a tailored version with printable workouts and a warm-up video checklist.