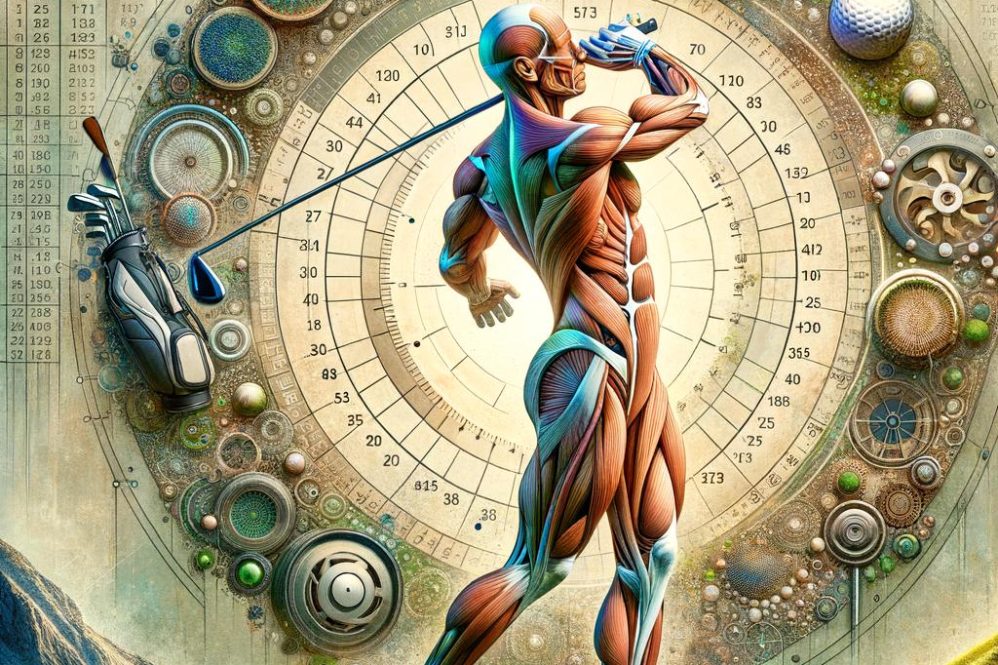

Integrative Golf Fitness: Biomechanics and Conditioning

Introduction

The term “integrative” connotes the deliberate combination of multiple disciplines or modalities to produce more effective outcomes (cambridge English Dictionary) [1]. Applied to golf performance,an integrative approach synthesizes biomechanical analysis,exercise physiology,and targeted conditioning into a unified framework designed to optimize swing efficiency,augment power production,and reduce injury risk. This multidisciplinary outlook mirrors contemporary trends in health care and performance practice that emphasize individualized, evidence‑based, and holistic strategies for improving function and resilience (Integrative Health and Wellbeing programs) [3].

Golf performance emerges from the interaction of movement mechanics, neuromuscular capacity, and physiological readiness. Biomechanics provides a quantitative description of the kinematic and kinetic patterns that underlie an efficient and repeatable swing; exercise physiology and strength‑and‑conditioning principles identify the physical capacities (strength, power, mobility, stability, and metabolic endurance) that enable those patterns to be produced and sustained. An integrative model thus moves beyond isolated interventions-such as technique coaching alone or strength training without movement specificity-to coordinate assessment,prescription,and progressive training that respect both the mechanical demands of the sport and the individual athlete’s physiological profile.

This article reviews current evidence linking swing biomechanics to performance and injury, synthesizes key physiological determinants of golf performance, and proposes a practical framework for integrating biomechanical assessment with conditioning interventions. Emphasis is placed on objective assessment, individualized program design, periodization, and measurable outcome metrics so that practitioners-coaches, physical therapists, and strength and conditioning professionals-can translate theory into effective, safe, and evidence‑informed practice.

Principles of Golf Biomechanics: Kinematic Sequencing and energy Transfer

Kinematic sequencing in the golf swing is characterized by a proximal-to-distal cascade of peak segmental angular velocities that maximizes energy transfer to the clubhead. In skilled performers the pelvis reaches peak angular velocity first, followed by the thorax, than the lead arm and finally the club – a temporal pattern that minimizes intersegmental counter‑torques and optimizes resultant clubhead speed. This ordered timing leverages intersegmental dynamics and the stretch‑shortening behavior of musculotendinous units to amplify output without commensurate increases in metabolic or joint loading.

From a kinetic perspective, effective energy transfer depends on coordinated production and redirection of forces rather than isolated power at a single joint. Ground reaction forces generate a base torque that is sequenced through the lower limbs and pelvis into the trunk; angular momentum is conserved and modulated by controlled deceleration of proximal segments to accelerate distal segments. Understanding the interplay of torque, moment arms and segmental inertia clarifies why improvements in mobility or strength alone will not translate to performance gains unless timing and intersegmental coordination are preserved.

Neuromuscular control defines the reproducibility of the kinematic chain and the resilience of that chain under competitive stress. Key measurable indicators for both assessment and training include:

- Pelvis peak velocity timing – temporal lead relative to thorax

- Trunk‑pelvis separation angle – magnitude and rate of separation

- Lead arm and wrist lag – maintained torque and delayed release

- Clubhead acceleration window – rapid distal acceleration with minimal proximal reversal

Imbalanced sequencing elevates localized load and predisposes the athlete to overuse injury, particularly in the lumbar spine and glenohumeral complex. The following table summarizes primary downswing phases, the essential mechanical action, and targeted conditioning priorities to preserve both performance and tissue tolerance.

| Phase | Key Action | Training Focus |

|---|---|---|

| Transition | Weight transfer & pelvic acceleration | Single‑leg strength,eccentric control |

| Downswing | Sequential trunk rotation & arm lag | Rotational power,motor timing drills |

| Impact | Rapid distal release & deceleration | Forearm eccentric tolerance,plyometrics |

Translating biomechanical principles into programming requires integrated,task‑specific exercises that preserve the kinematic sequence while enhancing capacity. Effective modalities emphasize coordinated multi‑segment actions, reactive stiffness and reliable timing rather than isolated hypertrophy. Examples include:

- Rotational medicine‑ball throws – reproducible proximal‑to‑distal timing under load

- Single‑leg Romanian deadlifts – force transfer through the kinetic chain

- Anti‑rotation pallof presses – trunk stiffness and deceleration control

- Cable wood‑chops with cadence constraints – refined sequencing and tempo

Functional Movement assessment for Golfers: Screening Protocols and Objective Metrics

Functional evaluation in golf should prioritize the translation of clinical findings to swing mechanics and on-course performance.Assessments are designed to detect deficits in **rotational mobility**, **symmetric force production**, dynamic balance and movement sequencing that are mechanistically linked to swing variability and injury risk. A defensible screening strategy balances sensitivity for dysfunction with specificity for golf-specific impairments, using standardized protocols that permit longitudinal comparison and multidisciplinary interaction.

Recommended batteries combine established clinical screens with sport-specific tasks. Core components include:

- Mobility: thoracic rotation, hip internal/external rotation, ankle dorsiflexion;

- Stability and motor control: single-leg stance with perturbation, prone bridge timing;

- Dynamic balance: Y-Balance Test (reach asymmetry and composite score);

- Power and speed: countermovement jump metrics and clubhead-speed-linked sprints or med-ball rotational throws.

Each element should be performed with standardized warm-up and clear, reproducible instructions to reduce measurement error.

Objective measurement enhances clinical decision-making. Use calibrated tools where feasible: **digital goniometers** for ROM (degrees), **force plates** for ground reaction force and rate of force growth (N, N·s⁻¹), **inertial measurement units (IMUs)** or 3D motion capture for segmental angular velocity (deg·s⁻¹) and sequencing, and validated smartphone apps for clubhead speed and swing tempo. Report metrics with reliability indices (ICC,SEM) and document limb-to-limb asymmetry,absolute values,and task-specific normative comparisons.

| Test | Primary metric | Concerning Threshold |

|---|---|---|

| thoracic Rotation | Degrees (max rotation) | <35° or >15% asymmetry |

| Y-Balance Composite | Composite (% leg length) | <94% or >4 cm asymmetry |

| Countermovement Jump | Peak Power (W·kg⁻¹) | Decrease >10% vs. baseline |

| Single-Leg Stance | Hold time (s) / COP excursion | <20 s or >10% asymmetry |

Screen findings must directly inform periodized interventions and reassessment cadence. Prioritize corrective strategies that address the highest-risk deficits (e.g., targeted thoracic mobility drills, hip external rotator strengthening, neuromuscular single-leg stability progressions) and integrate them with swing-focused training.Re-evaluate objective metrics at predefined intervals (commonly 6-12 weeks) and after any change in symptoms; adjust training load based on validated thresholds, documented asymmetries, and improvements in both clinical measures and performance outcomes such as clubhead speed and shot dispersion.

Strength and Power Conditioning for the Golf Swing: Targeted Exercises and Progressive Overload

Effective conditioning for the golf swing rests on three biomechanical foundations: specificity of movement, rate of force development, and the controlled application of progressive overload.Specificity means selecting exercises that reproduce the rotational, anti-rotational and single‑leg demands of the swing. Rate of force development (RFD) emphasizes brief, high‑velocity contractions to convert strength into swing speed. Progressive overload must be periodized so increased load, velocity or complexity is applied systematically while preserving swing mechanics.

Targeted exercise selection prioritizes integrated multi‑joint movements and unilateral work that mirror on‑course dynamics. Typical building blocks include:

- Rotational medicine ball throws – high velocity, low load to train RFD in the transverse plane;

- Single‑leg romanian deadlifts – stability and posterior chain control for weight transfer;

- Barbell deadlifts and hip thrusts – posterior chain strength to support powerful extension;

- Pallof presses and cable anti‑rotation – core stiffness against torsion during transition phases.

These are integrated with mobility and reactive drills to maximize transfer to the swing.

Programming follows a phased model that moves from capacity to expression. A concise table below outlines a pragmatic three‑phase progression used in applied settings:

| Phase | Focus | Typical sets × Reps / Intensity |

|---|---|---|

| Foundation | Hypertrophy & movement quality | 3-4×8-12 / 60-75% 1RM |

| Strength | Max force & stability | 3-5×3-6 / 80-90% 1RM |

| Power | RFD & velocity transfer | 4-6×2-5 (explosive) / 30-60% 1RM or bodyweight |

Monitoring and progressive overload require objective and subjective measures. Use swing speed,bar or ball velocity,and load progression as primary metrics; supplement with RPE and movement quality screens to avoid technique degradation. incremental increases in load, volume or movement complexity should be planned every 2-6 weeks depending on the athlete’s training age and fatigue markers.

Long‑term transfer and injury risk mitigation depend on deliberate integration with on‑course practice. Prioritize thoracic rotation, hip mobility and posterior chain durability in warmups, and program deload weeks and active recovery after intense phases. When implemented with clear progression and robust monitoring, this targeted conditioning model increases clubhead speed, improves consistency of contact, and reduces the incidence of overload injuries common to golfers.

Joint Mobility and Segmental Stability interventions for Optimal Swing Mechanics

Effective intervention prioritizes the dynamic relationship between joint range-of-motion and segmental stability to preserve the intended kinematic sequence of the golf swing. Limitations at the hips, thoracic spine, or ankles commonly force compensatory motion at the lumbar spine or shoulders, increasing injury risk and reducing clubhead speed. Rehabilitation and conditioning should therefore target both **joint-specific mobility** and **intersegmental control**, recognizing that mobility without stability (or vice versa) degrades transfer of angular momentum through the pelvis-thorax-arm kinetic chain.

Mobility protocols must be specific,measurable,and task-oriented. For the lower kinetic chain emphasize hip internal/external rotation and flexion (e.g., **supine hip CARs**, 90/90 rotations), and ankle dorsiflexion (e.g., **weighted ankle dorsiflexion mobilizations**). For the trunk and upper chain prioritize thoracic extension/rotation (e.g., **quadruped thoracic rotations**, dowel-assisted segmental extensions) and scapular upward rotation and posterior tilt (e.g., **banded shoulder dislocations** with controlled thoracic motion). These interventions should include slow, repeated movements through end-range with diaphragmatic breathing to facilitate motor learning and passive tissue adaptation.

Segmental stability training focuses on resistive control of rotation, translation, and anti-extension forces within planes relevant to the swing. Evidence-supported exercises include **Pallof presses** (anti-rotation), **dead-bug progressions** (lumbo-pelvic dissociation), single-leg Romanian deadlifts (frontal/sagittal control), and split-stance cable chops (rotational power with pelvic stability). Load progression should move from isometric holds to slow eccentrics,then to ballistic and golf-specific loaded rotations,emphasizing timed bracing and proximal-to-distal sequencing under perturbation.

Integrating mobility and stability into practice sessions optimizes transfer to on-course performance. Prescribe short mobility primers (5-10 minutes) before range work, followed by targeted stability sets integrated into warm-ups and strength days. Sample weekly dosage for intermediate golfers may include:

- Mobility: 3×/week, 2-3 exercises × 8-12 controlled repetitions.

- Stability: 2-3×/week, 3-4 exercises × 2-4 sets of 6-12 reps (progressing to dynamic/loaded patterns).

- Integration: 1-2 sessions/week of swing-specific resisted rotations (low load → high velocity).

Progressions must be individualized on the basis of objective screening and fatigue management.

objective screening and ongoing monitoring guide intervention efficacy and safe progression. Use simple clinical tests (hip rotation ROM,thoracic rotation AROM,single-leg balance time) alongside performance metrics (clubhead speed variance,ball-flight consistency) and,when available,wearable IMU or 3D motion-capture data to quantify changes in sequencing and segmental contribution. The following concise table offers practical exercise prescriptions for clinic-to-course translation.

| Exercise | Primary Target | Typical Prescription |

|---|---|---|

| Pallof Press | Anti-rotation (core) | 3×8-12s isometric → 3×6-8 dynamic |

| Quadruped T-Spine Rotation | Thoracic mobility | 3×8-10 per side, controlled |

| single-leg RDL | Pelvic/lower-limb stability | 3×6-10 per side, slow eccentrics |

Aerobic and Anaerobic Conditioning Strategies to Enhance On Course Endurance

Golf performance across 18 holes imposes both low‑intensity, long‑duration demands and brief, high‑intensity efforts that rely on distinct metabolic pathways. sustained walking, cognitive load, and repeated rotational efforts primarily tax the oxidative system, while swing‑related peak power, uphill approaches, and short bursts to reach a shot require phosphagen and glycolytic support. An evidence‑informed conditioning strategy therefore addresses both maximal oxygen uptake (VO2max) and short‑duration anaerobic power,recognizing that improved aerobic capacity enhances recovery kinetics between high‑intensity efforts and attenuates fatigue‑related technical decay.

Designing effective sessions follows a periodized, concurrent model that balances volume, intensity, and skill retention. Integrate aerobic base work with targeted anaerobic intervals and on‑course simulations to preserve motor pattern fidelity under fatigue. Representative session types include:

- Steady‑state aerobic: 30-60 min continuous walking or cycling at 60-75% HRmax to build capillary density and recovery capacity.

- Threshold tempo: 20-40 min at lactate threshold to improve sustained pace and fatigue resistance.

- High‑intensity intervals (HIIT): 4-8 × 30-90 sec near maximal efforts with full recovery to enhance VO2max and anaerobic contribution.

- Sprint repeats / power intervals: 6-12 × 10-20 sec maximal sprints with long recoveries to develop phosphagen power relevant to explosive swings.

- On‑course metabolic simulations: combined walking with periodic loaded carries and short sprint efforts to replicate competition demands.

Translating modality to purpose can be simplified in a compact reference. The following table provides actionable dose estimates aligned with targeted adaptations and practical constraints for golfers.

| Modality | Primary System | Typical Dose |

|---|---|---|

| Long walks / steady-state | Aerobic | 3×/wk, 30-60 min |

| Tempo / threshold | Aerobic‑threshold | 1-2×/wk, 20-40 min |

| HIIT (4-8 intervals) | VO2max / glycolytic | 1×/wk, 20-30 min total |

| Sprint / power repeats | Phosphagen | 1×/wk, 6-12 sprints |

Implementation must be individualized by playing level, age, and injury history. Novice and older golfers benefit from a higher proportion of low‑impact aerobic work and gradual introduction of intensity, whereas elite players require precise dosing of HIIT and power work to elicit marginal gains. Objective monitoring-heart rate zones, session RPE, time‑in‑zone, and wearable gait metrics-enables data‑driven adjustments. Importantly,integrate conditioning with technical practice to avoid interference effects: schedule high‑intensity sessions separate from days focused on fine motor skill acquisition or reduce volume on concurrent days.

recovery and progression are essential to consolidate adaptations while minimizing injury risk. Emphasize sleep, nutrition (timed carbohydrate for higher intensity days), and active recovery modalities. A sample microcycle for a moderately trained golfer might include: two aerobic sessions,one HIIT session,one sprint/power day,technical practice on three days,and at least one full rest or active‑recovery day. Key considerations for progression are intensity first, then volume, with frequent reassessments of functional power and endurance metrics to align conditioning with on‑course outcomes.

Nutritional Frameworks to Support Training Adaptation Recovery and Competition Performance

optimizing adaptive responses requires aligning dietary intake with the physiological demands of golf-specific training and competition.Energy availability is the primary driver of anabolic processes, neuromuscular recovery, and immune competence; therefore, caloric intake should be periodized to reflect phases of increased load (strength/power blocks), skill-intensive sessions, and tapering prior to competition. Body-composition targets should be set with functional markers (clubhead speed, repeat power output, mobility) rather than aesthetic norms to preserve neuromuscular capacity while reducing non-functional mass.

Macronutrient prescriptions should be evidence-informed and individualized by body mass, training volume, and session type. General ranges useful for practitioners working with golfers are: carbohydrate 3-7 g·kg−1·day−1 (higher end during heavy on-course practice or double sessions),protein 1.2-2.0 g·kg−1·day−1 with strength emphasis toward 1.6-2.0 g·kg−1·day−1 to support remodeling, and dietary fat providing ~20-35% of energy with emphasis on essential fatty acids.The following quick-reference table offers a concise phase-based template that can be adapted per athlete.

| Phase | Energy focus | Carbs (g·kg−1·day−1) | Protein (g·kg−1·day−1) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Off‑season (build) | Surplus/moderate | 4-6 | 1.6-2.0 |

| Pre‑competition (peak) | Maintenance/periodized | 5-7 | 1.6-1.8 |

| Competition week | Taper & precision | 3-5 (pre-round load ↑) | 1.6-1.8 |

| Post‑round recovery | Replenish & repair | 1.0-1.2 immediately | 0.3-0.4 g·kg−1 within 60-120 min |

Timing and targeted strategies amplify adaptation and on‑course performance. Prioritize a bolus of mixed carbohydrate and high‑quality protein in the early recovery window (example: 30-40 g carbohydrate + 20-40 g protein) to support glycogen resynthesis and muscle protein synthesis. For competition days,implement a pre‑round meal 2-3 hours before teeing off (moderate carbohydrate,low GI for sustained output) and small carbohydrate snacks during play to maintain cognitive function and decision making.Practical meal components include lean proteins, whole grains, fruits, and easily digestible dairy or plant‑based yogurts.

Targeted ergogenic and recovery aids can be integrated where justified by assessment and monitoring. Evidence‑based options and pragmatic considerations include:

- Creatine monohydrate (3-5 g·day−1) for repeat sprint and power preservation during strength phases;

- Omega‑3 fatty acids (food first; supplemental EPA/DHA 1-2 g·day−1 when intake low) to modulate inflammation and support tissue health;

- Caffeine (individualized; ~2-3 mg·kg−1) as an acute cognitive and alertness aid on competition days with tolerance testing in practice;

- Vitamin D and calcium monitoring for bone health, and iron screening for athletes with fatigue or low hemoglobin;

- Hydration strategies using body‑mass changes and electrolyte replacement for rounds >3-4 hours, with small sodium doses in fluids when heavy sweating occurs.

Collectively, these frameworks emphasize monitoring (training load, body composition, subjective recovery, and targeted blood markers) and iterative adjustment to support long‑term adaptation, minimize injury risk, and optimize competition readiness.

Psychological and Psychophysiological Preparation: Mental skills Training and Stress Regulation

Mental skills training for golfers should be conceptualized as a structured, evidence-informed subsystem of physical preparation that targets attentional control, emotion regulation, and decision-making under pressure.Contemporary models emphasize the interplay between cognition and physiology: sustained attentional focus co-varies with autonomic markers (e.g., heart-rate variability), and maladaptive appraisals amplify sympathetic activation and performance decrements. Practitioners should therefore prioritize protocols that simultaneously train cognitive strategies and down-regulate physiological reactivity, using short, repeatable exercises that can be implemented on-course (pre-shot routines, cue-controlled breathing, and stimulus-response rehearsal) to reduce the impact of common cognitive biases such as anchoring and outcome fixation.

Core competencies to be developed within a periodized mental skills curriculum include:

- Attentional control: selective and sustained attention drills, attentional switching, and quiet-eye rehearsal to stabilize perceptual input during the swing.

- Emotional regulation: paced-breathing, progressive muscle relaxation, and reappraisal techniques to modulate arousal and anxiety.

- Imagery and simulation: multisensory rehearsal of course scenarios, pressure shots, and recovery from error to build procedural fluency.

- Self-talk and implementation intentions: scripted cues for shot execution and recovery scripts for error management to mitigate anchoring and perseverative thinking.

- Decision-making under uncertainty: pre-shot routines that enforce facts sampling,risk-reward heuristics,and explicit time limits to reduce cognitive load.

Psychophysiological assessment provides objective indices to tailor interventions and monitor adaptation. Simple, field-friendly metrics (heart-rate variability, respiratory rate, skin conductance) can be triangulated with subjective reports to gauge regulatory capacity and training response. The table below summarizes common metrics and practical applications for golf-specific conditioning:

| Metric | Indicates | Practical Use |

|---|---|---|

| HRV (RMSSD) | Parasympathetic tone / recovery | Baseline monitoring; readiness for high-pressure practice |

| Respiration rate | Arousal level | Paced-breathing biofeedback during pre-shot routine |

| Skin conductance | Sympathetic activation | Stress exposure training; measure of reactivity to simulated pressure |

Integrating psychological and psychophysiological work into an integrative golf-conditioning program requires deliberate sequencing and cross-disciplinary coordination. Early phases emphasize skill acquisition with low stress and high cognitive load separation (skills drilled sequentially), mid-phases apply progressive stressors (time pressure, crowd noise, competitive tasks) combined with physical fatigue inoculation, and late phases simulate tournament conditions to induce ecological validity. Emphasis on recovery modalities (sleep optimization, HRV-informed rest days) ensures that cognitive training does not become an additional stressor but rather a catalyst for adaptation.

Evaluation, ethics, and systems-level alignment are central to sustainable implementation. Assessment frameworks should include objective psychophysiological markers, validated psychological scales, and performance outcomes; interventions must be individualized and delivered in collaboration with sport psychologists and medical professionals when indicated. Programs should reflect broader public-health principles-respect for autonomy, rights-based approaches, and psychosocial safety-ensuring that mental skills work is accessible, non-coercive, and integrated into athlete welfare pathways.Success is best judged by multidimensional criteria: improved task-focused resilience, reduced maladaptive reactivity, consistent execution under pressure, and demonstrable transfer to competitive performance.

Periodized Integrative Programming Aligned with competitive Calendar and Individual Capacity

Long-term planning centers on aligning training epochs with the competition calendar while respecting each athlete’s physiological ceiling and injury history. A macrocycle should translate tournament density into phases that prioritize foundational capacity earlier in the year and progressive specificity as events near. baseline data-comprising three-dimensional kinematic analysis,maximal strength assessments,and aerobic/anaerobic profiles-provides the empirical substrate for individualized progression. Objective baselines enable periodization that is both evidence-based and responsive to the golfer’s unique movement signature.

Within the mesocycle structure, priorities shift predictably from hypertrophy and motor control to power expression and maintenance. Integrative sessions pair biomechanical refinement (e.g., swing sequencing drills, pelvis-trunk dissociation work) with physiological targets (e.g., force-velocity profiling, repeated-sprint endurance). Load progression adheres to classic periodization principles-progressive overload, planned deloads, and taper windows-to optimize adaptation without compromising movement quality.Specificity increases as competition approaches, preserving technical economy under fatigue.

Microcycles operationalize the mesocycle through consistent, replicable templates that include technical, physical, and recovery elements. A sample weekly structure might incorporate:

- Day 1: maximal strength + technical rehearsal

- Day 2: mobility and corrective biomechanics

- Day 3: power and speed-endurance

- Day 4: active recovery + cognitive skills

- Day 5: on-course simulation with pre-shot routine practice

This integrated design enforces transfer between the gym and the course while maintaining planned variability and autoregulatory capacity.

Monitoring is the decision engine: combine laboratory-grade measures (force-plate kinetics, inertial sensor kinematics, ball-flight data) with field-friendly indices (session RPE, heart-rate variability, sleep quality).The table below offers a concise mapping from phase to actionable metrics that inform day-to-day prescription and taper decisions. Use these markers to trigger volume reductions, technique-focused deloads, or intensified recovery strategies.

| Phase | Primary Focus | Representative Metric |

|---|---|---|

| Preparation | Capacity & Movement Quality | 1RM, mobility score |

| Pre-Competition | Power & Specificity | Peak ball speed, force-velocity |

| Competition | Maintenance & recovery | HRV, session RPE |

| Transition | Recalibration & injury Management | Movement screens, pain scales |

Effective implementation requires interdisciplinary communication: strength coaches synchronize periodization with swing coaches, physiotherapists guide load tolerance decisions, and sports psychologists align arousal management with tapering schedules. The plan must be flexible-an evidence-informed framework rather than a rigid script-so that peaking is achieved through iterative adjustments grounded in athlete response. Emphasizing both mechanical efficiency and physiological readiness produces more reliable competitive performance and sustainable athlete development.

Monitoring Assessment and Injury Prevention: Objective Thresholds and Data Driven Interventions

Effective performance surveillance for golf relies on clearly defined, objective thresholds that translate biomechanical signals into actionable risk markers. Establishing baseline norms for each athlete-spinal and hip rotation, trunk lateral flexion symmetry, eccentric hamstring strength and external rotation torque-creates a quantitative foundation for comparison. When values deviate beyond pre-established limits, the data should automatically flag the athlete for targeted evaluation. Thresholds are not static; they must be individualized, sport-specific and adjusted with longitudinal trend analysis rather than single-point measurements.

Below is a concise reference of commonly used objective thresholds and the immediate data-driven response they warrant:

| Metric | Threshold | Recommended action |

|---|---|---|

| Thoracic rotation (°) | < 40° or >10° asymmetry | Mobility + thoracic extension drills |

| Hamstring H:Q ratio | < 0.6 | Eccentric strengthening (Nordic/tempo) |

| Peak rotational velocity (°/s) | < 450°/s vs cohort | Power and rate-specific training |

| Acute:Chronic Load | >1.5 | Reduce volume; modify intensity |

Applied monitoring combines multiple modalities to triangulate risk and performance deficits. Useful tools include:

- Inertial measurement units (IMUs) for swing kinematics and segmental timing;

- Force plates for ground reaction symmetry and weight transfer metrics;

- Isokinetic or hand-held dynamometry for strength and H:Q profiling;

- Validated questionnaires and pain-scales for early symptom capture.

Interventions must be algorithmic and criterion-driven: when a threshold breach is confirmed, implement a staged protocol of corrective mobility, neuromuscular re‑education, load management and progressive return-to-swing testing. Progression decisions should be binary and based on repeatable objective tests (e.g., regain ≥90% strength symmetry, pain-free ROM within normative band, normalized swing kinetics). Integrating coach, therapist and athlete through a shared data dashboard ensures fidelity to the intervention plan and reduces subjective drift.

sustainable injury mitigation hinges on a closed-loop governance model: continuous data collection, automated alerts, clinician-led interpretation and individualized conditioning prescriptions. Risk reduction is achieved by linking measurement to immediate action-not by more data alone. Regular reassessment intervals, documented decision rules and compliance monitoring create the feedback necessary to demonstrate clinical efficacy and justify resource allocation in high-performance golf programs.

Q&A

Below is an academic-style, professional Q&A designed to accompany an article entitled “Integrative Golf Fitness: biomechanics and Conditioning.” The Q&A synthesizes core biomechanical principles, exercise‑physiological considerations, assessment and monitoring strategies, program design, and evidence‑based practical recommendations. Where relevant, the term “integrative” is framed in the broader clinical/health context (i.e., combining complementary disciplines for greater effectiveness) as used in interdisciplinary healthcare programs and authoritative dictionaries [see definitions and program descriptions in refs. 2-3].

Q1. What does “integrative golf fitness” mean in the context of performance enhancement?

A1.integrative golf fitness denotes a structured, interdisciplinary approach that synthesizes biomechanics, exercise physiology, strength and conditioning, motor control, injury prevention, and recovery modalities to optimize swing efficiency, power transfer, endurance, and resilience. The adjective “integrative” reflects the deliberate combination of multiple evidence‑based domains to produce a cohesive training plan (see general definitions of “integrative” and integrative health program frameworks [2-3]).

Q2.What are the principal biomechanical constructs that determine an effective golf swing?

A2. Key constructs include: (1) the kinetic chain and coordinated proximal‑to‑distal sequencing; (2) ground reaction force generation and transfer into the club; (3) dissociation between pelvis and thorax (X‑factor and X‑factor stretch); (4) maintenance of a safe yet mobile spinal posture; (5) appropriate segmental angular velocities and peak rotational velocities; and (6) balanced force production and absorption across single‑leg support phases. These constructs determine the efficiency of energy transfer from the ground to the clubhead.

Q3. How does exercise physiology contribute to golf performance?

A3. Exercise physiology informs training stimulus selection (strength, power, hypertrophy, endurance), metabolic system development, neuromuscular adaptations (rate of force development, intermuscular coordination), and recovery optimization (sleep, nutrition, autonomic balance). Physiological profiling helps quantify an athlete’s capacity to produce the forces and speeds necessary for repeated swings during practice and competition.

Q4.Which muscles and physical capacities are most critical for producing clubhead speed and control?

A4. Critical muscle groups and capacities: (1) lower‑body force production (gluteus maximus, quadriceps, hamstrings) for ground force generation; (2) core stabilizers and rotary musculature (obliques, multifidus, transversus abdominis, erector spinae) for trunk stiffness and dissociation; (3) scapular stabilizers and rotator cuff for arm path and club control; (4) hip internal/external rotators for pelvic rotation; (5) lower limb single‑leg stability and eccentric control for weight transfer; and (6) neuromuscular power and rapid rate of force development (RFD).

Q5. How should mobility and stability be balanced in a golf‑specific program?

A5.Mobility and stability are complementary: joint mobility (thoracic rotation, hip internal/external rotation, ankle dorsiflexion) must be sufficient to allow desired swing kinematics, while local and regional stability (lumbar stabilization, scapular control, single‑leg balance) protects joints and facilitates efficient force transfer. Assessment should identify whether deficits are mobility‑limited or stability‑limited, and interventions should prioritize remediation of the limiting factor before advancing to high‑velocity power work.Q6.What objective assessments are recommended for an integrative golf fitness evaluation?

A6. Recommended assessments:

– Movement screens: functional movement or sport‑specific screens to identify asymmetries.

– Range of motion: thoracic rotation, hip internal/external rotation, ankle dorsiflexion.

– Strength/power testing: countermovement jump (CMJ) for lower‑body power, isometric mid‑thigh pull for maximal force, medicine‑ball rotational throw for rotational power.

– Balance/stability: single‑leg balance or Y‑Balance Test.

– Force/time metrics: force plate analysis (vertical GRF, RFD) if available.

– Swing metrics: clubhead speed,ball speed,launch monitor outputs,and kinematic sequencing (e.g., pelvis vs. thorax angular velocity).

combining physiological and biomechanical measures yields a comprehensive profile for individualized program design.

Q7. Which monitoring metrics best correlate with on‑course improvements?

A7. Metrics with practical translational value: clubhead speed, ball speed, smash factor, carry distance, peak pelvic and thoracic angular velocities, CMJ height/power, medicine‑ball rotational throw distance/velocity, and measures of RFD. Monitoring training load and recovery via session RPE, sleep, and simple wellness questionnaires aids in preventing overtraining and injury.Q8.What types of resistance training modalities best transfer to golf swing performance?

A8. Effective modalities include:

– Maximal and submaximal strength training (compound lifts such as deadlifts, squats, trap‑bar deadlifts) to increase force capacity.

– Rotational and anti‑rotational exercises (cable chops, Pallof press, half‑kneeling chops/lifts) to develop trunk control and transfer.

– Explosive/plyometric training (med‑ball rotational throws, loaded/vehicular hip hinge power exercises) to improve RFD and rotational power.

– Single‑leg strength and trunk‑stability progressions to mirror unilateral weight shift demands.

Q9. How should periodization be applied to a golfer’s conditioning program?

A9. Periodization should be task‑specific and individualized. A typical framework:

– Off‑season (8-12+ weeks): emphasize hypertrophy and maximal strength development.- Pre‑season (6-8 weeks): transition from strength to power via increasing velocity‑specific work and plyometrics.

– In‑season/competitive: maintain strength and power with lower volume, higher intensity/quality sessions and prioritize recovery and on‑course practice.

Microcycles should alternate loading and recovery days, with frequent reassessment every 4-8 weeks.

Q10. What are safe progressions for power development in golfers?

A10. Progressions: (1) establish baseline mobility and strength; (2) introduce medicine‑ball rotational throws (from bilateral to unilateral, seated to standing to step‑through), emphasizing technique; (3) incorporate loaded ballistic lifts (kettlebell swings, trap‑bar jump variations) and short‑distance plyometrics; (4) progress to high‑speed, golf‑specific implements (weighted club swings, speed sticks) while monitoring swing mechanics. Ensure adequate eccentric control capacity before high‑velocity rotational work.

Q11. How does the kinetic chain concept shape exercise selection and coaching cues?

A11. Exercises should promote sequential proximal‑to‑distal energy transfer: generate ground force (lower body), transfer through a stable yet rotationally dissociable trunk, and translate into high angular velocity at the club.Coaching cues should emphasize stable base, initiating force from the ground and hips, maintaining appropriate spinal posture, and timing the pelvis‑thorax separation to maximize stretch‑shortening benefits.

Q12. What injury mechanisms are common in golfers, and how does an integrative program mitigate risk?

A12. Common injuries: low back pain (often related to high shear and compression during rotation), wrist/forearm overload, shoulder impingement/rotator cuff strains, and knee/hip overuse. Mitigation strategies: restore thoracic mobility, improve eccentric control of the trunk and hips, correct swing technical faults that increase joint stress, implement progressive loading for connective tissue adaptation, and incorporate prehabilitation exercises for rotator cuff and scapular stabilizers. Periodic biomechanical analysis to detect deleterious movement patterns is also recommended.

Q13. How do you integrate technology (motion capture, force plates, launch monitors) into practice without overreliance?

A13. Use technology to quantify benchmarks, validate training effects, and detect meaningful changes. Prioritize tools that directly inform the coaching or conditioning decision (e.g., launch monitor for clubhead/ball speed, force plates for RFD). Interpret data in the context of clinical and performance observations; do not substitute objective measures for sound clinical reasoning. Technology should augment, not replace, expert assessment.

Q14. What evidence supports transfer from gym‑based gains to on‑course improvements?

A14. The literature generally supports that increases in lower‑body strength, rotational power, and neuromuscular RFD can translate to improved clubhead and ball speed when training includes sport‑specific velocity and movement patterns.Transfer is optimized when strength gains are coupled with high‑velocity, golf‑specific movement training (i.e., velocity‑specific adaptation). Quality randomized controlled trials in elite populations remain limited; therefore, individualized testing and pragmatic field measures are essential.Q15. How should return‑to‑play or rehabilitation programs be structured after injury?

A15. Use a staged, criterion‑based progression:

– Phase 1: pain control, restore pain‑free mobility and basic motor control.

– Phase 2: progressive loading to restore strength,endurance,and eccentric tolerance of relevant tissues.- Phase 3: reintroduce rotational control and golf‑specific mechanics at low velocity (dry swings).

– Phase 4: graded return to full‑speed swings and on‑course practice, monitored by objective metrics (clubhead speed, pain scores, movement quality).

Clear stop/go criteria and interprofessional communication (physician, physiotherapist, coach) are essential.

Q16.What are practical sample exercises for key deficits?

A16. Examples:

– Thoracic mobility: thoracic rotation on foam roller or quadruped T‑spine wind‑ups.

– Hip mobility: 90/90 switch, hip CARs (controlled articular rotations).

– Anti‑rotation/core: Pallof press, half‑knee anti‑rotation holds.

– Rotational power: seated/standing med‑ball rotational throws, step‑through rotational throws.

– Lower‑body force/power: trap‑bar deadlift (strength),broad jumps or loaded CMJ (power).- Single‑leg strength: Bulgarian split squat, single‑leg Romanian deadlift.

Progressions should be based on validated competency criteria before increasing speed or load.

Q17. How should coaches quantify meaningful change in performance metrics?

A17. Use both absolute and relative change thresholds derived from test reliability: for example, CMJ increases that exceed the minimal detectable change (MDC) indicate real advancement; similarly, increases in clubhead speed of ~1-2 mph are often meaningful in recreational golfers but context dependent. Combine objective metrics with on‑course performance (score,strokes gained) for holistic evaluation.

Q18. What role do non‑physical factors (nutrition, sleep, psychological skills) play in integrative golf fitness?

A18. Non‑physical factors are integral. Adequate energy availability and protein support tissue adaptation; hydration and micronutrient status affect neuromuscular function; sleep is critical for recovery and consolidation of motor learning; psychological skills (focus, arousal regulation, pre‑shot routine) interact with physical readiness to determine competition outcomes. An integrative program coordinates these domains with training prescription.

Q19. What are current research gaps and opportunities for investigators?

A19. Gaps include: high‑quality randomized trials comparing integrated strength/aerobic/skill interventions to skills‑only programs in diverse populations; mechanistic studies linking specific physiological adaptations (e.g., RFD, eccentric capacity) to swing kinematics; longitudinal work on injury prevention efficacy of specific prehabilitation protocols; and development of sport‑specific normative data for strength, power, and mobility metrics in elite and sub‑elite golfers.

Q20.What are succinct practical recommendations for coaches and clinicians implementing an integrative program?

A20. Practical takeaway:

– Begin with comprehensive biomechanical and physiological assessment.

– Correct limiting mobility/stability issues before rapid power progression.

– Build a base of strength, then transition to power and velocity‑specific training.

– Incorporate sport‑specific drills (med‑ball throws,weighted club swings) for transfer.

– Monitor objective metrics and athlete wellness; individualize periodization.

– Use interdisciplinary collaboration (coach, S&C, physiotherapist, medical) to align technical, physical, and health goals-consistent with integrative program principles in healthcare [2-3].

References and resources

– For definitions and the integrative framework, see Cambridge dictionary’s definition of “integrative” [2], and institutional integrative health program descriptions (e.g., Weill Cornell/newyork‑Presbyterian) as exemplars of evidence‑based, individualized interdisciplinary approaches [3]. For clinical integrative medicine perspectives, see resources such as Johns Hopkins Integrative Medicine [1].

– Practical assessment and training modalities referenced above are informed by contemporary strength & conditioning and sports biomechanics texts and peer‑reviewed literature; practitioners should consult primary literature for population‑specific protocols and measurement reliability values.

Provided links (for context on “integrative” and integrative health program frameworks):

– https://dictionary.cambridge.org/us/dictionary/english/integrative [2]

– https://weillcornell.org/integrative-health-program [3]

– https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/health/wellness-and-prevention/integrative-medicine [1]

If you would like,I can:

– Convert this Q&A into a formatted FAQ for publication;

– Add citations to specific biomechanics and S&C research papers;

– Produce a sample 8‑ to 12‑week periodized program with progressions and weekly templates.

Final Thoughts

an integrative approach to golf fitness-one that synthesizes biomechanical analysis, sport-specific conditioning, and complementary domains of physical and psychological health-offers a coherent framework for enhancing performance and reducing injury risk. The term “integrative” conveys the deliberate combination of multiple elements to produce more effective outcomes; applied to golf, this means aligning movement science, strength and conditioning principles, motor control training, and recovery strategies into individualized programs that respect the athlete’s functional capacities and competitive demands.

For practitioners,the implications are practical and immediate. Routine implementation of objective biomechanical assessment (e.g.,kinematic and kinetic profiling),periodized conditioning plans tailored to swing demands,and ongoing monitoring of movement quality and training load will enable evidence-informed decision making. Moreover, incorporating broader integrative elements-such as psychological skills training, nutritional support, and rehabilitative modalities-can optimize adaptability and resilience, consistent with holistic models of care used in integrative therapy and medicine.

future work should prioritize high-quality translational research to define best practices: longitudinal and randomized trials that test multimodal interventions, mechanistic studies linking specific conditioning adaptations to swing biomechanics, and development of standardized outcome measures relevant to on-course performance and injury incidence. By fostering interdisciplinary collaboration across biomechanics, strength and conditioning, sports medicine, and sport psychology, the integrative paradigm can evolve from conceptual promise to demonstrable impact-advancing both the science and practice of golf fitness.

Integrative Golf Fitness: Biomechanics and Conditioning

Why an Integrative Approach Improves Golf Performance

An integrative golf fitness strategy blends biomechanics,physiological profiling,targeted strength,mobility,and conditioning to enhance swing mechanics,increase clubhead speed,and reduce injury risk. This approach treats the golfer as a whole system: improving movement quality, power generation, and energy system capacity so technique improvements transfer to the course.

Core Biomechanical Principles of the Golf Swing

Kinetic chain and sequencing

Efficient golf swings distribute force from the ground up through the legs, hips, torso, shoulders, arms, and finally the club.proper sequencing (legs → hips → torso → shoulders → arms → club) maximizes clubhead speed and consistency.

Separation and rotational power

Pelvis-shoulder separation (X-factor) creates elastic energy for faster rotation. Improving thoracic mobility, hip rotation, and eccentric control allows safe increases in rotational velocity and ball speed.

Ground reaction forces (GRF)

Generating and transferring GRF through the lead leg during the downswing is a major source of power.Strength and stability in the lower body enhance the ability to push into the ground and convert force to clubhead speed.

Assessment & Physiological profiling (What to Test)

Before designing programs, run a concise golf-specific assessment to identify limiting factors:

- Movement screening: single-leg squat, overhead squat, T-spine rotation

- Range-of-motion (ROM): thoracic rotation, hip IR/ER, ankle dorsiflexion

- Strength tests: single-leg RDL, loaded carry, squat or vertical push

- Power tests: medicine-ball rotational throw, countermovement jump, clubhead speed with launch monitor

- Balance and stability: single-leg balance and dynamic reach

- Cardio baseline: 20-30 minute walk/run or GPS for round recovery data

Tip: Use a launch monitor (or radar app) plus simple strength/power tests to track changes in ball speed and rotational power over time.

Program Components - Strength, mobility & Conditioning

Strength & Power (Priority for Clubhead Speed)

Goal: Build a resilient base and increase rotational and vertical power while protecting the spine.

- Hip-focused lifts: Romanian deadlifts, trap-bar deadlifts, split squats

- Rotational power: medicine-ball rotational throws, side throws, and slams

- Anti-rotation & core: Pallof press, cable anti-rotation holds, farmer carries

- Explosive lifts: loaded jump squats, kettlebell swings (light to moderate load)

Mobility & Joint Integrity

A mobile thoracic spine, hips, and ankles enable appropriate swing mechanics without compensations that lead to injury.

- Thoracic rotation drills (open-book, 90/90, band-assisted rotations)

- Hip mobility (90/90 transitions, lunge with rotation, hip CARs)

- Ankle mobility (dorsiflexion wall drills, controlled tibial progression)

- Shoulder care (scapular stability, rotator cuff work, thoracic extension)

Conditioning & Energy System Development

Golf requires a steady aerobic base for walking the course plus repeated short bursts of high neuromuscular demand (swinging, walking uphill, shots from rough). conditioning should be golf-specific and time-efficient.

- Aerobic baseline: brisk walking, cycling, or elliptical 2-3x/week (20-45 minutes)

- High-intensity interval training (HIIT): short sprints, hill repeats, or circuit-style work for recovery between high-effort swings

- Golf-specific metabolic conditioning: circuits combining movement, medicine-ball throws, and short loaded carries to mimic round demands

Injury Prevention & Common Problem Areas

Targeted prehab reduces incidence of low back pain, shoulder issues, and wrist/elbow strains.

- Low back: emphasize core stability, hip hinge mechanics, and thoracic mobility to avoid hyperextension and shear

- Shoulder: balance rotator cuff strengthening with scapular stabilizers and thoracic extension

- Elbow/wrist: manage load with forearm eccentric work and proper grip technique

Warm-up and On-Course Preparation

A dynamic warm-up primes the nervous system and improves immediate swing quality. Keep pre-round and pre-shot routines simple and repeatable.

- 5-8 minute dynamic warm-up: glute bridges, lateral lunges, thoracic rotations, band pull-aparts

- Progressive swing prep: half swings → three-quarter swings → full swings with mid-iron → driver

- Pre-shot routine: breathing, visualization, and a consistent setup to limit stress and speed variability

monitoring Progress: Metrics That Matter

Track improvements using objective and subjective measures:

- Clubhead speed and ball speed (launch monitor data)

- Distance gains (carry and total) and dispersion (accuracy)

- Strength/power metrics (jump height, medicine-ball throw distance, bar speed)

- Mobility ROM and pain-free range during swing

- Perceived recovery and fatigue (session RPE, sleep, soreness)

Sample 8-Week Integrative Golf Fitness Plan (Overview)

Below is a simple, creative weekly template. Adjust loads, volumes and rest to individual needs. Two strength sessions + 2 conditioning sessions + daily mobility is an effective structure.

| Week | Strength Focus | Power/Conditioning |

|---|---|---|

| 1-2 | Foundations: hinge, squat, carry (3x/week light) | Med ball throws, brisk walks (2x/week) |

| 3-4 | Build strength: deadlift, split squats, Pallof press | Short HIIT + rotational med ball work |

| 5-6 | Power emphasis: jump squats, plyo push-ups, heavy carries | Mixed circuits + on-course practice sim |

| 7-8 | Peak & maintenance: moderate loads, speed-focused lifts | Golf-specific interval circuits, mobility maintenance |

Practical Tips for Faster gains on the Course

- Prioritize movement quality over heavy loads – a clean hinge and hip rotation are worth more than raw weight lifted.

- Consistency matters: 2-3 guided sessions weekly for 8-12 weeks yields measurable clubhead speed and accuracy gains.

- Match training to the season: focus on hypertrophy and strength in the off-season; power and on-course transfer close to and during season.

- Use short velocity-based or power sessions to maintain speed without accumulating fatigue.

- Get swing feedback (coach or launch monitor) to ensure physical gains translate into better ball flight and dispersion.

Case Study - Translating Strength Gains to Clubhead Speed (Hypothetical)

Player: 45-year-old amateur with 85 mph driver speed, mild low-back discomfort, limited thoracic rotation.

Intervention over 12 weeks:

- Assessment → corrective mobility (thoracic rotations, hip mobility)

- Strength: twice weekly strength training focusing on hip hinge, single-leg stability, loaded carries

- Power: medicine-ball rotational throws and short explosive lower-body work

- Conditioning: moderate aerobic base + 1 HIIT session/week

Outcome: +4-6 mph driver speed (objective launch monitor), reduced low-back soreness, improved ball dispersion and recovery between holes. Exmaple shows how integrated biomechanics and conditioning change both health and performance.

when to Seek Professional Help

Work with PGA coaches, physical therapists, or certified strength and conditioning specialists when:

- you have persistent pain during or after the swing

- you need a tailored rehab or return-to-play program

- you wont detailed biomechanical analysis (3D motion, force plates, launch monitor data)

Quick Reference – Key Exercises for Golfers

- Pallof Press – anti-rotation core control

- Med ball Rotational Throw - rotational power

- Single-leg Romanian Deadlift – hip posterior chain and balance

- Split Squat or Bulgarian Split Squat – unilateral leg strength

- Thoracic Spine Windmills and Open-Book – T-spine mobility

- Kettlebell Swing – hip hinge power and stamina

Note: Always progress gradually and prioritize movement quality and pain-free range. Integrative golf fitness optimizes the body so the swing has a stronger and safer foundation.

Further Steps & Resources

To build an individualized program, combine the assessment data above with the player’s goals (distance vs. accuracy), available time, and current health. Consider periodic re-assessments every 6-12 weeks to guide progression and ensure on-course carryover.

For more advanced biomechanical feedback, look for specialists offering launch monitor sessions, 3D motion capture, or force-plate analysis – these tools can pinpoint where physical improvements produce the biggest swing gains.