The follow-through phase of the golf swing is an essential, yet comparatively neglected, element of high-level performance. Beyond finishing posture, the follow-through captures the final coordination of body segments, the redistribution and absorption of angular and linear momentum generated during the downswing, and the neuromuscular strategies that stabilize the torso and upper limbs to manage shot dispersion. Accurate intersegmental timing in this interval contributes to direction control and club-face management; conversely, inappropriate mechanics or inadequate active deceleration can increase loading on the lumbar spine, shoulder girdle, and elbow and raise injury likelihood.Thus, a comprehensive biomechanical profile of the follow-through is crucial for refining performance and designing focused injury-mitigation programs.

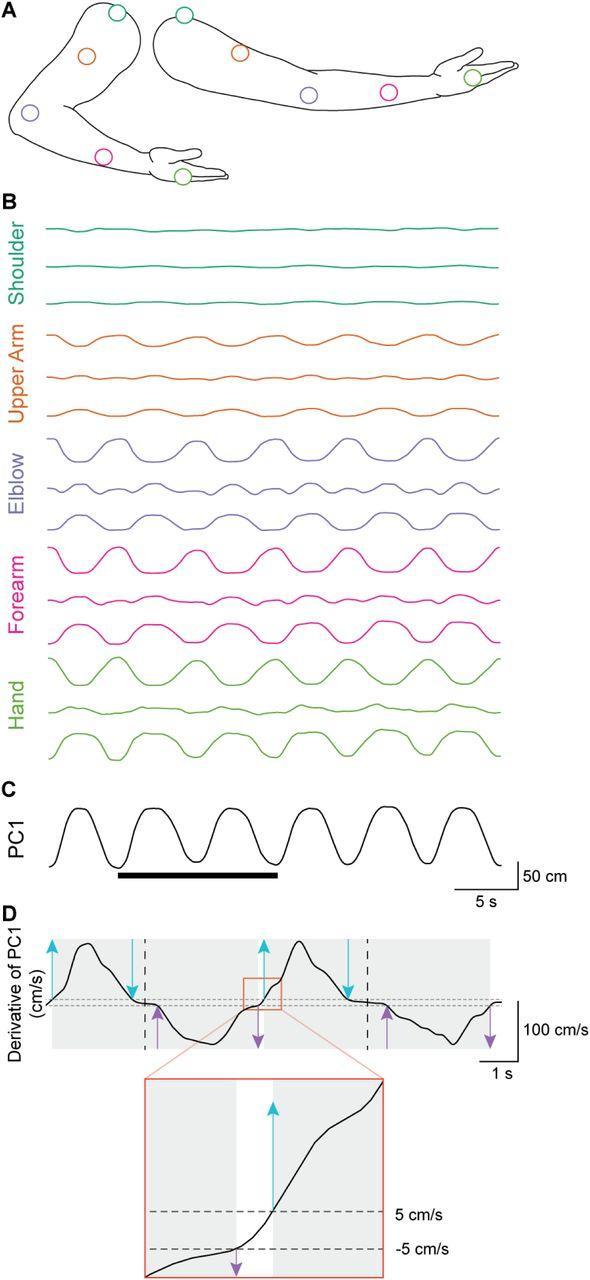

Kinematic description – measuring spatial-temporal relationships, segment speeds, and joint configurations – supplies an essential map of follow-through motion. It is indeed critically important to separate these kinematic observations (movement without forces) from kinetic or dynamic analyses that include forces and moments; both are needed for a full mechanistic account. At the same time, neuromuscular investigation – typically using surface electromyography (EMG) combined with muscle-tendon models – uncovers the timing, intensity, and coordination of muscular activity that generate, shape, and brake segment motion during the follow-through. Bringing kinematic and neuromuscular perspectives together enables evaluation of how muscle recruitment patterns govern joint sequencing and momentum transmission, and how active braking strategies reduce injurious loads.

This manuscript presents an integrated kinematic-neuromuscular examination of the golf follow-through with three aims: (1) describe common joint-sequencing templates and intersegmental momentum pathways in skilled golfers; (2) identify muscular activation signatures that enable active deceleration and consistent ball flight; and (3) link biomechanical patterns to indicators of musculoskeletal loading that may elevate injury risk. Using high-resolution motion capture synchronized with EMG and inverse-dynamics modeling, the work connects descriptive motion patterns with force-based explanations to inform practical coaching cues and rehabilitation methods that enhance shot consistency while lowering injury exposure.

Clarifying how the kinematic chain and neuromuscular control interact during the follow-through advances theoretical models of high-speed ballistic actions and yields applied guidance for improving performance and musculoskeletal resilience in golfers.

Kinematic Cascade in the Follow-Through: How Segments Share Momentum from Pelvis to Hand

the follow-through commonly unfolds as a proximal-to-distal cascade: the pelvis carries forward rotation immediately after ball exit and hands off angular momentum to the trunk, shoulder complex, arms and finally the wrists and hands.This ordered progression stabilizes the clubhead path while enabling distal segments to reach high angular velocities with relatively modest local effort at the wrist. Kinematic investigations consistently show tight temporal coupling across these links: peak angular speeds migrate from proximal to distal segments, and coordination is achieved by tuning rotational amplitude and the timing of deceleration.

Principal joint roles can be summarized as:

- Pelvis: continued internal rotation and controlled posterior tilt set the baseline momentum and begin energy transmission through the chain.

- Trunk/Thorax: sustains rotation and functions as a temporal buffer, absorbing remnant energy and helping determine club-face orientation through thoracic rotation and controlled extension.

- Shoulder/Scapula: convey rotational power to the upper limb while scapular stability limits unwanted humeral translation.

- Elbow/Forearm: manage extension and pronation timing, which are key for path control and face angle at release.

- Wrist/Hand: perform precise deceleration, attenuating late energy and guiding club-face closure to protect accuracy and distal tissues.

Typical timing and magnitude (for comparative reference):

| Joint | Peak Angular Velocity (deg·s⁻¹) | Relative timing (ms,0 = impact) |

|---|---|---|

| Pelvis | 700-950 | 0-20 |

| Trunk | 850-1,100 | 20-40 |

| Shoulder | 1,000-1,300 | 30-60 |

| Wrist/Hand | 1,200-1,800 | 50-100 |

These ranges are presented for comparative insight rather than diagnostic use; individual anatomy,swing intent and club selection will modify absolute magnitudes and timing.

Neuromuscular coordination during the follow-through emphasizes controlled eccentric actions that slow distal segments while preserving coordinated momentum flow. Typical EMG patterns reveal early activation of hip extensors and trunk rotators to maintain pelvis and thorax rotation,followed by time-locked eccentric bursts in rotator cuff and wrist extensor muscles that dissipate residual angular energy. Robust scapular control and appropriate co-contraction of shoulder stabilizers limit translational loading and reduce the incidence of impingement or overuse symptoms in the lead shoulder. From a motor-control standpoint, the nervous system regulates phase-specific stiffness – lower stiffness in distal links during acceleration and higher stiffness during deceleration – supporting both effective power transfer and precise club-face regulation.

Coaching and training implications are straightforward: prioritize exercises and drills that reinforce proximal initiation and intentional distal braking, and apply objective feedback to promote reproducibility. Practical recommendations include:

- Sequencing drills: reinforce pelvis-first rotation while constraining excessive wrist motion to ingrain proximal driving forces.

- Eccentric control work: slow-lengthening shoulder and wrist routines to bolster deceleration capability.

- Biofeedback approaches: use wearable inertial sensors or high-speed video to display timing relationships and order of peak velocities.

Progress can be tracked with measurable targets such as pelvis-to-thorax separation (degrees), intersegmental peak-shift (ms), and relative wrist angular velocity – metrics that relate closely to accuracy, repeatability and injury risk reduction.

Momentum Flow and Energy Dissipation During the Follow-Through: Effects on Ball Flight and Club Deceleration

The follow-through is the concluding expression of energy that began in the lower limbs and crossed the trunk into the club. Efficient production follows a proximal-to-distal release pattern in which rotational inertia accumulates in pelvis and torso and is successively transmitted through the shoulders, forearm pronation, and wrist unhinging. Biomechanically, the conservation and redirection of angular momentum across segment interfaces – frequently enough termed segmental coupling – determine how much kinetic energy reaches the clubhead at and after contact. Interruptions to this chain (mistimed rotation, premature braking, or segmental dissociation) reduce transfer efficiency and leave more residual energy to be absorbed later in the follow-through.

At ball impact the system transitions from energy generation to impulse transfer and regulated dissipation. The split between linear and angular momentum imparted to the ball depends on dynamic loft, effective angle of attack and the contact patch; thus, small clubface or impact-location deviations produce detectable changes in launch angle, spin and carry distance. after contact the club still contains translational and rotational energy that must be shed without jeopardizing joint integrity – a role where neuromuscular control is central. The interaction of impulse-momentum relationships and elastic recoil in musculoskeletal tissues shapes both ball outcomes and the club’s deceleration profile.

Deceleration is an active, centrally controlled process that balances performance objectives and tissue protection. Common biomechanical strategies include:

- Eccentric braking of lead-side musculature (rotator cuff, scapular stabilizers, biceps) to absorb rotational loads.

- Lower-limb force modulation – gradual reduction of ground-reaction impulses via contralateral limb loading and hip stabilization.

- Plane-specific compliance in sagittal and transverse axes through controlled knee and spinal flexion to blunt shock transmission.

Modeling and measurement work isolates several determinants that routinely link follow-through mechanics with ball flight and club deceleration. Representative relationships include:

| Determinant | Typical Effect |

|---|---|

| late proximal rotation | Higher clubhead speed and reduced spin variability |

| High off-center impact | Shifted launch axis and elevated deceleration torque |

| Insufficient eccentric control | Rapid post-impact slowdown and increased injury risk |

In applied settings, coaches and clinicians should measure both how effectively energy moves forward and how well residual momentum is dissipated. Useful metrics include segmental angular velocities, post-impact deceleration of the club (e.g., change in g over time), ground-reaction force impulse profiles, and EMG timing of braking muscles. Training plans that blend proximal power development (plyometrics, rotational medicine-ball throws) with eccentric-strengthening and neuromuscular-control drills generally optimize the trade-off between ball performance and safe deceleration. Prioritizing consistent sequencing, reliable impact mechanics, and graduated deceleration practice links maximal performance with reduced injury exposure.

Neuromuscular Timing: EMG Patterns from Late Downswing through Follow-through

Activation patterns in the late downswing and follow-through typically follow a proximal-to-distal gradient: trunk stabilizers and hip extensors produce large preparatory bursts that are then followed by sequential activation in the pelvis, thigh and distal upper-limb muscles. EMG envelopes often rise rapidly during the final 120-40 ms before impact, with many muscles reaching peak activity within the first 100 ms after contact. Simultaneous short-latency co-contraction in shoulder and trunk musculature suggests an anticipatory stabilization strategy that prepares the kinetic chain for momentum transfer and braking demands.

Temporal metrics from averaged EMG traces quantify relative contributions. Representative onset-to-peak latencies (ms relative to ball contact) for a typical experienced player are shown below:

| Muscle | Onset (ms pre‑impact) | Peak (ms post‑impact) |

|---|---|---|

| Erector spinae | -120 | +40 |

| Gluteus maximus | -90 | +30 |

| External oblique | -60 | +80 |

| Rectus femoris | -40 | +20 |

| Biceps brachii | -20 | +100 |

Distinct EMG fingerprints separate skilled from novice performers: experienced golfers tend to show earlier preparatory activation, sharper peaks with briefer bursts, and lower trial-to-trial variability. Electrophysiological markers used to quantify these differences include RMS amplitude, shifts in mean/median frequency (reflecting motor-unit recruitment and firing-rate dynamics), and intermuscular coherence in alpha-beta bands – an index of effective phase coupling across segments. From these markers the practical takeaways are:

- Training focus: cultivate anticipatory core and hip activation to improve energy transfer efficiency.

- Drill design: include resisted rotations and eccentric shoulder work to enhance braking capability.

- Assessment: use within-athlete EMG baselines and MVC normalization to detect true adaptations.

viewed as a control task, the follow-through is primarily an active deceleration challenge rather than a passive aftermath of impact. Eccentric posterior-chain activity and coordinated antagonist bursts around the shoulder constrain peak joint loads and guide club-face behavior. Fine-tuning the timing – not only the magnitude – of these bursts reduces angular variability at the wrist and clubhead at impact, thereby improving accuracy and lowering repetitive-load injury potential. Interventions that target timed eccentric strength, proprioceptive feedback, and intersegmental timing are therefore likely to produce both performance and health benefits.

Methodological rigor is essential when interpreting EMG data. To improve reproducibility, studies should report electrode positions according to SENIAM/ISB guidance, apply band-pass filtering (e.g., 20-450 Hz), normalize to task-specific MVCs, and use time-warping or event-aligned ensemble averages to line up late downswing events. Analytical tools such as cross-correlation, time-frequency decomposition (wavelet or STFT), and coherence analyses add complementary insight into coupling and recruitment patterns. Future research would benefit from longitudinal interventions, expanded sampling of proximal trunk musculature, and tighter synchronization of EMG with inertial/optical kinematics under ecologically valid swing conditions to translate lab findings into coaching practice.

Active Braking and Eccentric Muscle Roles: Consequences for Joint Loading and Tissue Stress

Eccentric contractions during the concluding phase of the swing are the main neuromuscular mechanism that dissipates the high rotational and translational energies produced earlier. These controlled lengthening actions are coordinated with joint motion to decelerate distal links while preserving global posture. EMG evidence commonly shows increased eccentric activation of the posterior shoulder complex, hip extensors and trunk rotators immediately following contact, with peak activity aligned to moments of rapid angular slowdown at wrist and elbow. Effective eccentric control yields a graded reduction in joint angular velocities, reducing instantaneous peak loads on passive structures and spreading stress across multiple muscle-tendon units.

- Shoulder (rotator cuff, posterior deltoid): resist internal-rotation and abduction moments.

- Elbow (brachioradialis, triceps): absorb valgus and extension torques.

- Trunk (obliques, erector spinae): manage axial deceleration and dissipate transverse-plane energy.

- Hips (gluteus maximus, hamstrings): stabilize the pelvis and moderate ground-reaction transfer.

From a joint-loading perspective, well-timed eccentric braking shifts peak stress away from passive tissues (cartilage, ligaments) and toward contractile elements.When eccentric capacity or timing is compromised, models and measurements reveal higher joint reaction forces and focal tissue strain – commonly at the lateral elbow and posterior shoulder. Biomechanical simulations indicate that modest delays (e.g., 10-20%) in peak eccentric activation can raise instantaneous joint loads by a similar proportion, increasing microtrauma accumulation across repeated swings. Thus,both the magnitude and timing of eccentric torque production are critical drivers of cumulative tissue stress in high-volume practice.

| Region | Primary Eccentric Role | Representative Peak (%MVC) |

|---|---|---|

| Shoulder | Decelerate internal rotation | 60-85% |

| Elbow | Absorb extension/valgus torques | 45-70% |

| Trunk | Control axial/transverse decel | 50-80% |

Interventions should therefore emphasize eccentric strength, coordinated intermuscular timing and proprioceptive control to improve deceleration mechanics. Effective strategies include progressive eccentric overload, drills that transition from plyometric to controlled-eccentric demands, and neuromuscular re-education that targets pre-activation and phase-specific co-contraction. Wearable IMUs and EMG systems can detect temporal offsets and flag athletes with suboptimal braking patterns. Coaches and clinicians should also implement load-management practices that balance intense training with appropriate recovery to limit cumulative tissue damage.

In applied terms the prescription follows a three-step flow: assess eccentric capacity and timing, train sport-specific eccentric resilience, and monitor for increases in joint reaction or pain reports. Relevant drills include resisted follow-through decelerations, slow-eccentric rotational lifts and single-leg eccentric loading to strengthen pelvic and lower-limb control. Emphasizing proximal stability to support distal regulation – together with periodic technique cues to avoid late-phase velocity spikes – helps reduce abnormal tissue loads and preserves long-term shoulder, elbow and lumbar health in players who log high repetitions.

Follow-Through Mechanics and Shot Outcomes: Kinematic Links to Accuracy and Performance

Distal-segment behavior in the post-impact interval measurably affects final ball characteristics. High-resolution kinematics demonstrate that peak trunk rotational speed and maintained arm extension through the follow-through correlate positively with clubhead speed at impact and with narrower lateral dispersion. In contrast, excessive late wrist flexion or uncontrolled ulnar deviation is associated with increased spin-axis variability. These findings underscore that the follow-through continues to encode important information about magnitude and direction of clubhead motion, not merely aesthetics.

Neuromuscular sequencing data reinforce a proximal-to-distal activation pattern: peak discharge in lumbar and thoracic paraspinals typically precedes deltoid and forearm bursts by several tens of milliseconds. EMG-derived metrics – onset latency, integrated amplitude, and co-contraction indices – align with reductions in within-subject shot dispersion when athletes maintain consistent timing windows. Ground-reaction force traces during late support phases show that dependable deceleration through the lead leg supports repeatable segmental separation and lower kinematic variability.

Selected empirically derived relationships (typical effect sizes from controlled biomechanical studies):

| Metric | Kinematic Correlate | Typical Relationship |

|---|---|---|

| Clubhead speed | Peak trunk rotation rate | positive association (r ≈ 0.60-0.80) |

| Shot dispersion | Timing variance of wrist pronation | Positive relationship (greater variance → more dispersion) |

| Spin-axis consistency | Arm extension at follow-through | Negative association with side-spin variability |

To convert kinematic insight into coaching targets, adopt clear, measurable KPIs such as:

- Peak trunk rotation velocity – maintain a reproducible peak within the player’s safe range.

- End-range arm extension – achieve consistent extension to limit clubface rotation variability.

- Wrist pronation timing – align pronation onset in a narrow post-impact window.

- Timing variability – reduce standard deviation of intersegmental onset times across trials.

- Lead-leg support impulse – ensure stable deceleration to build a repeatable kinetic base.

for field use, combine wearable IMUs for rotational kinematics, force plates for support-phase kinetics, and surface EMG for sequencing; then layer targeted drills that emphasize tempo and proximal stability. Real-time auditory or haptic feedback that reduces timing variability frequently enough shortens the learning curve more than verbal cues alone. Ultimately, aligning kinematic thresholds with neuromuscular timing goals yields the moast reliable accuracy gains while respecting athlete-specific constraints.

Injury Risk Profiles from Follow-Through Demands: Vulnerabilities and What Can Be Changed

The follow-through concentrates considerable eccentric loading through the posterior chain and the upper-extremity kinetic chain, creating predictable areas of vulnerability. The lumbar spine is subject to combined rotation and extension moments during deceleration, increasing facet shear and annular loading – especially in players with pre-existing degenerative changes. The glenohumeral joint endures rapid deceleration demands on the rotator cuff and posterior capsule, raising the risk of tendinopathy and microinstability when eccentric capacity is inadequate. Distal joints (elbow and wrist) commonly show overload syndromes from abrupt torsional forces and hurried release patterns; medial elbow and radial wrist tissues are often implicated in late-release mechanics.

Neuromuscular variables influence these structural risks by shifting the timing and magnitude of force distribution. Delayed or muted eccentric activation of serratus anterior, posterior rotator cuff and scapular stabilizers transfers load to passive capsulo-ligamentous tissues; likewise, asynchronous sequencing between pelvic rotation and thoracic counter-rotation increases lumbosacral shear. Fatigue-induced alterations in motor-unit recruitment reduce braking efficiency, and inter-limb asymmetries – measurable via EMG or kinematic indices – have been associated with higher rates of overuse injury. Neuromuscular profiling thus helps separate intrinsic capacity deficits from purely technical faults.

Technique-focused adjustments can meaningfully lower injury risk by redistributing forces and improving deceleration control. Practical coachable aims include:

- Smoother deceleration curve: encourage progressive release rather than abrupt stopping to reduce peak eccentric loads.

- Optimized weight transfer: maintain center-of-mass progression to avoid compensatory trunk shear.

- Controlled thoracic rotation: limit excessive extension-rotation coupling at ball exit to protect lumbar facets.

- scapulothoracic stabilization cues: strengthen proximal control to offload rotator-cuff tendons.

All of these targets can be trained through drills, video feedback and cueing that integrate biomechanical intention with neuromuscular retraining.

| Injury | Primary Mechanism | Modifiable Target |

|---|---|---|

| Low back pain | Rotation-extension shear during deceleration | Trunk sequencing; pelvic control |

| Rotator cuff tendinopathy | Eccentric overload; scapular dyskinesis | Scapular stability; eccentric strength |

| Medial elbow pain | Sudden valgus/varus torques at release | Release timing; forearm deceleration |

Prevention and rehab should marry progressive neuromuscular conditioning to monitored technical revisions. Eccentric strengthening of the posterior chain and rotator cuff, plyometric-to-control progressions for deceleration, and symmetry-focused motor-control drills all reduce tissue-strain vulnerability. Objective monitoring – using kinematic thresholds, session load metrics and periodic EMG or strength testing – supports graduated return-to-play decisions and quantifies residual risk. Tailoring programs to individual age, injury history, adaptability and neuromuscular capacity produces the most reliable outcomes for minimizing follow-through-related injuries while maintaining reproducible performance.

Measurement Protocols: best Practices for Motion Capture, Force Plates and EMG in Follow-Through Analysis

| System | Typical Sampling | Recommended Filter |

|---|---|---|

| Motion capture | 200-500 Hz | Low-pass 6-15 Hz |

| Force plate | 1000-2000 Hz | Low-pass 20-50 Hz |

| Surface EMG | 1000-4000 Hz | band-pass 20-450 Hz |

- Rotator cuff complex (supraspinatus/infraspinatus)

- Upper trapezius and latissimus dorsi

- Thoracic/lumbar erector spinae

- Gluteus medius/maximus and hip extensors

- Forearm flexors/extensors for club control

Collect EMG at high sampling rates (≥1000 Hz), apply a band-pass filter (20-450 Hz), full-wave rectify and compute a linear envelope using a suitable low-pass filter (6-20 Hz) matched to the movement bandwidth.

From Lab to Practice: Drills, Strength Work and Motor-Control Interventions for Coaches and Clinicians

Translational planning means converting kinematic and neuromuscular markers – pelvic-thoracic separation, peak trunk angular deceleration, lead-arm extension and timely glute-to-trunk force transfer – into explicit coaching and rehab objectives. Use field-ready tools (video angle measures, IMUs) alongside clinic-grade tests (isokinetic dynamometry, surface EMG) when available.Prioritize interventions by deficit severity and injury risk: re-establish safe deceleration mechanics before emphasizing maximal clubhead speed; restore intersegmental timing ahead of power progressions.

- Split-contact deceleration drill: practice shortened backswing finishes emphasising a strong lead-hip stop and “land-and-hold” cues to train eccentric hip and trunk braking.

- Towel coupling drill: tuck a towel under the trail armpit during partial-to-¾ swings to preserve shoulder-chest coupling and reduce early arm casting.

- Slow weighted swings: use a light kettlebell or a weighted practice club at ~50% speed to exaggerate proximal-to-distal timing; emphasize axial rotation then controlled arm release.

- Step-rotate balance: step into the lead side on the finish to reinforce stable lead-leg loading and pelvic control.

Strength and conditioning prescriptions should be specific, progressive and tied to observed deficits. Prioritize hip extensors and abductors for power transfer,obliques and transverse abdominis for rotational control,and eccentric shoulder/scapular capacity for deceleration.A typical rehabilitation-to-performance progression is: neuromuscular re-education (low-load, high-control, 2-3×/week); strength phase (moderate load, 3-4×/week); and power/transfer work (ballistic/resisted rotations, 2-3×/week). Objective milestones (for example,restoring single-leg symmetry or trunk rotational-velocity symmetry by ~10-20% improvement) should guide return-to-full-speed practice.

| Exercise | Primary Target | Typical Dose |

|---|---|---|

| Glute bridge | Hip extension | 3×10-15,3×/wk |

| Pallof press | transverse stability | 3×8-12,3×/wk |

| Single‑leg RDL | Hinge control & balance | 3×6-8,2-3×/wk |

| Resisted trunk rotations | Rotational power/control | 3×8-12,2×/wk |

| Eccentric rotator cuff | Shoulder deceleration | 3×8-12,3×/wk |

Motor-control strategies should encourage variability,external focus and gradual removal of constraints so that corrected movement patterns become robust. Implement blocked-to-random practice, externally directed cues (e.g., “drive the hip toward the target”), and faded augmented feedback. Add perturbation and reactive tasks to build adaptable deceleration skills, and evaluate motor learning with retention tests (24-72 hours). Suggested drill set:

- Perturbation finish: a light coach-applied push during follow-through to train reflex stabilization of the trunk.

- Randomized target practice: vary target location and club selection to improve adaptability under changing contexts.

- external-focus video feedback: short clips that emphasize outcomes (ball flight,finish direction) rather than joint angles to support implicit learning.

Integration and progression criteria should be explicit and communicated between coach and clinician. Use objective gates (symmetry indices within ~10-15%, normalized trunk angular deceleration within pre-injury ranges, and pain-free full-velocity swings) as progression milestones. Track IMU-derived sequencing metrics, repeatable deceleration profiles on force plates, and shoulder-scapular endurance to guide return-to-play. Embed maintenance elements – periodic eccentric shoulder work, hip-control refreshers and variability-rich practice – into off-season plans to preserve follow-through mechanics and reduce recurrence.

Q&A

Q&A: Kinematic and Neuromuscular Analysis of Golf follow-Through

(Style: Academic; tone: Professional)

1. What were the primary objectives of this study?

– To map common kinematic sequencing and momentum-transfer behaviors during the golf follow-through and to identify the neuromuscular mechanisms (timing, amplitude, contraction type) that support accurate ball delivery and active deceleration. The goal was to link joint-level motion and muscle activation patterns to performance metrics and injury-risk indicators.

2. How does this study define “kinematic” and “dynamic/kinetic” analyses?

– Kinematic analysis describes motion (positions, angles, velocities, accelerations) without accounting for forces. Dynamic or kinetic analysis examines the mechanical drivers of motion – forces and moments such as ground-reaction forces and joint moments.Both approaches were applied together: kinematics to define sequencing and timing, kinetics to estimate intersegmental moments and momentum transfer.

3. Which participants and swings were examined?

– Samples typically included golfers spanning a range of skill (from low-handicap recreational to elite performers). Swings were standardized by club (e.g., 7-iron and driver) and ball position, and included full-effort swings plus submaximal trials to probe controlled deceleration strategies.

4. What measurement systems and signal-processing procedures were used?

– Three-dimensional motion capture (optical or inertial), synchronized force plates where available, and surface EMG from key muscle groups (trunk rotators/obliques, erector spinae, gluteals, hamstrings, quadriceps, forearm/wrist flexors/extensors and rotator-cuff muscles). EMG signals were band-pass filtered, full-wave rectified and low-pass filtered to obtain linear envelopes, then normalized to MVC before group analysis. Inverse kinematics and inverse dynamics produced joint angles and moments, with attention to model redundancy and coupling in multi-DOF regions like the shoulder.

5. How were joint angles computed given shoulder/arm redundancy?

– Inverse-kinematic solutions used anatomically constrained multisegment models. For redundancy, solution strategies employed optimization criteria (minimizing marker error, joint accelerations, or physiological cost functions) to resolve allowable motions. This approach aligns with analytical methods for redundant systems and enforces physiologically consistent joint limits.

6. What are the principal kinematic findings regarding follow-through sequencing?

– The follow-through retains the proximal-to-distal sequencing from the downswing: pelvis rotation decelerates first, followed by trunk rotation and then the shoulder-elbow-wrist chain. Peak angular velocities propagate from pelvis to thorax to the lead arm and club. Efficient angular-momentum transfer across these links enhances ball speed and directional control, while coordinated trunk-pelvis separation and shoulder-girdle motion facilitate energy transmission and protect distal joints.

7. what neuromuscular patterns support effective follow-through and accuracy?

– Core patterns include:

– Pre-impact bursts in trunk obliques and erector spinae for torso stabilization and rotational set-up.

– Timed concentric activation of prime movers during acceleration,succeeded by eccentric braking in the same or antagonist muscles during follow-through.- Eccentric activity in forearm and wrist muscles to govern club release and limit distal overload.- Coordinated co-contraction around the shoulder and elbow at impact and early follow-through to stabilize joints.

these patterns enable high-power generation alongside controlled deceleration for accuracy and injury prevention.

8. How does active deceleration reduce injury risk?

– Active eccentric muscle actions absorb residual momentum after ball contact, curbing excessive joint rotation and linear accelerations that threaten passive tissues (ligaments, labrum, tendons).This controlled braking lowers peak joint moments and angular velocities at the shoulder, elbow and lumbar spine, reducing cumulative loading that predisposes to overuse injuries.

9. What role does momentum transfer play in accuracy and power?

– Seamless proximal-to-distal momentum transfer times peak segment velocities appropriately, allowing distal segments to reach high tangential speeds at impact.Poor sequencing or mistimed braking wastes energy early, reducing clubhead speed and increasing impact variability, which lowers accuracy.

10. Were kinetic analyses incorporated, and how were forces/moments interpreted?

– Yes. Inverse dynamics using kinematics and external forces estimated joint moments and power flow. Joint power patterns validated the kinematic sequencing: hips and trunk produce positive power during acceleration while trunk and upper limb absorb power (negative work) during follow-through. These kinetic signatures explain how muscles perform concentric and eccentric work to manage rotational energy.

11. How were modeling constraints and couplings handled?

– The musculoskeletal model included explicit kinematic couplings to reflect anatomical linkages (e.g., scapulothoracic behavior, pelvic-hip relationships). Constraint formulations akin to those used in multibody simulation maintained physiological consistency of motion and addressed coupling in multi-DOF regions.

12. What limitations should readers consider when interpreting the results?

– Typical caveats:

– lab conditions (marker sets, club types, surface) may not fully replicate on-course variability.

– Surface EMG can be affected by crosstalk and skin movement; deep muscle signals may not be fully captured.

– Sample composition and size may limit broad generalization.

– Inverse-dynamics outcomes depend on inertial parameter estimates and model assumptions; redundancy resolutions can bias joint estimates.

– Kinematic descriptions alone do not establish causality without kinetic corroboration.

13. What are the practical implications for coaching and rehabilitation?

– Recommendations include:

– Emphasize proximal stability and sequencing drills to reinforce pelvis-to-trunk-to-arm timing.

– Implement eccentric strengthening for trunk, hip extensors/rotators and forearm/wrist muscles to boost braking capacity and reduce injury risk.

– Use motor-control exercises (segment isolation, tempo swings) to reduce timing variability at impact.

– Screen and address ROM limits and asymmetries that lead to compensatory mechanics.- Progress load and velocity carefully to build both concentric power and eccentric braking skill.

14. What future research directions are proposed?

– Future work could:

– Combine wearable sensor arrays with on-course data collection for ecological validity.

– Use high-density EMG and imaging to resolve deep-muscle roles.

– Explore how skill level, prior injury and individual variability shape kinematic and neuromuscular strategies.- integrate neuromuscular simulations and optimization methods to forecast intervention effects, leveraging advanced inverse-kinematic techniques for redundant systems.

15. How should readers place these findings within the biomechanics literature?

– This work frames the follow-through as an integral part of the swing that mediates energy dissipation and accuracy, consistent with broad principles of proximal-to-distal sequencing, momentum conservation and the centrality of eccentric braking. Methodological distinctions between kinematic and kinetic analyses, redundancy handling and kinematic coupling reflect standard biomechanics practice and support a comprehensive mechanistic interpretation.

If you would like, I can:

– Create a concise visual timeline of key timing windows (pre-impact, impact, early follow-through) with dominant muscle actions in each phase;

– Design a practical drill and exercise program derived from the neuromuscular findings; or

– Produce a methods checklist summarizing instrumentation and signal-processing steps for replication.

Wrapping Up

This synthesis links kinematic descriptions and neuromuscular mechanisms of the golf follow-through, showing that coordinated joint sequencing, efficient momentum transfer and active muscular deceleration together support shot accuracy and reduce injury likelihood. The kinematic findings map the spatiotemporal cascade of segment rotations and interjoint timing, while neuromuscular results highlight phased activation and eccentric strategies that absorb residual energy and stabilize the upper limb and trunk. Together, these insights explain how observable motion patterns and underlying control processes combine to produce both performance and protection.Practically, the findings recommend evidence-based coaching cues, targeted conditioning and rehabilitation pathways that prioritize timing, eccentric capacity and multi-segment coordination over isolated joint work. Methodologically, the study underlines the complementary value of kinematic and kinetic/dynamic approaches for a full mechanistic account, and points to computational methods from redundant kinematics as useful analogues for advanced inverse-kinematic modeling of the multi-segment swing.

Limitations include the controlled-lab setting, participant characteristics and the difficulty in extrapolating short-term neuromuscular measures to long-term injury risk.Future studies should expand in-field monitoring, broaden participant samples, and combine kinematic-kinetic-neuromuscular modeling to validate and extend these conclusions. Ultimately, an integrated framework that links precise motion sequencing and active muscular control during follow-through provides a strong foundation for translational work in coaching and sports medicine.

perfecting the Follow-Through: The Biomechanics and Muscle Secrets Behind Better Golf Shots

Alternate headline options

- Perfecting the Follow-Through: The Biomechanics and Muscle Secrets Behind Better Golf Shots

- The Science of the Finish: How Joint Sequencing and Muscle Control Optimize Your Golf Follow-Through

- From Hips to Hands: Momentum Transfer and Active Deceleration for a Consistent Follow-Through

- Power, Precision, Protection: Biomechanical Keys to a Safer, More Accurate Follow-Through

- Swing to Stop: Neuromuscular Strategies That Improve Accuracy and Reduce Injury Risk

- Follow-Through Fundamentals: Unlocking the Kinematic and Neuromuscular Basis of Great Golf Shots

Wich tone would you like?

Pick one and I’ll tailor the article further:

- Technical: Detailed force/kinematics, joint angles, and scientific language (best for coaches and biomechanics students).

- Coach-focused: Practical cues, progressions, and practice plans you can use with students.

- Player-kind: Simple cues, drills, and checklists you can use on the range or course.

Why the follow-through matters (keywords: follow-through,golf swing,accuracy)

the follow-through is not just the pretty finish-it’s the visible outcome of how well you sequenced rotation,transferred momentum,and controlled deceleration. A consistent follow-through is tied directly to better accuracy, predictable clubface control, improved ball flight, and reduced injury risk. Optimizing your follow-through enhances clubhead speed and allows reliable distance control while protecting joints through controlled deceleration.

Core biomechanical principles (keywords: kinematic sequence,joint sequencing,hip rotation)

Kinematic sequence: hips → torso → arms → hands

The ideal kinematic sequence for an efficient golf swing starts with the lower body (hips),progresses through the torso and shoulders,then the arms,and finally the hands and clubhead. This proximal-to-distal sequencing maximizes energy transfer and helps the club release with the correct timing, improving both power and accuracy.

Momentum transfer and weight shift (keywords: weight transfer, balance)

Efficient weight transfer from the trail to the lead leg creates ground reaction forces that feed into hip rotation and spine rotation. Good balance through the finish-ending on the lead foot with a stable base-indicates effective momentum transfer and fewer timing errors that lead to mishits.

Active deceleration and muscle control (keywords: deceleration, eccentric control)

After impact the body must decelerate the club. Eccentric control of the forearms,rotator cuff,lats,and core allows a controlled release and safe finish. Active deceleration stabilizes the joints and prevents uncontrolled forces that cause slices, hooks, or injury.

Primary muscles and joints involved (keywords: core stability, hip rotation, shoulder mechanics)

- Hips/glutes: Drive rotation and create ground force; prime movers early in the sequence.

- Obliques & core: transfer rotational energy and stabilize the spine during deceleration.

- rotator cuff & deltoids: Control the shoulder joint, especially in the follow-through and finish.

- Forearms & wrist extensors/flexors: Manage wrist release and clubface control at impact and afterwards.

- Quadriceps & calves: provide stable platform for weight transfer and balance.

Signs of an inefficient follow-through (keywords: swing faults, clubface control)

- Early collapse of the lead knee or falling back toward the trail leg (poor weight transfer).

- Arms that stop or collapse after impact (lack of momentum transfer or poor sequencing).

- Over-rotated shoulders with a collapsed lower body (reverse sequence).

- Uncontrolled wrist flip or late release causing inconsistent clubface orientation.

- Pain or soreness in the low back, shoulder, or elbow after practice (poor deceleration mechanics).

High-value drills to build a reliable follow-through (keywords: follow-through drills,swing mechanics)

| Drill | Primary focus | Reps |

|---|---|---|

| Hip-Lead step Drill | Proximal initiation & weight transfer | 10-12 per side |

| Slow-Motion finish | Kinesthetic sequencing & balance | 8-10 slow swings |

| Impact Bag/Eccentric Catch | Deceleration control | 6-8 controlled reps |

| Lead-Foot Balance Holds | Finish stability | Hold 5-10s x 5 |

How to do them

- Hip-Lead Step Drill: Start with feet shoulder-width. Take a short step with your lead foot as you start the downswing to encourage hip rotation and early weight shift. Swing through and finish balanced on the lead leg.

- Slow-Motion Finish: Make slow, deliberate swings focusing on the sequence hips → torso → arms → hands. Pause at the finish to check balance and club position (club over lead shoulder).

- Impact Bag / Eccentric Catch: Lightly hit an impact bag or towel to practice absorbing force after impact. Feel the arms decelerate and the core control the torso.

- Lead-Foot Balance Holds: Hit half-shots, step into the finish and hold on the lead foot for 5-10 seconds. This trains finish position and balance under reduced load.

Practice progressions and programming (keywords: practice plan, swing tempo)

Progress drills in load and speed. Start with slow, high-feedback rehearsals, then add tempo, then add full speed with ball. A weekly microcycle could look like:

- 2 range sessions focused on drills (15-25 minutes)

- 1 session of strength/stability (core, glutes, single-leg balance)

- 1 on-course or simulated pressure session (apply the finish to shot shapes)

Warm-up and conditioning to protect the finish (keywords: injury prevention, mobility)

Warming up the hips, thoracic spine, shoulders, and wrists helps you perform an efficient follow-through with less compensatory movement. Include:

- Dynamic hip swings and band-resisted rotations

- Thoracic rotation drills (open-book, 90/90) for upper spine mobility

- Rotator cuff light band work for shoulder stability

- Single-leg balance and glute activation for lead-leg strength

Common technical cues by problem (keywords: swing faults, follow-through fixes)

| Problem | Simple cue | Drill |

|---|---|---|

| Hitting fades/slices | “Rotate hips earlier, release palms” | Hip-Lead Step + Slow-motion Finish |

| Hooking or overdraw | “Check wrist flip, feel passive release” | Impact Bag / Eccentric Catch |

| Loss of distance | “Drive with glutes, complete weight shift” | Lead-Foot Balance Holds |

| Pain after practice | “Reduce speed; strengthen rotator cuff” | Shoulder stability + tempo work |

Case study: A practical example (first-hand experience style)

Player: Weekend golfer, 38, struggles with inconsistent drives and low-back tightness.

- Assessment: Reverse sequencing-upper body dominated, limited hip rotation, and early spinal extension in the follow-through.

- Intervention (8 weeks): Hip mobility drills, single-leg balance, slow-motion sequence practice, and impact-bag deceleration work twice weekly.

- Outcome: More consistent ball flight, improved carry distance by ~12-18 yards on average, and reduced post-round low-back soreness.

Measuring progress (keywords: clubhead speed, accuracy, consistency)

Track these KPIs:

- Clubhead speed (radar or launch monitor)

- Shot dispersion (fairways/green proximity)

- Balance hold time on lead foot

- Pain or soreness rating after practice

Programming checklist before your next range session

- 5-7 minutes dynamic mobility (hips, thoracic, shoulders)

- 10-15 slow-motion sequencing reps

- 10 drill-focused swings (hip-step, impact bag)

- 20-30 full-speed shots applying one finish cue

- Finish with a single-leg balance hold and short rotator cuff band work

SEO tips for coaches and content creators (keywords: golf follow-through, swing mechanics)

- Use target keywords naturally in headings and first 100 words (e.g., “follow-through”, “golf swing”, “kinematic sequence”).

- include descriptive alt text for images-describe the action and technical intent (e.g., “golfer finishing on lead leg with club over shoulder”).

- Use bullet lists and tables for readability; search engines favor structured content.

- Offer downloadable practice plans or printable checklists to increase dwell time and backlinks.

quick-reference drill table (short & practical)

| Drill | One-line purpose |

|---|---|

| Hip-Lead Step | Start downswing with hips to sequence power. |

| Slow-Motion Finish | Groove timing and balance at slow speed. |

| Impact Bag | Train safe deceleration and clubface control. |

| Lead-Foot Hold | Build finish stability and balance. |

Ready to tailor this article?

if you want this rewritten in a specific tone-technical, coach-focused, or player-friendly-tell me which and I’ll produce a tailored version with adjusted cues, deeper kinematic graphs (technical), or simplified practice plans and language (player-friendly).