Optimizing physical preparation for golf requires blending biomechanical understanding with targeted exercise science to boost performance and lower injury likelihood. As the sport increasingly rewards ball speed, carry, and repeatable shot-making, research highlights key mechanical and physiological drivers-proximal‑to‑distal sequencing, pelvis‑thorax separation, angular velocity, force request through the ground, rotational power, and neuromuscular precision-that form the foundation of an effective swing. Simultaneously occurring, an athlete’s ability to exploit these mechanical advantages depends on musculoskeletal capacity: adequate lower‑limb and trunk strength, joint mobility, rapid force production, and stamina to sustain performance across rounds.

Modern investigations using 3D motion capture, force platforms, electromyography, and wearable sensors have clarified how shortfalls in mobility, stability, and intersegmental timing interrupt efficient kinetic‑chain transfer and raise the chance of overuse complaints-most commonly in the lumbar spine, shoulder complex, and wrist. Bringing this evidence into applied programs means focusing not only on building strength and power but also on refining movement quality, applying motor‑learning strategies, using progressive overload appropriately, and individualizing periodization. Intervention evidence shows that multimodal regimens-resistance training, plyometrics, rotational medicine‑ball protocols, and specific mobility/stability drills-produce measurable improvements in clubhead speed, ball velocity, and shot reproducibility when they reinforce swing‑appropriate motor patterns. Recent meta‑analyses report modest but consistent performance gains when strength and rotational power work are combined with technical practice.

This article condenses contemporary biomechanical and physiological research to present practical assessment tools and training strategies designed for golf. It summarizes objective performance measures and screening options,assesses the effectiveness of common training methods,and provides actionable recommendations for program design and load management.It also discusses limitations in the current literature and highlights priorities for future research to better align biomechanics and training for performance enhancement and injury reduction.

Biomechanical Foundations of the Golf Swing: Kinetic Chain, Torque Generation, and Energy Transfer

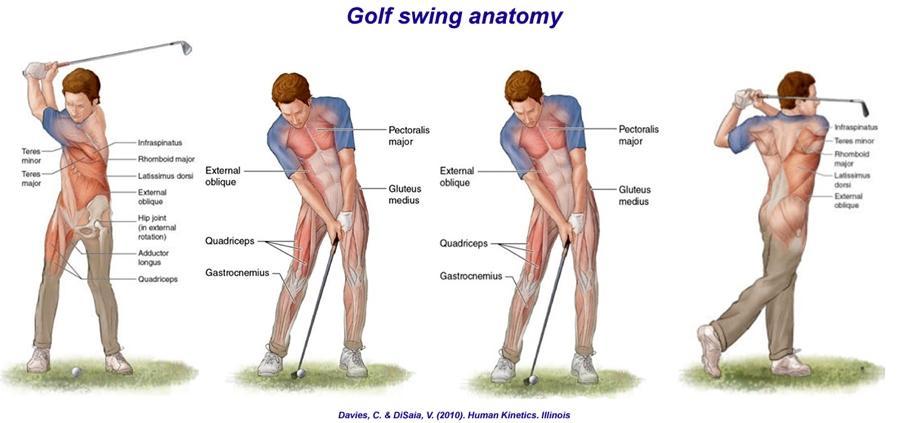

Effective swing mechanics are built on a coordinated kinetic chain in which the feet, hips, torso, arms, and club function as connected segments that accelerate and decelerate in sequence to maximize clubhead velocity. Motion‑capture work repeatedly shows a proximal‑to‑distal activation cascade: the pelvis initiates rotation, followed by the thorax, then the shoulders, elbows and wrists. This ordered timing avoids simultaneous overloading of multiple joints and lets each link operate near its optimal speed and power output. Breaks in this sequence-whether from restricted mobility, setup faults, or faulty motor patterns-typically reduce distance, increase lateral error, or promote compensatory strain patterns.

Rotational torque is central to the swing’s mechanics: rotational moments generated by the pelvis and trunk, resisted through the feet and lower limbs, produce the angular impulse that propels the club. Critically important mechanical inputs include pelvic angular acceleration, thoraco‑pelvic separation (the commonly cited X‑factor), and firm bracing of the lead leg that transforms ground reaction forces into usable rotational torque. Efficient torque production depends on controlled eccentric loading of axial musculature during the backswing followed by a rapid concentric release-harnessing the stretch‑shortening cycle for greater power with efficient energy cost.

Preserving energy as it flows along the chain requires both timing and stability.Mechanically, the aim is to limit intersegmental energy loss by stabilizing proximal links while permitting freer unloading of distal segments; in practice, this equates to stable hip and trunk centers paired with a coordinated wrist release. Coaches and clinicians can track a compact set of biomechanical checkpoints that signal effective energy transfer:

- Sequence: pelvis → thorax → shoulders → hands/club

- Timing window: a short phase of peak torso angular velocity before hand release

- Ground interface: reliable lateral force shift and lead‑leg bracing

- Mobility vs stiffness: sufficient rotational range with controlled axial stiffness

These checkpoints create focused targets for both technical coaching and conditioning interventions.

Putting biomechanical concepts into practice calls for targeted metrics and matching training responses. Use motion‑capture or IMU data and force‑plate outputs to quantify sequencing, segmental velocities, and ground reaction characteristics; complement these with field tests for power and mobility.The table below lists representative metrics, how to interpret them biomechanically, and suitable training priorities, formatted for WordPress editorial use:

| Metric | interpretation | Training Focus |

|---|---|---|

| pelvis→Torso lead (ms) | Sequencing latency | Core timing drills, medicine‑ball throws |

| Peak torso angular vel. (deg/s) | Rotational power | Rotational strength, explosive rotational exercises |

| Lead‑leg vertical GRF (BW) | Ground force transfer | Single‑leg stability work, plyometrics |

| wrist release velocity (m/s) | distal transfer efficiency | Coordination drills, wrist speed development |

Target interventions that restore correct sequencing and limit energy dissipation-improvements in these metrics typically map to higher clubhead speeds, tighter dispersion, and greater resilience across a tournament week.

Movement Assessment and Screening Protocols to identify Mobility, stability, and Motor control deficits

A systems approach to screening recognizes that golf‑specific movement skill emerges from the interplay of joint mobility, segmental stability, and sensorimotor control. Rather than relying on isolated joint measures, practitioners should layer assessments: first identify passive and active range limitations, then test dynamic stability under load, and finally probe task‑relevant motor control using swing‑like tasks. emphasize ecological validity and simplicity-tests should mimic the rotational, single‑leg, and rapid recoil demands of the swing while remaining reliable for repeat measures.

A practical assessment battery combines validated clinical screens with golf‑specific tasks to span the three domains. core elements include:

- Mobility: hip internal/external rotation, ankle dorsiflexion (weight‑bearing lunge), thoracic rotation range

- Stability: single‑leg squat and Y‑Balance for dynamic control, trunk endurance tests (plank/side‑bridge) for lumbopelvic support

- Motor control: select FMS elements, TPI pattern checks, and swing‑analogue tasks such as step‑downs or resisted trunk rotations to inspect sequencing and timing

These can typically be completed within a 20-30 minute appointment and are easily paired with video capture for kinematic review and cueing.

When interpreting results, integrate magnitude, side‑to‑side differences, and movement quality-small, non‑painful asymmetries can be acceptable if safely compensated, while reproducible loss of control or painful ranges should be prioritized for correction. The table below provides conservative practical thresholds for guiding clinical decisions; adjust targets to the athlete’s baseline and competitive objectives.

| Test | Primary domain | Practical threshold |

|---|---|---|

| Weight‑bearing lunge | Ankle mobility | ≈35° dorsiflexion ideal; flag side‑to‑side >6° |

| Hip internal rotation (prone) | Hip mobility | ~30° or more preferred; asymmetry >10° noted |

| Y‑Balance (composite) | Dynamic stability | Interlimb reach diff <4 cm desirable |

| Side plank endurance | Lateral trunk endurance | >45 s per side or progressive target |

- Clinical decision rule: restore pain‑free ranges and reduce major asymmetries before advancing high‑velocity power work; validate sequencing changes with video feedback.

- Monitoring: retest mobility and motor control every 4-8 weeks and stability/endurance every 6-12 weeks depending on phase.

Evidence Based Strength and Power training for Golf Specific Performance Enhancements

Recent evidence emphasizes that both maximal force capacity and reactive force production are central determinants of clubhead speed and consistent shot dispersion. Biomechanical studies indicate that when lower‑limb drive, trunk stiffness, and timely pelvis‑thorax separation are well‑coordinated, the advantages of increased muscular strength translate more effectively into golf‑specific power. Strength sets the upper limit of force production, while targeted power work (improving rate of force development and velocity‑specific output) converts that capacity into higher swing speeds and greater distance without degrading control.

- Olympic‑style lifts (e.g., power clean): cultivate triple extension and high‑velocity force expression

- Medicine‑ball rotational throws: train rapid torso‑to‑arm transfer and angular velocity

- Plyometrics & eccentric loading: enhance stretch‑shortening efficiency and deceleration control

- Unilateral strength and loaded carries: correct asymmetries and support consistent weight transfer

applied programming should follow specificity, progressive overload, and velocity‑based selection principles.Periodized blocks cycle through strength‑focused phases (high load, lower velocity) and power‑conversion phases (moderate loads, maximal intent velocity), with maintenance phases aligned to competition. Objective monitoring-CMJ, velocity tracking, and force‑time profiling-helps adjust volume and intensity and reveals fatigue‑related drops in explosive capacity that could hinder on‑course results or raise injury risk. For many golfers, coordinated strength‑to‑power sequencing yields more transfer than isolated heavy lifting alone.

| Metric | Assessment | target adaptation |

|---|---|---|

| Max Strength | 1RM Back Squat / Deadlift | Raise force ceiling to support powerful drives |

| Explosive Power | Countermovement Jump (CMJ) peak power | Improve rate of force development |

| RFD & Transfer | Isometric mid‑thigh pull (RFD) | Faster force onset for club acceleration |

- Load management tools: RPE, bar‑velocity devices, jump metrics

- Injury mitigation: blend thoracic mobility, cuff resilience work, and eccentric hamstring protocols

- Integration: coordinate heavy and high‑velocity gym sessions with swing work-avoid maximal neuromuscular sessions instantly before critical technical practice

Mobility, Flexibility, and Thoracic Spine Interventions to Optimize Rotation and Reduce Compensatory Patterns

Thoracic mobility plays a pivotal role in rotational efficiency for the golf swing: sufficient segmental extension and axial rotation permit better thorax‑pelvis dissociation and reduce excessive lumbar torsion or shoulder compensation. Limitations in the thoracic region often present as increased lumbar shear, premature lateral flexion, or overactive scapulothoracic motion during transition and the early downswing-patterns that break sequencing and raise cumulative tissue stress. Restoring thoracic motion thus redistributes rotational demand more appropriately, improving energy transfer and diminishing harmful joint moments.

Effective interventions are multimodal, addressing passive restrictions, neuromotor control, and usable range. Useful elements include:

- Thoracic mobilizations – grade‑appropriate posterior‑anterior and rotational techniques to recover segmental mobility.

- Soft‑tissue work – targeted myofascial release for paraspinals, rhomboids, and serratus region to reduce stiffness.

- Active control drills – scapular setting plus thoracic rotation and banded resisted dissociation drills.

- Breath‑driven movement – diaphragmatic breathing to improve rib cage mobility and prepare the thorax for eccentric loading in the swing.

To make mobility gains robust, progressively apply them under increasing load and velocity: move from passive/assisted techniques to unloaded active control, then to loaded rotational rehearsals (cable chops, med‑ball throws), and finally to swing‑tempo integration. Empirically,short daily mobility sessions (10-15 minutes,3-5×/week) combined with 2-3 weekly strength/rotation sessions produce durable improvements and reduce compensatory movement when progressed under supervision.

Ongoing,objective reassessment is critical to direct progressions. the table below lists practical clinical measures and realistic targets common in program design:

| Assessment | Clinical marker | Practical goal |

|---|---|---|

| Seated thoracic rotation | Degrees of rotation without lumbar contribution | ≥45° each side or symmetrical |

| Prone thoracic extension | Ability to clear chest off foam roller | Maintain neutral cervical alignment |

| Loaded chop pattern | quality of dissociation and sequence | Controlled pelvis‑to‑thorax timing at game speed |

Clinical caution is warranted-neurological signs or worsening pain necessitate specialist referral. When interventions are measured, specific, and integrated into the overall program, restoring thoracic function lowers compensatory loading, improves rotational efficiency, and contributes to performance gains while lessening injury risk.

Neuromuscular Coordination and Speed Training for Improved clubhead Velocity and Shot Consistency

Raising clubhead speed and reducing shot variability depend heavily on neuromuscular coordination as much as on raw strength. Gains come from better motor‑unit recruitment, improved rate coding, synchronized intermuscular timing, and refined sensorimotor integration-changes that collectively decrease undesirable variability across the kinematic chain. Clinical neuromuscular work emphasizes thorough motor‑control screening to shape individualized interventions that preserve pattern fidelity.

Training should therefore stress explosive, task‑specific neural adaptations alongside technical practice. Core elements include:

- Ballistic power – medicine‑ball throws and short‑contact plyometrics to enhance rate coding and intermuscular timing.

- Reactive speed – reactive step drills and perturbation tasks to improve rapid sequencing and stability under changing inputs.

- Overspeed and tempo training – controlled overspeed swings (light clubs or assisted modalities) and metronome‑guided tempo reps to subtly shift timing windows without breaking mechanics.

- Eccentric control – deceleration and tempo drills to secure consistent impact positions and limit variability.

Program sequencing typically emphasizes neural adaptations before or alongside increases in load to preserve technical integrity.

Design short training blocks (4-8 weeks) that alternate high‑velocity neural work with consolidation phases. Monitor using objective metrics-radar clubhead speed, dispersion‑smoothed measures, and movement velocity-and escalate clinical review if neurological deficits or marked asymmetries emerge. Rehabilitation and performance staff should coordinate whenever motor control issues are suspected to prevent maladaptive compensation.

| Drill | Primary Target | Typical Load/Prescription |

|---|---|---|

| Short med‑ball rotational throws | Rate coding & sequencing | 3-5 sets × 6-8 reps |

| Reactive step + swing transfer | Reactive stability | 4-6 sets × 4 reps |

| Overspeed assisted swings | Increase clubhead velocity | 8-12 reps, low total volume |

monitoring: evaluate velocity and dispersion weekly, log perceived motor‑control changes, and adjust drills based on measured transfer. Aligning neuromuscular training with on‑course outcomes helps optimize both peak speed and reproducible shot patterns.

Periodization, Load management, and Return to Play Guidelines to Minimize Injury Risk and Maximize Adaptation

long‑range training should be organized into an annual structure that matches physiological aims to technical priorities and competition schedules. Use a hierarchical model-macrocycle (season), mesocycles (preparation, competition, transition), and microcycles (weekly)-to enable progressive overload while maintaining swing mechanics. In golf, programming typically shifts from capacity building (hypertrophy and general strength) to conversion (strength to power/speed) and then to maintenance during the competitive season. Plans must be adjusted for tournament density, travel, and recovery windows to balance gains with durability.

Effective load management blends objective and subjective data to spot maladaptive trends early. Consider a multimodal set of indicators:

- Session RPE and daily wellness scores

- Training volume measures (resistance tonnage, swing counts, practice duration)

- Physiological markers (HRV, resting heart rate, TRIMP)

- Biomechanical exposure (high‑velocity shots, range stressors)

Interpret trends rather than single snapshots; use the acute:chronic workload framework sensibly and always complement it with clinical reasoning rather than treating any single ratio as definitive.

Return‑to‑play should be criterion‑based and progressive, moving from pain‑free baseline function to full competitive intensity. Clearance requires objective symmetry in strength, adequate ROM, and tolerance of incremental technical loads without symptoms. A practical staged progression clinicians can adapt is shown below:

| Stage | key Criteria | Example Progression |

|---|---|---|

| Rebuild | Pain absent at rest; baseline ROM | Low‑load stability and corrective mobility |

| Strength | ≥90% contralateral strength; controlled asymmetry | Resistance training 2-3×/wk, multijoint lifts |

| Power/Speed | Power outputs tolerate submax swings | Med‑ball rotational throws, jump training |

| Sport Reintroduction | Full practice session without symptoms | Graduated on‑course exposure and tournament simulation |

Putting these stages into weekly practice needs deliberate structure and clear interaction across disciplines to both drive adaptation and minimize injury.A representative microcycle might contain two strength sessions (focus on hips/trunk), two speed/power sessions (golf‑specific plyometrics and med‑ball work), one mobility/technique session, and progressive on‑course exposure. Incorporate deload weeks every 4-8 weeks as load dictates, set objective checkpoints at mesocycle ends, and establish immediate modification rules for any new pain or performance drop. Provide athletes with explicit return‑to‑play criteria, incremental targets, and thresholds that trigger medical reassessment to ensure safe, evidence‑based progression back to competition.

Integrating Technology,Monitoring,and Objective Metrics for Individualized Training Prescription and Progression

Best practice is grounded in objective measurement rather than solely subjective judgment. Practitioners should incorporate a multimodal technology toolkit-three‑dimensional motion capture, inertial measurement units (IMUs), launch monitors, force plates/pressure mats, surface EMG, and autonomic sensors (HRV, wearable HR)-to build a extensive biomechanical and physiological profile. Each device yields complementary insight: kinematic sequencing from motion capture/IMUs; kinetic and balance data from force/pressure systems; ball and club performance from launch monitors; and neuromuscular patterns from EMG. Embedding these tools in baseline testing creates reproducible metrics for individualized programming and longitudinal comparison against minimal detectable change thresholds.

Interpretation should emphasize reliability and context: favor metrics with established intra‑ and inter‑session reliability and translate them into functional constructs (hip‑shoulder separation, rotational velocity, RFD, ground impulse) rather than chasing isolated numbers. Convert measurements into decision rules (such as, progress ballistic training when rotational velocity exceeds a certain percentile and RFD is stable). Use normative datasets where available; if not, rely on intra‑athlete z‑scores and control‑chart logic to flag meaningful deviations that warrant load orTechnique adjustments.

Progression frameworks must be data‑driven and support autoregulation. Set explicit metric targets for training blocks (e.g., incremental gains in peak rotational power, maintain swing symmetry within ±5% of baseline) and adopt stopping/deload triggers tied to objective signals (for example, >10% drop in clubhead speed alongside increased lumbar extension excursion, or HRV falling >1 SD from rolling baseline). Blend periodized overload with micro‑adjustments guided by readiness indicators (HRV, jump power, wellness scores, and acute:chronic workload ratios). For return‑to‑play and injury prevention, require convergence across kinematic, kinetic, and physiological measures rather than progressing based on a single improved metric.

Operationalizing this model needs a reproducible data pipeline and coordinated teamwork among coaches, physiotherapists, and sport scientists. Key elements include standardized test protocols, synchronized time stamps, secure cloud storage, and dashboards that convert raw data into actionable flags.The short illustrative table below shows how selected metrics might drive short‑term planning (values are examples):

| Metric | Baseline | 4‑wk Target | Progress Rule |

|---|---|---|---|

| Peak Rotational Velocity (deg/s) | 420 | 450 | Increase load if +6% and RFD stable |

| Clubhead Speed (mph) | 102 | 106 | Advance power drills when +3% |

| Trunk‑Pelvis Separation (deg) | 35 | 38 | Prioritize mobility if below baseline |

- Data quality: ensure device calibration and consistent testing conditions.

- Sampling frequency: match cadence to the metric’s temporal sensitivity.

- Communication: deliver concise, metric‑driven guidance to athletes and coaches.

Q&A

Below is a concise,research‑informed Q&A intended for the article “Optimizing Golf Fitness: Biomechanics and Training.” The style is professional and evidence‑focused. “Optimizing” is used in the common sense of making performance and health as effective as possible.Q1. What does “optimizing golf fitness” mean?

A1. Optimizing golf fitness refers to creating and executing assessment, training, and recovery plans that maximize golf‑specific outputs (clubhead speed, shot repeatability, course endurance) while reducing injury risk. This requires combining biomechanical swing analysis with physiological conditioning (strength, power, endurance, mobility) and data‑driven load and recovery management so gains transfer to on‑course performance.

Q2. Which biomechanical features of the golf swing matter most for training?

A2. Important features include kinematics (segmental rotations, shoulder‑hip separation/X‑factor, trunk tilt), kinetics (ground reaction forces, intersegmental torque), timing/sequencing (proximal‑to‑distal angular velocity progression), and impulse generation (rate of force development). Efficient energy transfer from feet and pelvis through the trunk to the club is central; deficits in mobility, strength, or timing reduce speed and increase compensatory loading.

Q3. Which physiological traits most influence golf performance?

A3. Key attributes include:

– Maximal and explosive strength (lower body, posterior chain, trunk)

– Power and rate of force development (RFD) to translate strength into clubhead speed

– Rotational and anti‑rotation strength for controlled segmental dissociation

– Muscular endurance and general conditioning for consistent performance across 18 holes and tournament weeks

– Mobility (thoracic rotation, hip internal/external rotation, ankle dorsiflexion) to enable efficient mechanics

Q4. How does strength training improve swing outcomes?

A4. Strength training increases the muscular and stabilizing force capacity involved in the swing. When combined with power and speed work, greater maximal strength generally supports higher RFD and increased clubhead/ball speeds. Transfer is maximized when training mirrors sport‑specific movement patterns (rotational, unilateral, triple‑extension) and when power work is layered onto a strength base.

Q5. What evidence‑based design principles should guide a golfer’s program?

A5. Core principles:

– Specificity: emphasize rotational and unilateral movements reflecting swing force vectors

– Progressive overload: incrementally raise load, complexity, or speed

– Periodization: sequence phases for hypertrophy/strength, conversion to power, and in‑season maintenance

– Individualization: adapt to age, sex, injury history, mechanics, and competition calendar

– Transfer sequencing: build strength, convert to power, then integrate with swing practice and on‑course exposure

Q6.Which exercises deliver high value for golf?

A6. High‑transfer choices include:

– lower‑body strength: Romanian deadlifts, single‑leg RDLs, split squats

– Hip power: kettlebell swings, loaded hip thrusts

– Rotational power: medicine‑ball rotational throws/chops, cable woodchops, banded resisted rotations

– Trunk control: Pallof presses/holds

– Upper‑body power/control: push‑press, unilateral rows, controlled deceleration drills

– plyometrics: vertical and horizontal jumps and rotational ballistic throws

Prioritize unilateral and rotational variations to target typical asymmetries and movement demands.

Q7. How should practitioners structure microcycles and mesocycles?

A7. Example:

– mesocycles (8-12 weeks): preparatory (hypertrophy/strength, 4-6 weeks), conversion (strength→power, 3-4 weeks), sport‑specific/peaking (power and technical integration, 2-4 weeks).

– Weekly microcycle: 2-3 strength sessions (heavy→moderate loads), 1-2 power sessions (ballistic/high velocity), 2-3 mobility/stability sessions, plus technical swing practice. In‑season, reduce volume but preserve intensity.

Q8. What objective tests effectively assess fitness and track progress?

A8.common, validated measures:

– Performance: clubhead and ball speed (radar/launch monitor), carry distance

– Power: CMJ, squat jump, medicine‑ball rotational throw

– strength: 1RM squat/deadlift or estimated max; isometric mid‑thigh pull for peak force/RFD

– Mobility: thoracic rotation, hip rotation, ankle dorsiflexion

– Movement quality: single‑leg balance, step‑down test, asymmetry screens

– Biomechanics: 3D motion capture or IMUs and force plates for sequencing and GRF

Select tests that align with training aims and repeat them consistently.

Q9.How should warm‑ups and pre‑shot routines be used?

A9. Warm‑ups should combine light cardiovascular activation,dynamic mobility (thoracic rotations,hip/ankle mobilizations),progressive activation (band rotations,light med‑ball throws),and ramped swings. Pre‑shot routines standardize arousal and preparation-brief neuromuscular priming (one or two explosive med‑ball throws or light swings) can transiently enhance clubhead speed via post‑activation potentiation.

Q10. What injury patterns and risk factors should conditioning address?

A10. Common complaints include low back pain, thoracic/lumbar strain, rotator cuff/labral issues, elbow tendinopathy, wrist injuries, and hip/knee problems. Risk factors include poor thoracic mobility, limited hip internal rotation, weak gluteal activation, asymmetrical loading, excessive practice volume, and inadequate recovery.Conditioning should target mobility, posterior‑chain strength, scapular control, and controlled rotational power while managing volume.

Q11. How should load and recovery be managed to reduce injury risk?

A11. Combine objective and subjective monitoring (sRPE, sleep, soreness, training load, wearable outputs). Progress loads gradually-avoid sudden spikes-periodize around competition, prescribe active recovery (mobility, low‑intensity aerobic), and emphasize sleep and nutrition. Early response to pain or deteriorating movement quality is essential; consider cross‑training and technical adaptations when load must be reduced.

Q12. Are ther age‑ and sex‑specific program considerations?

A12. Yes. Older golfers typically need greater focus on mobility, balance, and maintaining strength/power to counter sarcopenia and preserve sequencing. Females may present relative strength and power differences and greater joint laxity-programs should address trunk and hip control and be scaled to relative capacities. Individualize volume and progression: older athletes often require longer recovery and conservative loading; youth should prioritize movement quality and gradual exposure to load.

Q13. How is transfer from gym to course achieved and maximized?

A13.transfer hinges on specificity, session timing (power work close to swing practice), and neural integration. Maximize transfer by:

– Choosing exercises with similar force vectors, velocities, and sequencing

– Timing power sessions to precede or coincide with technical practice for neural priming

– Using implements (medicine balls, cables) that mimic swing mechanics

– Measuring on‑course metrics (clubhead speed, dispersion) to validate transfer

Q14. What role do biomechanics tools play in program design?

A14. Tools like 3D capture,IMUs,force plates,and launch monitors help detect technical faults,asymmetries,timing inefficiencies,and injurious loads. They support objective baseline assessment, targeted interventions (e.g., improve X‑factor via thoracic mobility and pelvis control), and quantitative monitoring. Practical use balances accuracy, cost, and clinical relevance.

Q15. What practical, evidence‑based advice should coaches and clinicians follow?

A15. Recommendations:

– Perform an initial screen of movement quality, strength, mobility, and swing biomechanics

– Build a foundational strength base before emphasizing high‑velocity power

– Prioritize rotational and unilateral work plus posterior‑chain strength

– Use periodization to align peaks with competition

– Monitor load and recovery; educate athletes about sleep, nutrition, and self‑management

– Integrate biomechanical feedback and track objective performance metrics

Q16. Can you provide a sample 8‑week outline for an intermediate golfer?

A16. Example (8 weeks, 3 gym sessions/wk):

– Weeks 1-4 (Strength): 2×/wk lower‑body/hip strength (3-5 sets, 4-8 reps), 1×/wk upper‑body/core stability (anti‑rotation), daily mobility work

– Weeks 5-6 (conversion): reduce volume, raise intensity; introduce explosive lifts (2-4 sets, 3-5 reps) and med‑ball rotational throws (3-5 sets, 3-6 reps)

– Weeks 7-8 (Power/Sport specific): stress high‑velocity, low‑load power (plyometrics, med‑ball throws, ballistic lifts) and put technical sessions soon after power work; keep one heavy session/wk to maintain strength

Adjust loads and rest according to competition and athlete response.

Q17. What research gaps remain and where should work be directed?

A17.Gaps include long‑term randomized trials directly linking specific interventions to on‑course outcomes and injury incidence, mechanistic studies showing how gym‑based rotational training alters swing kinematics, and predictors of individual responsiveness. Promising areas: wearable analytics for real‑world load monitoring, machine learning for personalized programming, and integrated interventions that combine technical, physical, and cognitive training.

Q18. How should clinicians share and implement program plans with coaches and players?

A18. Use clear,objective screening data to set measurable goals (target clubhead speed,CMJ advancement,ROM increases). Provide prioritized, time‑sensitive action plans that fit practice schedules. Promote interdisciplinary collaboration (coach, S&C coach, physiotherapist) for cohesive progressions. Emphasize adherence, gradual progression, and regular reassessment.

Summary statement

optimizing golf fitness is best achieved through theory‑driven, evidence‑based programs that unite biomechanical diagnostics, progressive strength and power work, mobility and stability interventions, and deliberate load management. Practitioners should individualize prescriptions, measure transfer against on‑course metrics, and collaborate across disciplines to enhance performance while controlling injury risk.

If you would like,I can:

– Convert this Q&A into an expanded FAQ section for publication;

– Draft a detailed 8-12 week periodized program tailored to a specified golfer profile (age,handicap,injury history);

– Compile a short bibliography of principal research on golf biomechanics and training.

optimizing golf fitness is an iterative, multidisciplinary process requiring rigorous assessment, tailored programming, and continuous refinement guided by scientific evidence and field experience. By anchoring training and rehabilitation in biomechanical and physiological principles-and by using objective monitoring and cross‑disciplinary collaboration-practitioners can help golfers achieve lasting performance improvements while reducing injury risk.

Swing Science: Biomechanics and Training to Boost performance and Prevent Injuries

Why biomechanics matters for golf performance

Golf is a skill sport built on efficient, repeatable movement. Understanding golf biomechanics – how the body produces and transfers force through the legs, hips, torso, and arms into the club – helps players and coaches optimize the swing for greater distance, improved accuracy, and fewer injuries. Key biomechanical drivers of a powerful, consistent golf swing include:

- Kinematic sequence – coordinated timing from ground reaction forces through hips, torso, arms and club.

- Rotational power & X-factor – adequate separation between upper and lower torso during the backswing to store elastic energy.

- Ground reaction forces – how effectively the feet and legs generate and direct force into the swing.

- Center of pressure & balance – maintaining balance throughout the swing for consistent contact and swing path.

- Mobility and stability – sufficient hip, thoracic spine, and ankle mobility paired with core stability to control forces.

Physiology behind the swing: muscles, energy systems and adaptations

The golf swing is a short-duration, high-velocity movement that relies primarily on the following physiological elements:

- Fast-twitch muscle fibers – for explosive clubhead speed and acceleration.

- Neuromuscular coordination – rapid recruitment and sequencing of muscles to produce an efficient kinematic chain.

- Muscular endurance – for consistent performance over 18 holes and during practice sessions.

- Versatility and joint range – notably thoracic rotation, hip internal/external rotation, and ankle mobility.

Training should create sport-specific adaptations: more rotational power, better deceleration control (to protect the body), and improved fatigue resistance for late-round performance.

Assessment & screening: find what to train

before programming, screen movement and identify limiting factors in mobility, stability, and strength. Useful assessments include:

- Thoracic rotation test (sitting or standing)

- Hip internal/external rotation and single-leg squat

- Shoulder overhead reach and scapular control tests

- Single-leg balance and hop tests

- Core endurance tests (plank, anti-rotation hold)

Document findings and prioritize deficits that directly affect the swing (e.g., limited thoracic rotation frequently enough reduces clubhead speed and increases low-back loading).

Evidence-based training pillars for golf fitness

1. Mobility & dynamic flexibility

Mobility is foundational for creating the X-factor and safe rotation. key areas: thoracic spine, hips, shoulders, and ankles.

- Thoracic windmills and foam-roll + rotation drills (2-3 sets of 8-12 reps)

- Hip CARs (controlled articular rotations) and 90/90 drills

- Dynamic ankle mobility: banded dorsiflexion and ankle rocks

2. Strength & hypertrophy (base building)

General strength supports force production and joint resilience. Focus on multi-joint lifts and unilateral work to address imbalances.

- Squats and deadlifts variations (2-4 sets × 5-8 reps)

- Bulgarian split squats and lunges (2-3 sets × 6-10 reps)

- Pulldowns/rows and push variations to build balanced upper-body strength

3. Power & rotational speed

Transform strength into clubhead speed with explosive, golf-specific drills.

- Medicine ball rotational throws (standing and kneeling) – 3-5 sets × 4-6 reps

- Explosive step-ups, jump squats or trap bar jumps – low reps, high intent

- Band-resisted swings and overspeed training (with caution) to refine timing

4. Core & anti-rotation stability

A resilient core transfers rotational energy and controls deceleration forces to protect the spine.

- Pallof press variations (3-4 sets × 8-12 sec hold)

- Anti-rotation holds and chops/lifts with medicine ball

- Dead bug progressions and single-leg RDLs for integrated stability

5. Balance, proprioception & ankle/foot strength

Better balance improves contact consistency and weight shift. Integrate single-leg work, wobble-board drills, and gait/foot strengthening.

practical warm-up & pre-round routine

Use a dynamic routine that builds mobility, activation, and rehearsal of the swing pattern. A 10-12 minute pre-round routine might include:

- 5 min light aerobic movement (walking, bike) to raise core temp

- Thoracic rotation reaches (2 sets × 10 reps each side)

- Hip openers / leg swings (front-to-back and side-to-side, 10-12 each)

- Dynamic lunges with reach (8-10 each side)

- Medicine ball standing rotation throws (6-8 each side) at submaximal effort

- 2-4 slow practice swings focusing on sequencing and tempo

Sample 8-week golf fitness microcycle (weekly focus)

| Week | Primary Focus | key Drills/Work |

|---|---|---|

| 1-2 | Mobility & movement basics | Thoracic work, hip CARs, basic strength |

| 3-4 | Build strength & unilateral stability | squats, lunges, rows, Pallof presses |

| 5-6 | Power & speed advancement | Med ball throws, jump work, band swings |

| 7-8 | Sport integration & peak transfer | on-course drills, overspeed swings, simulated rounds |

Sample training sessions by level

Beginner (2-3 sessions/week)

- Mobility 10 min (thoracic, hips, ankles)

- Strength: Goblet squat 3×8, single-leg RDL 3×8, bent-over row 3×8

- Core: Pallof press 3×8 each side

- Finish: 4×8 med-ball rotational throws

Intermediate (3-4 sessions/week)

- Warm-up + mobility

- Strength compound: Back squat 4×6, Romanian deadlift 3×6

- Explosive: Trap bar jumps 3×5

- Rotational: Med-ball side throws 4×6 each

- Core + balance: 3×30s single-leg balance holds with eyes open/closed

Advanced (4-5 sessions/week)

- Periodized strength phases with heavy days and power days

- Olympic lift variations or advanced plyometrics for power

- High-quality overspeed swings and on-course simulation

- Recovery and mobility daily

Injury prevention: common problems and targeted solutions

Golfers commonly experience low-back pain, wrist/forearm issues (golfer’s elbow), and shoulder strains. Prevention strategies include:

- Address mobility deficits – limited thoracic rotation and hip restriction increase lumbar load.

- Build eccentric control – slow controlled lowering in swings and strength lifts reduce stress on tendons.

- Balance training – improves deceleration mechanics and prevents compensatory patterns.

- Load management – stagger practice and training intensity; schedule recovery days.

transfer to the course: bridging the gym-to-course gap

Transferring gains from the gym to lower scores requires deliberate practice. use these approaches:

- Use band-resisted and med-ball swing drills to connect rotational power with swing mechanics.

- Practice with tempo constraints – developing a consistent rhythm improves timing under fatigue.

- Simulate course pressure: perform targeted drills at the end of training when slightly fatigued to build late-round consistency.

- Record ball flight and clubhead speed periodically to quantify performance changes.

Case study: 8-week improvement in distance and pain reduction

Player: 48-year-old amateur with limited thoracic rotation, recurrent low-back stiffness and average driver distance of 245 yards.

- Intervention: 8-week program focusing on thoracic mobility, unilateral strength, and med-ball rotational power (3 sessions/week).

- outcomes: Thoracic rotation increased by ~15-20°,driver speed increased by ~6-8 mph (measured on launch monitor),average distance gained ~20-30 yards,and low-back stiffness subjectively reduced.

- Key takeaway: Addressing the limiting mobility while building rotational power produced measurable transfer to on-course performance.

Common myths and FAQ

“More gym equals more distance” – True or false?

Partly false.Building strength is necessary, but without mobility, coordination and swing-specific power training, extra strength may not translate into distance. The right blend of mobility,strength,and rotational power work is what creates transfer.

How often should I train to see real improvements?

2-4 structured sessions per week combined with daily mobility and on-course practice typically yields consistent improvements in 6-12 weeks. Quality beats quantity – focus on high-intent power work and consistent mobility.

Is overspeed training safe?

When used judiciously and progressed properly, overspeed (lighter club or band-assisted) work can help increase swing speed. Avoid overspeed if you have uncontrolled joint pain or unresolved injuries; consult a coach or clinician first.

Practical tips for coaches and players

- Prioritize assessment. Train what’s limiting the swing first – mobility or stability?

- Use measurable metrics: clubhead speed,ball speed,thoracic rotation degrees,single-leg balance time.

- Keep sessions short and specific: 30-60 minutes focused, and pair gym training with quality range sessions.

- Track recovery: sleep, nutrition, hydration and load management are critical for consistent gains.

Recommended equipment & resources

- Small kit: med ball (4-10 lb), resistance bands, kettlebell or dumbbells, foam roller

- Optional: launch monitor for objective swing speed and carry distance tracking

- Screening tools: smartphone video for kinematic sequence review and simple ROM tests

If you want, I can tailor this article to a specific audience or tone (e.g., weekend golfer, college athlete, senior golfer, or coach) and refine one of the title options above – tell me your preferred audience and tone and I’ll adapt the content and meta tags accordingly.