Optimizing – here used to mean making a system perform at its best – offers a useful framework for examining the physical factors that shape golf performance. modern research characterizes the golf swing as a rapid, multi-segment motor task in which coordinated force generation, precise sequencing between body segments, and accurate timing determine shot outcomes and influence injury susceptibility. Improvements in motion analysis, force-measurement technologies, and muscle performance testing have clarified how elements such as hip-to-shoulder separation, application of ground-reaction forces, trunk rotational stiffness, and lower-limb power interact to produce clubhead velocity and repeatable ball flight. Concurrently, epidemiological and clinical work points to modifiable physical and biomechanical contributors – reduced joint mobility, asymmetric loading patterns, and insufficient strength or endurance – that increase rates of low-back, shoulder, and elbow injuries among golfers.

This review distills recent biomechanical and physiological findings into practical,evidence-informed training recommendations specific to golf. It combines kinetic‑chain principles with modern training approaches - including task‑specific strength and power progress, mobility and stability protocols, neuromuscular control progressions, and periodized load management – to recommend assessment-led interventions that increase performance while lowering injury risk. The emphasis is on translating lab-based discoveries into field-ready protocols, individualizing programs using screening and performance metrics, and flagging persistent knowlege gaps for future investigation. Below we examine the biomechanical basis of the swing, outline key physiological determinants of performance, review training modalities, and offer actionable guidance for coaches, clinicians, and researchers.

Kinetic‑Chain dynamics of the Golf Swing: How Sequencing and Force Production Drive Power

Kinetic‑chain concepts view the swing as a linked sequence of force generation and transmission beginning at the feet and moving through the legs, pelvis, trunk, upper limbs, and finally the club. This cascade converts muscle contractions and rotational impulses into linear and angular kinetic energy. Efficient transmission depends on proximal segments producing stable, high‑speed impulses that are relayed distally with minimal dissipation; when hips or torso are underpowered or mistimed, the arms and hands must compensate, decreasing efficiency and elevating injury risk.

Motion‑capture work consistently demonstrates a proximal‑to‑distal pattern: pelvis rotation peaks first, then the torso, then the upper arm and forearm, and ultimately the clubhead. Predictors of ball speed include peak angular velocities of pelvis and torso and the temporal gaps between these peaks and wrist uncocking or clubhead acceleration. practical biomechanical markers to monitor during training are:

- Ground‑reaction force (GRF) magnitude and rate of force development as load shifts from trail to lead foot.

- Pelvis‑torso separation (the X‑factor) and the rate at which that separation is created and released.

- Timing differentials between peak pelvis velocity and peak clubhead speed (elite swings commonly show lead times in the range of tens to a few hundred milliseconds).

Translating these biomechanical insights into training demands attention to both force capacity and timing precision. Stronger hips,posterior chain,and core expand the potential for force production; neuromuscular timing work and tempo drills convert that potential into transferable clubhead velocity. The table below offers practical targets and straightforward corrective strategies for common kinetic‑chain inefficiencies:

| Deficit | Biomechanical Sign | Training Focus |

|---|---|---|

| Insufficient hip drive | Low GRF, delayed pelvis peak | Loaded lateral lunges and resisted rotational work |

| Reduced X‑factor | Limited pelvis‑torso separation | Thoracic mobility drills and rotational medicine‑ball throws |

| Poor timing/sequence | Early wrist release, limited clubhead speed | Tempo training and delayed‑release swing drills |

Maximizing efficiency requires balancing force production, segmental stiffness, and release timing; thus, programs should combine progressive overload with motor‑control practice that preserves sequencing. Simple on‑course and gym cues: press into the trail foot during the transition,initiate the downswing with a compact,forceful hip shift,allow trunk inertia to pull the arms through,and coordinate wrist **** release with peak trunk deceleration. Wherever possible, coaches should quantify changes with objective tools (force platforms, high‑speed video, validated wearables) rather than depend only on subjective ball‑flight feedback.

Practical Assessment Suite for Golf‑Specific mobility, Stability, and strength

A structured, domain‑targeted test battery produces the most actionable profile for performance development and injury prevention.Assessments should focus on the kinetic‑chain elements central to rotational golf: thoracic rotation, hip internal/external rotation, ankle dorsiflexion, plus proximal stability of the lumbopelvic region and shoulder girdle. Combining qualitative movement screens (single‑leg squat, overhead squat) with quantitative measures (goniometers, inclinometers, force‑platform outputs) helps practitioners identify specific deficits while accounting for natural individual variability in build and swing style.

Field‑friendly tests that support repeat measurement include:

- Thoracic rotation (seated or standing) – measured with an inclinometer or smartphone app; aim for ≈45° per side as a pragmatic target for unrestricted rotation.

- Hip rotation (supine) – passive IR/ER using a goniometer; >10° side‑to‑side asymmetry suggests a mobility or control imbalance needing correction.

- Ankle dorsiflexion (knee‑to‑wall) – practical minimum ~7-10 cm; limited dorsiflexion often links to midfoot collapse and altered weight transfer during the swing.

- Dynamic single‑leg control – Y‑balance or single‑leg squat quality scoring to reveal contralateral deficits in stability and motor control.

Standardize warm‑up and measurement posture to reduce variability across repeated tests.

Strength and power testing should capture both maximal and rotational capacities relevant to clubhead speed and swing tempo. Practical options include:

- Medicine‑ball rotational throw (standing/seated) – distance or velocity across three maximal trials per side as a rotational power proxy.

- Countermovement jump (CMJ) – single or bilateral jump height using a jump mat or validated smartphone app for lower‑limb power.

- Isometric mid‑thigh pull or posterior‑chain 1‑RM tests – assess maximal force that supports sustained loading in the downswing.

Sequence testing so mobility and stability checks precede maximal strength/power efforts, allow 3-5 minutes rest between maximal trials, and record perceived exertion to contextualize results.

Interpreting scores requires mapping deficits to corrective interventions and retest timelines.Reassess mobility/stability every 6-8 weeks and strength/power every 8-12 weeks; use thresholds such as >10% change in power outputs or >5° change in joint rotation to indicate meaningful progress and guide program updates.

| deficit | Key Test | practical Intervention |

|---|---|---|

| Limited thoracic rotation | Seated thoracic rotation (°) | Thoracic mobilizations and rotary stability drills (3×/week) |

| Restricted hip rotation | Supine hip IR/ER (°) | Hip capsule mobilization and glute med activation (4-6 weeks) |

| Poor single‑leg control | Y‑Balance composite | Progressive unilateral strength and proprioception (balance → power) |

Eccentric, Concentric, and Rotational Strength Approaches to Boost Clubhead Speed and Consistency

Specificity of muscle actions matters for improving velocity and repeatability. Eccentric contractions (muscle lengthening under load) control deceleration and store elastic energy; concentric actions (shortening) create the propulsive force that accelerates the club; coordinated transverse‑plane torque transmits that force through the kinematic chain. Training must therefore develop eccentric capacity (to absorb and redirect energy), concentric power (to generate force quickly), and timing/coordination of rotational torque. Each mode influences peak clubhead speed, shot dispersion, and tissue durability when applied with appropriate intensity, tempo, and progression.

well‑designed programs expose golfers to both controlled overload and high‑velocity demands. Effective strategies include slow eccentric loading to build tendon stiffness and deceleration tolerance, explosive concentric work to increase rate of force development (RFD), and integrated rotational exercises that hone proximal‑to‑distal sequencing. Sessions frequently enough mix modalities to promote transfer – for example,heavy eccentric Romanian deadlifts (3-5 reps with a 3-4 s eccentric) followed by high‑intent medicine‑ball rotational throws (4-6 reps). Typical session components:

- Eccentric emphasis: slow single‑leg RDLs, controlled Nordic lowers

- Concentric/power: band‑resisted hip drives, jump squats, explosive sled pushes

- Rotational: Pallof press variations, rotational med‑ball slams, standing cable chops

Periodize these elements so athletes progress from capacity and control toward speed and sport specificity.

Manipulate load,velocity,and neuromuscular timing to balance safety and transfer. Use submaximal heavy loads for eccentric conditioning (≈70-85% 1‑RM with slow eccentrics), low‑to‑moderate loads moved with maximal intent for concentric power (≈20-40% 1‑RM or bodyweight plyometrics), and sport‑specific rotational intensities that emphasize sequencing over isolated strength. Schedule heavier, control‑focused sessions earlier in the week and place high‑velocity, low‑load power work nearer competition to reduce interference with skill execution.

Track specificity and progress with objective tools (bar velocity devices, force plates, or launch monitors) to confirm transfer into increased clubhead speed and tighter dispersion.

| Exercise | Focus | Tempo/Load |

|---|---|---|

| Nordic hamstring | Eccentric control | 3-5 reps, 3-4 s descent |

| medicine‑ball rotational throw | Concentric rotational power | 4-6 reps, maximal intent |

| Pallof press (band) | Anti‑rotation/core sequencing | 8-12 reps/side, 2-3 sets |

| Trap‑bar jumps | Lower‑limb RFD | 3-5 reps, light load |

Periodization and Load Management for Golf: Weekly and Seasonal Conditioning Frameworks

Evidence supports structured manipulation of training variables – volume, intensity, frequency, and exercise selection - to build neuromuscular qualities relevant to the golf swing while limiting injury risk. Common periodization models (linear, undulating, block) vary in how rapidly intensity and focus shift; choice of model should reflect an athlete’s training history, competition calendar, and injury profile. Core principles include progressive overload, specificity toward rotational power and endurance, scheduled recovery (deload weeks), and ongoing monitoring of internal and external load to maintain a productive adaptation‑to‑fatigue balance.

| Phase | Duration | Primary Goal | Key Modalities |

|---|---|---|---|

| Off‑season | 6-12 weeks | build hypertrophy & capacity | Strength work, mobility, metabolic conditioning |

| Pre‑season | 4-8 weeks | Convert strength to power | Heavy lifts, Olympic derivatives, rotational power drills |

| In‑season | Competitive blocks | Maintenance & peaking | Low‑volume strength, power taps, on‑course simulation |

| Transition | 1-3 weeks | Active recovery & rehabilitation | Low‑intensity cross‑training and mobility |

At the weekly microcycle level, a reproducible template translates the macro plan into usable sessions. A sample microcycle for a competitive amateur:

- Day 1 – Lower‑focus strength: multi‑joint lifts emphasizing the posterior chain, 3-5 sets at moderate intensity.

- Day 2 – Mobility & technical work: thoracic rotation, hip mobility, and low‑intensity range drills.

- Day 3 – Power & speed: rotational med‑ball throws, jump/power work, and velocity‑based swings.

- Day 4 – Active recovery: low‑intensity cardio, soft‑tissue work, restorative modalities.

- Day 5 – Upper/rotational strength: anti‑rotation core, loaded carries, unilateral strength.

- Weekend – On‑course specificity: simulated competition play, short‑game focus; modulate intensity before events.

This structure provides targeted stimuli for force production and rotational mechanics while protecting recovery windows needed for skill consolidation.

Operational load management blends objective and subjective tools: session RPE, training impulse metrics, swing counts, and, where available, IMUs or velocity devices to quantify external load. Use a cautious acute:chronic workload approach when increasing swing volume or adding high‑intensity power work and schedule deloads every 3-6 weeks or after load spikes. Always individualize progression based on baseline tests (strength, power, mobility), ongoing feedback from coaches and medical staff, and objective recovery markers (sleep, HRV, soreness).

Preventing Injuries: Movement Screening and Focused Corrective Programs for golf‑Related Conditions

Movement screening is the bridge from assessment to intervention. Combine quantitative ROM measures, functional movement assessments, and task‑specific swing analysis to isolate deficits in mobility (thoracic extension, hip rotation), stability (pelvic control under rotation), and intersegmental timing. Use reproducible thresholds and objective tests to identify mechanical dysfunctions rather than relying solely on symptom reports; this allows for corrective work that addresses the mechanical drivers of injury while maintaining performance demands.

Clinicians must recognize mechanical overload versus pathologic presentations that need specialist referral – for example, progressive neurogenic signs consistent with lumbar spinal stenosis or peripheral nerve entrapment such as carpal tunnel syndrome require medical evaluation. For common golf musculoskeletal issues – mechanical low‑back pain, rotator cuff tendinopathy, medial epicondylalgia, and wrist overuse – a graded, criterion‑based corrective exercise program reduces recurrence and improves tolerance to playing loads.

High‑value corrective priorities are concise, progressive, and ordered by the most limiting deficit identified on screen. key elements:

- Mobility: restore thoracic extension and hip rotation to permit safe angular displacement.

- segmental stability: anti‑rotation core and pelvic control to reduce shear and torsion on spinal structures.

- Rotator cuff & scapular control: eccentric and isometric loading to manage tendinopathy and deceleration demands.

- Sequencing retraining: motor‑control drills that reestablish lower‑limb drive, trunk energy transfer, and upper‑limb deceleration timing.

Prescriptions should define dose (sets,reps,tempo),objective progression criteria (pain‑free range,quality repetitions,load increases),and clear return‑to‑swing milestones.

An effective pathway: baseline screening → prioritized corrective block → reassessment at pre‑specified intervals → integration into swing‑specific training when criteria are met. Monitor outcomes using objective movement scores, pain during/after activity, and load tolerance to guide adjustments.

| Pathology | Key Screening | Targeted Correction |

|---|---|---|

| Lumbar mechanical LBP | Rotary stability, hip extension ROM | Glute activation and anti‑rotation core work |

| Shoulder impingement / RC tendinopathy | Scapular control, pain‑free overhead reach | Rotator cuff eccentrics and scapular stabilization |

| medial epicondylalgia | Resisted wrist flexion & grip tests | Eccentric forearm loading plus proximal chain strengthening |

Plyometrics, Reactive Drills, and GRF Optimization: Translating Reactive Strength to the Swing

Recent biomechanical evidence underscores that rapid force production must be synchronized with precise pelvic‑to‑torso‑to‑arm sequencing. Enhancing the stretch‑shortening cycle and improving rate of force development (RFD) contributes directly to clubhead velocity; this requires targeted work on reactive strength and expression of ground‑reaction force. Integration here means combining plyometrics, reactive tasks, and GRF modulation into a coherent, sport‑specific progression. The key physiological drivers of transfer are task specificity, neuromuscular timing, and modulation of intersegmental stiffness.

- Plyometric base: progressive bilateral and unilateral jumps emphasizing vertical and rotational impulses.

- Reactive drills: fast perturbation responses and rapid direction changes to reinforce anticipatory stabilization.

- GRF coaching: foot placement and force‑vector cues to optimize horizontal and vertical impulse during transition and downswing.

Structure progressions to build eccentric‑concentric competency first, then move to high‑velocity, short‑contact‑time tasks. Examples include: soft‑landing depth jumps emphasizing controlled deceleration; rotational medicine‑ball throws promptly followed by countermovement jumps; and single‑leg hop‑to‑stabilize drills replicating lead‑leg loading. Monitor progression with objective criteria – short‑latency RFD improvements, reduced ground‑contact times, and preserved trunk‑to‑pelvis sequencing under load. Prioritize movement quality and transferability when selecting drills.

| Metric | Unit | Practical Benchmark |

|---|---|---|

| Relative peak GRF | N·kg⁻¹ | Progressive increase vs baseline (e.g., +10-20%) |

| RFD (0-200 ms) | N·s⁻¹ | Clear upward trend across 4-8 weeks |

| Ground contact time (plyo) | ms | Reduction while preserving control |

Embed risk‑reduction and long‑term resilience into implementation: use criterion‑based progressions to introduce high‑impact loads, prioritize eccentric strength and landing mechanics to lower tibial and femoral stress, and match footwear and surface to manage GRF. Include scheduled neuromuscular recovery (sleep, load modulation, low‑intensity stabilization) and use swing‑validated cues so that reactive gains are realized on the course. Safety checklist:

- Screen tendon health and address tendinopathy before frequent plyometrics.

- Apply fatigue thresholds to avoid breakdown in landing mechanics.

- Maintain bilateral/unilateral capacity to support the sport’s inherent rotational asymmetry.

Objective Monitoring, Technology Integration, and Return‑to‑Play Frameworks for Teams

Employ multimodal monitoring that pairs wearable IMUs, force plates, and high‑speed capture with player‑reported outcomes and functional tests. Core variables to track include:

- Kinematic: peak trunk rotational velocity, lag angle, pelvis‑thorax dissociation.

- Kinetic: peak vertical and medial‑lateral GRFs, rate of force development.

- Neuromuscular: asymmetry indices, eccentric control (hamstrings/hip external rotators), and RFD.

- Player‑reported: pain scores, confidence, and golf‑specific function questionnaires.

embed objective thresholds into a transparent, criterion‑based return‑to‑play (RTP) decision matrix to reduce subjectivity. the example table below provides illustrative decision points; clinicians should adapt thresholds to the individual and context.

| Metric | Typical RTP Threshold | Clinical Note |

|---|---|---|

| Clubhead speed | ≥ 90% of pre‑injury value | Progress with graded full‑effort swings |

| Trunk rotational velocity | ≤ 10% side‑to‑side asymmetry | Assess using IMUs or motion capture |

| Force plate asymmetry | < 15% asymmetry | Include single‑leg RFD testing |

Implementing monitoring effectively requires an interdisciplinary workflow: establish preseason baselines, perform serial assessments through rehabilitation, and use algorithmic dashboards to flag deviations from expected recovery. Favor criterion‑based progression,planned deloading and reloading phases,and structured communication between therapists,coaches,and athletes. Use technology to inform, not replace, clinical judgment – align device outputs with assessments of movement quality, pain behavior, and on‑course demands.

Q&A

Optimizing (here meaning “making the most of”) a golfer’s physical profile requires fusing biomechanical understanding, physiological conditioning, and evidence‑based program design. The following Q&A is written for practitioners, researchers, and advanced coaches seeking applied, research‑aligned guidance.

1. What is meant by “golf‑specific fitness”?

– Golf‑specific fitness describes the collection of physical capacities (strength, power, mobility, stability, endurance, and neuromuscular control) trained to maximize golf performance (clubhead speed, accuracy, consistency) while reducing injury risk.The concept emphasizes transferring general physical qualities into swing‑relevant movement patterns, velocities, and neural control strategies.

2. Why is biomechanics central to golf fitness?

– Biomechanics pinpoints movement patterns and force‑time profiles that underlie effective swings (sequencing, angular velocities, GRFs). Translating these findings guides targeted interventions (rotational power,anti‑rotation control) that are more likely to influence swing outcomes than non‑specific conditioning.

3. Which biomechanical features most strongly influence outcomes?

– Key determinants include: (a) proximal‑to‑distal sequencing; (b) peak angular velocities of pelvis and torso; (c) ground‑reaction force magnitude and direction; (d) X‑factor and X‑factor stretch; and (e) consistent swing plane and timing. Together, these shape clubhead speed and shot repeatability.

4. How does the kinematic sequence affect power generation?

– An effective kinematic sequence flows from larger proximal segments to smaller distal ones (hips → trunk → shoulders/arms → club), enabling efficient energy transfer and maximal clubhead velocity while reducing compensatory loads. Early arm dominance or mistimed sequencing reduces efficiency and increases joint stress.

5. Which physiological qualities should be prioritized?

– Priorities include maximal lower‑body and posterior‑chain strength, rotational power, RFD, thoracic mobility, hip IR/ER range, anti‑rotation core strength, unilateral stability, and metabolic resilience for prolonged play. Relative emphasis varies with level (elite vs recreational) and training age.

6. How should strength and power be periodized?

– Suggested macrostructure:

– Off‑season: hypertrophy → max strength (3-6 months) to build capacity.

– Pre‑season: convert strength to power and speed (6-12 weeks) with RFD and rotational med‑ball work.

– In‑season: maintain strength,emphasize velocity and recovery.

– Microcycles: 2-4 resistance sessions/week depending on calendar; include 1-2 power sessions. Progress load then velocity to transfer to swing speed.

7. Which exercises transfer well to the swing?

– High‑transfer options: rotational med‑ball throws, Olympic derivatives or safer variants, Pallof presses, hip/glute strengthening (deadlifts, hip thrusts, split squats), single‑leg perturbation training, and thoracic mobility work. Select exercises for movement similarity and perform at appropriate velocities.

8.How to integrate mobility and motor control?

– Sequence: (1) identify mobility limits (hip, thoracic, ankle); (2) apply targeted mobility and neuromuscular techniques; (3) activate key movers (glutes, serratus, rotator cuff); (4) progress to loaded, high‑velocity patterns that demand restored range and control. Emphasize thoracic rotation and hip IR/ER for separation and sequencing.

9. What are common golf injuries and their mechanical drivers?

– Common presentations: low‑back pain, wrist strains, elbow tendinopathy, and shoulder issues. Drivers include repetitive high‑torque rotations, poor sequencing (increased arm loads), limited hip/thoracic mobility leading to compensatory lumbar rotation, and weak eccentric control during deceleration. Technique and load management are central mitigators.

10. How can training reduce injury risk while improving performance?

– Tactics: correct mobility deficits, strengthen posterior chain and lumbopelvic control, train eccentric deceleration capacity, apply progressive loading with adequate recovery, and monitor pain and load to individualize progression.

11. Which assessment tools are recommended?

– Lab options: 3‑D motion capture, force plates, high‑speed video, and launch monitors. Field tools: validated IMUs, radar for club/ball speed, CMJ mats or apps, IMTP or isometric strength tests, med‑ball throw distance, single‑leg balance tests, and screening tools (Y‑Balance). Pair objective metrics with player‑reported outcomes (RPE,HRV,pain).

12. what metrics indicate transfer to on‑course performance?

– Objective indicators: higher clubhead and ball speed, increased carry distance, and preserved or improved shot dispersion. Kinematic improvements (better sequencing, higher segmental velocities) captured via motion analysis or validated wearables. Subjective signs: perceived swing ease and durability across rounds.

13. How to prescribe load/intensity for power development?

– Phase approach:

– Strength: 4-6 sets of 3-6 reps at ≥85% 1‑RM to build force capacity.

– Power: moderate loads at maximal intent and ballistic movements (low‑to‑moderate loads,high velocity).

– Emphasize RFD using ballistic and Olympic derivatives or safer alternatives, and adjust volumes to competition and recovery needs.

14. Are there guidelines for training frequency?

– General guidance:

– Strength: 2-4 sessions/week based on phase and athlete.

– Power: 1-3 sessions/week, often integrated with strength work.

– Mobility/activation: daily brief work, targeted sessions 2-4×/week.

– Adjust frequency to balance adaptation and recovery.

15. How to individualize for youth, masters, and elite players?

– Youth: focus on movement quality, motor learning, progressive loading; avoid maximal loading early.

- Masters: prioritize joint‑friendly strength (eccentric control),mobility,and recovery; limit high‑impact plyometrics.

– Elite: emphasize specificity,precise periodization,detailed monitoring,and marginal improvements across technique,fitness,and recovery.

16. Practical coaching cues for biomechanical improvement?

– Use sequencing and rhythm prompts (e.g., “lead with the hips,” ”let the torso pull the arms”), stress intent and velocity in power work, and favor external focus cues (e.g., aim to throw toward a target). Pair cues with objective feedback (launch monitor,video).

17. How to monitor fatigue and recovery?

– Combine wellness questionnaires, session RPE, HRV trends, sleep tracking, short performance tests (CMJ, med‑ball throws), and pain reports.Modify load based on trend data rather than single‑day fluctuations.

18. Research limitations and open questions?

– Gaps include few long‑term randomized trials linking specific training to on‑course outcomes,inconsistent metrics across studies,and limited ecological validity of lab work. Future work should test longitudinal interventions, validate wearable tech in the field, examine neural adaptations to rotational training, and profile individual responses.

19. How to evaluate a golf fitness program academically?

– Use mixed methods: pre/post quantitative measures (clubhead speed, ball metrics, kinematics, strength/power tests), injury incidence, and validated patient‑reported outcomes. Include control/comparison groups where possible and transparently report training dose, compliance, and participant characteristics.

20. Immediate practical takeaways for clinicians and coaches?

– Perform structured biomechanical and physical assessments.

– Prioritize thoracic and hip mobility and strengthen the posterior chain and anti‑rotation core.

– Use periodized programming: build strength, convert to power, then maintain.

– Emphasize specificity (rotational velocity and sequence) and monitor recovery and performance.

– Tailor programs to age, injury history, and the competitive calendar.

Summary statement

Optimizing golf‑specific fitness requires aligning biomechanical knowledge with progressive, specific training that develops strength, power, mobility, and motor control while managing load and recovery. Evidence supports building capacity first (strength and mobility), then prioritizing velocity and sequencing to achieve transfer to the swing. Continued longitudinal research is needed to refine dose‑response relationships, long‑term outcomes, and individualized prescriptions.

Recent context note: measurement studies and tour data in 2024-2025 place average PGA Tour driver clubhead speed near ~121 mph for the field, with elite power specialists exceeding 125-130 mph; small increases in clubhead speed (e.g., 2-4%) can meaningfully affect carry distance and scoring, underscoring the practical value of targeted conditioning paired with technical work.

Conclusion

optimizing golf fitness calls for an integrated, evidence‑driven approach that links biomechanical analysis with physiological conditioning and sport‑specific training. Biomechanics clarify the kinematic and kinetic drivers of an efficient swing, and targeted programs in strength, power, mobility, and motor control turn those drivers into measurable performance gains. Periodized planning, individualized assessment, and ongoing monitoring are essential to maximize performance while minimizing injury risk.

for practitioners and researchers,the priority is translational rigor: apply validated assessment tools,use progressively overloaded and task‑specific training stimuli,and adapt interventions to each golfer’s technical profile,physical capacity,and competitive timetable. Interdisciplinary collaboration between biomechanists, strength and conditioning specialists, coaches, physiotherapists, and sports scientists will accelerate development of robust, practical protocols.

Future research should continue clarifying causal links between modifiable physical qualities and on‑course outcomes, test long‑term effects of integrated training models, and validate scalable, real‑world methods.Aligning scientific inquiry with coaching practice will help the field move toward its central aim: make golf‑specific fitness as effective and efficient as possible to boost performance while protecting athlete health.

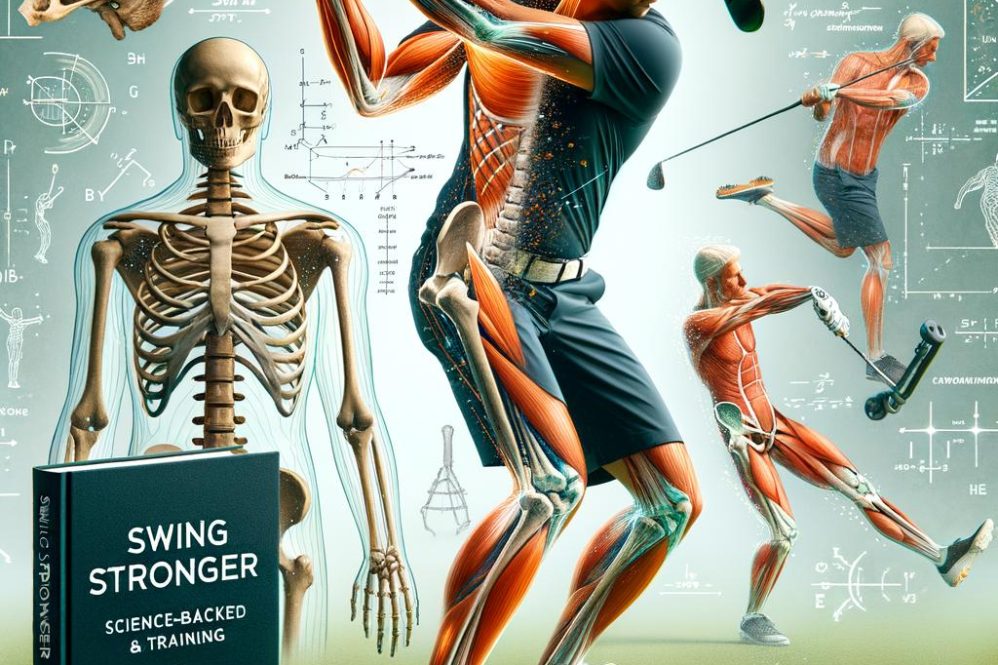

Swing Stronger: Science-Backed Biomechanics & Training for Better Golf

Here are some engaging title options – my top picks are marked:

- Swing Stronger: Science-Backed Biomechanics & Training for Better Golf (Top pick)

- Drive Further, Hurt Less: The Biomechanics of Golf Fitness (Alternate top pick)

- Golf Fitness Unlocked: Biomechanics, Physiology & Targeted Training

- Power, Precision, Longevity: Optimize Your Golf Fitness

- The Golfer’s Blueprint: Training & Biomechanics for Peak Performance

- Play Smarter, Swing Stronger: A Scientific Guide to Golf Fitness

- From Drive to Finish: Evidence-Based Fitness for a Better Swing

- Total-body Golf Fitness: Move Better, Swing Faster, Stay Injury-Free

- Science of the Swing: Improve Distance and Accuracy with Biomechanics

- Fit for the Fairway: Evidence-Based Training to Boost Your Game

- Elite Golf Fitness: Integrating Physiology, Mechanics, and Training

- Biomechanics to Birdies: Practical Training for a More Efficient Swing

Why biomechanics and physiology matter for golf performance

Golf is a rotational, multi-joint skill that depends on efficient sequence, mobility, and power transfer from the ground through the pelvis, trunk, and arms to the clubhead. Integrating biomechanics (how your body moves) with exercise physiology (how your muscles and energy systems perform) delivers training that increases clubhead speed,improves accuracy,reduces fatigue,and lowers injury risk.

Key biomechanics concepts every golfer should understand

- Kinetic chain & sequencing: Efficient force transfer starts at the feet and travels through hips, core and shoulders to the club – timing is critical.

- X‑factor (shoulder-to-pelvis separation): Create stored elastic energy by rotating the shoulders more than the hips on the backswing; manage thoracic mobility and hip restriction to optimize this safely.

- Ground reaction force (GRF): Effective weight shift and leg drive create vertical and horizontal forces that add distance; training single-leg strength and reactive capacity helps.

- Angular velocity & sequencing: Peak rotational speed is most effective when distal segments accelerate after proximal segments (proximal-to-distal sequencing).

- Center of pressure & balance: Stable transitions during the swing (addressing sway and over-rotation) preserve strike consistency.

Physiology fundamentals relevant to golf

- Energy systems: Golf primarily uses the ATP-PCr system for individual shots and short sprints of effort (power), with aerobic systems important for recovery across 18 holes.

- Muscle qualities: Strength (max force),power (force × velocity),muscular endurance (repetitive shots,walking the course),and mobility/stability are all needed.

- Neuromuscular control: Improving motor patterning and proprioception translates gym gains into better swing mechanics.

- Recovery & fatigue management: Nutrition, sleep and active recovery sustain performance across rounds.

Assessment – measure before you train

Testing identifies limiting factors so training is targeted. Use simple, golf-specific assessments and, when available, combine with motion analysis or a TPI/Titleist/physical therapist screen.

- Mobility: Hip internal/external rotation, thoracic rotation, shoulder ROM (degrees or simple screenshots)

- Stability & balance: Single-leg stance with eyes closed, Y‑Balance test

- Strength: 1-3 rep max for major lifts (deadlift, squat) or submax tests; single-leg Romanian deadlift

- Power: Medicine ball rotational throw distance, 3‑second single-leg hop

- Swing metrics: Clubhead speed, ball speed, smash factor, launch angle (launch monitor)

Targeted training components

Design each training session to bridge the gap between the gym and the course. The four pillars below should be present across a weekly program.

1) Mobility & motor control

- Thoracic rotation drills (quadruped thoracic rotation, banded T-spine rotations)

- Hip mobility (90/90 drills, active straight leg raise, lunge with rotation)

- Shoulder and scapular control (banded external rotation, Y/T/W raises)

- Integrate movement into swing-prep drills – mobility plus motor patterning.

2) Stability & core integration

- Anti-rotation drills: Pallof press, half-kneeling chop/ lift with cable

- Single-leg balance and loaded carry progressions (farmer carry + anti-rotation)

- Choose exercises that force the body to resist unwanted rotation while allowing safe transfer of force.

3) Strength – hips, posterior chain, legs, and upper body

- Compound lifts: deadlifts, split squats, hip thrusts to build force production

- Upper body: rows, push variations, rotator cuff strengthening to stabilize the lead arm and shoulder

- Train unilateral strength for stability during weight shift and impact.

4) Power and speed – translate strength to clubhead speed

- Rotational medicine ball throws (variable distances and angles)

- Contrast training: heavy strength sets followed by explosive swings or throws

- Reactive drills and short sprints for neural drive; jump variations for vertical power

Golf-ready warm-up & pre-shot routine

Efficient warm-ups prime mobility, increase core temperature, and activate the neuromuscular pattern for the swing. Aim for 8-12 minutes pre-round and 3-6 minutes pre-shot on the tee.

- Dynamic mobility circuit: leg swings, banded shoulder circles, thoracic rotations

- Activation: mini-band glute walks, single-leg bridges

- Speed reps: 6-10 half-swings at 75-90% speed, 1-2 full swings with an easy target

- Pre-shot breathing and visualization to reduce unnecessary tension

Sample 8‑week golf-specific program (3 sessions/week)

Phases: Week 1-3 (Foundation), Week 4-6 (Strength), Week 7-8 (Power & On-course transfer).

| Week | Focus | Session split (3x/wk) |

|---|---|---|

| 1-3 | Mobility & Motor Control | Lower: squat pattern,single-leg; Upper: rows + band work; Core: anti-rotation |

| 4-6 | Strength & Load | Lower heavy: deadlift/split squat; Upper: push/pull; Conditioning: tempo carries |

| 7-8 | Power & Transfer | Plyos/medicine ball throws; contrast swings; on-range speed sessions |

Example single session (Strength phase)

- Warm-up: 8 minutes mobility + band activation

- Deadlift variation: 3×5 (moderate-heavy)

- Split squats: 3×8 per leg

- One-arm row: 3×8 per side

- Pallof press: 3×10 per side

- Accessory: band external rotation 2×15

- Finisher: 2×6 medicine ball rotational throws per side

Injury prevention & common risk areas

- Low back: often due to poor hip mobility and over-rotation. Address hip ROM, glute strength, and core anti-extension capacity.

- Lead shoulder: stabilize scapula and rotator cuff; avoid excessive overload during training.

- Knee pain: check single-leg strength and landing mechanics; reduce valgus collapse and uncontrolled rotation under load.

- Gradual progressive overload and balanced programming reduces overuse injuries – alternate heavy days with mobility/recovery sessions.

Transfer drills - bridge gym gains to the course

practice drills that mimic swing speed and the timing of the kinetic chain.

- Medicine-ball rotational throws to golf target (progress from short to long toss)

- Step-and-swing: step into shot to emphasize ground force and correct weight transfer

- Tempo swings: reduce overswing and focus on sequence, then add speed

- Band-assisted full swings: use light resistance to train acceleration through impact

Case study (practical example)

Player: 45-year-old amateur, 12 handicap, complains of reduced distance and occasional low-back stiffness.

- Assessment: limited left hip internal rotation, poor single-leg balance, moderate thoracic stiffness.

- Intervention (12 weeks): focused hip mobility (90/90 and dynamic lunge rotations), glute strengthening (hip thrusts, split squats), anti-rotation core work, and medicine ball rotational throws twice weekly.

- Outcome: clubhead speed +4-6 mph, reduced low-back soreness, better consistency with driver.

Practical tips for golfers and coaches

- Measure and track metrics (clubhead speed,mobility ROM,medicine ball throw) every 4-6 weeks.

- Train swing speed with intent – quality of movement beats quantity.

- Prioritize movement quality and pain-free range before adding load.

- mix on-course practice, range speed sessions, and gym training for balanced progress.

- Schedule recovery: sleep, hydration, and soft-tissue work (foam rolling/massage) are part of training.

If you wont titles tailored for beginners, elite players, or SEO keyword groups (e.g., “golf fitness for seniors,” “increase swing speed,” “TPI golf training”), tell me which audience and I’ll refine the title and meta tags to match.