Optimizing-defined as “to make as perfect, effective, or functional as possible” (Merriam‑Webster)-is a foundational objective for contemporary performance enhancement in sport. In golf, the swing constitutes a complex, coordinated sequence of neuromuscular and biomechanical events in which small alterations to timing, segmental sequencing, or force request can produce significant changes in distance, accuracy, and injury risk. this article examines the theoretical and empirical basis for optimizing golf swing biomechanics,situating the discussion within a framework that emphasizes objective measurement,mechanistic understanding,and translational application to coaching and athlete growth.

Drawing on methods from biomechanics, motor control, and data science, the review synthesizes kinematic, kinetic, and electromyographic approaches to quantify swing performance, and it evaluates emerging technologies-three‑dimensional motion capture, inertial measurement units, force plates, and machine‑learning analytics-that enable high‑resolution assessment and individualized feedback. Emphasis is placed on performance‑relevant outcome metrics (e.g., clubhead speed, launch conditions, dispersion) and on biomechanical determinants (e.g., pelvis‑thorax separation, ground reaction force timing, angular velocity profiles).By integrating current evidence with practical considerations for assessment and intervention, the article aims to provide a roadmap for researchers, coaches, and practitioners seeking to apply rigorous, data‑driven strategies to enhance golf swing efficiency, maximize performance, and mitigate injury risk.

Principles of Biomechanical efficiency in the golf Swing

Efficient movement in the golf swing arises from an optimized kinetic chain in which energy is generated, transferred, and dissipated in a continuous proximal-to-distal sequence. Proper sequencing ensures that large, proximal segments (thorax, pelvis) initiate motion and that smaller, distal segments (forearm, wrist) multiply angular velocity rather then generating primary power. Disruptions to this sequence-such as early arm release or delayed hip rotation-create energy leakage, reduce clubhead speed and increase mechanical stress on joints. Quantifying and restoring correct sequencing is thus central to performance optimization.

Ground interaction and lower-limb mechanics provide the foundational force for the entire swing. Effective use of ground reaction forces (GRF) through controlled weight transfer and timely hip drive produces a stable base and increases net system impulse. Maintaining a balanced center of mass over a dynamically shifting base of support preserves postural integrity and enables higher rotational velocities with reduced shear forces at the lumbar spine. coaching interventions should emphasize coordinated ankle, knee and hip function to maximize GRF utilisation.

Rotational mechanics-particularly trunk-pelvis separation and torque management-govern the swing’s power ceiling and injury risk.Achieving an optimal separation angle (commonly referred to as X-factor) while preserving safe ranges of motion enables higher elastic return and angular momentum. Technical and conditioning cues that enhance these qualities include:

- Maintain postural stiffness through the midline to enable efficient torque transfer.

- Delay wrist release to preserve distal velocity multiplication.

- Prioritise hip rotation before excessive lateral sway to protect the lumbar region.

These cues support measurable improvements in clubhead speed and shot consistency.

Neuromuscular control and load distribution are critical for both performance and longevity. Optimising motor patterns reduces co-contraction inefficiencies and distributes mechanical load across larger musculature, limiting tendon and joint overload. The following concise table aligns key biomechanical variables with expected performance outcomes and clinical considerations:

| Biomechanical variable | Performance / Clinical Implication |

|---|---|

| Kinetic sequencing | ↑ clubhead speed; ↓ compensatory shoulder load |

| Ground reaction utilization | Improved stability; greater impulse transfer |

| Trunk-pelvis separation | Higher rotational power; increased lumbar demand |

Translating biomechanical principles into practice requires targeted assessment, progressive conditioning and instrumented feedback. Objective metrics-such as temporal sequencing indices, GRF profiles and intersegmental angular velocities-should guide individualized interventions.Strength and mobility programs must be periodized to enhance the specific force-velocity characteristics of the swing, while technique drills should reinforce efficient motor patterns under progressive task constraints. By aligning training, technique and monitoring with these biomechanical principles, practitioners can systematically raise performance while mitigating injury risk.

Kinematic Chain coordination and Sequencing for Optimal Power Transfer

Efficient power transfer in the golf swing emerges from a coordinated kinematic chain in which motion is generated and transmitted sequentially from the lower limbs through the trunk and into the club. Biomechanically,this requires precise timing of segment rotations and controlled intersegmental forces so that angular velocity peaks progress in a proximal‑to‑distal order. When sequencing is intact,ground reaction forces are converted into trunk torque,which the hips and torso then modulate to amplify clubhead speed while minimizing energy leaks and pathological joint loads.

Key temporal elements of an optimal sequence can be conceptualized as discrete, interlinked phases:

- Lower‑body initiation: weight shift and pelvic coil create the first large torque impulse;

- Trunk acceleration: controlled unwinding of the torso stores intersegmental elastic energy;

- Shoulder and arm transfer: arms harness trunk rotation while maintaining lever geometry;

- Wrist release and club acceleration: distal amplification of angular velocity culminating at impact.

Precise phase overlap (not pure isolation) is critical-each segment should begin accelerating before the previous segment has fully decelerated to preserve momentum flow.

Mechanistically, optimal transfer relies on coordinated joint moments, timely muscle activation patterns, and exploitation of the stretch‑shortening cycle in key musculature (glutes, obliques, scapular stabilizers, forearm extensors). **Intersegmental torque transfer** and conservation of angular momentum maximize clubhead velocity; conversely, premature release of distal segments or asynchronous muscle firing dissipates energy as heat or unnecessary joint stress. Quantifying peak angular velocities and their temporal offsets (e.g., pelvis → thorax → arms → club) provides objective markers for technical refinement.

| Phase | Typical Fault | Performance / Injury result |

|---|---|---|

| Transition | Early arm dominance | reduced torque, lower clubhead speed |

| Downswing (pelvis) | Under‑rotation | Decreased energy transfer; lumbar overload |

| Release | Premature wrist uncocking | Inconsistent impact; increased distal radioulnar strain |

Coaching and training should target the kinematic chain with integrated interventions:

- Motor pattern drills emphasizing delayed wrist release and maintained lever length;

- Ground‑force feedback (force plates or wearable inertial sensors) to train timely weight shift;

- Strength and mobility programs focused on hip rotational strength, thoracic extension, and scapular control;

- Plyometric progressions to enhance stretch‑shortening efficiency in the posterior chain.

Combining biomechanical assessment with targeted corrective exercises accelerates reliable sequencing adaptations while reducing cumulative tissue load.

Ground Reaction Force Application and Lower Body Mechanics

ground-centered force application is the primary mechanical determinant of energy transfer during the swing: the magnitude, direction and timing of the **ground reaction force (GRF)** vector directly influence resultant clubhead velocity. Vertical and horizontal GRF components interact with segmental inertia to create proximal-to-distal momentum; when the vertical impulse is high and the horizontal shear is appropriately timed, the lower extremity functions as a stable launch platform rather than a dissipative anchor.Quantitative studies correlate increases in peak resultant GRF (normalized to body mass) with measurable gains in ball speed, underscoring the need to consider vector orientation and also peak magnitude in technique refinement.

Efficient lower-kinetic-chain sequencing requires coordinated hip, knee and ankle actions that precede and condition torso rotation. The desirable pattern begins with controlled **lead-side stabilization** and trail-side drive: early trail hip extension and external rotation produce a barreling action of the pelvis, followed by reactive lead-hip loading and a brief co-contraction phase across the knees to create a rigid platform. EMG and motion-capture analyses indicate that a 40-80 ms lead of proximal hip torque relative to upper-trunk rotation optimizes energy transfer while reducing decelerative loads on the lumbar spine.

Foot-ground interaction governs center-of-pressure progression and determines whether produced forces are transmitted or dissipated. coaching and training should target observable, reproducible mechanics through simple cues and exercises:

- Wide but athletic stance to increase lateral base of support and allow efficient medial GRF.

- Progressive lateral weight shift from trail to lead foot through the downswing to concentrate GRF under the lead midfoot.

- Active lead leg block (knee flexion-to-extension) timed to coincide with peak hip rotation.

- Controlled heel-rise on the trail foot to assist ankle plantarflexion and augment horizontal impulse.

These practical elements are essential for reproducible force application under variable on-course conditions.

From an injury-prevention perspective, maladaptive loading patterns at the lower extremity often manifest as excessive valgus moments at the knee or asymmetric pelvic shear. Corrective emphasis should combine mobility with capacity: restore hip internal rotation and ankle dorsiflexion to allow natural squat mechanics, and develop eccentric strength in the hamstrings and gluteal complex to absorb decelerative forces. Rehabilitation-focused metrics-rate of force development, single-leg stability indices, and contralateral asymmetry thresholds-provide objective criteria to progress players from corrective work back to performance training while minimizing cumulative tissue stress.

| Metric | target | suggested Drill |

|---|---|---|

| Peak resultant GRF | ~2.0-2.5 × body mass | Lateral drive med-ball throws |

| COP shift (trail→lead) | 10-18 cm | Single-leg weight-transfer hops |

| Pelvic rotation | 40-60° from address | Seated trunk-rotation with band |

Use these benchmarks as a framework for objective assessment and intervention design; coupling measured targets with specific drills accelerates skill acquisition while preserving tissue integrity.

Torso Rotation, Pelvic Tilt, and Spinal Stability: Balancing Mobility and Control

Efficient transfer of kinetic energy through the golf swing depends on precise interplay between thoracic rotation and pelvic orientation. A controlled separation between the pelvis and the thorax-frequently quantified as the intersegmental rotation differential or “X‑factor”-generates elastic energy and contributes to clubhead velocity. However, maximizing separation without sufficient neuromuscular control increases shear loads on the lumbar spine; therefore, optimal performance requires a coordinated strategy that couples **transverse‑plane mobility** in the thorax with **frontal‑ and sagittal‑plane control** at the pelvis.

Spinal stabilization is essential to permit high angular velocities while minimizing injurious compressive and shear forces. Maintaining a functional neutral spine throughout the swing preserves intervertebral congruence and allows eccentric deceleration of rotational forces during the downswing. Key mechanisms include anticipatory **co‑contraction of deep core stabilizers** (transversus abdominis, multifidus) and graded eccentric activity of the obliques and erector spinae to control axial rotation and resist excessive lumbar extension.

Training must therefore balance targeted mobility with progressive stability challenges to translate physiologic gains into swing mechanics.Effective interventions emphasize specificity, motor control, and load management, with an emphasis on incremental exposure to rotational speed and plane‑specific forces. Representative emphases include:

- Thoracic mobility drills: controlled rotations, foam‑roll thoracic extensions to increase transverse range while preserving scapular and cervical alignment.

- Hip/pelvic control exercises: disassociation drills (seated/standing pelvis‑thorax separations) and single‑leg stance progressions to refine lumbopelvic rhythm.

- Core stability progressions: anti‑rotation and anti‑extension loading, loaded pallof presses, and low‑velocity rotational chops for feedforward control.

- Speed integration: graded overspeed swings with reduced load (shortened shaft or lighter club) followed by return to full swing under monitoring.

| Anatomical Component | Primary Function | Training Focus |

|---|---|---|

| Thorax (T‑spine) | Axial rotation and segmental dissociation | mobility drills, thoracic extension control |

| Pelvis / Hips | Load acceptance and pelvic tilt regulation | Gluteal activation, hip internal/external ROM |

| Lumbar spine | Stability under rotational and shear loads | bracing strategies, eccentric control |

| Deep core | Feedforward stabilization and intra‑abdominal pressure | Timed activation, anti‑rotation work |

Translating these biomechanical principles into on‑course performance requires objective monitoring and progressive overload. Employ video kinematic analysis and wearable inertial sensors to quantify thorax‑pelvis separation, pelvic tilt angles, and trunk angular velocity; use these metrics to individualize progression and set thresholds for return‑to‑play following lumbar strain. clinicians and coaches should prioritize drills that reproduce swing‑specific loading patterns while limiting peak lumbar shear during early training phases, thereby optimizing both **performance** and **injury resilience** through a data‑driven, periodized approach.

Club Path, Face Angle, and Wrist Mechanics: Techniques for Consistent Ball Flight

Precise interaction between the club’s travel path and the clubface orientation at impact governs initial ball direction and the axis of spin; therefore, quantifying both variables is basic to reproducible outcomes. The term club path denotes the vector of the clubhead relative to the target line at the instant of impact, while face angle describes the angular orientation of the clubface relative to that same line. When the face is open or closed relative to the path, the resulting sidespin produces curvature (draw/fade) and influences dispersion; when the face and path align within tight tolerances the launch direction becomes the dominant determinant of shot shape. Empirical studies and launch‑monitor data indicate that a sub‑3° variance in face‑to‑path angle materially reduces lateral dispersion for mid‑iron and driver strikes.

Wrist mechanics act as the fine‑control system that modulates dynamic loft and instantaneous face rotation in the final quarter of the downswing. Controlled wrist hinge, timely unhinging, and the minimization of uncontrolled supination/pronation at release are essential to prevent late face twisting. Kinematic chaining that preserves proximal stability (torso and lead arm) while allowing distal adjustment (lead wrist and forearm) produces consistent impact conditions; conversely, excessive independent hand action increases the variability of the face angle by several degrees. Training emphasis should thus prioritize coordinated timing over isolated strength in the wrists and forearms.

Technical interventions to stabilize face‑to‑path relationships should be simple,measurable,and repeatable. Use the following practical checkpoints as part of a structured practice session: • Alignment rod placed parallel to the intended target line to verify swing arc and toe alignment; • Impact bag drills emphasizing square face contact and proper launch direction; • Tempo‑controlled half‑swings with a metronome to synchronize wrist release to body rotation. These constraints reduce degrees of freedom and accelerate the formation of robust motor patterns that translate to full swings.

Objective feedback is indispensable. Modern training should incorporate a combination of launch monitors (track face and path at impact), high‑speed video (to inspect wrist angles and shaft lean), and wearable IMUs (to quantify rotational sequencing and hand speed). Key metrics to monitor include: face‑to‑path differential (degrees), clubhead speed (m/s or mph), and spin axis (degrees). Maintaining a target band-commonly ±2° for face‑to‑path in pursuit of neutral flight-enables targeted corrective cues and accelerates progress by focusing practice on measurable error reduction.

From a coaching and motor learning perspective, progression should move from high‑constraint, low‑variability drills toward variable, game‑like practice that fosters adaptability. begin with blocked repetitions to ingrain the desired impact geometry, then transition to variable practice and randomized conditions to improve transfer under pressure. Employ a constraints‑led approach-altering ball position, club selection, or target width-to elicit self‑organized solutions that preserve optimal club path and face control. Emphasize evidence‑based cues (e.g.,lead arm stability,delayed wrist release) and quantify advancement with periodic re‑testing to ensure retention and on‑course applicability.

Quantitative Measurement and Motion Analysis Using Wearables and High-Speed Cameras

Quantitative measurement in golf-swing research integrates wearable inertial sensors and high-speed optical imaging to produce objective, reproducible kinematic and kinetic descriptors. These systems provide direct measurements of trunk and limb orientations,angular velocities,and temporal sequencing that underpin the mechanical determinants of ball-flight outcomes. When deployed within a controlled testing protocol, combined sensor-camera systems permit cross-validation of parameters such as clubhead speed, peak hip-shoulder separation, and timing of peak angular velocities, enabling robust comparisons across athletes and interventions.

Wearable technology-primarily **inertial measurement units (IMUs)**, pressure insoles, and electromyography (EMG) arrays-delivers continuous, field-capable data streams critical for applied coaching. Typical wearable-derived metrics include:

- Angular velocity of pelvis and thorax (deg/s)

- Segment orientation (quaternion or Euler angles)

- Ground reaction trends from pressure insoles (load transfer timing)

- Muscle activation onset and amplitude from EMG

These measures are particularly valuable for in-situ monitoring as they capture representative swings outside the laboratory while preserving temporal fidelity when sample rates exceed 200 Hz.

High-speed cameras-either marker-based or markerless-complement wearables by providing high-resolution spatial trajectories and visual verification of movement patterns. Modern systems operate between **240-1000 frames per second**, with shutter speeds and multiple-view calibration optimized to minimize motion blur and parallax. Markerless machine-vision models have matured sufficiently to estimate joint centers and segment orientations, while multi-camera marker-based setups remain the gold standard for laboratory-grade positional accuracy, particularly when combined with force plate data for inverse dynamics.

Data integration requires careful preprocessing to ensure analytic validity. Common steps include synchronized time-stamping across devices, low-pass filtering (e.g., 4th-order Butterworth with cutoffs determined by residual analysis), and sensor-fusion algorithms (Kalman or complementary filters) to reconcile IMU drift with optical pose.Subsequent calculations produce kinematic sequences (e.g., distal-to-proximal angular velocity peaks), joint moment estimates via inverse dynamics, and reproducibility metrics (intra-class correlation coefficients) that inform whether observed changes reflect true performance adaptations or measurement error.

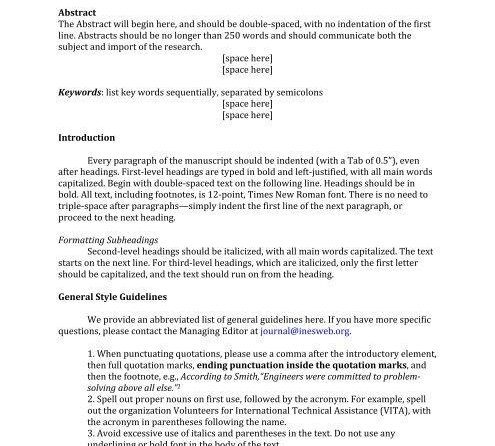

For practitioners implementing quantitative motion analysis, pragmatic choices balance fidelity and feasibility.Below is a concise reference for typical system specifications and expected utility:

| Modality | Typical Sampling | Primary Use |

|---|---|---|

| IMU | 200-1000 Hz | Field kinematics, timing |

| High-speed camera | 240-1000 fps | Spatial trajectories, clubhead verification |

| Force plate / insoles | 1000 Hz | Ground reaction timing / load transfer |

Suggestion: integrate wearables for ecological validity and high-speed optics for spatial accuracy, apply standardized filtering and synchronization protocols, and report sensor specifications alongside outcome metrics to support interpretation and reproducibility.

Data-Driven Training Protocols and Progressive Load Management

Effective optimization of the golf swing through targeted training requires a structured, evidence-based approach that couples biomechanical assessment with progressive load management.By treating the athlete as a dynamic system, practitioners can quantify tolerance and adaptation using objective markers (e.g., peak clubhead speed, trunk rotation velocity, ground reaction force asymmetry) and then prescribe staged increases in mechanical demand. This approach emphasizes **systematic progression**, monitoring of internal and external load, and pre-defined decision rules that trigger modification of training stress when thresholds are exceeded.

Core variables to monitor should be selected for sensitivity to both performance and injury risk and can include:

- External output: clubhead speed, ball launch metrics, shot dispersion

- Biomechanical load: peak torques, angular velocities, kinematic sequencing indices

- Neuromuscular state: rate of force development, reactive strength index, fatigue scores

- Recovery and readiness: resting HRV, subjective wellness, sleep quality

Progressive loading is best implemented with clear micro- and macrocycle structures, where intensity, volume, and specificity are varied according to adaptation signals. Practically, this entails planned increments in swing-specific load (e.g., weighted clubs, velocity-focused swings, repetition schemes) interspersed with deload periods and targeted recovery modalities. Equally critically important is robust **data governance**: standardized data capture protocols, transparent metadata, and education for practitioners to ensure reproducibility and ethical handling of athlete data, aligning with contemporary open-data and stewardship principles.

| Week | Session Intensity | Key Metric Target | Recovery Focus |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 (Baseline) | Low (60%) | Establish baseline clubhead speed | Mobility + Sleep hygiene |

| 2 (build) | Moderate (75%) | +3% peak velocity,stable kinematic sequence | Active recovery + HRV monitoring |

| 3 (Peak) | High (90%) | Max sustainable velocity,controlled dispersion | Cold water immersion,reduced volume |

| 4 (Deload) | Very Low (50%) | Retention of power,reduced fatigue markers | Full recovery,technique refinement |

Advanced implementation leverages analytics pipelines that synthesize sensor streams (IMU,force plates,launch monitors) into actionable dashboards and automated alerts. Decision-making frameworks should use statistical rules (e.g., rolling averages, control charts, z-scores) to distinguish true adaptation from measurement noise, and incorporate **autoregulatory** mechanisms so that session prescriptions respond to real-time readiness. reasonable safeguards-consent procedures, secure storage, and practitioner training-ensure ethical use of athlete data while enabling longitudinal learning and continuous improvement.

Translating Biomechanical Insights into Practice Through Drills, Feedback Metrics, and Coaching Strategies

Laboratory-derived kinematic and kinetic variables must be reframed as explicit, trainable objectives on the driving range and practice green. Prioritization begins with a concise set of performance indicators-**pelvic rotation velocity**, **thorax-pelvis separation (X‑factor)**, **sequencing peak times**, and **ground reaction force symmetry**-each translated into observable movement qualities or target values. Practitioners should adopt an evidence-informed hierarchy that balances injury risk reduction (e.g., lumbar shear minimization) with performance gains (e.g., increased clubhead speed), thereby converting complex biomechanical descriptors into a small number of actionable coaching outcomes.

Training content should be organized into progressive modules that move from perceptual-motor scaffolding to full-speed, context-specific execution. Early phases emphasize motor control and constraint manipulation (reduced swing amplitude, slower tempo, external focus) while later phases reintroduce variability and competitive constraints. Each module must include clear performance criteria for progression, defined in both qualitative descriptors (e.g., “consistent pelvis-to-shoulder dissociation”) and quantitative markers (e.g., target IMU‑derived rotation rates).

- Drill: Medicine-ball rotational throw – develops elastic trunk rotation and segmental sequencing.

- Drill: Impact-bag contact – teaches forward shaft lean and impact compression.

- Drill: Alignment-rod tempo swings – enforces desired swing plane and controlled transition.

- Progression principle: increase velocity and situational variability only after biomechanical targets are met in low-load conditions.

Objective feedback is essential to close the perception-performance gap. Adopt a multimodal measurement strategy combining easy-to-deploy tools (IMUs, portable launch monitors, high-speed video) with periodic lab-grade assessments (force plates, 3D motion capture) when available. Use concise feedback metrics for practice: **peak pelvis angular velocity**, **time-to-peak pelvis vs. thorax**, **vertical ground reaction force impulse**, and **clubhead speed at impact**. Provide athletes with clear thresholds for success and error bands for safe practice; real-time auditory or haptic cues are valuable for reinforcing temporal sequencing, whereas visual post-trial feedback supports structural adjustments.

| Metric | Device | Practical target (example) |

|---|---|---|

| Peak pelvis angular velocity | IMU | 900-1,200°/s |

| Pelvis→thorax sequencing lag | High-speed video / IMU | 20-40 ms |

| Vertical GRF impulse (lead foot) | Portable force plate | 0.6-0.9 Ns/kg |

Coaching must integrate motor-learning principles and clinician-style risk management. Employ analogical cues to encourage global coordination, variable practice schedules to promote adaptability, and error-clamp scenarios to preserve safe joint loads. Prioritized interventions should be embedded within periodized microcycles that align technical work with physical conditioning (hip mobility,rotational power) and recovery. adopt a continuous-monitoring loop: assess baseline biomechanics, set SMART targets, implement drills with objective feedback, and reassess to iterate-this closed-loop framework ensures that biomechanical insight is systematically converted into durable performance improvements and reduced injury probability.

Q&A

Q: what does “optimizing golf swing biomechanics for performance” mean in an academic context?

A: in an academic context, “optimizing” denotes the systematic process of making a system as effective or efficient as possible (see optimize: “to make as effective, perfect, or useful as possible” [1]). Applied to golf swing biomechanics, it involves identifying, measuring, modelling, and modifying the mechanical and physiological determinants of the swing to maximize objective performance outcomes (e.g., clubhead speed, accuracy, repeatability) while minimizing injury risk and physiological cost.

Q: What are the primary biomechanical determinants of an effective golf swing?

A: Key determinants include coordinated kinematic sequencing of body segments (proximal-to-distal transfer), range of motion and intersegmental timing (e.g., pelvis-thorax separation or “X-factor”), ground reaction force generation and transfer, effective center-of-pressure control, joint torques and power production (hip, torso, shoulder), and precise clubhead and clubface kinematics at impact (velocity, path, loft, and face angle). Muscle strength,rate of force development,and neuromuscular coordination underpin these mechanical variables.

Q: What metrics should researchers and practitioners measure to evaluate swing performance?

A: Core metrics include clubhead speed, ball speed, smash factor, launch angle, spin rates, clubhead path, face angle at impact, kinematic sequence timing (e.g., peak angular velocities of pelvis, trunk, arm, and club), ground reaction force magnitudes and temporal patterns, center of pressure travel, segmental joint angles and angular velocities, and joint moments/power via inverse dynamics. Reliability and ecological validity of each metric should be considered.

Q: Which measurement technologies are most appropriate for biomechanical analysis of the golf swing?

A: Common technologies: optical motion-capture systems (high spatial/temporal resolution for kinematics), inertial measurement units (IMUs) for field-based kinematics, force plates and pressure mats for ground reaction forces and center-of-pressure, instrumented clubs and launch monitors (radar/photometric) for club and ball metrics, and electromyography (EMG) for muscle activation patterns. Choice depends on the research question,required precision,and ecological constraints.

Q: how is time-series kinematic data analyzed to extract meaningful features?

A: Typical steps: preprocessing (filtering, gap-filling), event detection (address, top of backswing, impact), time normalization (percent of swing), extraction of discrete features (peak angular velocities, ranges), and computation of derived variables (kinematic sequence indices, joint powers). Techniques such as principal component analysis, functional data analysis, and cross-correlation can characterize inter-segment coordination and variability.

Q: What is the kinematic sequence and why is it critically important?

A: The kinematic sequence describes the temporal order and relative timing of peak angular velocities in a proximal-to-distal chain (typically pelvis → trunk → lead arm → club). An optimal sequence maximizes energy transfer and clubhead speed while minimizing excessive joint loads. Deviations in sequence timing are associated with reduced performance or compensatory mechanics that may increase injury risk.

Q: How do ground reaction forces and lower-limb mechanics contribute to swing performance?

A: The lower limbs generate and redirect forces to create rotational moments and stabilize the kinetic chain. Efficient use of the ground (timed vertical and horizontal force impulses, weight shift patterns, and center-of-pressure control) supports effective generation of torque and contributes to higher clubhead speeds. Force plate data can reveal timing and magnitude patterns linked to performance and asymmetries linked to injury or inefficiency.

Q: What role do joint ranges of motion and mobility deficits play?

A: Adequate mobility (hip rotation, thoracic rotation, shoulder ROM) permits optimal preloading and separation between pelvis and trunk, facilitating elastic recoil and power generation. Deficits can force compensatory motion elsewhere (e.g.,increased lumbar rotation),reducing efficiency and increasing injury risk. Mobility assessment guides targeted interventions to restore functional ranges.

Q: How can strength and conditioning be tailored to improve swing biomechanics?

A: Training should target sport-specific strength,power,and rate-of-force development in the hips,trunk,and shoulders,and emphasize rotational stability and anti-rotation capacity. Exercise selection and periodization should be informed by identified deficits (e.g., unilateral hip strength work for imbalance, medicine-ball rotational throws for power and sequencing).Transfer to swing mechanics should be verified via biomechanical reassessment.

Q: What analytical methods support data-driven optimization (statistical and computational)?

A: Methods include regression and mixed-effects models to identify predictors of performance, principal component and cluster analyses to classify swing patterns, time-series and functional data analyses for coordination, machine learning (supervised models) for prediction and pattern recognition, and musculoskeletal modeling and inverse dynamics for internal load estimation. Model validation using cross-validation and out-of-sample testing is essential.

Q: How can practitioners balance maximizing performance and minimizing injury risk?

A: Use a risk-benefit framework: quantify performance gains from a technique change and estimate internal loads/peak moments associated with that change. If a modification yields marginal performance gains but substantially increases joint loading,choice strategies (e.g., mobility improvement, strength training) should be prioritized. Longitudinal monitoring of load, pain, and functional capacity supports safe progression.Q: What are pragmatic steps for coaches to integrate biomechanical analysis into practice?

A: 1) Define clear performance objectives; 2) Collect baseline data with feasible tools (IMUs, launch monitors, video); 3) Identify key deficits or levers (sequencing, mobility, force production); 4) Implement targeted interventions (technical drills, strength/mobility programs); 5) Re-assess using the same metrics and iterate. Emphasize ecological validity by testing under representative conditions (on-course or realistic practice settings).Q: What are limitations and common pitfalls of biomechanical optimization in golf?

A: Limitations include measurement error, lab-to-field transferability, overreliance on single metrics, ignoring inter-individual variability, and confounding effects of equipment or environmental conditions. Coaches must avoid one-size-fits-all prescriptions and consider motor learning principles: small, incremental changes, sufficient practice, and contextual interference to ensure retention and transfer.

Q: How should researchers handle inter-individual variability and ecological validity?

A: Adopt mixed-methods and hierarchical statistical frameworks that model individual baselines and responses. Use representative task constraints and on-course assessments when possible. Report both group-level effects and individual response patterns, and test interventions across multiple contexts to ensure robustness.

Q: What future directions and technologies show promise for optimizing swing biomechanics?

A: Advances include real-time biomechanical feedback via IMUs and machine-learning algorithms, portable pressure-sensing insoles, markerless motion capture for field assessments, personalized musculoskeletal simulation to predict internal loads and optimal coordination patterns, and integration of multimodal data (kinematics, kinetics, EMG) with longitudinal monitoring for adaptive training prescriptions.

Q: How should performance outcomes be validated following an optimization intervention?

A: Use objective external metrics (ball speed,carry distance,dispersion,scoring outcomes) and internal metrics (joint loads,muscle activation patterns) assessed pre- and post-intervention with controlled or randomized designs where possible. Monitor retention and transfer over time and in varied conditions to confirm practical utility.

Q: What ethical and practical considerations apply to data collection and athlete monitoring?

A: Ensure informed consent, data privacy, and secure storage. Avoid excessive monitoring that may induce anxiety or overtraining.Be transparent about limits of predictive models and ensure that recommendations consider athlete health, long-term development, and personal goals.

Q: Summary: What is the evidence-based pathway to optimize golf swing biomechanics for performance?

A: Conduct precise and ecologically valid measurement; identify biomechanical levers linked to objective performance; apply targeted interventions (technical, mobility, strength) informed by individualized data; use robust statistical and computational tools to model effects; iteratively reassess and adapt while balancing performance gains with injury risk mitigation.

References and terminology note: The term “optimize” is used here consistent with its lexical definition as making something as effective or useful as possible [1]. For applied work, integrate peer-reviewed biomechanics, motor control, and sports-science literature to substantiate specific protocols and thresholds.

Closing Remarks

the analytical optimization of golf swing biomechanics requires the integration of precise measurement, principled biomechanical modelling, and context-sensitive coaching. Empirical analyses of kinematics, kinetics, and neuromuscular coordination can reveal the mechanical determinants of distance and accuracy, while individualized data-driven interventions translate those determinants into practical technique and training modifications. Practitioners should prioritize reliable measurement protocols, longitudinal monitoring, and iterative feedback loops to ensure that observed changes reflect durable performance improvement rather than short‑term variability.

For applied settings, multidisciplinary collaboration between biomechanists, coaches, strength and conditioning specialists, and sport technologists will accelerate the translation of laboratory findings into on‑course gains.Emphasis on individual variability-anthropometry, injury history, motor learning preferences-and on external constraints such as equipment and playing conditions will help tailor interventions that are both effective and sustainable. Equally important are ethical and pragmatic considerations: balancing performance enhancement with injury risk management, data privacy, and accessibility of technological resources.

Future research should expand on dose-response relationships for biomechanical training, validate predictive models across skill levels, and explore real‑time feedback systems that are robust in ecologically valid environments. Methodological transparency and standardized reporting will facilitate meta‑analytic synthesis and the progressive refinement of best practices.

Ultimately, optimizing golf swing biomechanics is an iterative, evidence‑based endeavor: to “optimize” is to make as effective, perfect, or useful as possible, and achieving that goal demands rigorous analysis, individualized application, and continual reassessment to translate biomechanical insight into measurable performance gains.