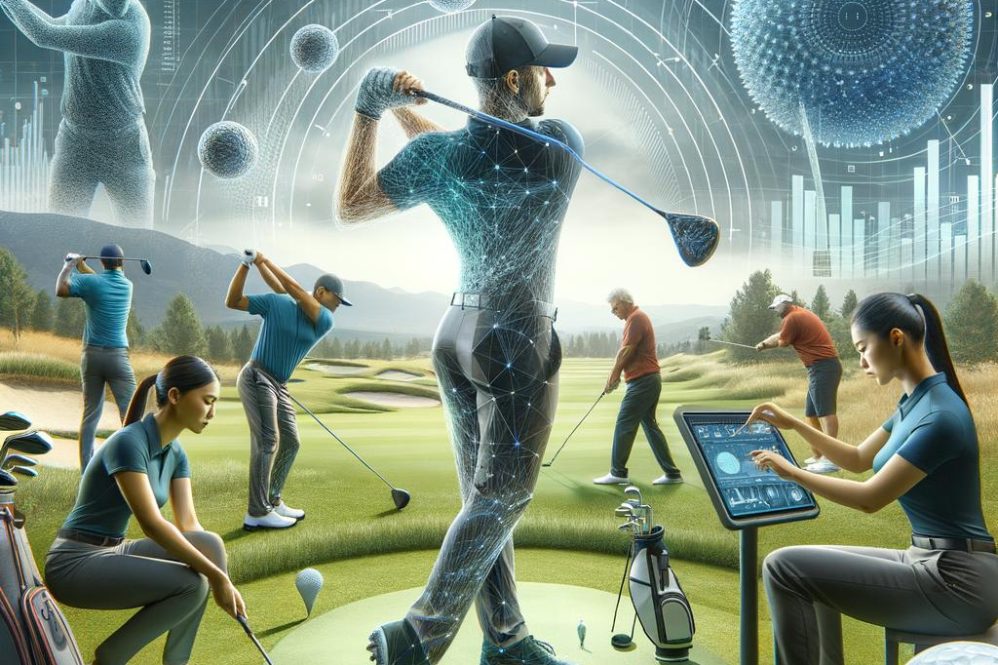

The development of reliable, repeatable golf technique remains a central objective for coaches, sport scientists, and players across all competitive levels. Despite widespread use of drill-based practice in coaching environments, there is considerable heterogeneity in how drills are designed, progressed, and evaluated, and a persistent gap between short-term technical gains on the practice tee and durable improvements in on-course performance. To address these challenges, this article adopts an evidence-based framework to evaluate how intentionally designed practice drills influence motor execution, intra- and inter-session consistency, and transfer of skill to competitive play.

For the purposes of this review, the term “structured” is used in its conventional sense: organized according to a specific plan or systematic format, with clear rules, objectives, and progression criteria (cf. Merriam-Webster; Definitions.net). Structured drills therefore contrast with ad hoc or unguided practice by embedding constraints,feedback schedules,and variability parameters that are deliberately chosen to scaffold learning. Treating drill design as an intervention allows for systematic comparison across studies and clearer mapping between practice components (e.g.,variability,contextual interference,feedback frequency) and observed outcomes.

Drawing on empirical motor-learning research,biomechanical analyses,and applied coaching studies,this article synthesizes current evidence on which drill characteristics most consistently promote technical refinement,movement stability,and transfer to on-course performance. Particular attention is paid to experimental work that manipulates practice structure (blocked vs. random practice,constant vs. variable practice), feedback modalities (augmented, delayed, summary), and task constraints (target complexity, environmental variability), as well as biomechanical investigations that link kinematic and kinetic markers to repeatable ball-flight outcomes.the objective is twofold: first,to provide an integrative,evidence-based account of how structured drill design affects golf skill acquisition; and second,to translate that evidence into practical,testable recommendations for coaches and practitioners. By bridging theoretical principles from motor control with applied findings from golf-specific research, the article aims to clarify which elements of structure are most likely to yield durable improvements in technique, consistency, and competitive performance.

Theoretical Foundations of Structured Drill Design in Golf

Theoretical constructs provide the conceptual scaffolding for designing drills that systematically shape golf behaviour rather then relying on intuition or tradition. In this context, the term denotes frameworks and hypotheses about how motor skills are acquired, stabilized, and transferred to performance environments – emphasizing explanatory power over immediate practicality. Anchoring drill design in theory enables precise manipulation of practice variables, principled prediction of transfer effects, and cumulative refinement across iterative testing cycles.

Contemporary motor-learning scholarship informs the selection and sequencing of exercises. Models such as Schema Theory and the Fitts-Posner stages highlight how generalized motor programs and stage-appropriate practice support acquisition, while Ecological Dynamics and the Constraints-led Approach foreground perception-action coupling, affordances, and task constraints as drivers of functional adaptation. Each framework yields distinct prescriptions for variability, feedback, and representativeness that should be reconciled when constructing an evidence-based drill progression.

Design principles derived from those models translate into operational rules for drills that facilitate both skill stability and adaptability. Core principles include:

- Specificity – align drills with the perceptual and mechanical demands of on-course tasks.

- Representative Variability – introduce controlled variability that preserves task-relevant details.

- Progressive Constraint Manipulation – modify environmental, task, or performer constraints to elicit desired adaptations.

- Feedback Scheduling – balance augmented and intrinsic feedback to optimize error-based learning.

- Deliberate Structure – sequence difficulty and complexity to match learner stage and goals.

| Theoretical Lens | Drill Design Feature | Anticipated Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| Ecological Dynamics | context-rich, variable targets | improved adaptability on-course |

| Schema Theory | Systematic parameter variability | Robust generalization across distances |

| Deliberate Practice | Focused repetition with defined metrics | Faster technical refinement |

Empirical rigor is essential when translating theory into practice: designs must emphasize ecological validity, use longitudinal measurement to capture learning curves, and report effect sizes to inform practical importance. Crucially, interventions must permit individualization because inter-player variability in perceptual strategies, physical capacities, and prior experience modulates response to identical drills. When theoretical assumptions are made explicit and operationalized, coaches and researchers can iteratively test, refine, and scale structured drills that elevate both technical proficiency and competitive performance.

Biomechanical Principles underpinning Effective Practice Movements

Contemporary practice design draws directly from the science of human movement: biomechanics provides the conceptual and quantitative framework for interpreting how joint rotations, segmental velocities, and external forces produce repeatable ball-flight outcomes. Emphasizing both **kinematics** (positions, velocities, accelerations) and **kinetics** (forces, moments, ground reaction forces), effective drills are informed by measurable movement variables rather than solely by subjective feel.This orientation encourages practitioners to define target metrics-such as clubhead speed, pelvis rotation, and shoulder turn-so that practice movements can be objectively assessed and iteratively refined.

One of the most robust principles applied to swing training is **proximal-to-distal sequencing**, whereby energy is transferred from larger, central segments (pelvis, trunk) to distal segments (forearms, club). Proper temporal sequencing optimizes angular momentum and minimizes compensatory torques that reduce efficiency. Drills that isolate timing (e.g., pause-and-release patterns, slow-motion sequencing) explicitly target this temporal coordination, enabling golfers to internalize the ideal intersegmental timing that underpins both power and accuracy.

Stability and force application are co-dependent components of effective practice movements.Maintaining a controlled centre of mass trajectory while generating appropriate ground reaction forces allows golfers to produce reliable impact conditions across variable contexts. Key biomechanical targets for drills include:

- Force direction-orienting push-off and lead-leg bracing to support rotational delivery;

- Base of support-managing stance width and foot pressure to balance mobility and control;

- Center-of-mass transfer-coaching weight shift patterns that preserve swing arc geometry.

Addressing these elements in practice reduces undesirable sway, inconsistent low-point control, and energy leaks that degrade on-course performance.

Motor learning principles drawn from biomechanics emphasize the value of structured variability and task-relevant feedback. Empirical studies indicate that varied practice conditions and augmented feedback (e.g.,immediate kinematic feedback,video,force-plate metrics) accelerate skill retention and transfer to competition settings. Consequently, effective drills are designed with graduated constraint manipulations-altering club length, stance, and tempo-to promote adaptable movement solutions rather than rigid repetition of a single motor pattern.

| Biomechanical Principle | Measurable Variable | Example Drill Focus |

|---|---|---|

| sequencing | Pelvis→Trunk phase lag (ms) | Slow-to-fast segmental rollouts |

| Force Production | Peak vertical/horizontal GRF (N) | single-leg braced rotations |

| Stability | COM excursion (cm) | Foot-pressure balance drills |

Integrating these measurable targets into a periodized practice plan enables evidence-based progression: quantify baseline mechanics, implement targeted drills, then reassess to confirm transfer toward improved consistency and course-level outcomes.

Motor learning Mechanisms and Transfer from Range to Course

Contemporary research on skilled movement identifies motor learning as a process of neural reorganization driven by goal-directed practice, error correction, and consolidation. Core mechanisms include sensory prediction error updating, reinforcement of successful action states, and use-dependent plasticity that refines motor synergies. These mechanisms operate across multiple timescales-rapid performance gains within sessions, offline consolidation between sessions, and long-term retention-each of which must be considered when structuring range practice intended to transfer to on-course performance.

Successful transfer from practice to competition depends on the similarity of critical task constraints: sensory information, movement dynamics, and decision-making demands. To maximize generalization, practitioners should design drills that vary context while preserving essential informational invariants. Key practical principles include:

- contextual interference: interleave different shots to promote adaptable motor plans.

- Perceptual coupling: integrate visual and situational cues (targets, wind, lies) during practice.

- Task variability: vary distances, clubs, and stance to broaden the repertoire of movement solutions.

Feedback modality and timing modulate which motor learning mechanisms are engaged: immediate, augmented feedback accelerates error-based learning but can reduce self-generated error detection; delayed or summary feedback promotes deeper processing and retention.Implicit learning strategies (analog cues, outcome-focused practice) often produce more robust transfer under pressure than explicit, rule-heavy instruction. Analogously to how an electric motor converts electrical input into mechanical output through predictable physical relationships, human motor control converts neural commands into coordinated club motion; the quality of that conversion depends on practiced mappings between intended outcomes and sensory consequences.

| Practice Element | Range Feature | Course Analog |

|---|---|---|

| Shot Variety | Repetitive targets | Undulating lies, wind |

| Decision Demand | Preset club selection | Risk-reward choices |

| Feedback Type | Immediate coach input | Self-assessed outcomes |

To promote measurable transfer, structure practice in progressive phases: establish accurate perceptual mapping (outcome-focused reps), introduce variability and contextual interference (randomized distances, constrained misses), and finalize with simulated course conditions (time pressure, on-course rehearsal).Employ objective monitoring (shot dispersion, launch data) and behavioral criteria (consistent decision rules) to determine progression. Emphasize **representative design**, incremental challenge, and feedback schedules that favor retention over transient performance gains to ensure range proficiency translates reliably to the course.

Empirical Evidence on Drill Frequency, Intensity, and Progression

Contemporary motor-learning research consistently favors spaced, short-duration practice over long, massed sessions for durable skill acquisition. Empirical work across sports and motor tasks indicates that **distributed practice** promotes retention and reduces performance decrements associated with fatigue, while massed practice can produce larger immediate gains that decay rapidly. For golf, this implies multiple brief drill blocks per week (e.g., 10-20 minutes focused on a skill) rather than infrequent, multi-hour “marathon” sessions if the objective is long-term improvement in technique and on-course transfer.

Intensity should be defined as the combination of cognitive focus, physical effort, and task difficulty rather than mere volume. Studies of deliberate practice show that **high-quality repetitions with clear intent and corrective feedback** deliver disproportionately greater learning than unguided quantity. Empirical findings recommend limiting high-intensity drill segments to volumes that avoid neuromuscular and attentional fatigue; beyond that threshold, additional repetitions yield diminishing returns or reinforce error patterns.

Progression schemes grounded in evidence adopt a staged increase in task complexity and variability. Early phases favor constrained or simplified tasks to establish movement coordination, then gradually introduce variability, decision-making, and environmental constraints to enhance adaptability. Frameworks such as the Challenge Point and scaffolding approaches-supported by experimental work in motor control-advocate optimizing difficulty so that practice remains challenging but achievable, thereby maximizing information for error-based learning and neuroplastic adaptation.

Integrative practice programs that align frequency, intensity, and progression with established learning principles tend to produce the best transfer to performance. Key empirically supported strategies include:

- Spacing: Short, repeated practice bouts spaced across days for retention.

- deliberate focus: Defined objectives and immediate, task-relevant feedback.

- Contextual interference: Interleaving different shot types to improve transfer.

- Gradual complexity: Move from stable drills to variable,decision-rich scenarios.

Ongoing measurement is essential to calibrate frequency and intensity. Coaches and players should track objective markers of improvement and fatigue, and adjust progression accordingly. A concise monitoring table supports evidence-based decision-making:

| metric | Practical target | Assessment Frequency |

|---|---|---|

| Shot dispersion (sd yards) | ≤ 5 yards (short game), ≤10 yards (long game) | Weekly |

| Carry consistency | ±10 yards from mean | Biweekly |

| Contact quality (center strikes %) | ≥ 80% | Session log |

Assessment Metrics for Technical Skill and Shot Consistency

Objective assessment underpins the evaluation of drill efficacy by translating observable swing behaviors into quantifiable outcomes. Emphasizing **validity** (does the metric measure the intended construct?) and **reliability** (is the measure stable and repeatable?) aligns golf performance appraisal with established psychometric principles. Instruments and protocols should be standardized-consistent sensor placement, sampling rates, and environmental controls-to minimize measurement error and allow meaningful comparisons across sessions and athletes.

Key domains for technical appraisal and repeatability include mechanical, kinematic, and outcome-based indicators. Typical measures used in evidence-based programs are:

- Club kinematics: clubhead speed, clubface angle, swing path

- Impact metrics: ball launch angle, spin rate, impact location on face

- Shot outcome: carry distance, total distance, lateral dispersion

- Temporal/neuromuscular: tempo ratios, ground reaction forces, sequencing

To operationalize these constructs, the following summary table maps primary metrics to recommended instruments and typical reliability considerations. Use this as a concise rubric when selecting measurement tools for drill assessment.

| metric | Measurement Method | Reliability Tip |

|---|---|---|

| Clubhead speed | Doppler radar / launch monitor | Average over ≥5 swings |

| Clubface angle at impact | High-speed camera / motion capture | Calibrate camera rig; use marker sets |

| Ball dispersion | Launch monitor / range mapping | Report SD and 95% ellipse |

| Impact location | Impact tape / face sensor | Consistent ball placement / mat |

Evaluating shot consistency requires statistical metrics that reveal both central tendency and variability. Report **mean** and **median** for central performance, and variability using **standard deviation (SD)**, **coefficient of variation (CV)**, and **95% dispersion ellipses** for spatial outcomes. For longitudinal drill studies, present intra-class correlation coefficients (ICC) to quantify test-retest reliability, and compute minimal detectable change (MDC) or smallest worthwhile change (SWC) to determine whether observed improvements exceed measurement noise.

Translating assessment into practice demands pre-defined performance thresholds and iterative benchmarking.Establish a baseline phase (e.g., 20-30 swings) to quantify within-subject variability, then set **progressive benchmarks** tied to both absolute performance (e.g., ±2 m carry deviation) and relative improvement (e.g., 10% reduction in CV). Combine objective metrics with structured coach ratings to capture contextual technical changes; use feedback frequency and task difficulty as experimental manipulations to evaluate which drill parameters produce reliable, transferable gains.

Designing Individualized Drill Protocols Based on Player Profiles

Designing practice protocols begins with a principled translation of assessment data into targeted interventions. A robust player profile synthesizes objective measures (swing kinematics, launch-monitor dispersion, movement screening) with experiential data (practice history, competitive behavior). This synthesis permits the selection of drills that align with specific mechanisms of error and the player’s adaptive capacity, rather than relying on generic “one-size-fits-all” routines. Emphasizing **biomechanics**, **perceptual demands**, and **motor learning constraints** yields protocols that are theoretically grounded and practically actionable.

Core assessment domains that inform individualized drill selection include the following, each mapped to intervention priorities:

- Technical/kinematic: club path, face control, pelvis-shoulder sequencing – prioritize movement-specific corrective drills.

- Performance variability: shot dispersion,strike consistency – emphasize variability and error-reduction drills.

- Physical capacity: mobility, stability, power – incorporate pre-shot activation and strength-sparing adaptations.

- Cognitive/attentional: decision-making under pressure, working memory – integrate dual-task and situational simulations.

- Practice history & preferences: prior success with blocked vs. random practice, feedback sensitivity – tailor feedback schedule and task structure.

translating profile elements into concrete drill families entails matching the task constraint to the desired learning mechanism. For players with mechanical faults and low variability, use **error-amplification** or constrained drills that isolate the targeted DOF; for players with high variability but intact mechanics, prioritize **stabilization and consistency** drills with reduced degrees of freedom. Recommended drill families include:

- Mechanics isolation drills (mirror work, slow-motion segments).

- Perceptual-motor drills (target discrimination, time-pressure simulations).

- Variability training (randomized targets, variable clubs, altered lie).

Each drill should have a clear hypothesis (what will change and why) and measurable outcome criteria.

Progression,dosing,and feedback must be prescribed with the same rigor as the drill selection. Establish session microcycles with explicit sets,repetitions,and inter-trial intervals that reflect the learning objective (e.g., massed practice for motor patterning vs. distributed practice for retention).The table below offers a concise mapping of illustrative profiles to sample drills and session dosing parameters for pragmatic implementation.

| player Profile | Sample Drill | Session Dose |

|---|---|---|

| Low dispersion, mechanical flaw | Slow-swing segmenting + impact tape | 4 sets × 8 reps, low augmented feedback |

| High dispersion, sound mechanics | Variable target ladder (randomized distances) | 6 sets × 6 reps, intermittent feedback |

| Pressure-averse performer | Simulated pressure holes (bets, crowd noise) | 3 blocks × 10 reps, increasing situational load |

Monitoring and iterative refinement are essential to maintain ecological validity and efficacy. Use a combination of objective metrics (shot-to-shot dispersion, carry distance CV, impact location heatmaps) and subjective indicators (perceived exertion, attentional focus) to evaluate progress against pre-defined thresholds. Decision rules might include: reduce external feedback if retention exceeds 80% at two-week retest,or regress task complexity when dispersion deteriorates by >15%. embedding these **data-driven decision rules** in the practice plan ensures drills remain individualized, measurable, and responsive to the player’s trajectory.

Integrating Cognitive and Perceptual Training into Drill Frameworks

Contemporary models of skill acquisition emphasize that motor proficiency is inseparable from higher-order mental processes; cognition encompasses perception, attention, memory and decision-making and functions as the information-processing substrate for action. Integrating these processes into practice requires explicit targeting of perceptual cues and cognitive operations during drill design so that learning addresses both the biomechanical pattern and the underlying mental representations that guide shot selection and execution. Such an integrated approach encourages the formation of robust, context-sensitive skills rather than isolated movement patterns.

Design principles rooted in motor learning and cognitive psychology should govern drill construction. Prioritize **specificity** (match perceptual demands of competition), **graded complexity** (progressively increase cognitive load), **variability** (promote transfer), and **task-relevant feedback** (reduce dependency). Example cognitive targets include:

- Selective attention – focusing on task-relevant visual cues amid distractors;

- Working memory – retaining wind, club, and yardage information during pre-shot routines;

- Anticipation and pattern recognition – reading green breaks and approach-lie patterns;

- Decision-making under time pressure – optimizing club choice and risk assessment.

Practical drills combine perceptual manipulations with standard skill tasks to elicit desired cognitive processes. The following table offers concise examples mapping drill, primary cognitive target, and a simple measurable outcome; it can be used to structure practice blocks and assess progression.

| Drill | Cognitive Target | Outcome metric |

|---|---|---|

| Dual-task putting | Working memory + attention | % putts holed under distraction |

| Occlusion chipping | Visual prediction | Landing accuracy (cm) |

| Time-constrained tee shots | Decision-making | choice optimality score |

Evaluation should emphasize **objective measurement** and transfer: track response times, error rates, task completion under distraction, retention over delayed tests, and on-course transfer measures. Eye-tracking and verbal protocol analysis can elucidate perceptual strategies (where permitted), while short-term retention tests and simulated pressure trials estimate durability. Framing cognition as an information-processing system (perception → selection → memory → execution) helps to identify which processing stage a drill targets and to interpret performance changes mechanistically.

Implementation must be systematic: periodize cognitive load across mesocycles, integrate short high-load sessions within technical practice, and schedule dedicated cognitive-perceptual blocks twice weekly during skill acquisition phases. Recommended microstructure includes alternating high-variability days with consolidation days, employing progressive difficulty and withdrawing augmented feedback to foster independence. coaches should monitor subjective workload and adapt progression criteria so that cognitive challenge enhances, rather than overwhelms, motor learning.

Practical Implementation Guidelines and Evidence Based Recommendations

Adopt a structured, periodized practice plan that balances skill acquisition with retention and transfer.Empirical motor-learning studies support distributed practice over massed sessions for durable gains; thus schedule shorter, higher-frequency sessions (20-45 minutes, 3-5× per week) rather than long, infrequent blocks. Emphasize progressive overload of task difficulty: begin with constrained, low-variability drills to stabilize technique, then systematically introduce variability to promote generalization. key prescription: progress from 70-80% accuracy-focused repetitions to 50-60% variability-driven practice within a 4-6 week microcycle, adjusted for athlete skill level and fatigue.

Implement feedback policies consistent with evidence for optimal learning: use augmented feedback sparingly and with a faded frequency model to encourage intrinsic error detection. Integrate objective, external KPIs (e.g., dispersion radius, launch-angle consistency, clubhead speed SD) and combine them with qualitative biomechanical cues when necessary. Practical drill examples with escalating constraints include:

- Block basic – 30 slow, repeatable swings focusing solely on kinematic sequence;

- Variable-target – 3×5 shots to varying distances/targets to enhance adaptability;

- Pressure transfer – 9-hole simulated challenge with scoring to train decision-making under stress.

Apply real-time video or launch-monitor feedback during early stages, then restrict to summary feedback (every 8-12 trials) once movement patterns stabilize.

Quantify progress using simple, reproducible metrics and follow a data-driven adjustment rule. Recommended core metrics: mean dispersion (m), coefficient of variation (CV) for carry distance, and within-session trend slope for launch angle. Use a basic monitoring table to guide weekly decisions and to communicate outcomes to the learner and coach:

| Metric | baseline | Target (4 wks) |

|---|---|---|

| Mean dispersion (m) | 12 | 8-9 |

| Carry CV (%) | 7.5 | ≤5 |

| Launch-angle SD (deg) | 1.8 | ≤1.2 |

Maximize on-course transfer by embedding contextual interference and representative task constraints. Randomized practice schedules and mixed-task blocks produce superior retention and transfer compared with purely blocked practice; however, use a staged approach so early technical consolidation is not compromised. Include simulation of environmental factors (wind, lies, pressure scoring) and a concise pre-shot routine to standardize psychological state. For advanced players, alternate high-variability sessions with targeted, biomechanically focused sessions (e.g., tempo/sequence drills) to maintain movement efficiency while expanding adaptability.

Prioritize individualization, safety, and longitudinal monitoring when integrating structured drills into a training plan. Adjust volume and intensity according to fatigue, chronic workload ratios, and physical screening results; combine drill work with strength and mobility protocols that address swing-specific constraints (thoracic rotation, hip stability). Use conservative progression rules (≤10-15% weekly increase in task demand) and schedule deload weeks after 3-4 hard microcycles. document drills,feedback methods,and objective outcomes to facilitate iterative refinement and to align practice with empirically supported principles.

Q&A

Q: What do you mean by “structured golf drills” in the context of evidence‑based skill development?

A: In this context, “structured” denotes a deliberately organized, systematic sequence of practice activities with predefined objectives, progressions, constraints, and measurement criteria (cf. Cambridge Dictionary; Merriam‑webster). structured golf drills are therefore practice tasks designed to elicit specific technical,perceptual or decision‑making adaptations,guided by principles from motor learning,biomechanics and sport science.

Q: What is the theoretical basis for using structured drills to improve golf performance?

A: Structured drills draw on motor learning theories (e.g., deliberate practice, variable practice, contextual interference), control and coordination principles from biomechanics, and evidence about feedback, attentional focus, and task specificity. Together these frameworks predict that well‑designed, progressive, measurable drill programs should accelerate acquisition, increase consistency, and improve transfer to competitive tasks when practice mimics task demands and provides appropriate variability and feedback.

Q: What types of empirical evidence support structured drills in golf?

A: Evidence comes from (1) intervention studies comparing different practice schedules or feedback conditions, (2) longitudinal training studies measuring performance change over weeks-months, (3) biomechanical analyses documenting changes in kinematics/kinetics associated with specific drills, and (4) transfer studies testing on‑course outcomes (e.g., proximity to hole, strokes gained). The highest quality evidence uses controlled,randomized designs with retention and transfer tests; however,much golf research is observational or uses small samples.

Q: Which motor‑learning principles should guide the design of structured golf drills?

A: Key principles are:

– goal specificity and measurable objectives (what performance metric will change).

– Progressive overload and staged complexity (skill progressions).

– Variable practice to support adaptability and transfer.- Contextual interference (mixing tasks) to favor long‑term retention and transfer.

– Appropriate feedback schedule (reduced/summary feedback to avoid dependency).

– External attentional focus cues to improve performance and learning.

– distributed practice and deliberate repetition of high‑value reps.

Q: How do biomechanical findings inform drill selection and progression?

A: Biomechanical analyses identify the kinematic and kinetic targets linked to desired outcomes (e.g., consistent clubface orientation at impact, effective energy transfer through the kinetic chain). Drills can be chosen to emphasize these variables (e.g., weight‑shift drills to enhance ground reaction impulse, tempo drills to stabilize sequencing). Objective measurement (motion capture, launch monitors) can confirm that drills change the targeted mechanical variables before assuming performance transfer.

Q: Do structured drills improve technical skill (swing mechanics, contact) empirically?

A: The literature shows that targeted, systematic practice can produce measurable improvements in swing kinematics and impact conditions (clubhead speed, smash factor, clubface angle) when drills are aligned with the biomechanical target and accompanied by appropriate feedback. Effect sizes depend on participant skill level, drill specificity, practice dose, and measurement sensitivity.Q: What evidence links structured drills to improved consistency?

A: Studies that measure variability across repeated trials demonstrate that structured drills-particularly those emphasizing rhythm, alignment, and impact cues-can reduce within‑session dispersion (e.g., tighter shot patterns, reduced clubface angle variance). Variable practice and constraint manipulation can also reduce sensitivity to perturbations, improving consistency under differing conditions.

Q: Is there reliable evidence that structured drills translate to better on‑course performance?

A: Transfer to on‑course performance is more challenging to demonstrate and is less well documented. Some intervention studies report improvements in proximate metrics (proximity to hole,greens in regulation,strokes gained in practice scenarios),but broad generalization to tournament scoring depends on ecological validity of the drills,pressure conditions,and course management training. More randomized controlled trials with long‑term follow‑up and on‑course transfer tests are needed.

Q: how should practitioners measure the effectiveness of a drill program?

A: use a combination of:

– Objective technical metrics (launch monitor data, club/segment kinematics).

– Performance metrics (dispersion, proximity to hole, GIR, short game up‑and‑down rates).

– Consistency measures (standard deviation across trials).

– Retention and transfer tests (delayed retention; performance under simulated pressure or on course).

Pre‑define success criteria and collect baseline, post‑intervention, and retention data.

Q: How can drills be structured for different skill levels (novice vs expert)?

A: novices benefit from high‑structure,simplified tasks with clear external focus cues and frequent feedback,progressing from blocked to more variable practice. Experts require drills that target fine‑tuning, variability and decision making under pressure; practice should emphasize representative tasks, mixed contexts, and lower feedback frequency to preserve autonomy and adaptability.

Q: Can you give examples of evidence‑based structured drills and their rationale?

A: Examples:

– Impact‑target drill: Place a narrow target at a specific yardage and require consistent dispersion; rationale: external focus and target specificity drive better impact outcomes and transfer.

– Tempo metronome drill: use a metronome to standardize backswing‑downswing ratio; rationale: stabilizes sequencing and timing,reducing kinematic variability.

– Constraint‑led variable lies drill: Practice shots from varied tee mats/rough/sidehill in randomized order; rationale: increases adaptability and contextual interference for transfer.

– short‑game proximity ladder: Gradually reduce allowed proximity to hole in progressive stages; rationale: deliberate repetitions with increasing task difficulty and performance feedback.

Q: What are the common limitations and methodological gaps in current research?

A: Limitations include small sample sizes, heterogeneous participant skill levels, short intervention durations, inconsistent outcome measures, lack of randomized controls, and insufficient on‑course transfer testing. Few studies examine retention beyond weeks or account for individual differences in learning rates.

Q: What practical recommendations emerge for coaches and athletes?

A: Recommendations:

– Define specific,measurable learning objectives before selecting drills.

– Use biomechanical and performance data to select drills that target known deficits.

– Balance blocked and variable practice; move from high structure to representative variability.

– Reduce frequency of corrective feedback over time; emphasize external focus cues.

– Monitor objective metrics and conduct retention/transfer assessments.

– Individualize dose and progression, and incorporate pressure simulation for transfer.

Q: What are key directions for future research?

A: Future research should prioritize randomized controlled trials with larger samples,standardized outcome sets (technical,consistency,on‑course),long‑term retention and transfer tests,exploration of individual differences (e.g., motor abilities, cognitive styles), and integration of biomechanical and neurophysiological measures to elucidate mechanisms of learning in golf.

Q: Summary: What is the bottom line about structured golf drills and evidence‑based skill development?

A: structured golf drills, when designed and implemented according to motor‑learning and biomechanical principles and validated with objective measurement, have demonstrated capacity to improve technical skills and consistency. transfer to on‑course performance is plausible but less consistently documented; achieving transfer requires representative practice, appropriate variability, and systematic assessment. Continued rigorous research and careful practitioner monitoring will strengthen the evidence base and optimize drill design.

The Way Forward

the evidence reviewed indicates that carefully structured practice drills-characterized by clear objectives, measurable progressions, principled variability, and targeted feedback-can meaningfully enhance technical proficiency and shot-to-shot consistency in golf. Biomechanical analyses clarify how specific movement patterns and kinetic sequences underpin successful stroke mechanics,while empirical studies of practice structure and contextual interference provide guidance on how to organize repetitions to promote learning and transfer. Though, effect sizes and transfer to competitive on‑course performance are moderated by task specificity, learner characteristics, and the ecological fidelity of practice environments, and the literature exhibits methodological heterogeneity that limits broad generalization.

For practitioners, the implication is to adopt an evidence‑informed framework when designing drills: define explicit performance goals, sequence progressions from constrained to variable practice, integrate objective measurement (video, launch‑monitor and wearable data), and embed decision‑making elements that approximate on‑course demands. Coaches should individualize drills to the athlete’s technical profile and competitive context, monitor retention as well as immediate performance gains, and use feedback modalities that foster self‑regulation and motor planning rather than dependency.

Future work should prioritize longitudinal, ecologically valid designs that evaluate retention and competitive transfer, investigate dose-response relationships for different drill types, and leverage advancing measurement technologies to link biomechanical markers with performance outcomes.Bridging the gap between laboratory insights and field application remains essential: by aligning coaching practice with robust, replicable evidence, the golf community can more effectively translate mechanistic understanding into durable skill development and improved competitive performance.

structured Golf Drills: Evidence-Based Skill Development

Why Structured Golf Drills Matter

Golfers who practice with purpose get better faster. Structured golf drills turn time on the range into measurable skill development rather than random swings. By combining golf-specific drills with evidence-based motor learning principles-like intentional practice, variability of practice, and effective feedback-you can improve consistency, lower scores, and gain confidence on the course.

Core Evidence-Based Principles for Skill Development

- deliberate practice: Focused, goal-oriented reps with immediate feedback are more effective than volume alone.

- Specificity: Practice should mimic on-course situations (short game from tight lies, contested putts, partial swings under pressure).

- Variability of practice: Mixing distances,lies,targets,and clubs builds adaptability and retention.

- Distribution and spacing: Shorter, frequent sessions beat occasional marathon sessions for long-term learning.

- External focus: Cueing attention to the target or ball flight (rather than body parts) consistently improves performance.

- Progressive overload and scaling: Gradually increasing difficulty (smaller targets, pressure, or randomization) drives adaptation.

- Feedback: Use a mix of intrinsic feel, video analysis, launch monitor data, and coach input-but limit overreliance on instant metrics to avoid breaking rythm.

Key Skill Areas & How to Structure Drills

Full Swing: Accuracy, Speed & tempo

Goal: Develop a repeatable swing that produces consistent ball flight, distance control, and accuracy.

- Warm-up: 10-15 slow wedges → mid-irons → driver using half to full swings.

- Tempo drill (4-2-1): Count backswing 4, transition 2, and through-swing 1 to stabilize tempo.

- Alignment + target focus: Place alignment rods and pick a narrow target; focus on an external target to improve accuracy.

- Random distance ladder: Hit 7-9 shots at randomized yardage with irons to promote carry control and dynamic decision-making.

Short Game: Chipping and Pitching

Goal: Reduce up-and-down failures and save strokes inside 100 yards.

- Landing-zone reps: Pick a spot on the green to land the ball and hit 10-20 shots from varied lies to that landing zone.

- One-handed chipping: Improve feel and control by alternating left- and right-hand-only chips (8-10 each).

- Bump-and-run vs. lob decision drill: from same yardage, practice both shots to understand roll vs. carry trade-offs.

Putting: Speed & Line

Goal: Improve three-putt avoidance and make more mid-range putts.

- Gate drill for stroke path: Use tees to create a gate the putter must pass through for cleaner contact.

- 3-2-1 speed drill: Putts from 20, 15, and 10 feet-set a goal for made + near misses to build speed control.

- Pressure sets: make 5 of 7 from 8-12 feet; if you miss, reset to the start to simulate competitive pressure.

Structured Drill Library (Step-by-Step)

1. Target-Ladder Iron Drill (accuracy + Distance Control)

- set targets at 50%, 75%, and 100% of your iron distance (e.g., 50, 75, 100 yards).

- Hit 5 shots at each target in sequence, then rotate clubs and repeat for 3 rounds.

- Use a launch monitor or mark landing spots to track dispersion and carry.

2. 60-Second Tempo Series (Tempo & Rhythm)

- Using a metronome (or count), perform 60 seconds of half swings at 60% speed focusing on rhythm.

- Promptly hit 8 full shots with the same tempo. Record feel and ball flight.

3. Inside-100 Progressive Challenge (Short Game)

- From 60, 40, and 20 yards, attempt 3 chips/pitches to the same landing zone.

- If 2 of 3 are successful, move to the next closer distance; miss twice and repeat until you pass.

4. Pressure Putting Ladder (Putting)

- Start at 6 feet: make 1 putt. Move to 8, 10, 12, 15, and 20 feet.

- If you miss any, step back two distances and repeat. Goal: climb the ladder without failing twice in a row.

Sample Practice Plans (Structured Routines)

Below are reproducible practice session templates. Each session ties drills back to measurable goals.

| session | Duration | Focus | Drills |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rapid Tune | 30 min | Putting + Wedges | 3-2-1 Speed Drill + 20 wedge landings |

| Precision Session | 60 min | irons + Short Game | Target Ladder + Inside-100 Challenge |

| Range & Course Control | 90 min | Full Swing + Simulation | Tempo Series + random Distance Ladder + 9-hole simulation |

Weekly Macrocycle Example

- Monday: Recovery + putting (30-45 min)

- Tuesday: Full Swing (60-90 min, focus on speed & accuracy)

- Wednesday: Short Game intensity (45-60 min)

- Thursday: Light technique work + mobility (30-45 min)

- Friday: Simulation round or pressure practice (90-120 min)

- saturday: Tournament/competitive play or long format practice

- Sunday: Rest or active recovery

Tracking Progress: metrics That Matter

To evaluate structured drill effectiveness, track objective and subjective measures:

- Score-based: Putts per round, scrambling %, GIR (greens in regulation).

- range-based: Carry distance consistency,dispersion (left/right),club-specific carry averages.

- Short game: Up-and-down percentage from 30-60 yards, proximity to hole from pitch/chip.

- Putting: Make rate from 6-20 feet, average distance left from putts that miss.

- Subjective: Confidence, tempo rating (1-10), perceived pressure performance.

Applying Motor Learning: Practice Design Tips

- Use mixed practice over blocked practice for better retention-e.g., rotate irons instead of hitting 50 of the same shot.

- Add variability: change tees, lies, wind, and targets to simulate course conditions.

- implement contextual interference: alternate between full shots and short-game shots to accelerate decision-making.

- Limit technology overload: use launch monitors for baseline data but practice mostly with on-course feel cues.

- Introduce pressure: use consequences (bets, small rewards, or partner challenges) to simulate tournament stress.

common Pitfalls & How to Avoid Them

- Mindless reps: always have an outcome-based target (landing zone, made putts, dispersion pattern).

- Too many cues: Use one or two simple cues (e.g., “turn and release” or “focus on landing spot”) to avoid overthinking.

- Over-reliance on metrics: Numbers inform but don’t replace feel and decision-making-balance both.

- no progression: Increase difficulty gradually; if a drill becomes too easy,add pressure or reduce target size.

Case Study: From Practice to Lower Scores (Illustrative)

Player A was averaging 38 putts and had inconsistent approach distances. A 12-week structured plan focused on:

- Two 30-minute putting sessions per week using the 3-2-1 and pressure ladder drills

- One focused short-game session (landing-zone reps,one-handed chips)

- One range session with randomized iron distances and tempo work

Outcomes after 12 weeks (tracked): putts per round reduced to 31,up-and-down % improved by 12 points,and approach dispersion tightened by 20%. The player reported greater course confidence and lower score variability. This demonstrates how disciplined, evidence-based practice translates to on-course results.

Practical Tips for Coaches and Players

- Plan practice with a weekly goal and three measurable outcomes (e.g., reduce three-putts, improve 8-12 foot make rate, tighten 7-iron dispersion).

- Warm up with intention: mobility → short game → swing.Never start a session with full-power driver swings cold.

- Keep practice logs: date, drills, metrics, perceived difficulty, notes-review weekly.

- Use short, frequent sessions (20-45 min) to maintain freshness and retention rather than long, infrequent blocks.

- Rotate focus areas across weeks using a microcycle (short game emphasis week, tempo week, simulation week).

WordPress Styling Snippet (Optional)

/* Add to the theme's custom CSS */

.wp-table {

width: 100%;

border-collapse: collapse;

margin-bottom: 1.5rem;

}

.wp-table th, .wp-table td {

border: 1px solid #ddd;

padding: 8px;

}

.wp-table thead th {

background: #f7f7f7;

text-align: left;

}

Next Steps: Build Your Own Structured Drill plan

1) Pick one measurable weakness (putting, approach dispersion, short-game percentage). 2) Choose 2-3 drills from above that address that area. 3) Set frequency (e.g., 3x/week) and a 4-12 week goal. 4) Track sessions and results; adjust difficulty every 7-14 days.

Using structured golf drills grounded in evidence-based practice principles will make your practice time efficient and translate into better on-course performance. focus, variability, measurable goals, and gradual progression are the key ingredients to lasting improvement.