The golf swing is a highly intricate motor task that must reconcile two frequently enough competing goals: producing maximal clubhead velocity with precise ball placement, while limiting the cumulative loads that increase the likelihood of musculoskeletal injury. From casual weekend players to touring professionals, marginal improvements in performance and reductions in injury rates increasingly depend on precise, mechanistic descriptions of movement. Biomechanics – the interdisciplinary field that applies mechanical principles to biological form and function – supplies both the conceptual language and the measurement tools needed to objectively describe movement patterns, the forces acting on tissues, and the neuromuscular strategies that generate them.

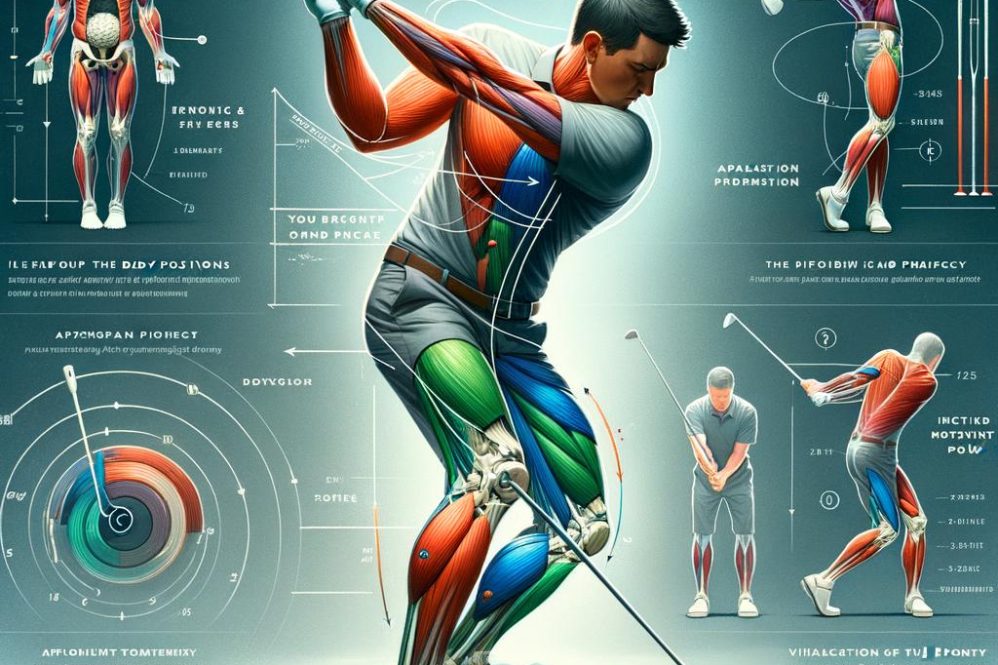

This review brings together contemporary biomechanical insights into the golf swing across three interrelated perspectives. Kinematics capture the timing and geometry of body segments (for example, pelvis‑thorax dissociation, shoulder plane orientation, and wrist hinge) and explain the proximal‑to‑distal sequencing typical of skilled swings. Kinetics measure forces and moments (including ground reaction forces, intersegmental torques, and club-hand interactions) to reveal the mechanical drivers of ball speed and variability in shot outcome. Neuromuscular analysis – via surface electromyography, muscle‑timing studies, and musculoskeletal simulation – clarifies how patterns of activation and stretch‑shortening mechanisms shape energy transfer, postural stability, and tissue loading.

Technological advances (high‑speed optical capture, force plate systems, wearable inertial sensors, portable EMG, and forward/inverse dynamics modeling) have expanded the resolution and ecological validity of available data, though variability in study methods and reported metrics still complicates cross-study synthesis. Core biomechanical themes that persist across the literature include coordinated sequencing of angular velocities, an optimal pelvis‑thorax separation (X‑factor), strategic use of ground reaction forces, and control of excessive lumbar shear and torsional demands – each with direct implications for performance and for common golf injuries (low back, elbow, shoulder, wrist).

This article therefore aims to (1) integrate kinematic, kinetic, and neuromuscular evidence into a unified framework for swing evaluation; (2) highlight biomechanical indicators that distinguish skill levels and flag injurious loading patterns; and (3) convert these findings into practical, evidence‑informed guidance for coaching, conditioning, and rehabilitation. By linking mechanistic understanding to applied practice, the goal is to support technique adjustments that raise performance potential while reducing musculoskeletal harm.

Kinematic Sequencing and Intersegmental Coordination in the Golf Swing

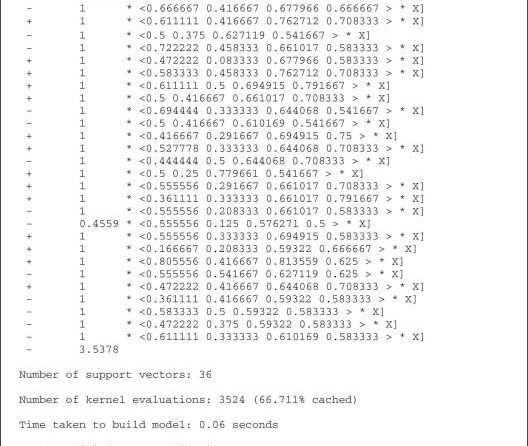

effective swings depend on a predictable proximal‑to‑distal chain of angular motion: rotation begins in the lower trunk, the pelvis initiates the lead over the thorax, the shoulders follow, and the arm‑and‑club system completes the energy transfer. this ordered cascade – frequently enough referred to as the kinematic sequence – optimizes clubhead speed while lowering internal muscular work. Mechanically, it depends on staggered peaks in segmental angular velocity so that each proximal segment reaches its maximum before the next distal link, enabling constructive transfer of angular momentum rather than destructive interference.

Researchers quantify this cascade using discrete markers and continuous waveform methods. Typical measures include peak angular velocity (PAV) for pelvis, thorax and arms; timing of PAV relative to impact; the X‑factor (axial separation between thorax and pelvis); and intersegmental phase relationships. Useful indicators for both science and coaching are:

- sequence of pavs – generally pelvis → thorax → upper trunk → arms → club.

- Temporal offsets – the millisecond gaps between successive peaks that indicate efficient transfer.

- Relative amplitudes – ratios of PAV magnitudes that show how power is distributed among segments.

- Consistency across trials – variability measures that reflect motor control stability.

Comparisons across ability levels show that skilled golfers produce repeatable timing patterns with lower trial‑to‑trial variability and favorable magnitude ratios; beginners typically display compressed or disordered timing that reduces transfer efficiency and forces greater compensatory effort from proximal musculature. From a motor control outlook, robust coordination emerges from feedforward activation timing honed by experience and targeted practice. Thus, evaluations should combine absolute timing metrics (e.g., milliseconds to PAV) with variability indices to separate stable expertise from ephemeral improvements.

Interventions aimed at both technique and tissue tolerance are complementary: enhanced hip and thoracic mobility supports healthier separation angles, while eccentric capacity and rapid force production in trunk rotators and shoulder stabilizers reduce injurious loading when sequencing is imperfect. For field monitoring and coaching, wearable IMUs or high‑frame‑rate video can quantify timing targets; drills that emphasize delaying the arm release or initiating earlier pelvic rotation are commonly used to retrain the timing hierarchy.The following table provides approximate relative timing benchmarks for reference.

| Segment | Typical order | Relative Timing (to impact) |

|---|---|---|

| Pelvis | 1 | ~120-80 ms before impact |

| Thorax | 2 | ~80-40 ms before impact |

| Arms/Club | 3 | ~40-0 ms before impact (club peak at or just prior to impact) |

Ground Reaction Forces and Joint Kinetics as Determinants of Power and Mechanical Load

The way a golfer interacts with the ground is central to how swing power is generated. Ground reaction forces (GRFs) provide the external impulses that are converted into joint moments via inverse dynamics; the vertical, medial‑lateral and anterior‑posterior components, together with shifts in the center of pressure, create net moments at the ankle, knee and hip. Force‑platform research indicates that not only the magnitude but the timing and vector of GRFs influence how efficiently energy ascends the kinematic chain. Well‑timed peak vertical force coincident with the start of hip rotation magnifies proximal joint moments and primes the trunk and shoulder for effective loading.

Typical swing sequencing relies on purposeful GRF modulation to support the proximal‑to‑distal cascade.Loading toward the trail foot during the backswing stores compressive energy, and a rapid transfer and impulse into the lead foot at transition converts that stored energy into rotational acceleration. This ground‑to‑body impulse elevates internal moments – notably at the hips and lumbar spine – that are then transmitted distally to accelerate the shoulders,elbow and wrist. Faster rates of force progress (RFD) under the feet align with higher clubhead speeds but also correspond with larger instantaneous joint kinetics.

| Phase | Peak Vertical GRF (×BW) | Representative Hip moment (Nm·m/kg) |

|---|---|---|

| backswing | 1.1 | 0.8 |

| Transition | 1.5 | 1.4 |

| Downswing | 2.0 | 2.1 |

| Impact | 2.4 | 2.6 |

These representative values illustrate how vertical GRF rises across the propulsive phases and how hip moments increase correspondingly; treat the numbers as conceptual benchmarks rather than strict norms for every golfer.

While higher joint kinetics can boost performance,they also raise mechanical stress and injury potential – especially at the lumbar spine and lead hip. The combination of elevated compressive loading, rapid trunk torsion, and eccentric braking demands on the lead knee creates complex, multiaxial stresses that can overload tissues. Practical mitigation tactics include:

- Eccentric strengthening of hip and thigh musculature to better absorb transition impulses;

- Trunk motor‑control drills to moderate rapid rotations and reduce shear;

- Foot‑ground mechanics coaching (stance width and plantar pressure distribution) to optimize force direction;

- Gradual exposure to high‑RFD exercises so connective tissues adapt safely.

Optimization requires a trade‑off: maximize useful horizontal and vertical GRF components to increase speed while keeping joint loads within safe bounds. Coaching cues that encourage directing force slightly lateral‑to‑medial under the lead foot and initiating hip rotation immediately after peak vertical impulse generally improve mechanical efficiency. Objective feedback – force plate traces synchronized with kinematics and joint moment estimates – enables individualized thresholds for safe power development. Ultimately,pairing neuromuscular conditioning,technique refinement and progressive loading offers the best chance to raise clubhead speed while limiting cumulative mechanical stress.

Muscle Activation Patterns and Neuromuscular Control across Swing Phases

Surface EMG studies show that high‑quality swings are defined more by well‑timed activation patterns than by maximal muscle recruitment alone. Skilled players commonly exhibit anticipatory pre‑activation of trunk rotators, gluteal muscles, and scapular stabilizers in the late setup and early backswing, creating a stable base for later energy transfer.This feedforward activity reduces the need for reflex corrections during rapid phases; quantitatively, shorter EMG onset latencies and lower trial‑to‑trial timing variability associate with improved shot consistency and reduced lumbar load.

Muscle recruitment tends to follow the same proximal→distal motor pattern: torso and hips start rotational momentum, then the upper trunk and lead arm engage, and wrist extensors fire near impact. Principal contributors include:

- Gluteus maximus / medius – hip drive and lateral stability

- Erector spinae / obliques – trunk rotation control and energy conduit

- Rotator cuff & scapular stabilizers – clubface and shoulder positioning

- Forearm/wrist extensors – fine velocity control and impact moderation

During transition and downswing, the neuromuscular emphasis is on precise timing and selective co‑contraction to balance mobility with segmental stiffness. Purposeful co‑activation of trunk and hip stabilizers helps maintain a lag between proximal and distal segments, enabling elastic energy storage and release via the stretch‑shortening cycle. Combined force‑plate and EMG research indicates that synchronized GRF production and tight muscle timing reduce energy losses and dampen shear forces that contribute to injury.

Practical training priorities derived from neuromuscular findings include:

| Target | Modality | Primary Benefit |

|---|---|---|

| Pre‑activation & timing | EMG biofeedback drills | Sharper onset precision |

| Proximal stability | Hip/trunk isometrics | Improved energy transfer |

| Eccentric control | Nordic/controlled decelerations | Lower injury risk |

from an injury‑prevention perspective, atypical neuromuscular signatures – delayed trunk activation, excessive ipsilateral co‑contraction, or inconsistent pre‑activation – predict higher lumbar shear and shoulder loads. Coaches and clinicians should thus apply objective monitoring (EMG, force plates, high‑speed kinematics) and deliver targeted rehabilitation: eccentric strengthening, proprioceptive tasks, and tempo‑controlled swing repetitions to recalibrate feedforward control. Simple on‑course checks include consistent pre‑shot muscle tone, maintained hip rotation before wrist release, and low swing‑to‑swing timing variability.

Trunk and Hip Mechanics in Energy Transfer and Low‑back Injury Risk

Transfer of energy from the lower limbs to the club relies heavily on coordinated trunk and hip mechanics: pelvic rotation, thoracic counter‑rotation and well‑timed activation of obliques and erector spinae produce the stored elastic energy that can be released into the upper torso. The magnitude of pelvis‑thorax separation (X‑factor) and the speed of its recoil influence how much elastic recoil is available and the peak angular velocity of the torso. Kinematic studies suggest that emphasizing hip rotational velocity while maintaining a controlled thoracic turn can increase clubhead speed without proportionally increasing lumbar rotation – provided intersegmental timing remains smooth and abrupt trunk collapse is avoided.

Kinetically, the lumbar spine is subjected to a complex mix of compression, shear and torsion during transition and downswing. Forces generated by the legs and hips can be managed safely by the spine if the hips have sufficient rotation and extension capacity. EMG work highlights coordinated activity of gluteus maximus, multifidus and obliques during fast swings; by contrast, hip mobility restrictions or timing errors shift rotational demands onto lumbar tissues, elevating peak shear and cumulative microtrauma risk.

Technique faults that raise low‑back risk include early spinal extension, excessive lateral flexion toward the target, and premature thoracic rotation that gets ahead of pelvic motion. These deviations increase anterior shear and endplate loading, contributing to stress reactions, discogenic pain and facet irritation. The table below maps several trunk/hip variables to their optimal patterns and potential injury consequences.

| Variable | Optimal Range / Pattern | Injury Implication if Deviated |

|---|---|---|

| Pelvic rotation | 40°-60° (backswing) | Reduced pelvis motion → increased lumbar shear |

| X‑factor | 10°-20° separation | Excess → too much torsion; too little → lost power |

| Lateral flexion | Minimal and controlled | Excess → unilateral facet overload |

Technique adjustments that maintain efficient energy flow while protecting the low back focus on restoring hip contribution and refining trunk control. Evidence‑based cues and practices include:

- Initiate pelvic rotation earlier during takeaway to prevent late trunk catch‑up.

- Preserve neutral lumbar posture through transition – avoid early extension or excessive rearward weight shift.

- Encourage lead‑hip internal rotation and trail‑hip extension during downswing so rotation is generated by the pelvis rather than the spine.

- Train GRF timing so vertical and horizontal impulses are applied through the hips first.

Prevention and correction should blend mobility, strength and motor‑control work: hip rotation ROM, gluteal and trunk rotator endurance, and reactive sequencing drills that mimic high‑speed loading. clinical screens – single‑leg rotational strength tests, hip ROM measures and movement pattern checks – help identify golfers at higher risk. Gradual loading plans, targeted eccentric trunk conditioning and wearable load monitoring support objective control of cumulative lumbar exposure while preserving performance improvements.

Temporal Variability, Motor Learning, and Principles for Individualized Technique Refinement

Modern perspectives view temporal variability not simply as error but as a functional element of skilled movement. Research indicates that elite performers maintain consistent relative timing of task‑critical events (for example, peak clubhead velocity near impact) while allowing variability in absolute durations across swings. This pattern underpins the idea of temporal invariants – coordinative structures that stabilize what matters for task success while permitting flexibility to adapt. Distinguishing systematic inter‑trial timing changes from within‑swing jitter helps diagnose whether variability stems from learning, fatigue or compensatory strategies.

Neuromuscular sequencing shapes these timing patterns: the phasing of muscle activations across trunk, hips and forearms determines whether key kinematic targets are achieved. Objective measures such as standard deviation of backswing time, coefficient of variation for downswing initiation, and EMG onset latencies provide quantifiable indices of temporal control. Moderate variability – termed functional variability – often correlates with adaptability, whereas excessive dispersion suggests instability and higher injury risk. Coaches and scientists should therefore aim for consistency in task‑relevant elements and accept exploratory variation in non‑critical components to preserve adaptability.

- Assess timing profiles using both kinematic (motion capture, IMUs) and neuromuscular (EMG) tools to determine which elements are stable and which fluctuate.

- prescribe practice that alternates constrained repetition (to reinforce invariants) with variable practice (to enhance transfer).

- adjust feedback frequency – give augmented feedback early, then taper it to promote self‑association.

- Personalize tempo cues based on the athlete’s timing profile rather of imposing a one‑size‑fits‑all cadence.

Individualized technique development begins with diagnostic profiling followed by focused interventions. A practical profile might report: (a) mean and variability of backswing and downswing durations, (b) timing of pelvis‑thorax separation, and (c) sequence of peak segment velocities. Interpretation must factor in physical constraints (e.g., hip ROM, trunk rotational strength) and performance priorities (accuracy versus distance).Training should be hypothesis‑driven: if downswing initiation is highly variable but impact timing is stable, emphasize drills that restore consistent initiation cues while preserving impact invariants. If impact timing itself is inconsistent, then retraining hierarchical proximal‑to‑distal sequencing and neuromuscular timing becomes the central task.

| Temporal Metric | Typical Range | Coaching Cue |

|---|---|---|

| Backswing Duration (ms) | 700-1100 | “Smooth to top” |

| Downswing Duration (ms) | 150-260 | “Accelerate through” |

| Impact Window SD (ms) | ±5-25 | “Narrow the window” |

Use brief tables like the one above during athlete debriefs to translate biomechanical metrics into coachable language; these simplified benchmarks help guide rapid choices and monitor progress.

Objective Assessment Methods: Motion Capture, Force Platforms, and Wearable Sensor Integration

Optical motion capture remains the reference standard for precise, three‑dimensional kinematic assessment of the golf swing. Marker‑based systems sampled at ≥200 Hz track segment rotations, intersegment coupling and club trajectories with high spatial fidelity. When used with anatomically appropriate marker sets and functional joint calibration,they enable accurate derivation of joint centers and joint angles needed to diagnose swing plane deviations and sequencing faults. however, marker occlusion, soft‑tissue motion and lab constraints reduce ecological validity, so motion capture outputs should be considered alongside kinetics and field measures.

Force platforms provide direct measures of GRFs, moments and center‑of‑pressure patterns that underpin balance, load transfer and impulse generation. Time‑resolved GRF traces disclose weight‑shift timing, lateral force production and braking/propulsive phases that influence clubhead speed. Combining plate data with inverse dynamics allows estimation of net joint moments and power flow across lower limbs, pelvis and trunk – metrics useful for spotting inefficiency and asymmetry linked to injury. High‑quality, multi‑axis force plates with fast sampling rates deliver the most reliable kinetic inputs for model‑based analysis.

Wearable systems – IMUs, pressure insoles and instrumented grip sensors – bring portability and on‑course relevance. Modern IMUs (accelerometer + gyroscope ± magnetometer fusion) estimate segment orientation and angular velocity where optical capture is impractical; pressure insoles measure plantar loading and COP migration; instrumented grips approximate forces at the club handle. These tools enable longitudinal and context‑specific testing but require careful calibration, drift correction and validation against laboratory standards to maintain data fidelity.

Multimodal assessment is most effective when data streams are synchronized and fused robustly to reconcile different sampling rates, coordinate frames and noise properties. Key integration steps include accurate time‑stamping and clock synchronization, coordinate alignment, resampling or interpolation, and sensor fusion (for example, complementary or Kalman filters). Practical implementations often rely on hardware triggers or network time protocol (NTP) alignment and then algorithmic fusion that weights optical kinematics for spatial precision and wearables for field robustness. This hybrid strategy leverages each modality’s strengths while minimizing individual weaknesses.

To guide method choice, the table below contrasts the modalities and their typical uses. Select sensors based on the principal outcome of interest (kinematics vs kinetics vs field monitoring), acceptable trade‑offs in portability, and the available analysis pipeline for integrating and interpreting the data.

| Modality | Key Metrics | Primary Strength | Common Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Optical Motion Capture | Joint angles, segment velocity | High spatial accuracy | Lab‑bound, marker occlusion |

| Force Platforms | GRF, COP, joint moments | Direct kinetic measurement | Requires controlled stance area |

| Wearable Sensors | Angular velocity, plantar pressure | Portability, field assessment | Drift, alignment/calibration needed |

Evidence‑Based Training Interventions to Enhance Performance and Mitigate Injury

Current evidence supports a multimodal approach that combines functional mobility (thoracic rotation, hip IR/ER), segmental stability (lumbopelvic and scapular control), and force‑velocity development (hip and trunk power) to produce consistent sequencing and higher clubhead speeds.Interventions should be driven by objective diagnostics – motion capture or IMU data for kinematic deficits, force plates or dynamometry for kinetic limitations, and validated clinical screens for neuromuscular control – so programming targets the mechanical contributors to an individual’s swing inefficiency or pain.

Effective programs blend tissue‑specific loading with task‑relevant motor learning to translate strength into swing performance. Recommended elements include:

- Dynamic mobility circuits – thoracic rotations, controlled articular rotations for the hip (CARs), and loaded hinge progressions to restore usable ROM.

- Strength and power work – bilateral/unilateral hip extension, rotational medicine‑ball throws and short‑lever Olympic variations to boost rate of torque development.

- Neuromuscular stability – anti‑rotation Pallof presses, single‑leg balancing with perturbations and scapular endurance sets to protect the shoulder‑thorax link.

Motor‑learning methods enhance transfer to the course. Favor an external focus of attention,variable practice contexts (different targets and clubs),and intermittent augmented feedback (short video clips or tempo cues) rather than constant verbal correction. Progress from high‑feedback, low‑speed drills to low‑feedback, full‑speed integration in periodized blocks to consolidate efficient sequencing while avoiding maladaptive compensations.

The table below distills high‑value,evidence‑informed interventions and their mechanical targets to help clinicians and coaches assemble individualized microcycles.

| Intervention | Mechanical Target | Expected Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| Eccentric hip loading | Deceleration control of pelvis | Lower low‑back shear; smoother pelvic rotation |

| Thoracic mobility + sequencing drills | Upper‑torso rotation capacity | Greater X‑factor; increased clubhead speed |

| Scapular stabilization protocol | Shoulder girdle resilience | Fewer shoulder problems; more stable contact zone |

Programs must be individualized and tracked. Use baseline and follow‑up assessments (kinematic metrics, force profiles, and patient‑reported measures) to quantify change and guide progression. Apply conservative load‑management when technical changes are introduced: brief, frequent exposures to the modified swing, objective caps on volume increases, and on‑course monitoring help prevent flare‑ups. The most successful interventions combine biomechanical diagnostics with structured, progressive training that emphasizes reproducibility, task specificity, and an ongoing feedback loop among coach, clinician and athlete.

Equipment Interaction and Environmental Factors Influencing Biomechanical Efficiency

Club design and fit systematically affect the kinematic chain. Shaft length,flex,grip size and lie angle change address posture and in‑swing joint geometry,altering moment arms and segment velocities. Properly fitted gear reduces compensatory motions – for example,excessive trunk tilt or premature shoulder rotation – enabling more direct transfer from pelvis to club. Fitting should therefore account for kinematic alignment (address posture and swing plane) along with standard ball‑flight outcomes.

Specific equipment attributes influence launch mechanics and timing of force production. Head mass distribution, face stiffness and shaft torque interact with wrist and forearm torques to shape ball speed and spin. Representative effects and swift fit guidelines are summarized below:

| Equipment Element | Biomechanical Effect | Practical Optimization |

|---|---|---|

| Longer shaft | Greater potential clubhead velocity; shifts swing moment | Fit to player height and tempo; check stability |

| Softer shaft | Delays peak velocity and can change timing | Match to load pattern and release point |

| Low CG head | Higher launch, lower spin tendencies | Consider for slower swings or higher launch needs |

Environmental and surface factors also force biomechanical adjustments. Key variables include:

- Wind: Changes aerodynamic forces and may prompt tempo adjustments or different club selection to control trajectory.

- Temperature/air density: Cooler or denser air shortens carry distance and can encourage greater maximal effort from the kinetic chain.

- turf firmness and slope: Affect traction and GRF vectors, requiring stance and weight‑distribution modifications.

Integrating equipment and environmental considerations requires a data‑lead approach. Combine kinematic capture, GRF analysis and launch monitor outputs to quantify how a club or condition alters joint loads and sequencing.Small changes – grip size, sole geometry or footwear – can redistribute stresses across lumbar spine, hips and knees; therefore optimize equipment with both performance and injury risk in mind. Validate prescriptive changes under the competitive conditions the player will face to ensure ecological relevance.

Q&A

Q1. What does “biomechanical analysis” mean for the golf swing?

A1. Biomechanical analysis uses mechanics to quantify and interpret how a golfer’s body and club move and interact. It covers kinematics (positions, velocities, accelerations), kinetics (forces, moments, ground reaction forces) and neuromuscular activity (timing and magnitude of muscle activation) to explain performance drivers and injury mechanisms. This approach aligns with standard definitions of biomechanics and human movement science (see referenced overviews).

Q2. What phases of the swing are typically used in biomechanical studies?

A2. Researchers frequently enough segment the swing into setup (address),backswing,transition/downswing initiation,acceleration toward impact,impact,and follow‑through (deceleration). These landmarks help locate timing of kinematic events, kinetic peaks (for example, GRF maxima), and neuromuscular onsets.

Q3. Which kinematic variables best inform swing assessment?

A3. Notable kinematic metrics include joint angles (thorax, pelvis, shoulder, elbow, wrist), angular velocities and accelerations (notably trunk and lead‑arm rotation), sequencing/timing, clubhead speed and path, face orientation at impact, and coordination indices such as X‑factor.

Q4. Which kinetic measures are crucial in swing biomechanics?

A4. Key kinetic variables are ground reaction forces (vertical and shear), joint moments and powers (hip, lumbar spine, shoulder, elbow, wrist), net external moments on the club, and body‑club impulse transfer. Inverse dynamics integrates motion and force data to estimate internal joint loading.

Q5. How do neuromuscular dynamics influence an effective swing?

A5. Neuromuscular factors include activation timing and magnitude, intermuscular coordination and use of stretch‑shortening cycles. Effective swings show ordered activation from proximal (hips/trunk) to distal (shoulder/arm/forearm) timed to optimize sequential energy transfer; EMG is a direct method to observe these patterns.

Q6. What is the typical proximal‑to‑distal sequence and why is it important?

A6.Efficient sequencing usually runs pelvis → thorax → lead arm → club. This order promotes angular momentum transfer to distal segments, boosting distal angular velocity while minimizing energy loss.Disruptions lower clubhead speed and can concentrate stress on specific joints.

Q7. How is clubhead speed generated and what factors most affect it?

A7. Clubhead speed results from the summation of segmental angular velocities through coordinated rotation and translation.Influential factors include trunk rotational speed, X‑factor stretch and recoil, lower‑limb ground reaction forces, proper sequencing, and wrist/forearm mechanics near impact. Strength, power and neuromuscular timing set the ceiling for achievable speed.

Q8. What measurement technologies are used in golf‑swing biomechanics?

A8. Typical tools include 3‑D optical motion capture, IMUs, force plates, instrumented club handles, high‑speed video, surface EMG and pressure mats. Inverse dynamics uses kinematic and force data to estimate joint kinetics.

Q9. What are the main injury risks tied to swing mechanics?

A9. frequent injury sites include the lumbar spine, shoulder (rotator cuff, labrum), medial elbow (golfer’s elbow) and wrist. Mechanisms include repetitive torsion on the spine, excessive lateral bending or shear, abrupt decelerations, asymmetry, poor sequencing and insufficient muscular capacity.Q10. How do mechanics contribute to low‑back injury?

A10. Low‑back risk increases with repetitive torsional and shear forces during fast trunk rotation, particularly when combined with lateral flexion and compression. Contributing factors include limited hip rotation, poor pelvis‑thorax dissociation, abrupt transition timing and exaggerated swing postures. Repeated exposure without recovery or motor‑control support elevates injury probability.

Q11. What conditioning or movement interventions reduce injury risk without harming performance?

A11.Effective interventions include improving hip and thoracic mobility, strengthening core and hip extensors for force production and spinal stabilization, neuromuscular training for timing and coordination, and eccentric/deceleration work for follow‑through control. Technique adjustments that reduce harmful postures, paired with progressive conditioning, can boost performance and lower injury risk.

Q12. How should coaches apply biomechanical findings in instruction?

A12. Coaches should use evidence‑based cues targeting the player’s specific deficits (sequencing, hip rotation, lateral bending), supported by objective measures where feasible (video, launch monitors, wearables). Interventions should be individualized to the player’s capacity, include mobility and strength work, and manage exposure to high‑load practice with monitoring for fatigue and pain.

Q13. What role does fatigue play in swing biomechanics and injury?

A13. fatigue disrupts neuromuscular control and kinematics, often degrading sequencing, increasing variability and producing compensatory motions that heighten joint loads and injury risk. Monitoring fatigue and prescribing appropriate rest and conditioning helps mitigate these effects.

Q14. Are there sex‑ or age‑related biomechanical differences relevant to coaching?

A14. Yes. Aging typically reduces strength, power and joint mobility, altering sequencing and lowering clubhead speed; sex differences in body proportions, muscle distribution and ROM can affect technique and loading patterns. Coaching and conditioning should be tailored to these individual differences across the lifespan.

Q15. What methodological issues and limitations are common in golf‑swing biomechanics research?

A15. Challenges include limited ecological validity (lab vs on‑course), soft‑tissue artifact in marker data, heterogeneity across participants (skill, equipment), small samples, cross‑sectional designs that limit causal inference, and overreliance on single outcome measures (e.g., clubhead speed). Stronger studies combine multiple measures, use longitudinal or interventional designs, and account for anthropometry and equipment.

Q16. How is inverse dynamics applied and what assumptions matter?

A16. Inverse dynamics estimates joint forces and moments from kinematics,segment masses/inertias and external forces. Assumptions include rigid body segments, accurate mass/inertia values, negligible soft‑tissue artifact and tightly synchronized force and motion data. Violations of these assumptions can bias kinetic estimates, so sensitivity checks and careful preprocessing are essential.Q17. What are evidence‑based training priorities to raise clubhead speed?

A17.priorities include rotational power work (medicine‑ball throws, rotational Olympic lifts), lower‑limb strength and plyometrics to maximize GRF, trunk and hip mobility to allow a considerable X‑factor and proper sequencing, neuromuscular drills reinforcing proximal‑to‑distal timing, and sport‑specific overload training that safely increases swing speed while monitoring technique.

Q18. How can wearable tech and launch monitors be used in biomechanical assessment?

A18. IMUs, pressure insoles and launch monitors provide field‑useable kinematic and outcome measures (clubhead speed, attack angle, ball speed), enabling longitudinal tracking and fatigue detection and supporting near‑real‑time biofeedback. For rigorous biomechanical interpretation, combine these data with periodic lab assessments (motion capture, force plates, EMG) to validate and calibrate wearable outputs.

Q19. What promising research directions exist in golf‑swing biomechanics?

A19. Promising areas include longitudinal interventions linking biomechanical changes to performance and injury outcomes; subject‑specific musculoskeletal modeling for load prediction; machine‑learning approaches to classify injury risk and optimize technique; validated field wearables for large‑scale monitoring; and studies of neuromechanical adaptation across skill levels and age groups.

Q20. What practical takeaways should clinicians and coaches use?

A20. Practical recommendations:

– Screen mobility, strength and movement patterns before changing technique.

– prioritize hip and thoracic mobility and core stability to protect the lumbar spine.

– Favor cues that enhance sequencing rather than only increasing rotation magnitude.

– Implement progressive strength and rotational power programs while monitoring asymmetry and fatigue.

– Use objective measures (video, launch monitors, force data when available) alongside individualized coaching and periodized conditioning.

– Refer golfers with persistent pain for medical evaluation before resuming high‑load practice.

Q21. How should biomechanical studies report results to maximize reproducibility?

A21. Reports should include detailed participant descriptors (skill, anthropometrics), instrumentation and equipment details (sampling rates, calibration), marker/segment definitions, data processing workflows, statistical methods and measures of variability. Sharing raw or processed data when possible and noting limitations in ecological validity and generalizability strengthens utility.

References and foundational sources

– For general context on biomechanics and human movement science, see introductory overviews that define scope and methods relevant to golf biomechanics [1-4].

If useful, additional deliverables can be prepared:

– A condensed Q&A focused specifically on coaching or injury prevention.

– Field‑kind screening checklists or visual aids for on‑course assessment.

– A curated bibliography of primary research studies in golf‑swing biomechanics.

Concluding Remarks

this review synthesizes kinematic, kinetic and neuromuscular perspectives to show how coordinated sequencing, targeted force production and timely muscle activation underpin both effective and safe golf swings. Viewing the swing through a biomechanical lens – where anatomical constraints and mechanical demands interact – highlights how relatively small adjustments in joint angles, ground‑reaction strategies or neuromuscular timing can meaningfully change ball flight and tissue loading.

For practitioners and investigators, two translational priorities emerge. First, objective measurement (high‑speed motion capture, force plates, wearable IMUs and surface EMG) supports evidence‑based technique changes and focused conditioning programs that aim to maximize energy transfer while controlling injurious loads. Second, individualized assessment – accounting for anthropometry, prior injury and skill level – should guide coaching decisions rather than relying on universal prescriptions.

limitations remain: much evidence comes from controlled laboratory settings that may not capture on‑course variability; participant samples are often heterogeneous and incomplete across age, sex and competition level; and direct interventional evidence linking specific biomechanical changes to long‑term performance or lower injury rates is still emerging.Addressing these gaps requires more longitudinal and randomized studies with ecologically valid protocols.

Future work should emphasize multimodal, field‑deployable measurement, integration of motor‑learning principles with biomechanical targets, and advanced analytics (including machine learning) to identify robust determinants of both performance and injury risk. Cross‑disciplinary collaboration among biomechanists, clinicians, coaches and engineers will accelerate translation of lab findings into scalable strategies for golfers of all levels.In short, a biomechanics‑driven approach – grounded in movement science – offers a pragmatic route to refine technique, increase performance consistency and reduce injury burden.Continued rigorous research and thoughtful translation into practice are keys to unlocking these benefits for the modern golfer.

Mastering the Golf Swing: A Biomechanical Guide to Power and Precision

Why biomechanics matters for your golf swing

Golf swing biomechanics isn’t just jargon – it’s the map that explains how your body generates speed, controls the clubface, and repeats quality shots under pressure. Understanding biomechanics helps you:

- Increase clubhead speed and ball distance efficiently

- Improve accuracy by controlling clubface orientation at impact

- Develop a repeatable, reliable swing sequence

- Reduce injury risk by moving within safe joint ranges and using the correct muscle groups

Key biomechanical principles (swift reference)

kinematic sequence – power from ground up

The most efficient swings transfer energy from the ground through the legs, hips, torso, arms, and finally to the club. A proper kinematic sequence times peak segment velocities so the hips rotate first, followed by torso, then arms and club. This sequencing maximizes clubhead speed with minimal wasted effort.

Ground reaction forces and weight transfer

Generating force against the ground (vertical and horizontal) allows you to push into the swing. Effective weight transfer from trail to lead side in the downswing contributes to power and stable impact positions.

Pelvis-shoulder separation (X‑factor)

Rotational separation between the hips and shoulders stores elastic energy in trunk muscles. Controlled, not forced, separation increases power while avoiding lumbar strain.

Angular momentum, moments and inertia

Creating rotational momentum around a stable axis increases clubhead speed. Managing moment of inertia (how weight distribution affects swing) and keeping the club on an efficient arc controls tempo and accuracy.

Clubface control & grip mechanics

Grip affects clubface orientation and release timing. Neutral, slightly strong, or slightly weak grips can be used strategically, but consistent grip and wrist hinge timing are critical to face control at impact.

Tempo, timing and rythm

Tempo (overall swing rhythm) and timing (when segments accelerate/decelerate) are foundational to repeatability. A stable head position and controlled transition support consistent timing.

Setup fundamentals: grip, stance and posture

- Grip: hold the club with light to moderate pressure. Check finger placement: lead hand V pointing to your lead shoulder, trail hand supporting and covering the knuckle alignment that fits your natural release.

- stance width: Shoulder-width for irons; slightly wider for woods and drivers. Wider stance aids stability for higher moment swings.

- Ball position: Center for short irons, slightly forward for mid-irons, just inside lead heel for driver to promote upward attack angle.

- Posture & spine angle: hinge at hips with a slight knee flex, spine tilted forward but neutral (avoid slouched posture).Maintain this static spine angle across the swing to preserve consistency.

- Balance & center of pressure: Slight weight on the balls of the feet. Avoid excessive lateral sway; rotate around your axis.

The swing phases – biomechanical goals and cues

Backswing

- Goal: Build stored rotational energy with controlled shoulder turn and stable lower body.

- Cues: “Turn the chest away,” maintain spine angle, allow natural wrist hinge.

- Common fault: Over-swing or excessive lateral movement – reduces ability to sequence correctly.

Transition

- Goal: Initiate downswing via ground and hip action (not by throwing the arms).

- Cues: “Feel the trail heel press,” or “start with the hips.”

- Common fault: Casting (releasing wrists early) – loses speed and control.

Downswing & impact

- Goal: Discover correct kinematic sequence – hips clear, torso follows, arms and club accelerate last into impact.

- Cues: “Lead with the hips,” “maintain lag” (keep wrist hinge until late), “square the clubface to the arc.”

- Metrics to watch: clubhead speed, ball speed, smash factor, strike pattern.

Follow-through

- Goal: Complete rotation with balanced finish.good follow-through is evidence of a well-sequenced swing and proper release.

- Cues: “Finish tall, chest over lead knee,” controlled deceleration of the club.

Common faults and biomechanical fixes

- early extension (standing up through impact): Improve hip mobility and practice drills that preserve spine angle (chair drill, wall drill).

- Sway rather of rotate: strengthen glutes and adductors; use step-through or alignment stick drills to promote rotation rather then lateral motion.

- Casting / early release: Wrist-hinge delay drills, impact bag practice, and pause-at-top drills train retention of lag.

- Over-rotated shoulders / pulled shots: Focus on rotational sequence and club path drills; ensure appropriate grip and hand position.

| drill | Purpose | Reps |

|---|---|---|

| Towel under lead armpit | Promote connected arms/torso rotation | 3 sets x 10 swings |

| Med-ball rotational throw | Develop explosive trunk rotation | 3 sets x 6 throws each side |

| Pause-at-top | Improve transition timing and lag | 5-8 swings |

| impact bag | Train correct impact feeling and compression | 4 sets x 8 hits |

| step-through drill | Encourage weight transfer and rotation | 3 sets x 8 |

Training, mobility and strength for swing power

Biomechanics needs support from strength and mobility. Key areas to prioritize:

- Rotational power: Med-ball throws, cable woodchops

- Hip & glute strength: Romanian deadlifts, hip thrusts

- Thoracic mobility: Foam roller rotations, thoracic extensions

- Core stability: Anti-rotation planks, Pallof presses

- Lower limb stability: Single-leg squats, lateral lunges

Frequency: 2-3 strength sessions per week plus daily mobility work. Always warm up dynamically before practice (leg swings, band rotations, light swings).

Measuring progress: tech & metrics to track

Use accessible metrics to objectively track biomechanical improvements:

- Clubhead speed (mph) and ball speed (mph) – direct indicators of power

- Smash factor (ball speed ÷ clubhead speed) – energy transfer efficiency

- Launch angle and spin rate – for optimal carry and roll

- Face angle & path (from launch monitor) – accuracy drivers

- Video & 2D/3D motion capture – analyze kinematic sequence and joint angles

Popular tools: launch monitors (TrackMan, GCQuad, Mevo), high-speed video, wearable inertial sensors, and motion capture for deeper analysis.

8-week practical practice plan (sample)

- Weeks 1-2: Fundamentals – setup, grip, posture, basic rotation drills. Light tempo swings, 3 sessions/week.

- Weeks 3-4: Transition & sequencing – pause drills, impact bag, med-ball rotational power. Add 2 strength sessions/week.

- Weeks 5-6: Speed and transfer – controlled overspeed swings (with coach guidance), weighted club swings, roational power work.

- Weeks 7-8: Integration & course request – full-swing to target,on-course practice focusing on shotmaking,use launch monitor to confirm gains.

Tips for coaches and advanced players

- Individualize: screens for mobility, strength and movement patterns (hip internal rotation, thoracic rotation, ankle mobility).

- Use objective feedback: integrate launch monitor metrics into practice to separate feel from reality.

- Progress drills: move from slow, purposeful movements to speed-focused training while preserving mechanics.

- Manage load: rotate high-intensity swing training with recovery and mobility days to prevent overuse injuries.

Injury prevention and recovery

Common golf injuries involve the lower back, wrist, elbow and shoulder. Biomechanical causes frequently enough include poor sequencing, insufficient hip rotation, or excessive lumbar loading. Preventive strategies:

- Address mobility deficits (hip and thoracic)

- Build posterior chain strength (glutes, hamstrings)

- Maintain balanced practice volumes with cross-training

- Use soft-tissue work and targeted rehab for problematic areas

Case study: applying biomechanical training (brief)

A mid-handicap player improved driver distance by 16 yards in 10 weeks after a program emphasizing kinematic sequencing, med-ball power work, and lag-retention drills. Key changes measured: +5 mph clubhead speed, improved smash factor, and tighter dispersion due to improved face control. The program combined technical swing drills,two weekly strength sessions and regular launch monitor feedback.

SEO & content tips for golf coaches, trainers and facilities

To reach golfers searching for biomechanical swing help, follow these SEO best practices:

- Use keyword phrases naturally: “golf swing biomechanics,” “increase clubhead speed,” “swing mechanics drills,” and long-tail queries like “how to create lag in golf swing.”

- Meta title & description: craft concise, benefit-driven meta tags (see top of this article).

- Local SEO: if you offer lessons, maintain your Google Business Profile with accurate hours, photos and reviews to boost local ranking.

- Keyword research: leverage tools like Google Keyword Planner to discover search volume and related queries for content planning.

- Analytics: track visitor behavior and conversion with platforms such as Google Analytics 4 to refine content and course offerings.

Practical quick drills and cues to try on the range today

- Towel under lead armpit: 10 reps to promote connection

- Pause-at-top: 5 slow swings to groove transition

- Med-ball side throw: 3 sets of 6 to build rotational power

- Impact bag: 3 sets of 8 to feel compression and face square

- Slow-motion mirror swings: 10 reps to check spine angle and rotation

Final coaching cues (short list)

- “Turn, don’t slide.”

- “Start the downswing with the hips.”

- “Keep the wrist hinge until late.”

- “Finish tall and balanced.”

If you’d like,tell me the target audience (beginners,coaches,or pro players) and I’ll tailor this article further – for example: simplified drills and explanations for beginners,programming and data-driven drills for coaches,or high-performance tuning for pros.