Precision metrology and disciplined analytic reasoning are prerequisites for meaningful progress in golf-equipment engineering and fitting. This article introduces an “analytical framework for Golf equipment Performance Metrics” that prescribes consistent definitions, measurement workflows, and interpretation strategies for the principal variables that determine on-course results-ball velocity, launch geometry, rotational rates, shot scatter, and effective range-while explicitly accounting for equipment geometry (head, shaft, grip), player-equipment coupling (swing kinematics and dynamics), and ambient conditions (temperature, barometric pressure/altitude, turf state). By codifying metric definitions,test procedures,calibration and uncertainty reporting,and model validation steps,the framework converts fragmented testing habits into a replicable,comparable,and decision‑ready evidence base for researchers,manufacturers,clubfitters,and high-performance coaches.

This methodology adapts best practices from other exacting domains where standardized protocols and transparent reporting produce reproducible characterization of intricate systems (for example,spectroscopic and separation techniques used to resolve fine structural equilibria in chemistry and biophysics). Applying these principles in golf demands the integration of high‑resolution instrumentation (radar and optical trackers, load cells, high‑speed imaging), rigorous signal processing and noise modeling, purposeful experimental designs for both controlled-lab and field collection, and statistical techniques that apportion variability between equipment, athlete, and surroundings. Central to the framework is explicit quantification of measurement uncertainty, bias control, calibration traceability, and interlaboratory comparability so that claimed performance changes are both statistically defensible and practically significant.

The following sections are organized to (1) present a taxonomy of performance metrics with precise operational definitions, (2) describe standardized measurement and sensor-fusion approaches, (3) outline analytical and statistical methods for parameter estimation and sensitivity checks, and (4) set validation, reporting, and integration criteria to guide design iteration and fitting workflows. Later parts apply the framework to common equipment classes, illustrate evidence‑lead decision processes, and consider regulatory, innovation, and research priorities for the field.

Theoretical foundations of Golf Equipment Performance Metrics and Measurement Validity

Modern evaluation of golf equipment should start from measurement science: clearly defined constructs and carefully operationalized metrics. Here, “theoretical” denotes the conceptual model that explains what a metric is intended to represent-distinct from how it is instrumentally captured-so that sensors and protocols align with the underlying construct rather than merely convenient outputs. Anchoring metrics in explicit theoretical models reduces interpretive ambiguity, supports cross-study comparability, and strengthens causal statements about how equipment properties affect ball trajectory and player biomechanics.

Performance indicators must be articulated as latent constructs before measurement. Typical core metrics include:

- ball speed: the linear speed of the ball promptly after impact, used as an operational proxy for energy transfer efficiency.

- Launch angle: the initial elevation of the ball’s velocity vector relative to the playing surface, which interacts with spin to determine carry and total range.

- Spin rate: the angular velocity about the ball’s axes (backspin and sidespin) that controls lift, descent profile, and on‑green behavior.

- Smash factor: the ratio of ball speed to clubhead speed at impact, reflecting impact efficiency.

- Dispersion: the spatial variability of shot endpoints, representing repeatability and directional control.

Validity and reliability of measurements must be evaluated across multiple axes: construct validity (does the quantity measure the intended attribute?), criterion validity (does it predict meaningful outcomes like carry distance?), and reliability (are observations stable under equivalent conditions?). the short table below pairs sample metrics with their conceptual targets and the main threats to valid measurement.

| Metric | target construct | Primary Validity Threat |

|---|---|---|

| Ball speed | Energy transfer | Temporal sampling or sensor lag |

| spin rate | Aerodynamic rotation | Inconsistent contact or measurement geometry |

| Dispersion | Shot repeatability | Environmental or procedural variability |

Threats to validity might potentially be systematic (bias) or random (noise) and originate from instruments, environment, or human factors. Typical culprits include launch‑monitor miscalibration, drift in camera timing, wind or temperature effects, inconsistent sensor placement, and golfer-related variability in setup or tempo.Mitigations focus on standardization (fixed test conditions where feasible),cross-device calibration,replicated trials to estimate variance components,and pre-registered measurement plans to constrain researcher degrees of freedom.

For applied research and product advancement the theory-driven approach yields practical prescriptions: use multimodal sensing to triangulate constructs, define clear inclusion/exclusion and preprocessing rules, publish reliability metrics and validity evidence, and update conceptual models as new empirical patterns appear. These practices produce not only precise measurements but metrics with practical meaning-facilitating translation from lab findings to on-course optimization and responsible product claims.

Key Quantitative Indicators for Club and Ball Performance with operational Definitions and accuracy Thresholds

Primary indicators should be framed with unambiguous operational criteria so results are comparable across instruments and labs. These typically include:

- Clubhead Speed: maximum linear velocity of the clubhead at impact (mph or m/s), captured by radar or high‑speed motion tracking; used to contextualize energy input.

- Ball Speed: post-impact linear speed of the ball, measured with Doppler radar or photometric sensors; the foremost predictor of travel distance.

- Smash Factor: the ball‑speed / clubhead‑speed ratio (dimensionless), computed as the average of the sample swings.

- Launch Angle: the vertical component of the ball velocity vector at departure (degrees), from high‑speed tracking solutions.

- Spin Rate: rotational velocity in rpm, partitioned into backspin and sidespin using radar or photogrammetric methods.

supporting indicators characterize control, energy fidelity, and equipment form factors:

- Carry and Total Distance: measured horizontal travel before first impact and combined roll; report under neutralized wind and defined turf conditions.

- Dispersion Metrics: lateral deviation and grouping statistics (SD of impact positions), separately for carry and final resting positions.

- Angle of Attack & Face Angle: club path and face orientation at impact (degrees), useful for diagnosing launch and spin causality.

- Coefficient of Restitution (CoR) & MOI: intrinsic ball/club properties that shape energy restitution and forgiveness; measured to laboratory standards.

Accuracy thresholds and operational tolerances set minimum precision for comparative work. Reasonable laboratory targets are:

- Ball Speed: ±0.5 mph (±0.22 m/s)

- Clubhead speed: ±0.2 mph (±0.09 m/s)

- Launch Angle: ±0.3°

- spin rate: ±50 rpm

- Smash Factor: ±0.01

- Carry Distance: ±1.0 yd (±0.9 m)

Measurements outside these tolerances should trigger recalibration or exclusion according to a pre-specified analysis plan.

Data quality controls and protocol requirements are essential to attribute observed differences to equipment rather than noise. Minimum procedural controls include:

- Instrument calibration against certified speed and spin references before each session.

- Environmental normalization (temperature, humidity, altitude) or model-based corrections.

- sample design: a recommended baseline of 20 valid strikes per club/ball combination per player or mechanical device to stabilize estimates.

- Pre-defined automated and manual outlier rules (e.g., mis-hits, data dropouts).

- Synchronized multi-sensor capture (radar + high-speed camera) where practical to cross-validate kinematics and ball-flight measures.

decision rules for practical significance convert metric shifts into actionable categories. Assuming measurements are within tolerance and environmental corrections applied, the table below gives pragmatic thresholds for interpreting controlled-test differences.

| Metric | meaningful Delta | Practical Classification |

|---|---|---|

| ball Speed | +1.0 mph (~+2.5 yd) | Moderate benefit |

| Smash Factor | +0.01 | Notable efficiency gain |

| Spin rate | ±200 rpm | Changes landing and stopping |

| Lateral Dispersion | ±0.5 yds | Material impact on accuracy |

Methodologies for Laboratory and On course Data collection Including Calibration and Quality Control Protocols

study design should bridge laboratory control and on‑course realism to deliver comparable, reproducible metrics. Standardized protocols for equipment conditioning, ball handling, and environmental logging ensure that lab repeatability translates into field relevance. Where relevant, governance models can mirror those used in diagnostic laboratories-emphasizing traceability, documented workflows, and specimen stability-to maintain cross-context validity.

Instrumentation should be chosen for functional fit, calibration capability, and documented performance envelopes. A typical toolkit includes:

- Laboratory-grade launch monitors mounted on controlled surfaces

- High-speed imaging arrays to capture impact kinematics

- Portable radar/GNSS systems for on-course trajectory tracking

- Force and pressure plates to quantify stance and ground-reaction dynamics

Each instrument should have an associated uncertainty statement, a calibration certificate, and a record of the environmental envelope (temperature, humidity, altitude) so later normalization and meta-analysis are possible.

Calibration schemes should be hierarchical and reference-based: primary standards, secondary working standards, and field check artifacts establish baseline performance. The example cadence below is illustrative and should be adapted to device criticality and observed drift patterns.

| Instrument | Reference standard | Calibration Frequency | Acceptable Drift |

|---|---|---|---|

| Launch Monitor | Certified ball velocity standard | Monthly (lab),Weekly (field) | ±0.5% speed |

| High-speed Camera | Frame-rate timing module | Quarterly | ±0.2 ms/frame |

| Radar/GNSS | Positional test beacon | Before each field session | ≤2 m positional error |

| Force Plate | Mass/force calibration weights | Monthly | ±1.0% force |

Quality control should be layered: internal control samples, blinded repeats, and external proficiency comparisons maintain integrity. Use control charts for drift detection,predefined acceptance thresholds,documented corrective actions,and scheduled proficiency exercises with self-reliant advisers. Keep an auditable QC record to support replication and stakeholder review.

Data governance and validation complete the protocol stack: capture metadata (instrument IDs, calibration state, operator, environment), implement automated outlier flags, and retain both raw and processed data for reanalysis. Prioritize data traceability via immutable audit logs and checksum verification; conduct periodic integrity audits and version-controlled algorithm validations. Recommended operational practices include:

- Routine cross-validation between lab and field datasets

- periodic external review by an independent laboratory advisory group

- Documented change control for firmware and data-processing pipelines

These practices ensure equipment metrics are robust, defensible, and suitable for high‑stakes comparative analyses.

Statistical Modeling Approaches Connecting Equipment characteristics to Shot Dispersion and Scoring Outcomes

Large repositories of shot-level telemetry enable principled estimation of causal links between equipment design and on-course variability.Treat each shot as an observation and nest shots within rounds and players to apportion variance to the club (geometry, shaft), the ball (compression, spin profile), the player (tempo, attack angle), and context (wind, lie, turf firmness). High-frequency covariates such as clubhead speed and impact location create explanatory features that predict both central outcomes (carry,total distance) and distributional characteristics (SD,skewness,tail probabilities for extreme misses).

Robust inference benefits from complementary modeling paradigms. Mixed-effects models represent hierarchical data (shots → rounds → players) and isolate fixed equipment effects; Bayesian hierarchical models allow incorporation of prior knowledge (manufacturing tolerances, expected spin distributions) and provide full posterior uncertainty for decision-making; Gaussian process models capture complex non-linear surfaces relating design parameters to dispersion under varying launch conditions. Practical workflows combine these approaches with regularization (L1/L2 or shrinkage priors) and resampling-based validation. Crucial modeling choices include:

- Choice of likelihood: Gaussian for continuous dispersion metrics, Student‑t for heavy-tailed errors, and Tobit models for censored observations.

- outcome specification: predict dispersion (SD, IQR), directional bias (mean lateral offset), and tail risk (probability of >20‑yard misses).

- Feature interactions: capture cross-effects such as clubhead speed × shaft flex or loft × spin rate to model conditional heteroskedasticity.

translating abstract equipment metrics into interpretable performance descriptors is essential for designers and coaches. The illustrative mapping below summarizes empirical associations commonly observed in tracking studies; these should be estimated conditional on player skill and launch conditions, not assumed universal.

| Equipment Metric | Primary Dispersion effect | Scoring Implication |

|---|---|---|

| MOI (high) | Reduced lateral dispersion | fewer penalty shots from big misses |

| Loft consistency | Lower SD of carry distance | Tighter approach proximity |

| Spin rate variability | Increased short‑game dispersion | Greater variance in scrambling opportunities |

| Shaft torque/flex | Conditional lateral bias at high speed | Changes in expected GIR frequency |

when modeling scoring outcomes, discrete and ordinal frameworks are appropriate: logistic regression for birdie/save probabilities, Poisson or negative‑binomial models for stroke counts, and cumulative link models for hole score categories. Counterfactual simulations that hold course state and player ability constant while varying equipment parameters provide actionable estimates of expected strokes saved and variance reductions. Validate models by checking calibration (e.g., reliability diagrams) and decision-focused metrics (expected utility of equipment changes for specific player segments), and always present uncertainty bounds so technicians and coaches can weigh robustness against peak performance.

evaluating Risk Reward Tradeoffs of equipment Choices Across Course Conditions and Player Skill Profiles

Frame equipment choice as a trade‑off between average performance gain and increased outcome variance under diverse course conditions. Treat club and ball characteristics (loft,MOI,COR,spin profile) as inputs to a stochastic shot generator to estimate central tendency measures (mean carry,average dispersion) and tail statistics (95th‑percentile miss distance,penalty probability). These distributional summaries make it possible to compare items that offer similar headline distance but differ substantially in downside exposure when wind, firmness, or rough amplify small errors.

The computational approach centers on expected strokes gained per shot conditioned on situational states and player error models. Monte Carlo simulations calibrated to launch‑monitor cohorts compute conditional expectations and variances for candidate setups. A compact reference of archetypal trade‑offs commonly used in such analyses is below:

| Equipment | Typical Reward | Typical Risk |

|---|---|---|

| Low-spin Driver | More roll (+15-25 yd depending on firmness) | Greater sensitivity to crosswinds; elevated dispersion |

| Forgiving Iron | Consistent carry | Reduced shot-shaping capability |

| High-bounce Wedge | Improved play in soft turf | Less precision on tight, firm lies |

- Parameter estimation: derive player‑specific dispersion and launch parameters from repeated-shot traces.

- Scenario simulation: generate rounds across matrices of course states (firm/soft, wind vectors, rough severity).

- Risk metrics: compute expected strokes and downside measures (conditional value‑at‑risk,penalty probability).

- decision rule: optimize equipment selection against a utility function reflecting player risk preference.

Translate analytical outputs into player archetypes: aggressive, low‑dispersion long‑hitters may benefit from higher‑variance, high‑reward gear; players with wide dispersion typically gain more from forgiving, stability‑oriented clubs. The framework formalizes this mapping by introducing a risk‑aversion parameter (λ) into the optimization: maximize E[strokes saved] − λ·DownsideRisk. Course typologies (e.g.,wind-exposed) amplify downside multipliers and shift optimal solutions toward conservative equipment for players with moderate to high λ.

Empirical validation and iterative refinement are indispensable. Run A/B field protocols where option setups are trialed over matched hole sequences and compare outcomes with hierarchical models controlling for day‑to‑day variance.Instrumented monitoring (launch monitor + GPS + wind logs) enables continuous recalibration of the stochastic model; practitioners should focus on reducing tail risk for players who show high round‑to‑round volatility and consider measured risk increases for those with consistent shot shape control. The central proposal is to pair statistical decision rules with on‑course sensitivity testing rather than relying solely on distance claims.

Integrating Biomechanical, Launch Monitor, and Environmental Data for Personalized Equipment Recommendations

Modern fitting requires holistic fusion of motion‑capture biomechanics, high‑fidelity launch‑monitor outputs, and environmental context to produce prescriptions that are mechanistically sound and operationally useful.By linking kinematic chains (joint angles, segment velocities), kinetic signatures (ground reaction forces, torques), and temporal markers (tempo, transition timing) with ball‑flight outputs (ball speed, spin, launch, smash) under session conditions (wind vectors, air density, temperature, altitude), fitters can describe a player’s realistic performance envelope rather than a single momentary snapshot.

Operationalizing this fusion needs a robust analytical pipeline: precise synchronization of heterogeneous sensors, resilient preprocessing to minimize noise, and extraction of physiologically and mechanically meaningful features. Key pipeline elements include:

- Time alignment (precise motion-to-ball contact timestamping)

- Feature engineering (peak segment velocity, club path curvature, vertical launch)

- modeling (physics-informed regressions, mixed-effects models, or supervised machine learning)

- Constraint enforcement (anatomic limits and equipment tolerance boundaries)

Mapping these features to equipment choices is performed via multi‑objective optimization where trade‑offs are explicit (distance vs dispersion, spin vs landing stability). The example table below shows how measured variables typically translate into succinct equipment implications:

| Measured Variable | Typical Range | Equipment Implication |

|---|---|---|

| Peak Clubhead Speed | 75-120 mph | Optimize loft; consider stiffer shafts above ≈105 mph |

| Launch Angle | 8°-18° | Adjust driver loft or shift CG to reach target window |

| Spin Rate | 1,800-3,500 rpm | Surface and face design choices to tune spin up or down |

| Wind & Altitude | Session-calibrated | Dynamic yardage correction; consider loft changes in thin air |

Ensure robustness by cross‑validating predictive models on held‑out swings, validating on course across environmental gradients, and updating player‑equipment posteriors as new data accumulate. Account for sensor error and session variability; present confidence intervals around predicted gains to avoid overfitting specifications to transient swings. Document calibration, sampling rates, and alignment steps to support reproducibility.

for field implementation, surface model outputs in coach‑facing interfaces that emphasize actionable recommendations and transparent rationale.recommended deliverables include:

- Specific club spec list (loft, shaft model/length/flex, lie)

- Target launch window and acceptable dispersion bands

- Environmental adjustment rules (altitude and wind guidance)

- Drill-based prescriptions to align a player’s biomechanics with recommended specs

Embedding these deliverables into standard fitting workflows enables iterative refinement of the equipment-player match while preserving a transparent link between measured biomechanics, predicted ball flight, and playing conditions.

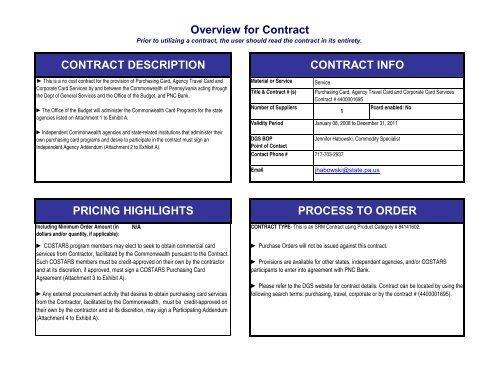

Standardization and Reproducibility in cross Brand Comparisons and Test Reporting

Comparisons across manufacturers demand strict controls so differences reflect product behavior rather than testing variability. without a shared framework, observed performance gaps can be artifacts of protocol inconsistencies. Standardization is therefore a methodological necessity and the foundation for defensible cross‑brand claims, enabling practitioners to disentangle systematic effects from measurement noise.

Vital elements of a robust test schema include explicit metric definitions,traceable calibration,and deterministic sample handling. Specify precisely how metrics are computed (time windows, filtering, smoothing), ensure instruments are traceable to calibration references, and adopt sample conditioning protocols (ball rotation, number of strikes, shaft/lie matching) to reduce intra‑sample variance and improve cross‑brand validity.

Transparent reporting accelerates reproducibility and critical review. Minimum reporting should include:

- Device and firmware details (manufacturer, model, firmware/build number)

- Environmental conditions (temperature, humidity, indoors/outdoors, surface type)

- Test protocol (trial count, rest intervals, swing replication method)

- Data processing (filtering steps, outlier rules, averaging)

- Statistical treatment (confidence intervals, effect sizes, hypothesis tests)

| Metric | specification | Tolerance |

|---|---|---|

| Ball speed | measured at 1.0 m post‑impact (m/s) | ±0.3 m/s |

| Launch angle | Peak loft relative to ground (deg) | ±0.5° |

| Spin rate | Backspin measured 2 m from impact (rpm) | ±50 rpm |

Statistical discipline completes standardization. Use repeated‑measures designs where feasible, report 95% confidence intervals and standardized effect sizes, and pre-register test plans. Openly sharing raw datasets and analysis code when possible supports independent replication and enables future meta‑analysis. These practices convert isolated comparisons into accumulating, generalizable knowledge about equipment performance.

Implementation Guidelines for Translating Performance Metrics into Fitting Practices and strategic Selection

Translating quantitative metrics into fitting decisions starts with validating what each KPI genuinely measures. Practitioners should routinely ask: what construct does this KPI represent? Only metrics with demonstrated construct validity (for example, dispersion as a proxy for ball‑flight control, smash factor as energy transfer) should dictate fitting choices. Create a measurement hierarchy that separates primary outcome metrics (distance, dispersion, launch consistency) from secondary process metrics (clubhead speed, attack angle) and codify acceptable ranges and confidence intervals before selection.

Standardized capture protocols preserve comparability and reduce noise: use consistent surfaces, ball models, and calibrated launch monitors for baseline captures, then normalize results for environmental variation.Key procedural controls include:

- Calibration cadence: daily/weekly checks of launch-monitor accuracy

- Repetition rules: minimum shot counts (e.g., 10-20 swings per club) and pre-specified outlier handling

- player state controls: warm-up requirements and fatigue monitoring

Decision pathways should map metric signatures to specific fitting interventions. Use compact decision tables so fitters can apply rules reproducibly during sessions. Example:

| Metric | Indicative Finding | Fitting Action | Decision Threshold |

|---|---|---|---|

| Carry Dispersion | High lateral scatter | Adjust lie/loft or recommend more forgiving head | Stdev > 12 yds |

| Smash Factor | Low energy transfer | Trial stiffer/softer shaft options | < 1.45 |

| launch Angle | Too low for desired spin | Increase loft or alter attack angle | Deviation from optimal > 2° |

Adopt an iterative advancement workflow-diagnose,prescribe,test,review. After applying a fitting change, collect follow-up data under the same protocol and compare against baseline with pre-planned tests or effect‑size criteria. Maintain a log for each player documenting hypotheses, interventions, and outcomes so fitting evolves as an evidence-based learning cycle rather than a set of ad hoc adjustments.

Embed governance and capability‑building to sustain translation. Train fitters in metric interpretation and in communicating trade-offs to players; align procurement and selection policies with KPI‑driven profiles; and schedule periodic KPI audits similar to performance‑review cycles to check which metrics remain predictive of on‑course success.By combining rigorous measurement,rule‑based decisions,iterative validation,and organizational alignment,the framework converts raw performance data into well‑justified club specifications and strategic selection.

Q&A

Below is a professional, academic-style Q&A to accompany the article “Analytical Framework for Golf Equipment Performance Metrics.” The Q&A clarifies central concepts, measurement approaches, analytical choices, and implications for applied fitting and research.

1) What is the purpose of an analytical framework for golf equipment performance metrics?

Answer: The framework organizes metric definitions, measurement procedures, experimental designs, statistical analyses, and reporting standards needed to assess how clubs, shafts, balls, and grips influence shot outcomes. It ensures comparisons are valid, reproducible, and interpretable across laboratory and field contexts, and it supports optimization for players and designers while respecting regulatory boundaries.

2) Which primary performance metrics should the framework include?

Answer: Core metrics include clubhead speed, ball speed, smash factor, launch angle, spin rate (backspin and sidespin), spin axis, launch direction (azimuth), carry and total distance, lateral dispersion, apex and descent angles, and impact location. For equipment characterization also record MOI, CG coordinates, face stiffness/COR maps, shaft dynamic properties (frequency, torque, bend/kick point), and grip dimensions.

3) How should these metrics be measured and what instrumentation is recommended?

Answer: Use validated launch monitors (Doppler radar or photometric/optical systems) together with high‑speed video and strain/accelerometer instrumentation for club dynamics as needed. Instruments must be calibrated and have quantified precision and accuracy. Club/shaft properties are best measured on mechanical rigs, 3‑D coordinate measurement systems, and modal analysis apparatus.

4) What experimental design principles are required for rigorous evaluation?

Answer: Use controlled conditions to minimize confounds (consistent ball type, temperature, humidity, and surface). Randomize equipment order, collect enough repetitions per subject-equipment pairing to estimate within‑subject variability, and employ within‑subject or matched designs to control for player skill. Report sample sizes, power calculations, and inclusion/exclusion rules; include diverse skill levels when generalizability is desired.

5) How should impact location variability be handled?

answer: Capture impact location for every shot (impact tape, high‑speed camera, or launch‑monitor mapping) and either analyze only centered strikes or include impact annulus as a covariate. Report results stratified by impact region since off‑center hits considerably alter ball speed,spin,and dispersion.6) Which statistical analyses are appropriate?

Answer: Mixed‑effects models with random effects for player and session partition variance; ANOVA/MANOVA test equipment differences across correlated outcomes; regression models predict continuous outcomes; PCA or factor analysis reduce dimensionality. Use cross‑validation and report out‑of‑sample performance; always provide effect sizes and confidence intervals in addition to p‑values.

7) How should measurement uncertainty be quantified and reported?

Answer: Provide instrument repeatability and accuracy for each metric, plus within‑ and between‑subject standard deviations, standard errors, and coefficients of variation. When modeling,propagate measurement error into estimates or use measurement‑error models. Transparently state filtering and exclusion criteria.

8) What role does biomechanical coupling (player‑equipment interaction) play in analysis?

Answer: Equipment effects are inextricably linked to the player. Model interaction effects (e.g., shaft flex × tempo). Include biomechanical measures where possible and cluster players by swing archetype to refine fitting guidance.9) How are trade‑offs between metrics handled (e.g., distance vs. accuracy)?

Answer: Apply multi‑objective optimization and Pareto analyses to identify setups that balance distance and dispersion. Use utility functions tuned to player priorities (handicap, stroke index) to make selections.

10) How should compliance with rules (USGA/R&A) be integrated into the framework?

answer: Treat regulatory limits (COR, groove rules, club length) as hard constraints in optimization and testing.Report proximity to conformity limits and include conformity testing in development pipelines.

11) What data reporting standards should be adopted to promote reproducibility?

answer: Publish full methods: ball/equipment models,environment,player demographics,trial counts,instrumentation and calibration details,impact‑location distribution,and preprocessing steps. Share raw or anonymized datasets and code where feasible.

12) Can machine learning be used within this analytical framework? If so, how should it be applied responsibly?

Answer: Yes. ML can model complex, non‑linear relationships for prediction and clustering. Use robust cross‑validation, guard against overfitting, prefer interpretable models or provide explainability analyses, validate across independent cohorts, and report generalization metrics.

13) How should researchers address environmental and ball variability?

Answer: Control ball model and condition, rotate or use new balls, and log ball model explicitly. Record environmental conditions and include them as covariates or apply correction models. Quantify and correct systematic biases across settings.

14) What protocols are recommended for shaft and clubhead characterization?

Answer: For shafts measure static and dynamic bend profiles, fundamental frequencies, torque, and mass distribution. For heads measure 3‑axis CG,MOI,face stiffness mapping,and mass properties. Use standardized rigs and report uncertainties; relate physical parameters to on‑ball outcomes via multivariate analysis.

15) How should dispersion be characterized and compared across equipment?

Answer: Report absolute dispersion measures (SD of carry and total, lateral RMS) and probabilistic metrics (95% confidence ellipse, miss‑distance percentiles). Translate dispersion into expected strokes gained under a course model to express practical impact.

16) What are best practices for translating analytical outcomes into fitting or design recommendations?

Answer: Build player‑specific models to identify equipment parameter regions that improve task‑relevant metrics. Provide quantified expected benefits and uncertainty, prioritize robust gains across likely impact locations and conditions, and favor changes that generalize beyond a single session.

17) What open research questions and future directions remain?

Answer: Important directions include: (a) stronger models of player‑equipment coupling across diverse populations; (b) biomechanically grounded predictive links from design variables to outcomes; (c) standards for impact mapping and face deformation under realistic loads; (d) wearable sensing for in‑play equipment assessment; and (e) open datasets for benchmarking predictive methods.

18) How should ethical and commercial considerations be balanced in academic studies?

Answer: Disclose funding,conflicts of interest,and proprietary tools; protect participant welfare and obtain informed consent. Preserve analytical independence in industry collaborations and, when feasible, share anonymized data and protocols to permit third‑party evaluation.

Summary recommendation: Adopt a rigorous, reproducible workflow combining validated instrumentation, controlled experimental design, mixed‑effects statistical modeling, explicit uncertainty quantification, and clear reporting. Use biomechanical measures to model player‑equipment coupling and multi‑objective optimization to convert metrics into actionable choices for players and designers.

If you would like, I can: (a) draft standardized measurement and reporting templates for a laboratory study, (b) produce statistical model code snippets (mixed‑effects model, PCA) for analyzing shot datasets, or (c) prepare a practical checklist for club‑fitting sessions aligned with this framework. Which would be most useful?

To Wrap It Up

The analytical framework described here offers a coherent pathway for characterizing and comparing golf equipment across the multidimensional performance space that shapes modern play. By defining clear metrics, prescribing measurement protocols, and integrating kinematic, aerodynamic, and material property data, the framework supplies a reproducible basis for scientific study and evidence‑driven product selection.Its focus on calibration, uncertainty quantification, and sensitivity analyses makes inferences about accuracy, distance, and consistency transparent and defensible.

lessons from other analytical sciences underscore the benefits of this approach: evolving instrumentation and methods increase the detectability and precision of key performance signals; comprehensive characterization techniques reveal subtle states that matter for performance; and attention to sample preparation and standardized assays reduces bias and improves inter-study comparability. Applying these methodological principles to the golf‑equipment domain will raise the rigor of academic research and the reliability of applied fitting procedures.

Realizing the framework’s potential requires coordinated action: common test protocols adopted by manufacturers and research labs, shared datasets for benchmarking and validation, and interdisciplinary collaboration across materials science, biomechanics, aerodynamics, and data science. Empirical studies that implement the framework and report full uncertainty budgets and replicable procedures will be critical to refining predictive models and informing design choices that materially improve player outcomes.

In short,a theoretically grounded,systematically applied framework for equipment performance metrics can bridge the gap between engineering capability and on‑course impact-enabling more precise fitting,faster and better design iteration,and clearer guidance for players and coaches. Ongoing methodological refinement, transparent reporting, and open collaboration will be central to progress in this space.

Precision Golf: How to Measure and Compare Ball Speed, Launch Angle, Spin & MOI

Below are title options grouped by tone. Pick a tone (technical, creative, or SEO) and I’ll refine a headline and meta assets to match.

Title options (pick your tone)

- Technical

- Beyond Feel: A Data-Driven Guide to Ball Speed, Launch, Spin, MOI & Shaft Stiffness

- Engineering Better Swings: Quantifying Launch Angle, Spin, MOI and Shaft Stiffness

- Performance Metrics for Golf Gear: From Ball Speed to Shaft Dynamics

- Creative

- Score with Science: A Playbook for Measuring and Comparing Golf Clubs

- From Launch to Landing: A Data-Driven Framework for Evaluating Golf Clubs

- Decoding Golf Gear: A Practical Framework for Measuring Performance Metrics

- SEO

- Golf Equipment by the Numbers: Standardized Tests for Speed, Spin and Shaft Stiffness

- The metrics of Distance: Standard Tests for Launch, Spin, MOI and Shaft Flex

- Optimize Your Gear: An Analytical Framework for Ball Speed, Spin and Shaft Performance

- Short / Punchy

- Precision Golf: How to Measure and Compare Ball Speed, Launch Angle, Spin & MOI

why standardized testing matters

As golf technology and player data converge, objective measurement becomes the backbone of better fit, better purchase decisions, and better on-course results. Standardized tests remove guesswork, allow apples-to-apples comparisons, and let coaches and fitters optimize clubhead speed, launch angle, spin rate, and shaft behavior for a given golfer’s swing. clear protocols also let manufacturers and self-reliant testers reproduce results reliably.

Key performance metrics and what they meen

Ball speed

Ball speed is the immediate indicator of how efficiently energy transfers from club to ball. Higher ball speed (with a given clubhead speed) typically correlates with more distance. Smash factor – ball speed divided by clubhead speed – is a helpful normalized metric for evaluating how well a club and ball pair translate energy.

Launch angle

Launch angle is the initial trajectory of the ball relative to the ground at impact. Optimal launch angle depends on club type, ball speed, and desired spin rate; drivers generally require higher launch than irons to maximize carry.

Spin rate

Spin rate affects carry, stopping, and roll. Too much backspin on a driver can cost roll; too little can reduce carry.For wedges and approach shots, higher spin improves stopping power. Spin is also the key variable when comparing how different clubheads and grooves interact with a golf ball.

MOI (Moment of Inertia)

MOI measures resistance to twisting on off-center hits. Higher MOI tends to produce more forgiveness and tighter dispersion. MOI can be measured for whole clubs or clubheads and should be considered when comparing drivers and other woods.

Shaft stiffness / flex

Shaft stiffness affects launch,spin,timing and accuracy. Measurements can be reported as flex categories (R, S, X), frequency (Hz), torque (degrees), or bend stiffness curves. A controlled testing framework identifies how shaft profile alters launch conditions and feel for individual swings.

Other useful metrics

- Clubhead speed – the raw rotational/linear speed of the club head.

- Angle of attack – the vertical path of the clubhead at impact; influences launch and spin.

- Spin loft – difference between dynamic loft and angle of attack; a driver’s spin is often tied to its spin loft.

- Carry and total distance – the ultimate yardage outputs, combining launch, spin, and wind/roll.

- Dispersion and curvature – left/right scatter and shot shape consistency.

Tools and test equipment (what to use)

- Launch monitors: Doppler radar (e.g.,TrackMan style),photometric/camera systems (e.g., GCQuad style). Choose a monitor with proven accuracy for ball speed,launch angle and spin rate.

- High-speed cameras for impact and face strike analysis.

- Shaft frequency/torsion testers to measure bend profile, tip stiffness and torque.

- MOI measurement rigs or pendulum setups to quantify head and club MOI.

- Robotic swing systems or mechanical rigs for repeatable strike location and swing parameters when isolating club/shaft variables.

- Climate control and consistent balls (single ball model, same temperature) to minimize environmental noise.

Standardized test protocols (repeatable, rig-friendly)

Use these steps as a baseline protocol for testing clubs and shafts. Keep each variable under tight control so differences reflect gear, not testing noise.

- warm-up: Allow ball and club at stable temperature; run 10 warm-up swings to settle any thermal effects.

- Ball selection: Use a single ball model and batch (same box, same compression) for each set of tests.

- Impact location: Mark a target and ensure consistent strike location; or use a robot for perfect center strikes when isolating clubhead variables.

- Repeatability: Capture a minimum of 10-20 valid shots per configuration; drop highest and lowest outliers for a trimmed-mean result.

- Environmental controls: Indoors preferred; record temperature, humidity, and barometric pressure if outdoors.

- Stable tee & launch conditions: Standardize tee height, ball position, and stance setup (if human testing).

- Metric capture: Record ball speed, clubhead speed, launch angle, spin rate, smash factor, carry, and dispersion for each shot.

| Test | Primary tools | Controlled variables | Outputs |

|---|---|---|---|

| driver ball-speed suite | Radar launch monitor | Same ball, tee height, center strikes | Ball speed, club speed, smash, launch, spin |

| MOI & forgiveness | MOI rig, robot strikes | Same shaft, head orientation, strike location | MOI value, dispersion, average carry |

| Shaft flex & frequency | Frequency analyzer | Same torque test, clamp point | Hz, torque degrees, bend curve |

How to analyze and compare results (practical scoring framework)

A simple, repeatable framework helps translate raw numbers into meaningful conclusions:

- Normalize metrics by clubhead speed (e.g., smash factor) to remove raw power differences.

- Trim outliers and use median or trimmed mean to reduce effect of mis-hits.

- Score by priority: define primary goals (max carry, max forgiveness, low spin) and weight metrics accordingly.

- Consider trade-offs: a lower spin driver may yield more roll but can be harder to control; a stiffer shaft might improve stability for fast swings but reduce feel for slower swings.

- Use dispersion maps: overlay shot plots to see how MOI and shaft changes alter left-right and distance scatter.

Fitting playbook – how to use the tests on real golfers

Combine objective tests with subjective feedback. Here’s a short process to follow in a fitting session:

- Baseline: Capture golfer’s baseline metrics with their current setup (clubhead speed, launch, spin, carry).

- One variable at a time: Change loft, then shaft, then head shape. Isolate variables so you no which change caused which effect.

- Target optimization: Aim for the golfer’s optimal launch/spin window based on clubhead speed and desired flight. Manny launch monitors offer optimizer tools to suggest this window.

- Validate on-course: After lab improvements, test selected setup on-course or in varied conditions to ensure consistent translation.

Benefits and practical tips

- Faster decisions: Objective data speeds up fitting and reduces guesswork when comparing clubs.

- Better buys: A few extra yards from a tailored shaft/loft combo can change club selection and scoring.

- Coach alignment: Data helps coaches prescribe swing changes that align with the golfer’s optimized equipment.

- Practical tips:

- Always warm equipment to playing temperature-ball and shaft response changes with temperature.

- Record environmental conditions and ball model-these can shift spin and carry.

- Document all settings: loft, lie, shaft model, grip size, and adapter positions for repeatability.

Short case study: driver optimization (realistic example)

During a controlled fitting, an amateur player with 95 mph clubhead speed produced:

- Baseline: 137 mph ball speed, 10.8° launch, 3200 rpm spin; average carry 240 yds.

- Intervention: Increased loft by 1° and tried a lower-spin shaft profile.

- result: Ball speed stayed within 1% but launch increased ~0.8°, spin dropped by ~200-300 rpm, and average carry increased several yards while dispersion tightened.

Lesson: small loft and shaft profile changes can shift launch/spin into a more favorable distance window without major swing changes.

Common testing pitfalls to avoid

- Mismatched balls: Testing different ball models across setups will mask real differences.

- Inconsistent strike location: Off-center hits drastically change spin and launch.

- Overfitting to monitor numbers: The goal is better on-course performance; verify lab gains outdoors.

- Ignoring swing consistency: If the golfer is inconsistent, robot testing or a dedicated repeatability protocol helps separate swing noise from equipment effects.

SEO and content tips for testers, brands and writers

Leveraging SEO best practices will help your testing content get found by golfers and fitters:

- Use long-tail keywords naturally: “driver shaft stiffness test,” “launch monitor comparison,” “how to measure spin rate.”

- Structure content with H1/H2/H3 tags (as shown) so search engines and readers can scan quickly.

- Include data tables and labeled images (shot plots,launch monitor screenshots) with descriptive alt text.

- Provide actionable takeaways – readers search for solutions.Make recommendations and link to relevant fitting or purchase pages.

- Keep meta title under ~60 characters and meta description under ~160 characters (see the top of this article for an example).

Next steps – choose a tone & headline

Tell me which tone you prefer (technical, creative, or SEO) and which title from the lists above you like best. I’ll refine the selected headline, meta title/description, URL slug, and provide a short social share blurb optimized for clicks. If you want, I can also adapt the article into a magazine-style feature, a short blog post, or a checklist for fitters.