advances in sensor technology, computational modeling, and data‑driven analytics have opened powerful new pathways to describe and improve the tightly coordinated sequence of actions that produce a golf swing. This rewritten article outlines a practical, research‑informed toolkit that connects biomechanical theory to measurable performance – combining multisegment kinematic and kinetic models, modern motion‑capture workflows, and statistical / machine‑learning methods. The focus is on clarifying how joint coordination and kinetic‑chain energy transfer shape clubhead behavior and launch outcomes,while simultaneously supporting greater efficiency and lower injury exposure.

Methodological coverage spans inverse dynamics and subject‑specific musculoskeletal simulation, dimensionality‑reduction and functional data techniques, optimization‑based movement synthesis, and both supervised and unsupervised learning for pattern revelation and timely feedback. Core evaluation criteria include mechanical efficiency (segmental work and power flow), robustness to within‑ and between‑trial variability, repeatability of phase‑defining events, and how sensitive launch conditions are to targeted kinematic changes. Practical validation topics - sensor fusion, calibration routines, and cross‑validation on ecologically valid swings across ability levels – are emphasized. The workflow proposed for researchers and coaches is: (1) choose a hypothesis‑aligned model, (2) collect and preprocess high‑quality data, (3) extract informative features and reduce dimensionality, (4) apply predictive/prescriptive analytics linking mechanics to outcomes, and (5) close the loop with individualized feedback for training and rehab. Integrating mechanistic models with scalable analytics yields objective assessment tools, focused coaching prescriptions, and iterative betterment of technique and training systems.Note: the web search results returned with the original submission were unrelated to golf biomechanics; the material below is self-contained and devoted to biomechanical and data‑analytic considerations.

Foundations: Mechanical and Control Models for the Golf Swing

Modern modeling strategies for the golf swing combine rigid‑body dynamics, continuum/soft‑tissue concepts, and models of neuromuscular control.These approaches rest on explicit assumptions about how the body is segmented, which joint constraints apply, and how soft tissues behave; those assumptions determine which mechanical invariants (for example, conservation of angular momentum about the body center) will be enforced and at what spatial or temporal scales energy transfer, torque generation, and stability are analyzed. Stated differently, the chosen model formalizes what aspects of the swing are emphasized and which are approximated.

Technically, models are expressed using coordinate frames and generalized coordinates and can be solved either in forward (simulation) or inverse (data‑driven estimation) dynamics modes. Optimization appears naturally as a mechanism to encode performance aims – maximize clubhead velocity, reduce lateral forces, or limit variability for accuracy – by defining cost functions and constraints. A clear distinction must be kept between models used for hypothesis generation and those intended for empirical testing: model predictions shoudl be falsifiable through measurement and not simply descriptive restatements of observed data.

Selecting and simplifying models is a deliberate trade‑off between realism and tractability.typical modeling paradigms include:

- Segmental multibody: treat limbs and torso as rigid links with joint torques – computationally efficient for inverse‑dynamics and trajectory work.

- Musculoskeletal: include muscle actuators (e.g., Hill‑type elements) to estimate activations, metabolic cost, and fatigue effects.

- Continuum/soft‑tissue: model local deformations and contact (helpful for grip mechanics and impact detail).

- Stochastic modules: incorporate noise models for motor variability and sensory error to predict dispersion and robustness.

Validation is integral: sensitivity and identifiability analyses,together with cross‑validation against motion capture and force‑platform recordings,establish a model’s predictive value. The short table that follows condenses common trade‑offs across modeling choices:

| Model class | Primary Strength | Typical Use |

|---|---|---|

| Segmental multibody | Computational speed | Inverse dynamics, trajectory analysis |

| Musculoskeletal | Physiological realism | Activation patterns, fatigue modeling |

| Continuum / FE | local stress / strain detail | Grip mechanics, impact zones |

Measurement Technologies: Choosing and Combining Capture Modalities

Quantitative swing analysis now leverages a range of capture systems: optical marker‑based arrays, markerless video/depth solutions, and inertial measurement units (IMUs). Each technology is grounded in different measurement physics and has distinct practical implications. choose the sensing modality based on your question: optical systems deliver high‑precision 3D kinematics in a calibrated volume; markerless solutions enable in‑field or on‑course testing with little setup; IMUs provide temporally dense rotational and linear signals suited to longitudinal monitoring. In practice, hybrid sensor fusion (e.g., optical spatial fidelity combined with IMU temporal resolution) often yields the most complete kinematic and kinetic picture.

Reproducible capture requires disciplined protocols: consistent marker placements or anatomical reference definitions, multi‑camera calibration with low residual error, synchronized time bases (hardware triggers where possible), and controlled environmental conditions. the sampling regimes below summarize typical trade‑offs for applied research and coaching:

| Sensor | Typical rate | Strength | Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Optical (marker) | 200-1000 Hz | High spatial accuracy | Lab‑constrained, marker occlusion |

| Markerless (video/depth) | 60-240 Hz | Field‑friendly, minimal prep | Lower 3D precision, model bias |

| IMU | 100-2000 Hz | Excellent temporal fidelity | Drift, alignment to segments |

Data pipelines must formalize synchronization, denoising, and biomechanical mapping so raw sensor streams become actionable variables. Typical steps include hardware synchronization, appropriate filtering (e.g., Butterworth filters with cutoffs chosen from residual analysis), anatomical coordinate transformations, and inverse kinematics or optimization‑based fitting to estimate joint centers and segment orientations. Reliability checks – residual analyses,marker dropout sensitivity,and cross‑validation against reference trials – protect computed metrics such as segment angular velocities,timing of the kinematic sequence,and clubhead speed at impact.

For coach‑facing outputs, quantify uncertainty and prioritize robust, validated metrics. Recommended practice is to report standard errors or confidence intervals for primary metrics, separate real‑time indicators (for example peak wrist angular velocity from an IMU) from offline diagnostics (e.g., intersegment energy transfer indices), and use standardized visualizations for longitudinal monitoring.Machine‑learning classifiers or clustering can reveal atypical swing types, but these tools must be cross‑validated and feature provenance clearly explained so results remain interpretable and useful.

Mechanical Signatures: Sequencing, Forces, and Launch Control

Efficient energy transfer is primarily expressed in the timing and magnitude of segmental rotations – commonly called the kinematic sequence. A pelvis‑first rotation that precedes torso rotation (the proximal‑to‑distal pattern) generates increasing angular velocities along the chain and reduces intersegmental dissipation. High‑speed capture and IMUs can detect the timing and size of peak angular velocities at the hips, trunk and shoulders; these inter‑segment timing offsets often distinguish efficient from inefficient swings as clearly as raw peak speeds do.

From a kinetic standpoint,ground reaction force (GRF) patterns,joint moments,and axial torques provide the force basis for the kinematic chain. Examining force vectors shows how well an athlete converts lower‑limb ground interaction into rotational impulse. as an example, a rapid mediolateral impulse followed by progressive axial loading is characteristic of powerful trunk acceleration. Important kinetic markers include:

- Peak vertical and horizontal GRF – indicates capacity to create and redirect force.

- Hip and knee extension moments – reflect transmission of leg drive into trunk rotation.

- Trunk rotational power – combines torque and angular velocity to estimate energy available to the club.

For routine coaching and monitoring, concise markers and target criteria are most practical. The table below lists exemplar metrics, measurement approaches, and pragmatic target guidance. Treat thresholds as individualized benchmarks rather than universal norms: relative gains and consistency over time usually predict better ball control than one‑off peaks.

| Marker | measurement | Representative Target |

|---|---|---|

| X‑factor (torso‑pelvis separation) | Angular difference at top of backswing (motion capture) | Ample torsion at top; controlled unwind on downswing |

| Peak GRF | Force plate peak vertical & lateral impulses | Marked impulse timed before transition |

| Clubhead speed consistency | Radar / motion capture repeatability | Low within‑session SD; individualized target |

Converting biomechanical markers into launch outcomes requires aligning mechanical states around impact with launch parameters (speed, launch angle, spin) and their variability. Temporal synchronization of torque peaks, GRF impulses, and clubhead acceleration relative to impact tends to predict reduced dispersion in launch metrics. Data‑driven feedback loops that couple motion capture markers with launch monitors enable targeted interventions – timing drills, strength/power programming, and technical cues – and objective tracking of transfer: improved synchronization and repeatability typically decrease lateral dispersion and narrow spin‑launch envelopes.

From Mechanics to Health: Musculoskeletal Modeling and Injury Prevention

High‑resolution pipelines increasingly pair subject‑specific musculoskeletal models with measured swing kinematics to estimate internal loads not directly visible from video alone. When EMG‑informed muscle estimates, inverse dynamics, and forward simulations are combined, net joint moments can be partitioned into muscle and tissue loads, producing estimates of tendon strain, ligament stress, and joint compression. Those quantities make the link between swing mechanics and clinical presentations of pain or dysfunction.

Risk modeling translates mechanical exposures into probabilistic injury scores by considering tissue capacity, fatigue accumulation, and peak loading rates. Methods include cumulative‑load time‑to‑failure models, Bayesian models of tissue tolerance variability, and machine‑learning classifiers trained to spot movement patterns associated with injury. Integration with clinical care pathways supports translating these modeled exposures into personalized prevention strategies and rehabilitation plans.

model‑guided prevention emphasizes both reducing harmful exposures and bolstering tissue capacity. Common intervention domains identified by quantitative modeling include:

- Technique modification – alter sequencing or reduce peak trunk rotation velocity to lower lumbar shear.

- Strength and conditioning – build eccentric hip and trunk capacity to tolerate transverse loads.

- Load management – control swing volume and progression according to cumulative‑load profiles.

- equipment tuning – shaft stiffness and grip choices that influence clubhead dynamics and distal loading.

- Monitoring and recovery – sensor‑based workload tracking and staged recovery protocols to avoid overuse.

These priorities are rank‑ordered by modeled risk contribution so practitioners can focus limited training time on changes with the largest expected injury‑reduction benefits.

To support practical adoption, model outputs can be mapped into concise risk‑to‑action tables that clinicians and coaches can use in athlete management systems or electronic medical records. The sample table below demonstrates how modeled metrics translate to recommended actions:

| Modeled Metric | Typical Threshold | Recommended Action |

|---|---|---|

| Peak lumbar shear | > 3.5× bodyweight | Technique cueing; reduce rotation velocity |

| Accumulated tendon load | Steep weekly slope | Reduce practice volume; eccentric strengthening |

| Shoulder external rotation strain | Repeated peaks above normative 95th pct. | Mobility work + taper; equipment check |

When combined, musculoskeletal simulation, wearable monitoring and probabilistic risk models enable individualized prevention plans that protect performance while reducing injury risk. Effective implementation depends on cross‑disciplinary collaboration among biomechanists, clinicians, coaches and data scientists to validate model outputs against clinical outcomes and to refine intervention thresholds across diverse golfer populations.

Real‑Time Systems: Low‑Latency Feedback Architectures for Coaching

Contemporary coaching platforms bring together wearables and optical capture into layered pipelines that prioritize low latency and robust fusion. architectures commonly separate sensor capture, preprocessing, real‑time inference, and feedback rendering, with each layer constrained by timing and reliability budgets. Sensor fusion reconciles inertial,pressure and markerless pose streams to produce a single biomechanical state vector (joint angles,clubhead kinematics,center‑of‑pressure). Hard real‑time constraints typically force trade‑offs between model complexity and closed‑loop latencies (sub‑100 ms is a common practical target to preserve perceptual contiguity between action and cue).

Feedback modalities are chosen to maximize learning while avoiding cognitive overload. Effective systems synchronize multimodal cues to meaningful swing events (e.g., backswing top, transition, impact). Typical modalities include:

- Haptic – vibrotactile pulses that encode timing errors or weight‑shift magnitude;

- Auditory – sonified metrics indicating tempo and deviations from target;

- Visual – minimal overlays or glyphs showing alignment and swing plane;

- Prioritized coaching cues – short, ranked instructions derived from an error list.

Personalization is achieved by adapting model priors online and selecting coachable metrics tailored to an athlete’s anthropometry and mobility. Transfer learning and Bayesian updating enable population models to be rapidly specialized to an individual, improving both accuracy and interpretability of feedback. Calibration routines during warm‑ups correct sensor drift and re‑estimate limb lengths; hierarchical reinforcement learning can be used offline to optimize feedback policies that yield measurable gains across training sessions. Interpretability is a central design goal so feedback is actionable for both elite and recreational players.

Operational evaluation focuses on a compact set of real‑time metrics: latency, false positive rate, feedback utility (immediate corrective effect), and athlete acceptance. Example sensor specifications from field evaluations are shown below; coach interfaces typically combine trend dashboards with event‑level playback to support synchronous or asynchronous instruction while maintaining the temporal fidelity necessary for motor learning.

| Sensor | Sampling | Typical Latency |

|---|---|---|

| IMU (wrist/torso) | 200-1000 Hz | 10-30 ms |

| Markerless camera | 60-240 fps | 30-70 ms |

| Pressure mat | 50-200 Hz | 10-40 ms |

Algorithms: Machine‑Learning Architectures for Individualized Improvement

conceiving algorithmic systems as engineered subsystems clarifies their role in augmenting human coaching: they are tools that apply data and computation to achieve a defined task (improving swing mechanics).Treating models as engineered artifacts-subject to specification, modularity, and validation-encourages the deliberate integration of biomechanical priors, sensor constraints, and coach heuristics into model design, increasing interpretability and repeatability.

Algorithm choice should be driven by the personalization goal and available data. Typical model families include:

- Supervised learning: regressors and ensemble methods for mapping pose/time‑series features to launch outcomes and face orientation.

- Sequence models: rnns,temporal CNNs and Transformers to capture temporal coordination and phase transitions.

- Reinforcement learning: policy optimization to suggest incremental motor adjustments in simulation or constrained practice.

- Probabilistic/bayesian models: for principled uncertainty quantification and individualized confidence bounds.

- Transfer & federated learning: share population knowledge while preserving privacy and enabling fast personalization.

Personalization pipelines fuse multimodal inputs, extract salient biomechanical features, and adapt model parameters to an athlete’s morphology and motor fingerprint. Important components include sensor calibration,normalization into body‑centric coordinates,and online adaptation layers that learn residuals from an athlete’s baseline. The compact mapping below illustrates common input→model→output relationships used in practice:

| Input Modality | Model Type | Personalized Output |

|---|---|---|

| IMU & motion capture | Temporal CNN + Kalman filter | Segment timing corrections (ms) |

| Video kinematics | Pose Transformer | Club path & face angle adjustments |

| Ball flight data | Ensemble regression | launch parameter targets |

production deployment requires continuous validation, explainability, and operational monitoring. Pair standard predictive metrics (RMSE, MAE) with domain measures (carry error, dispersion angle) and uncertainty estimates. Constrain model complexity to operational budgets (latency, battery, connectivity); distilled edge models are often preferable for live coaching. Maintain human‑in‑the‑loop checks: provide confidence‑weighted, actionable recommendations to coaches and players and keep an audit trail for data provenance and model updates to support governance and ethical use.

Turning Analytics into Practice: Coaching Protocols and Intervention Design

Analytics only matter if they convert into clear, repeatable coaching actions. That requires operational metrics (for example peak pelvis rotation velocity, kinematic‑sequence timing, inter‑limb asymmetry) and decision rules that map deviations into targeted interventions. Interdisciplinary validation – involving coaches, biomechanists and strength & conditioning specialists – ensures prescriptions are physiologically plausible and technically coherent. Maintain intervention fidelity, standardized testing protocols, and documentation so outcomes are comparable across athletes and over time.

Choose interventions from evidence‑based families matched to the limiting mechanism identified by analytics. Common categories include:

- Mobility & motor control: rotation drills, thoracic mobility progressions, and dynamic stability work to support a functional X‑factor.

- Strength & power conditioning: hip extension and rotational power programs,eccentric control training,and force‑vector specific lifts informed by GRF asymmetries.

- Timing & sequencing retraining: constraint‑led skill drills, tempo/rythm practice, and phased re‑timing using metronome or percussion cues.

- Augmented feedback: real‑time clubhead‑speed cues, video overlays of target sequences, and post‑trial summary metrics to accelerate motor learning.

Practical decision‑making benefits from short reference tables and clear progression rules. The example table below maps common analytic findings to prioritized interventions and a short progression rule. Coaches should use single‑subject experimental designs (e.g., AB designs or multiple baselines) and retention/transfer testing to verify that changes are durable and transfer to on‑course play.

| Metric | Threshold | Recommended Intervention |

|---|---|---|

| Pelvis rotation velocity | <10% vs cohort | rotational power drills + band‑resisted swings |

| Kinematic sequence lag | >50 ms delayed | Sequencing tempo drills with augmented audio cues |

| Medial‑lateral GRF asymmetry | >12% difference | Single‑leg stability + force‑bias strength work |

Implementation must be athlete‑centred and pragmatic: each session should translate analytics into a short plan with prioritized targets, measurable micro‑goals and feedback modalities matched to the learner. Coaches should track progress via a compact dashboard (weekly metric changes,adherence,perceived exertion) and apply progression criteria (for example 5-10% metric improvement or demonstrated retention at one week) before increasing task complexity. Embed athlete education and self‑monitoring (simple biofeedback signals and home drills) to help laboratory gains transfer to on‑course performance and longer‑term motor behavior change.

Q&A

Note: Search results returned with the original submission were not relevant to golf biomechanics.The Q&A below summarizes standard practices and evidence‑based recommendations from biomechanics, motion analysis and data‑science applied to golf swing optimization.

Q1. What is an “analytical framework” for optimizing golf‑swing mechanics?

A1. An analytical framework is a reproducible pipeline that ties theoretical models, sensing choices, signal processing, statistical/computational analyses and feedback strategies into a coherent process for measuring, explaining and improving the golf swing. It defines the biomechanical model (e.g., rigid‑body, musculoskeletal), sensing modalities (optical capture, IMUs, force plates, launch monitors), preprocessing steps (filtering, segmentation), feature extraction, predictive/prescriptive modeling, and how outputs translate into coaching actions.

Q2. What are the main biomechanical objectives when optimizing a swing?

A2. Objectives typically include: improving performance outcomes (clubhead and ball speed, accuracy, desirable launch/spin), increasing mechanical efficiency (optimal sequencing and energy transfer), reducing variability (greater consistency), and minimizing injury risk by keeping internal loads within safe ranges. these aims are often balanced as trade‑offs (greater power vs. higher injury exposure).

Q3.which biomechanical models suit swing analysis?

A3. Common choices:

– Rigid‑body multisegment models: effective for kinematics and inverse dynamics joint moments.

– Musculoskeletal models: needed to estimate muscle forces, activations and fatigue (e.g., opensim).- hybrid approaches: combine multibody dynamics with deformable contact for grip and impact detail.

Model selection depends on the question – joint moments vs. muscle/tissue loading vs. impact mechanics.

Q4. Which sensors are recommended?

A4. High‑accuracy tools:

– Optical marker systems (Vicon, Qualisys) for gold‑standard kinematics.

– Force plates for GRF and center‑of‑pressure.

– Launch monitors (TrackMan, FlightScope etc.) for ball speed, launch angle and spin.

– Wearable IMUs for field monitoring.- Markerless video tools (OpenPose, DeepLabCut) for scalable deployment.

Sensor fusion (IMUs + video + launch monitor) frequently enough gives the best compromise between accuracy and ecological validity.

Q5. What key kinematic and kinetic metrics should be extracted?

A5. Kinematics: clubhead speed, clubface orientation at impact, club path, shaft lean, swing plane, joint angles (hip, trunk, shoulder, elbow), angular velocities/accelerations, and kinematic‑sequence timing. Kinetics: GRFs and impulses, joint moments and powers, estimated muscle forces, and intersegment energy transfer. Ball metrics: ball speed, launch angle, spin, carry, and dispersion.

Q6. How should swing data be preprocessed and segmented?

A6. Recommended pipeline:

– Synchronize devices and resample to a common frequency.

– Apply biomechanically justified filtering (residual analysis).

– Transform to anatomical and club coordinate systems.

– Detect events (address, top, impact, follow‑through) using kinematic/kinetic thresholds.

– Normalize time (percentage of swing) for averaging and comparison.

Q7. Which statistical and machine‑learning methods are useful?

A7. Useful tools:

– Mixed‑effects and inferential statistics for repeated measures.

– Time‑series and functional data analysis, dynamic time warping.

– Dimensionality reduction (PCA, SVD) to identify dominant modes.

– Supervised models (regression, ensemble trees, neural nets) to predict outcomes.

– Unsupervised clustering to identify swing archetypes.

– Explainability techniques (SHAP, feature importance) for coach interpretability.

Q8.How is the kinematic sequence quantified?

A8. Measure segment angular velocities across time, identify peak times and magnitudes for pelvis → thorax → arms → club, compute intersegment timing lags and magnitude ratios, and use cross‑correlation or phase metrics to assess coupling. Relate sequence metrics to outcomes (clubhead speed,dispersion) via regression or mediation analyses.

Q9. What optimization strategies apply to improving mechanics?

A9. Strategies include:

– Constrained deterministic optimization (maximize ball speed subject to physiological limits).

– Heuristic/global methods (genetic algorithms, particle swarm) for nonconvex landscapes.

- Bayesian optimization for expensive evaluations.

– Multi‑objective Pareto analysis to balance power, accuracy and safety.- Sensitivity and uncertainty analyses to prioritize influential parameters.

Q10. How is model validation performed?

A10. Steps:

– Kinematic checks against autonomous measures (high‑speed video, marker data).

– Kinetic validation where instrumented measures exist (force plates).

– Predictive validation with cross‑validation/holdout datasets and metrics (RMSE, MAE, R^2).

– External validation via intervention studies measuring performance and injury outcomes.

Q11. how can data‑driven feedback be delivered?

A11. Deliver via:

– Real‑time cues (auditory, haptic, simple visual overlays) for immediate correction.

– Near‑real‑time session summaries (key metrics, trends).

– Longitudinal dashboards for session‑to‑session tracking.

– Translate numeric outputs into short, coachable instructions to avoid overload.

Q12. How should individual variability be handled?

A12. Use individualized baselines and body‑normalized metrics,cluster players by archetype,employ mixed‑effects models to partition variance,and run subject‑specific simulations when prescribing interventions.

Q13. Common pitfalls and limits?

A13. Watch for measurement error and soft‑tissue artifact, limited ecological validity of lab protocols, overfitting without sufficient data, challenges in causal inference from observational data, computational cost of high‑fidelity simulations, and ethical/privacy issues around athlete data.

Q14. How to integrate injury risk?

A14. Estimate internal joint loads via inverse dynamics/musculoskeletal models, set safety thresholds with clinician input, include load limits in optimization objectives, monitor acute‑to‑chronic workload ratios, and use longitudinal screening tied to clinical oversight.

Q15. recommended experimental designs for intervention studies?

A15.Aim for adequate sample sizes (power analysis), randomized or crossover designs where feasible, within‑subject repeated measures, pre‑registration of hypotheses, blinded outcome assessment where possible, and longitudinal follow‑up for retention and injury outcomes.Use mixed‑effects models for analysis.

Q16. Role of machine learning in swing analysis?

A16. ML can predict performance outcomes from high‑dimensional inputs, detect faults automatically, and discover latent archetypes. Ensure interpretability, guard against confounds (e.g., player identity leakage), and enforce proper cross‑validation and feature governance.Q17. How to communicate results to practitioners?

A17. Provide 2-3 prioritized session objectives, visuals comparing before/after or target trajectories, drill protocols with measurable checkpoints, estimated effect sizes and confidence bounds, and any safety warnings.

Q18. Future directions for analytical frameworks?

A18. Trends include markerless and wearable fusion for field monitoring, low‑latency closed‑loop feedback, integrating physiological signals (EMG, muscle oxygenation), explainable AI for obvious decisions, and large datasets to enable normative models and transfer learning.

Q19.What ethical and governance issues apply?

A19. Key points: informed consent, purpose limitation, secure storage of biomechanical and health data, transparent data‑use policies for commercial products or data sharing, preventing misuse (e.g., unfair selection) and algorithmic bias, and compliance with applicable data‑protection laws.

Q20. What is a practical minimal pipeline a coach or researcher can use immediately?

A20.Minimal pipeline:

– Hardware: IMUs or high‑speed video plus a launch monitor.

– Protocol: standardized warm‑up and a consistent set of swings (10-20) with fixed club/ball.- Processing: synchronize,low‑pass filter,detect top/impact,normalize swing time.

– Extract: clubhead speed, face angle at impact, peak trunk rotation velocity, and GRF surrogates if available.

- Analysis: compute session means and within‑session variability, compare to baseline.

– Feedback: give one to two concise metrics with a simple drill; reassess after the prescribed practice block.

If preferred, supplementary material can be prepared: a coach‑focused Q&A, a technical appendix with sample inverse‑dynamics equations and optimization objectives, or a study protocol template with power calculations and an analysis script outline.

integrated analytical frameworks – spanning biomechanical modeling, motion capture analytics and data‑driven feedback – deliver a rigorous foundation for understanding and improving golf‑swing mechanics. by fusing multiscale mechanical models with high‑quality kinematic and kinetic measurement and by leveraging modern data science,practitioners and researchers can more precisely map relationships among efficiency,power generation and shot accuracy,and translate laboratory insights into individualized coaching and training interventions.

three practical takeaways: first, approach swing optimization as a model‑informed, individualized process that respects an athlete’s morphology and motor control constraints. Second, seek convergent evidence from complementary modalities (marker‑based capture, wearables, force measures and launch monitors) and from longitudinal testing to link mechanics to on‑course results. Third, define “optimal” explicitly for your context (performance vs. health) and use multi‑objective decision frameworks to manage trade‑offs.

Limitations remain: measurement error, ecological validity concerns, and inter‑individual variability limit universal prescriptions. Ongoing advances will benefit from standardized outcomes, open validation datasets, and interdisciplinary collaboration across biomechanics, motor control, data science and applied coaching. Emerging tools – real‑time machine‑learning feedback, validated wearable sensors and improved musculoskeletal models – promise to close the loop between measurement, prescription and performance adaptation.

Remember: “optimal” is context dependent. Achieving optimal swing mechanics requires explicit success criteria, rigorous measurement and iterative, evidence‑based interventions. Continued empirical work and practitioner-researcher partnerships are essential to convert these analytical frameworks into measurable, on‑course improvement.

Pick a Title & Style: Data-Driven Golf Swing Frameworks for Every Golfer

Here are ten engaging title options. Pick a style (technical, coaching, or catchy) and I can refine one to match your audience-club pros, tech-minded players, or casual golfers.

- Unlocking the Perfect Swing: Data-Driven Frameworks for Golfers

- The Science of the Swing: Biomechanics and Analytics to Maximize distance and Accuracy

- Swing smarter: Analytical Tools to Optimize Power,Precision,and Consistency

- From Motion Capture to Mastery: A Modern Framework for Golf Swing Optimization

- Precision Swing: Harnessing Biomechanics and Data to Improve Your Game

- The Analytics-Backed Path to a better Golf Swing

- Golf Swing Engineering: A Data-Driven Blueprint for Power and Control

- Mastering the Swing: Integrating Biomechanics,motion capture,and Analytics

- High-Performance Swing: Scientific Methods to Boost efficiency and Accuracy

- Biomechanics to Birdies: Analytical Frameworks for Swing Success

Which Style Should You Choose?

Each title fits a slightly different editorial voice and audience. Use the table below to help select the best option for your content goals.

| Title | Style | Best Audience |

|---|---|---|

| Unlocking the Perfect Swing: Data-Driven Frameworks for Golfers | Coaching | Club pros, instructors |

| The Science of the Swing: Biomechanics and Analytics to Maximize Distance and Accuracy | Technical | Tech-minded players, researchers |

| Swing Smarter: Analytical Tools to Optimize Power, Precision, and Consistency | Catchy / Practical | casual and performance-oriented golfers |

| from Motion Capture to Mastery: A Modern framework for Golf Swing Optimization | Technical / Narrative | Coaches, facilities with launch monitors |

how to Tailor a Title: Speedy Guide

- Club pros / Instructors: Use authoritative coaching language, emphasize repeatability and drills (e.g., “Unlocking the Perfect Swing: Data-Driven Frameworks for Golfers”).

- Tech-minded players: Highlight tools and metrics (e.g., “The Science of the Swing: Biomechanics and Analytics…”).

- Casual golfers: Keep it concise, benefits-first, and approachable (e.g., “Swing Smarter: Analytical Tools to Optimize…”).

Core Components of a Data-Driven Golf Swing Framework

To craft an effective, analytics-backed golf swing program, integrate these pillars into your coaching or practice:

1. measurement: Capture the right metrics

- Clubhead speed, ball speed, and smash factor - primary distance indicators

- Launch angle and spin rate – determine carry, rollout, and trajectory

- Face angle and club path (face-to-path) – primary accuracy drivers

- Kinematic sequence and X-factor (shoulder-hip separation) - efficiency and power generation

- Ground reaction forces and weight shift – lower-body contribution to torque and stability

2. Tools: From launch monitors to markerless motion capture

Use a mix of tools depending on budget and goals:

- Launch monitors (TrackMan, FlightScope, GCQuad) - ball-flight and club metrics

- High-speed video (240-1000 fps) – face awareness and impact position analysis

- Motion capture (optical marker-based or markerless) – joint kinematics, sequencing and plane tracking

- Wearables (IMUs, Blast Motion, Arccos sensors) – practice-pleasant data and tempo tracking

3. Analysis: Turn raw numbers into decisions

- Prioritize a few KPIs per player: e.g., for a driver-focused plan - clubhead speed, launch angle, spin rate, and face-to-path.

- Look for patterns across launch and body metrics – a closed face with out-to-in path often yields hooks.

- Use video + data overlay to communicate a single corrective cue at a time.

Actionable Drills & Training Blocks (Practical Tips)

Below are coach-friendly drills that pair with key metrics. These are useful whether you coach full-time or just want better results on the range.

Tempo & Timing

- Metronome Drill – set a 3:1 backswing-to-downswing rhythm and record with a wearable to measure consistency.

- pause-at-Top drill - helps sync lower body initiation; watch for improved sequencing and better clubface control.

Power & Kinematic Sequence

- Step Drill – step toward the target during transition to promote correct weight shift and increase ground reaction force.

- Hip-Lead Drill – focus on initiating downswing with hips, not arms; measure clubhead speed before and after.

Impact & Face Control

- Impact Bag Drill – improve hand position and compressive impact feel; track ball speed gains.

- Face Awareness Drill – slow-motion swings to rehearse face-square at impact; use video to confirm face angle.

Sample 6-Week Data-Driven Training Plan

Weekly focus, simple metrics, and drills to deliver measurable improvement in distance and accuracy.

| Week | Focus | Key Metric | Drills |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Baseline & setup | Clubhead speed, launch/face | Full-swing video, launch monitor baseline |

| 2 | Tempo & timing | Tempo consistency | Metronome, pause-at-top |

| 3 | Lower-body sequencing | Hip speed / GRF | Step drill, hip-lead |

| 4 | Impact & compression | Ball speed, smash factor | Impact bag, forward shaft lean |

| 5 | Accuracy & shot shape | Face-to-path, dispersion | Alignment sticks, path drills |

| 6 | Integration & validation | Overall carry distance & dispersion | Simulated course, pressure reps |

Metrics to Track – and Why Thay Matter

Focus on these metrics regularly; they give a clear signal of improvement and help prioritize interventions.

- Clubhead speed: Direct driver distance correlate – improve with sequencing and rotational power.

- Ball speed: Efficiency of energy transfer – track smash factor (ball speed / clubhead speed).

- Launch angle & spin rate: Optimal combination yields maximum carry and controllable rollout.

- Face angle & path: Small degrees of face misalignment dramatically alter dispersion.

- Vertical ground reaction force (vGRF): Greater downward and lateral push-off produces higher clubhead speed when timed correctly.

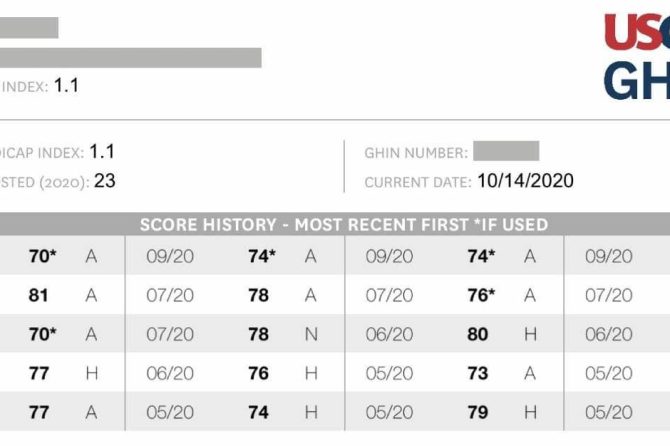

case Study: Hypothetical Example (Club Pro)

Coach A used motion capture + launch monitor to diagnose a student who was losing distance and struggling with pockets of slice. Baseline assessment revealed:

- Clubhead speed: 97 mph

- Ball speed: 136 mph (smash factor 1.40)

- Face-to-path: +2° (open face relative to path)

- Late hip rotation causing open face at impact

Intervention:

- Weeks 1-2: Tempo drills and pausing at the top to re-time downswing initiation

- Weeks 3-4: Hip-lead and step drills to correct sequencing

- Weeks 5-6: Impact-focused drills and pressure reps

Results after 6 weeks (hypothetical): clubhead speed up to 100 mph, smash factor to 1.45, face-to-path near 0°, and tighter dispersion – demonstrating how measurements plus simple interventions create repeatable gains.

Tailored Messaging: Title variants for Each Audience

For Club Pros & instructors

Recommended title: “unlocking the Perfect Swing: Data-Driven Frameworks for Golfers”

- Emphasize repeatability, coaching communication, and drills validated by measurable change.

- Include downloadable session plans, video overlays, and KPI sheets for students.

For Tech-Minded Players

Recommended title: “The Science of the Swing: Biomechanics and Analytics to Maximize Distance and Accuracy”

- Deep dive into launch monitor outputs, kinematic sequencing graphs, and markerless motion capture use-cases.

- Provide tool comparisons (launch monitors vs. wearables) and data-interpretation tips.

For Casual Golfers

recommended title: “Swing Smarter: Analytical Tools to Optimize Power, Precision, and Consistency”

- Keep language simple, focus on 2-3 practical drills, and emphasize quick wins (tempo, posture, impact).

- Suggest affordable tech options like smartphone slow-motion video or inexpensive sensors.

SEO & Content Tips for Publishing This Article

- Use primary keyword phrases: “golf swing,” “biomechanics,” “motion capture,” and “launch monitor” in headings and naturally throughout copy.

- Include long-tail keywords in subheadings, such as “data-driven golf swing framework,” “how to increase clubhead speed,” and “drills to improve impact.”

- Optimize images with alt text: e.g., “motion-capture golf swing analysis” and “driver launch monitor screen.”

- Add internal links to related posts: “driver fitting,” “short game analytics,” and “tempo drills.”

- Offer downloadable assets: practice plan PDF, KPI tracking sheet-these increase dwell time and conversions.

Next Steps – pick a Title and Target Audience

Tell me which style you want (technical, coaching, or catchy) and the audience (club pro, tech-minded player, casual golfer). I’ll refine one of the titles into an SEO-optimized H1 and write a customized opening section, meta tags, and a 500-800 word landing page or blog post tailored to that audience.

Want me to refine one of the titles now? Pick a title and a style and I’ll produce a tailored version complete with suggested featured image alt text, H1/H2 structure, and on-page SEO recommendations.