the golf swing is a highly coordinated, multi-segment movement shaped by the interplay of anatomical constraints, nervous‑system control, and the mechanical properties of clubs and balls. Treating the swing as an analyzable system makes it possible to break it into measurable components-motion patterns, force generation, energy transfer, and timing-and to relate those components to practical outcomes such as clubhead velocity, shot dispersion, and repeatability. integrating ideas from classical mechanics, motor‑learning science, and modern computational modelling, the following text blends cross‑disciplinary knowledge to explain how mechanical processes drive skill progress, explain performance differences, and influence injury susceptibility across skill levels.

Advances in measurement-high‑speed optical capture, wearable inertial sensors, force platforms, and machine‑learning analysis-have widened our ability to quantify swing mechanics and test causal ideas. This review compares dominant analytical approaches (for exmaple, segmental coordination models, kinetic‑chain frameworks, inverse dynamics, and optimization simulations), highlights their relative strengths and limitations, and draws out practical lessons for coaching and equipment fitting. Special attention is given to bringing laboratory precision into on‑course contexts, acknowledging measurement challenges, and suggesting future research that marries high‑fidelity sensing with hypothesis‑driven models to enhance both performance and injury mitigation.

Note: supplied automated search results did not provide domain‑specific literature on golf biomechanics; the material below is synthesized from established scientific principles and current practice.

Segmental Timing and Motion Analysis: Practical Insights and Targeted Training

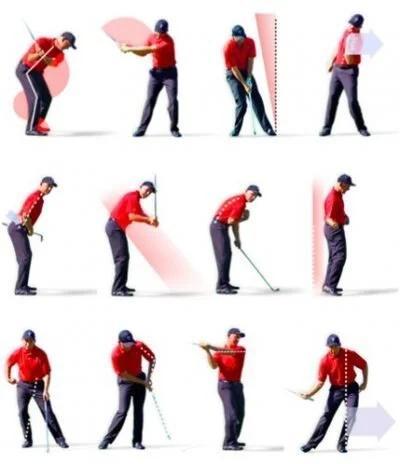

Detailed kinematic assessment reveals the temporal chain that underlies ball speed and directional control. Using high‑frame‑rate optical systems and IMUs, analysts quantify the proximal‑to‑distal order of motion, peak angular velocities of each body segment, and the sequencing of events such as pelvis rotation start, maximum shoulder turn, and greatest clubhead speed. extracting these discrete timestamps and velocity profiles allows verification of the desired kinetic chain (hips → trunk → arms → club) and measurement of features like peak angular velocity magnitudes and trunk‑pelvis separation (the so‑called X‑factor) - metrics that are tightly linked with power output and consistency.

when sequencing departs from the ideal, predictable declines in performance and increased injury risk follow. Typical faulty patterns observed in datasets include premature arm acceleration (which steals energy from proximal segments), reversed timing where distal peaks precede proximal ones, and underutilization of the pelvis. Practical markers to monitor during analysis include:

- Latency between backswing completion and pelvic rotation onset

- Delay from pelvic peak to peak shoulder angular velocity

- Timing and magnitude of wrist-**** release

- Relative timing between trunk lateral bend and arm extension

Measuring these variables makes it possible to separate timing faults from magnitude deficits and to prescribe precise corrective work.

Rehabilitation and coaching should convert kinematic findings into drills that restore correct timing and intersegmental coupling.Emphasis should be placed on rehearsing the temporal sequence, not merely increasing strength or mobility. Useful interventions include resisted rotational patterns to promote delayed distal release, explosive medicine‑ball rotations to rehearse sequential acceleration, and metronome‑guided swings to standardize onset latencies.The table below pairs practical drills with their mechanical aims and concise coaching cues for field implementation.

| Drill | Biomechanical Aim | Coaching Cue |

|---|---|---|

| Rotational medicine‑ball toss | Reinforce proximal→distal acceleration pattern | “Start with the hips,let the torso follow,release with the hands” |

| Resistance‑band hold‑and‑release | Encourage later distal peak for better energy transfer | “Maintain tension until you feel the hip drive” |

| Metronome‑paced practice swings | Improve consistency of intersegmental timing | “Two counts back,one count through” |

Objective monitoring and graded overload are key to lasting adaptations. Use serial kinematic checks (marker or markerless motion capture, IMU arrays, or automated 2D timing) to document reductions in maladaptive latencies and restoration of proximal‑to‑distal peak ordering. Set progression criteria-such as consistent proximal‑to‑distal peak sequence across repeated swings and lower trial‑to‑trial timing variability-before increasing load or velocity. Integrate strength and motor‑control training once timing shows reliable improvement, and employ external focus instructions and auditory cues to accelerate motor learning. Sequencing evaluation, targeted drills, and monitored progression form a replicable route to more power, better accuracy, and lower injury risk.

Force Patterns, Torque Generation, and Technical Adjustments to Raise Clubhead Velocity

Ground reaction forces (GRFs) are the external impulses through which the feet and legs generate the net moments that ultimately accelerate the club. A kinetic perspective separates vertical, medial‑lateral and anterior‑posterior components and stresses the importance of when those force peaks occur relative to the kinematic sequence. Peak vertical force often reflects an effective weight shift and launch preparation, while horizontal shear supports rotational acceleration and tangential club speed. controlling the center‑of‑pressure path under the feet maximizes the lever arm for hip and trunk torque production.

Coaching cues should aim to synchronize force submission with segmental sequencing to optimize torque transfer. Practical targets include:

- Gradual lateral→vertical force strategy: coach a measured lateral push into a rapid vertical rise to extend hip extension capability.

- Ground‑to‑torso timing: time peak pelvic rotation to coincide with the downswing descent of peak GRF to boost intersegmental torque flow.

- Foot stiffness and ankle function: refine ankle dorsiflexion and midfoot stiffness to provide a stable platform for moment generation.

These cues emphasize coordinated torque creation over raw, isolated muscular force.

Objective benchmarks help translate technique work into measurable gains. Typical applied targets (context dependent) include:

| Metric | Representative Target |

|---|---|

| Peak resultant GRF | ~2.0-2.5 × bodyweight |

| Time to peak GRF (downswing→impact window) | ~120-180 ms |

| Peak hip torque | ~150-350 N·m |

| Increment in clubhead speed per program block | ~+0.5-2.0 m/s |

training should progress in phases-technique, then load, then speed-so tissues adapt safely while exploiting the nonlinear payoff of increased velocity (kinetic energy rises with the square of speed). Because modest speed gains can yield disproportionately larger energy increases at impact, prioritize precise, well‑timed force application and torque coupling rather than simply increasing muscle output. Measurable exercises-resisted lateral push‑offs, tempo‑controlled impact strikes, and accelerated rotational releases-combined with serial testing can confirm that improvements in GRF and torque produce reliable clubhead‑speed gains.

3D Capture and Markerless Tracking: Practical Best practices for Reliable Measurement

Experimental setup and calibration must minimize measurement bias before any data collection. Arrange cameras to create broad baselines and avoid collinear views, synchronize trigger signals across devices, and choose frame rates that capture the fastest swing phases (many practitioners use ≥ 240 Hz for accurate clubhead dynamics). Control lighting, backgrounds, and the floor surface to reduce noise in optical tracking and feature matching. Use a validated global coordinate system and perform multi‑step calibration (intrinsic and extrinsic) with traceable calibration objects; record reprojection error and sensor drift as session metadata.

- Camera setup: wide baseline and varied heights

- Sampling trade‑offs: frame rate vs. exposure considerations

- Participant preparation: consistent clothing and accurate anthropometric measures

- Calibration checks: verify before and after sessions

When employing markerless systems, choose algorithms and training data that reflect the target population and movement intensities. Prefer multi‑view fusion or volumetric reconstruction over single‑view pose estimation when occlusions are common (such as, during the tucked backswing). Quantify algorithmic performance by benchmarking against a gold‑standard marker set for a representative sample; report mean and worst‑case spatial errors for key anatomical landmarks and the clubhead. Keep a versioned processing pipeline so retraining and parameter changes remain auditable and reproducible.

| Metric | Marker‑based | Modern Markerless |

|---|---|---|

| Typical spatial accuracy | ~1-3 mm | ~5-15 mm |

| Recommended frame rate | 200-1000 Hz | 120-480 Hz |

| Occlusion resilience | Low | Moderate-High |

Processing and reporting should be transparent and scientifically defensible. Use biomechanically informed filters (for example, low‑pass Butterworth with cut‑off chosen via residual analysis) and document any gap‑filling or interpolation. Normalize kinematics to body segments and define event markers (address, top, impact) using explicit algorithmic rules with tolerance bands.For publication or cross‑study comparison, include uncertainty estimates, sample‑size reasoning, and make processed data and metadata (sensor models, calibration errors, pipeline versions) available when possible to enable reproducibility and secondary analysis.

Muscle Activation, Neuromuscular Strategy, and Training: Strength, Mobility and Control

High‑level swing performance depends on precise temporal coordination across muscle groups rather than maximum isolated strength. Electromyography (EMG) studies commonly show a proximal‑to‑distal activation cascade: hip extensors and trunk rotators begin torque transfer while distal muscles (forearm and wrist) time the club release. Changes in activation onset, slower rates of force development, or inefficient co‑contraction patterns reduce clubhead speed and increase load on the lumbar spine and lead wrist. Thus, assessments should weigh timing metrics (onset latencies, intermuscular coherence) in addition to traditional strength tests.

Effective physical programs must concurrently build rotational power, segmental mobility, and stabilization. Recommended components include:

- Rotational power work (medicine‑ball throws, resisted cable chops) to increase angular impulse;

- Mobility routines (thoracic rotation flows, hip internal/external rotation drills) to enable torso‑pelvis separation;

- Anti‑rotation and stability training (Pallof presses, single‑leg deadlifts) to maintain lumbopelvic stiffness during rapid transfers.

Programs should progress load while preserving movement quality to avoid compensatory patterns that disrupt sequencing.

Converting physical gains into better swing mechanics requires motor‑control focused practice. A mixed practice schedule-combining blocked technical repetitions with variable, game‑like scenarios-supports adaptability and retention. The table below provides a concise intervention matrix for field use:

| Intervention | Main Benefit | Typical Prescription |

|---|---|---|

| Medicine‑ball rotational throws | Explosive rotational power | 3-5 sets × 6-8 reps |

| Pallof press (anti‑rotation) | core stiffness and lumbopelvic control | 2-4 sets × 10-15 s holds |

| thoracic mobility series | Increase torso‑pelvis separation capacity | Daily, 2-3 sets × 8-12 reps |

Progression should be criterion‑based: track objective markers such as clubhead speed, pelvis‑thorax separation angle, and measures of rate of force development. Progress when timing variability decreases, movement quality holds under load, and the athlete remains symptom‑free. Wearables and coach cues can flag regressions early; aligning strength phases with technical coaching typically produces the best transfer to on‑course performance. Integrating neuromuscular assessment with focused interventions enhances both output and injury resilience.

Consistency, Variability and Practice Design: Statistical Methods to Reduce Error

Measuring within‑ and between‑swing variability is central to designing interventions for error reduction. Practitioners should use statistics that distinguish meaningful signal from noise: standard deviation (SD) and coefficient of variation (CV) for dispersion; root mean square error (RMSE) and mean absolute error (MAE) for trial deviations; intraclass correlation (ICC) and variance‑component estimation in mixed models to separate stable player traits from situational noise. For repeated measures, linear mixed‑effects models are often preferred because they model swings nested within sessions and quantify the within‑player variability that most strongly predicts short‑term performance swings.

turning statistical insight into practice requires specifying which variability to stabilize and which to allow for exploration. Regression or generalized additive models can show how changes in variability of key parameters (for example, clubhead‑speed SD or attack‑angle CV) affect outcomes like carry distance and lateral dispersion. from those mappings, recommended practice strategies include:

- Blocked→random progression to reduce execution errors early, then foster adaptability;

- Differential learning that varies nonessential degrees of freedom to promote exploration;

- Bandwidth feedback where small deviations are left uncorrected to encourage self‑correction.

Choose these methods based on model‑estimated effect sizes and cross‑validation of transfer to course performance.

Example session metrics and interpretations:

| Metric | Example | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| clubhead speed SD | ~1.8 mph | Low intra‑session variability; consistent power output |

| Launch angle CV | ~8% | Moderate variability; may cause distance scatter |

| Carry RMSE | ~12 yds | High outcome error; focus on dispersion control |

For operational monitoring, use statistical process control and adaptive models: CUSUM or control charts can flag systematic drift, while Bayesian hierarchical models update individualized expectations after each session. Cross‑validated learning curves reveal when returns diminish and help prescribe optimal session dosage. Treat variance improvements as key objectives alongside mean performance gains, and convert model flags into simple coaching actions (increase randomization, trigger a targeted drill, or scale back feedback) so data‑driven error reduction becomes part of routine coaching practice.

Using Launch Data to Inform technique Changes

High‑resolution launch monitors and ball‑flight data turn subjective impressions into quantitative diagnostics. Variables such as ball speed, launch angle, spin rate, clubhead speed, face‑to‑path, and attack angle create a multi‑dimensional shot profile. When these metrics are analyzed together, causal links frequently enough surface (as a notable example, elevated side spin frequently accompanies an open face at impact), enabling coaches to target mechanical faults that most plausibly explain performance losses.

An evidence‑based workflow for converting measurements into change includes:

- Baseline characterization: record representative shots under controlled conditions to establish the player’s normal metric ranges;

- Detect systematic deviations: look for persistent outliers (for example, mid‑iron spin rates consistently above expected ranges) rather than one‑off events;

- Prioritize interventions: focus on variables with the largest impact on distance or dispersion and clear mechanical causality;

- Prescribe and evaluate: choose drills or technique adjustments predicted to change the target metric and set objective success criteria.

Representative metric ranges and suggested technical fixes:

| Metric | Typical Range | Suggested Technical Change |

|---|---|---|

| Launch angle (driver) | ~10°-14° | Raise/ lower tee height, shallow attack angle, focus on center‑face strikes |

| Spin rate (driver) | ~1800-3000 rpm | tweak loft/face control and timing; emphasize forward shaft lean for irons |

| Face‑to‑path | ≈‑2° to +2° | Grip and aim adjustments; use gate or path drills to reduce sidespin |

| Angle of attack | Neutral to slightly in‑to‑out | Weight‑shift and sequencing drills to correct over‑the‑top or excessive inside‑out motions |

Implement changes iteratively and empirically: apply a focused modification, re‑collect comparable data, and evaluate results against the pre‑set targets. Consider trade‑offs (for example,reducing spin may lower stopping ability on approaches) and contextual factors such as turf interaction and player adaptability. Use constrained tasks,task‑specific drills,and progressively complex practice to transfer measured improvements into course reliability while staying aligned with launch‑monitor signals. Measurement‑guided coaching links technical adjustments to objective outcomes and fosters repeatable gains.

Operational Data‑Driven Coaching: Feedback Systems, Periodization and Progress Tracking

A structured coaching system begins with a reliable data pipeline that captures kinematic, kinetic, and performance outputs each swing. Combine high‑speed video,launch‑monitor telemetry,and wearable IMUs to build a multimodal dataset. Define a compact set of standardized, trackable metrics-such as:

- Clubhead speed (m/s)

- Attack angle (degrees)

- Sequencing latency (ms between pelvis, thorax, club peaks)

- Shot dispersion (m, 95% confidence)

- Movement variability (within‑player SD)

These core measures form the empirical basis for selecting interventions and reduce reliance on subjective impressions.

Organise work into measurable phases aligned with player capacity and competitive schedules: Diagnostic Assessment, Foundational Motor Control, targeted Technical Change, and Performance Consolidation. For each phase,specify target metric improvements,acceptable tolerances,training loads,and a drill taxonomy. Effective plans blend motor‑learning principles (variable practice, external focus) with conditioning so mechanical changes are supported physically and recovery is managed.

Progress tracking needs regular, repeated measurement and clear visualization to detect both short‑term responses and long‑term trends. A simple coach‑facing table can show baseline, short‑term target, and review cadence for priority metrics, such as:

| Metric | Baseline | short‑Term Target | Review Cadence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Clubhead speed | ~38 m/s | ~40-41 m/s | Weekly |

| Sequencing latency | ~150 ms | <120 ms | Biweekly |

| Shot dispersion | ~12 m | <8 m | Monthly |

Use control charts, moving averages, and effect‑size metrics to distinguish real improvements from measurement noise and to inform decisions to advance, maintain or regress a program. Operationalize closed‑loop feedback and decision rules-build dashboards that highlight out‑of‑range metrics, flag trends, and link annotated video to quantitative events.Recommended operational practices include:

- Weekly review meetings with athlete‑specific targets

- Pre‑defined thresholds that trigger changes in workload or technique emphasis

- Triangulation of metrics with self‑reported readiness and qualitative video review

Adopting a structured, data‑centered process ensures coaching actions are measurable, adaptive, and directly tied to performance outcomes.

Q&A

Note: automated web search results returned unrelated material rather than domain literature; the following Q&A is compiled from established biomechanical and motor‑control concepts relevant to golf swing analysis.

Q1: Which scientific fields inform rigorous study of the golf swing?

A1: The analysis is interdisciplinary-biomechanics (kinematic/kinetic description), motor control and learning, exercise physiology (energetics and fatigue), sports engineering (club/ball mechanics), and applied statistics and modelling all contribute. Each field supplies methods and perspective necessary to connect movement patterns with performance and injury outcomes.

Q2: What’s the difference between kinematics and kinetics, and why measure both?

A2: Kinematics describes the motion itself-positions, velocities, accelerations-often via motion capture. Kinetics explains why motion occurs-forces and torques-measured or inferred from force plates and inverse dynamics. together they link movement patterns to underlying causes and risk factors.

Q3: What is proximal‑to‑distal sequencing?

A3: Its the coordinated activation and acceleration from central segments (pelvis, trunk) out to shoulders, arms and club. This timing strategy leverages intersegmental inertia transfer to amplify clubhead speed. Precise timing and controlled deceleration of proximal segments are essential to minimize energy losses.

Q4: How do GRFs influence performance?

A4: GRFs are the external forces a player uses to create net moments and impulse. Their magnitude, direction and timing relative to the downswing determine rotational torque and linear accelerations that affect clubhead speed and launch conditions. Poor timing or asymmetry reduces efficiency and may raise injury risk.

Q5: How does EMG help interpret the swing?

A5: EMG indicates the timing and relative activation patterns of muscles. While amplitude must be normalized carefully to infer force, EMG combined with inverse dynamics enriches understanding of neuromuscular strategies for power and control.

Q6: How is clubhead speed modelled?

A6: Models range from empirical regressions linking anthropometrics and key segment velocities to physics‑based multi‑segment or flexible‑shaft simulations.Critical predictors include pelvis and trunk rotational velocities,wrist release timing,and efficient sequencing.

Q7: What determines accuracy biomechanically?

A7: Repeatable impact geometry (face angle, path, loft), low variability in those parameters, and effective upstream stability determine accuracy.Distal control of the clubface depends on proximal stability and finely tuned wrist/forearm control.

Q8: How should variability be interpreted?

A8: Variability can be functional. Skilled performers reduce variability in task‑critical dimensions while allowing exploration in redundant degrees of freedom. Controlled variability supports robustness to perturbations; excessive variability in critical parameters harms consistency.

Q9: What are common measurement tools and their limits?

A9: Tools include optical motion capture,IMUs,force plates,pressure insoles,high‑speed cameras,EMG,and launch monitors. Limitations include soft‑tissue artefact, IMU drift, lab constraints on natural behavior, and consumer device resolution limits. Careful calibration, filtering and multimodal fusion help mitigate these issues.

Q10: How does equipment interact with swing mechanics?

A10: club and ball properties alter boundary conditions at impact: clubhead inertia affects sensitivity to off‑center strikes, shaft flex influences timing of energy transfer, and ball construction affects spin and launch. These interactions can require technique adjustments for optimal results.

Q11: What modelling approaches are used and what do they reveal?

A11: Methods include forward dynamics musculoskeletal simulations, inverse dynamics with optimization, rigid multi‑segment models and finite‑element approaches for impact. They reveal how changes in timing,strength or geometry affect speed,joint loads and injury risk,and can identify influential parameters for targeted training.

Q12: What are common injury mechanisms?

A12: Low back pain, elbow tendinopathy and wrist/shoulder overuse arise from large torsional lumbar loads, abrupt decelerations, repetitive asymmetric loading, and poor sequencing combined with inadequate stabilization. Biomechanical analysis can quantify joint moments and highlight risky patterns.

Q13: How does fatigue change mechanics?

A13: Fatigue typically reduces force output and timing precision, increases variability, and can produce compensatory patterns that raise injury risk. Monitoring workload and prioritizing quality over quantity helps mitigate these effects.

Q14: What experimental and statistical practices matter?

A14: Good studies consider sample size and heterogeneity, use repeated‑measures designs, control confounders, select relevant outcomes, and apply mixed‑effects or hierarchical models to partition variance. Cross‑validation and replication support generalizability.

Q15: How can analytics be translated to coaching?

A15: Simplify biomechanical insights into concise cues and drills that respect individual constraints. Combine targeted conditioning, motor‑learning practice structures, biofeedback and equipment tweaks, and evaluate effectiveness with outcome metrics tied to performance and injury prevention.

Q16: What future directions look most promising?

A16: Markerless capture and wearable networks for in‑field data, subject‑specific musculoskeletal models, machine‑learning for individualized feedback, closed‑loop biofeedback systems, and longitudinal studies linking biomechanics to long‑term performance and injury are high‑value directions. Multiscale models coupling neuromuscular control with tissue loading can further integrate performance and safety.

Q17: What are limitations and ethical issues?

A17: Challenges include lab‑to‑field transfer, measurement‑induced behavior changes, and limited generalizability. Ethically, informed consent, privacy of motion and health data, and ensuring interventions do not increase injury risk are paramount. Transparent reporting and data sharing, when permitted, enhance reproducibility.

if desired, this material can be converted into a formatted FAQ, supplemented with a reading list of primary studies, or organized into lecture slides and schematics for teaching.The synthesis above attempts to unify biomechanical, physiological and technical perspectives so that the swing can be treated as a multiscale, constrained system where technique, anatomy and habitat jointly determine outcomes. Evidence‑based coaching and measurement should therefore focus on the relationships among sequencing, energy transfer and controlled variability rather than isolated metrics.Future work that links laboratory precision with on‑course behaviour, refines inter‑individual models, and tests causal interventions will best advance both performance and injury prevention. ultimately, balancing individual expression with rigorous biomechanical principles offers the most productive path forward.

Coaches’ Guide to Swing mechanics: Practical Motion-Capture Insights for Better Golf

Pick a tone

Tone chosen for this article: Practical – aimed at coaches and golfers who want actionable, data-driven guidance they can use on the range and in teaching sessions. If you prefer a scientific or punchy version, I can revise the voice and headline.

Why biomechanics + motion-capture matter for the golf swing

Modern coaching blends feel-based instruction with quantifiable data. Motion-capture systems (high-speed cameras, marker-based 3D systems, inertial sensors) reveal timing, joint angles, angular velocities, and weight transfer in ways the naked eye can miss. Using biomechanics and motion-capture, coaches can:

- Pinpoint the root cause of swing faults (timing vs. sequencing vs. alignment).

- Create repeatable metrics to track progress (clubhead speed, X‑factor, peak pelvis and thorax rotation speeds).

- Design drills that change mechanics, not just feel.

- Reduce trial-and-error practice and accelerate advancement in ball striking, distance and accuracy.

Core keywords to use with players and content

Use these keywords naturally when creating lesson plans,web pages or video descriptions to improve SEO visibility: golf swing,swing mechanics,biomechanics,motion capture,clubhead speed,swing tempo,launch angle,ball striking,golf drills,golf coach,kinematic sequence.

Essential components of an optimized golf swing

Grip mechanics and clubface control

- Neutral grip promotes consistent clubface orientation at impact. Small grip changes affect face angle and toe-hang.

- Motion-capture can show forearm rotation timing – crucial for squaring the club.

- Drill: slow‑motion swings with a mirror or camera, focusing on forearm rotation through impact (3-5 sets of 10 slow reps).

Stance, posture and alignment

- Stable base and athletic posture enable efficient force transfer from ground to ball.

- Measure knee flex,spine tilt and shoulder plane with video or sensors to ensure consistent setup.

- Tip: small variations in ball position and posture change launch angle and spin dramatically – test with launch monitor data.

Proximal-to-distal kinematic sequence

One of the most consistent findings in swing research is the proximal-to-distal sequence: pelvis initiates rotation, then torso (thorax), then arms, then club. Correct sequencing creates efficient energy transfer and maximum clubhead speed with less stress on the body.

- Motion-capture outputs show peak angular velocities in order: pelvis → thorax → lead arm → club.

- Coaching focus: restore or reinforce the sequence rather than forcing arm speed – sequencing is what creates safe power.

X‑factor and separation

X‑factor = the rotational separation between shoulders and hips at the top of the backswing. greater,controlled separation can store elastic energy for the downswing. Typical ranges:

- Recreational: 10°-25°

- High‑level amateurs / pros: 25°-45°

Motion-capture helps measure separation and whether it’s created safely with thoracic rotation rather than excessive lumbar torque.

Timing, tempo and transition

Tempo is the rhythm of the swing. Many elite players have a backswing:downswing time ratio near 3:1 (backswing about three times longer than downswing). Motion-capture and high‑speed video quantify:

- Backswing and downswing durations

- Transition time (the pause or change in acceleration at the top)

- Peak angular velocity timings for each segment

Practical tempo targets

- try a 3:1 ratio as a baseline. Example: 0.9s backswing, 0.3s downswing for a full swing rhythm.

- Consistency beats “faster” – an evenly repeatable tempo usually yields better contact and accuracy.

Clubhead speed, launch and impact mechanics

Clubhead speed correlates with distance but must be combined with optimal launch angle and spin rate to maximize carry. Motion-capture + launch monitors provide a complete picture:

- Clubhead speed (mph or kph)

- Smash factor (ball speed ÷ clubhead speed)

- Launch angle and spin rate

- Face-to-path at impact (key for accuracy)

Coaching emphasis: improve the kinematic sequence and impact conditions to increase smash factor and efficient ball speed rather than just “swing harder.”

Common faults, diagnostics and corrective drills

Below are frequent problems, how to diagnose them with motion-capture or video, and drills that help.

1) Early extension (hips move toward the ball)

- Diagnostic: pelvis moves forward during downswing; thorax angles change.

- Cause: weak glutes/poor posture or reverse pivot.

- Drill: wall‑tap drill – set ball near a low wall and practice swings without touching the wall, forcing the pelvis to rotate rather than slide.

2) Casting or early release

- diagnostic: clubhead decelerates before impact; late peak angular velocity of forearms.

- Cause: poor sequencing or trying to “hit” with the hands.

- drill: delayed release drill with impact bag – hold the angle longer and feel the club release through the bag.

3) Over-the-top/steep downswing

- Diagnostic: club path outside-to-in, early lateral shift of upper body.

- Drill: two‑tee path gate – place tees to encourage an inside takeaway and inside-downswing path.

Data-driven coaching plan (4-week sample)

Use motion-capture or an IMU-based system each week to monitor these metrics: clubhead speed, X-factor, pelvis and thorax peak rotation speeds and tempo ratio.

| Week | Focus | Key Drill | Target Metric |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Setup & Grip | Mirror grips + slow swings | consistent address posture |

| 2 | Sequencing | Step drill & pelvic rotation reps | Pelvis peak precedes thorax peak |

| 3 | Tempo & Transition | Metronome 3:1 tempo swings | Stable backswing:downswing ratio |

| 4 | Impact Quality | Impact bag + launch monitor work | Smash factor + consistent face-to-path |

Measuring progress: useful metrics and targets

- Clubhead speed (driver): recreational 70-95 mph, single-digit handicap 95-110+ mph, pros often 110+ mph. Target increases of 2-5% per month with proper mechanics and strength work.

- X‑factor (shoulder-hip separation): aim to increase separation safely (under coach guidance), often toward 25°-40° for stronger players.

- Tempo ratio (backswing:downswing): target ~3:1 for many golfers; prioritize consistency.

- Smash factor: driver ideal ~1.48-1.50 (higher indicates efficient energy transfer).

Case study snapshot: how motion-capture changed a player in 6 lessons

Summary (fictional but realistic): Amateur golfer “A” had inconsistent drives and loss of distance. Motion-capture showed early arm release and late pelvis rotation. Over six lessons focusing on hip rotation drills, delayed-release impact bag work, and tempo training with a metronome, the player achieved:

- Clubhead speed +4 mph

- smash factor improved from 1.39 to 1.45

- driving dispersion reduced by 18%

Key takeaway: small sequencing and tempo changes produced measurable gains without “swinging harder.”

Practical coaching tips for lessons and practice

- Start with baseline data: simple video or an affordable IMU system gives repeatable metrics for comparison.

- Address one mechanical change at a time. Too many simultaneous changes confuse motor learning.

- Use numeric targets (tempo ratio, X‑factor degrees, clubhead speed) instead of vague cues.

- Combine feeling cues with data. Example: “Feel the hips start the downswing” supported by measured pelvis-to-thorax timing.

- keep practice sessions short and focused – 20-30 minute blocks with specific drilling and measurement are highly effective.

SEO tip: language, regional spelling and content organization

When publishing lessons, choose keyword variations that match your target audience. For example, American English uses “optimize” while British English uses “optimise.” Keep spelling consistent across your site to avoid splitting search relevance (see: Optimize vs. Optimise explanations).1

Also prioritize semantic keywords such as “golf swing biomechanics,” “swing tempo drills,” and “motion capture golf” across headers and meta tags for better search visibility.

Tools and tech that integrate well with coaching

- 3D motion-capture systems (marker-based) – ideal for research and detailed biomechanical reports.

- IMU sensors (wearables) – affordable and useful for on-field measurements of rotation and tempo.

- launch monitors – essential to link swing mechanics to ball flight outcomes (carry, spin, launch).

- High-speed video – low-cost, high-impact for seeing impact and release timing.

Rapid reference drills (one-liners)

- Step Drill - improves sequencing and ground force use.

- Impact Bag – trains delayed release and impact feel.

- Metronome Swings – consistent tempo (start with 3:1 rhythm).

- Wall-Tap Pelvis Drill – prevents early extension and promotes rotation.

Want a shorter headline or to tailor this for golfers, coaches, or researchers?

Short headline examples by audience:

- Golfers: “Swing Better, Strike Better”

- Coaches: “Data-Driven Swing Coaching”

- Researchers: “Kinematic Insights into the Golf Swing”

Tell me the audience and tone (scientific, practical or punchy) and I’ll refine the title, meta tags and the opening paragraphs to match.

1.For guidance on regional spelling differences (optimize vs. optimise) see public explanations such as AskDifference’s “Optimize vs. Optimise.”