Handicap indices serve as a central metric in modern golf,translating heterogeneous round-by-round performance into a standardized measure of playing ability. Beyond their practical function in facilitating equitable competition, handicaps embody a synthesis of statistical principles, course architecture, and environmental variability.accurate assessment therefore demands both rigorous treatment of score distributions and careful adjustment for course-specific difficulty-factors that determine whether a handicap reliably reflects a golfer’s underlying skill or is biased by anomalous conditions.

This article examines the theoretical underpinnings and applied mechanisms that govern handicap calculation, with particular emphasis on how course characteristics and rating methodologies interact with player performance data.Key principles considered include sampling adequacy and outlier treatment, the use of differential scoring too isolate form from noise, and the formal role of course rating and slope in converting raw scores into comparable performance indices.Attention is also given to nonstatistical influences-such as tee placement, course setup, and weather-that systematically shift observed scores and thus affect handicap stability.

Through a combination of empirical analysis and conceptual synthesis, the discussion aims to disentangle the relative contributions of player skill and course effects to handicap variability.the resulting framework is intended to inform players, governing bodies, and course administrators on best practices for handicap management, course selection strategy, and policy refinement that promote both fairness and meaningful measurement of golfing ability.

Theoretical Foundations of Golf Handicapping Systems and Performance Metrics

Contemporary handicap frameworks rest on formal statistical constructs that treat a player’s recorded scores as noisy observations of an underlying performance parameter. Within this view, a handicap is an estimator: it aggregates recent score differentials and maps them, via course-specific scaling factors, to an expected stroke output.The distinction between theoretical constructs and applied practice is important here – theoretical models provide clarity about bias, variance, and convergence properties of the estimator, while operational systems must balance statistical rigor with usability and interpretability for golfers and committees.

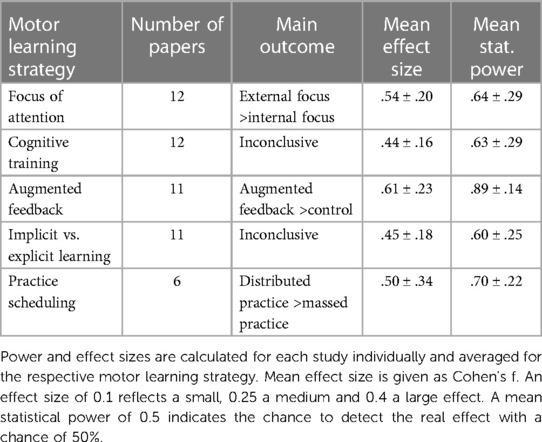

Performance metrics complement the estimator by decomposing how strokes are gained or lost across facets of play (long game, approach, short game, putting). These metrics serve both diagnostic and predictive roles: diagnostically they identify consistent skill strengths and deficiencies; predictively they refine expected-score distributions used in matchmaking and competition adjustments. The table below summarizes core metrics and their functional role in handicap and performance analytics.

| Metric | Primary Use |

|---|---|

| Score Differential | Baseline input for handicap estimation |

| Strokes Gained | Skill decomposition by shot type |

| Course Rating | Par-equivalent difficulty anchor |

| Slope | Relative challenge across player abilities |

Course architecture and situational factors impose systematic shifts that theoretical models must explicitly accommodate. Important course effects include:

- Course Rating and Slope – deterministic scalars that rescale raw differentials to a common ability metric;

- Hole-level variance – heteroskedasticity where some holes amplify skill differences more than others;

- Weather and setup - transient shifts that induce nonstationarity in observed scores;

- Tee-box selection and pin positions – design choices that change effective play strategy and variance.

models that ignore these structured sources of variation risk biased handicaps and misattributed performance signals.

Foundational statistical assumptions often invoked in handicap modeling include: distributional form of score differentials (normality is convenient but often violated), independence or explicit modeling of serial dependence, stationarity of latent ability over the calibration window (or explicit modeling of drift), and correct exchangeability of course adjustments (i.e., course rating/slope capture systematic venue effects). Violations of these assumptions produce predictable biases (e.g., non‑normal tails inflate the influence of outliers; autocorrelation underestimates uncertainty). For transparency and operational defensibility, systems should document which assumptions are made and provide diagnostics (goodness-of-fit tests, autocorrelation checks, and sensitivity analyses) to detect departures from ideal conditions.

A compact summary of common assumptions and practical implications is useful when communicating with stakeholders:

| Assumption | Statistical Form | Practical Effect |

|---|---|---|

| Normality | Symmetric, finite‑variance | Stable mean/variance estimators; vulnerable to heavy tails |

| Independence | No serial correlation | Valid standard errors; otherwise need time-series models |

| Correct course adjustment | Fixed, unbiased offsets | Comparable indices across venues; misadjustment biases ability |

When assumptions are tenuous, hierarchical (mixed) models or Bayesian updating provide principled routes to incorporate temporal drift, heteroskedasticity, and prior information while yielding calibrated uncertainty estimates. Ultimately, treating handicap algorithms as theoretical constructs subject to empirical falsification improves fairness, predictive value, and the capacity to optimize gameplay decisions based on a more defensible representation of individual ability.

For operational clarity, practitioners should publish model diagnostics and offer simplified explanations (e.g., when a player’s index is flagged for instability, what tests were run and what remedial steps ensued). Emphasizing both robust estimation and skill decomposition yields a system that is analytically defensible and operationally useful for improving play and competitive fairness.

methodological Considerations in Handicap Calculation and Data Integrity

Robust study design begins with predefined score-selection rules and exclusion criteria to limit bias in handicap estimation. Score inclusion windows (e.g., most recent N rounds versus best-of-N) materially alter variance and trend detection; therefore explicit justification for the chosen window must be provided. Attention to sample size and representativeness of playing conditions (seasonality, course mix, tees played) is essential to avoid overfitting local course effects. To operationalize these choices, researchers should document:

- inclusion criteria for rounds and players

- Temporal aggregation logic (rolling vs fixed windows)

- handling of incomplete or social rounds

This explicit methodological scaffolding reduces analytic ambiguity and supports reproducible handicap estimates.

An important operational topic is outlier detection and robust aggregation. Empirical score distributions are often right‑skewed with heavy upper tails (occasional high‑score rounds), so mean‑based indices without protection can be unstable. Practical, reproducible strategies include:

- Robust central tendency and dispersion: trimmed means, median absolute deviation (MAD), and M‑estimators (e.g., Huber or Tukey biweight).

- Outlier detection: modified Z‑scores based on MAD, IQR fences applied to a player’s recent-season distribution.

- Treatment rules: winsorization (capping extremes), light trimming (5-10%), or using heavy‑tailed likelihoods (Student‑t) rather than unconditional deletion.

- Hierarchical pooling: multilevel models that shrink low‑volume players toward population averages to stabilize indices.

These choices trade off robustness and complexity; the following compact comparison may guide policy selection:

| Method | Robustness | Complexity |

|---|---|---|

| Median / MAD | High | Low |

| Winsorization | Moderate | Low |

| Student‑t likelihood | High | Moderate |

| Hierarchical Bayesian | High | High |

Maintaining data integrity requires layered validation: automated checks,manual audits,and provenance tracking. Below is a concise sample checklist with rationale that can be embedded into workflow pipelines; it is intentionally minimal to serve as a template for extension in operational settings.

| Check | Rationale |

|---|---|

| Range validation | Detect impossible scores and input errors |

| Time stamp consistency | Ensure chronological ordering for form analysis |

| Course metadata match | prevent misapplication of rating/slope |

In addition, provenance metadata (user ID, device, manual edits) should be retained for each record to enable forensic review and correction. Operational systems should also adopt version-controlled handicap algorithms and an auditable change-management process; cryptographic or controlled-access logging for administrative changes ensures any modification can be traced to an authorized agent.

Adjustment mechanisms that translate raw scores into an index must remain transparent and statistically defensible. The request of course rating and slope multipliers, plus any course-specific correction factors, should be accompanied by uncertainty estimates and sensitivity analyses. Rounding rules and truncation thresholds often introduce small systematic biases; these should be reported and, where possible, corrected via bias-reduction techniques (e.g.,shrinkage estimators or Bayesian hierarchical models for low-sample courses). Consideration must also be given to differential tee effects and the aggregation of multi-tee data into a single player index.

Analytic reproducibility and ethical data practices close the loop between methodology and implementation. Authors and system designers should publish model specifications, code snippets, and a minimal dataset or synthetic equivalent to allow independent validation. Recommended reporting items include:

- Parameter definitions and estimation procedures

- Data-cleaning rules and exclusion logs

- Uncertainty quantification for indices

- Privacy safeguards for participant records

Adherence to these reporting standards fosters trust among players, clubs, and researchers while enabling continuous methodological refinement.

Course rating and Slope Analysis: Translating Course Difficulty into Handicap Adjustments

The allocation of a numeric handicap to a particular round is governed by two complementary course metrics: the course rating (an estimate of the expected score for a scratch golfer) and the slope rating (a measure of relative difficulty for a bogey golfer versus a scratch golfer). Course rating anchors the baseline performance expectation, while slope rescales the observed score differential to reflect variability in player ability across varied layouts.Analytically, treating the rating pair as orthogonal components-central tendency (rating) and dispersion (slope)-permits rigorous adjustment of raw scores so that handicaps remain comparable across disparate venues.

Quantitatively the conversion used in internationally recognized systems applies a normalization factor that accounts for slope: Differential = (Adjusted Gross Score − Course Rating) × 113 / Slope. this expression yields a standardized metric that can be aggregated into an index.The following concise table illustrates how the normalization factor (113/Slope) changes with representative slope ratings, clarifying its effect on the computed differential:

| Slope | Normalization (113/Slope) | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| 113 | 1.00 | Baseline scaling |

| 130 | 0.87 | Higher slope reduces per-shot differential |

| 95 | 1.19 | Lower slope amplifies per-shot differential |

An explicit Playing Conditions Index (PCI) as a time-varying moderator can improve fairness by separating long-run design-derived difficulty (course rating, slope) from short-run environmental perturbations (wind, pin position, green speed). At the model level, a layered specification – for example, a mixed‑effects model with player random intercepts and slopes for course difficulty metrics, plus interaction terms between slope and PCI – allows decomposition of score residuals into latent ability, structural course effects, and transient playing conditions. When linearity assumptions are strained, semiparametric extensions (splines) or constrained tree ensembles may be used, but maintain explainability for adjudication.

Typical feature scales and starting weights used during early model development can be helpful as tuning priors; these should be recalibrated with empirical federation data:

| Feature | Typical Range | Initial Weight |

|---|---|---|

| Course rating | 67-77 | 0.45 |

| Slope | 55-155 | 0.30 |

| Playing Conditions Index (PCI) | −3 to +3 | 0.25 |

Practical deployment requires governance rules and ongoing monitoring. Key operational practices include periodic recalibration of weights and priors to reflect seasonal changes and equipment evolution; uncertainty quantification (confidence intervals for handicaps and predictive distributions for expected scores); and transparent publication of model specifications and simplified correction tables for players and committees. Equity checks that simulate cross‑course transfers help detect systematic bias against player subsets or venues.

Environmental and Temporal Factors Affecting Handicap Reliability

Environmental variability imposes systematic and random effects on scoring that degrade the stability of handicap estimators.factors such as **wind velocity**, **precipitation**, **temperature**, **relative humidity**, and **green pace** alter shot dispersion, putting and approach behavior, and recovery probabilities. Small, cumulative changes (for example, a consistent 10-15% reduction in roll on firm fairways) can shift expected scores by measurable fractions of a stroke per hole; larger perturbations (sustained high wind or heavy rain) produce heteroskedastic score distributions that inflate variance and increase the likelihood of extreme rounds. To capture these impacts analytically, models should treat environmental covariates as either fixed effects (when predictable) or stochastic drivers of error variance.

The reliability of handicap records is also time-dependent: **time of day**, **season**, and **course maintenance cycles** produce structured temporal patterns that bias longitudinal comparisons. Morning versus afternoon tee times may exhibit systematic scoring differences due to dew, frost, or pin placements; seasonal green growth cycles affect putting speed and hole locations; and scheduled aeration or irrigation windows can temporarily change playability. Quantitative diagnostics for temporal coherence include stationarity and structural-break tests (augmented Dickey‑Fuller, KPSS) and Bayesian change‑point detection to determine whether observed fluctuations reflect noise, persistent drift, or regime shifts.

Robust variance estimation and temporal modeling are essential. Practical approaches include rolling‑window variance for local volatility assessment; state‑space / Kalman filtering to decompose latent skill and observation noise; and hierarchical Bayesian models that pool information across players and courses while estimating individual‑level variance components. For forecasting handicap trajectories, simple autoregressive (AR) methods work for short horizons, while Kalman filters and Gaussian processes provide smooth latent skill evolution and principled uncertainty intervals.

| Model | Forecast Horizon | Strength |

|---|---|---|

| AR(1) | 1-4 rounds | Fast, interpretable |

| Kalman filter | 1-12 rounds | Good noise separation |

| Gaussian Process | Variable | Flexible, full uncertainty quantification |

Translating temporal inference into practice implies actionable monitoring and decision thresholds. Example operational rules: compute rolling variance and forecast intervals, then reassess handicap policy when predicted index shifts exceed two times the estimated between‑round standard deviation; increase measurement frequency or apply targeted interventions when volatility rises above historical norms; and report forecast quantiles (e.g., 10th-90th) rather than point estimates to convey risk.

Because environmental and temporal factors interact, a multi-factor approach is necessary to preserve handicap fairness. Statistical strategies include:

- covariate adjustment in handicap algorithms (incorporating wind, temperature, and green speed),

- stratified indexing by season or course-condition bands to reduce within-stratum variance,

- robust outlier handling to mitigate occasional extreme-weather rounds that unduly distort a player’s index.

Routine metadata collection (e.g., recorded wind speed, turf condition, and tee time) enables these methods and improves model identifiability.

For policy and practice, committees and rating authorities should adopt procedures that recognize environmental and temporal uncertainty: require voluntary condition annotations on scorecards, schedule major rating updates after stable maintenance cycles, and employ weather‑adjusted course ratings when deviations exceed predefined thresholds. Emphasizing consistency in measurement, transparent adjustment rules, and sufficient sample sizes will preserve the handicap system’s integrity while acknowledging the inherent variability introduced by nature and time.

Strategic Applications: Tailoring Course Selection and Shot Planning to Handicap Profiles

Course selection informed by a player’s handicap transforms binary notions of “hard” and “easy” into a graded optimization problem: which features of a given layout maximize growth, enjoyment, and score consistency for that handicap profile. low-handicap players generally extract value from length, firm fairways, and penal rough because these features preferentially test distance control and shotmaking; by contrast, high-handicap players gain more from forgiving fairway widths, receptive greens, and routing that minimizes penal recovery shots. Adopting a **banded approach** to course selection allows players and coaches to prioritize developmental stimuli (technical demands) versus playability (psychological reward), thereby aligning competitive objectives with measurable exposure to relevant challenges.

A practical translation of handicap-aware strategy into day-to-day shot planning requires clear tactical templates for each band. Use the following concise prescriptions when preparing for a round:

- Low handicap (0-6): accept higher volatility off the tee in exchange for approach chances; emphasize aggressive lines and creative short-game solutions.

- Mid handicap (7-16): Balance distance with target accuracy; prioritize par-saving wedges and positional tee strategy to limit big numbers.

- High handicap (17+): Maximize margin for error: select loft/club combinations that keep the ball in play, avoid heavily penal hazards, and play conservative to small targets.

These templates are not prescriptive prescriptions but decision heuristics-players should adapt them to transient conditions (wind, pin placement) and personal form on the day.

To operationalize course-choice and shot-planning decisions, consider a compact decision matrix that links handicap band to primary course attributes to emphasize.The table below offers a short, actionable mapping useful for pre-round planning and coach-led curriculum design.

| Handicap Band | Primary Priority | Course Feature to Seek |

|---|---|---|

| 0-6 | Shotmaking & Risk | Length, firm runouts, strategic bunkering |

| 7-16 | Balance & Consistency | varied shot shapes, receptive greens |

| 17+ | Playability & Recovery | Wide landing areas, gradual hazards |

effective integration of handicap-informed strategy requires iterative feedback: record which course characteristics consistently produce better outcomes for each player and incorporate those findings into practice objectives and mental routines. Coaches should couple technical drills with scenario-based practice that mirrors the tactical templates above, and players should maintain a short pre-round checklist that reflects their handicap-tailored priorities (e.g., “play for center of fairway”, “leave approach below the hole”). community discourse-such as equipment and tactical threads on specialist forums-often amplifies these trends, but empirical tracking of on-course performance remains the most reliable method to refine course selection and shot planning across handicap profiles.

Performance Diagnostics: Identifying Strengths, Weaknesses, and Practice Priorities from Handicap Data

A rigorous diagnostic framework treats the handicap index not as a single performance marker but as an aggregate signal composed of discrete skill contributions and course-specific effects. By decomposing handicap differentials into within‑round variance (shot execution,course management) and between‑course variance (slope,length,hazard density),one can isolate persistent weaknesses from transient noise. **Handicap differentials, round-to-round variability, and stroke‑category breakdowns (driving, approaching, short game, putting)** form the core inputs for a replicable diagnostic protocol that links observed scores to actionable skill domains.

Comparative summaries across handicap bands help translate abstract indices into concrete practice targets. The table below, presented in a concise form for interpretive clarity, illustrates typical metric profiles and implied priorities across three representative handicap cohorts.

| Handicap Band | GIR % | Scrambling % | putts/Round | Primary Focus |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low (0-9) | 65-75 | 50-60 | 28-30 | Course Management |

| Mid (10-18) | 45-60 | 40-50 | 31-33 | Approach precision |

| High (19-28) | 30-45 | 30-40 | 34-37 | Short Game & Consistency |

- Data collection: log 20-40 competitive or casual rounds with shot‑level tags when possible.

- Segmentation: separate performance by shot category, hole type (par 3/4/5), and course difficulty.

- Comparison: compute moving averages and percentiles to identify persistent deficits vs. episodic outliers.

- Prioritization: allocate practice resources to skills with the largest expected strokes‑saved per hour.

Statistical discipline is essential to avoid overfitting practice plans to noise. Use measures such as standard deviation of round scores, confidence intervals for metric estimates, and simple regression to estimate how much a given metric (e.g., GIR) explains handicap variance. A minimum effective sample is typically 20 rounds for coarse inference and 40+ for reliable shot‑level decomposition; where sample size is constrained, weight recent rounds modestly and report uncertainty. **Effect sizes and confidence bounds** should guide whether an observed deficit warrants strategic intervention or continued monitoring.

translate diagnostic outputs into a prioritized,time‑bound practice syllabus that balances technical work,short game repetition,and tactical play. For example, if diagnostics show high putts/round but reasonable scrambling, allocate a greater proportion of weekly hours to putting drills and pressure simulations; if GIR is low while putts are acceptable, emphasize approach shot target practice and course‑specific shot shaping. Monitor progress using rolling handicap differentials and periodic re‑assessment of the same metrics; this closes the diagnostic loop and ensures that **practice priorities remain evidence‑based and outcome‑oriented**.

Policy Implications and Recommendations for Handicap Management and Player Development

Effective management of handicapping systems has direct policy implications for competitive integrity, access, and player progression.Policy frameworks should prioritize **accuracy**, **equity**, and **transparency**: accurate measurement of performance across diverse course conditions; equitable allowance for course-specific difficulty so that handicaps remain comparable; and transparent methodologies that players, clubs, and associations can audit. Empirical monitoring-drawing on both formal competition data and peripheral sources such as player-reported outcomes on community platforms-can reveal systematic deviations that require regulatory response.

Concrete recommendations to operationalize these principles include targeted governance and technical initiatives. Key actions are:

- Standardized data capture: mandate digital score submission formats and metadata (tee, course rating, slope, weather) to enable consistent analytics.

- Regular course re-rating: require periodic re-evaluation of course and tee difficulty especially after renovations or significant environmental change.

- Education and outreach: implement certification programs for clubs and referees on handicap calculation, appeals, and fair play.

- Stakeholder engagement: incorporate feedback loops with players, coaches, and industry forums to detect equipment- or perception-driven bias.

To strengthen governance and operational resilience, administrations should adopt technical controls: version-controlled handicap algorithms, immutable score provenance (time-stamped, user/ device identifiers), controlled-access or cryptographic logging for administrative changes, automated anomaly detection that flags suspicious submission patterns (rather than automatically rejecting them), and a defined appeals and corrections protocol with SLAs and an independent review panel. Public KPIs-such as verification latency, percent of flagged rounds, and appeal resolution time-should be reported regularly to build trust.

Simulation‑based evaluation is a practical tool for policy testing. Hybrid Monte Carlo / agent‑based simulations calibrated to historical scorecards can compare candidate rules (static caps, adaptive caps, dynamic banding, hole‑by‑hole adjustments) using equity and performance metrics such as win probability parity, handicap‑outcome correlation, score variance reduction, and a fairness index. Results from such experiments typically support policy levers that improve parity without unduly eroding skill signal; recommended levers include adaptive caps responsive to population dispersion, refined slope weighting on extreme holes, and format‑specific adjustments (match play vs. stroke play).

To assist decision-makers, the following compact reference might potentially be used to prioritize short-term versus long-term measures:

| Policy Focus | Short Action | Priority |

|---|---|---|

| Data Quality | Enforce digital scorecards | High |

| Course Rating | Re-rate high-use courses biennially | Medium |

| Player Education | Launch online modules | High |

Complementary governance measures should include audit protocols and published metrics so that changes to handicapping methodology can be evaluated against observed outcomes. Administrators should also schedule periodic model recalibration (annual for course‑level parameters, more frequent interim checks after major shocks) and maintain a rolling validation program that uses holdout sets and cross‑validation to monitor predictive validity.

From a player-development perspective, handicaps should be framed as diagnostic tools that inform individualized training plans, not as static labels. Policies should encourage clubs to integrate handicap analytics into coaching pathways-using **trend-based targets**, stage-appropriate skill objectives, and mentorship schemes-to accelerate improvement while preserving competitive fairness. adopt an iterative evaluation cycle: implement pilot changes, measure impacts on participation and competitiveness, and refine policy to balance player development goals with the need for robust, comparable handicapping across courses and regions.

Q&A

Note on sources

– The web search results provided were unrelated to golf handicaps. The following Q&A draws on established handicap principles (World Handicap System and common practice) and presents them in an academic, professional format.Q1. What is the purpose of a golf handicap?

A1. A golf handicap is a standardized metric designed to quantify a player’s potential scoring ability so players of different abilities can compete equitably.It isolates a golfer’s expected stroke-differential relative to course difficulty, enabling fair net scoring across varied courses and tees.

Q2. what are the principal components of the modern handicapping framework?

A2. the principal components are: (1) the Handicap Index (a portable measure of ability), (2) Course Rating (expected score for a scratch golfer), (3) Slope Rating (relative difficulty for a bogey golfer, standard base 113), (4) Score Differentials (individual score adjustments relative to course/tee difficulty), and (5) Course Handicap/Playing Handicap conversions and competition allowances.

Q3. How is a Score Differential calculated?

A3. A score differential represents how a posted adjusted gross score compares to the measured difficulty of the course/tee. The commonly used formula is: Score Differential = (Adjusted Gross Score − Course Rating) × 113 / Slope Rating. Adjusted scores reflect maximum-hole limits (e.g., net double bogey) and other posting rules.

Q4.How is a Handicap index derived from Score Differentials?

A4. The Handicap Index is computed from a set of recent score differentials to represent a player’s potential. Under contemporary systems, it is indeed typically based on the average of the best subset of the most recent 20 differentials (such as, the best 8 of 20) with additional rules (e.g., caps and rounding) to control volatility and limit undue upward movement.

Q5. What is the difference between a Handicap index and a Course Handicap?

A5. The Handicap Index is a portable, course-independent indicator of ability. The Course Handicap translates the Index to the stroke allowance for a specific course and tee, using the Slope and Course Rating. The usual formula is: Course Handicap = Handicap Index × (Slope Rating / 113) + (Course Rating − Par), rounded according to policy.

Q6. What is a Playing Handicap and when is it used?

A6.A Playing Handicap is an adjusted Course Handicap used for a particular competition format. It incorporates an allowance (percentage) to reflect format-specific considerations (e.g.,match play,four-ball),ensuring the net strokes offered are appropriate for the format.

Q7.What is Net Double Bogey and why is it important?

A7.Net Double Bogey is a maximum-hole score used when posting scores for handicap purposes.It equals Par + 2 − handicap strokes received on the hole. This limit reduces the influence of a single very poor hole on a posted score and improves stability and fairness of the Handicap Index calculation.

Q8. How do course rating and slope rating affect equitable competition?

A8. Course Rating sets the baseline expected score for a scratch golfer; Slope Rating scales the course difficulty relative to a bogey golfer and standardizes comparisons across courses (base slope = 113). Together they adjust raw scores so that a score’s significance is comparable irrespective of which course or tees were played.

Q9. How are playing conditions and daily variations addressed?

A9. Handicap systems use mechanisms such as a Playing Conditions Calculation (PCC) or similar adjustments to account for unusual daily factors (weather, course set-up) if overall scores on a given day deviate systematically from expected. These automated or committee-applied adjustments help preserve fairness.

Q10. What measures exist to control index inflation or rapid movement?

A10. Contemporary systems incorporate caps: soft caps (reducing increases beyond a threshold) and hard caps (preventing increases beyond a defined limit), plus verification processes and maximum score posting rules. These controls maintain index integrity and limit distortions from small samples or exceptional rounds.

Q11. How reliable is a handicap Index statistically?

A11. Reliability increases with score history size and consistency of playing conditions. twenty scores is commonly recommended to establish a stable index; fewer scores increase sampling error. Statistical measures-standard error, confidence intervals, and autocorrelation-can be used in research to quantify index stability and predictive validity.

Q12. What are the main limitations of handicaps as measures of ability?

A12. handicaps primarily measure stroke-scoring potential over a full round and are less informative about specific skills (driving, approach, short game, putting), hole-by-hole variance, course-management decision-making, or match-play acumen. They can also be affected by course rating errors, noncompliant score posting, or inconsistent conditions.

Q13. How should players use handicaps to select tees and manage strategy?

A13. Players should select tees where their Course Handicap yields an enjoyable, appropriately challenging round (many clubs aim for average gross scores in a specified range). Strategically, understanding one’s net strokes on particular holes informs risk-reward decisions-players can be more aggressive on holes where they will receive multiple strokes and conservative where they concede none.

Q14. How do handicaps differ in match play versus stroke play competition?

A14. In match play, strokes are applied hole-by-hole according to the Course handicap; playing handicaps (allowances) often reduce stroke allotments to preserve the strategic nature of match play. In stroke play, net total scores determine results; handicaps directly adjust stroke totals. Competition committees should set and publish allowances to maintain clarity.

Q15. What governance and quality-control processes are involved in course/tee ratings?

A15. Course and slope ratings are produced by authorized raters following standardized manuals and procedures-surveying yardages, obstacle positioning, green surfaces, and course length. Periodic re-rating and oversight by a governing authority ensure ratings reflect current course conditions and changes.

Q16. What practical recommendations should clubs and players follow to maintain handicap integrity?

A16. clubs should ensure accurate course/tee ratings,enforce score-posting policies (including maximum-hole limits),apply PCC and caps as prescribed,and educate members about posting requirements and competition allowances.Players should post all acceptable scores, select appropriate tees, and update scores promptly.

Q17. How can researchers contribute to improving handicap systems?

A17. Researchers can analyze predictive validity (how well indices predict future scores), robustness to small-sample and heterogeneous conditions, effects of slope-rating accuracy, bias introduced by non-random practice rounds, and optimal algorithms for volatility control. Experimental and longitudinal studies, using large score databases, are especially valuable.

Q18. What are recommended metrics for evaluating handicap-system performance?

A18. Key metrics include predictive error (mean absolute error of predicted vs. actual scores), stability (variance of index changes over time), fairness (comparative net-score distributions across courses), sensitivity to playing conditions, and compliance measures (rate of unposted or misposted scores).

Q19. How should anomalies (e.g., injured players, exceptional weather) be handled?

A19. committees should provide guidance: allow temporary suspension of handicap submission for injury, use PCC or event-specific adjustments for exceptional weather, and allow review/adjustment in documented cases. Transparency and documentation reduce disputes.

Q20. Summary: What are the central takeaways about assessing handicaps and course effects?

A20. Handicaps synthesize individual performance and course difficulty into a portable measure that facilitates equitable competition. Accurate course/tee ratings, appropriate slope application, rigorous score-posting protocols, and mechanisms to adjust for daily conditions are essential. While handicaps are robust for round-by-round comparisons, they have limits and should be complemented by additional metrics for granular skill assessment and research-driven improvements.

If you would like, I can:

– Convert this Q&A into a formal FAQ for publication.

– Expand specific answers with equations, worked numerical examples, or citations to the World Handicap System and national association documents.

In closing, this study has underscored that a rigorous assessment of golf handicaps requires both a principled statistical foundation and careful accounting for course-specific effects. Core principles-reliability of score aggregation,normalization for variability,and transparent adjustment mechanisms-must be integrated with course ratings,slope,and environmental/contextual variables to produce handicaps that are equitable and predictive. The interaction between player performance distributions and course difficulty emerges as central to interpreting handicaps meaningfully across settings.

The practical implications are multifold. For players, refined handicap facts supports more informed course selection, strategic decision-making on shot placement, and realistic goal-setting. For clubs and governing bodies, adopting standardized, data-driven rating practices improves competitive fairness and enhances matchmaking for events. Moreover, administrators should prioritize measurement consistency, clear communication of handicap derivation, and mechanisms that mitigate gaming or bias.

Limitations of the present analysis point to avenues for further inquiry. Future research should leverage larger, longitudinal datasets and incorporate advanced modeling techniques (e.g., hierarchical models, time-series methods, and machine learning approaches) to capture within-player trajectories and contextual heterogeneity. Integrating high-resolution telemetry (shot-tracking, weather, and turf conditions) and testing models across diverse populations and formats will strengthen external validity and operational applicability.

Ultimately, improving handicap assessment is both a technical and governance challenge that, when addressed collaboratively, enhances competitive integrity and player experience. Evidence-based refinement of handicap systems-grounded in transparent methodology and continuous evaluation-will better align measured ability with on-course performance and support the ongoing optimization of play, training, and competition design.

Assessing Golf Handicaps: Principles and Course Effects

Understanding Handicap Basics

Golf handicap systems exist to measure a golfer’s potential and to level the playing field across different skill levels. Whether you’re tracking a handicap index, calculating a course handicap, or posting a net score, the purpose remains the same: to express ability in a standardized way so golfers of different abilities can compete fairly.

Key terms every golfer should know

- Handicap Index – A portable measure of a golfer’s potential ability based on recent scores.

- Course Handicap – Handicap Index adjusted for a specific course and set of tees (accounts for slope and course rating).

- Course Rating – Expected score for a scratch golfer under normal conditions.

- Slope Rating – A measure of how much more challenging a course is for a bogey golfer compared to a scratch golfer (standardized to 113).

- Handicap Differential – The value calculated for each round used to build a handicap Index.

- playing Handicap – Course Handicap adjusted for format of play (match play, foursomes, stableford allowances).

How Course Rating and Slope Affect Handicaps

Course Rating and Slope Rating are central to fair handicap calculation. They convert your Handicap Index into a Course Handicap that reflects the challenge posed by a particular course and tee.

Why Course Rating matters

The course rating estimates what a scratch golfer (0.0 Handicap Index) will score on that course. If a course rating is above par, it means even scratch golfers can expect to shoot over par; that influences the net-strokes you receive and how differentials are calculated.

Why Slope matters

Slope compares how much more challenging a course is for a bogey golfer compared to a scratch golfer.A slope higher than the standard 113 increases the conversion factor from handicap Index to Course Handicap – effectively giving higher-handicap players proportionally more strokes on tougher courses.

Formulas and Practical Calculations

below are the essential formulas you’ll use when assessing handicaps and posting scores.

- Handicap Differential (per round) = (Adjusted Gross Score − Course Rating) × 113 / Slope Rating

- Handicap index = Average of the best differentials from recent rounds (commonly the best 8 of the most recent 20), subject to caps and adjustments

- Course Handicap = Handicap Index × (Slope Rating / 113) + (Course Rating − Par)

- Playing Handicap = Course Handicap × Handicap Allowance (based on format)

Note: different jurisdictions may include additional caps, manual adjustments, or local rules. Always confirm rules with your club or national association if you’re unsure.

handicap Differentials and Score Posting

Accurate score posting is crucial: your Handicap Index depends on your posted differentials. To keep your handicap meaningful:

- Post every acceptable round, including casual rounds if your association requires it.

- Use the Equitable Stroke Control (ESC) or Net Double Bogey rules when adjusting hole scores before calculating the adjusted gross score.

- Record the tees played,course rating,and slope-this data is required to compute the differential correctly.

What to watch for when posting

- Weather and course setup can skew scores; the handicap system has mechanisms (daily buffers and exceptional score reduction) to limit volatility.

- Net double bogey is the maximum hole score for handicap posting in many associations-apply it consistently.

- For tournament rounds,keep formats documented (e.g., stroke play vs stableford) as playing handicap allowances differ.

Course Effects: Tee Selection, Yardage, and Setup

Your Course Handicap will change depending on which tees you play. When analyzing course effects, consider:

- Tee yardage – Longer tees increase course rating and typically slope; strokes received will increase for longer tees.

- Hazards and forced carries – These influence the course rating and add complexity for mid- to high-handicap players.

- Green complexity – Fast, undulating greens raise the course rating because they increase the expected number of strokes for a scratch player.

- Rough height and fairway width – Tighter fairways and penal rough disproportionately affect higher-handicap players and are reflected in slope.

Choosing the right tees

Pick tees that match your average driving distance and promote enjoyable, pace-of-play-pleasant rounds. Playing from tees that are too long overstates your difficulty and inflates your Course Handicap for that round.

Practical Tips to Optimize Play Using Your Handicap

Use your handicap as a strategic tool on the course. Here are actionable tips to lower scores and improve course management:

- Work on short-game and putting first-these areas usually yield the highest return on strokes-saved.

- Use your course handicap to set realistic goals: if your Course Handicap is 18, aim for bogey-to-par golf on average holes rather than chasing birdies.

- Leverage hole-by-hole strategy: on holes where you receive strokes, play more conservatively to secure pars or bogeys rather than aggressive plays that produce big numbers.

- Track stats against your handicap: fairways hit, greens in regulation (GIR), up-and-downs-know where you leak strokes.

- Adjust tee choice based on wind and course setup to keep the game within your strengths.

Hole-by-Hole analysis and Course Management

A hole-by-hole plan guided by your handicap helps you make decisions that reduce variance and lower your typical score.

How to build a hole strategy

- Identify the holes where you receive handicap strokes – these are target holes to play conservatively for pars or comfortable bogeys.

- For holes where you don’t receive strokes, be prepared to accept bogey and save riskier plays for better opportunities.

- On long par 4s or par 5s where your driving distance is a relative weakness, favor positional play (lay-up) to the best approach distance for your wedge game.

- Use ”safe” club choices on approach shots into heavily penalized greens-minimizing big numbers improves net scores relative to your handicap.

Case Study: Applying Handicap to Strategy (Example)

Here’s a simple example showing the practical effect of course rating and slope on stroke allowances.

| Tees | Course Rating | Slope | Handicap Index 12.4 → Course Handicap |

|---|---|---|---|

| Blue (Champ) | 74.2 | 138 | 15 |

| White (Men) | 71.0 | 125 | 13 |

| Gold (Forward) | 68.5 | 115 | 11 |

Interpretation: The same Handicap Index produces different Course Handicaps. From the championship tees the player gets more strokes (15) than from the forward tees (11), changing strategy on which holes to be aggressive.

Common mistakes and How to Avoid Them

- Not posting all rounds: Incomplete data can make your Handicap Index less representative. Post all acceptable rounds.

- Playing the wrong tees: If you play tees that are too long for your game, you’ll get strokes that don’t match your actual play, and your score strategy may suffer.

- ignoring course setup changes: Temporary tees, tournament pin placements, or wind can change effective difficulty-note unusual conditions when posting.

- Confusing gross and net targets: Use gross score goals for personal skill enhancement and net score goals when competing with handicap allowances.

Quick Reference: Handicap Workflow

- Play and post adjusted gross score (apply net double bogey if required).

- Calculate Handicap Differential for the round.

- Update Handicap Index based on average of best differentials (and applicable caps).

- Convert Handicap Index to Course Handicap for the tees you will play.

- Apply playing handicap allowance based on format (match play, foursomes, etc.).

Resources and Notes

Official handicap calculation rules and definitions are maintained by national associations and the governing bodies that administer the World Handicap System (WHS). The simple formulas and strategies here are intended as practical guidance.

Note about search results: the provided web search results referenced unrelated dictionary entries and were not relevant to this article’s subject.The guidance in this article is based on standard handicap principles (course rating, slope, handicap differentials, and Course Handicap calculations) commonly used by handicap systems worldwide.