The golf swing represents a highly coordinated, multisegmental motor task in which rapid generation and transfer of mechanical energy through the kinetic chain determine both performance outcomes and injury risk. A nuanced understanding of joint kinematics, intersegmental coordination, muscle activation patterns, and external force interactions is therefore indispensable for optimizing clubhead velocity, launch conditions, and shot consistency while minimizing deleterious loading on the lumbar spine, shoulders, and wrists. Recent advances in motion-capture technology, force-platform analysis, electromyography, and musculoskeletal modeling have enabled increasingly detailed quantification of the mechanical and neuromuscular determinants of effective swing mechanics, yet translation of these insights into individualized training and clinical interventions remains incomplete.

Key biomechanical constructs-proximal-to-distal sequencing, pelvis-torso separation (X-factor), stretch-shortening cycle utilization, ground-reaction force generation, and segmental timing-collectively influence the magnitude and rate of energy transfer to the clubhead and ball. Quantitative assessment typically employs inverse dynamics to estimate joint moments and powers, electromyography to characterize muscle recruitment and timing, and optimization-based simulations to evaluate option movement strategies under physiological constraints. These methodological approaches facilitate identification of performance-limiting patterns (e.g., altered timing, inadequate lower-limb bracing) and injury-prone loading profiles (e.g., excessive lumbar shear or torsion), thereby creating pathways for targeted technical, conditioning, and equipment interventions.

This article synthesizes current biomechanical evidence on the golf swing, evaluates analytical and modeling methodologies for performance optimization, and delineates practical strategies for technique modification and injury prevention. Emphasis is placed on integrating quantitative findings with applied coaching and rehabilitation practices, highlighting areas where predictive modeling, wearable sensor analytics, and individualized training prescriptions can bridge the gap between laboratory insight and on-course performance. Recommendations for future research are presented to advance mechanistic understanding and to support evidence-based interventions that maximize both player performance and musculoskeletal health.

Kinematic Chain and Temporal sequencing in the Golf Swing: Mechanisms of Energy Transfer and Training Recommendations

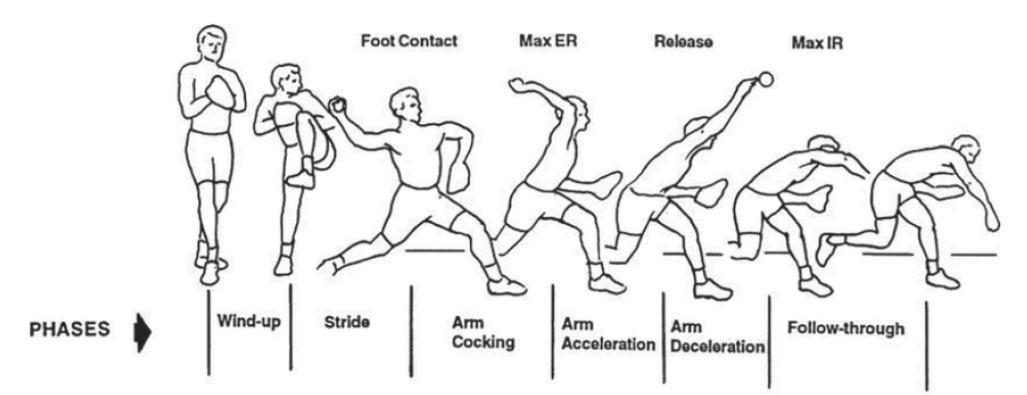

Proximal-to-distal sequencing in the golf swing describes the ordered activation and acceleration of body segments-pelvis → thorax → upper arm → forearm → club-so that peak angular velocities occur progressively from the largest, proximal segments to the smallest, distal segments. This segmental cascade optimizes transfer of mechanical energy and angular momentum while minimizing internal joint loading when timing is precise. Ground reaction forces (GRF) act as the initial external impulse,converted by the hips into pelvic rotation; intersegmental torques and intermuscular force transmission then amplify clubhead speed through coordinated eccentric-to-concentric muscle actions. From a biomechanical standpoint, efficient energy transfer requires both appropriate stiffness modulation at the torso and controlled dissipation at the wrist and forearm to avoid premature energy loss or injurious peak loads.

Temporal sequencing is characterized by narrow, phase-specific windows in which muscle activation patterns and joint moments must be synchronized to exploit the stretch-shortening cycle and elastic recoil of passive tissues. Key timing markers include the transition from backswing to downswing,the moment of maximal pelvis-thorax separation,and the wrist-cocking-to-release interval. Training strategies should therefore emphasize neuromuscular timing as much as strength: motor control, rate of force advancement (RFD), and intersegmental coordination are primary targets. Recommended practice elements include:

- Segmental sequencing drills (e.g., slow-motion kinematic chaining with focus on pelvis lead).

- Reactive plyometrics timed to swing cadence to enhance SSC utilization.

- Unilateral stability and anti-rotation exercises to preserve separation angle under load.

- Deceleration and eccentric control training to protect the wrist and elbow during release.

- Video-based temporal feedback with frame-by-frame cueing to refine onset times of key segments.

| Phase | Primary contributor | Critical timing window |

|---|---|---|

| Backswing | Pelvis rotation & torso loading | Initiation to peak separation |

| Transition | Hip drive & eccentric trunk control | ~60-120 ms window pre-downswing |

| Downswing | Thorax-to-arm acceleration | Pelvis peak → thorax peak → arm peak |

| Impact/Release | Wrist impulse & hand speed | Last 30-50 ms before impact |

optimizing transfer efficiency requires addressing both technique and tissue capacity. Common sequencing faults-early release, casting, and insufficient pelvic lead-reduce clubhead velocity and increase compensatory loads at the distal joints. Implement progressive, measurable training programs that combine: (1) objective metrics (peak rotational velocity, separation angle, GRF impulses); (2) targeted strength/power work for RFD and eccentric control; and (3) contextualized swing drills with immediate temporal feedback. These integrated interventions improve mechanical output while reducing cumulative injury risk by ensuring that energy is transferred through the intended kinematic chain rather than offloaded to vulnerable structures.

Muscle activation Patterns and Neuromuscular Coordination: EMG Insights and Strengthening protocols for Enhanced Stability

Surface and intramuscular EMG investigations consistently reveal a temporally sequenced activation pattern in proficient golfers: early preparatory activity in the hip and trunk stabilizers is followed by rapid, phasic recruitment of the obliques, thoracic extensors and rotator cuff musculature during downswing and impact. This proximal-to-distal cascade optimizes transfer of angular momentum and minimizes energy leaks; deviations from this timing-such as delayed gluteal onset or excessive lumbar erector dominance-are associated with reduced clubhead speed and greater mechanical stress on the lumbar and shoulder joints. Quantitative EMG metrics (onset latency, peak amplitude, and integrated EMG) therefore provide objective markers to distinguish efficient from compensatory motor patterns and to monitor adaptation across training phases.

neuromuscular coordination emphasizes both selective activation and strategic co-contraction to preserve segmental alignment under high rotational loads. EMG profiles highlight the role of anticipatory postural adjustments: pre-impact increases in deep abdominal and hip-abductor activity stabilize the pelvis and lower spine, enabling more effective distal acceleration. Training should target these qualities through exercises that enhance feedforward control and intermuscular timing. Key training focuses include:

- Core feedforward activation – timed bracing drills emphasizing rapid onsets.

- Hip-lateral stability – single-leg loaded holds and dynamic balance tasks.

- Scapular and rotator cuff endurance – low-load, high-repetition control work.

- Reactive rotational control – perturbation-based med-ball and elastic-band progressions.

Strengthening protocols should be evidence-informed, progressive, and specific to the temporal demands exposed by EMG. A practical framework integrates isometric stabilization, eccentric control, and ballistic rotational power in sequenced phases: (1) motor-control acquisition with low-load isometrics and tempoed eccentric work, (2) strength and hypertrophy with multi-planar resisted loading, and (3) power and transfer with high-velocity, sport-specific throws and resisted swings.The following concise table maps representative targets and EMG-related cues to simple exercises for field submission:

| Target | Exercise | EMG Cue |

|---|---|---|

| Hip abductors | Single-leg banded stances | Early glute med onset |

| Deep abdominals | Timed plank bracing | Pre-rotation activation |

| Rotator cuff | Light external rotation sets | Low-amplitude sustained EMG |

Translating neuromuscular targets into practice requires periodized integration: include brief neuromotor warm-up sets (2-4 min) before on-course sessions, allocate dedicated 20-40 minute sessions for progressive stability work 2-3×/week, and reserve power-transfer drills for later phases as control improves. Use objective feedback where possible-timing windows from wearable EMG, inertial sensors for trunk rotation velocity, or video-to reinforce correct sequencing. Clinically, prioritize reduction of aberrant co-contraction patterns and asymmetries to lower injury risk; from a motor-learning perspective, emphasize variability of practice, external focus cues, and faded feedback to consolidate robust, context-specific motor programs that manifest as improved stability and more efficient force transfer in competitive swings.

Ground reaction Forces and Lower Limb Biomechanics: Optimizing Weight Transfer and Balance Through Footwork and Mobility

Efficient transfer of force from the feet into the ground and back into the kinetic chain is a primary determinant of swing power and consistency. The vertical and shear components of the ground reaction force (GRF) vector, together with the time‑resolved location of the centre of pressure (CoP), determine the resultant moment applied through the pelvis into the torso. Precise timing – a rapid rear‑to‑front shift of resultant GRF during transition and downswing – amplifies angular velocity of the hips and shoulder girdle; conversely, delayed or diffuse force application reduces peak clubhead speed and increases compensatory lumbar loading.Instrumented assessments (force plates, plantar pressure mapping) quantify peak GRF, impulse and CoP trajectory and thus provide objective targets for technique refinement.

Lower limb kinematics and neuromuscular activation underpin the patterns of GRF observed during the swing. The trail limb typically undergoes controlled eccentric knee flexion and hip external rotation to load elastic tissues, followed by a concentric drive that contributes to pelvis rotation. The lead limb functions primarily as a decelerator and load‑bearing brace, absorbing shear forces via knee extension and hip stability. Restricted ankle dorsiflexion or limited hip internal rotation commonly shifts workload proximally, elevating compressive and torsional forces at the lumbar spine and hip; restoring joint available motion and intermuscular coordination reduces injurious load transfer and improves mechanical efficiency.

Practical optimization emphasizes targeted mobility, strength and proprioceptive interventions combined with footwork cues that shape desirable GRF profiles. Key components include:

- Mobility: progressive ankle dorsiflexion and hip rotation routines to permit appropriate tibial and pelvic excursions.

- Load sequencing drills: split‑stance and med ball rotational throws that emphasize rear‑to‑front impulse timing.

- Balance and reactive control: single‑leg perturbation and unstable‑surface training to reduce CoP excursion and improve bracing on the lead leg.

- Instrumented feedback: short force‑plate sessions or in‑shoe sensors to convert subjective cues into objective metrics.

- Proximal-to-distal sequencing – initiate downswing with lower body/pelvis to generate ground reaction forces then transfer energy up the chain.

- Thoracic mobility drills – maintain or restore upper spine rotation to offload the lumbar segments.

- Hip mobility & stability training – enhance pelvic rotation capacity so lumbar rotation is not recruited excessively.

- Dynamic core control - eccentric and isometric trunk work that allows controlled dissipation of rotational inertia while resisting unwanted shear.

- Face awareness drills: mirror-impact and short-game gating to train consistent face angle at contact.

- Path-control exercises: alignment rods and swing-plane constraints to reduce excessive out-to-in or in-to-out deviations.

- Release-timing cues: delayed wrist unhinge and weighted-club drills to increase controlled lag and reduce early flip.

- Loft and shaft lean manipulation: address impact loft via posture and ball position adjustments to tune launch angle and spin rate.

- progressive lead‑hip strength and gluteus maximus recruitment exercises,

- anti‑rotation and chopped/woodchop progressions to improve segmental sequencing,

- load transfer drills (step and linear‑to‑rotational transitions) to normalize center‑of‑mass displacement).

- Peak clubhead speed and attack-angle variability

- Pelvis-to-shoulder separation and X-factor velocity

- Ground reaction force timing and medial-lateral load transfer

- EMG onset latencies for gluteus maximus,obliques,and erector spinae

- Set athlete-specific thresholds for progression and red-flag criteria for intervention;

- Embed short-form assessments (e.g.,60s IMU swing battery) into weekly practice;

- Use objective feedback windows (immediate biofeedback for motor learning; aggregated metrics for trend analysis).

- Grip mechanics: Neutral-to-slight-strong for reliable clubface control; grip pressure should be firm but not tense (4-6/10 scale).

- Stance & posture: Athletic,hip-hinge with slight knee flex; spine tilt aligned to desired ball flight and club selection.

- Backswing: Rotate around a stable spine angle; maintain width and a controlled wrist set to preserve swing radius.

- Transition: Smooth weight shift to the front foot with initiation from the lower body (hips) to start the downswing.

- Impact: Forward shaft lean (for irons), center-ish contact, and stable lower body to allow energy transfer.

- Follow-through: Balanced finish where the body faces the target-evidence of a well-sequenced swing and good balance.

- Launch monitors: Measure clubhead speed, ball speed, launch angle, spin rate, smash factor and carry distance.

- Video analysis & high-speed cameras: Frame-by-frame review of sequencing,spine angle,arm position and impact alignment.

- Inertial sensors & IMUs: Track segmental angular velocity and timing for kinematic sequencing feedback.

- Force plates: Quantify ground reaction forces and center-of-pressure movement during the swing.

- 3D motion capture: Gold standard for detailed joint kinematics and kinetics (usually used in research and high-performance settings).

- Weeks 1-2: Mobility & stability (30-45 min sessions, 3x/week). Focus on thoracic rotation, hip internal/external rotation and ankle mobility.

- Weeks 3-4: Movement patterning (3x/week). Add step drill, pause-at-top, slow-motion reps with impact tape or launch monitor feedback.

- weeks 5-6: Power development (2-3x/week). Medicine-ball throws, plyometrics and heavier slow swings with intent for speed.

- Weeks 7-8: Integration (3x/week). Full swings on the range, mixed clubs, and short-game integration with video & launch monitor checks.

- Clubhead speed: Primary driver of distance; small increases can yield large carry gains.

- Smash factor (ball speed ÷ clubhead speed): Indicator of efficient energy transfer.

- Consistency of attack angle and impact location: Repeats determine accuracy and spin control.

- Dispersion (left/right and overall): Key for shot-making and scoring.

- Excessive early hip rotation leading to early release.

- Strong grip but unstable weight transfer (reverse pivot moments).

- Paused-top drill and step-drill to re-sequence hips-first.

- Medicine-ball throws to teach rotational power and timing.

- Launch monitor sessions to dial in attack angle and smash factor.

- Balance mobility with stability-more rotation without core and hip control increases injury risk.

- Address asymmetries (leg/hip strength differences) with unilateral strength work.

- If you feel acute pain (particularly in low back or lead shoulder), stop and consult a medical professional-do not push through sharp pain.

- Use keywords naturally: “golf swing biomechanics”,”golf swing analysis”,”improve clubhead speed”,”hip-shoulder separation”,”kinematic sequence” and “ground reaction force”.

- Include measurable outcomes and metrics (e.g., clubhead speed, launch angle) to attract searchers looking for performance improvements.

- Add imagery and short video clips showing drills and before/after swings-multimedia increases engagement and time-on-page.

- Offer downloadable checklists (swing checklist, drill progressions) to capture email subscribers and improve dwell time.

- Prioritize hip-led initiation and a clean kinematic sequence (hips → torso → arms → club).

- Use ground reaction forces-feel the push into the ground-to generate rotational power.

- Track objective metrics (clubhead speed, ball speed, smash factor, launch angle) while practicing drills.

- Balance mobility work with strength and power training for durable improvements.

- Use video and launch monitor feedback frequently to link sensation to measurable outcomes.

These interventions should be periodized within the player’s training cycle and matched to on‑course demands to avoid acute overload.

Assessment targets and progression can be summarized with simple, actionable metrics for coaching and rehabilitation. The table below provides exemplar markers (relative, sport‑specific) that guide training priorities and return‑to‑play decisions.

| metric | Practical Target / Interpretation |

|---|---|

| Peak vertical GRF | ~1.1-1.6× body weight during downswing (higher indicates effective push‑off) |

| CoP lateral shift timing | Rear→front shift completed before maximal pelvis rotation |

| Ankle dorsiflexion ROM | Symmetric, functional range for controlled tibial progression |

| Lead‑leg peak shear | Moderate magnitude with good knee/hip control; excessive shear = technique compensations |

Spinal Mechanics, Pelvic Rotation, and Trunk Control: Strategies to Maximize Clubhead Speed While Minimizing Lumbar Stress

efficient force transfer in the golf swing depends on preserving the structural integrity of the lumbar spine while exploiting rotational mobility above and below it. The lumbar segments are anatomically optimized for sagittal flexion/extension and load-bearing rather than large axial rotations; excessive lumbar twist increases shear and compressive loads on intervertebral discs and facet joints. From a neuroanatomic perspective, the spinal cord and dural structures terminate and taper in the lower lumbar region, making neural elements potentially vulnerable to canal compromise in pre-existing conditions (e.g., lumbar stenosis). Maintaining a balanced lumbar lordosis and emphasizing thoracic rotation reduces harmful torsional loading at the lower spine while sustaining a kinematic chain that supports clubhead velocity.

Maximizing angular velocity at the clubhead requires strategic partitioning of rotation between pelvis, thorax and lower limbs. Rather than forcing large lumbar rotation, elite swings typically distribute motion: greater axial rotation in the thoracic spine and increased transverse rotation at the hips and pelvis, with the lumbar spine acting as a controlled, low-amplitude transmission link. Practical objectives include: preserving thoracic mobility,promoting hip-driven pelvic turn,and controlling lumbar axial displacement. The following compact reference summarizes commonly targeted rotational emphases used in performance and clinical literature (individualization required).

| Parameter | Practical target (qualitative) |

|---|---|

| Pelvic axial turn (backswing → impact) | Moderate to high - driven by hip external rotation and posterior chain activation |

| Thoracic rotation | High – primary source of rotational amplitude and speed |

| Lumbar rotation | Low – controlled coupling and stiffness to protect structures |

Implementation focuses on sequencing, neuromuscular control and targeted conditioning.Key strategies include:

Clinically, any history or signs of neurogenic claudication, progressive leg numbness/weakness, or activity-limiting back pain should prompt further evaluation for conditions such as lumbar spinal stenosis; referral to spine-specialized clinicians is prudent before implementing high-velocity rotational training. Prioritizing segmental distribution of rotation and graded conditioning optimizes clubhead speed while minimizing lumbar stress.

Club Kinematics and Release Mechanics: technical Adjustments to Improve Accuracy and Ball Flight Characteristics

Precise modulation of clubhead kinematics-encompassing the instantaneous **clubhead speed vector**,trajectory of the swing arc,and the rotational velocity about the shaft axis-determines the initial conditions at impact that govern carry,spin and dispersion.Small variations in **face angle** (±1-3°) or effective **dynamic loft** at contact produce disproportionately large changes in lateral deviation and spin axis tilt; therefore, kinematic analysis must resolve both translational and rotational components of the clubhead in the 0.02-0.05 s window surrounding impact. High-speed motion capture and synchronized launch-monitor data reveal that the vector sum of tangential and radial velocities at the head, combined with the moment of inertia distribution of the club, predict ball spin-rate and side-spin polarity more reliably than clubhead speed alone.

Release mechanics are the primary neuromuscular control that convert proximal sequencing into distal club-face orientation. The coordinated timing of wrist unhinge, forearm pronation/supination and lead-hip rotation controls the release point and the amount of residual **lag** retained into impact. A late, controlled release tends to promote a square face and reduced sidespin when paired with an in-to-out path, whereas an early or uncoupled release increases variability by amplifying small path-face mismatches. Quantifying release timing as the phase angle between torso rotation and clubhead angular velocity provides a repeatable metric for coaching and for setting objective training thresholds.

Technical adjustments aimed at improving accuracy and desired ball flight should target the kinematic variables that most strongly influence the impact window.Effective, evidence-based interventions include:

each intervention should be validated with post-drill kinematic snapshots and launch data to confirm the intended change in ball-flight parameters.

Below is a concise mapping of common adjustments to expected ball-flight outcomes; use this table as a reference when designing incremental practice protocols (wp-block-table is-style-stripes class shown for WordPress compatibility):

| Adjustment | Primary Flight Effect |

|---|---|

| Delayed release (increase lag) | Lower spin, tighter dispersion |

| Neutralize face at impact | Reduced side-spin, straighter shots |

| Path correction to square | Consistent draw/fade control |

| Shaft lean forward | Lower launch, less backspin |

Objective monitoring-using motion capture phase-angle metrics, shaft deflection sensors and launch monitors-enables precise quantification of these adjustments and supports an iterative, data-driven training program that aligns kinematic change with measurable improvements in accuracy and ball flight.

Common Swing Faults and Biomechanical Causes: diagnostic Tests and Evidence Based Corrective Interventions

Clinical diagnostic reasoning links observable swing faults to specific biomechanical impairments through a combined movement-screening and instrumented assessment strategy. Standardized tests used in practice include: Thoracic Rotation Test (seated/standing), Hip Internal Rotation ROM (prone goniometry), Single‑Leg Balance and Hops, Gluteal Strength Test (resisted abduction or single‑leg squat), and dynamic assessments such as the Overhead Squat and TPI Screening. Instrumented measures-3D motion capture, force‑plate ground reaction profiling and launch monitor club‑path/face‑angle metrics-provide objective kinematic and kinetic correlates to the clinical screen. Use of these complementary measures generates an evidence‑based impairment list (mobility, stability, sequencing, strength, symmetry) that directs targeted interventions.

Common positional faults often share predictable biomechanical causes and therefore reproducible corrective pathways.For example: early extension frequently indicates restricted hip flexion or poor eccentric hip‑extensor control; reverse spine angle implies a loss of thoracic extension/rotation or overuse of lumbar extension; and an over‑the‑top (outside‑in) path commonly stems from limited lead hip internal rotation or an early lateral shift. Diagnostic mapping is summarized below for quick clinical use:

| Fault | Key Diagnostic Test | Primary Corrective Intervention |

|---|---|---|

| Early extension | Prone hip flexion ROM; single‑leg hinge video | Hip hinge drills; eccentric glute loading |

| Reverse spine angle | Thoracic rotation/extension test | Thoracic mobility + anti‑extension core |

| Over‑the‑top | Lead hip IR ROM; launch monitor path | Lead hip mobilization + sequencing drills |

Faults associated with poor energy transfer-such as casting,scooping,or inadequate weight shift-reflect neuromuscular sequencing deficits rather than purely technical shortcomings. Diagnostic emphasis should target: timing (video frame‑by‑frame), force application symmetry (force plate), and rotational stiffness (passive/active ROM). Evidence‑based corrective strategies include:

These interventions should be prescribed with dose and progression principles drawn from strength‑and‑conditioning literature (volume, intensity, specificity).

To reduce injury risk while enhancing performance, apply an objective reassessment framework: baseline and follow‑up metrics should include clubhead speed, pelvis‑thorax separation angle, hip IR ROM, single‑leg hop symmetry and patient‑reported pain/function scores. Evidence supports multimodal correction-manual therapy for mobility deficits,progressive resistance training for force production,and motor‑control drills for sequencing-over isolated technical cueing. Recommended monitoring and return‑to‑practice criteria emphasize measurable enhancement in the identified impairment(s) plus reproducible swing mechanics under fatigue and varied practice conditions. Individualized, periodized programs informed by repeated diagnostic testing maximize transfer and minimize recurrence of biomechanically driven faults.

Integrating Biomechanical Assessment into Coaching Practice: Objective Metrics, Technology Applications, and Periodized Training Plans

conceptual integration here denotes the purposeful process of making disparate assessment modalities cohere into a unified coaching workflow-i.e., to make the athlete’s biomechanical profile into a working whole.Objective metrics (kinematics, kinetics, temporal sequencing, and neuromuscular activation) are translated into actionable coaching cues by mapping each metric to a discrete performance or injury-risk outcome. Key objective metrics to prioritize include:

Modern practice requires targeted technology applications that provide repeatable,valid measures while fitting the coaching environment. Deploy a tiered sensor architecture-high-fidelity 3D motion capture and force plates in lab settings; portable IMUs, pressure insoles, and video+analytics in the field-to support longitudinal monitoring and on-course coaching. The table below illustrates an exemplar sensor-to-metric mapping for pragmatic use in weekly cycles.

| Sensor | Primary Metric | Coaching Use |

|---|---|---|

| 3D motion capture | Segment angular velocities | Technique diagnosis, swing sequencing |

| Force plate | Peak vertical & horizontal GRF | Force transfer, balance strategy |

| EMG / IMU | Muscle timing & trunk rotation | Neuromuscular programming |

Translate assessment outputs into periodized training plans that move from diagnostic to preparatory to performance phases, each with explicit biomechanical targets and monitoring rules. Typical periodization blocks include: Baseline Assessment (establish normative baselines and asymmetries), Capacity Development (strength, power, hip mobility), Transfer & Motor Control (speed-specific drills and sensorimotor integration), and Peaking & Maintenance (load tapering, precision practice). Practical implementation steps for coaches:

Q&A

Note on search results: the provided web search results relate to contemporary political/business news (Cracker barrel/Trump) and do not contain material relevant to biomechanics or golf. The following Q&A is generated to address the topic “Biomechanical Analysis and Optimization of the Golf Swing” in an academic, professional style and does not rely on those unrelated results. For the original article,see: https://golflessonschannel.com/biomechanics-and-optimization-of-the-golf-swing/

Q1. What is the primary aim of a biomechanical analysis of the golf swing?

A1.The primary aim is to quantify the kinematic and kinetic determinants of swing performance and injury risk-specifically to (a) identify movement patterns and coordination strategies that maximize clubhead and ball speed while maintaining accuracy, and (b) elucidate mechanical loads on tissues to inform injury-prevention and training interventions.

Q2. Which outcome measures are most relevant for evaluating performance in a golf-swing biomechanics study?

A2. Key performance measures include clubhead speed, ball speed, smash factor, launch angle, spin rate, carry distance, shot dispersion (accuracy), and temporal sequencing metrics such as peak velocity timings. Secondary biomechanical outcomes include joint angles, angular velocities, joint moments and powers, ground reaction forces, and muscle activation timing/intensity.

Q3. What instrumentation is commonly used to collect biomechanical data on the golf swing?

A3. Typical instrumentation includes 3‑D optical motion capture systems (marker-based or markerless), high‑speed video, force plates (to record ground reaction forces and center-of-pressure), electromyography (EMG) for muscle activity, instrumented clubs or club-head sensors, launch monitors (Doppler/photometric) for ball metrics, and, increasingly, wearable IMUs for field-based assessment.Q4. what kinematic features characterize an efficient golf swing?

A4. Efficient swings commonly display a coordinated proximal-to-distal sequencing (pelvis → trunk → upper arm → forearm → club), an early and well-timed weight transfer, a pronounced X‑factor (differential between pelvis and trunk rotation) during the backswing and early downswing, smooth acceleration through the hitting zone, and optimized clubface orientation at impact.

Q5. How is the proximal‑to‑distal sequence quantified and why is it meaningful?

A5. The sequence is quantified by measuring the timing of peak angular velocities of successive segments (pelvis, trunk, shoulder, elbow, wrist, club). It is important because proper sequencing maximizes energy transfer between segments (reducing intersegmental energy loss) and optimizes clubhead speed with lower muscular effort and reduced joint loading.Q6. Which kinetic analyses are essential for understanding force transfer during the swing?

A6. Essential analyses include inverse dynamics to compute joint moments and powers, ground reaction force (GRF) analysis to quantify vertical and horizontal force generation and weight shift, and computation of intersegmental power flow to determine how mechanical energy is produced and transmitted through the kinetic chain.

Q7. What typical muscle activation patterns (from EMG) are observed in skilled golfers?

A7. Skilled golfers show anticipatory activation of trunk stabilizers and hip musculature during the backswing, phasic activations of trunk rotators and extensors during downswing, and rapid, high‑frequency activations of distal musculature (forearm/wrist) near impact. Timing is consistent with the proximal‑to‑distal sequencing and tends to be more reproducible in skilled players.

Q8. How do biomechanics inform injury-risk assessment in golfers?

A8. Biomechanical metrics-such as high lumbar shear/compression forces, large peak trunk rotation velocities with limited hip rotation, excessive wrist extension/flexion at impact, and repeated high‑magnitude eccentric loads-are associated with increased risk of low back, wrist, elbow, and shoulder injury. identifying maladaptive movement patterns allows targeted corrective strategies.

Q9. what role does the X‑factor play, and are there tradeoffs?

A9. the X‑factor (torso-pelvis separation) generates elastic energy and contributes to higher clubhead speed. Tradeoffs include potential increases in lumbar torsional and shear loading if hip mobility or trunk stability is insufficient. Optimization seeks an X‑factor that enhances performance while minimizing harmful spinal loads.

Q10. Which statistical and computational methods are used to analyze biomechanical data in this context?

A10. Methods include time‑series analyses (e.g., statistical parametric mapping), repeated‑measures and mixed‑effects models, principal component analysis and other dimensionality‑reduction techniques, machine‑learning classifiers/regressors for performance prediction, inverse dynamics and musculoskeletal modeling for internal loading estimates, and optimal control/trajectory optimization for theoretical swing improvements.

Q11. How can musculoskeletal modeling contribute to optimization?

A11. Musculoskeletal models allow estimation of internal joint forces, muscle forces, and energy flows that cannot be measured directly. They can be used to simulate alterations in technique,predict effects of strength/adaptability changes,and drive optimization algorithms that identify movement patterns that maximize performance metrics under injury‑risk constraints.

Q12. What optimization approaches are used to propose improved swing mechanics?

A12. Approaches include constrained numerical optimization (e.g., optimal control), genetic algorithms and other evolutionary strategies, and data‑driven methods (e.g., supervised ML to map kinematics to performance). constraints typically include anatomical limits, task objectives (maximize clubhead speed, accuracy), and injury‑related thresholds.

Q13. How should studies be designed to ensure ecological validity?

A13. Include skilled and recreational golfers, use real clubs and balls and full swings where possible, integrate field‑based measures (wearables/IMUs, launch monitors) in addition to lab tools, allow warm‑up and familiarization, and if feasible record on-course shots.Report contextual factors (fatigue, surface, ball type) that may influence mechanics.

Q14. What are common sources of measurement error and how can they be mitigated?

A14.Errors arise from soft tissue artifact (marker movement relative to bone), synchronization mismatches (among cameras, force plates, EMG), sensor drift (IMUs), and launch‑monitor measurement limitations. Mitigation strategies include multi‑segment marker sets, filtering and signal‑processing best practices, cross‑validation with autonomous measures, and rigorous calibration procedures.

Q15.What training interventions have biomechanical rationale for improving swing performance?

A15.Interventions include mobility training (hip, thoracic spine, shoulder), targeted strength and power development (hip extensors, trunk rotators, posterior chain, forearm muscles), plyometric and ballistic training for rate of force development, neuromuscular timing drills to reinforce sequencing, and technique coaching informed by objective biomechanical feedback.

Q16. How can coaches apply biomechanical findings without extensive lab equipment?

A16. Coaches can use practical proxies: monitor weight‑shift and center of pressure by observing foot pressure and balance, assess pelvis-trunk separation with video (sagittal and frontal planes), use simple timing drills to enhance sequencing, employ affordable launch monitors for ball metrics, and integrate mobility/strength screens to identify physical limitations.Q17. What are the principal limitations of current biomechanical research on the golf swing?

A17. Limitations include small sample sizes, overreliance on elite or novice extremes rather than representative populations, lab constraints limiting ecological validity, cross‑sectional designs that cannot establish causality, variability in data-processing protocols, and incomplete integration of neuromuscular, cognitive, and environmental factors.

Q18.How is skill level accounted for in analyses and interpretation?

A18. analyses should stratify or control for skill (e.g., handicap, clubhead speed, years of experiance). Skill moderates kinematic variability, timing, and robustness of movement patterns; thus, findings from elite cohorts may not generalize to recreational players. Longitudinal designs help determine whether observed patterns are causes or consequences of skill.

Q19. What precautions are recommended when interpreting correlations between mechanics and performance?

A19. Correlation does not imply causation: observed associations may reflect compensatory strategies, confounding physical attributes (strength, flexibility), or equipment effects.Robust inference requires longitudinal or intervention studies, biomechanical modeling to test causality, and sensitivity analyses controlling for potential confounders.

Q20. How can biomechanics inform individualized training plans?

A20. By identifying a player’s specific kinematic deficits (e.g., limited hip rotation), strength imbalances, or maladaptive sequencing, practitioners can prescribe targeted mobility, strength, and technique interventions. Musculoskeletal models or data-driven predictions can estimate the expected performance gain and injury-risk tradeoff for proposed changes.

Q21. What role do wearables and real‑time feedback play in optimization?

A21. Wearables (imus, pressure insoles, smart grips) enable longitudinal, field‑based monitoring of swing metrics and load exposure. Real‑time auditory or haptic feedback can accelerate motor learning by highlighting timing or sequencing errors. However, algorithms must be validated against gold‑standard measurements to ensure reliability.

Q22. How should injury‑prevention programs be structured for golfers based on biomechanical evidence?

A22. Programs should combine screening (mobility, strength, movement quality), corrective exercise (hip/thoracic mobility, lumbar stability), progressive load management (avoiding abrupt increases in swing volume/intensity), and technique modifications to redistribute harmful loads. Education on recovery and ergonomics (e.g., warm‑up, swing volume limits) is essential.

Q23. What future research directions are most promising?

A23. Promising directions include integration of machine learning with large, longitudinal datasets for individualized prediction; improved markerless motion capture and wearable validation for on‑course biomechanics; subject‑specific musculoskeletal models; coupling neuromuscular control models with optimization frameworks; and randomized controlled trials of biomechanics‑informed interventions.

Q24. How should researchers report findings to maximize reproducibility and clinical utility?

A24. Report participant characteristics (age, sex, handicap), equipment and calibration details, marker/sensor placement protocols, signal‑processing steps (filter types/cutoffs), definitions of temporal events (e.g., impact), statistical methods including effect sizes, and share anonymized datasets and code where feasible.Discuss practical implications and limitations candidly.

Q25. What succinct practical recommendations emerge from biomechanical analyses for players seeking to improve distance and reduce injury risk?

A25.prioritize hip and thoracic mobility to permit safe trunk-pelvis separation; develop lower‑body power and trunk rotational strength to support proximal energy generation; train sequencing via drills emphasizing pelvis rotation initiation and delayed hand release; monitor and limit excessive lateral trunk bending and abrupt lumbar twisting; use objective ball and club metrics to track progress; and integrate structured warm‑up and recovery routines.

If you would like,I can (a) draft a concise executive summary of the article targeted to coaches and practitioners,(b) produce a methods checklist for conducting a laboratory golf‑swing study,or (c) convert these Q&A items into a format suitable for supplementary material in a manuscript. Which would you prefer?

this review synthesizes current knowledge on the kinematic, kinetic, and neuromuscular determinants of an effective and safe golf swing, emphasizing the centrality of coordinated proximal-to-distal sequencing, optimized pelvis-thorax separation, timely muscle activation patterns, and effective ground reaction force generation and transfer. Biomechanical assessment tools (motion capture, EMG, force platforms, and musculoskeletal modeling) have clarified how subtle variations in joint timing, segmental rotations, and rate of force development influence clubhead speed, shot consistency, and tissue loading. Together, these findings identify mechanistic targets for technique refinement and injury risk mitigation.

Translating biomechanical insight into practice requires individualized,evidence-informed interventions. Coaching strategies that prioritize intersegmental timing and coordinated sequencing, strength and power programs that enhance rotational force production and rate of torque development, and mobility and motor-control exercises that preserve safe ranges of motion can all contribute to performance gains while reducing overload. Objective monitoring-through laboratory assessment or validated wearable technologies-enables progressive, measurable training and can help distinguish effective adaptations from compensatory patterns that elevate injury risk.

despite advances, important gaps remain. Much of the literature is cross-sectional or based on highly controlled laboratory swings that may not fully capture on-course variability. Future work should expand longitudinal and ecologically valid studies across sex,age,and skill levels; integrate markerless capture,machine learning,and subject-specific musculoskeletal models; and couple performance metrics with direct measures of tissue stress to better predict injury.greater interdisciplinary collaboration among biomechanists,clinicians,coaches,and sports scientists will be essential to refine models of swing mechanics and to translate them into scalable,athlete-centered interventions.

By combining rigorous biomechanical analysis with targeted training and ongoing evaluation,practitioners can more reliably optimize swing mechanics for both performance and long-term musculoskeletal health. Continued research and cross-disciplinary knowledge exchange will accelerate the development of practical,evidence-based approaches that respect individual variability while advancing the scientific foundations of golf performance.

Biomechanical Analysis and Optimization of the Golf Swing

Note: the web search results provided with this request did not include golf-related sources, so the following article is composed from established biomechanical and coaching principles and practical, evidence-aligned training methods.

Why biomechanics matters for your golf swing

Understanding swing biomechanics turns guesswork into measurable progress. Biomechanical analysis helps you identify the sequence, timing, and forces that produce high clubhead speed, consistent impact, and reliable ball flight.Instead of tinkering with feel-only cues, a biomechanical approach links what you feel to objective outcomes-launch angle, ball speed, spin, and dispersion.

Core biomechanical principles of an optimized golf swing

Kinematic sequence

The kinematic sequence describes how the body segments accelerate during the downswing: hips → torso → lead arm → club. A correct sequence maximizes energy transfer to the clubhead while minimizing compensatory movements that steal speed and consistency.

Ground reaction force (GRF)

GRF is the push against the ground that creates torque and accelerates the body through the swing. Efficient golfers use a timed lateral-to-vertical force shift (weight transfer) that supports rotation without losing balance.

Hip-shoulder separation (X-factor)

The separation between pelvis rotation and upper torso rotation stores elastic energy in the torso. Greater, controlled separation often increases rotational power, but it needs to be matched with mobility and stability to avoid injury.

Angular velocity and timing

peak angular velocities (hips,torso,arms,club) and their timing are crucial. Maximum clubhead speed occurs when distal segments (hands/club) reach peak velocity after proximal segments (hips/torso) have begun decelerating-this is the essence of an efficient kinematic sequence.

Key swing components – biomechanical checklist

Common biomechanical faults, causes and fixes

| Fault | Biomechanical cause | Speedy correction |

|---|---|---|

| Early release | Poor wrist/body sequencing | Throw-away-the-handle drill; pause at transition |

| Over-sway on backswing | Excess lateral weight shift, weak core | Feet-together backswing; feel coiling, not sliding |

| reverse pivot | Improper weight shift; upper-body dominant | Slow-motion swings focusing on hip turn first |

| Slice | Open clubface at impact; out-to-in swing path | Grip/face control drills; path drill (gate) |

How to measure swing biomechanics (tools & metrics)

practical training drills to improve biomechanics

1. Hip-led transition (step drill)

Begin with your normal address. On the takeaway, step the front foot back to stance and feel the hips rotate first on the downswing. This encourages hip initiation and correct weight transfer.

2. Pause at the top

Take slow swings, pause for one second at the top of the backswing, then start the downswing with the hips. This helps establish the kinematic sequence and eliminates early arm dump.

3. Medicine-ball rotational throw

Perform rotational throws (short distance) to train explosive hip-to-torso transfer. use throws to the target and off-angle to simulate different lies.

4. Mirror & feedback routine

Use a mirror or recording device; practice achieving a consistent spine angle, wrist set, and alignment. Combine with launch monitor stats to correlate feel with numbers.

5. Ground force timing drill

From address, slowly shift to the back foot during the backswing and explosively load the front foot through the downswing-feel the push into the ground and rotate.

Sample 8-week practice block for biomechanical advancement

Goal: Improve kinematic sequence, add 3-6 mph clubhead speed, and tighten dispersion.

Translating biomechanics into on-course performance

Metrics to monitor as you train:

Case study (applied biomechanical correction)

Player profile: Amateur male, ~95 mph driver speed, persistent pull-hook and inconsistent distance.

Assessment findings:

Intervention:

Outcome (8 weeks): Clubhead speed improved to 100 mph, smash factor rose by 0.05, dispersion narrowed, and ball flight corrected from pull-hook to controlled draw. The player reported improved confidence and less physical fatigue.

injury prevention and recovery considerations

SEO-focused tips for coaches and content creators

Frequently asked questions (FAQ)

Q: Will improving biomechanics always add distance?

A: Not always-distance gains depend on mobility, strength, sequencing and impact consistency. Proper biomechanics create the potential for distance, but it must be paired with speed training and impact optimization.

Q: How often should I record video for analysis?

A: Record a baseline, then every 2-4 weeks during a focused training block or whenever you feel a swing change. Short clips from face-on and down-the-line angles are most useful.

Q: Can beginners use biomechanical training?

A: Yes. For beginners, emphasis should be on movement quality, posture, balance and simple sequencing-complex metrics are more relevant as skill level increases.