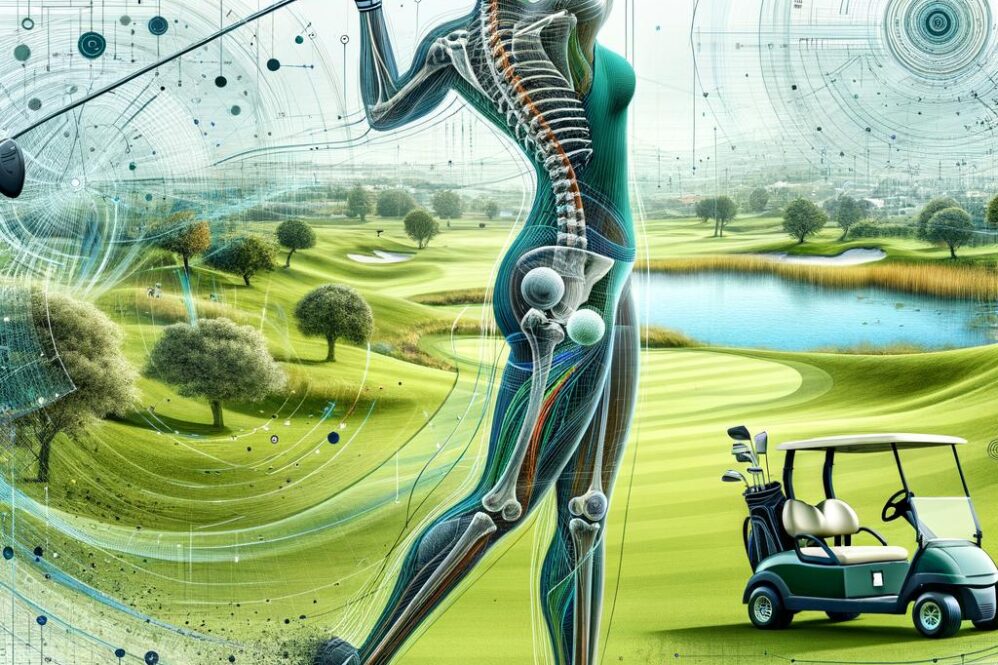

The golf swing is a complex, high‑velocity motor skill that exemplifies the submission of mechanical principles to human movement. Framed within the broader discipline of biomechanics-defined as the study of mechanical laws relating to living organisms-theoretical analysis of the golf swing draws on centuries of inquiry into motion, force, and structure to explain how coordinated segmental actions generate clubhead speed, direct the ball, and place tissue structures under load (see summaries in Physio‑Pedia and foundational reviews of the field) [1,2,3]. A rigorous theoretical treatment synthesizes kinematic descriptions, kinetic cause-effect relationships, and neuromuscular control strategies to reveal both the determinants of performance and the mechanisms of injury.

This article presents a theory‑driven review of golf‑swing biomechanics. Beginning from frist principles of rigid‑body mechanics and inverse dynamics, we examine how intersegmental sequencing, angular momentum transfer, and ground reaction forces underpin fast, repeatable strikes. We integrate these mechanical frameworks with neuromuscular concepts-motor program organization, timing of muscle activation, and the stretch‑shortening cycle-to explain how athletes transform muscular work into clubhead velocity while modulating accuracy and adaptability. Theoretical models are discussed alongside common measurement paradigms (three‑dimensional motion capture, force platforms, electromyography) to clarify the assumptions and limits of current inference.

An evidence‑based theoretical perspective also highlights trade‑offs that shape technique prescription and injury prevention. By mapping loads and motion patterns implicated in lumbar, shoulder, and elbow pathology, the review links mechanical determinants of high performance to tissue‑level risk factors and proposes biomechanically coherent strategies for technique refinement and conditioning. we identify conceptual and methodological gaps-such as the need for multiscale models that couple neuromuscular control with tissue mechanics and for ecologically valid assessments-thereby setting an agenda for future theoretical and empirical work that can more directly inform coaching, rehabilitation, and equipment design.

references

– Physio‑Pedia: biomechanics [1]

– Scholarly review: Biomechanics – historical and conceptual perspectives [2]

– Biomechanics overview: Wikipedia [3]

– Applied biomechanics educational summary [4]

Theoretical Foundations of Golf Swing Biomechanics: Principles of Kinematics and Kinetics

Theoretical frameworks in golf-swing biomechanics establish the conceptual distinction between motion descriptors and the causes that generate motion. In this context, kinematics denotes the geometric and temporal description of the swing (positions, velocities, accelerations), whereas kinetics addresses the forces and moments that produce those kinematic outcomes. This distinction echoes classical definitions of “theoretical” knowledge as concerned with general principles rather than immediate practice, providing a scaffolding for hypothesis-driven measurement and interpretation in applied coaching and research.

Kinematic principles emphasize sequencing, timing and intersegmental coordination. Critical measurable features include club- and segment-path geometry, angular velocities of pelvis, thorax and wrists, and timing of peak velocities that define the kinematic sequence. Empirical models predict that optimal energy transfer follows a proximal-to-distal pattern; deviations alter club-head speed and shot dispersion.

Key kinematic variables commonly measured in laboratory and field studies include:

- Pelvic rotation and tilt

- Thoracic rotation and X-factor (torso-pelvis separation)

- wrist **** and release timing

- Club-head linear and angular velocity

Kinetics and load transmission describe the forces and moments driving the swing: internal joint torques, external ground reaction forces (grfs), and interaction forces between club and ball. The following concise table links representative kinetic measures with units and practical implication:

| Measure | typical Unit | Practical relevance |

|---|---|---|

| Peak GRF | Newton (N) | Indicator of lower-limb drive |

| Hip torque | Newton·meter (N·m) | Rotational power source |

| Club-head impulse | Newton·second (N·s) | Ball exit velocity predictor |

Neuromuscular control and applied implications integrate motor-program organization,muscle activation timing,and reflex-mediated responses (e.g., stretch-shortening cycles). Coaching interventions should target reproducible timing of agonist bursts, robust proximal-to-distal sequencing, and conditioning that moderates peak joint loads. Evidence-based practice thus combines kinematic templates, kinetic load management and neuromuscular training to refine technique while mitigating injury risk through controlled progressive loading, variability-aware practice, and objective monitoring (e.g., wearable IMUs, force platforms).

Segmental Sequencing and Temporal Coordination: optimizing Proximal to Distal Transfer

Efficient transfer of mechanical energy through the body during the golf swing depends on orderly movement initiation from the larger, proximal segments toward the distal segments. this proximal-to-distal cascade minimizes energy dissipation and maximizes clubhead speed by exploiting intersegmental dynamics and the conservation of angular momentum.Biomechanically, optimal sequencing reduces counterproductive joint torques and allows the distal segments to act as end-effectors that amplify the kinetic contributions generated proximally.Precise temporal relationships between rotations, translations, and joint angular accelerations therefore underpin consistent, high-performance ball striking.

The empirical kinematic sequence commonly observed in skilled players progresses from pelvis rotation to thorax rotation, followed by upper-arm acceleration and finally rapid forearm and wrist pronation culminating in club release. Each segment attains its peak angular velocity in a reproducible order that is critical for constructive inertial transfer.Disruption of this order-such as premature arm acceleration or delayed trunk rotation-introduces negative work and increases variance in impact conditions. In research terms, the sequence is quantified by relative timing indices and cross-correlation of segmental angular velocity profiles.

Several temporal metrics are used to quantify sequencing and coordination in both lab and field settings; these provide objective targets for coaching and motor learning.Key markers include:

- Peak pelvis angular velocity – typically the first peak in the downswing sequence (ms relative to impact).

- Peak thorax angular velocity – follows pelvis peak and mediates trunk-to-arm transfer.

- Peak arm/forearm angular velocity – signals proximal energy arrival to the upper limb.

- Wrist release timing – final distal acceleration linked to clubhead speed and launch conditions.

Quantitative phase table (representative values for sequencing order and primary contributors):

| Phase | Primary contributor | Relative timing |

|---|---|---|

| Pelvis rotation | Hip extensors/rotators | Early downswing (lead) |

| Thorax rotation | Core musculature | Mid downswing |

| Arm acceleration | Shoulder and elbow dynamics | Late downswing |

| Wrist release | Forearm/wrist muscles | Just before impact |

Translating biomechanical principles into practice requires targeted drills and load-management strategies that prioritize neuromuscular timing over brute strength. Controlled variability, augmented feedback (e.g., video timing cues, wearable inertial sensors), and progression from slow to match-speed swings encourage the nervous system to refine intersegmental coordination. Emphasizing a single coaching cue-such as initiating downswing with the hips while maintaining relative trunk stability-can definitely help restore the correct kinematic order. Ultimately, combining objective temporal assessment with task-specific practice fosters durable improvements in temporal coordination and effective proximal-to-distal transfer.

Ground Reaction Forces and Torque Production: Strategies to Enhance Power and Stability

In the golf swing the forces exchanged at the feet are not incidental but foundational: vertical and horizontal components at the foot-ground interface create net vectors that generate moments about the athlete’s joints and about the body’s center of mass. These moments translate into angular acceleration of the pelvis and trunk and ultimately into clubhead velocity through a proximal‑to‑distal sequence. Conceptually, the body acts as a force transducer-the orientation, magnitude and timing of interface forces determine how effectively lower‑limb effort becomes rotational torque in the torso and upper extremity segments.

Effective torque production depends on controlled shifts in the center of pressure and timely redistribution of load between the trail and lead limbs. A rapid lateral push into the lead side produces a ground reaction impulse that creates a counter‑rotational moment, while a well‑timed vertical impulse can augment loft control and stability at impact. The kinetic‑chain principle is central: coordinated activation from hip rotators, core stabilizers and scapular muscles must be synchronized with ground‑directed impulses to maximize net work and minimize dissipation through unwanted motion.

Applied strategies fall into technique and practice design. Key interventions that coaches and players should prioritize include:

- Optimized stance and base: moderate width to allow frontal plane force generation without compromising rotational mobility.

- Bracing lead leg: isometric stiffness near impact to convert horizontal shear into rotational torque rather than allowing energy leakage.

- Sequenced weight transfer: train the temporal pattern of push from trail foot to lead foot to preserve proximal‑to‑distal timing.

- Reactive training: short‑duration plyometrics and medicine‑ball throws to enhance rapid force development and transfer.

Physical planning must support the mechanical aims. Strength and power programs should emphasize unilateral force production, hip external rotation strength, transverse‑plane explosiveness and reactive ankle/foot stiffness.The following concise table illustrates exercise selection mapped to their primary mechanical benefit:

| Exercise | Primary Benefit |

|---|---|

| Single‑leg hop | Reactive unilateral force |

| Medicine‑ball rotational throw | Transverse power transfer |

| Deadlift variant | Hip/torso torque capacity |

| Balance board drills | Proprioceptive stability |

measurement and feedback close the loop between strategy and outcome. Force‑plate metrics, plantar pressure mapping and inertial sensors provide objective indices of impulse timing, peak horizontal/vertical force and center‑of‑pressure migration-data that can be used to refine cues and progressions. Practical coaching cues that align with biomechanical measures (for example,”push the ground lateral‑forward early in downswing” paired with a target GRF profile) allow practitioners to translate laboratory constructs into on‑course performance improvements while preserving balance and injury risk management.

Musculoskeletal and neuromuscular Dynamics: Electromyographic Patterns and motor Control Recommendations

The golf swing is an integrated expression of the musculoskeletal system – bones, joints, muscles, tendons and ligaments – that must both generate and transmit rotational and translational forces with high temporal precision. Electromyographic (EMG) investigations consistently show phased, task-specific muscle activation rather than simultaneous maximal activation: anticipatory pre-activation of stabilizers, a proximal-to-distal power transfer, and finely graded agonist-antagonist coordination to optimize clubhead velocity while protecting joint structures. Understanding these neuromuscular dynamics reframes technique coaching: technique refinements should aim to improve intersegmental timing and muscle recruitment quality, not merely increase gross strength or range of motion.

EMG signatures across the macro-phases of the swing highlight reproducible patterns of activation that inform training priorities. Typical qualitative patterns are summarized below for clarity and translation to practice.

| Phase | primary EMG Features | Representative Muscles |

|---|---|---|

| Address → early backswing | Low-level tonic activation; preparatory co-contraction | Multifidus, glute medius, rotator cuff |

| Late backswing → transition | Increased stretch of hip/trunk rotators; eccentric control | Erector spinae, external oblique, glute max |

| Downswing → impact | Proximal-to-distal burst; high rate of force development | Glute max, adductors, obliques, forearm flexors |

| Follow-through | deceleration bursts; controlled eccentric activity | Hamstrings, posterior deltoid, scapular stabilizers |

From a motor-control perspective, training should prioritize timing, rate of force development (RFD), and feedforward stabilization in addition to conventional strength. Practical, evidence-aligned recommendations include:

- Motor-timing drills: short-sequence med-ball rotational throws emphasizing rhythm and proximal-to-distal sequencing.

- Reactive/perturbation work: resisted and unpredictable-recoil swings to enhance anticipatory muscle recruitment.

- RFD and power training: low-volume plyometrics and ballistic rotational medicine-ball exercises to raise the speed of force production without sacrificing control.

- Sensorimotor integration: single-leg balance with torso rotation, velocity-variable net swings, and video/EMG biofeedback where available.

These interventions should be periodized into technical, tempo and power blocks aligned with on-course practice.

Injury risk is tightly linked to maladaptive neuromuscular patterns: delayed activation of deep trunk stabilizers, excessive co-contraction in distal segments, and inter-limb asymmetries amplify load on passive tissues (discs, labrum, epicondylar tendons). Preventative strategies therefore target the same neuromuscular substrates that enhance performance: eccentric capacity of posterior chain, scapular stabilizer endurance, targeted rotator-cuff activation, and hip-centric strength and mobility. emphasize progressive eccentric loading,neuromuscular re-education (biofeedback,tempo constraints),and multimodal mobility-strength integration rather than isolated stretching alone.

Assessment and programming should be individualized and informed by both performance and injury metrics. Where available, surface EMG, motion-capture timing, and simple force-platform or pressure-mat tests can identify phase-specific deficits and asymmetries to guide intervention.Programmatically, integrate:

- objective diagnostics (timing/asymmetry indices),

- targeted neuromuscular drills early in sessions, and

- progressive loading toward power outputs that preserve coordination.

Monitor fatigue and on-course transfer; prioritize restoration of efficient activation patterns (feedforward stabilization, proximal sequencing, controlled deceleration) as the primary criterion for advancing technical load or competition exposure.

Spinal Loading, Pelvic Mechanics, and Injury Risk Reduction Strategies

The golf swing imposes complex multiplanar loads on the spinal column, combining axial compression, anterior-posterior shear, lateral bending, and high-magnitude torsion within fractions of a second. These loads concentrate across the lumbar motion segments where intervertebral discs,facet joints,and ligaments share force transmission; the vertebral column’s segmented architecture and intervertebral discs provide both mobility and load attenuation but render the lumbar region vulnerable to repetitive microtrauma. Peak compressive forces typically occur near ball impact as ground-reaction forces and angular velocities are transmitted up the kinetic chain; simultaneous high torsional velocity raises intradiscal pressure and increases risk of annular strain. Understanding the temporal coupling of force onset and rotational velocity is therefore central to quantifying spinal loading during swing cycles.

Efficient energy transfer relies on coordinated pelvic mechanics and a well-timed lumbopelvic rhythm. Pelvic rotation initiates kinematic sequencing by storing elastic energy in the hips and lumbar tissues and then releasing it as the pelvis decelerates and the torso accelerates-this proximal-to-distal sequence reduces excessive lumbar torsion when functioning correctly.Pelvic tilt (anterior/posterior) and lateral shift also alter lumbar lordosis and facet loading: early pelvic extension or excessive lateral flexion can offload hip contribution and force the lumbar spine to absorb rotational demand.Thus, maintaining adequate hip internal/external rotation, femoroacetabular mobility, and controlled pelvic translation is critical for safe force distribution.

Common injury patterns linked to swing mechanics include lumbar disc degeneration and herniation, facet joint arthropathy, sacroiliac joint dysfunction, and pars stress reactions in younger athletes. Risk factors are both intrinsic (age-related disc desiccation, prior lumbar pathology, asymmetrical strength or mobility) and extrinsic (high swing speed without adequate conditioning, repeated practice with compensatory kinematics, and poor equipment fit).Biomechanically, repeated cycles of high torsion combined with compressive loading-particularly when buffering capacity of anterior abdominal and paraspinal musculature is insufficient-accelerate tissue fatigue and microfailure. Objective screening for asymmetries in rotation, side-bending, and hip internal rotation can identify elevated risk before symptoms manifest.

Intervention strategies should integrate technique refinement, targeted conditioning, and load management to minimize cumulative spinal stress. Key tactical and clinical approaches include:

- Technique: emphasize pelvis-first sequencing,limit excessive lateral flexion and early extension,and promote a balanced weight-transfer pattern to decrease peak lumbar torsion.

- Neuromuscular training: progressive core stabilization with transverse abdominis and multifidus recruitment, hip rotator endurance, and reactive trunk control drills to improve anticipatory stabilization.

- Mobility and symmetry: corrective interventions for hip internal/external rotation deficits and thoracic rotation restrictions to restore distributed motion.

- Load management: moderate practice volume, periodized intensity, and equipment adjustments (shaft flex, grip size) to optimize force demands.

These strategies collectively reduce peak tissue strain and improve resilience to repetitive loading.

| Metric | Target/Observation | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Lumbar lateral flexion | <10° during downswing | Limits asymmetric compressive loading |

| Pelvic rotation range | 40-60° total | Promotes hip-driven sequencing |

| Trunk rotation velocity | Moderate peaks with smooth deceleration | Reduces abrupt torsional spikes |

objective monitoring of these parameters-using motion analysis, force-plate data, or targeted clinical tests-supports individualized interventions that reduce cumulative spinal loading and lower injury incidence in golfers.

Clubhead Speed, Energy Transfer Efficiency, and Equipment Considerations

Clubhead velocity is the primary mechanical input to ball speed and flight, governed by the summation of segmental angular velocities and translational motion generated by the golfer’s kinetic chain. Empirical and theoretical analyses show a near-linear relationship between peak clubhead speed and potential carry distance when launch conditions are controlled; however, this relationship is mediated by impact quality and the relative contributions of axial rotation, lateral weight shift, and wrist uncocking. In biomechanical terms, maximizing clubhead velocity requires efficient conversion of proximal segmental momentum into distal segmental velocity while minimizing counterproductive energy leaks-thus the terms proximal-to-distal sequencing and temporal coordination are central to any quantitative model of swing speed.

Efficiency of energy transfer at impact is characterized by both the mechanical interaction between club and ball and the effective mass of the system at the moment of contact. The coefficient of restitution (COR), effective mass at the impact point, and the location of impact relative to the club’s center of percussion determine how much of the clubhead’s kinetic energy becomes ball kinetic energy (commonly summarized as the smash factor). From an energy perspective,small increases in impact efficiency can rival ample increases in raw clubhead speed,which underscores why coaching and equipment tuning aim to optimize both velocity and impact quality.

From the athlete side,neuromuscular and ground-interaction variables modulate both peak speed and transfer efficiency. Ground reaction forces,the timing of hip-to-shoulder rotation,and the rapid activation of wrist flexors/extensors shape the velocity profile of the clubhead during downswing.Measurement technologies-radar-based launch monitors,high-speed videography,and marker-based motion capture-provide complementary data streams for decomposing velocity,angular acceleration,and impact kinematics; each metric informs distinct intervention pathways in training or equipment selection. Emphasizing coordinated sequencing frequently enough yields greater improvements in ball speed than isolated strength interventions.

- Shaft stiffness and kick point – influences timing of energy transfer and trajectory.

- Clubhead mass and MOI – higher MOI increases forgiveness but can lower peak speed.

- Loft and CG position – modify launch angle and spin rate for given impact speed.

- Grip size and grip torque – affect wrist mechanics and release timing.

- Ball construction – core and cover properties change COR and spin outcomes.

Equipment decisions necessarily involve trade-offs between raw speed, forgiveness, and workability. Increasing clubhead mass or MOI tends to stabilize off-center impacts at the cost of accelerating the club to the same peak speed; conversely,an ultra-light,low-MOI head may be easier to accelerate but will penalize mis-hits. Shaft selection (stiffness,torque,length) must align with a player’s release profile and temporal sequencing to preserve impact efficiency.Thus, objective fitting-using launch data and biomechanical measures-should guide choices rather than subjective feel alone.

| Equipment Variable | Primary performance effect |

|---|---|

| Shaft Flex / Length | Alters timing; affects launch and dispersion |

| Clubhead MOI | Stability vs. peak speed trade-off |

| Ball Construction | Modulates spin and energy return (COR) |

Optimizing distance and precision requires a combined approach: improve biomechanical sequencing to raise available clubhead velocity while selecting equipment that preserves or enhances impact efficiency under the player’s typical strike pattern. Practical optimization is iterative-collecting launch monitor data, refining swing mechanics, and adjusting equipment until marginal gains in speed and transfer efficiency converge. In applied settings, a coordinated program of technical coaching, physical preparation, and evidence-based fitting yields the most consistent increases in on-course performance.

Clinical Assessment and Measurement Technologies: Motion Capture, Force Platforms, and Wearable Sensors

Modern assessment of the golf swing in clinical and performance settings leverages three complementary measurement modalities that together span kinematic, kinetic and neuromuscular domains. **Optical motion capture** systems quantify segmental rotations, joint centers and ballistics of the club at high spatial and temporal resolution, providing the kinematic foundation for analysis. **Force platforms** measure vertical, mediolateral and anteroposterior ground reaction forces (GRFs), center-of-pressure (CoP) trajectories and temporal loading patterns that drive kinetic models. **Wearable sensors**-inertial measurement units (IMUs), wireless electromyography (EMG) and pressure insoles-extend assessment outside the laboratory, capturing field-based dynamics and muscle activation patterns during on-course practice or competition.

Clinical protocols must be designed to ensure reproducibility and clinical relevance.Recommended procedural elements include:

- Standardized marker/IMU placement aligned to anatomical landmarks to reduce inter-session variability.

- Sampling rates of ≥200 Hz for optical capture and ≥1000 Hz for force measurement when calculating impact transients and rate-of-force development.

- EMG normalization to maximal voluntary contractions or dynamic tasks to allow between-subject comparisons.

Careful instruction of trial cadence and use of a warm-up protocol minimize fatigue-related confounds and improve interpretability of longitudinal assessments.

Data integration relies on rigorous synchronization and processing pipelines. Time-synchronizing motion capture, force platforms and wearables enables inverse dynamics to estimate joint moments and power. Signal processing best practices-zero-lag filtering with appropriate cut-off frequencies, gap-filling for occluded markers, and cross-correlation checks-reduce artefact propagation. Clinicians should be aware of model assumptions (rigid segments, joint center estimation) and perform sensitivity analyses to identify which variables (e.g., pelvis rotation, lead knee moment) are robust versus model-dependent.

Translational applications target both technique refinement and injury prevention. Objective metrics commonly used in clinical decision-making include: peak GRF and its timing, CoP excursion and transfer, thorax-pelvis separation (X-factor) and segmental angular velocities, plus muscle onset latency and amplitude from EMG. The table below summarizes common mappings between technology and clinical metrics for rapid reference.

| Technology | Typical Metrics | Clinical Use |

|---|---|---|

| Optical motion capture | segment angles,angular velocity,X‑factor | Swing sequencing,mobility deficits |

| Force platforms | Peak GRF,CoP path,rate of force | Weight shift,load symmetry,injury risk |

| Wearables (IMU/EMG) | Clubhead acceleration,muscle timing | Field monitoring,fatigue and motor control |

When selecting technology for clinical practice,balance **validity**,**reliability** and practicality. High-fidelity lab systems provide gold-standard measures for diagnostic assessment, whereas wearables enable ecological validity and longitudinal monitoring. Clinicians should establish minimal detectable change thresholds, use normative or sport-specific reference data, and prioritize measures that directly inform intervention (e.g., asymmetrical cop indicating need for balance retraining). Emerging directions-real-time IMU-driven feedback, machine-learning models for pattern recognition and cloud-based dashboards-promise to close the loop between assessment and on-going, individualized intervention.

Evidence based Training Interventions and Technical Modifications for Performance and Rehabilitation

Contemporary practice integrates biomechanical evidence with clinical reasoning to prescribe targeted interventions that enhance performance while minimizing injury risk. Interventions should be grounded in the hierarchy of evidence-systematic reviews, randomized controlled trials, and high-quality cohort and biomechanical studies-and translated to the golfer through principled application of motor control, tissue capacity and load-response frameworks. Emphasis is placed on measurable outcomes (e.g., club head speed, kinematic sequence fidelity, symptomatic relief) and on aligning training stimuli with the specific mechanical demands observed during swing phase analyses. Individualization and iterative reassessment are essential: what improves power in one athlete may exacerbate joint loading in another if underlying mobility or motor control deficits are unaddressed.

Strength and conditioning strategies validated by biomechanical research prioritize multiplanar force production and controlled deceleration. Evidence-based modalities include:

- Rotational power training (medicine ball throws, resisted cable chops)-to increase angular impulse and club head speed;

- Eccentric hip and trunk strengthening-to improve deceleration capacity and reduce passive tissue strain;

- Thoracic mobility and scapular control drills-to restore proximal sequencing and reduce compensatory lumbar motion;

- Plyometric and rate-of-force-development work-to convert strength into on‑club velocity;

- Progressive overload with periodized load management-to raise tissue capacity without provoking symptom recurrence.

These interventions are most effective when integrated with sport-specific tasks and preserved swing mechanics during loaded practice.

Technical modifications derived from biomechanical assessment can both enhance efficiency and protect vulnerable tissues.Examples supported by kinematic and kinetic analyses include modest reduction of maximal shoulder external rotation to lower rotator cuff strain, optimized weight-shift sequencing to reduce lumbar shear, and controlled wrist release timing to balance carry vs. joint load. Use of temporal constraints (e.g., abbreviated backswing) and equipment adjustments (shaft flex, grip changes) have demonstrated utility in single-subject and cohort studies for preserving distance while diminishing peak joint moments. Implementation must maintain the kinematic sequence-proximal-to-distal activation-so that force is transmitted effectively and compensatory overload is avoided.

| Intervention | Primary outcome | Evidence level |

|---|---|---|

| Rotational medicine ball training | ↑ Club head speed | Moderate |

| Eccentric hip program | ↓ Lumbar loading | Moderate |

| Thoracic mobility drills | ↑ Trunk rotation ROM | Emerging |

| Tempo/back‑swing modification | ↓ Shoulder torque | Low-Moderate |

Rehabilitation and return-to-play should be criterion-driven rather than time-driven: objective thresholds (pain-free ROM, symmetry of rotational force, normalized force‑time curves on force plates, restoration of technique under fatigue) guide progression. Regular re-testing with the same instruments used in initial analysis ensures interventions produce meaningful biomechanical change.

Practical application requires ongoing monitoring and a multidisciplinary team: coaches, physiotherapists, strength and conditioning specialists and biomechanists collaborate to reconcile performance goals with tissue health. Wearable inertial sensors, 2D/3D motion capture and force platforms provide complementary data streams for real‑time feedback and longitudinal tracking; augmented feedback (visual/kinematic) accelerates motor learning when faded appropriately. future research should focus on large-scale randomized trials that compare combined S&C plus technical modification strategies, and on establishing minimal clinically critically important differences for biomechanical metrics relevant to golfers across skill levels and age groups.

Q&A

Below is an academic, professionally toned question-and-answer (Q&A) suite intended to accompany an article titled “Biomechanical Analysis of the Golf Swing: Theory.” The Q&A addresses essential theory,measurement,analytic methods,neuromuscular control,kinetic/kinematic relationships,implications for technique refinement,and injury risk mitigation.Citations to general definitions of biomechanics are indicated where appropriate.

1. What is meant by “biomechanical analysis” in the context of the golf swing?

– Biomechanical analysis applies mechanical principles to living systems to quantify how forces, motions, and muscle actions produce movement (see biomechanics definitions: CEHD, Physiopedia, Wikipedia). In golf, it consists of measuring and interpreting kinematic (motion), kinetic (forces and moments), and neuromuscular (muscle activation and timing) variables that underlie swing performance and tissue loading.

2. What are the primary phases of the golf swing from a biomechanical perspective?

– The swing is commonly segmented into address, backswing (early and late), transition, downswing (acceleration), impact, and follow‑through (deceleration).Each phase has characteristic joint positions, velocity patterns, force application, and neuromuscular strategies relevant to performance and injury risk.

3. Which kinematic variables are most informative for understanding swing performance?

– Key kinematic variables include segmental angular displacements and velocities (pelvis, thorax, shoulders, arms, wrists), intersegmental separation metrics such as the “X‑factor” (trunk-pelvis rotation differential), sequencing and timing of peak angular velocities (proximal‑to‑distal sequence), clubhead path and orientation, and joint angles at impact. metrics of rotational velocity and coordinated timing strongly relate to clubhead speed and ball launch conditions.

4. How do kinetic measures complement kinematic data?

– Kinetics quantify the forces and moments that drive observed motions: ground reaction forces (GRFs), joint moments and powers from inverse dynamics, and external loads applied to the club. GRF patterns and their timing illuminate how the body generates and transfers force through the kinetic chain; joint power analyses identify which segments contribute energy to the club (power generation vs absorption).

5. What is the proximal‑to‑distal sequence and why is it critically important?

– The proximal‑to‑distal sequence is the ordered activation and acceleration of segments from the center of mass outward (pelvis → thorax → upper limb → club). This timing maximizes angular momentum transfer and peak clubhead speed while minimizing excessive distal loading.Disruption of this sequence reduces efficiency and can increase injury risk by placing abnormal loads on distal joints.

6. What neuromuscular dynamics are critical to an effective golf swing?

– Critical dynamics include precise timing of muscle activation, the use of stretch‑shortening cycles in key musculature (e.g., trunk rotators, hip extensors, shoulder stabilizers), intermuscular coordination for stabilizing proximal segments while accelerating distal segments, and anticipatory postural adjustments that prepare for planned accelerations. EMG studies typically show phasic activation peaks timed to segmental accelerations.

7. Which muscles are most important for power generation and stabilization?

– Power contributors include hip extensors/rotators (gluteus maximus/medius), trunk rotators (obliques, multifidus), and scapulothoracic muscles that position the upper limb. Stabilizers include core musculature (transversus abdominis, multifidus), rotator cuff muscles, and lower‑limb muscles that control GRFs and pelvis stability.

8. How are ground reaction forces used to assess swing mechanics?

– GRFs (vertical,mediolateral,anteroposterior) quantify how the body interacts with the ground to generate rotational and translational forces. Peak GRF magnitudes,timing of weight shift,and medial/lateral force patterns indicate how effectively lower‑limb force is transferred through the kinetic chain; they also help identify asymmetries and compensatory strategies.

9. What measurement modalities are standard in biomechanical analyses of the golf swing?

– Common tools include optical motion capture (marker‑based or markerless) for kinematics, force platforms for GRFs, wearable inertial sensors (IMUs), electromyography (EMG) for muscle activation, high‑speed video for clubhead diagnostics, and musculoskeletal modeling (inverse dynamics, forward dynamics) for joint kinetics and muscle force estimation.

10. What are the typical analytic approaches used (e.g., inverse dynamics, modeling)?

– Inverse dynamics uses measured kinematics and external forces to compute net joint moments and powers. Musculoskeletal models add muscle‑level resolution via optimization or EMG‑driven approaches. Forward dynamics and simulation can be used to explore how changes in motor control or anatomy affect outcomes. Statistical and machine‑learning methods identify predictors of performance and injury risk.11. How does segmental mobility (e.g., hips and thorax) affect swing mechanics and performance?

– Adequate rotational mobility in hips and thorax enables larger X‑factor and efficient energy transfer. Limited mobility often causes compensatory increases in spinal extension or wrist/shoulder loading,which can reduce clubhead speed and raise injury risk. Mobility must be balanced with stability to allow controlled energy transfer.12. What is the relationship between swing technique and injury risk?

– Inefficient technique (e.g., poor sequencing, excessive lateral bending, abrupt deceleration) increases joint and tissue loads, particularly in the lumbar spine, lead elbow, wrist, and shoulder.Repetitive high‑load exposures without recovery or with inadequate muscular support predispose to overuse injuries. Technique that emphasizes smooth proximal‑to‑distal transfer, appropriate deceleration strategies, and reduced harmful spinal shear moments mitigates risk.

13. Which injuries are most commonly associated with the golf swing and what biomechanical mechanisms underlie them?

– Common injuries include low back pain (excessive spinal rotation plus lateral bending and shear), medial/ lateral epicondylalgia of the elbow (repetitive valgus/varus and eccentric loading), wrist tendinopathies (excessive ulnar deviation/extension at impact), and shoulder impingement (repetitive overhead rotational stress). Mechanisms involve cumulative high moments, eccentric loading, and poor load distribution across the kinetic chain.

14. How can practitioners use biomechanical findings to refine a golfer’s technique?

– Practitioners can identify deficits (mobility, strength, sequencing, timing) via testing and measurement, then apply targeted interventions: technical adjustments to improve sequencing and reduce harmful postures, mobility/stability exercises for hips and trunk, strength/power training to enhance force production, and motor learning drills that emphasize timing. Objective measures (e.g., clubhead speed, pelvis-thorax timing, GRF profiles) guide progress and individualize training.

15. What training interventions are evidence‑based for improving swing performance and reducing injury risk?

– Interventions with empirical support include: rotational power training (medicine ball throws, cable chops), hip and thoracic mobility work, core stability and eccentric control exercises, progressive overload for lower‑limb and trunk strength, and neuromuscular training emphasizing timing and coordination. Gradual progression, task specificity, and monitoring of pain/loading are essential.

16. How should clinicians and coaches balance performance goals with injury prevention?

– Adopt a systems approach: prioritize safe mechanics that allow maximal sustainable performance, integrate physical conditioning that addresses identified deficits, implement load management (frequency/intensity monitoring), and use objective metrics to inform technical modifications. Risk-benefit decisions should be individualized by age, tissue capacity, and competitive demands.

17. What limitations should readers be aware of when interpreting biomechanical studies of the golf swing?

– Laboratory conditions (e.g., certain clubs, artificial surfaces, marker sets) may not fully reproduce on‑course variability.Small sample sizes, cross‑sectional designs, and heterogeneous skill levels limit generalizability. Inverse dynamics yields net joint moments but not direct muscle forces; musculoskeletal models rely on assumptions about muscle geometry and recruitment. Wearable sensors trade some accuracy for ecological validity.

18.How do wearable sensors and field technologies change biomechanical assessment?

– Wearables (IMUs, instrumented clubs, pressure insoles) enable in‑field monitoring of kinematics, GRF proxies, and club metrics across practice and play, improving ecological validity and longitudinal load tracking. They facilitate continuous feedback and individualized interventions, though data requires careful calibration and interpretation.

19. What are promising directions for future research in golf‑swing biomechanics?

– Future work includes subject‑specific musculoskeletal modeling,integration of EMG‑driven simulations,longitudinal studies linking biomechanical exposures to injury incidence,machine‑learning methods for personalized technique optimization,and translation of lab findings to effective field‑based interventions and rehabilitation protocols.

20. How can researchers and practitioners ensure biomechanical insights are translated into practical coaching cues?

– translate quantitative findings into simple, observable movement cues tied to underlying mechanics (e.g., “initiate downswing with pelvis rotation” to emphasize proximal activation). Use objective metrics to validate cue efficacy, incorporate drills that replicate desired kinematic and kinetic patterns, and align conditioning programs with technical goals. Iterative feedback between measurement and coaching ensures effective translation.

21. Are there evidence‑based thresholds or normative values for safe or optimal loads in golf?

– There are no universally accepted single thresholds because safe loading depends on individual tissue capacity,history,and cumulative exposure. Instead, trends (e.g.,excessive peak trunk rotation velocity without adequate pelvic rotation,abrupt increase in practice volume) signal elevated risk. Use individualized baselines and monitor relative changes in load and pain.

22. What practical assessment battery do you recommend for a extensive biomechanical screening of a golfer?

– A practical battery could include: motion analysis of swing (video or sensor-based) for sequencing and kinematic metrics; force plate or pressure‑insole assessment for weight‑shift and GRF patterns; dynamic posture and mobility screening for hips, thorax, and shoulders; strength and power tests (hip extension, rotational power); and movement control/core endurance tests. Combine with subjective history and load monitoring.

23. How should clinicians manage a golfer presenting with low back pain linked to swing mechanics?

– Perform a thorough differential diagnosis. Biomechanical management may include: correcting harmful swing patterns (reduce combined rotation/extension/lateral bending), improving hip and thoracic mobility, strengthening and motor control of the lumbopelvic region, progressive return to swing intensity with load monitoring, and addressing equipment factors (shaft flex, lie angle). Coordinate with medical management as indicated.

24. How can biomechanical analyses accommodate diffrent skill levels, ages, and swing styles?

– Analyses should be contextualized: elite players prioritize maximal power and may accept higher transient loads, while recreational or older golfers need stability and load management. Use relative metrics (sequencing accuracy, symmetry, change scores) rather than absolute values alone. Tailor interventions to individual capacity, goals, and constraints.

25.What is the single most important biomechanical principle for coaches and clinicians to remember?

– Efficient transfer of energy from the ground through the pelvis and trunk to the upper limb (proximal‑to‑distal sequencing) under controlled, repeatable motor patterns maximizes performance while minimizing undue distal joint loading. Interventions should therefore target sequencing, segmental mobility/stability balance, and tissue capacity.

If you would like, I can:

– Convert these Q&As into a printable FAQ for practitioners,

– Expand any answer with representative data, representative study citations, or example assessment protocols,

– Provide a short drill set and conditioning program mapped to specific biomechanical deficits.

Concluding Remarks

the theoretical framework presented here synthesizes kinematic, kinetic, and neuromuscular perspectives to clarify how coordinated segmental motion, force generation, and sensorimotor control together produce effective and repeatable golf swings. Framing the golf swing within core biomechanical principles-where structure and function are linked and internal and external forces are determinative-permits systematic interpretation of performance variability, power transfer, and common injury mechanisms. By situating empirical observations within mechanistic models, coaches and clinicians can translate abstract insights into concrete diagnostic cues and targeted interventions that prioritize both performance enhancement and tissue protection.

Looking forward, advancing this theoretical foundation will depend on integrative research that combines laboratory-grade motion analysis, computational modeling, and ecologically valid field measurements (including wearable sensors). Longitudinal and intervention studies are needed to validate model-derived prescriptions, to quantify inter-individual responsiveness, and to delineate trade-offs between performance gains and injury risk across diverse populations.Interdisciplinary collaboration-linking biomechanics, motor control, sports medicine, and coaching science-will be essential to move from descriptive inference to evidence-based technique refinement and personalized training programs.

Ultimately, a rigorous, theory-driven biomechanical approach offers a pathway to refine golf technique with greater precision and safety. By continuing to align mechanistic understanding with applied practice, researchers and practitioners can jointly foster performance improvements that are both measurable and sustainable.

Biomechanical Analysis of the Golf Swing: Theory

What is Biomechanics and Why It Matters for the Golf Swing

Biomechanics is the scientific study of forces and motion in living systems – in our case, how the human body produces, transmits, and controls motion during the golf swing.Understanding biomechanics gives coaches, players, and sports scientists a language and measurable metrics for identifying efficient swing mechanics, improving power and consistency, and reducing injury risk (see general definitions at Wikipedia and Physio-Pedia).

Key Biomechanical Concepts in Golf Swing analysis

- Kinematics – describes motion (angles, angular velocities, trajectories) of body segments without reference to forces.

- Kinetics – analyzes forces and moments (torque), including ground reaction forces (GRF) and joint moments that produce clubhead speed.

- Kinetic chain – the sequential activation from feet → hips → torso → arms → club; efficient sequencing (proximal-to-distal) maximizes energy transfer to the ball.

- centre of Mass and Stability – balance, weight shift, and postural control influence repeatability and power.

- Timing and Tempo – the temporal coordination of segment rotations is frequently enough more critical than maximal strength alone.

Phases of the Golf Swing: Biomechanical Markers

Breaking the swing into phases helps quantify kinematics and kinetics for diagnosis and training.

| Phase | primary Biomechanical Goals | Typical Measured Metrics |

|---|---|---|

| Address / Setup | Posture,grip,alignment,pre-load | Spine angle,hip hinge,weight distribution |

| Backswing | Rotation,coil,lag creation | Torso rotation,shoulder turn,wrist angle |

| Transition | Weight shift,sequencing initiation | Lead leg loading,pelvis rotation onset,GRF changes |

| Downswing | Proximal→distal energy transfer,clubhead acceleration | Angular velocity peaks,hip/shoulder separation,clubhead speed |

| Impact | Clubface control,launch conditions | Clubhead speed,face angle,attack angle |

| Follow-through | dissipation of energy,balance | Torso rotation,deceleration patterns |

Motion Capture,Wearables and Objective Measurement

Modern golf swing analysis uses high-speed optical motion capture,inertial measurement units (IMUs),force plates,and launch monitors. Together these tools provide a multi-dimensional picture:

- Motion capture (optical) quantifies 3D joint angles and segment velocities (useful to calculate angular acceleration and sequence).

- IMUs enable on-course or range-based kinematic tracking when lab equipment is impractical.

- Force plates measure ground reaction forces and center-of-pressure shift, revealing how lower-body mechanics support swing power.

- Launch monitors measure clubhead speed, ball speed, launch angle, spin – linking biomechanics to on-ball outcomes.

Biomechanical Principles That Optimize Ball Striking

1. Efficient Proximal-to-Distal Sequencing

The kinetic chain should activate from the ground up: foot pressure and pelvis rotation generate angular momentum that transfers through the torso to the arms and club. Proper sequencing creates a cascade of angular velocities – hips peak, then torso, then arms, then clubhead – maximizing clubhead speed wiht minimized muscular overload.

2. Hip-Torso Separation (X-Factor)

Creating a controlled rotational difference between the hips and shoulders on the backswing stores elastic energy in the obliques and lumbar region. Research suggests moderate to high X-factor values are associated with greater rotational power, but excessive separation increases spine stress and inconsistency.

3. Ground reaction Force (GRF) Utilization

Effective drivers of power use GRF to push off the trail leg and then transfer weight to the lead side. Monitoring vertical and horizontal GRF patterns highlights whether a player is using the ground efficiently or relying only on upper-body effort.

4. Wrist and Shaft Kinematics (Lag)

Creating wrist lag (a delayed release) through proper sequencing allows the club to accelerate rapidly in the last fraction of a second before impact. Measuring shaft angle and wrist extension helps quantify lag and release timing.

5.Stability and Dynamic Balance

Maintaining a stable base while allowing rotational freedom reduces energy leaks and maintains clubface control. Center-of-mass displacement should be controlled – not overly swaying – to achieve consistent impact geometry.

Common Biomechanical Faults and what They Cause

- Early extension (hips moving toward the ball): loss of spine angle causes inconsistent low-to-high attack and reduces power.

- Over-rotation in the upper body without lower-body engagement: creates timing faults and slice tendencies.

- Insufficient weight shift: leads to reduced clubhead speed and weak contact.

- Rapid or mistimed release: produces hooks or heeled/toed strikes due to clubface misalignment at impact.

How to Quantify Swing improvements

key performance indicators to track during biomechanical training:

- Clubhead speed and ball speed (mph)

- Launch angle and spin rate (degrees, rpm)

- sequence timing: time-to-peak angular velocity for hips, torso, arms (ms)

- GRF peaks and impulse (N, Ns)

- Impact parameters: face angle, attack angle, center of pressure on face

Rapid note: Lab-based biomechanics gives the most precise values, but even simple video analysis with frame-by-frame review can reveal timing and positional errors valuable to golfers and coaches.

Practical Training Tips Based on Biomechanics

Warm-up and Mobility

- Dynamic hip and thoracic rotation drills to improve range of motion for backswing and follow-through.

- Glute activation and single-leg stability drills to enhance GRF utilization and balance.

Sequencing and Tempo Drills

- Slow-motion swings focusing on hip rotation initiation, then gradually increase speed to feel proximal-to-distal timing.

- Use a metronome or 3:1 tempo cues (backswing:downswing ratio) to reinforce consistent tempo.

Power and Transfer Drills

- Medicine ball rotational throws to train explosive torso transfer.

- Step-and-swing drills with a short stride to emphasize weight transfer and hip drive.

Impact and Face Control

- Impact bag work to teach correct lead-side compression and clubface control.

- Short-to-mid iron punch shots to ingrain impact geometry and shallow attack angles.

Short Case study Examples

Below are two illustrative examples (anonymized) showing biomechanical changes and outcomes.

| Player | biomechanical Issue | intervention | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Player A (club golfer) | Overactive upper body; poor hip rotation | Hip mobility & medicine-ball drills; tempo training | Clubhead speed +5 mph; fairway hit % improved |

| Player B (young amateur) | Early extension & weight collapse | Single-leg stability; impact bag; posture drills | More consistent strike, higher ball speed retention |

First-hand Coaching Insights

From working with golfers of varied levels, the fastest gains often come from:

- Addressing mobility limitations first – you can’t sequence well if you can’t rotate.

- Using simple objective metrics (clubhead speed, number of centered strikes) to measure progress.

- Prioritizing repeatable movements over maximal effort early in coaching: consistency builds the platform for power later.

SEO Keywords Naturally Embedded

This article incorporates core search terms golfers and coaches use: golf swing biomechanics, golf swing analysis, swing mechanics, clubface control, ground reaction forces, motion capture golf, kinetic chain golf, swing tempo, hip rotation golf, and golf swing kinematics. Use these terms in your web headings and alt text when publishing to boost on-page relevance for search engines.

How to Apply Biomechanical Theory to Your Practice

A structured approach to applying biomechanical theory:

- Baseline assessment: record video (front and down-the-line), measure clubhead speed, and if possible, collect force/IMU data.

- Identify one or two key mechanical faults – avoid changing everything at once.

- Design 2-4 week microcycles focusing on mobility, sequencing, and impact geometry drills.

- Re-assess objectively (video, speed, launch data) and iterate.

further reading & Resources

For foundational definitions and deeper context, consult reputable biomechanics overviews such as Biomechanics – Wikipedia and practical summaries like Physio-Pedia. For applied golf research,seek peer-reviewed journals on sports biomechanics and technology providers that publish validation studies for motion-capture and launch-monitor systems.

Actionable 30-Day Biomechanics Action Plan (Summary)

- Week 1: Mobility and posture – thoracic rotation, hip flexor release, glute activation.

- week 2: Sequencing and tempo – slow-motion swings, metronome tempo work.

- Week 3: Power transfer – medicine-ball throws, step-and-drive drills, force-plate awareness if available.

- Week 4: Impact and consistency – impact bag, centered strike drills, integrate full swings at target speeds.

WordPress Publishing Tips for SEO

- Use the meta title and meta description provided at the top of this article when populating Yoast or Rank Math fields.

- Include at least one descriptive image with alt text containing keywords like “golf swing biomechanics” or “golf swing analysis”.

- Structure content with H1/H2/H3 as shown and use internal links to related coaching pages or drill videos.

- Use schema markup (Article or HowTo) if you include step-by-step drills to improve rich result potential.

Want a customized biomechanical checklist for your swing (video or live session suggestion)? I can provide a printable checklist and drill progression tailored to your current swing data – share a short clip and a few numbers (clubhead speed, handicap/goals) and I’ll draft an actionable plan.