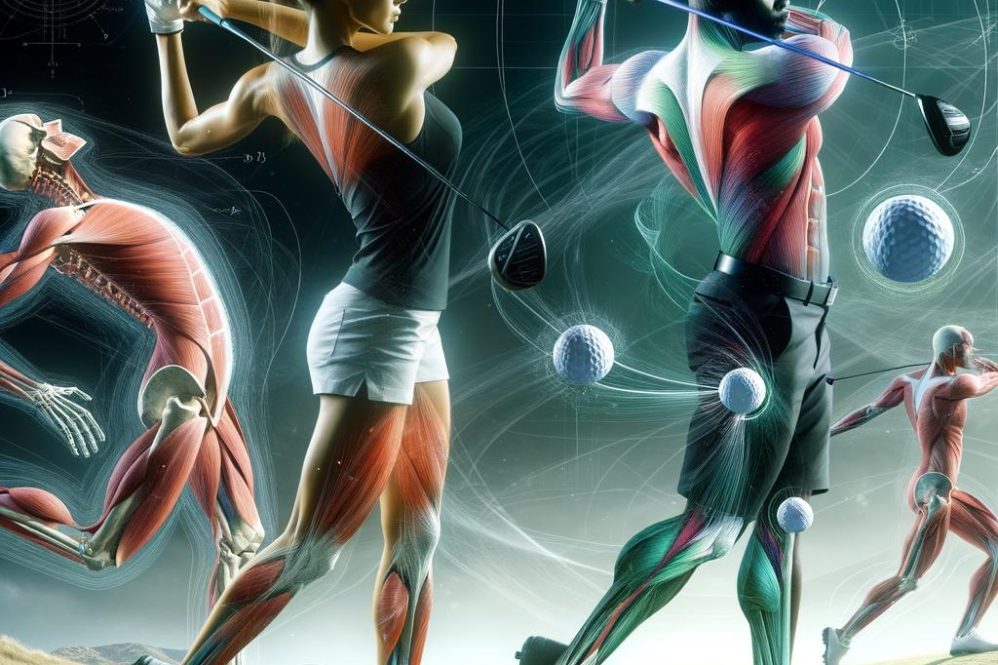

Teh ability of a golfer to generate performance and resist injury is the product of how movement mechanics interact with the bodily systems that create, transmit, and sustain force. Drawing on biomechanics-the field that connects anatomical structure to movement function-and principles from exercise physiology, a focused review of golf‑specific conditioning shows how joint motion, kinetic chains, muscular strength and power, neuromuscular control, and metabolic capacity together determine swing economy and consistency. This synthesis integrates theoretical models and applied findings to map the principal mechanical drivers of an effective swing (for exmaple, swing plane, timing of segmental sequencing, ground reaction forces, and joint loading) to the physiological qualities that enable them (including maximal and rapid force production, mobility, proprioception, and energy‑system readiness). It also examines how laboratory measurements can be converted into practical field metrics and summarizes training tenets-specificity, progressive overload, and motor learning-that produce skills transferable to on‑course performance. Beyond maximizing output, this integrated approach helps reduce injury risk by coupling movement analysis with targeted conditioning to enhance force transfer through the kinetic chain and prevent harmful loading patterns. The sections that follow draw on interdisciplinary sources across biomechanics, sports medicine, and applied conditioning to offer actionable guidance for coaches, clinicians and researchers working to align training with the mechanical and physiological requirements of the contemporary golf swing.

kinematic Sequencing and Segmental Coordination in the Golf Swing: Practical Assessment and Focused Training

Maximizing clubhead velocity while maintaining accuracy depends on a repeatable proximal‑to‑distal sequence: the pelvis initiates rotation, the torso follows, then the arms and finally the clubhead accelerate. Modern motion‑capture work highlights that the temporal spacing of peak angular velocities-when each segment reaches its maximum speed-matters as much as the magnitudes of those peaks. Core biomechanical indicators of efficient sequencing include pelvis‑to‑torso separation (commonly called the X‑factor), the timing of segmental peak angular velocities, and the timing and pattern of ground reaction forces. Together these measures describe how effectively an athlete synthesizes segmental motions into a coordinated kinetic chain.

Robust assessment blends high‑precision lab measures with portable devices suitable for the practice range. Common measurement tools are:

- 3D optical motion capture for detailed inter‑segment angles and temporal sequencing;

- Inertial measurement units (IMUs) for on‑course angular velocity profiles and immediate feedback;

- Force platforms to capture ground reaction timing,weight‑shift patterns and rate of force development;

- High‑speed video and club sensors to relate clubhead kinematics to body sequencing.

Turning diagnosis into training means prescribing phase‑specific interventions tied to the athlete’s primary limitation-timing, force magnitude, or mobility. Productive modalities include rotational medicine‑ball throws emphasizing speed to build proximal power, resisted cable chops to strengthen torso/pelvis dissociation under load, thoracic mobility progressions to increase safe X‑factor, and metronome‑paced timing drills or reversed‑sequence activations to refine time‑to‑peak relationships. Programs should then progressively restore proper sequencing across increases in swing speed and task complexity so gains carry into competition.

To aid interaction between coaches, therapists and players, map each measurable deficit to a concise training target and a practical intervention. Representative kinematic metrics, common interpretations, and short‑term training aims suitable for a 6-12 week block include:

| metric | Interpretation | Training Target |

|---|---|---|

| Peak pelvis → torso time lag | Late torso response diminishes momentum transfer | Timed med‑ball slams + metronome sequence drills |

| X‑factor magnitude | Restricted elastic recoil and rotational output | thoracic mobility + loaded rotation sets |

| Time‑to‑peak clubhead velocity | Distal segments poorly synchronized | Progressive speed swings + lower‑body plyos |

Ground Reaction Forces, Lower‑Limb Mechanics and Energy Transfer: Profiling Strength and progressions for Higher Clubhead Speed

High clubhead velocities begin with efficient lower‑limb mechanics that convert ground impulses into rotational and translational energy traveling up the chain. Modern analyses look beyond peak vertical or horizontal GRFs to include timing of force submission and inter‑limb asymmetry. Clinicians thus assess both discrete quantities (peak GRF, impulse) and temporal features (time‑to‑peak force, rate of force development) to form useful athlete profiles.

| Assessment | Metric | Practical target / note |

|---|---|---|

| Vertical countermovement jump | Peak power & RFD | High RFD linked to faster energy transfer |

| Single‑leg hop | Distance & symmetry | <10-15% inter‑limb asymmetry preferred |

| Drop jump | reactive strength index (RSI) | Reflects stretch‑shortening efficiency |

Plyometric and ballistic training should be organized as a progression from bilateral,vertical emphasis to unilateral,multi‑planar tasks that mirror swing demands. Examples of a sensible progression:

- Foundational: squat jumps, double‑leg hops with brief ground contact;

- Transitional: drop jumps, lateral bounds and broad jumps introducing greater eccentric load;

- Advanced: single‑leg bounds, reactive rotational med‑ball rebounds and sport‑specific decelerations.

Strength profiling steers exercise selection and loading: prioritize hip‑extensor and external‑rotator strength, eccentric knee control, and appropriate ankle stiffness to optimize upward force transfer. Training aims should include increasing maximal force (through heavier, slower strength work) and improving RFD (via low‑volume, high‑intensity plyometrics and ballistic lifts). When integrating these into periodized plans, apply progressive overload and specificity while watching for maladaptive asymmetries. practical guidelines:

- Frequency: 1-3 focused plyometric/contrast sessions per week depending on phase;

- Volume: keep total contacts low at high intensity; prioritize quality and short ground contact times;

- Safety: cue soft, controlled landings, trunk stability and pain‑free loading-delay maximal plyometrics until eccentric strength is adequate.

Spinal Mobility, Trunk Stability and Rotational Power: Screening and a progressive Conditioning Roadmap

A compact battery of objective screens links spinal mobility to trunk stability and rotational output, giving a practical starting point for conditioning. Combine regional ROM checks (thoracic rotation,lumbar flexion/extension,hip internal/external rotation) with dynamic control tests (single‑leg stance with perturbation,anti‑rotation Pallof press,and back‑extensor endurance tests such as Sorensen). Minimal field tools include an inclinometer or smartphone goniometer, a medicine ball (2-6 kg), and a timer. Useful screens are:

- Seated thoracic rotation: assess symmetry and degrees of rotation;

- Active lumbar flexion/extension: confirm pain‑free range and control at end range;

- Pallof (anti‑rotation) press: evaluate transverse‑plane stability.

Interpret screening results within clinical context. Asymmetries greater than roughly 10-15% or notably limited thoracic rotation (commonly less than 30-40° in competitive players) should be prioritized. Screening must also identify red flags-new radicular pain, progressive weakness, gait disturbance or signs of neurogenic claudication require immediate medical evaluation and imaging rather than aggressive rotational loading. For non‑urgent findings, classify deficits as mobility restrictions, motor‑control limitations or endurance shortfalls to steer interventions.

A logical, evidence‑based conditioning sequence moves from tissue planning and mobility to integrated stability, then to force development and speed‑specific power. A pragmatic four‑phase model-Mobility → Activation/Stability → Strength/Capacity → Power/Transfer-matches objectives to drills and typical microcycle emphasis:

| Phase | Primary Goal | Representative Drills | Typical Focus (2-6 weeks) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mobility | Restore thoracic and hip ROM | Foam‑thoracic mobilizations, thoracic windmills, hip internal rotation mobilizations | Daily, low load |

| Activation/Stability | Improve segmental control | Dead‑bug progressions, Pallof press, single‑leg RDL with tempo | 3×/week, motor control |

| Strength/Capacity | Increase load tolerance | Loaded carries, Romanian deadlifts, controlled cable chops | 2-4 sets, 6-12 reps |

| power/Transfer | Develop elastic rotational power | Med‑ball rotational throws, band‑resisted swings, explosive chops | High velocity, low volume |

Dose programme variables to the phase and individual risk. Early phases emphasize higher frequency, lower intensity, and technical mastery; later phases reduce frequency while increasing intensity and velocity to encourage transfer to the swing. Monitor outcomes such as rotation symmetry, plank endurance, and med‑ball throw distance or velocity; adjust loads in 5-10% increments. For players with spine pathology, prioritize pain‑free ranges, avoid repetitive end‑range lumbar rotation under load, and integrate spine specialist input. The overarching objective is progressive specificity: restore mobility, stabilize the trunk under perturbation, then convert capacity into controlled rotational power that matches the temporal and amplitude demands of the swing.

Shoulder Complex and Scapular Mechanics in Club Delivery: Assessment, Prevention and Rehab Pathways

The shoulder complex serves as the mobile interface between the torso and the clubhead. Performance hinges on coordinated glenohumeral motion,healthy scapulothoracic rythm and integration with whole‑body sequencing. During delivery the scapula needs to behave as a stable, eccentrically controlled platform-upwardly rotating, posteriorly tilted and externally rotated-so that the rotator cuff and deltoid can centralize the humeral head. When scapular mechanics are impaired or thoracic extension is limited, load shifts to passive tissues and the player becomes more susceptible to impingement, tendinopathy, labral strain and AC‑joint irritation. Distinguishing technique‑driven loading from tissue vulnerability is critical for targeted assessment and treatment.

Field and bedside appraisal should quantify static capacity and dynamic control. Useful tests include:

- Scapular dyskinesis observation during repeated overhead flexion/abduction to look for asymmetry or winging;

- Glenohumeral ROM (internal/external rotation, horizontal adduction) compared bilaterally;

- Rotator cuff and periscapular strength (isometric ER/IR, serratus anterior protraction, lower trapezius endurance);

- Dynamic kinetic‑chain tasks such as single‑leg balance with a medicine‑ball throw to assess the shoulder within whole‑body demands.

| Assessment | Target | Clinical Clue |

|---|---|---|

| Scapular control | Fluid upward rotation, no winging | Altered kinematics → early rehab focus |

| ER strength | ≥90% contralateral | Deficit → reduce deceleration load |

| Thoracic extension | ≥20° | Limited → adjust swing mechanics |

Prevention centers on neuromuscular control, progressive loading, and aligning the swing with the player’s anatomy. Key elements: rotator cuff endurance progressions,serratus anterior and lower trapezius strengthening,targeted thoracic mobility,and coupling with lower‑body power work to prevent compensatory shoulder torques. When observable biomechanical drivers persist, equipment and technique adjustments (shaft flex, swing arc or grip width) provide secondary prevention. Educating players to detect early symptoms and to manage practice volume helps reduce repetitive microtrauma that commonly contributes to shoulder complaints.

Rehabilitation should move through staged,objective goals from symptom modulation to sport‑specific restoration: (1) acute control-pain and inflammation management plus ROM restoration; (2) motor retraining-reestablish scapular rhythm and eccentrically focused cuff work; (3) strength/endurance-progressive overload with emphasis on muscular endurance at moderate loads; (4) return‑to‑swing-graded reintroduction of impact,tempo and full practice.Practical return criteria include pain‑free full ROM, ≥90% strength symmetry on functional tests, normalized scapular mechanics during sport‑specific drills, and clinician‑observed swing mechanics without trunk/shoulder compensation.

| Phase | Primary Goals | Objective criteria |

|---|---|---|

| Acute | Pain control, restore ROM | Pain ≤2/10; ROM within 80% |

| Retraining | Scapular timing, neuromuscular control | No winging on 20 reps |

| Strength | Endurance & resilience | ≥90% ER/IR symmetry |

| Return | Sport‑specific tolerance | Full swing without pain; clinician clearance |

cardiorespiratory and Metabolic Demands of On‑Course Performance: Conditioning, Fatigue resistance and Recovery Tactics

Profiling shows golf to be an intermittent activity dominated by low‑to‑moderate steady‑state effort (walking and course navigation) interspersed with short, intense neuromuscular bursts (the swing and rapid adjustments). Energy for prolonged walking depends primarily on aerobic oxidative metabolism, whereas repeated maximal swings and rapid repositioning transiently recruit phosphocreatine and glycolytic pathways. Heart‑rate typically rises modestly during play with brief spikes at shot execution; this mixed metabolic demand means conditioning should bolster both aerobic capacity and short‑duration power endurance.

Effective conditioning blends an aerobic base with brief, golf‑specific high‑intensity intervals and strength/power work so that swing speed can be preserved under fatigue.Practical emphases include: endurance to support walking and decision‑making across a round, interval‑style power endurance to mimic repeated swing demands, and strength work to sustain force transmission through the kinetic chain.implementation examples include steady low‑intensity aerobic sessions for volume, HIIT protocols for metabolic adaptability, and ballistic resistance circuits to maintain rate‑of‑force development.

- Aerobic base - 30-60 minutes at low-moderate intensity to improve walking economy and between‑shot recovery;

- HIIT / repeat‑effort – short (15-60 s) high‑effort bouts with partial recovery to enhance lactate handling and repeated‑swing resilience;

- Power‑endurance – circuit or cluster sets with light‑moderate loads to protect clubhead speed late in rounds.

Fatigue management and recovery should be data‑informed and individualized. Combine objective monitoring (HRV, session‑RPE, simple on‑range performance checks) with nutritional periodization-timely carbohydrate intake during long rounds and adequate protein for repair-and hydration strategies tuned to environmental demands. Recovery tools from active cool‑downs and mobility sessions to sleep optimization and short contrast exposures are useful when placed into a periodized plan that reflects competition timing.

| Metric | Practical Target | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Aerobic threshold | Sustain moderate HR zone for 30-60 min | Supports walking economy and recovery between holes |

| Repeat‑sprint capacity | 4-8 × 20-40 s high efforts | Simulates repeated high‑power demands during play |

| Sleep duration | 7-9 hours nightly | Optimizes cognitive recovery and physiological restoration |

Neuromuscular Control, Motor Learning and Skill Transfer: Coaching cues and Practice Structures that Stick

Elite golf performance is built on precise sensorimotor coordination rather than isolated strength alone.Reliable swings come from well‑timed intermuscular recruitment,correct sequencing,and rapid modulation of force-a blend shaped by peripheral changes (better RFD and stretch‑shortening efficiency) and central adaptations (improved anticipatory postural adjustments and internal models). Training that targets timing-tempo drills,reactive balance challenges and variable‑load speed work-promotes the neural specificity needed for consistent ball‑striking and trajectory control. Introducing controlled perturbations helps athletes develop motor solutions that remain effective when environmental conditions vary on the course.

Motor learning literature indicates lasting enhancement stems from practice that encourages problem solving and strong memory traces. Coaching tactics that favor an external focus, limit heavy explicit technical instruction during initial learning, and employ analogy‑based cues enhance implicit learning and transfer under pressure. Practical cue examples include:

- External focus: “Feel the clubhead sweep along your target line”;

- Analogy: “Release like a coiled spring”;

- Outcome focus: “See the ball land where you want it”;

- Self‑controlled feedback: let learners request video or shot feedback when thay prefer.

Design practice by balancing repetition with variability to maximize retention and transfer. Distributed sessions with interleaved variability (contextual interference) produce smaller immediate gains but stronger long‑term retention; therefore alternate blocks of focused technical work with game‑like, variable scenarios. Reduce augmented feedback over time to foster internal error detection. Late in training, add dual‑task and pressure simulations to train attentional control and resilience. A practical plan combines short quality sessions for motor refinement plus longer, varied sessions for strategic application.

Close the training loop with retention probes (24-72 hours and 1-4 weeks) and transfer tests (on‑course performance or simulated competition) to verify that neuromuscular and technical gains persist. A compact template for practice modes and expected retention outcomes can guide microcycle planning:

| Practice Format | Primary Aim | Retention Expectation |

|---|---|---|

| Blocked technical reps | Refine kinematics | Short‑term improvement |

| Interleaved variability | Build adaptability | Stronger long‑term retention |

| Simulated competition | Stress transfer | Improved on‑course application |

Pair these practice structures with targeted neuromuscular conditioning-plyometrics for RFD and rotational strength for sequencing-and schedule regular retention checks to confirm physiological improvements manifest as stable, transferable golf skills.

Integrated Periodization and Load Management for Golfers: Individualization, Monitoring and Return‑to‑Play

Periodization for golf should be treated as a coordinated system aligning biomechanical demands, physiological capacities and the competitive calendar. Integrated periodization sequences stress and recovery across micro‑, meso‑ and macrocycles to develop rotational power, proximal‑to‑distal sequencing and multi‑day endurance while protecting vulnerable structures such as the lumbar spine and lead shoulder.

Individualization is essential: golfers differ in age, body shape, training background, injury history and technical style. Assessment‑driven prescriptions should determine progression. Critically important inputs include:

- Performance profile: swing kinematics, clubhead speed and sequencing;

- Physiological profile: strength/power testing, aerobic capacity and tissue load tolerance;

- Contextual modifiers: event schedule, travel, psychosocial stressors and equipment changes.

Monitoring blends external and internal load measures so daily and weekly adjustments are evidence‑based. External load tracks work performed (swings, practice volume, distance walked); internal load captures the athlete’s response (session‑RPE, HRV, pain scores). the table below lists practical metrics and sample decision thresholds to manage practice-adapt thresholds to the individual athlete:

| Metric | Type | Sample guidance |

|---|---|---|

| Session‑RPE × duration | Internal load | Keep weekly change <10% |

| Number of high‑intent swings | External load | Progress 5-10% per week |

| HRV / resting HR | Recovery metric | Acute declines → increase recovery |

| Pain and movement quality | Clinical | Maintain zero‑to‑low symptoms for progression |

Return‑to‑play should be criterion‑based, staged and conservative relative to the player’s competitive demands.Rehabilitation, reintegration and performance phases need objective benchmarks before advancement. Typical RTP criteria:

- Symptom control: minimal or no pain during sport‑specific tasks;

- Strength and power symmetry: acceptable asymmetry margins for rotational and lower‑limb force output;

- Load tolerance: ability to sustain target weekly high‑intent swing volumes and walking without adverse reaction;

- Movement quality: consistent swing mechanics under fatigue.

A multidisciplinary, evidence‑based decision shared by coach, clinician and athlete should conclude RTP, followed by conservative ramping and ongoing monitoring to minimize re‑injury risk and optimize long‑term performance.

Q&A

Below is a concise,practitioner‑oriented Q&A on the biomechanical and physiological foundations of golf fitness.Background definitions draw on foundational biomechanical literature.

Q1. What is biomechanics and why is it relevant to golf fitness?

A1.Biomechanics applies mechanical principles to living systems to describe movement and the forces that create it. In golf, biomechanical analysis evaluates how body‑segment motions (kinematics), forces and moments (kinetics), and neuromuscular sequencing produce an efficient swing. This perspective helps connect technique,strength,mobility and coordination to both performance and injury risk,guiding evidence‑based training and rehabilitation.

Q2.Which biomechanical variables most directly influence golf performance?

A2. Critical factors are segmental kinematics (trunk, pelvis, shoulder and arm rotation angles and angular velocities), the timing of segmental rotations (the kinematic sequence), ground reaction forces and their timing, joint moments (notably hips, trunk and shoulders), and clubhead speed at impact. These collectively determine ball speed, launch conditions and dispersion while indicating mechanical loads that affect injury risk.

Q3. What physiological capacities underpin an effective golf swing?

A3. Key physiological qualities include maximal muscular strength (hip, posterior chain, trunk and shoulder stabilizers), power and RFD to produce rapid club acceleration, muscular endurance to maintain technique across rounds, joint mobility (thoracic and hip rotation) for optimal swing geometry, and neuromuscular coordination/proprioception for precise timing.

Q4. Which anatomical regions and muscle groups matter most?

A4. Priority regions are the hips and gluteal complex (force generation and pelvis control), the lumbar‑pelvic complex plus deep trunk stabilizers (force transfer and spinal protection), the thoracic spine and scapular stabilizers (rotational ROM and shoulder health), rotator cuff and periscapular muscles (shoulder control), forearm/wrist musculature (grip and clubface control), and the lower limb muscles (quads, hamstrings, calves) for GRF production and stability.

Q5. How does the kinematic sequence relate to training?

A5. A proximal‑to‑distal sequence (pelvis → thorax → arms → club) optimizes angular momentum transfer and can achieve high clubhead speeds with lower joint stress when performed efficiently. Training therefore targets coordinated timing (motor‑control drills), rotational power (med‑ball throws, resisted rotation) and mobility/stability to permit correct sequencing.

Q6. What assessment tools quantify biomechanical and physiological factors?

A6. Tools range from 3D motion capture,force plates and EMG to high‑speed video,dynamometry and jump/throw testing for strength and power. Field‑friendly options include wearable inertial sensors,club sensors and standardized mobility/stability screens.

Q7. How do you convert biomechanical insight into training?

A7. Follow specificity, progression and individualization. Strengthen the hip and posterior chain; use plyometrics and rotational med‑ball drills for RFD; implement thoracic, hip and shoulder mobility plus neuromuscular control exercises; practice segmented drills progressing to full‑speed swings; and periodize skill, strength and power phases to peak for competition while controlling fatigue.

Q8. How do biomechanics and physiology inform injury prevention?

A8. Biomechanics pinpoints problematic motions and loading patterns (e.g., excessive lumbar shear or early extension). Physiological preparation-strengthening stabilizers, improving mobility and endurance-increases tissue capacity.combined with load management and technique modification, these strategies reduce cumulative injury risk for the low back, shoulder and elbow.

Q9. What effect does fatigue have and how can it be managed?

A9. Fatigue impairs neuromuscular timing and force output, frequently enough producing compensatory kinematics and higher joint loads. Manage fatigue with targeted endurance and resistance training of playing muscles, on‑course pacing, nutrition and hydration strategies, scheduled recovery and objective load monitoring (session‑RPE, performance markers, HRV).

Q10. Why is rate of force development (RFD) critically important and how is it trained?

A10. As the swing requires very fast force production over short durations, RFD is critical. Train it with ballistic lifts, plyometrics, Olympic‑style movements performed with intent, and sport‑specific rotational power drills. Assess with jump/throw tests or force‑plate RFD measures.

Q11. How are lab findings translated to on‑course coaching?

A11. Prioritize the few biomechanical deficits most linked to a player’s performance or injury profile, design clear, task‑specific drills that mimic swing demands, use accessible feedback (video, tempo devices), and progressively integrate corrected mechanics into full‑speed, game‑like practice. Collaboration between coaches, S&C professionals and biomechanists enhances translation fidelity.

Q12. What limitations exist and what should future research address?

A12. Challenges include inter‑individual variability in optimal technique, a shortage of longitudinal intervention trials linking specific prescriptions to long‑term outcomes, and hurdles in translating lab data to field use.Future work should prioritize individualized musculoskeletal models, controlled longitudinal training studies, validation of wearable sensors for field biomechanics, and integrated physiological‑biomechanical load monitoring.

References and background sources

Foundational discussions of biomechanics and its application to human movement and sport provide context for the concepts summarized here.

Concluding summary

An evidence‑informed golf‑fitness strategy weaves biomechanical analysis (to identify movement and loading patterns) with targeted physiological conditioning (to raise strength, power, mobility and endurance). This combined pathway enhances the player’s capacity to generate, transmit and tolerate forces necessary for efficient, repeatable swings while lowering injury risk. Practically,use objective assessment (video/marker capture,wearables),physiological testing (strength,power,mobility,aerobic/anaerobic profiles and fatigue monitoring) and individualized periodization to guide interventions. Emphasize mobility and motor control early,build strength and power progressively,and preserve on‑course performance through sport‑specific endurance and recovery practices. Future research and cross‑disciplinary collaboration-spanning biomechanics,exercise physiology,sports medicine and coaching science-will refine best practices and scale assessment tools so that coaching and rehabilitation remain both safe and highly effective.

Swing science: The Biomechanics & Physiology Behind Peak Golf Performance

Headline Options & Tone – pick one and I’ll refine

Below are the 10 headline options you provided, grouped by suggested tone. Pick a tone (scientific, practical, catchy) and a headline and I’ll refine it further for SEO, blog, or newsletter use.

- Scientific tone

- 1. swing Science: the Biomechanics and Physiology behind Peak Golf Performance

- 2. The Science of the Perfect Swing: Biomechanics and Physiology for Golf Fitness

- 7. The Athlete’s Guide to Golf: Foundations of Biomechanics and Physiology

- Practical tone

- 3. Move Better, Swing Further: Biomechanical & Physiological Keys to Golf Fitness

- 5. Golf Fitness Decoded: How Body Mechanics and Conditioning Improve Your Swing

- 6. Swing Smarter: using Biomechanics and Physiology to boost Golf Performance

- Catchy / marketing tone

- 4. power, Precision, Endurance: Unlocking Golf Fitness Through Movement Science

- 8. Optimal Swing, Lower Injury Risk: A Biomechanics-Based Blueprint for Golfers

- 9. Body, swing, Endurance: A Science-Backed Approach to Golf Fitness

- 10. Engineered to Swing: The Physiological and Biomechanical Secrets of Better Golf

Why biomechanics and physiology matter for golf performance

Golf is a technical sport where small improvements in movement quality translate to measurable gains in distance, accuracy, and consistency. Combining biomechanics (how the body moves) with exercise physiology (how the body produces force and energy) gives a blueprint for targeted golf training. Using evidence-based golf fitness principles improves swing mechanics, increases clubhead speed, enhances endurance during a round, and reduces common injuries (low back, shoulder, elbow).

Key biomechanical principles of the golf swing

Kinematic sequence – the engine of an efficient swing

An effective golf swing follows a proximal-to-distal kinematic sequence: pelvis → torso → arms → club. This sequential activation allows energy to be transferred and amplified. Disruptions (early arm firing, limited hip rotation, or poor balance) reduce clubhead speed and increase strain on smaller structures like the elbow and shoulder.

stability vs. mobility – the movement balance

- Hips & thoracic spine mobility: allow rotation without compensatory lumbar movement.

- Core stability: resists unwanted trunk flexion/extension and allows force transfer.

- Scapular control & shoulder mobility: support a full,repeatable backswing and follow-through.

- Lower limb stability: provides a stable base for rotation and weight shift.

Force application & ground reaction

Ground reaction force (pushing through the feet into the ground) is essential: better sequencing + stronger, faster hip extension increases compressive and rotational forces available to the clubhead. Training should focus on improving force production against the ground and coordinating that force into rotation.

Physiology: energy systems & physical qualities for golf

Primary physical qualities

- Rotational power: short-duration, high-intensity efforts drive clubhead speed.

- Maximal and explosive strength: hip, posterior chain, and core strength underpin distance.

- Muscular endurance: maintains swing mechanics through 18 holes.

- Cardiovascular fitness: supports recovery between holes and during walking rounds.

- Versatility & joint range: enable full backswing and follow-through without compensation.

Energy systems used in golf

Golf relies primarily on the phosphagen system (ATP-PCr) for individual swings (0-10 seconds) but also uses the aerobic system across a round for recovery and sustained concentration. Conditioning programs should therefore include short high-power efforts plus low-to-moderate intensity aerobic work for recovery capacity.

Assessment & screening for a golf-specific plan

Before prescribing exercises, assess movement quality and physical capabilities. Common screens include:

- Overhead squat or single-leg squat – lower limb mechanics and core stability

- Thoracic rotation screen – usable rotational range

- Hip internal/external rotation and single-leg stance – hip mobility and control

- Rotational power test (medicine ball throws) – functional power for swing

- Movement with club in hand (golf-specific hinge and rotation) – sport transfer

Evidence-based training components for golf fitness

Mobility & joint preparation

- Dynamic thoracic rotations with a club or dowel

- Hip CARs (controlled articular rotations) and 90/90 hip switches

- Reactive ankle mobility drills for balance and weight shift

Core stability & anti-rotation

- Pallof presses (band anti-rotation) to improve trunk stiffness

- Half-kneeling chops and lifts to build anti-rotation with hip integration

- Dead-bug progressions for coordinated breathing and core timing

Strength & power

- Hip-dominant lifts: Romanian deadlifts, glute bridges (build hip extension)

- Single-leg RDLs and split squats (transfer to unilateral balance and stability)

- Rotational power: medicine ball rotational throws and slams

- Olympic-style derivatives as appropriate (power cleans, kettlebell swings) for explosive hip drive

Conditioning & endurance

- Interval walking or tempo runs to raise aerobic capacity for recovery between holes

- Short high-intensity intervals (10-30s) to train the phosphagen and glycolytic contribution

- Golf-specific circuits combining mobility, balance, and power movements

Flexibility & recovery

- Active stretching post-practice: thoracic rotations, hip flexor lengthening

- Soft tissue work (foam rolling, instrument-assisted soft tissue) to manage load and restore range

Sample weekly golf fitness microcycle (beginner-intermediate)

| Day | Focus | Sample Session |

|---|---|---|

| monday | Strength (Lower / Hips) | Squat/SL RDL, glute bridge, core anti-rotation (45-60 min) |

| Wednesday | Mobility & Power | Thoracic drills, med-ball rotational throws, mobility flow (30-45 min) |

| Friday | Strength (Upper / Core) | Rows, push variations, Pallof presses, single-arm carries (45-60 min) |

| Saturday | Golf Practice / On-course | Range session + walking 9-18 holes (variable) |

| Optional | Conditioning | 20-30 min brisk walk or interval session for recovery |

Injury prevention & load management

Common golf injuries occur from repetitive forces and poor mechanics. Strategies to reduce injury risk:

- Prioritize thoracic mobility to avoid excessive lumbar extension during swing.

- Build hip strength and control to prevent compensatory loading on knees and low back.

- Progress swing volume gradually-monitor range sessions and practice frequency.

- Include pre-round warm-ups that combine mobility, activation, and 2-4 warm-up swings.

- Use objective load metrics where possible (practice minutes, number of swings) and rotate clubs during practice to reduce repetitive stress.

practical drills that transfer to the course

- Step-and-rotate drill: Step into a golf stance from the lead foot and rotate through the shot to rehearse weight transfer and sequencing.

- Medicine ball side throw: From athletic stance, explosive rotation and throw to build rotational power and coordination.

- Pallof-to-rotate: Anti-rotation press followed by a controlled rotation to build torso stiffness then dynamic rotation.

- Half-kneeling woodchop: Integrates hip drive, core control, and shoulder path for better swing mechanics.

- Balance-to-swing: Single-leg stance holds followed by small swings to train balance during the dynamic motion.

Case study snapshot: recreational golfer to consistent gains

Player: 45-year-old recreational golfer, 12-handicap, limited thoracic rotation, complaints of lower-back tightness after 9 holes.

Intervention over 12 weeks:

- Weeks 0-4: Mobility & core stability (daily 10-15 minute routines), 2x/week strength (focus on hip hinge)

- Weeks 5-8: Add rotational power work (med-ball throws), progress strength loads

- Weeks 9-12: Integrate golf-specific circuits and increase on-course practice volume

Outcome: 10-12% increase in measured rotational power, reduced back tightness, improved consistency and clubhead speed. This example highlights how targeted training addressing mobility, core stiffness, and hip power transfers to measurable swing improvements.

SEO-tailored headline and meta suggestions (pick context)

Choose one context and copy/paste the matching headline + meta to your CMS:

SEO-optimized (search-focused)

Headline: Move Better, Swing further: Biomechanical & Physiological Keys to Golf Fitness

Meta title: Move Better, Swing Further – Golf Fitness & Biomechanics for Distance

Meta description: Improve your golf swing with proven golf fitness strategies: biomechanics, mobility, strength, and injury prevention tips for more distance, accuracy, and endurance.

Blog post (engaging, long-form)

Headline: Swing Smarter: Using Biomechanics and physiology to Boost Golf Performance

Meta title: Swing Smarter – Biomechanics & Physiology Tips for Better Golf

Meta description: learn how biomechanics and physiology inform golf fitness programs. Practical drills, sample training plans, and injury prevention strategies for golfers of all levels.

Newsletter headline (short & clickable)

Headline: Engineered to Swing: Unlock More Distance with Smart Golf Fitness

Meta title: Engineered to Swing - Speedy Golf Fitness Wins

Meta description: Quick, actionable golf fitness tips to boost clubhead speed, improve mechanics, and lower injury risk-perfect for your next round.

Practical tips for implementation

- Track practice swings and time on-course to manage load-aim to increase swing volume by no more than 10% per week.

- Prioritize quality movement over quantity: better mechanics with fewer swings beats poor mechanics with more swings.

- Combine on-course practice with targeted gym sessions (2-3 sessions per week) for the best transfer to play.

- Periodize training: build mobility and base strength off-season, increase power and on-course specificity closer to peak play.

- use technology wisely-launch monitors and wearable sensors can give objective feedback on clubhead speed and sequencing for progressive improvements.

Need help picking one headline or building a post?

Tell me which tone you wont (scientific, practical, catchy) and whether the piece is for SEO, a blog, or a newsletter.I’ll refine the headline, meta tags, and provide a tailored 600-1200 word draft or a social media blurb to match.