The golf swing is a complex, high‑velocity motor task in which precise coordination of multisegmental kinematics, temporally sequenced muscle activation, and efficient intersegmental force transfer determine both performance outcomes and injury risk. As competitive and recreational play increasingly emphasize measurable performance metrics-clubhead speed, ball launch conditions, and accuracy-understanding the underlying mechanical and neuromuscular determinants of swing efficacy has become essential for players, coaches, and clinicians. Concurrently, the prevalence of overuse and acute injuries related too suboptimal technique underscores the need to translate biomechanical insight into preventative and rehabilitative strategies.Biomechanics, broadly defined as the application of mechanical principles to biological systems, provides the conceptual and methodological framework to analyze the golf swing (see, e.g., foundational treatments of biomechanics). Applied to golf, this framework encompasses kinematic analyses of joint angles and segmental sequencing; kinetic assessments of ground reaction forces, intersegmental moments, and club-shaft interactions; and neuromuscular investigations of timing, intensity, and coordination of muscle activation. Integrating these domains enables quantification of how mechanical energy is generated,transferred,and dissipated across the body-club system and how variations in technique,physiology,or equipment alter performance and tissue loading.This article synthesizes current knowledge on the biomechanical principles that govern swing mechanics and outlines evidence‑based opportunities for optimization. We review joint kinematics across the lower extremity,torso,and upper limb; examine muscle activation patterns that produce and modulate rotational power; and describe force transfer mechanisms-including the roles of ground reaction forces,pelvic-thoracic dissociation,and the kinetic chain-in shaping clubhead outcomes. Methodological approaches such as three‑dimensional motion capture, force platform analysis, musculoskeletal modeling, and electromyography are discussed with attention to thier respective strengths and limitations for both research and applied settings.

we translate biomechanical findings into practical recommendations for technique modification, training interventions, and injury prevention, and we identify persisting gaps in the literature where future experimental and modeling work could most effectively improve performance and athlete safety. By linking basic mechanical principles to applied optimization strategies, this review aims to inform coaches, practitioners, and researchers seeking to enhance swing efficiency while minimizing musculoskeletal risk.

Biomechanical Foundations of the Golf Stance and Address: Posture, Joint Alignment, and Recommended Adjustments

Postural integrity at address begins with a coordinated hip hinge and a neutral spinal column that together create a stable mechanical platform for the swing. The optimal stance locates the athlete’s center of mass over the mid-foot, establishing a balanced base without excessive anterior or posterior weight bias. Biomechanically, this alignment minimizes compensatory motions in the lumbar and thoracic segments during weight transfer and allows elastic energy to be stored and released through controlled rotation rather than linear sway. Emphasis should be placed on maintaining vertebral alignment in the sagittal plane while permitting an intentional forward inclination from the hips.

Specific joint orientations at address establish the angular relationships that determine kinematic sequencing during the swing.The table below summarizes practical address targets derived from functional biomechanics and coaching norms for the recreational-to-advanced player:

| Joint | Typical Address Range | Coaching Cue |

|---|---|---|

| Ankle | ~5-15° dorsiflexion | Weight centered over mid-foot |

| Knee | ~10-20° flexion | Soft, not locked; reactive for rotation |

| Hip | ~20-30° hinge (flexion) | Hinge from hips, maintain neutral spine |

| Spine | Neutral with an intentional forward tilt | Chest over ball, shoulders behind hands |

Pelvic position and core engagement are primary drivers of reproducible postural control.A slight anterior pelvic tilt to create hip hinge without lumbar flexion preserves intervertebral spacing and reduces the loading on posterior ligaments. Functional cues that have empirical support include: “hinge from hips,” “brace the core lightly,” and “maintain a long thoracic spine.” Practical on-course reminders can be distilled into short motor cues delivered promptly prior to address to promote consistent muscle activation and to limit undesirable lumbar rounding.

Upper-extremity alignment and relaxed tension at address directly influence clubface control and early swing sequencing.Biomechanically efficient address positions allow the arms to hang from the shoulder girdle with minimal elbow flexion and a neutral scapular posture-this promotes an appropriate shaft-plane relationship and elastic loading across the torso. Recommended adjustments include maintaining moderate grip pressure (avoid >5/10 on subjective scale), ensuring the lead shoulder is slightly lower than the trail shoulder when targeting a neutral swing plane, and using the natural arm hang to set the clubshaft angle rather than forcing wrist extension.

When deviations are present, targeted corrective strategies restore biomechanical efficiency. Common faults and adjustments:

- Excessive lumbar flexion: wall hinge drill to re-learn hip dominant bending.

- Too upright (insufficient hip hinge): alignment rod placed along spine to practice forward tilt without rounding.

- Weight too far forward/back: balance-to-midfoot drill – swing with eyes closed for 5-10 reps to internalize weight distribution.

- High grip tension: progressive relaxation sets; squeeze-release protocol between shots.

Consistent monitoring using video or mirror checks combined with short, reproducible pre-shot cues will translate these biomechanical recommendations into durable postural habits.

Kinematic Sequencing and the Kinetic Chain: Optimizing Temporal Coordination for Maximum Clubhead Speed

Temporal coordination in the golf swing is best conceptualized as a sequenced cascade of segmental rotations where proximal segments initiate motion and distal segments amplify velocity through coordinated timing. This proximal-to-distal pattern-pelvis → thorax → lead arm → club-maximizes transfer of angular momentum while minimizing energy dissipation. Distinguishing kinematic descriptions (motion trajectories, angular velocities, temporal ordering) from dynamic analyses (forces, torques, ground reaction) clarifies evaluation: kinematic sequencing describes the ”when” and “how fast,” while dynamics explain the “why” in terms of force generation and transmission.

Efficient energy transfer depends on reproducible timing windows rather than isolated peak magnitudes. Typical high-performance profiles show ordered peaks in angular velocity with small inter-segment delays; deviation from this order or excessive simultaneous peaks reduces clubhead speed and increases dispersion. Key orchestration features include:

- Pelvic rotation - early peak to establish a stable base and create a rotational differential.

- Thorax (upper trunk) – delayed peak that leverages the pelvic lead to build stored elastic energy.

- Lead arm and wrist – late acceleration and controlled release that convert proximal energy into clubhead velocity.

- Club – maximal angular velocity at or immediately before impact; timing relative to wrist release is critical.

Mechanical amplification arises from coordinated segment deceleration and elastic recoil: controlled braking of the thorax and lead arm increases relative motion of distal segments, while tendon-muscle elasticity and appropriately timed ground reaction forces (GRF) augment torque production.The interaction of kinematic timing and GRF is well captured by combining motion capture with force-plate data. The following simple comparative table summarizes representative timing windows (expressed as percentage of the interval from top-of-backswing to impact) used in applied biomechanics to diagnose sequencing faults:

| Segment | Peak angular velocity (typical) | Timing (% to impact) |

|---|---|---|

| Pelvis | Moderate | 75-85% |

| Thorax | High | 85-95% |

| Lead arm/wrist | Very high | 95-100% |

translating diagnostics into intervention requires targeted drills that isolate timing and inter-segment coordination rather than merely increasing muscular effort. Effective exercises emphasize feel of sequential release and controlled deceleration:

- Step-and-rotate drill – promotes synchronized pelvic rotation and early weight shift.

- Closed-chain trunk braking – practice abrupt thorax deceleration to accentuate distal speed.

- Delayed release swings – low-speed repetitions emphasizing late wrist un-cocking and club acceleration.

- Force-plate feedback reps – train GRF timing to coincide with segmental peaks for maximal torque transfer.

From a coaching and assessment perspective, combine kinematic sequencing metrics (angular velocity profiles, inter-segment time-lags) with dynamic measures (GRF, joint moments) to form individualized prescriptions. Expect inter-player variability-anthropometry, flexibility and motor control shape an athlete’s optimal timing pattern-so use normative templates as guides, not absolutes. Prioritize repeatability of the proximal-to-distal order, measurable improvements in inter-segment delay consistency, and the convergence of kinematic and kinetic indicators when judging progress toward greater clubhead speed and shot reliability.

Role of Major Muscle Groups and Electromyographic Insights: Targeted Strength and Activation Strategies

The golf swing is orchestrated by coordinated contribution from distinct muscular regions: the **lower extremity** (gluteus maximus, hamstrings, quadriceps) generates the ground-reaction forces and initiates the proximal drive; the **lumbopelvic and trunk complex** (obliques, rectus abdominis, erector spinae, transverse abdominis) transmits and amplifies rotational momentum; the **scapulothoracic and shoulder muscles** (rotator cuff, latissimus dorsi, pectoralis major) refine club path and apply distal force; and the **distal forearm and intrinsic hand muscles** control wrist angle and impact stiffness. A biomechanically efficient swing depends on both magnitude and timing of these contributions so that energy flows proximally to distally with minimal dissipation across joints.

Electromyographic (EMG) investigations consistently demonstrate a proximal-to-distal activation sequence in skilled golfers, with early and high-amplitude bursts in hip extensors and trunk rotators followed by phased increases in scapular stabilizers and wrist flexors approaching impact. EMG amplitude and onset latency differentiate levels of skill: elite performers show earlier hip/trunk activation, reduced co-contraction in antagonistic pairs during acceleration (improving transfer), and a characteristic pre-impact peak in forearm flexors associated with clubhead speed. These insights highlight that both temporal patterning (onset and sequencing) and intensity (integrated EMG) are critical determinants of performance and injury risk.

Training interventions should therefore prioritize power,rate of force progress,and task-specific motor patterns rather than isolated hypertrophy alone. Recommended emphases include:

- Explosive hip and posterior chain - hip thrusts,jump variations and loaded kettlebell swings to optimize early drive.

- Rotational power – medicine-ball rotational throws and cable chops to reproduce trunk torque timing.

- Scapular and rotator cuff endurance - low-load high-repetition external rotation and serratus anterior activation to stabilize the shoulder through follow-through.

- Forearm and wrist stiffening - eccentrically biased wrist curls and isometric holds to tune impact stiffness.

Each exercise should be progressed with attention to eccentric control and stretch-shortening cycle efficiency to better match EMG profiles observed in skilled swings.

Translating EMG findings into practical activation drills can accelerate neuromuscular learning. The table below summarizes concise drill-to-muscle mappings and target EMG timing cues used in applied programs (values approximate and intended for relative prescription):

| Muscle | Activation cue | EMG Target (approx.) |

|---|---|---|

| Gluteus maximus | “Drive the back hip toward the target” | Onset ~400-300 ms pre-acceleration |

| External obliques | “Rotate hard through chest” | Peak ~200-100 ms pre-impact |

| Rotator cuff | “Set the shoulder and maintain” | Low-level tonic activity throughout; burst at acceleration |

| Forearm flexors | “Grip and hold through impact” | Peak ~50-0 ms pre-impact |

To mitigate injury and optimize long-term adaptations, program design must integrate antagonist balance, eccentric capacity, and periodized neuromuscular loading guided by EMG where available. Rehabilitation and return-to-play criteria benefit from EMG benchmarks (restoration of timing and amplitude symmetry),while chronic training should alternate phases of maximal power,movement-specific tempo,and muscular endurance to preserve shoulder and lumbar health. Ultimately, merging EMG-derived targets with progressive, sport-specific strength work yields measurable improvements in efficiency and a reduction in overload-related injuries.

Ground Reaction Forces and Lower Limb Mechanics: Techniques to improve stability and Power Transfer

Effective transfer of force from the ground into clubhead velocity depends on temporal coordination between lower-limb force production and trunk rotation. Ground-reaction forces (GRFs) exhibit both vertical and shear components that must be modulated across the backswing-to-impact sequence; the typical pattern for skilled players is an early lateral and vertical loading of the trail limb followed by a rapid shift and propulsive spike under the lead limb near impact. Monitoring the timing, magnitude and rate of rise of these components provides objective markers of efficient energy transfer and helps distinguish technique-driven power from strength-driven overswinging. Key metrics to monitor include peak vertical GRF, anterior-posterior shear, and time-to-peak relative to ball contact.

Lower-limb mechanics create the biomechanical platform for those GRF patterns. Optimal force transfer requires coordinated ankle stiffness modulation,knee flexion-extension sequencing and powerful hip extension with controlled internal rotation. Excessive ankle dorsiflexion or early lead-knee collapse dissipates transverse torque, while inadequate hip extension limits proximal-to-distal energy flow. From an anatomical perspective, the posterior chain (gluteus maximus, hamstrings) is primarily responsible for propulsive GRF, whereas the quadriceps and calf musculature provide shock absorption and stabilization-each must be trained to fulfil both concentric and eccentric roles within the swing.

Technical interventions can produce immediate and durable improvements in platform stability and power transfer. Recommended practice elements include:

- Progressive weight-shift drills – emphasize delayed lateral transfer until the downswing transition to maximize trail-limb loading.

- Heel-toe rocker repetitions – teach dynamic ankle-stiffness adjustments and smooth center-of-pressure (COP) progression.

- Resisted rotational pushes – use bands to train hip extension while resisting early upper-body rotation.

- Single-leg RFD training – enhances rate of force development under the lead limb for impact spikes.

Each drill should be cued for COP awareness and timed to the intended swing phase rather than performed in isolation from the swing rhythm.

Exercise programming should integrate strength, power and neuromuscular control with clear progressions. The table below summarizes exemplar interventions, primary targets and simple coaching cues.

| Intervention | Primary Target | Coaching Cue |

|---|---|---|

| Single-leg hop-to-hold | RFD & stability | “Explode, then balance” |

| Band-resisted rotation | Hip extension timing | “Push the ground, rotate later” |

| Slow eccentric squats | Eccentric knee control | “Lower with control” |

Progressions should move from low-load technical drills to higher-velocity, golf-specific movements and eventually to on-course integration under fatigue conditions.

Quantitative assessment refines technique modifications and injury-risk management. Portable force platforms and in-shoe pressure sensors allow measurement of COP trajectory,limb-to-limb GRF symmetry and impulsive loading rates-useful both for baseline profiling and for monitoring adaptation. Clinically relevant thresholds (for example, persistent >10-15% interlimb asymmetry in peak GRF or COP excursion) warrant targeted intervention. combine objective measures with video-based kinematics to link external force patterns to joint-level mechanics; this multimodal approach yields both performance gains and reduced musculoskeletal stress when implemented within a periodized coaching plan.

Torso Rotation, Hip Mobility, and Lumbar Spine Load Management: Balancing Range of Motion and Injury Risk

The coordinated expression of axial rotation between the thorax and pelvis is the mechanical basis for high clubhead velocity and controlled ball flight. A large intersegmental rotation differential-often quantified as the “X‑factor”-permits the trunk to unload angular momentum into the arms and club during transition. However, achieving high rotational ROM without appropriate timing and force transfer compromises efficiency. Kinematic sequencing that promotes early pelvic rotation followed by thoracic acceleration optimizes elastic energy storage in the obliques and lumbar stabilizers, while preserving joint congruency across the lumbopelvic complex.

When hip motion is restricted, the lumbar spine commonly assumes compensatory axial rotation and lateral bending, increasing shear and compressive loads on the intervertebral discs and facet joints. Electromyographic and kinetic studies indicate that insufficient hip internal/external rotation increases eccentric demand on the multifidus and erector spinae, particularly during deceleration after ball impact. These altered load paths raise the probability of cumulative microtrauma; clinically relevant risk factors include asymmetrical hip ROM, hyperlordosis during extension, and repetitive high‑velocity swings without adequate recovery.

Optimization requires a balanced program that preserves necessary rotational range while minimizing harmful spinal moments. Key components include targeted mobility work for the hips and thoracic spine, progressive strengthening of the gluteal complex and deep trunk stabilizers, and motor control drills that retrain pelvis‑thorax dissociation. Practical interventions:

- Hip mobility: dynamic internal/external rotation and loaded end‑range holds.

- Thoracic rotation: quadruped thread‑the‑needle progressions and resisted rotational swings.

- Core control: anti‑rotation plank variations and unilateral deadbug progressions emphasizing eccentric control.

- Sequencing drills: slow‑motion swings with pelvic lead then accelerated thoracic follow‑through.

These elements reduce reliance on lumbar rotation and promote safer force transmission from ground to club.

Effective monitoring and prescription can be supported by simple screening metrics and staged load management. The table below provides concise screening targets and corresponding interventions that bridge clinical assessment with on‑course application.

| Metric | Target | Initial intervention |

|---|---|---|

| Hip IR/ER (squat) | >30° each | SMR + 3×30s dynamic holds |

| Thoracic rotation | >45° seated | Thoracic mobility sets 3×10 |

| Prone core endurance | ≥90 s | Progressive anti‑rotation load |

For coaches and clinicians the emphasis should be on individualized thresholds rather than worldwide maximal rotation.Modify swing mechanics-tempo, depth of turn, and pelvic lead-to respect tissue capacity while preserving performance intent.Use periodized exposure (e.g., technical sessions, reduced‑intensity power work, and recovery days), integrate objective screening into return‑to‑play decisions, and refer persistent pain or neurologic signs for medical evaluation. When applied consistently,these strategies strike a pragmatic balance between maximizing functional range and minimizing lumbar spine injury risk.

Swing faults and Biomechanical Diagnostics: Objective Assessment Protocols and Corrective Interventions

Clinical biomechanical assessment begins with a **standardized protocol** integrating 3D motion capture, inertial measurement units (IMUs), force platforms, and surface electromyography (sEMG). Recommended acquisition parameters include ≥200 Hz for kinematics, ≥1000 Hz for sEMG, and synchronous force data to capture impact-phase kinetics. Reliability is improved by a consistent marker set, repeatable warm-up, and task standardization (full swing with a mid-iron and driver). These methodological details permit reproducible quantification of joint angles, angular velocities, segmental sequencing, and intersegmental timing-forming the objective basis for fault identification and targeted intervention planning.

Typical movement deviations present distinctive biomechanical signatures. For example, **early extension** manifests as premature hip extension with loss of X‑factor and increased lumbar lordosis; **over‑the‑top** is characterized by anteriorly tilted upper torso and an outside‑in club path with delayed pelvis-to-trunk rotation; **casting** shows reduced wrist lag and premature release with diminished peak angular velocity. Concurrent sEMG often reveals compensatory patterns-overactivity of erector spinae in reverse spine angle or underactivation of gluteus medius during lateral sway-helping to differentiate structural mobility deficits from neuromotor control errors.

To translate diagnostics into practice, a concise decision matrix is useful:

| Fault | Objective Metric | Threshold / Indicator | Primary Intervention |

|---|---|---|---|

| Early extension | Hip flexion angle at TOP | Loss >10° vs normative | Glute activation drill + posterior chain mobility |

| Over‑the‑top | Club path (deg) & pelvis‑trunk delay (ms) | Outside‑in >6°; sequencing delay >25 ms | Rotation timing drills + impact alignment cues |

| casting | Wrist extension at P4 & peak angular vel | Premature decrease in wrist lag | Lag retention swings + eccentric wrist strengthening |

Corrective programs should adopt a multimodal, periodized approach that integrates **mobility restoration**, progressive strength/power training, and motor learning‑based swing re‑education. effective strategies include constrained practice (targeted swing constraints to promote desired path),distributed feedback (reduced augmented feedback frequency to encourage retention),and overload/underload implements to modify timing and tempo. Emphasis on transfer is critical: drills must replicate the degrees of freedom, speed, and sensory context of on‑course swings to ensure ecological validity.

Implementation requires iterative monitoring and predefined progression criteria. Baseline testing establishes objective targets; periodic reassessment (e.g., 4-8 week cycles) tracks changes in kinematics, kinetics, and EMG. Safety and injury prevention should guide intensity and exercise selection, particularly when lumbar or shoulder deficits are detected. useful monitoring metrics include:

- Peak pelvis‑trunk rotational velocity

- Sequencing latency (pelvis→thorax→club)

- Ground reaction force symmetry

- sEMG timing of prime movers

Integrating Technology and Quantitative Feedback: Using Motion Capture, Force plates, and Wearables for Performance Optimization

Quantitative instrumentation reframes the golf swing as a coupled kinematic-kinetic system that can be measured, modeled and optimized. High-fidelity **motion-capture** systems provide three-dimensional joint angles,segment velocities and club kinematics; when combined with inverse dynamics they reveal joint torques and segmental power contributions. Interpreting these outputs requires attention to **sampling frequency**, marker protocol, and model degrees of freedom so that inter-session reliability and between-player comparisons remain valid for training prescription and biomechanical research.

Force plates quantify ground reaction forces and center-of-pressure trajectories, producing direct evidence of weight-transfer strategies and lower-limb contribution to angular momentum. Synchronized kinetic and kinematic streams permit calculation of rate-of-force-development, impulse phases, and timing of peak vertical and horizontal force relative to club-head acceleration. These kinetic markers are critical for differentiating effective sequencing from compensatory patterns-guiding targeted interventions in strength, mobility or technique to improve **transfer efficiency** and reduce injury risk.

Wearables extend laboratory measures into practice and competition by providing continuous,context-rich feedback on tempo,segmental angular velocity and physiological load. Key actionable outputs include:

- tempo/Duration metrics (backswing:downtempo ratios)

- Peak angular velocities for pelvis and thorax

- Load indicators (HRV, fatigue proxies) to modulate practice intensity

| technology | Primary outputs | Recommended sampling |

|---|---|---|

| Optical motion capture | Joint angles, club path | 240-1000 Hz |

| Force plates | GRF, COP, impulse | 1000 Hz |

| Wearables (IMU/HR) | Angular velocity, tempo, HR | 50-500 Hz |

Integrative analysis requires precise synchronization and signal processing: time-alignment (hardware trigger or cross-correlation),filter selection (zero-lag Butterworth or wavelet denoising),and normalization strategies (body-size or mass-based) are essential to produce interpretable metrics. Statistical techniques-within-subject repeated measures, principal component analysis of kinematic patterns, and mixed-effects models-translate raw signals into robust indicators of performance change and individual response variability. Emphasis on **effect sizes** and minimal detectable change aids clinicians and coaches in distinguishing meaningful adaptation from measurement noise.

Practical application couples measurement with closed-loop feedback to accelerate motor learning: real-time auditory or haptic cues tied to target metrics (e.g., pelvic rotation velocity or weight shift timing) produce immediate error augmentation and faster retention than verbal instruction alone. A protocol-driven approach-baseline assessment, targeted drills informed by device outputs, and progressive load management guided by wearable-derived fatigue markers-creates an evidence-based pathway to improve club-head speed, shot dispersion and resilience while minimizing overuse. The result is a reproducible, quantitative roadmap for individualized performance optimization grounded in biomechanical principles.

evidence Based Training Programs and Drills: Progressive Strength, Mobility, and Motor Control Recommendations for Skill Transfer

Contemporary training for the golf swing adopts a staged, evidence-informed progression that links physiology to on-course performance: systematic restoration of mobility, development of force and power, and refinement of motor control to facilitate skill transfer. Programs should prioritize task specificity and progressive overload while maintaining movement quality; this ensures adaptations in strength and coordination are expressed as greater clubhead speed, improved shot dispersion, and reduced injury risk. **Integration across domains**-mobility, strength, and neuromotor training-rather than isolated blocks, produces the most reliable transfer to swing mechanics when exercises are selected to mirror kinematic and kinetic demands of the swing.

Mobility work targets segments that constrain the kinematic sequence: thoracic rotation, hip internal/external rotation, glenohumeral range, and ankle stability. Start with baseline screening (e.g., seated trunk rotation, Thomas test, 90/90 hip) and progress from active, tissue-amiable interventions to loaded end-range control. Example drill emphases include:

- Dynamic thoracic rotation with band-assisted rib pull (3×8-10 reps per side)

- Hip capsule loader-controlled 90/90 rotations emphasizing posterior chain tension (2-3 sets)

- Ankle dorsiflexion chaining through slantboard and single-leg reach tasks (progress to perturbations)

Strength and power phases should be organized around movement patterns that dominate the swing: anti-rotation/bracing, triple-extension transfer, and rotational power. Use a periodized template: foundational hypertrophy/technique (6-12 weeks, 6-12 reps), strength consolidation (3-6 weeks, 4-6 reps), and power conversion (3-5 weeks, 1-6 reps, high velocity). Emphasize multi-planar, high-intent lifts-medicine ball strikes, loaded rotational RDLs, and horizontal push/pull variations. Recovery, eccentric control, and posterior-chain resilience (glute-ham emphasis) are essential to reduce overuse injuries and preserve swing mechanics under fatigue.

Motor control training should apply principles of variability and contextual interference to accelerate robust skill acquisition: alternating blocked and randomized practice, interleaving short technical cues with full-speed swings, and privileging an external focus of attention (e.g., ball-target dynamics). Augmented feedback is most effective when faded: frequent feedback during early acquisition, reduced frequency for consolidation, and delayed summary feedback for retention. Practical drills include alternating tempo over/under practice, constrained swing paths that exaggerate pelvis-trunk separation, and randomized distance tasks that demand graded force output and decision-making.

Periodization and monitoring close the loop: schedule microcycles that alternate higher-load gym sessions with technique-dominant, lower-load on-deck work; taper power loads before competition while preserving neuromuscular readiness. Use simple objective benchmarks-clubhead speed, peak pelvis-trunk angular velocity differential, and single-leg hop symmetry-alongside subjective readiness scales. The following concise progression table outlines a sample three-phase microcycle ladder for quick program design:

| Phase | Primary Focus | Example Drill |

|---|---|---|

| Restore | Mobility & control | T-spine band rotations |

| Build | Strength & resilience | Loaded rotational RDLs |

| Convert | Power & transfer | Med ball overhead throws to target |

Q&A

Q1: What is biomechanical analysis and why is it relevant to the golf swing?

A1: Biomechanical analysis applies mechanical principles to human movement to quantify how forces, torques, and motions are produced and transferred by the musculoskeletal system (see general definitions in biomechanics literature).For the golf swing, biomechanical analysis identifies the kinematic sequence, force generation, and neuromuscular strategies that underpin clubhead velocity and accuracy, thereby informing technique optimization, conditioning, equipment fitting, and injury prevention.

Q2: What are the primary mechanical goals of an effective golf swing?

A2: The primary mechanical goals are to generate maximal controllable clubhead speed at impact while minimizing unwanted variability in clubface orientation. Achieving these goals requires efficient ground-reaction force utilization, coordinated proximal-to-distal angular velocity sequencing of pelvis, trunk, and upper limbs, and precise timing of muscle activations to control the club path and face angle.

Q3: what is the proximal-to-distal kinematic sequence and why is it vital?

A3: The proximal-to-distal sequence describes the temporal ordering in which larger, proximal segments (hips/pelvis) initiate rotation followed by the trunk, shoulders, arms, and finally the club. This sequence allows transfer and amplification of angular momentum, producing higher distal segment velocities (clubhead speed) with reduced metabolic and mechanical cost. Disruption or reversal of this sequence reduces efficiency and elevates injury risk.

Q4: How do ground reaction forces (GRF) contribute to swing performance?

A4: GRFs provide the external reaction forces that the player uses to generate rotational moments and linear acceleration of the body-club system. Properly timed weight shift and vertical loading/unloading allow conversion of GRF into transverse and sagittal plane torques that enhance pelvis and trunk rotation, contributing directly to clubhead acceleration.

Q5: What is the “X-factor” and how does it effect performance?

A5: The X-factor is the relative rotational separation between the pelvis and the thorax (shoulder line) at the top of the backswing. Greater separation can increase elastic energy storage in torso tissues and increase subsequent trunk rotational velocity during downswing,often increasing clubhead speed. though,excessive X-factor without adequate mobility or motor control can increase lumbar and soft-tissue loading and raise injury risk.

Q6: Which muscles and muscle groups are most critical during the golf swing?

A6: Key contributors include the hip extensors/rotators (gluteus maximus/medius), trunk rotators and stabilizers (obliques, multifidus, erector spinae, transverse abdominis), scapular stabilizers and shoulder rotators (rotator cuff, deltoids), and forearm/wrist musculature for club control. Lower-limb muscles (quadriceps, hamstrings, calf complex) generate and transmit force against the ground.

Q7: How does the nervous system coordinate the swing?

A7: The central nervous system orchestrates a temporally precise pattern of feedforward motor commands and reactive feedback adjustments to stabilize posture, time muscle contractions for the kinematic sequence, and adapt to environmental perturbations. Motor learning principles influence how these patterns are acquired and refined with practice and coaching.

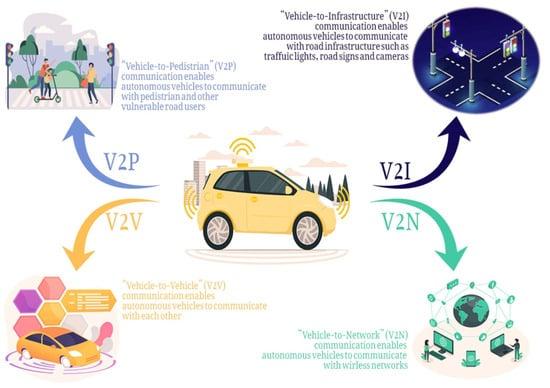

Q8: What measurement technologies are used in golf-swing biomechanics?

A8: Common tools include 3D motion capture (optical marker-based systems), inertial measurement units (IMUs), force plates for GRF, electromyography (EMG) for muscle activation, high-speed video, and instrumented clubs. Computational techniques such as inverse dynamics and musculoskeletal modeling are used to estimate joint moments, powers, and internal loads.

Q9: How are joint kinetics estimated and interpreted?

A9: Joint kinetics (moments, powers) are typically estimated via inverse dynamics using segment kinematics, anthropometrics, and external forces. Interpreting these values helps identify which joints generate versus absorb power during phases of the swing, elucidating efficiency and potential overload sites relevant for performance and injury.

Q10: What common swing faults have biomechanical explanations?

A10: Examples include “early release” (premature wrist unhinging) reducing distal leverage and clubhead speed; “over-rotation” or reverse sequence reducing efficiency; and excessive lateral bending or sliding of the pelvis causing poor contact patterns and increased lumbar shear. Biomechanical analysis links these faults to altered timing, reduced energy transfer, and increased joint loading.

Q11: Which injuries are most associated with the golf swing, and what are the biomechanical contributors?

A11: Low-back pain is the most prevalent, linked to high repetitive rotational loads, lateral bending, and shear forces on the lumbar spine.Other common issues include medial epicondylitis (golfer’s elbow), wrist tendinopathies, shoulder impingement/instability, and knee overload. Contributors include poor sequencing,limited hip/dorsal mobility,inadequate core control,and sudden increases in practice volume.

Q12: What conditioning interventions reduce injury risk while enhancing performance?

A12: Interventions include mobility training (hip and thoracic rotation), trunk and hip strength/endurance (rotational strength, anti-rotation stability), eccentric control for deceleration, and lower-limb power training to enhance GRF use. Progressive workload management, movement pattern retraining, and exercise specificity to the kinematic sequence are essential for transfer to swing performance.

Q13: How can coaching cues be aligned with biomechanical principles?

A13: Effective cues focus on desired outcomes (e.g., “lead with the hips,” “maintain spine angle,” “sequence pelvis before shoulders”) rather than arbitrary positions. Cues should be individualized based on the player’s physical capacities and use external focus and variability to promote robust motor learning consistent with biomechanical aims.

Q14: How does equipment (club design, shaft flex) interact with biomechanical factors?

A14: Club length, mass distribution, shaft stiffness, and grip characteristics influence moment of inertia, timing of release, and vibrational loading on the upper extremity. Optimal equipment fitting considers the player’s swing tempo, strength, and kinematics to maximize energy transfer while minimizing compensatory biomechanics that could increase injury risk.

Q15: What role do computational models and optimization algorithms play?

A15: Musculoskeletal models and optimization algorithms simulate how changes in joint torques, timing, or equipment affect clubhead speed, accuracy, and internal loads.These tools allow hypothesis testing, identification of performance trade-offs, and individualized strategy development, though model validity depends on accurate input data and realistic cost functions.

Q16: What are practical assessment protocols for clinicians and coaches?

A16: A practical protocol integrates functional movement screening (hip/thoracic rotation, single-leg stability), strength/power tests (rotational medicine ball throws, isometric trunk tests), swing kinematics via video or IMUs, and workload tracking. Use of force-plate assessments and targeted EMG is reserved for more advanced or research-oriented assessments.

Q17: How should training be periodized for golfers wanting both performance gains and injury prevention?

A17: Periodization balances phases emphasizing mobility and motor control (off-season),strength and power development (pre-season),and maintenance with technical refinement (in-season). Volume and intensity progression must be individualized, with regular reassessment to adjust training in response to fatigue, pain, or performance metrics.

Q18: What are limitations and common pitfalls in applying biomechanics to coaching?

A18: Pitfalls include overreliance on isolated metrics without considering intersegmental coordination, applying one-size-fits-all technical prescriptions despite individual variability, and interpreting cross-sectional correlations as causal. Measurement error, ecological validity of laboratory tasks, and failure to translate biomechanical feedback into usable coaching cues also limit impact.

Q19: What evidence-based strategies improve transfer from training to on-course performance?

A19: Use task-specific drills that replicate timing and loading patterns, include variability and contextual interference to enhance adaptability, provide augmented feedback that is faded over time, and employ strength/power programs closely matched to swing characteristics. Equipment fitting and fatigue management during tournaments are also critical.

Q20: What are priority research directions in golf-swing biomechanics?

A20: High-priority areas include longitudinal intervention trials linking specific conditioning/coaching approaches to on-course outcomes, development of individualized predictive musculoskeletal models, integration of wearable sensors for ecologically valid monitoring, and machine-learning methods to personalize technique and equipment recommendations. Research should also address mechanisms underlying chronic injury development and recovery.

If you want, I can convert this Q&A into a formatted FAQ for publication, include recommended assessment tests and exercise examples, or create a short bibliography of primary research and review articles on golf-swing biomechanics.

Future Outlook

applying biomechanical principles to the golf swing clarifies how coordinated joint kinematics, temporally sequenced muscle activation, and efficient kinetic‑chain transfer produce both high performance and reduced injury risk. Grounded in the broader discipline that applies mechanics to biological systems and links structure to function (see biomechanics literature), this perspective highlights the importance of tissue mechanical properties, segmental timing, and external force interactions in shaping swing outcomes.

For practitioners and coaches, these insights translate into evidence‑based priorities: refine sequencing to maximize proximal‑to‑distal energy transfer, tailor conditioning to the specific strength and flexibility demands of the trunk, hips, and shoulders, and monitor movement patterns that predispose athletes to overload. For clinicians, understanding the mechanical thresholds of tissues can guide rehabilitation and return‑to‑play decisions to mitigate reinjury.

Future research should emphasize subject‑specific musculoskeletal modeling, longitudinal and field‑based studies, and integration of wearable sensor data with data‑driven optimization techniques to personalize technique and training recommendations. Such approaches will strengthen causal inferences between mechanical variables and performance outcomes and improve translational impact.

Ultimately, a rigorous, biomechanically informed approach-bridging laboratory analysis, applied coaching, and clinical practice-offers the most promising path to optimize the golf swing while safeguarding athlete health and longevity.