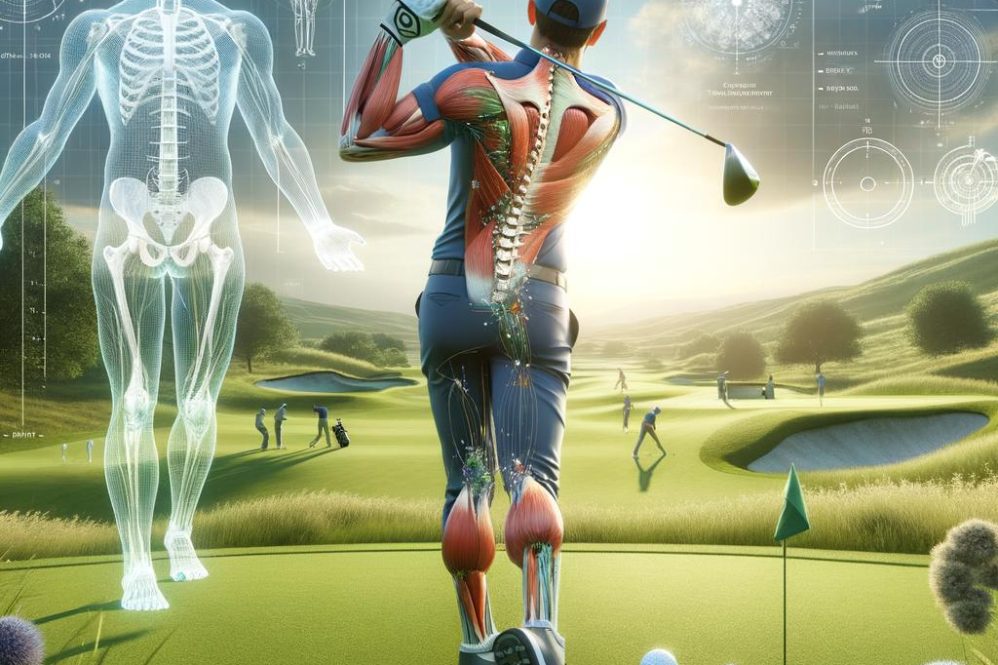

The execution and completion of the golf swing are governed by measurable mechanical principles that mediate movement efficiency, accuracy, and injury risk. Framing the follow-through as an integral phase of the swing-rather than a merely aesthetic afterthought-permits targeted analysis of segmental kinematics, intermuscular coordination, and sensorimotor feedback that together determine clubface orientation and ball flight. Drawing on the interdisciplinary discipline that applies mechanics to biological systems,this examination situates follow-through mechanics within a broader biomechanical context to clarify how forces,torques,and neural control interact to produce repeatable performance.Attention is focused on three interrelated domains: kinematic sequencing (timing and magnitudes of joint rotations and segment velocities), kinetic contributors (ground reaction forces, joint moments, and energy transfer through proximal-to-distal segments), and neuromuscular control (activation patterns, eccentric-concentric transitions, and proprioceptive/visual feedback loops). Integrating empirical assessment methods and practical training implications, the subsequent analysis links theoretical principles to coaching cues and measurement strategies intended to enhance shot precision, promote consistency across conditions, and reduce mechanical sources of injury.

Kinetic Chain Integration and Energy Transfer During the Follow-Through: Principles and Coaching Recommendations

In skilled striking, the follow-through is the visible expression of a coordinated kinetic chain that began with ground contact. Effective energy transfer follows a proximal-to-distal sequence: the lower limb generates ground reaction forces that are transmitted through pelvic rotation,thoracic counter-rotation,shoulder girdle orientation,and finally through the lead arm and wrist to the club. this sequential timing minimizes intersegmental energy loss and reduces compensatory moments at distal joints.Segmental coupling-the mechanical linkage between adjacent body segments-must be maintained through appropriate stiffness modulation and timely muscle activation to preserve momentum and directional control during the follow-through.

Energy moderation during the exit phase is as critical as its generation. While peak power frequently enough occurs just prior to impact, the follow-through governs how residual angular momentum is dissipated or redirected, influencing shot dispersion and repeatability. Musculotendinous eccentric control decelerates the distal segments while allowing proximal segments to continue a controlled rotation, thereby reducing unwanted torque transfer to the wrists and hands. The following compact reference clarifies primary roles for each major segment during the follow-through:

| Segment | Primary function in follow-through |

|---|---|

| Pelvis | Sustain rotational momentum; transmit GRF |

| Thorax | Coordinate dissipation; stabilize line of force |

| Lead arm & wrist | Control lever release; fine-tune clubface orientation |

Neuromuscular control underpins reliable kinetic chain integration. effective follow-through requires feedforward motor planning that times muscle activations to anticipated contact forces, plus rapid feedback corrections informed by proprioception and vestibular input. Coaching should thus include drills that enhance temporal sequencing and eccentric strength:

- Rhythmic med ball throws to reinforce torso-hip sequencing.

- Slow-motion impact-to-follow-through swings emphasizing controlled deceleration of the wrists.

- Single-leg balance with resisted rotation to improve GRF transmission fidelity.

Thes exercises develop both the timing and the passive-active stiffness relationships necessary for consistent energy transfer.

From a practical coaching perspective, adopt a progression that moves from constraint-led exploratory practice to targeted corrective interventions. Use external focus cues (e.g., “let the hips lead the finish”) and objective biofeedback when available (force-plate data, high-speed video) to quantify improvements. Common faults and succinct corrective strategies include:

- Early wrist release – cue increased thorax rotation and add eccentric wrist-lengthening drills.

- Stalled pelvis – implement resisted band rotations and step-through swings to reestablish proximal drive.

- Excessive head movement – employ head-stability holds and tempo constraints to protect sequencing.

Emphasize measurable progression (tempo, ground force symmetry, and release timing) and integrate recovery loads to preserve neuromuscular efficiency across training cycles.

Angular Momentum, Torque, and Clubhead Deceleration: Biomechanical Determinants of Accuracy

Within the kinematic chain of a full swing, the interplay between rotational inertia and segmental angular velocity determines how kinetic energy is transmitted to the club. Conservation of angular momentum about the spine axis means that incremental increases in trunk rotation velocity must be balanced by coordinated changes in the moment of inertia of the proximal segments; otherwise, unwanted lateral forces appear at the clubhead. Quantitatively,small variations in segment orientation during the follow-through can translate into measurable lateral deviations at impact,so precise control of rotational timing is essential for predictable launch direction.

The generation and modulation of torque by the hips, trunk, and lead arm are central to both maximizing speed and stabilizing the clubface through impact. Key contributors include:

- Ground reaction torques (foot-to-ground coupling that initiates hip rotation)

- Pelvis-thorax separation (creates a torque differential that accelerates the shoulders)

- Forearm and wrist moments (fine-tune clubface orientation during release)

Deceleration of the clubhead during and after impact is not merely a loss of speed but a determinant of spin axis and dispersion. Rapid, unplanned deceleration – often from early wrist collapse or abrupt grip tension – increases sidespin and vertical spin variability, degrading accuracy. The table below summarizes representative biomechanical relationships observed in follow-through analyses:

| Variable | Typical Effect on Accuracy |

|---|---|

| Trunk angular velocity | Higher values → improved distance; requires timing control for direction |

| Late wrist pronation | Reduces sidespin when timed with impact |

| clubhead deceleration | Excessive deceleration → increased dispersion |

From an applied perspective, interventions should emphasize coordinated torque sequencing and controlled release rather than maximal force production alone. Training priorities include targeted mobility to allow safe trunk rotation, neuromuscular drills that habituate consistent torque timing, and feedback-driven exercises (IMU or motion-capture cues) to detect premature deceleration. Monitoring metrics such as peak angular velocity, time-to-peak torque, and post-impact deceleration magnitude provides actionable data to refine follow-through mechanics and enhance shot accuracy.

Lower Limb and Pelvic Mechanics for Stabilization and Directional control: Techniques to Reduce Variability

Effective stabilization and directional control during the follow-through depend fundamentally on coordinated force transfer through the lower limbs and pelvis.Ground reaction forces must be directed and modulated via controlled ankle, knee and hip joint stiffness to preserve a stable base while allowing transverse rotation of the pelvis.Maintaining an appropriate stance width and foot orientation optimizes the base of support and minimizes excessive mediolateral center-of-pressure excursions that correlate with shot dispersion. In practice, emphasize steady weight transfer rather than fixed foot positions: this reduces compensatory upper-body kinematic variability and preserves momentum continuity through impact.

Temporal sequencing of joint actions is critical: early activation of the lead-side lower limb prepares a platform for pelvic rotation, while controlled eccentric lengthening of the trail-side hip extensors permits energy transfer without loss of balance.Pelvic rotation should be governed by coordinated transverse plane torque rather than excessive lateral translation; this preserves shot direction by aligning the pelvis-thorax coupling through the follow-through. Training should therefore prioritize dynamic pelvis-on-femur control and decoupling of unwanted frontal-plane motion from desired transverse rotation.

Neuromuscular strategies that reduce movement variability include anticipatory postural adjustments,refined proprioceptive feedback,and task-specific co-contraction patterns. The following simple drills are effective for stabilizing pelvic mechanics and lowering variance in kinematic outcomes:

- Single-leg holds: improves unilateral stance stability and proprioception.

- Resisted hip rotation: trains pelvic control against perturbing torques.

- Segmented tempo swings: enforces predictable sequencing and reduces compensatory motion.

| Drill | Primary outcome |

|---|---|

| Single-leg hold (30s) | Stance stability |

| Resisted hip rotation (bands) | Pelvic control |

| Perturbation taps (coach) | Reactive balance |

Implementation should follow a progressive framework combining quantitative feedback and constrained practice to reduce unwanted variability. Monitor simple metrics-standard deviation of pelvis rotation angle, mediolateral COP path length, and stepwise changes in stance width-and use video or inertial sensors for immediate feedback. Coaching cues should be concise and biomechanically grounded (for example: “anchor through the lead foot,” “rotate on a stable pelvis”) and paired with targeted drills; together these interventions produce measurable reductions in kinematic variance and improved directional repeatability of the follow-through.

Thoracic Rotation and Shoulder Sequencing: Strategies to Maintain Consistent Clubface Alignment

Thoracic mobility is a primary determinant of a reproducible rotational platform for the shoulders and therefore a critical factor in maintaining consistent clubface alignment.The thoracic region-by definition, the segment of the spine associated with the thorax and encasing the thoracic cavity that contains the heart and lungs-provides the axial rotation that decouples upper-body turn from pelvic motion. When thoracic rotation is adequate and symmetrical,the shoulders can rotate on a stable ribcage axis,reducing compensatory wrist or forearm adjustments that commonly alter face angle at impact.

The shoulder complex must sequence relative to thoracic rotation in a controlled proximal‑to‑distal cascade: trunk rotation initiates, the scapula and clavicle continue the transfer, and the humerus then follows to present the clubface. Emphasize the integration of scapulothoracic rhythm and timed glenohumeral external rotation to avoid early release or late closing of the face. At an academic level, reliable alignment arises from consistent timing rather than maximal range alone-an optimal combination of mobility, motor control, and stiffness regulation.

- Mobility drills: thoracic rotations on foam roller, seated twist with band dissociation.

- Stability drills: scapular retraction holds,closed‑chain shoulder presses to train positional control.

- Sequencing drills: slow‑motion half swings with a pause at transition; exaggerated lead‑side rotation to reinforce timing.

- Monitoring cues: mirror checks for shoulder plane, use of impact tape or alignment rod to verify face consistency.

Key kinematic cues can be summarized to guide coaching and practice. The simple table below (WordPress table styling) provides immediate, actionable associations between phase, primary rotational action, and concise coaching cues that help preserve clubface alignment through the follow‑through.

| Phase | primary rotation | Coaching cue |

|---|---|---|

| Transition | Thorax initiates turn | Lead ribcage rotates first |

| Downswing | Pelvis leads, thorax follows | Delay shoulder clearance slightly |

| Impact | Scapula stabilizes, humerus presents | Maintain scapular tension |

| Follow‑through | Controlled deceleration of shoulder complex | Allow full thoracic rotation without collapsing |

From an injury‑prevention and training prescription perspective, progressive loading of thoracic rotational capacity combined with scapular endurance work reduces harmful compensation patterns that threaten shoulder and cervical structures. Use measurable benchmarks (e.g., degrees of thoracic rotation, timed isometric scapular holds) and implement periodized practice blocks: mobility, then control under slow loads, then high‑speed integration. Reinforcing the correct shoulder sequencing via deliberate feedback-video,tactile guidance,or immediate biofeedback-will systematically improve face consistency without sacrificing swing economy.

Wrist and Forearm Kinematics in release Timing: minimizing dispersion Through Controlled Forearm Mechanics

Precision in the distal kinematic chain depends on the complex articulation of the wrist and the rotational capacity of the forearm. The wrist is not a simple hinge but a multi-bone carpal complex that transmits and modulates forces from the forearm to the clubface; this anatomical structure inherently constrains and enables fine-tuned release behaviors.Neuro-muscular coordination between wrist flexors/extensors and the forearm pronator-supinator system governs the timing of angular transfer at the instant of ball release. From a biomechanical perspective, small changes in wrist orientation or forearm rotation at impact produce magnified changes in face angle and ball spin, so **precise control of wrist posture and controlled pronation timing** are critical to reduce lateral and distance dispersion.

Quantitatively, three kinematic variables most strongly predict dispersion when analyzed in conjunction with proximal sequencing: **forearm pronation rate**, **wrist flexion/extension angle at impact**, and **release angular velocity** of the lead wrist. Secondary descriptors-such as radial/ulnar deviation and relative lag (the angle between the clubshaft and forearm prior to release)-add explanatory power for face orientation variability.Coaches and researchers should monitor these metrics concurrently with trunk rotation and arm extension to capture coupling effects. Typical measurable markers include:

- Forearm pronation velocity (deg·s⁻¹)

- Wrist flexion angle at impact (deg)

- Time-to-release relative to peak trunk rotation (ms)

- Clubhead rotational acceleration promptly post-impact (deg·s⁻²)

Collectively these variables form a concise kinematic fingerprint for diagnosing release-related dispersion.

Practical interventions that isolate distal control while preserving proximal sequencing are effective for training controlled release. The table below summarizes concise drills, their primary mechanical target, and the expected outcome when performed with deliberate feedback. Use of light resistance,tempo constraints,and impact-feedback tools accelerates motor learning by exaggerating the sensory consequences of premature or excessive pronation.

| Drill | Primary target | Expected Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| Towel-Lag Drill | Maintain wrist lag | Delayed release, reduced slice |

| Impact-Bag Contact | Stabilize wrist angle at impact | Consistent face orientation |

| Pronation-Timing Swing | Sync pronation with follow-through | Lower dispersion, improved carry |

When minimizing shot dispersion, individual variability in forearm morphology and neuromuscular strategy must guide prescription. Objective feedback-high-speed video, inertial measurement units at the forearm and club, and force-plate derived temporal markers-enables evidence-based tailoring of drills and loading progressions. Emphasize progressive constraints: first restore repeatable wrist posture, then refine pronation timing under increasing clubhead speed. In practice, **prioritize reproducible impact wrist angle over maximal late release speed**, as controlled release with consistent geometry typically yields superior accuracy across skill levels.

Ground Reaction Forces, Weight Transfer, and Balance: Quantifying and Training for optimal Directional Intent

Ground reaction forces (GRFs) are the mechanical link between the golfer and the clubhead: they represent the external forces transmitted through the feet into the ground and are central to producing and directing rotational and translational impulse during the swing. From a biomechanical perspective-where movement and force are analyzed to explain performance and injury risk-GRFs are resolved into vertical, mediolateral and anteroposterior components that together determine the resultant vector of support and propulsion. Quantifying the timing and magnitude of these vectors (for example,peak vertical GRF,lateral shear at impact,and the rate of force growth) reveals how effectively a player converts ground interaction into clubhead velocity and directional intent. Using synchronized kinematics and force-data allows precise identification of whether inefficiencies arise from insufficient force production, mistimed transfer, or poor alignment of the resultant GRF vector relative to the target line.

Measuring the dynamics of weight transfer and balance requires objective tools: force plates, pressure-mapping insoles, and center‑of‑pressure (COP) tracing provide the primary data streams used in applied research and coaching. Key variables include COP displacement path, time-to-peak force on the lead limb, inter-limb force asymmetry, and impulse across the downswing-to-follow-through interval. The following table summarizes select metrics, how they are commonly measured, and succinct training targets that reflect functional directional control rather than normative absolutes.

| Metric | Method | Representative Target |

|---|---|---|

| Peak vGRF (lead) | Force plate | > 1.0 × body mass at/just after impact |

| COP lateral shift | Pressure mat | Progressive medial displacement toward lead foot |

| Timing of peak force | Force-time curve | Peak within 50-120 ms of impact |

Training interventions should be engineered to manipulate both magnitude and direction of GRFs while preserving dynamic balance. Effective drills emphasize sequencing, stiffness modulation, and proprioceptive refinement. Practical,evidence‑led examples include:

- Step‑through med ball throws: promotes coordinated weight transfer and rotational impulse with measurable horizontal GRF.

- Single‑leg balance swings: increases COP control and trains the ability to generate force from a stable base.

- Lateral plyometric hops: develop rapid mediolateral force production and improve rate of force development for directional adjustments.

- Resisted swing paths: using bands or sleds to alter the required GRF vector and reinforce desired sequencing.

Each intervention should be progressed by increasing load,speed,or perturbation complexity and monitored for compensatory trunk or knee mechanics.

Coaching translation requires objective feedback and phased progression: baseline assessment, targeted training blocks, and re-assessment with the same instrumentation to quantify change. Use real‑time biofeedback (force plate displays,pressure heatmaps) to provide immediate cues like “shift pressure toward the lead heel” or “increase lateral impulse early in the downswing.” Progression criteria should combine performance (e.g., consistent COP trajectory and increased lead vGRF) with stability (reduced post‑shot sway and preserved trunk control). In applied settings, the goal is not maximal ground force per se but the reproducible alignment of the resultant GRF vector with the intended line of play, achieved through iterative measurement, targeted drills, and objective thresholds that define both directional intent and lasting balance.

Assessment Protocols and evidence-Based Drills to Enhance Follow-Through biomechanics and Precision

Assessment design should follow contemporary principles of standardized testing to ensure that conclusions about follow-through mechanics are both reliable and valid. Drawing on guidelines from formal testing literature (e.g., APA testing and assessment frameworks), recommended components include a standardized warm-up, scripted instructions, and consistent environmental conditions (same club, tee height, and target surroundings). Instrumentation should combine kinematic and kinetic systems for convergent measurement: 3D motion capture or high-fidelity IMUs for segment angles and angular velocities,force plates for ground reaction profiles,and a launch monitor for ball-flight and clubface data. These layered measures increase construct validity by triangulating the biomechanical determinants of an effective follow-through.

Protocol parameters must be specified a priori to reduce measurement error and facilitate longitudinal comparison. Typical recommendations: collect a minimum of 8-12 full-swing trials per condition after a 10-minute warm-up, randomize trial order if testing multiple interventions, and allow standardized rest intervals to mitigate fatigue. Core outcome metrics should include: clubface angle at impact, clubhead path, pelvic-to-shoulder separation at impact, peak angular velocity of the lead arm, and lateral dispersion (radial error) of landing location. Where possible, compute and report psychometric indices (e.g., ICC for test-retest reliability, SEM for measurement precision) so that observed changes can be interpreted against measurement noise.

Evidence-informed drills focus on reinforcing desirable follow-through kinematics while preserving shot precision. Recommended drills (perform 2-3 sets of 8-12 reps, progressing by load or tempo):

- Pause-and-Release Drill: Pause at the intended impact position for 1-2 seconds to ingrain correct wrist and arm alignment, then release through a controlled follow-through to train timing.

- Mirror-Feedback with Alignment Markers: Use a mirror or video feedback with taped reference lines to correct shoulder-pelvis dissociation and ensure a full finish posture oriented toward the target.

- Metronome Tempo Progression: Use a metronome to stabilize backswing-to-follow-through ratio; research on tempo control shows improved repeatability when temporal cues are imposed.

- weighted-club sequence: Progress from light to standard to slightly heavy clubs to reinforce muscle activation patterns that support consistent extension and deceleration in the follow-through.

Progress monitoring should combine objective thresholds and individualized baselines to guide training decisions. Use statistical process control logic: flag changes that exceed the SEM or fall outside a 95% confidence interval of the baseline mean; compute ICCs periodically to confirm maintained reliability. The simple reference table below summarizes practical metrics and suggested acceptability targets for applied use in coaching environments.

| Metric | Instrument | Practical Target |

|---|---|---|

| Clubface angle at impact | Launch monitor / high-speed video | ±2° of target |

| Radial dispersion | Rangefinder/launch monitor | ≤10 yd SD (short game adjusted) |

| Pelvic rotation at impact | IMU / motion capture | 30°-45° (individualized) |

| Ground reaction stabilization | Force plate | Consistent medial-lateral impulse |

Integrate these data into periodized practice plans: prioritize drill work that corrects the largest standardized deficits, re-assess at predetermined checkpoints, and combine objective feedback with qualitative coach observation to maximize transfer to on-course performance.

Q&A

Q1. What is meant by the “follow-through” in a golf swing, and why is it significant from a biomechanical perspective?

Answer: The follow-through is the phase of the golf swing that immediately follows ball impact and comprises the motion through which the body and club decelerate and re-establish balance. Biomechanically, it is not merely stylistic but reflects the quality of the kinematic sequence, force transfer, and energy dissipation generated earlier in the swing. A technically sound follow-through indicates effective proximal-to-distal sequencing, appropriate joint loading and deceleration strategies, and preservation of postural control-factors that influence precision, repeatability, ball flight, and injury risk.

Q2. What kinematic sequence underpins an effective follow-through?

answer: Effective follow-through results from the proximal-to-distal kinematic sequence: initiation and acceleration begin with the lower body (ground reaction force generation and hip rotation), propagate through the pelvis and trunk (torso rotation and X-factor), continue through the shoulders and arms (shoulder rotation and forearm motion), and culminate at the hands and clubhead (wrist release and club rotation). Proper sequencing ensures maximal efficient energy transfer to the ball while facilitating controlled deceleration after impact.

Q3. How do ground reaction forces (GRFs) and weight transfer influence follow-through mechanics?

Answer: GRFs and weight transfer provide the primary external impulses that drive pelvis rotation and trunk acceleration. A coordinated lateral-to-medial and vertical GRF profile during downswing produces effective momentum and establishes the stance for impact. post-impact,the lower limb must absorb and redirect forces to stabilize the body,enabling a balanced follow-through. Insufficient or poorly timed GRFs can disrupt sequencing, causing compensatory motions that degrade precision.

Q4. What role do pelvis and thorax rotations play in achieving a precise follow-through?

Answer: Pelvis rotation initiates energy transfer and establishes separation (X-factor) between pelvis and thorax, which amplifies stored elastic energy and angular velocity. Thorax rotation follows, converting that stored energy into clubhead speed. For the follow-through, the coordinated deceleration of these segments ensures the club path is maintained and the body remains balanced. Excessive or prematurely arrested rotations can alter impact geometry and lead to mis-hits or loss of control.Q5. Which muscles and activation patterns are critical during follow-through?

Answer: Key muscles include the hip extensors and rotators (gluteus maximus/medius, adductors), trunk rotators and stabilizers (obliques, erector spinae, multifidus), scapular stabilizers and shoulder rotators (rotator cuff, trapezius), and forearm musculature for wrist control. EMG studies of similar rotational tasks indicate an alternation of concentric activation during acceleration and eccentric control during deceleration; effective follow-through requires timely eccentric activity to dissipate energy safely while preserving kinematic sequence integrity.

Q6. How does wrist and hand mechanics affect follow-through and shot precision?

Answer: Wrist hinge, release timing, and forearm rotation determine clubface orientation and clubhead speed at and after impact. A controlled release allows optimal loft and face angle consistency, whereas an early or abrupt release (cast) or late, forced flick can disrupt path and face alignment, increasing dispersion. During follow-through,the hands should continue along a trajectory consistent with the intended club path while decelerating under eccentric control to avoid abrupt deviations.

Q7. What are frequent biomechanical faults observable in poor follow-throughs, and what causes them?

Answer: Common faults include:

– Early release (loss of lag): often due to inadequate proximal sequencing or compensatory arm-driven swing.

– reverse pivot or weight shift errors: caused by mistimed GRFs and poor balance.

– Over-rotation or “sway”: from excessive lateral motion or loss of lower-limb stability.

– Restricted follow-through (short finish): indicates premature deceleration or insufficient trunk rotation.

Each fault typically reflects upstream deficiencies in force production, timing, or neuromuscular control rather than being an isolated problem.

Q8. How does balance and center-of-mass control contribute to a consistent follow-through?

answer: Stable control of the center of mass (CoM) relative to the base of support allows efficient force transfer and maintains club-path geometry through impact and follow-through. Effective postural adjustments-mediated by lower-limb joints and trunk musculature-permit controlled deceleration and final alignment. Instability or excessive CoM excursions increase movement variability and reduce shot repeatability.

Q9.What objective methods can be used to assess follow-through biomechanics?

answer: Assessment tools include 3D motion capture (kinematics), force plates (GRFs and center-of-pressure), surface EMG (muscle activation timing and amplitude), inertial measurement units (IMUs) for field-based kinematics, high-speed video for qualitative/quantitative analysis, and ball-tracking systems (ball speed, launch angle, spin). Combined multimodal assessment yields the most informative profile of kinematic sequencing, loading patterns, and outcome measures.

Q10.Which training interventions and drills reliably improve follow-through mechanics?

Answer: Evidence-informed interventions emphasize restoring proper sequencing, force production, and neuromuscular control. Examples:

– Proximal-to-distal drills (pelvis-first rotation exercises).- Medicine-ball rotational throws to reinforce trunk-to-arm energy transfer and follow-through trajectories.

– Impact-to-follow-through drills that focus on extension and balanced finishes.

– Resistance- or velocity-specific training (weighted clubs, overspeed drills) for power, combined with technique monitoring to preserve mechanics.

– Video or IMU-based augmented feedback to accelerate motor learning. Progressive overload, specificity, and motor learning principles should guide drill prescription.

Q11. How do feedback mechanisms and motor learning principles support follow-through mastery?

Answer: Motor learning relies on intrinsic feedback (proprioception, vestibular input) and augmented feedback (video, coaching cues, biofeedback). early learners benefit from external focus cues (e.g., “finish with the chest facing the target”) and immediate visual or quantitative feedback to reduce error and shape the kinematic sequence. Schedule feedback to foster self-assessment and retention (faded or summary feedback) and incorporate variable practice to enhance adaptability and robustness of the follow-through under varying conditions.

Q12. What are the primary injury considerations associated with faulty follow-through mechanics?

Answer: Faulty follow-throughs can increase repetitive loading and peak stresses on the lumbar spine (due to excessive axial rotation and shear), shoulders (excessive eccentric loading of rotator cuff and scapular stabilizers), and elbows (valgus/varus stresses with poor release mechanics).Prevention strategies include screening for mobility and strength deficits, corrective conditioning (eccentric trunk control, scapular stabilization, hip strength), ensuring appropriate swing kinematics, and graded load progression in training.

Q13. In what ways does follow-through quality transfer to performance metrics such as accuracy and consistency?

Answer: A mechanically consistent follow-through is a proxy for proper impact mechanics and sequencing, which influence clubface angle, path, and clubhead speed-primary determinants of launch conditions (direction, spin, speed). Consequently, improved follow-through correlates with reduced shot dispersion (improved precision) and repeatable ball flight, provided that the pre-impact mechanics are maintained. Transfer is mediated by the degree to which follow-through reflects stable, repeatable movement patterns rather than compensations.

Q14. What limitations and individual differences should practitioners consider when applying biomechanical principles?

Answer: Inter-individual variability in anatomy, mobility, strength, injury history, and motor preferences means there is no single “ideal” cosmetic finish. Practitioners must distinguish between functional variability that preserves performance and maladaptive patterns that increase injury risk or reduce precision. Measurement constraints (lab vs. field), ecological validity of drills, and the athleteS stage of learning also moderate intervention efficacy. Assessment-driven, individualized programs that prioritize function and performance outcomes are recommended.

Q15.What are priority research directions to better understand and optimize follow-through biomechanics?

answer: Priority areas include longitudinal intervention trials linking specific biomechanical training to on-course performance and injury outcomes; development of portable multimodal monitoring (IMU + force estimation + muscle activation) for ecological assessment; refined models of segmental energy transfer accounting for soft-tissue dynamics; and machine-learning approaches to identify individualized optimal movement solutions. Greater integration of motor learning theory with biomechanical measurement will also advance practical coaching strategies.

Practical summary for coaches and researchers:

– Emphasize proximal-to-distal sequencing and timely GRF request rather than aesthetic finish positions.

– Use objective assessment (video,IMUs,force measurements) to identify whether follow-through faults originate from force production,timing,or control issues.- Apply drills that reinforce trunk-to-arm energy transfer and eccentric deceleration, combined with progressive conditioning to mitigate injury risk.

– Individualize interventions, monitor outcomes with both kinematic and performance metrics, and employ motor-learning principles when delivering feedback.

If you would like, I can convert this Q&A into a one-page coach’s checklist, provide sample drills with progressions, or draft assessment protocols using field-amiable sensors.

the follow-through is not merely the aesthetic coda of the golf swing but a critical phase in which kinematic sequencing, intermuscular coordination, and sensorimotor feedback converge to determine precision and repeatability. Grounded in the principles of biomechanics-the application of mechanical and physical laws to human movement-an effective follow-through reflects optimized energy transfer, controlled deceleration, and stable alignment of the body-club system. Attention to trunk-pelvis dissociation, timed lower‑body sequencing, distal-to-proximal velocity transitions, and eccentric control during deceleration can therefore materially improve shot dispersion and reduce injury risk.

For practitioners and researchers, these insights recommend a dual pathway: evidence-informed coaching that integrates objective movement analysis (e.g., three-dimensional kinematics, force-plate and EMG data) with individualized training interventions that address strength, mobility, and neuromuscular timing; and continued empirical inquiry into how variability, fatigue, and task constraints modulate follow‑through mechanics. Such an approach aligns with broader biomechanical scholarship that emphasizes the mechanistic study of movement to enhance performance and safety.

Ultimately, mastery of the follow-through demands both conceptual understanding and practical application: coaches and athletes who translate biomechanical principles into targeted assessment, cueing, and conditioning are best positioned to achieve greater precision, consistency, and longevity in performance.

Biomechanical Principles for Mastering Golf Follow-Through

Why the Golf Follow-Through Really Matters

The golf follow-through is far more than a stylistic finish – it is the visible result of how your body generated and delivered speed, controlled the clubface, and managed momentum through impact. Biomechanics, the study of forces and motion applied to living systems, explains how ground reaction forces, torque, and sequential rotation create efficient, repeatable follow-through mechanics that improve shot accuracy, distance and consistency (see a basic definition of biomechanics here).

Key Biomechanical Principles for a Reliable Follow-Through

1. Kinetic Chain & Sequential Activation

The golf swing depends on a well-timed kinetic chain: legs → hips → torso → shoulders → arms → hands/club. Efficient sequencing transfers energy from the ground up into the clubhead so the follow-through continues that transfer rather than abruptly stopping it. A correct sequence produces a smooth, high-velocity finish and proper clubface control.

2. Ground Reaction Force & weight Transfer

Pushing off the trail leg into the lead side creates ground reaction forces that drive hip rotation and accelerate the torso through impact. A complete follow-through typically shows a clear weight shift to the lead foot and an athletic finish wiht the trail foot up on the toe. consistent weight transfer stabilizes the swing plane and reduces compensatory movements.

3. Angular Momentum, Torque & Hip Drive

Rotation of the pelvis ahead of the shoulders (hip lead) creates torque – the stored rotational energy that helps accelerate the torso and arms. This torque should be released sequentially rather than all at once. The follow-through reflects how well torque was used: a balanced finish with the chest rotated toward the target indicates effective torque application.

4. Center of Mass & Posture Control

Maintaining a stable center of mass during impact prevents swaying, hanging back, or reverse pivot. The follow-through should be a controlled continuation of the body’s center of mass moving naturally toward the target. Proper posture (spine angle and head position) allows rotation without lateral collapse.

5. Release Timing & Deceleration

The wrists and forearms decelerate after impact to control clubface rotation. A “late,controlled release” (not an early flip or cast) preserves clubhead speed while ensuring the face is square through impact and into the follow-through. The finish indicates if you released too early (flat finish, low hands) or too late (over-rotated or tense finish).

6.Conservation of Angular Momentum & Moment of Inertia

How you distribute mass (arms, club, torso) affects rotational speed; tucking the arms into a compact rotation increases rotational velocity, while extending them changes moment of inertia. A natural, athletic follow-through will show a balance between extension (for path control) and compact rotation (for speed).

How to Read the Follow-Through: What the finish Tells You

- Chest fully rotated toward the target + weight on lead foot = good weight transfer and hip rotation.

- Hands low and early = possible early release or casting.

- Trail foot flat and heavy = insufficient shift to the lead side (hanging back).

- Over-rotated torso with balance loss = tempo or timing issue – often too aggressive downswing.

Practical Tips & Drills to Improve Follow-Through Mechanics

Use thes coaching cues and drills to train follow-through that reflects sound biomechanical principles.

Coaching Cues (quick, player-facing)

- “Lead with your hips, feel your chest follow.”

- “Finish with weight on your left big toe” (for right-handed golfers).

- “Keep the spine angle through impact, rotate around it.”

- “Delay the release – let the body pass the hands.”

Core Drills

- Step-Through Drill: Start with feet together, make a slow swing, then step the lead foot toward the target during the follow-through to force weight transfer and hip rotation.

- Toe-Rise Drill: Practice finishing with the trail foot on the toe – exaggerate the step to feel the weight on the lead side.

- Towel Under Arm: Place a small towel under the trail armpit and keep it there through impact and into the follow-through to promote connected rotation and prevent arm separation.

- Impact Bag or Pad: Punch into an impact bag to feel the forward momentum and extension through the ball, then allow your body to rotate into a balanced finish.

- Slow-Motion Reps: Slow swings at 25-50% speed focusing on sequencing and a full balanced finish – build motor patterns before increasing speed.

Simple WordPress Table: Principles, Coaching Cue & Drill

| Biomechanical Principle | Coaching Cue | Practice Drill |

|---|---|---|

| Kinetic Chain | “Lead with your hips” | Step-Through Drill |

| Weight Transfer | “Finish on lead toe” | Toe-Rise Drill |

| Release Timing | “Let the body pass the hands” | Towel Under Arm |

Common Follow-Through Faults and Biomechanical Fixes

- Hanging Back – symptoms: heavy trail foot, low ball contact. Fix: step-through and toe-rise drills to force weight transfer; focus on initiating downswing with the lower body.

- Early Release (Casting) – symptoms: flat finish, loss of distance. Fix: strengthen wrist and forearm control drills; use impact bag and delay release cues.

- Over-rotation or Loss of Balance – symptoms: stumble or fall after finish. Fix: tempo work (metronome drills), and maintain posture – rotate around the spine angle.

- Reverse Pivot – symptoms: too much weight forward on backswing, inhibited follow-through. Fix: foot-pressure drills and slow-sequence swings to restore proper weight shift.

Measurement, Feedback & Training Tools

Improve follow-through using objective feedback:

- Slow-motion video: Record swings from down-the-line and face-on perspectives to analyze finish position and sequencing.

- Launch monitor metrics: Clubhead speed, smash factor, spin and attack angle all reflect how your follow-through and impact were managed.

- Wearables & Sensors: Inertial sensors provide tempo, hip-shoulder separation and rotational velocity data.

- Force plates (advanced): Reveal ground reaction force patterns and weight transfer timing through the swing.

Sample 4-Week Follow-Through Practice Plan

| Week | Focus | Drills (15-20 min/session) |

|---|---|---|

| Week 1 | Sequencing & weight transfer | Slow swings + Step-through Drill |

| Week 2 | Release timing | Towel Under Arm + Impact Bag |

| Week 3 | Tempo & balance | Metronome swings + Toe-Rise Drill |

| Week 4 | Integration & on-course | Range sessions + video feedback |

case Study: How a mid-Handicap Golfer Improved Finish & accuracy

Context: A 15-handicap golfer struggled with blocks and low-launch irons because they were hanging back through impact and releasing early.

Intervention:

- Week 1: Introduced step-through and slow-motion sequencing to train lower-body initiation.

- week 2: Used towel-under-arm and impact bag to develop a connected release and forward extension through impact.

- Week 3: implemented metronome tempo sessions and video analysis to refine timing and balance.

- Week 4: Integrated changes on the course with 9-hole practice rounds focusing on finish position.

Outcome: Within four weeks the golfer reported more consistent ball striking, improved ball flight (reduced block), and better dispersion. Video showed a cleaner weight shift onto the lead foot and a balanced, rotated finish – strong indicators of improved biomechanical sequencing.

Practical Notes for Coaches and players

- Train slowly before adding speed. Motor learning favors accurate patterns at low speed first.

- Use simple cues. players respond best to 1-2 clear cues rather than a laundry list.

- Connect fitness to mechanics. Hip mobility, core stability and ankle control directly impact follow-through quality.

- Monitor fatigue. A deteriorating finish late in practice signals loss of sequencing or posture – stop and reset.

Additional Resources

- Introductory biomechanics overview (for coaches and curious golfers): Biomechanics – Britannica

Apply these biomechanical principles and repeatable drills to your practice plan, and your golf follow-through will become a reliable barometer of improved swing mechanics – increasing accuracy, delivering more consistent ball striking, and helping you shape shots with confidence.