The golf swing represents a highly coordinated, multi-joint motor task in which precise timing, segmental sequencing, adn force production converge to produce repeatable ball-flight outcomes. Its dual demands-maximizing clubhead speed and accuracy while minimizing cumulative musculoskeletal load-make the swing an instructive model for applied biomechanics. Understanding the mechanical and physiological determinants of swing performance is therefore essential for coaches, clinicians, and researchers seeking to optimize technique, enhance performance, and reduce injury risk.

Biomechanics, broadly construed, frames human movement in terms of mechanics applied to biological systems, integrating principles from physics, anatomy, and motor control to characterize how muscles, bones, tendons, and ligaments generate and transmit forces that produce motion. Within the context of the golf swing, this framework encompasses kinematic description of segmental trajectories and timing, kinetic analysis of joint moments and ground reaction forces, and neuromuscular inquiry of activation patterns and coordination strategies. Such multidisciplinary inquiry translates descriptive observation into quantifiable metrics that can guide evidence-based intervention.

This article synthesizes current biomechanical knowledge relevant to golf-swing performance,with attention to methodological approaches (e.g.,motion capture,force platforms,electromyography,and wearable sensors),key kinematic and kinetic signatures associated with effective and efficient swings,and the neuromuscular dynamics that underpin skill acquisition and consistency. Emphasis is placed on how mechanical principles-such as proximal-to-distal sequencing, conservation and transfer of angular momentum, and segmental stiffness modulation-relate to performance outcomes and injury mechanisms commonly observed in golfers.implications for practice are considered through a translational lens: how biomechanical evidence can inform technical refinement, individualized coaching cues, training prescription, and injury-prevention strategies, as well as the limitations of current research and priorities for future investigation. By situating technical instruction within an empirically grounded biomechanical framework, practitioners can better align coaching interventions with the underlying mechanisms that determine swing efficiency, robustness, and safety.

Kinetic and Kinematic Foundations of the Golf Swing: Ground Reaction Forces, Segmental Sequencing and Practical Training Recommendations

Ground reaction forces (GRFs) form the mechanical foundation of the swing, acting as the primary external impulse that the golfer transmits into clubhead velocity. Efficient swings exploit both vertical and horizontal GRF components: vertical force supports postural integrity and allows elastic recoil of the lower back and hips,while horizontal shear and resultant vectors drive rotational momentum. Control of the center of pressure under each foot-timed lateral transfer and subtle pressure redistribution-permits graded request of force rather than abrupt, energy‑wasting impulses. From a biomechanical standpoint, optimizing the direction, magnitude and timing of GRFs reduces compensatory torques at the lumbar spine and improves repeatability of ball contact.

The kinematic architecture of a high‑performance swing is characterized by a consistent proximal‑to‑distal sequencing of segmental angular velocities; in practical terms, the pelvis initiates rotation, the thorax follows with a phase lead that creates separation, then the upper limbs and club accelerate to their peak. This ordered pattern (pelvis → thorax → arms → club) produces an additive velocity cascade that maximizes distal segment speed while minimizing internal work and joint loading. Precise intersegmental timing-measured as phase delays or sequencing intervals-correlates strongly with clubhead speed and with reductions in peak joint moments when compared to non‑sequenced strategies.

Training should progress from motor control to force production and finally to power expression, with drills selected to address sensory feedback, segmental timing and force application. Emphasize exercises that: stabilize foot‑to‑ground interaction, enhance controlled pelvis‑thorax separation, and reinforce rapid but coordinated distal release. Effective drill categories include balance and pressure‑mapping tasks, tempo and pause sequences to ingrain timing, medicine‑ball rotational power for rate of force advancement, and resisted/assisted swings to modulate GRF directionality.Scientific periodization pairs low‑intensity neuromuscular control work early in the cycle with higher‑load, low‑volume power sessions as consistency improves.

Objective assessment is essential for targeted intervention; combine force‑plate measures (peak GRF,center‑of‑pressure path),inertial measurement units (segmental angular velocities and timing),and high‑speed video for kinematic sequencing. Key monitoring metrics are rate‑of‑force‑development, pelvis‑thorax peak delay, and clubhead peak velocity. The table below gives a concise training prescription example linking common drills to measurable targets and recommended frequency to bridge laboratory findings with field practice.

- Measurement tools: force plate, IMU, high‑speed camera

- Primary targets: reproducible GRF vectors, proximal‑to‑distal timing, increased RFD

- Programming principle: control → strength → power

| Drill | Primary Metric | Frequency |

|---|---|---|

| Single‑leg balance w/ pressure feedback | COP stability / balance time | 2×/week |

| Medicine‑ball rotational throw | Peak thorax angular velocity | 2×/week |

| Tempo/pause swings (pauses at top) | Sequencing consistency | 3×/week |

| Step‑through power swings (light resistance) | Peak GRF / RFD | 2×/week |

Role of the Hips and Core in Power Generation: Assessment Protocols and Targeted Conditioning Strategies

Effective transmission of force in the golf swing depends on coordinated action between the hip complex and the trunk. Anatomically, the hip is a **ball-and-socket joint** optimized for weight-bearing and controlled rotation, which makes it uniquely suited to generate transverse-plane torque while supporting axial loads. In the swing, rapid hip extension and transverse rotation generate ground-reaction forces that are transmitted through a relatively stiff, neutral spine; the resulting intersegmental **separation** (pelvis rotating relative to the shoulders) creates stored elastic energy and increases clubhead speed at impact. Consequently, interventions that optimize hip torque generation and maintain spinal integrity produce measurable gains in both distance and consistency.

objective evaluation is essential to identify whether deficits are mobility-, strength-, or motor-control-driven. Recommended assessment protocols include:

- Passive and active hip internal/external rotation (goniometric assessment) to quantify available transverse ROM and left-right symmetry.

- Single-leg squat and step-down tests for dynamic hip control and frontal-plane knee tracking.

- Y-Balance or reach tests to assess unilateral stability and reach asymmetries indicative of injury risk or force-transmission deficits.

- Rotational power tests (e.g., seated medicine-ball rotational throw or instrumented club swings) and isometric hip-extension/dynamometry for force capacity.

Clinicians should interpret results relative to the athlete’s baseline and sport-specific demands; pragmatic targets are interlimb symmetry within ~5-10% and functional ROM sufficient to achieve desired trunk-pelvis separation without lumbar compensation.

Conditioning should be task-specific and progressive, emphasizing both capacity to produce torque and the ability to control that torque transfer through the trunk. Key interventions include:

- Activation and motor-control drills: banded glute bridges, clamshells and split-stance hip hinge patterns to restore early firing and pelvic control.

- Maximal and submaximal strength work: barbell/KB Romanian deadlifts, hip thrusts, and single-leg RDLs (3-5 sets of 4-8 reps) to increase hip-extensor force capacity.

- Power and rate-of-force development: rotational medicine-ball throws, explosive step-ups and short accelerations (3-6 reps, 3-5 sets) performed with high intent to increase angular velocity.

- Anti-rotation and anti-flexion core training: pallof presses, cable chops and loaded carries to improve transmission and resist unwanted lumbar motion.

Programming guidance: incorporate 2-3 targeted hip/core sessions weekly during the readiness phase, biasing strength under higher loads and velocity work nearer to competition for transfer to swing speed.

Practical implementation requires ongoing monitoring and simple benchmarks. Use objective repeatable tests (see table) and track percent improvements rather than absolute single-session values to inform progression and de-load decisions. Balance mobility and stability priorities-restore ROM first where restrictive, then build force capacity, and finally emphasize high-velocity skill integration to convert strength into swing power. Employ periodized blocks (accumulation → intensification → realization) and re-assess every 6-8 weeks to quantify adaptation and refine exercise selection.

| Test | Metric | Short-Term Goal |

|---|---|---|

| Seated med‑ball rotational throw | Throw distance / velocity | ↑ 8-15% in 6-8 wk |

| Hip rotation ROM | Degrees & side symmetry | Symmetry within 5-10% |

| Single‑leg squat | Movement quality score | Reduced valgus / improved depth |

Upper Extremity Mechanics and Clubface Control: Torque Management,Wrist Kinematics and Corrective Technique Cues

Effective management of rotational torque through the upper limbs is central to consistent clubface orientation at impact. The kinetic link from torso rotation to the lead arm and hand must be modulated so that angular momentum is transmitted rather than dissipated by excessive wrist collapse or premature hand release. Emphasis should be on controlled energy transfer: the shoulder girdle and humerus create the primary rotational impulse while the forearm and wrist regulate the final degrees of freedom that determine face angle. In biomechanical terms, small variations in distal segment torque produce large changes in face rotation within the last 100-200 ms before impact, so precise timing and stiffness regulation are essential.

wrist kinematics-comprised of flexion/extension, radial/ulnar deviation, and forearm pronation/supination-directly alter dynamic loft and face angle. The lexical root “upper” (commonly defined as higher or proximal segments) is applicable here as control originates proximally but must be realized distally to influence the clubhead. Observationally, a stable lead wrist through the downswing reduces unwanted face rotation, whereas excessive wrist extension or radial deviation increases open-face tendencies. The short table below summarizes typical wrist postures and their characteristic effects on face control (abbreviated for clinical coaching use):

| Wrist Posture | Common Clubface effect | Coaching Priority |

|---|---|---|

| Neutral/Flat | Square to slightly closed | Maintain through impact |

| Extended (cupped) | Open face, higher loft | Limit extension late |

| Flexed (bowed) | Closed face, lower loft | Prevent early bowing |

practical corrective cues and drills should be concise, externally focused, and grounded in measurable kinematics. Useful cues include: “maintain wrist triangle” to preserve the lead wrist angle through transition; “turn the chest, not just the arms” to reduce premature hand action; and “feel resistance in the lead wrist” to cultivate appropriate stiffness. Recommended drills (brief):

- Impact-bag drill – trains a stable, square face at contact with minimal arm collapse.

- One-arm slow swings (lead arm only) – isolates distal control and wrist proprioception.

- Weighted shaft practice – increases awareness of torque and timing without full speed mechanics.

For applied assessment and progressive training, integrate objective measurement (high-speed video, inertial sensors, and clubface-tracking) with targeted cueing and load manipulation. track metrics such as wrist angle at transition, rate of forearm pronation, and face rotation in degrees/second to quantify improvement. Periodize interventions: initial phase emphasizes proprioceptive stability, mid-phase restores speed under controlled torque, and final phase re-integrates full-body sequencing while monitoring for compensatory upper-extremity patterns. This evidence-informed progression preserves performance gains while reducing the risk of technique-driven inconsistency.

Temporal Coordination and Motor Control: Timing Metrics, Neuromuscular Drills and Progressions to Improve Sequencing

Temporal precision underlies effective energy transfer in the golf swing: the relative timing of pelvis rotation, thorax rotation, and distal clubhead acceleration dictates kinetic chain efficiency and shot outcome. Quantitative timing metrics commonly used in research and applied practice include time-to-peak angular velocity for pelvis and thorax, intersegmental phase lag (pelvis→thorax→arms), and the duration of the downswing interval. These metrics are derivable from high-speed motion capture, wearable IMUs, and synchronized force-plate data; when interpreted collectively they reveal whether inefficiency arises from delayed proximal initiation, premature arm release, or inadequate trunk-hip separation.

Rehabilitation and performance interventions emphasize neuromuscular re-education to restore or refine sequencing. Evidence-informed drills-implemented with graded complexity-target motor planning, temporal consistency and explosive coordination. Representative exercises include:

- Metronome tempo swings (progressively varied beats to entrain consistent downswing duration).

- Pause-and-accelerate (isolate transition timing by pausing at the top then accelerating through the hips).

- Medicine-ball rotational throws (multi-planar explosive practice to link hip-to-shoulder sequencing).

- Step-and-swing variations (perturbation of foot contact timing to train reactive sequencing).

Systematic progressions follow a staged model that moves from isolated timing control to integrated, context-rich execution. A practical three-stage progression is summarized below to guide protocol design and load prescription:

| Stage | Focus | Representative Drill |

|---|---|---|

| Isolation | Segment onset timing | Pause-and-accelerate |

| Integration | Coordinated sequence under tempo | Metronome swings |

| Application | Reactive sequencing & variability | Step-and-swing; live shot practice |

Monitoring must be outcome-focused and repeatable: clinicians should track both central tendencies (mean time-to-peak values) and variability (standard deviation of intersegmental lags) because reduced variability with preserved speed often signifies motor learning. Practical monitoring items include sensor-derived pelvis→thorax lag, downswing duration, clubhead time-to-peak speed, and subjective movement smoothness ratings. When improvements in timing metrics coincide with increased ball speed and reduced dispersion, the practitioner has strong evidence that neuromuscular progressions effectively improved sequencing rather than producing compensatory strategies.

Spinal Biomechanics and Injury Risk Mitigation: Lumbar Load Analysis, Movement Constraints and Rehabilitation Guidelines

Quantitative analysis of lumbar loading during the golf swing reveals a complex interplay of axial rotation, lateral bending and antero-posterior shear superimposed on high compressive demands during transition and early downswing. Peak instantaneous loads can exceed multiples of bodyweight when poor sequencing or abrupt deceleration occurs; such transient spikes are primary drivers of microtrauma in the lumbar motion segments. Anatomical considerations – including the segmented vertebral column, intervertebral discs and neural canal geometry – modulate tolerance to these loads, and degenerative conditions (e.g., spinal stenosis or facet arthropathy) further reduce the margin for repetitive stress (see clinical overviews from major spine resources). Kinematic profiling (3D motion capture) combined with force-plate and inertial-sensor kinetics provides the objective basis for identifying load-exposure patterns linked to elevated injury risk.

Movement constraints that consistently amplify lumbar stress are well characterized and amenable to technical correction. Common high-risk patterns include excessive early extension, pronounced lateral flexion through the ball, inadequate hip rotation, and poor sequencing between pelvis and thorax.These faults tend to concentrate forces on particular lumbar levels and increase shear. key high-risk constraints include:

- Early extension – forces the lumbar spine into repeated extension under load.

- Loss of pelvic dissociation – reduces energy transfer and increases spinal loading.

- Asymmetric weight shift – produces unilateral facet overload.

Mitigation requires an integrated approach combining swing modification, physical conditioning and load management. Technical interventions prioritize restored pelvis-to-thorax sequencing,reduction of lateral bending,and gradual development of clubhead speed through kinetic chain efficiency rather than increased lumbar torque. Conditioning focuses on the hips, gluteal complex, deep trunk stabilizers (multifidus, transversus abdominis) and eccentric control of the posterior chain to attenuate decelerative forces. Screening for pre-existing spinal conditions (e.g., canal compromise or symptomatic radiculopathy) should inform individualized practice volume and the tempo of technical drills; golfers with degenerative changes often require conservative limits on repetitive maximal-intensity swings and earlier emphasis on mobility and motor control retraining.

The rehabilitation pathway is staged, criterion-based and progressive, emphasizing pain control, restoration of motor control, graded loading and sport-specific reconditioning. Below is a concise phase table for clinician-coach coordination:

| Phase | Primary Goal | Key Interventions |

|---|---|---|

| Acute/Protection | Reduce pain, neurovascular safety | Relative rest, analgesia, gentle motor control |

| Subacute/Restoration | Restore mobility & baseline strength | Hip ROM, core activation, progressive loading |

| Return-to-Swing | Reintegrate swing mechanics safely | Segmental sequencing drills, graded swing reps, load monitoring |

Clinical criteria for progression should include pain-free functional tests, symmetrical hip rotation, adequate core endurance (timed holds), and validated swing metrics indicating restored sequencing and controlled lumbar motion.

Equipment Interaction and Impact Dynamics: Shaft and Clubhead Characteristics, Ball Flight Implications and Evidence Based Club Fitting Recommendations

Recent integrative analyses emphasize that the outcome of an impact event is a function of the coupled dynamics between the shaft and the clubhead rather than either element in isolation. Shaft bending, torsional compliance and kick-point location alter the timing of face closure and the dynamic loft delivered at impact; concurrently, clubhead mass distribution (CG location, MOI) governs how that delivered loft and face-angle result in effective launch conditions. Empirical biomechanical models show that small changes in shaft bend profile can shift effective loft by several degrees at mid-to-high swing speeds, directly affecting launch angle and backspin. In practical fitting this necessitates interpreting shaft properties as timing devices that either harmonize with or fight against a golfer’s release cadence.

Aerodynamic consequences of the equipment-body interaction are predictable when viewed through launch monitor metrics: clubhead speed, attack angle and face-to-path determine the initial conditions that aerodynamic forces will amplify or attenuate. Higher dynamic loft and increased backspin produce greater lift but increase aerodynamic drag and promote ballooning trajectories; conversely, lower spin can reduce carry but increase roll. Face angle, offset CG and heel-to-toe MOI modulate side-spin and the gear-effect, thereby influencing shot curvature and dispersion. wind-tunnel and CFD studies corroborate that marginal changes in spin rate (±200 rpm) and launch angle (±1°) are sufficient to change carry by several meters under typical conditions, which underscores the importance of fitting for target conditions, not just purely mechanical feel.

An evidence-based fitting protocol therefore centers on measured swing signatures and controlled on-course simulations. Recommended measured metrics include:

- Clubhead speed (baseline for flex and mass selection)

- Attack angle (informs loft and lie choices)

- Spin rate and launch angle (for aerodynamic matching)

- Face-to-path and tempo (for shaft kick-point and torque)

Translating metrics into prescriptions requires iterative validation: fitters should trial shafts with differing kick points and torque while holding head geometry constant,then test head variations (CG/loft/face design) with the shaft that best synchronizes with the player’s release. Objective validation with a launch monitor (e.g., doppler radar or photometric systems) and statistical analysis of dispersion is essential to seperate genuine performance gains from subjective feel.

Practical recommendations distilled from controlled studies and field fittings can be summarized succinctly for application by practitioners. Typical starting matches are shown below; these are guidelines to be refined by player-specific data and on-course feedback.

| Player Speed (mph) | Suggested Shaft Flex | Expected Launch | dispersion Focus |

|---|---|---|---|

| Under 85 | Senior or Ladies | Higher launch, higher spin | Stability & forgiveness |

| 85-100 | Regular | Balanced launch/spin | Control & feel |

| 100+ | Stiff/X-Stiff | Lower spin, penetrating ball | Consistency at high speed |

Additional fitting levers include lie angle adjustments to square the face at impact, grip size to optimize forearm torque transfer, and incremental changes to shaft length to fine-tune timing. Above all, an evidence-based fit integrates objective launch data, dispersion statistics, and repeatable biomechanical measurements to produce a setup that complements the player’s kinematic sequence rather than forcing compensations.

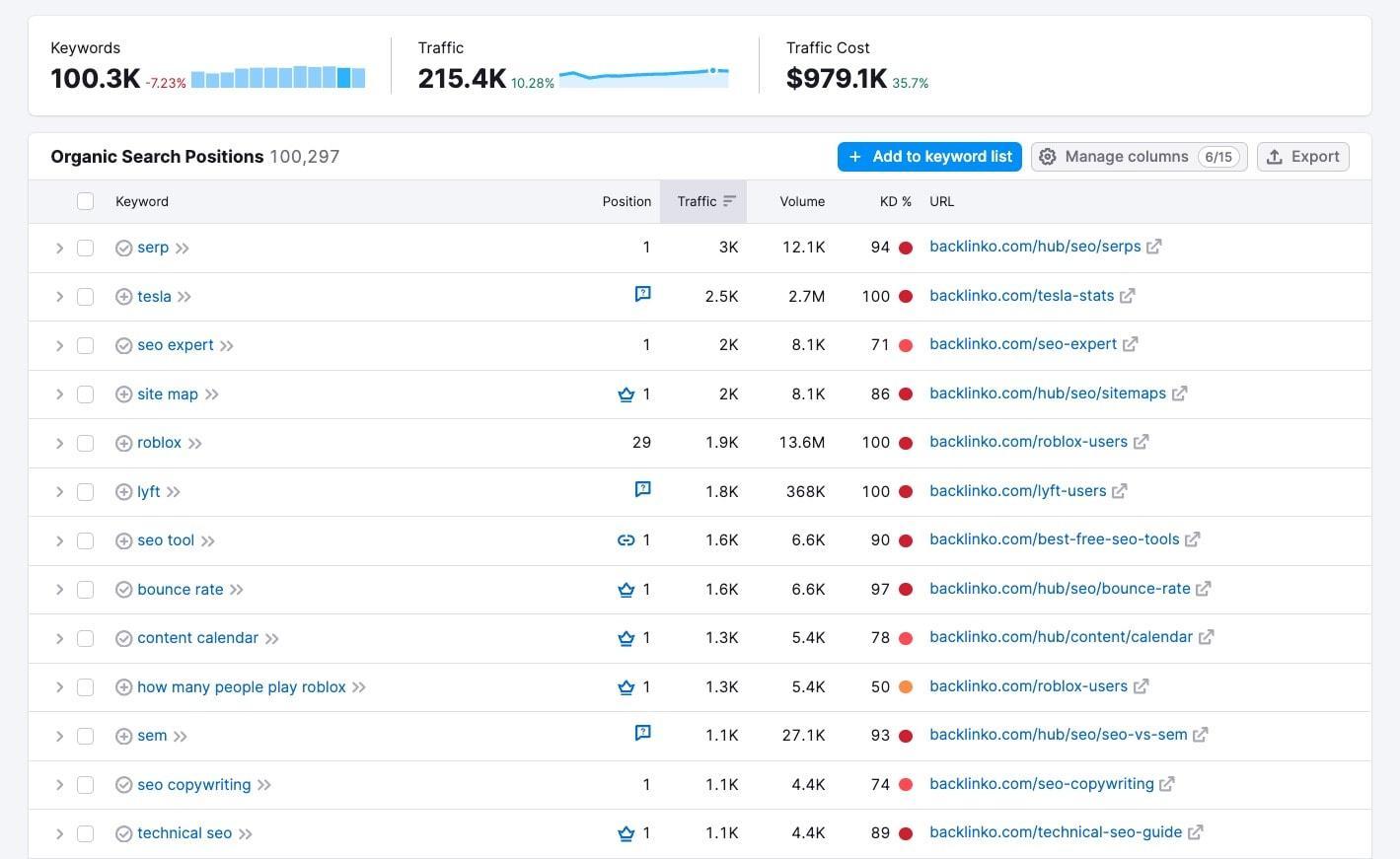

Translating Biomechanical Assessment into Coaching Practice: Motion Analysis Metrics, Individualized intervention Plans and Outcome Evaluation Methods

Contemporary coaching integrates quantitative motion analysis metrics to create actionable insights. Key kinematic and kinetic variables-hip-thorax separation (X‑factor), peak rotational velocities of pelvis and thorax, proximal-to-distal sequencing timing, club‑head speed, joint angular ranges (shoulder, elbow, wrist), and ground reaction force (GRF) profiles-form the backbone of biomechanical assessment. Measurement modalities typically include 3D optical motion capture, inertial measurement units (IMUs), force plates, and high‑speed video; each modality contributes different resolutions of temporal, spatial, and force data. To facilitate translation,coaches should prioritize metrics that are both reliable and sensitive to change in training contexts,for example:

- X‑factor & sequencing – sequencing errors frequently enough predict loss of distance and increase lumbar load.

- Peak rotational velocity – correlates with club‑head speed and transfer efficiency.

- GRF symmetry & impulse – informs lower‑limb contribution and balance strategies.

Assessment data must be synthesized into an individualized profile that informs a prioritized intervention plan. Coaches should compare athlete scores against normative ranges, within‑athlete baselines, and injury risk thresholds to assign intervention priorities (mobility, stability, strength, motor control). The following compact reference maps common measured deficits to straightforward intervention emphases for practical coaching use:

| Metric | common Deficit | Typical Intervention |

|---|---|---|

| X‑factor | Insufficient separation | Thoracic mobility + sequencing drills |

| GRF impulse | Low lateral force production | Hip/ankle strength + step/drive drills |

| Shoulder ROM | Restricted external rotation | targeted mobility + eccentric rotator cuff work |

Interventions should be specific, progressive, and testable: blend motor learning strategies (external focus, variable practice, constraint manipulation) with progressive strength and tissue capacity work. Effective coaching programs typically incorporate the following integrated elements:

- Technical drills that isolate sequencing and timing (e.g., slow‑motion segment linkage, impact‑focused reps).

- Physical preparation emphasizing force production, rate of force development, and eccentric control.

- Mobility/stability modules targeted to deficits revealed in the biomechanical profile.

- load management to progressively increase swing volume and intensity while respecting tissue adaptation rates.

Robust outcome evaluation couples objective re‑testing with performance and symptom tracking. Reassessments at predetermined intervals (e.g., 4, 8 and 12 weeks) should include the original motion metrics, club‑head speed, dispersion statistics, and athlete‑reported outcome measures (pain, function, confidence). Use statistical thresholds-minimal detectable change and effect size-alongside time‑series plots to distinguish meaningful adaptations from measurement noise. a multidisciplinary feedback loop (coach, biomechanist, S&C, medical) ensures that data drive iterative plan adjustments and that clinical risk markers are monitored until return‑to‑play criteria are consistently met.

Q&A

1) Q: what is meant by “biomechanics” in the context of golf swing performance?

A: Biomechanics is the application of mechanical principles to living systems to explain movement and forces acting on the body. In golf, biomechanics describes how segments, joints, muscles and the club interact to produce ball flight and how external forces (gravity, ground reaction) and internal forces (muscle tension, joint moments) govern swing motion. This conceptual framing-rooted in the multidisciplinary field of biomechanics described in foundational sources-provides the basis for kinematic, kinetic and neuromuscular analysis of the golf swing.

2) Q: What are the principal kinematic variables used to describe a golf swing?

A: key kinematic variables include segment positions and orientations (hip,thorax,shoulders,arms),joint angles (trunk rotation,shoulder ab/adduction,elbow flexion),angular velocities and accelerations of segments,temporal events (backswing duration,transition,downswing,impact,follow-through),intersegmental sequencing (proximal-to-distal activation),and the resultant clubhead path,face angle and clubhead speed at impact.

3) Q: How is the golf swing typically divided into kinematic phases for analysis?

A: Analysts commonly divide the swing into: address/set-up, backswing (early and late), top of backswing, transition, downswing (early and late), impact, and follow-through. Each phase has characteristic segmental motions and timing that are relevant for performance (e.g., energy transfer) and injury risk (e.g., loading at transition).

4) Q: What kinematic patterns are associated with higher clubhead speed and shot performance?

A: Consistent findings show that effective proximal-to-distal sequencing (pelvis rotation peak → thorax rotation peak → upper arm/forearm → club), high peak rotational velocities of the pelvis and trunk, maintained separation between pelvic and thoracic rotation (often quantified as the “X-factor”), rapid angular accelerations in the late downswing, and an optimized wrist-cocking/un-cocking sequence contribute to higher clubhead speed and controlled ball direction.

5) Q: What is the “X‑factor” and why is it vital?

A: The X-factor is the relative angular separation between pelvis and thorax at the top of the backswing. greater separation can increase elastic energy stored in the torso and enhance subsequent rotational acceleration, perhaps increasing clubhead speed. Though, very large or poorly controlled X-factors can raise lumbar stress and injury risk, so optimal magnitude depends on individual capacity and technique.

6) Q: What kinetic factors are moast relevant to golf swing performance?

A: Kinematic outcomes arise from kinetic drivers: ground reaction forces (magnitude and timing), joint moments (hip, lumbar, shoulder, elbow), power transfer across joints, and the net mechanical work produced by muscle-tendon units.Directional force application to the ground, coordinated force transfer between legs and through the trunk, and generation of rotational torque are all basic kinetic contributors to swing performance.

7) Q: How do ground reaction forces (GRFs) influence the swing?

A: GRFs provide the external impulse that enables generation of internal torques. Effective players use a coordinated build-up and transfer of vertical and horizontal GRFs-often showing a buildup on the trail leg during backswing and a shift/drive through the lead leg during downswing-to create rotational momentum and stabilize the body for efficient energy transfer to the club. Timing of peak GRFs relative to segmental rotation is critical.

8) Q: What neuromuscular dynamics underpin an effective swing?

A: Neuromuscular dynamics include muscle activation patterns (timing, amplitude, and sequence), intermuscular coordination, anticipatory postural adjustments, and motor control strategies for accuracy under variable environmental conditions. Electromyography (EMG) studies show phasic activation of hip rotators, trunk muscles (especially obliques and extensors), shoulder stabilizers, and forearm/wrist musculature timed to create proximal-to-distal energy transfer and to control clubface orientation.

9) Q: Which muscles are most critically important for generating rotational power and stabilizing the chain?

A: Primary contributors to rotational power include the hip rotators (gluteus medius/maximus, external rotators), pelvic stabilizers, abdominal obliques and transversus abdominis, lumbar extensors, and thoracic rotators. Shoulder stabilizers (rotator cuff, scapular stabilizers) and forearm/wrist muscles are essential for controlling the club and transferring distal power at impact.

10) Q: What common injury mechanisms are associated with golf swing biomechanics?

A: common mechanisms include excessive repetitive lumbar torsion and extension leading to low-back pain and lumbar disc stress; high shear and extension moments at the lead wrist and elbow (tendinopathy); rotator cuff overload from deceleration and repetitive external rotation; and hip or knee overload during forceful weight transfer. Poor sequencing, insufficient mobility, or rapid increases in swing intensity/frequency elevate risk.

11) Q: How can biomechanical analysis inform injury risk reduction?

A: objective analysis identifies aberrant kinematics (e.g., early extension, lateral flexion during transition), excessive joint moments, asymmetries in force application, or poor muscle timing. Interventions include technique modification to reduce harmful postures, tailored mobility and strength programs (e.g., thoracic rotation, hip internal/external rotation, gluteal strength, trunk endurance), load management and progressive conditioning, and neuromuscular training to improve sequencing and deceleration control.

12) Q: What assessment tools are used in golf swing biomechanics?

A: Common tools include three‑dimensional motion capture systems (optical marker-based), inertial measurement units (IMUs), high-speed video analysis, force plates to record GRFs, electromyography (EMG) for muscle activation, and instrumented club/launch monitors to measure clubhead speed, path, face angle, and ball data. Choice depends on research question, ecological validity, and resource constraints.

13) Q: What are the limitations of laboratory biomechanics when applied to on-course performance?

A: Laboratory setups may alter natural swing behavior due to markers, tethering, constrained space, or intentional testing protocols. Surface/club differences and psychological/environmental factors (pressure, stance variability on turf) also affect transfer. IMUs and hybrid lab-field protocols can increase ecological validity, but researchers must balance measurement precision with representativeness of play.

14) Q: What evidence-based training interventions improve swing mechanics and performance?

A: Interventions with supporting evidence include:

– Rotational power and medicine-ball rotational throws to improve proximal-to-distal sequencing and power.

– Strength training targeting hips, glutes, and trunk to increase force production and stability.

– Mobility work (thoracic rotation, hip internal rotation) to permit safer X-factor mechanics.

– Neuromuscular drills emphasizing sequencing (slow-to-fast swings, pause drills at transition).

– Eccentric training and deceleration drills for shoulder and elbow injury prevention.

Program design should be progressive, individualized, and include on-course or on-turf transfer practice.

15) Q: How should coaches integrate biomechanical findings into coaching practice?

A: Coaches should use objective metrics where available, but prioritize individualized assessment: identify limiting factors (mobility, strength, sequencing), prescribe targeted interventions, and use simple observable proxies (pelvis-thorax separation, swing tempo, weight-shift pattern) to monitor change. Collaborate with sport scientists and medical professionals when high loads or injury risk are present.

16) Q: What objective benchmarks or metrics are useful for practical coaching?

A: Useful metrics include clubhead speed and ball launch data (carry distance, spin), peak pelvis and trunk angular velocities, timing of peak segmental velocities (sequencing), GRF patterns and timing, and symmetry indices (left vs right). Benchmarks should be normalized to age/skill level and interpreted in context-absolute values vary widely across players.

17) Q: How does motor learning theory inform technique refinement?

A: Motor learning principles favor progressive, task-specific practice, variability that promotes adaptable movement solutions, externally focused cues (e.g., target-based) for better automaticity, and scheduled feedback to avoid dependency.Blocked practice may help early acquisition; variable practice and contextual interference enhance retention and transfer to play.

18) Q: What research gaps remain in golf-swing biomechanics?

A: Key gaps include long-term intervention trials linking specific biomechanical changes to performance and injury outcomes, normative databases across skill levels and ages, field-validated IMU algorithms for key metrics, and mechanistic studies on cumulative load and tissue adaptation in golfers.more work is needed to individualize “optimal” mechanics based on morphology and history.

19) Q: Are there contraindications or precautions when applying biomechanical corrections?

A: Yes. Major precautions include forcing ranges of motion beyond anatomical capacity, imposing high training loads without progressive conditioning, and applying one-size-fits-all technical fixes that conflict with an individual’s anatomy or injury history. Always screen for red-flag symptoms, and integrate medical/physiotherapy input when pain or pathology exists.

20) Q: What is a practical assessment protocol a coach or clinician can use to evaluate biomechanics and technique?

A: A practical protocol may include:

– Medical and training history, injury screening.

– Static mobility tests (thoracic rotation, hip internal/external rotation, ankle dorsiflexion).

- Strength/functional tests (single-leg squat,isometric hip and trunk strength).

– On-field observation of swing phases with high-speed video from frontal and down-the-line views.

– Simple force/weight-shift assessment (pressure mat or video observation).

– If available, IMU or launch-monitor data for clubhead speed and sequencing proxies.

use results to prioritize interventions (mobility, strength, technique) and re-test periodically.21) Q: How should findings from general biomechanics literature be applied to golf?

A: Apply foundational biomechanics principles-force generation/transfer, segmental sequencing, load tolerance-while accounting for sport-specific constraints (club as a long lever, precise strike requirements). Leverage multidisciplinary knowledge from biomechanics sources to design evidence-based assessments and interventions that respect individual variation and performance goals.

22) Q: What are recommended next steps for researchers and practitioners aiming to advance evidence-based golf biomechanics?

A: Collaborative work that links laboratory measures to on-course outcomes; randomized or controlled intervention trials of technique and conditioning programs; development and validation of portable measurement technologies (IMUs, wearable pressure sensors) for coaches; and creation of normative, injury-linked datasets to inform individualized risk-benefit decisions.

For further foundational reading on biomechanics principles that underpin the above concepts, consult comprehensive biomechanical reviews and educational resources from university biomechanics programs and applied kinesiology texts. These provide the theoretical and methodological grounding used to interpret kinematic, kinetic and neuromuscular data in sport-specific contexts.

a biomechanical viewpoint on the golf swing synthesizes kinematic description, kinetic causation, and neuromuscular control to provide a rigorous basis for technique refinement and injury mitigation. By quantifying segmental motions, joint moments, ground-reaction forces, and muscle activation patterns, researchers and practitioners can move beyond anecdote to evidence-based adjustments that enhance performance while respecting the anatomical and physiological constraints of individual golfers. Such analyses also clarify trade-offs between ball-striking objectives (e.g., clubhead speed, accuracy, spin) and musculoskeletal loading that underlie manny overuse injuries.

Translational progress will depend on interdisciplinary collaboration that couples high-fidelity measurement (e.g., 3D motion capture, force platforms, wearable inertial sensors, EMG) with robust biomechanical modeling and longitudinal field studies. Equally critically important is the integration of these data into coaching frameworks that are individualized, context-sensitive, and cognizant of the athlete’s training history and injury profile. Coaches, clinicians, and sport scientists should therefore adopt a systems-level mindset: using biomechanics to inform targeted interventions while monitoring outcomes across performance and health domains.

Future research should prioritize ecological validity, larger and more diverse samples, and the development of accessible analytic tools that bridge laboratory insights and on-course application. As the field advances, the ongoing translation of biomechanical evidence into coaching practice offers a pathway to optimize both the efficacy and safety of swing technique, ultimately promoting sustainable performance gains across levels of play.By grounding instruction and rehabilitation in the principles of biomechanics, the golf community can more reliably refine technique, reduce injury risk, and support long-term athletic development.

Biomechanics and Technique in Golf Swing Performance

What is biomechanics and why it matters in the golf swing

Biomechanics is the scientific study of movement and the mechanical principles that govern living bodies. As described in standard references on biomechanics, it combines mechanics with biological systems to explain how forces, motion, and structure interact.Applied to golf, biomechanics translates into measurable targets for posture, rotation, sequencing and force production that lead to better ball striking, greater distance and improved shot consistency.

Key biomechanical principles for a powerful, repeatable golf swing

Optimizing the golf swing requires aligning technique with biomechanical principles. Below are the foundational ideas coaches and sports scientists monitor:

- kinetic chain & sequencing - Efficient energy transfer from the ground through the legs, hips, torso, shoulders, arms and finally to the clubhead.

- Ground reaction forces (GRF) – Using the ground to generate force, especially during the transition and downswing, increases clubhead speed.

- Rotational dynamics & torque – Creating stored rotational energy (separation between hip and shoulder turn) yields more power at impact.

- Centre of mass and weight shift – Balanced weight transfer optimizes impact position and reduces inconsistent strikes.

- Clubface control & wrist mechanics – proper grip, wrist hinge and release control face angle at impact for accuracy.

- Timing and tempo – Consistent cadence improves repeatability and maximizes the kinetic link.

Kinetic chain in practice

Think of the swing as a sequence of links: feet → legs → hips → torso → shoulders → arms → hands → club. If any link is late or underpowered, performance drops.Effective sequencing produces a smooth acceleration curve culminating in impact.

technique breakdown: grip, stance, posture and setup

Small setup details produce large biomechanical differences. Below are practical, evidence-based coaching cues:

- Grip - Neutral to slightly strong grip helps square the clubface at impact. Maintain light-to-moderate grip pressure (around 4-6 out of 10) to allow wrist hinge and release.

- Stance & alignment - Feet shoulder-width for a mid-iron; wider for driver.Align shoulders and feet parallel to the target line for better rotational balance.

- Posture – Hinge from the hips with a slight knee flex. Spine tilt should allow free shoulder rotation without collapsing in the lower back.

- Ball position – Move the ball slightly forward in the stance for longer clubs (driver) and central for mid-irons to influence launch and spin.

- Balance – Keep weight distributed between both feet with a slight pressure toward the balls of the feet to enable force production from the ground.

The swing phases and biomechanical targets

Breaking the swing into phases helps isolate biomechanical targets and practice consistent mechanics.

1. Address & setup

- target: Neutral spine, balanced base, correct ball position, and relaxed grip.

2. Backswing

- Target: Smooth coil – 90° shoulder turn for many players, good wrist hinge (~90° wrist **** in many cases), and maintained spine angle.

- Coaching cue: “Turn your chest away from the target while keeping your lower body stable.”

3. Transition

- Target: Start the downswing with lower body momentum – hips rotate toward the target while maintaining upper-body torque.

- Metric: Early lateral shift of the pelvis and a slight compression into the ground to produce GRF.

4. Downswing & impact

- Target: Proper sequencing – hips, torso, shoulders, arms, hands. Clubhead accelerates through impact; clubface square to target.

- Impact cues: Slight forward shaft lean for irons, centered lower-body mass behind the ball, and stable head position.

5. Follow-through

- Target: Full rotation with balanced finish on the lead leg; follow-through shows quality of the kinetic chain.

Motion capture, force plates, and evidence-based measurement

Modern coaching leverages motion capture systems, high-speed cameras, and force plates to quantify the swing. these tools measure:

- Shoulder and hip rotation angles

- Sequencing timing between body segments

- Ground reaction force peaks and timing

- Clubhead speed, attack angle, and dynamic loft at impact

Using objective data, coaches can prescribe drills that correct specific deficits (e.g., late hip rotation, low GRF, or poor wrist release). Published biomechanics resources define standards and methodologies for these measurements and support data-driven training plans.

Practical drills and training to improve biomechanics

Below are high-impact drills aligned with biomechanical goals. Use them during range sessions and track improvements with video or simple launch monitor metrics (clubhead speed, smash factor, ball speed).

| Drill | Target | Coaching cue |

|---|---|---|

| Step-down to hit | Sequencing / weight transfer | “Step and rotate – let the hips lead” |

| Med ball rotational throws | Power & hip-shoulder separation | “Explode from your core toward the target” |

| Alignment stick rotation | Shoulder turn accuracy | “Turn until you feel a stretch across the chest” |

| impact bag hits | Impact position / shaft lean | “Hit the bag with forward shaft lean and balanced finish” |

Tempo and rhythm drills

- Use a metronome or counting pattern (e.g.,1-2 for backswing,1 for transition) to ingrain consistent tempo.

- Practice slow-motion swings to reinforce the sequencing and feel of proper timing.

Common swing faults from a biomechanical perspective and fast fixes

Understanding the mechanical cause of a fault leads to specific corrective action.

- Early extension (stand-up at impact) – Cause: Loss of hip hinge or timing. Fix: Impact bag or weighted club drills to maintain posture through impact.

- overactive hands and cast – Cause: Poor wrist hinge or early release. Fix: Pause at the top and feel delayed release; use half-swings to groove the feel.

- Reverse pivot (weight on toes at impact) – Cause: Improper weight shift or balance. Fix: Step-down drill or feet-together swings to promote stable base.

- Slice (open clubface at impact) – Cause: Weak release or out-to-in swing path. Fix: Path drills with alignment sticks and grip adjustment for face control.

- Hook (closed clubface) – Cause: Over-rotation of forearms or excessively strong grip. Fix: Neutralize grip and practice half-swings focusing on face awareness.

Benefits and training recommendations

Applying biomechanics to your practice yields measurable performance gains:

- Improved clubhead speed and drive distance by optimizing ground force and rotational torque.

- Greater consistency and accuracy through repeatable sequencing and correct impact positions.

- Injury prevention by balancing mobility and stability and avoiding compensatory movements.

Recommended training plan (weekly):

- 2 range sessions focused on technique (30-45 minutes each) using drills for sequencing and impact.

- 2 strength & mobility sessions (30-60 minutes) emphasizing rotational power, hip mobility and thoracic spine mobility.

- 1 session with video or launch monitor feedback to check measurable targets (clubhead speed,attack angle,smash factor).

Case study: How biomechanical coaching improved a mid-handicapper

Player profile: 15-handicap amateur with inconsistent drives and a 10-15 yard gap in distance between best and average drives.

- Initial assessment: Short shoulder turn,limited hip rotation,early release and weak ground-force timing.

- Intervention: Six-week program with rotational mobility drills, med-ball throws, step-down sequencing drill, and impact-bag work. Sessions included video capture and weekly metrics from a launch monitor.

- Outcome: Clubhead speed increased by 6 mph, average drive distance improved by ~20 yards, and dispersion (accuracy) tightened substantially. Player reported greater confidence and less fatigue due to improved mechanics.

How to measure progress and what to track

Quantify improvements rather than relying solely on feel. Track these metrics:

- Clubhead speed and ball speed

- Smash factor (efficiency)

- Launch angle and spin rate (for distance optimization)

- Sequence timing (if using motion-capture) or simple video comparisons of key positions

- Consistency: standard deviation of dispersion on a trackman/launch monitor session

Practical tips for integrating biomechanics into your practice

- Start with setup and posture – small changes have big ripple effects.

- record your swing at regular intervals (weekly or bi-weekly) and compare angles/positions.

- Use simple tools (alignment sticks, med ball, impact bag) before moving to complex tech.

- Prioritize mobility and strength that support the swing - thoracic rotation, hip mobility and single-leg stability are high-impact areas.

- Work with a coach who can interpret data and provide measurable drills – data without coaching is just numbers.

Further reading and resources

For foundational background on biomechanics, consult authoritative overviews that define the science and methods used to study human motion. these resources bridge theory and practice and are widely used in sports biomechanics research and coaching.