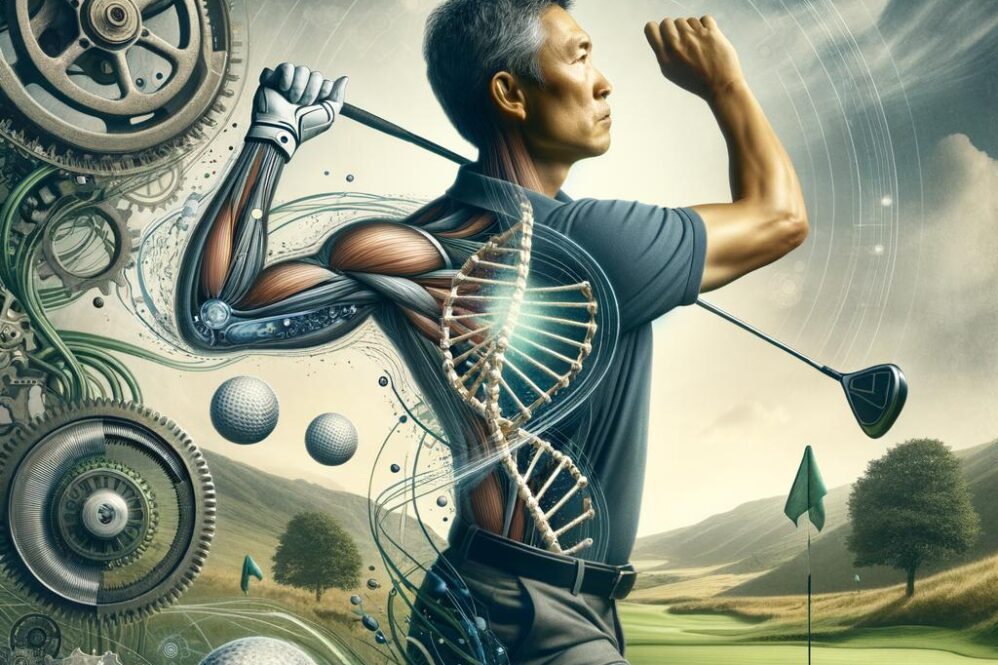

The follow-through phase of the golf swing represents more than a cosmetic finish; it is the terminal expression of a coordinated sequence of kinematic and kinetic events that determine ball trajectory, dispersion, and repeatability.Framed within the discipline of biomechanics-the request of mechanical principles to living organisms [1,4]-analysis of the follow-through illuminates how segmental sequencing, joint kinetics, ground reaction forces, and neuromuscular control together govern the transfer of energy from the golfer to the club and ultimately to the ball. Rigorous consideration of these elements is essential for understanding how subtle alterations in timing, posture, and force application translate into measurable changes in accuracy and precision.

Contemporary biomechanical perspectives emphasize the proximal-to-distal activation pattern, conservation of angular momentum, and optimal release mechanics as central determinants of an effective follow-through. Empirical and theoretical frameworks developed across movement sciences provide tools for quantifying these phenomena, including three-dimensional kinematics, inverse dynamics, and force-plate analysis [2]. Integrating such methods with on-field performance metrics enables the disambiguation of skill-related variability from technique-inherent constraints, thereby supporting targeted interventions to improve consistency.

Beyond performance optimization, the follow-through has implications for injury risk and long-term motor learning. Excessive compensatory motions, poor deceleration strategies, or maladaptive sequencing can increase joint loading and tissue strain even when immediate ball flight appears satisfactory. Consequently, a biomechanically informed approach balances the pursuit of precision with principles of safe, reproducible movement patterns.

this article synthesizes current biomechanical theory and applied research to characterize the mechanistic role of the follow-through in golf accuracy. It outlines key measurable variables, reviews evidence linking follow-through mechanics to shot outcomes, and translates findings into practical recommendations for instruction, training, and biomechanical assessment.

Kinematic Sequencing of the Golf Follow Through: Timing and Coordination of Pelvis Trunk and Upper Limb

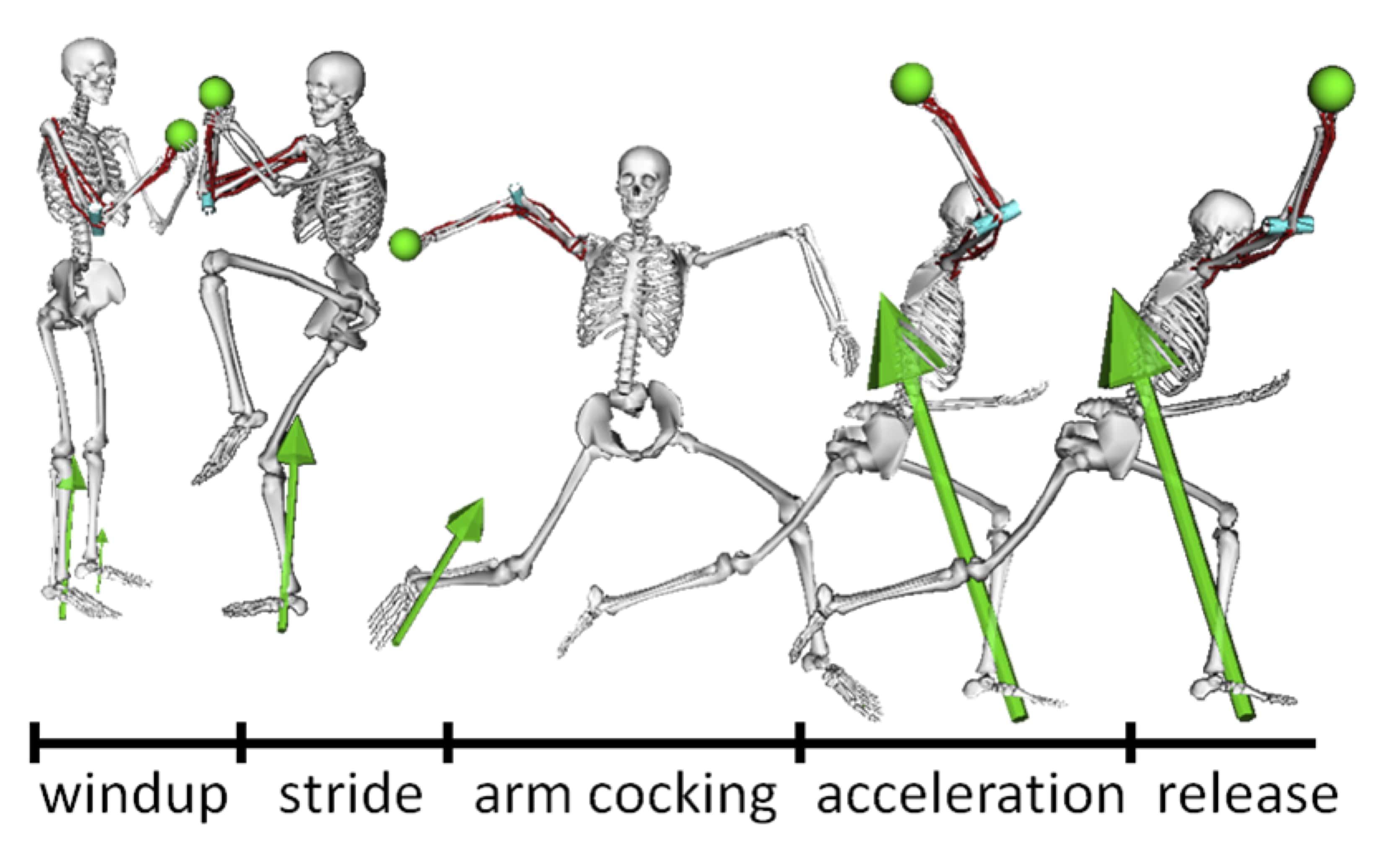

Efficient energy transfer in the follow‑through is governed by a clear proximal‑to‑distal kinematic sequence: the **pelvis** initiates and modulates rotational momentum, the **trunk** acts as the principal transmitter of angular velocity, and the **upper limb** completes the sequence by extending and guiding the club through release. When executed with appropriate timing, this sequence preserves clubhead speed while stabilizing clubface orientation at and after impact, thereby reducing angular deviation of the ball flight and enhancing accuracy. Key biomechanical goals during the follow‑through are maintenance of rotational continuity, controlled deceleration of proximal segments, and minimal compensatory motions in the lead arm and wrist.

Quantitative coordination is most often assessed by the relative timing of peak angular velocities and by inter‑segmental phase lag. A mechanically optimal pattern shows a systematic delay such that the **pelvis** reaches peak rotational velocity first, followed by the **trunk**, and finally the **upper limb/club**. This temporal staggering (proximal → distal) creates an impulse cascade that maximizes distal velocity while minimizing unwanted torque at the wrist. Additional metrics that correlate with shot consistency include: peak pelvis‑to‑trunk rotation ratio, trunk axial rotation relative to vertical ground reaction force, and the timing of wrist pronation relative to arm extension. Deviations from this coordinated pattern-early trunk deceleration or premature arm collapse-are associated with loss of face control and lateral dispersion.

Translating sequence analysis into practice requires targeted coordination drills and cueing. Useful interventions prioritize temporal control of segmental rotation and proprioceptive awareness of follow‑through positions. Examples include:

- Pelvis‑first drill: slow, exaggerated pelvis rotation through impact to reinforce proximal initiation and reduce arm‑dominated motion;

- Medicine‑ball throw: rotational throws emphasizing trunk‑to‑arm transfer to train peak velocity timing;

- Step‑through progression: stepping into the follow‑through to habituate ground reaction timing and pelvis deceleration;

- Mirror‑feedback sequences: brief high‑speed video review focusing on trunk alignment and arm extension during the first 200 ms post‑impact.

These modalities are designed to re‑pattern the central timing relationships rather than simply increasing strength or adaptability.

Below is a concise reference of approximate temporal windows and peak variables observed in high‑performance swings (values are generalized and subject to individual variation). Use these values as training targets, not absolutes.

| Segment | Typical Peak Timing (ms relative to impact) | Primary Peak Variable |

|---|---|---|

| Pelvis | -20 to +30 | Axial rotational velocity |

| Trunk | +10 to +80 | Torso angular velocity |

| Upper limb / Club | +60 to +150 | Clubhead linear/angular velocity |

Careful measurement using high‑speed kinematics and synchronized force platforms is recommended to individualize these targets and to quantify improvements in timing and accuracy.

Role of Trunk Rotation and Core Stability in Producing Consistent clubhead speed

Effective transfer of rotational energy from the pelvis through the thorax to the shoulders is the principal mechanism by which peak and consistent clubhead velocity are generated. Biomechanical analyses indicate that temporal sequencing-often described as the proximal-to-distal kinematic chain-requires precise timing of trunk rotation relative to lower-limb drive. When the trunk rotates too early or too late,angular impulse delivered to the upper extremity is diminished,producing variable clubhead speeds and increased dispersion. Quantitatively, small deviations in trunk angular velocity (±10-15%) can translate into measurable reductions in clubhead speed and shot consistency.

Core stability functions as the stabilizing scaffold that permits efficient force transmission and minimizes energy leaks. From a mechanical perspective, deep stabilizers (e.g., transversus abdominis, multifidus) provide segmental stiffness while superficial rotators (external obliques, erector spinae) generate torque. Training and conditioning studies demonstrate that improved core stiffness correlates with reduced intra-swing variability and higher repeatability of peak velocities. Strategies that enhance anticipatory postural adjustments and reactive stiffness result in better conservation of rotational momentum during the release and follow-through phases.

Practical components of technique and conditioning that underpin consistent outcomes include: timing of pelvis-thorax separation, controlled eccentric deceleration of the torso, and coordinated breath-control to modulate intra-abdominal pressure. Recommended motor patterns emphasize a controlled continuation of rotation through impact rather than abrupt halting at contact,which preserves angular momentum into the follow-through. key considerations for coaches and clinicians are summarized below:

- Pelvic timing drills – reinforce lag between hip rotation initiation and torso rotation.

- Rotational stability exercises – anti-rotation and resisted chops to increase stiffness under load.

- Eccentric control work – slow deceleration to minimize abrupt energy dissipation after impact.

The following table presents concise markers used in assessment and training progression for trunk rotational performance and core stability, useful for clinicians integrating biomechanical feedback into practice.

| Measure | Ideal Range/Goal | Training Focus |

|---|---|---|

| Pelvis‑Thorax Separation (°) | 20-30° at peak | Sequencing drills |

| Trunk Angular Velocity (°/s) | Consistent within ±10% | Reactive stability |

| Core Stiffness (qualitative) | High, low variability | Anti‑rotation strength |

optimal Arm Extension and Release Mechanics for launch Angle Control and Accuracy

Precise arm extension through impact serves as a primary determinant of the clubhead’s later trajectory by modulating the effective lever length and the timing of peak clubhead velocity. During the final phase of the swing the lead arm should approach near-full extension without sacrificing shoulder stability; this configuration maximizes tangential velocity while preserving a predictable strike point on the clubface. From a biomechanical perspective, the temporal relationship between extension and trunk deceleration governs how energy is transferred from proximal segments to the club-earlier extension with inadequate trunk rotation tends to lower launch angle and increase side spin, whereas delayed extension often reduces clubhead speed and lateral consistency. Key mechanical variables to monitor include extension angle at impact, extension velocity, and the relative timing of trunk-shoulder deceleration.

Wrist and forearm release mechanics critically refine the face orientation and vertical loft at ball contact. Controlled pronation of the lead wrist during the final degrees of the swing rotates the clubface toward a square position while subtly increasing dynamic loft when combined with proper shaft lean. Excessive or premature pronation, though, can induce face closure and produce low, hooked trajectories; conversely, late or insufficient pronation increases open-face tendencies and promotes slices.practical motor cues that help integrate timing and magnitude of release include:

- “Lead elbow long and quiet” – encourages a stable extension platform for consistent geometry.

- “Rotate the forearm through impact” – promotes controlled pronation to square the face.

- “Finish with chest facing target” – ensures trunk rotation supports rather than disrupts release timing.

Intersegmental coordination is foundational: the kinetic chain must be organized so that pelvic and thoracic rotation provide the inertial impetus, while the arm and wrist execute the precise final adjustments. The following concise table summarizes empirically useful target ranges and their expected effect on launch and accuracy when executed within a controlled swing sequence.

| Metric | Target Range | Expected Launch Effect |

|---|---|---|

| Lead arm extension at impact | ~150°-175° (relative) | Higher clubhead speed, consistent strike |

| Forearm pronation through impact | 10°-25° excursion | Face squareing; fine-tuned launch angle |

| Release angular velocity | Moderate peak, well-timed | Reduced dispersion; stable spin rates |

From a training and coaching standpoint, targeted interventions should combine strength and neuromuscular drills with augmented feedback to entrench efficient release patterns. Progressive overload of shoulder and scapular stabilizers develops the capacity to maintain near-full extension under high velocity; eccentric-focused forearm work refines controlled pronation speed.Drill prescriptions that improve timing-such as slow-motion impact repetitions, tempo-controlled half-swings, and live video/launch monitor feedback-promote the motor learning necessary for consistent launch-angle control and improved shot accuracy. For practitioners, the emphasis should remain on reproducible sequencing rather than isolated joint extremes, with measurable metrics used to evaluate intervention efficacy.

Wrist Pronation and Supination Dynamics and Their Impact on Clubface Orientation

Distal forearm rotation is a primary contributor to the final clubface trajectory during the follow-through. Anatomically, rotation arises from relative motion between the radius and ulna and is transmitted through the wrist complex to the club shaft; because the hand-club system lies at the distal end of a rapidly moving kinetic chain, even modest angular excursions in forearm rotation can produce disproportionate alterations in face angle at and after impact. From a biomechanical perspective, the rotational inertia of the club amplifies small pronation/supination torques generated by the forearm musculature, making fine neuromuscular control of these rotations critical for consistent face alignment.

Temporal sequencing governs whether forearm rotation contributes to a square, open, or closed face at impact. If internal rotation (pronation) is initiated early and accelerated through impact without being counterbalanced by wrist extension control, the face tendency is to close; conversely, excessive external rotation (supination) late in the downswing can leave the face open. These kinematic patterns interact with proximal segment motion (torso rotation and elbow extension) such that the same magnitude of wrist rotation will have different effects depending on segmental timing. In kinetic terms, peak pronation/supination angular velocity and the moment arm relative to the clubshaft determine the net torque transmitted to the clubface, thereby influencing spin axis and lateral dispersion.

Coaching and training should therefore emphasize both magnitude and timing of forearm rotation, with targeted exercises to isolate neuromuscular control of the rotational degrees of freedom.Recommended interventions include:

- Towel-grip release drill: promotes gradual pronation through impact while preserving wrist stability.

- Split-hand tempo swings: reduce shaft leverage to sensitize the golfer to small rotational errors.

- Band-resisted pronation/supination: builds eccentric control of forearm rotators to resist unwanted late snappy rotations.

These drills are designed to integrate proprioceptive feedback with functional timing so that small corrective rotations are executed at the appropriate instant in the follow-through.

| Forearm State | Typical face outcome | Coaching Cue |

|---|---|---|

| Controlled pronation through impact | Neutral to slightly closed | “Rotate palms down smoothly” |

| Excessive early pronation | Closed face – draws/hooks | “Delay forearm roll” |

| Late supination spike | Open face – fades/slices | “Feel the face square at impact” |

Integrating these forearm rotation strategies with trunk rotation and appropriate wrist hinge yields the most reliable clubface control; optimization therefore requires concurrent training of distal precision and proximal timing under sport-specific velocity conditions.

Muscle Activation Patterns During the Follow Through and Targeted Strengthening Protocols

The follow-through phase exhibits a characteristic sequence of muscle activations that reflects both residual power transfer and active deceleration. Core rotators (external and internal obliques) and the lumbar paraspinals maintain rotational momentum and provide a controlled dissipation of angular velocity; the gluteal complex and hip external rotators continue to stabilize the pelvis and transfer kinetic energy up the kinematic chain. In the upper limb, the posterior shoulder (rotator cuff and posterior deltoid) and scapular stabilizers (middle/lower trapezius, rhomboids) govern humeral deceleration and maintain glenohumeral integrity, while forearm pronators and wrist extensors/flexors modulate clubface orientation. This pattern is characterized by a coordinated shift from concentric propulsion to eccentric braking with important co‑contraction across trunk and shoulder musculature to optimize accuracy and limit injurious shear forces.

Targeted conditioning should therefore prioritize multiplanar strength, controlled eccentric capacity, and high‑velocity neuromuscular coordination. Recommended interventions include medicine‑ball rotational throws and resisted chops for power and transverse plane rate of force development; Pallof presses and anti‑rotation drills for isometric trunk stability; single‑leg Romanian deadlifts and lateral lunges for pelvic control and hip deceleration; and rotator cuff/scapular retraction work with therabands or light dumbbells to preserve shoulder timing. For wrist and forearm control, incorporate pronation/supination drills and eccentric wrist curls.Training variables should follow a periodized model: 2-4 sets, 6-12 reps for hypertrophy/strength phases; 3-6 reps at maximal intent for power drills (3-5 explosive throws per set); and 2-3 sets of 8-12 slow eccentrics for deceleration capacity. Progressive overload and movement specificity (speed, plane, and range) are essential to transfer gains to on‑course performance.

Clinical context must guide implementation.Athletes with chronic low‑back symptoms should have rotational load and end‑range extension progressed cautiously and may benefit from supervised back‑specific rehabilitation (see clinical exercise guidance). Medications and systemic conditions can alter muscle activation and recovery: such as, centrally acting muscle relaxants (e.g., baclofen) may reduce coordination and strength, and statin therapy (e.g., rosuvastatin) can present with myalgias or, rarely, rhabdomyolysis-both conditions necessitate medical review before intensifying training. Individuals with neuromuscular disorders often demonstrate altered recruitment patterns and will require tailored programs developed with a specialist. In sum, incorporate screening for pain history, current medications, and neuromuscular status prior to prescription; when in doubt, refer to medical or physical‑therapy professionals for individualized modification (see resources from clinical practice guidelines).

Below is a concise reference matrix linking primary muscle groups to their functional role in follow‑through and exemplar exercises for targeted strengthening and control.

| Muscle group | Functional role | Exmaple exercise |

|---|---|---|

| Obliques / paraspinals | Sustain rotation and eccentric control | Pallof press; med‑ball rotational throw |

| Gluteus maximus / medius | Pelvic stabilization and force transfer | Single‑leg RDL; lateral band walk |

| Rotator cuff / scapular stabilizers | Deceleration and shoulder alignment | External rotation with band; prone T/Y |

| Forearm pronators / wrist muscles | Clubface control and fine deceleration | Eccentric wrist curls; pronation/supination |

Ground Reaction Forces and Lower Limb Contribution to Balance and Shot Precision

During the terminal phase of the swing the lower extremities act as the primary interface between the golfer and the ground, converting muscular effort into measurable external forces that determine post‑impact kinematics. Three orthogonal components of the ground reaction force (vertical, anterior-posterior, mediolateral) exhibit distinct temporal profiles: a rapid vertical impulse near impact that contributes to clubhead speed maintenance and launch characteristics; a braking/propulsive anterior-posterior component that modulates rotational deceleration and forward momentum transfer; and smaller but critical mediolateral forces that preserve base stability. Quantifying these components with force plates reveals that precise timing and magnitude of each vector are predictive of launch direction variability and dispersion patterns.

foot pressure patterns and center‑of‑pressure (CoP) trajectories provide mechanistic links between limb muscle function and shot precision. Front‑foot (lead) loading promptly after impact stabilizes the torso and attenuates undesired lateral rotation, while the trail foot provides a transient braking impulse that shapes axial deceleration. Key musculature-quadriceps and gluteus maximus for extension and support, gluteus medius for frontal‑plane stabilization, and the triceps surae for ankle stiffness modulation-works in coordinated concentric/eccentric sequences to control cop excursions. excessive CoP drift or uncontrolled mediolateral excursions correlate with increased yaw variability and lateral dispersion of ball flight.

Applied interventions should target both force production and neuromuscular control to reduce shot scatter. Recommended emphasis areas include:

- Stance optimization: adjust base width to suit individual anthropometry and desired CoP path.

- Eccentric strength training: develop controlled deceleration of hip rotators and knee extensors to stabilize the follow‑through.

- Plyometric and reactive drills: enhance rapid force transfer and improve timing of vertical impulse generation.

- Balance and perturbation tasks: reduce mediolateral CoP variability under rotational loads.

- Instrumented feedback: use pressure mats or force plates to monitor CoP and GRF timing during practice.

Empirical relationships between GRF components and shot outcomes can be summarized succinctly for coaching translation.

| GRF Component | Primary Mechanical Role | typical Performance Effect |

|---|---|---|

| Vertical | Support and upward impulse near impact | Higher launch / increased carry |

| Ant.-Post. | Propulsion/braking of COM | Influences spin and forward momentum control |

| Mediolateral | Frontal‑plane stabilization | Reduces lateral dispersion |

Integrated training that combines targeted strength, reactive power, and balance control-guided by objective GRF/CoP measurements-yields the most consistent reductions in shot dispersion and improvements in precision.

Applied Coaching Interventions and drills to Reinforce Biomechanically Efficient Follow Through

Applied interventions should target the mechanical contributors identified in biomechanical analyses-primarily **trunk rotation timing**, **lead-arm extension**, and **wrist pronation through impact**-while respecting motor-learning principles. Coaches are encouraged to couple kinematic targets with clear, observable outcome metrics (clubhead path, clubface orientation, and launch conditions) to create measurable objectives. Emphasize an **external focus** of attention (e.g., target line and flight) and graded task difficulty to promote transfer; brief, specific feedback that aligns with a player’s current motor capabilities yields better retention than long-form technical monologues.

Practical drills should be simple, repeatable and scalable. Useful examples include:

- “Finish Position Freeze” – execute full swings and hold the follow-through for 2-3 seconds to ingrain trunk rotation and arm extension alignment; cue: “finish tall, chest toward target.”

- Lead-Arm Extension Band Drill – use a light resistance band anchored behind the player to bias extension through impact; cue: “push the handle forward, keep the lead arm straight.”

- Wrist Pronation Tape Drill – place a short strip of tape on the shaft to provide visual feedback of shaft rotation during the follow-through; cue: “rotate the knuckles down after impact.”

- Controlled Tempo Ladder – vary backswing-to-downswing tempo using metronome cues to stabilize timing of trunk rotation and weight shift; cue: “smooth transition, accelerate through.”

Coaching delivery should integrate objective feedback modalities-high-speed video, launch monitor metrics, and inertial sensors-to provide immediate, concise KPIs for trajectory and clubface behavior. Apply a constraints-led approach: manipulate task, environment, or equipment constraints to encourage self-organization of the follow-through (e.g., shorter clubs, reduced target distance, or variable lies).Progress from blocked repetitions for early skill acquisition to random practice for retention and transfer, and schedule periodic reassessment sessions to adjust intervention load and complexity. Emphasize safety and progressive tissue loading when prescribing rotational and pronation drills.

| Drill | Primary Target | Coaching Cue |

|---|---|---|

| Finish Position Freeze | Trunk rotation & posture | “Finish tall, chest toward target” |

| Lead-Arm Extension Band | Arm extension through impact | “Push the handle forward” |

| Wrist Pronation Tape | Shaft rotation & release | “Rotate knuckles down after impact” |

| Tempo Ladder | Timing of rotation | “Smooth transition, accelerate through” |

Integrate these drills into microcycles (2-3 focused sessions/week) with objective checkpoints (video + launch monitor) to track improvements in launch angle, spin, and dispersion.

Q&A

1. What is meant by “biomechanics” in the context of an effective golf follow‑through?

Answer: Biomechanics is the application of mechanical principles to biological systems to understand movement, forces, and structure (see [1], [4]). In the golf follow‑through, biomechanical analysis examines how body segments, joints, muscles, and external forces interact during and after ball impact to influence clubhead trajectory, launch conditions, and subsequent athlete load and injury risk (see [3]).

2. Why is the follow‑through important for ball flight and accuracy?

Answer: The follow‑through reflects the kinematic and kinetic outcomes of the downswing and impact. Proper follow‑through is typically the consequence of correct sequencing, joint angular velocities, and force transfer; deviations in follow‑through often indicate errors in timing, clubface orientation at impact, or compensatory motion that can alter launch angle, spin, and lateral dispersion. Thus, follow‑through characteristics are both an outcome metric and a contributor to consistent shot mechanics.

3. Which body segments and joint actions are most influential during the follow‑through?

Answer: Key contributors include:

– Trunk (thorax/pelvis) rotation and deceleration, which govern proximal‑to‑distal energy transfer.

– Lead (left for right‑handed) arm extension and shoulder mechanics that influence club arc and path.

– Lead wrist radial/ulnar deviation and forearm pronation/supination that affect clubface rotation.

– lower extremity force generation and ground reaction force (GRF) transmission through hips and legs that supply the initial impetus and stability.

Effective follow‑through reflects coordinated action among these segments with appropriate angular velocities and timing.

4. What kinematic and kinetic metrics are used to quantify follow‑through effectiveness?

Answer: Common metrics include:

– Angular velocities of pelvis, trunk, shoulders, elbows, and wrists.

– Timing of peak angular velocities (segmental sequencing).

– Joint angles at impact and during follow‑through (trunk tilt, shoulder plane, wrist angles).

– Ground reaction forces and center‑of‑pressure progression.

– Joint moments and power profiles (hip and trunk extension moments; rotational power).

– Clubhead speed and clubface orientation at impact (launch dynamics).

These measures are obtained with motion capture, force plates, and inertial sensors.

5. How does proximal‑to‑distal sequencing relate to an optimal follow‑through?

Answer: Proximal‑to‑distal sequencing - the sequential activation and peak velocity from larger,proximal segments (hips/pelvis) to more distal segments (trunk → shoulders → arms → wrists → club) – maximizes transfer of angular momentum and mechanical power to the club. A well executed follow‑through shows clear sequential peaks in angular velocity, and deviations (e.g., premature wrist release or late trunk rotation) can reduce clubhead speed or destabilize face angle at impact.

6. what role does trunk rotation and deceleration play?

Answer: Trunk rotation generates large angular velocities and rotational power that are transmitted to the upper limbs and club. Effective deceleration of the trunk through eccentric control of core musculature ensures controlled energy transfer and stabilizes the upper body so that distal segments can fine‑tune clubhead orientation. Insufficient trunk rotation or uncontrolled deceleration can force compensatory distal movements that degrade accuracy.

7. How do arm extension and wrist mechanics influence launch and dispersion?

Answer: Sustained lead arm extension maintains a consistent swing radius and helps produce predictable clubhead path and angle of attack. Wrist angles and pronation/supination near and after impact adjust clubface orientation; appropriate pronation at follow‑through can be associated with square clubface at impact and predictable spin.Conversely, early collapsing of the lead wrist or excessive late forearm rotation can close or open the face, increasing dispersion.

8. What measurement technologies are recommended for follow‑through analysis?

Answer: Validated tools include optical motion‑capture systems for high‑resolution kinematics, force plates for GRF and center‑of‑pressure, surface electromyography (EMG) for muscle activation patterns, high‑speed cameras for clubhead/face visualization, and inertial measurement units (IMUs) for field assessments. A multimodal approach provides the most complete picture of kinematics, kinetics, and neuromuscular control.

9. What practical training recommendations arise from biomechanical findings?

Answer: Recommendations include:

– Drill proximal‑to‑distal sequencing using progressive segmental timing drills (hip rotation precedes trunk, then shoulders, then arms).

– Strength and power training emphasizing rotational core strength,hip drive,and eccentric control of trunk muscles.

– Mobility work for thoracic rotation and lead shoulder extension to allow appropriate follow‑through positions.

– Wrist and forearm drills to train controlled pronation and extension through impact.

– Incorporation of feedback tools (video, motion sensors) to monitor clubface orientation and segmental timing.Adaptation of drills to the golfer’s skill level and anthropometrics is essential.

10. How should coaches individualize follow‑through instruction?

Answer: Coaches should assess a golfer’s anthropometry, flexibility, strength, and typical kinematic patterns. Use objective measurements where possible (video, sensors) to identify whether follow‑through issues stem from proximal deficiencies (e.g., limited hip rotation), neuromuscular timing errors, or compensatory habits. Interventions should prioritize correcting the source (e.g., mobility, strength, sequencing) rather than only altering visual positions.

11. What are common injury risks related to follow‑through mechanics and how can they be mitigated?

Answer: Poor follow‑through mechanics can increase loading on the lumbar spine, shoulders, elbows, and wrists (e.g., abrupt deceleration or excessive rotational shear). mitigation strategies include improving trunk eccentric control, optimizing lower‑body contribution to reduce torsional load on the spine, progressive conditioning for shoulder and wrist stability, and correcting swing faults that produce impulsive joint loads.

12. How does skill level influence biomechanical targets for follow‑through?

Answer: Elite golfers typically demonstrate more consistent proximal‑to‑distal sequencing, higher segmental angular velocities with controlled deceleration, and narrower variability in clubface orientation. Recreational golfers may benefit most from basic sequencing drills, mobility, and strength work. Biomechanical targets should be realistic and progressive, emphasizing repeatability rather than maximal velocity for developing players.

13. What limitations exist in current biomechanical understanding and research?

Answer: Limitations include inter‑individual variability in morphology and technique, ecological validity of laboratory settings (influence of fatigue, course conditions), and limited longitudinal intervention studies linking specific biomechanical changes to long‑term performance improvements. Measurement error and the complexity of multi‑joint coordination also challenge causal inference between particular follow‑through features and shot outcomes.

14. What future research directions are recommended?

answer: Future work should focus on:

– Longitudinal intervention trials that test targeted training on sequencing, strength, and mobility and their effects on accuracy and injury incidence.

– Field‑based validation of wearable sensors to monitor follow‑through in real practice and competition.

– Modeling studies that quantify how small changes in follow‑through kinematics alter launch dynamics and dispersion.

– inquiry of individual predictors (anthropometry,neuromuscular profile) that determine optimal individualized follow‑through strategies.

15. How can practitioners integrate biomechanical assessment into routine coaching?

Answer: Practitioners should adopt a tiered approach: screen with simple video and functional movement tests; use portable IMUs or slow‑motion video for routine monitoring; refer to laboratory assessments (3D motion capture, force plates, EMG) for complex cases or performance optimization. Combine objective data with on‑course performance metrics and athlete‑reported outcomes to drive evidence‑based, individualized coaching plans.

References and further reading:

– General biomechanics definitions and principles: Britannica ([1]), Physiopedia ([4]).

– Past and methodological context for biomechanics research: PMC review ([3]).

this investigation elucidates the biomechanical determinants of an effective golf follow-through, demonstrating that coordinated trunk rotation, full arm extension and timely wrist pronation materially contribute to increases in clubhead speed, optimal ball launch conditions, and improved shot consistency. These findings reinforce basic principles from the broader biomechanics literature, which treat human movement as an integrated, multi‑segment system whose performance emerges from coordinated intersegmental kinetics and kinematics.

Practically, the results suggest that coaching and training programs should emphasize drills and exercises that promote controlled rotational power of the torso, maintain an extended and stable lead arm through impact, and refine the timing of distal forearm and wrist motion. Conditioning interventions that enhance rotational strength, core stability, and proprioceptive control are likely to translate into measurable improvements in follow‑through mechanics and, by extension, performance outcomes on the course.

Methodologically, the study highlights the value of high‑speed video and motion‑capture technologies for quantifying subtle temporal and spatial features of the follow‑through that are not readily apparent through conventional observation. At the same time, practitioners should interpret these kinematic markers in the context of individual variability-anthropometry, skill level, and injury history can modulate the optimal expression of the follow‑through for any given golfer.

Future research should pursue longitudinal and intervention studies to test causal relationships between targeted biomechanical training and on‑course performance, and should integrate kinetic and muscle‑activation (EMG) data to more fully characterize the neuromuscular strategies underpinning effective follow‑throughs. Cross‑disciplinary collaboration, drawing on advances in biomechanics, motor control and sports science, will accelerate the translation of laboratory insights into robust, evidence‑based coaching practices.

In closing, a biomechanically informed approach to the golf follow‑through offers a principled pathway to enhance performance while managing injury risk. by combining precise measurement, individualized assessment, and targeted training, players and coaches can optimize follow‑through mechanics in ways that are both technically sound and practically meaningful.

Biomechanics of an Effective Golf Follow-Through

Understanding the biomechanics behind a high-quality golf follow-through turns random good shots into repeatable, accurate performance. The follow-through is not just a finishing pose - it’s the visible outcome of proper sequencing,force submission,and controlled deceleration that determine launch conditions (launch angle,spin rate,clubhead speed) and long-term shot repeatability.

Why the Follow-Through Matters for Your Golf Swing

- Launch conditions – The follow-through reflects what happened at impact. A consistent follow-through usually means consistent launch angle and spin.

- Kinematic sequencing - Proper timing of pelvis, torso, arms and hands through the finish preserves clubhead speed and target line.

- Injury prevention – Controlled deceleration reduces stress on the wrists,elbows and lower back.

- Balance and repeatability – Finishing in balance reinforces the correct swing path and weight shift.

Key biomechanical Principles of an effective Follow-through

1. Kinematic Sequence (Rotational Sequencing)

The kinematic sequence describes the proximal-to-distal order of motion: pelvis → torso → lead arm → club. An efficient sequence spaces energy transfer so the clubhead reaches maximum speed at impact.A correct follow-through will show:

- Hips rotated well toward the target (lead hip open relative to trail hip).

- Torso rotation following hips; shoulders turn through with chest pointing past the ball line.

- Arms and hands extending naturally; club continuing on the intended swing plane.

2. Ground Reaction Forces and Weight Transfer

Ground reaction forces (GRF) provide the base for powerful rotation. During a proper follow-through you shoudl see:

- Weight shifted to the lead foot by impact and maintained into the finish.

- Trail foot often rises (heel up) as weight transfers and hips rotate.

- Stable base – a balanced finish indicates efficient force transmission from legs to club.

3. Controlled Deceleration

The body must decelerate safely after impact while allowing the club to release. Deceleration is an active, coordinated process – not a sudden halt. Good deceleration characteristics:

- Gradual reduction of arm speed managed by larger muscle groups (core and lats) rather of wrists alone.

- minimal abrupt braking at the wrists - prevents slices or hooks caused by late manipulation.

4. Postural Integrity and Spine Angle

Maintaining a stable spine angle through impact and into the follow-through helps preserve the swing plane. Look for:

- Consistent spine tilt through the swing; follow-through doesn’t require collapsing upright instantly.

- Balanced head position – not over-rotated, allowing the eyes to track the ball flight while the body turns.

Visual and Measurable Follow-Through Checkpoints

| Checkpoint | What to Observe | Why It Matters |

|---|---|---|

| Hip Rotation | Lead hip open toward target | Indicates proper weight transfer and power delivery |

| Shoulder Turn | Chest near or facing target | Shows torso followed hips – good sequencing |

| Arm Extension | Arms extended, club pointing up | Sign of clean impact and release |

| Balance | Hold finish >1-2 seconds | repeatable, stable mechanics |

Common Follow-through Faults and Biomechanical Causes

Overactive Hands / Early release

Cause: Late pelvic rotation or poor sequencing. Hands try to create speed and manipulate the club, leading to inconsistent face control and variable spin.

Standing Up or Swaying

Cause: Loss of posture and poor lower-body engagement. Results in inconsistent low-point control and variable launch angles.

Falling Backward or Balance Loss

Cause: Insufficient weight transfer to the lead foot. Reduces control through impact and often leads to pushed or blocked shots.

Practical Drills to Improve Follow-Through Mechanics

- Step-Through Drill: Start with a normal address, swing and step the trail foot forward through to the lead side on the finish. Emphasizes aggressive weight transfer and hip lead.

- Wall Finish Drill: Stand 1-2 feet from a wall on your target side, swing and finish without touching the wall. Promotes chest and arm turn without over-rotating.

- Slow-Motion Kinematic Sequence: Perform slow swings focusing on pelvis → torso → arms → club. Use a mirror or video to check the correct order.

- Towel Under Arm Drill: Keep a small towel under your armpit through the swing to maintain connection between body and arms,producing a unified follow-through.

- Balance Hold: Hit half shots and hold a balanced finish for 2-3 seconds each time. This reinforces repeatability and reduces excessive hand action.

Training & Conditioning for a Better Follow-Through

Biomechanics is movement plus strength. Train these physical attributes to create a reliable finish:

- Rotational power: Russian twists, medicine ball throws, and cable chops.

- Hip mobility: Dynamic hip openers,lunges,and thoracic rotation stretches.

- Leg strength and balance: Single-leg deadlifts, squats, and stability work to manage GRF.

- Core endurance: Planks and anti-rotation exercises to control deceleration.

How Follow-Through Affects Launch conditions and Shot Shape

A clean,biomechanically sound follow-through is tightly linked to:

- Launch angle: Proper shaft lean at impact and follow-through verticality correlate to the intended launch.

- Spin rate: Unneeded manipulation in the follow-through often indicates face rotation near impact – a key spin driver.

- Clubhead speed: efficient sequencing that remains visible in the finish correlates to higher usable clubhead speed at impact.

- Shot shape consistency: Balanced finishes reflect consistent swing path and face angle through impact – the two primary determinants of ball direction.

Simple On-course Cues to Reinforce Biomechanics

- “Finish tall and balanced” – checks posture and balance.

- “Turn your chest past the target” – encourages torso follow-through after hips rotate.

- “lead heel down (or trail heel up)” – confirms weight shift and hip turn.

- “Let the arms extend” – prevents wrist-centric releases that cause spin and path errors.

Case Study: From slice to Hybrid Confidence (Illustrative)

A mid-handicap player struggled with a consistent slice. Video analysis showed insufficient hip rotation and early hand release. The coach implemented:

- Rotation drills (slow kinematic sequence) – to correct pelvis-to-torso timing.

- Towel under arm drill - to preserve connection through impact.

- Balance hold practice – to cement weight transfer into the lead foot.

Over six weeks the player reported fewer slices and better carry distance; launch monitor data showed a reduced side spin and slightly higher peak clubhead speed – improvements consistent with a cleaner follow-through.

Quick follow-Through Checklist for Practice Sessions

- Can you hold your finish for at least 1-2 seconds?

- Is your lead hip and chest pointing past the ball line?

- Has most of your weight shifted to the lead foot?

- Are your hands relaxed with the club pointing up or slightly across the target line?

- Does the movement feel like a continuation of the rotation rather than a forced stop?

Further Reading & Resources

- Stanford Biomechanics – foundational biomechanics concepts.

- Biomechanics – Wikipedia – overview of the field and principles.

- physio-pedia: Biomechanics – applications to movement and injury prevention.