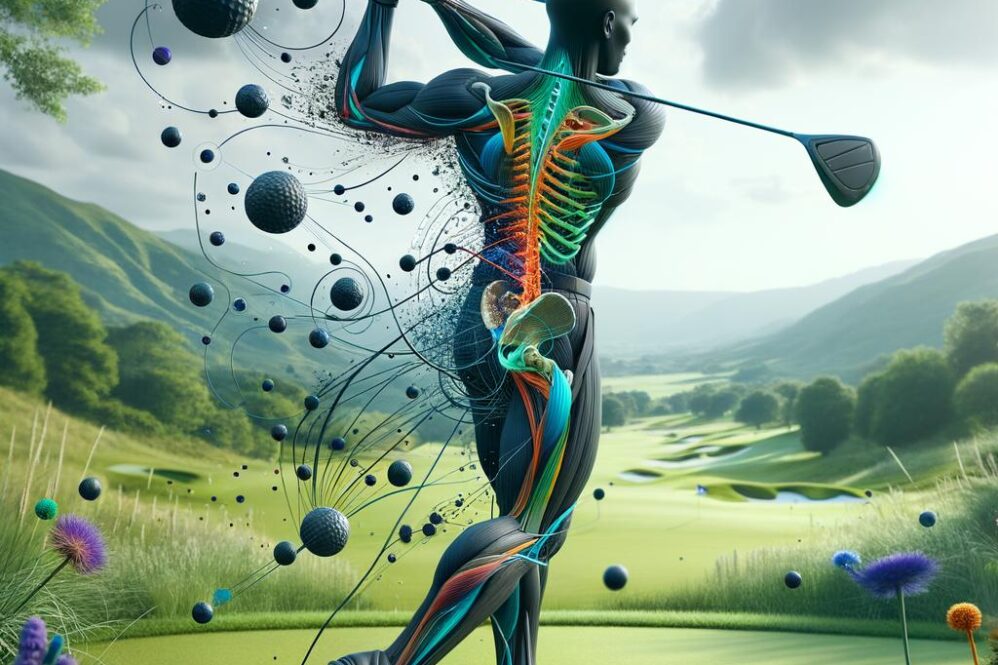

The follow-through phase of the golf swing constitutes a critical period in which kinematic sequencing, kinetic transfer, and neuromuscular control jointly determine ball trajectory, shot repeatability, and the distribution of mechanical loads across the musculoskeletal system. Framed within the discipline of biomechanics-the application of mechanical principles to living movement-analysis of the follow-through elucidates how joint timing, angular velocities, and force attenuation influence both performance outcomes and injury risk.

This article synthesizes empirical and theoretical perspectives on proximal-to-distal joint sequencing, momentum transfer through the kinetic chain, and controlled deceleration strategies that underpin follow-through mastery. Emphasis is placed on translating biomechanical descriptors (e.g., segmental angular momentum, ground-reaction forces, eccentric muscle actions) into practical assessment criteria and training interventions for players and coaches. By linking mechanistic insight to applied technique and conditioning, the discussion aims to enhance shot accuracy and consistency while minimizing cumulative tissue stress.

Kinematic Chain Dynamics in the Follow Through and Implications for Shot Accuracy and Precision

The follow-through phase represents the terminal expression of the proximal-to-distal sequencing that began in the lower body and culminated at ball contact. In biomechanical terms, it is not merely a passive deceleration but an active continuation of the kinematic chain where residual angular momentum is redistributed across segments. Proper sequencing during this phase ensures that clubhead orientation at impact is the product of controlled energy transfer rather than corrective compensation-thereby reducing late-phase perturbations that manifest as lateral dispersion.key control points are the timing of trunk deceleration, coordinated arm extension, and the managed release of wrist angular velocity; together thes determine the final vector of clubhead travel and face alignment.

Mechanistically, the kinematic chain during the follow-through can be modeled as a series of linked rigid segments exchanging angular momentum and work via torque impulses and muscle-tendon interactions. eccentric braking in axial trunk musculature and graded eccentric-to-concentric transitions in the shoulder girdle absorb and redirect kinetic energy, preserving clubhead speed while minimizing unwanted rotations of the forearm and hand. Quantitatively, simplified partitioning of relative contributions illustrates the principle of proximal dominance in energy transfer:

| Segment | Illustrative Contribution |

|---|---|

| Trunk rotation | ~40-50% |

| Arms / shoulder complex | ~30-35% |

| Wrist / hand release | ~15-25% |

From a variability and precision standpoint, late-chain noise-small timing or amplitude errors in the terminal segments-has an amplified effect on clubface angle and launch vector as of the lever lengths and angular velocity magnification.Monitoring and calibrating the following kinematic variables is therefore essential for precision:

- Trunk rotational velocity and deceleration profile

- Arm extension angle at post-impact

- wrist pronation/supination timing

- Pelvic alignment and residual rotation

Fine-tuning these variables reduces between-shot variability (precision) while preserving optimal launch conditions (accuracy).

Practically, coaching and training should emphasize targeted neuromuscular control and sensorimotor feedback during the follow-through. effective interventions include eccentric trunk strengthening, tempo drills that preserve proximal-to-distal timing, and constrained-practice tasks that isolate wrist release timing. Objective assessment with wearable IMUs or motion-capture systems can quantify sequencing metrics and identify compensatory patterns; when combined with progressive overload and proprioceptive drills, these methods foster a follow-through that reliably converts generated energy into repeatable, accurate ball flight. In sum,optimizing kinematic chain dynamics in the follow-through is both a mechanical imperative and a trainable skill for improving shot accuracy and precision.

ground Reaction Forces and Weight Transfer Strategies to Stabilize Post Impact Ball Trajectory

Ground reaction forces (GRFs) are primary determinants of post‑impact stability: they transmit the sum of segmental accelerations and body mass to the club-ball system through the feet and substrate. Conceptually this leverages the literal definition of “ground” as the earth’s surface (see Merriam‑Webster),which underscores that the force vector originates at the interface between foot and turf. Precise timing and magnitude of the vertical and horizontal GRF components immediately before and after impact condition the clubhead’s effective loft and face orientation, thereby reducing angular and lateral dispersion of launch vectors.

Optimizing weight transfer requires coordinated segmental control to shape GRF direction. Key biomechanical priorities include a controlled lateral shift to the lead limb, progressive vertical force absorption in the trail limb, and maintenance of a stable center‑of‑pressure under the lead foot to resist unwanted transverse rotation. Practical cues that translate these priorities into motor patterns include:

- Lead‑leg brace: feel a firm, but not locked, support at impact to anchor the distal contact point;

- Pelvic deceleration: allow the pelvis to decelerate smoothly while the thorax continues rotation to preserve clubface alignment;

- Active forefoot loading: maintain forefoot pressure through follow‑through to sustain launch angle control.

From an assessment standpoint, the most informative metrics are the magnitude and vector orientation of the vertical GRF, the anterior‑posterior shear, and the trajectory of the center‑of‑pressure (CoP) during the 100 ms window surrounding impact. force‑plate analyses reveal that smaller variability in CoP path and earlier attainment of a stable lead‑foot vertical GRF correlate with reduced lateral dispersion of shot outcomes. when reporting results, present both peak values and time‑normalized curves (e.g., % of stance) to capture the dynamic interplay between weight transfer and rotational kinematics.

Translating laboratory findings to coaching practice involves progressive, load‑specific drills that embed desirable GRF patterns into the neuromuscular system. Effective interventions include tempo‑controlled half‑swings emphasizing weight transfer timing, single‑leg balance progressions to enhance CoP consistency, and resisted rotations to build eccentric control of the pelvis. Clinicians should monitor for compensations-excessive knee valgus, over‑rigid ankle fixation, or premature trunk blocking-that can create aberrant GRF vectors and compromise ball trajectory. ultimately, systematic modulation of ground reaction forces and deliberate weight transfer strategies yield more reproducible launch conditions and tighter shot dispersion.

Torso Rotation and Shoulder Mechanics for Consistent Clubface Orientation in the Follow Through

The torso plays a central role in follow-through mechanics as it functions as the primary kinematic link between the lower extremities and the upper limb system. Anatomically, the torso (trunk) constitutes the central body segment from which shoulder girdle and arms emerge; its rotational inertia and timing govern the angular momentum transmitted to the club. From a biomechanical perspective, controlled and continuous trunk rotation through the follow-through minimizes abrupt torque reversals at the shoulder that or else produce unwanted clubface rotation at impact, thereby stabilizing post-impact clubface orientation and reducing lateral dispersion.

Shoulder mechanics must be considered as a coordinated system comprising scapular protraction/retraction, glenohumeral rotation, and the relative motion of the clavicle and thorax. Efficient follow-through is characterized by an ipsilateral shoulder that continues to rotate around the thorax in concert with trunk rotation while maintaining appropriate humeral plane alignment; this coupling preserves the clubhead’s rotational axis and mitigates face-open or face-closed tendencies. In particular, controlled eccentric activity of the posterior shoulder musculature and timed scapular upward rotation are essential to decelerate the distal segments without inducing compensatory wrist or forearm motions that alter face angle.

- Trunk rotation velocity: determines residual angular momentum applied to the club during follow-through.

- Scapulothoracic stability: maintains shoulder plane and prevents face deviation.

- Glenohumeral deceleration: controls distal segment lag and face orientation.

- Timing of arm extension: synchronizes with torso rotation to preserve loft and face alignment.

| Primary Structure | Principal Action in Follow-Through | Effect on Clubface |

|---|---|---|

| Obliques & Erector Spinae | Sustained trunk rotation and deceleration | Reduces unwanted face rotation |

| Scapular stabilizers (serratus, rhomboids) | Maintain shoulder girdle alignment | Promotes consistent loft and face angle |

| Rotator cuff | Fine control of humeral rotation and deceleration | Limits abrupt face twists |

For applied coaching and training, emphasize measurable cues that reinforce the kinetic chain sequence: smooth continuation of torso rotation after ball release, maintenance of a stable scapular platform, and deliberate humeral deceleration rather than abrupt stopping. Objective monitoring (inertial sensors on the trunk and club, high-speed video of shoulder plane) can quantify rotation velocity, scapular displacement, and arm‑shaft lag to guide progressive interventions. Implementing progressive eccentric shoulder and trunk control drills-coupled with feedback on clubface orientation-produces repeatable biomechanical patterns that enhance consistency in clubface orientation during the critical follow-through epoch.

Wrist and Forearm Release Timing as a Determinant of Ball Direction,Spin,and Dispersion

Functional anatomy underpins release behavior: the wrist is a condyloid radiocarpal articulation that functions as a multi‑axial pivot between forearm and hand,while forearm pronation/supination (radioulnar joints) govern clubface rotation. The coordinated action of wrist flexors/extensors and the pronator/supinator musculature produces the final angular impulses transmitted to the clubhead. These anatomical facts explain why small temporal shifts in distal segment motion have outsized effects on impact conditions and why the wrist/forearm complex is a primary locus of control for final face orientation (see radiocarpal joint mechanics and wrist mobility characteristics in anatomical literature).

The temporal sequencing of forearm rotation and wrist unhinging determines the instantaneous clubface angle, the relative orientation of the clubhead velocity vector, and the magnitude/direction of spin. In biomechanical terms, the distal release serves three mechanical functions: (1) conversion of stored elastic energy into clubhead speed, (2) establishment of face‑to‑path relationship at impact, and (3) modulation of angular momentum about the ball contact point that governs spin axis. Consequently, inconsistent release timing yields increased lateral dispersion and variable side spin, whereas repeatable timing supports predictable launch conditions.

Observed practical patterns are consistent across experimental and coaching literature: early uncocking or “casting” dissipates energy and frequently enough produces an open face at impact (higher side‑spin and lateral misses); an appropriately timed proximal‑to‑distal release maximizes clubhead speed while allowing the hands to square the face; maintaining excessive lag until after impact can increase speed but raises the risk of abrupt face closure and hook tendencies if not controlled. Key contributors to these outcomes include:

- Wrist flexion/extension timing - affects vertical attack angle and dynamic loft.

- Forearm pronation/supination timing - directly alters face rotation and spin axis.

- Intersegmental coordination - variability here correlates with dispersion.

Table – simplified mapping of release timing to typical ball outcomes:

| Release Timing | Characteristic | Typical Ball Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| Early (casting) | Loss of lag, reduced elastic recoil | Lower speed, open face → slice/greater dispersion |

| On‑time (proximal→distal) | Efficient energy transfer, controlled face | Max speed with consistent launch and minimal dispersion |

| late (excess lag) | High speed potential, abrupt face change | high spin; risk of closed face → hook if over‑rotated |

Balance, Center of Mass Progression, and Postural Alignment for Repeatable Stroke Patterns

Reliable ball striking begins with a stable foundation: the feet, ankles and hips must create a predictable interaction with the ground so that rotational forces are transmitted efficiently.Empirical measures such as **ground reaction force** (GRF) distribution and center-of-pressure excursions quantify this stability; smaller excursions and a consistent pressure path correlate with more repeatable outcomes. Clinically relevant variables include base width, ankle stiffness and sagittal plane control-each modulates the ability to resist unwanted lateral sway while permitting clean transverse rotation of the pelvis and thorax.

The controlled anterior progression of the player’s center of mass is central to consistent timing and impact geometry.Effective follow-through mechanics rely on a coordinated posterior‑to‑anterior COM transfer that is synchronized with the kinematic sequence (pelvis → thorax → upper extremities → club). When COM progression is mistimed-too early lateral shift or arrested forward transfer-dispersion and loss of clubhead speed occur. maintain attention to **timing** and the magnitude of transfer rather than gross positional endpoints for reproducible strokes.

- Pressure cue: gradual shift to the lead foot with increased forefoot engagement through impact

- Spine cue: maintain neutral spine angle from takeaway through early follow-through

- Pelvic cue: controlled rotation, not excessive translation, to preserve the kinematic chain

Postural alignment organizes the kinetic chain and reduces injury risk by minimizing compensatory moments at the lumbar spine and shoulder complex. A stable postural chain-neutral spine, balanced shoulder plane relative to the pelvis, and a predictable head position-enables efficient impulse transfer and consistent clubface orientation at impact. Rehabilitation and performance programs should address the mobility-stability balance of the thoraco‑pelvic junction and scapulothoracic articulation to support repeatable mechanics and protect load‑sensitive tissues such as the lumbar facet joints and rotator cuff.

| phase | COM target | Postural cue |

|---|---|---|

| Address | even (≈50/50) | Neutral spine, balanced feet |

| Impact | forward bias (≈60-70% on lead) | Forefoot engagement, pelvis beginning rotation |

| finish | Predominantly lead (≈80-95%) | Chest to target, controlled deceleration |

Neuromuscular Coordination, Proprioception, and Motor Learning Methods to Reinforce Follow through Consistency

Effective control of the terminal phase of the swing depends on the integrated function of sensory receptors, spinal circuits, and supraspinal motor planning centers. The peripheral proprioceptive apparatus (muscle spindles, Golgi tendon organs, and joint mechanoreceptors) provides continuous afferent input that refines timing and amplitude of muscle activations during the deceleration and extension phases. When coupled with anticipatory trunk and scapulothoracic stabilization, this afferent-efferent loop permits the athlete to maintain the desired clubhead path and face angle at impact. Consistency thus emerges from precise sensorimotor integration rather than from isolated muscular strength.

Motor learning principles guide how these sensorimotor processes become robust under competitive conditions. Practice schedules that emphasize variable practice (alternating targets, lies, and perturbations), use of externally focused cues, and systematic reduction of augmented feedback (fading frequency of instruction or video replay) enhance retention and transfer of follow-through patterns. Error-based learning (augmented by augmented feedback early, then reduced) and differential learning approaches both promote adaptable movement solutions, while deliberate, repeated exposure to target conditions consolidates feedforward predictions necessary for accurate launch angle and clubhead speed.

Applied interventions should be multimodal and progressive.Implement training blocks that combine balance and proprioceptive drills with task-specific motor practice:

- Perturbation drills: light platform tilts or partner nudges during half-swings to reinforce dynamic postural control.

- Sensory-reintegration exercises: eyes-closed slow swings and variable-terrain stance work to heighten proprioceptive reliance.

- Augmented-feedback tools: short video clips, auditory tempo cues, and simple wearable haptics to reinforce correct timing without creating dependency.

- Transfer sessions: randomized practice with differing targets and club lengths to build adaptable follow-through schemas.

These elements prioritize functional stability of the trunk and distal sequencing (arm extension, wrist pronation) essential for reproducible impact geometry.

Progression and monitoring should be objective and incremental. Use short microcycles with quantifiable targets for movement variability and outcome consistency; the table below gives a concise example protocol for a weekly microcycle. individuals with diagnosed neuromuscular conditions or unexplained coordination deficits should consult a neuromuscular specialist or rehabilitation professional before commencing high-velocity training (see MedlinePlus and neuromuscular medicine resources for background facts). Metrics for evaluation include reduction in lateral dispersion, standard deviation of peak clubhead speed, and kinematic repeatability of trunk rotation at impact.

| Day | Drill | Primary Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Closed‑eye slow swings | Proprioceptive awareness |

| 3 | Perturbation half‑swings | Postural robustness |

| 5 | Randomized target full swings | Transfer & variability |

| 7 | Feedback‑reduced caps | Retention |

Practical Assessment Protocols and Training Drills with Objective Feedback Metrics for Follow Through Mastery

Assessment begins with a standardized protocol that isolates follow‑through mechanics while controlling ball flight variables. After a dynamic warm‑up, subjects perform a sequence of 10 calibrated swings at submaximal and maximal effort while synchronized measurement systems record kinematics (3D motion capture or inertial measurement units), kinetics (force plates or pressure insoles), and club telemetry. Key objective metrics to extract include:

- Trunk rotation at 0.1s post‑impact – degrees

- Arm extension ratio – elbow angle normalized to body height

- Wrist pronation velocity – deg/s in the first 150 ms after impact

- Clubface-to-path angle at follow‑through

- Clubhead speed maintenance – speed decay rate during follow‑through

These metrics provide reproducible, practical (applied rather than purely theoretical) indices of follow‑through quality and are selected for repeatability and direct relation to ball outcome variables.

Training drills are designed to target the kinematic linkages identified by assessment and to provide immediate, objective feedback. Recommended drills include:

- Rotational Pause Drill – pause at 30° post‑impact to train controlled trunk dissipation (feedback: inertial sensor angle threshold).

- Extended Arm Path Drill – swing with a 50 cm alignment rod along the lead forearm to reinforce full arm extension (feedback: smartphone video overlay or IMU elbow angle).

- Pronator Snap drill – short swings focusing on a rapid pronation cue with a wearable gyroscope to quantify pronation peak.

Each drill pairs a concise performance target with a measurement modality (e.g., IMU, radar, or high‑speed camera) so that improvements are tracked objectively rather than by subjective feel alone.

Progressive assessment and decision rules should be formalized in a simple scoring matrix used by coaches and practitioners. A compact example is shown below; thresholds are conservative and intended for intermediate players, but the structure supports sport‑specific scaling. The table uses WordPress table styling for easy integration into coaching pages.

| Metric | Target Zone | Tool | Action if outside |

|---|---|---|---|

| Trunk rotation (° at 0.1s) | 25-35° | IMU / Motion capture | rotational stability drills |

| Arm extension (elbow°) | 160-175° | Video / IMU | extension bias swings |

| Pronation velocity (deg/s) | 600-900 deg/s | Gyroscope | Pronator snap progressions |

| Clubface-to-path (°) | -2 to +2° | Launch monitor | Face control and path drills |

Accomplished coaching requires integration of objective feedback into the session flow: set baseline KPIs, apply targeted drills, and use threshold‑based progression criteria for return‑to‑play or competition readiness.Real‑time alerts (auditory tones or haptic pulses) tied to metric bands accelerate motor learning, while periodic retesting every 2-4 weeks quantifies retention. Emphasizing a practical approach-operationalizing theory into measurable,coachable targets-ensures that biomechanical insights translate into repeatable swing behavior and improved shot accuracy.

Q&A

Q1.What is meant by “biomechanics” in the context of the golf swing follow-through?

A1. Biomechanics is the scientific study of movement mechanics in living organisms, applying principles of physics and engineering to understand how muscles, bones, joints, and connective tissues produce and control motion.In the context of the golf swing follow-through, biomechanics examines the kinematics (motion trajectories, joint angles, angular velocities), kinetics (forces, torques, ground reaction forces), and neuromuscular activation patterns that occur after ball impact and that contribute to clubhead trajectory, energy transfer, and shot outcome [Verywell Fit; stanford; Nature].

Q2. Why is the follow-through phase vital for shot accuracy and performance?

A2.Although ball-ball contact occurs before the completion of the follow-through, the follow-through reflects the quality of the preceding kinematic sequence and neuromuscular coordination. Proper follow-through execution is associated with consistent clubface orientation, optimized clubhead speed decay, balanced deceleration patterns, and effective transfer of momentum through the kinetic chain. Deviations in follow-through mechanics frequently enough indicate timing errors, compensatory motions, or inadequate energy transfer that can degrade launch conditions and lateral accuracy.

Q3.Which biomechanical factors of the follow-through most strongly influence accuracy?

A3. Key follow-through factors linked to accuracy include: (1) trunk rotation continuity and timing, which stabilizes torso-to-shoulder relationships and supports consistent clubface alignment; (2) controlled arm extension and elbow mechanics, which influence release timing and dynamic shaft orientation; (3) wrist pronation/supination (release mechanics), which govern clubface rotation at and immediately after impact; (4) weight transfer and ground reaction force patterns, which affect balance and hosel/shaft loading; and (5) the overall kinematic sequence (proximal-to-distal sequencing), which preserves energy transfer and minimizes late compensations that perturb ball flight.

Q4.How are trunk rotation, arm extension, and wrist pronation each mechanistically linked to launch and accuracy?

A4. Trunk rotation: Sustained, well-timed trunk rotation through and beyond impact maintains shoulder-chest geometry and reduces undesired lateral torso sway, promoting consistent club path and face orientation. Arm extension: Adequate controlled extension of the lead arm facilitates a stable swing arc and consistent impact location on the clubface; excessive early bending or late collapsing introduces variability. Wrist pronation: The timing and rate of forearm rotation (pronation) near and after impact determine face rotation and therefore influence initial ball direction and side spin.Interaction among these three subsystems is critical-mis-timed trunk rotation can alter arm mechanics and wrist release, producing face-angle errors.Q5. What measurement and analytic methods are used to study follow-through biomechanics?

A5. Typical methods include 3D motion capture (marker-based or markerless) for joint kinematics and club trajectories; force plates for ground reaction force and center-of-pressure analysis; electromyography (EMG) to quantify muscle activation timing and intensity; high-speed video for clubface/impact inspection; instrumented clubs or launch monitors (e.g., Doppler radar) for clubhead speed, face angle, launch angle and spin; and inverse dynamics to estimate joint torques and power. Statistical and machine-learning approaches are used to relate biomechanical metrics to outcome variables (accuracy, dispersion, carry distance).Q6. What does the kinematic sequence look like for an optimal follow-through?

A6. An optimal sequence follows a proximal-to-distal cascade that extends into the follow-through: continued trunk rotation (pelvis → thorax) drives shoulder rotation,which drives elbow extension and forearm rotation,and finally hand and club release. In the follow-through this sequence should decelerate smoothly with progressive reductions in angular velocities, avoiding abrupt compensatory motions. A smooth decay in segmental angular velocities indicates efficient energy transfer and lower likelihood of late face-rotation errors.

Q7. How do ground reaction forces and weight transfer during follow-through affect shot outcomes?

A7. Ground reaction forces (GRFs) reflect how the golfer stabilizes and decelerates after impact. Effective weight transfer toward the lead leg before and through impact, followed by a controlled application of vertical and shear GRFs during the follow-through, supports balance and consistent body-center progression. Asymmetric or abrupt GRF patterns in the follow-through often indicate lateral sway or early cast, which correlate with unpredictable clubface path and increased lateral dispersion.

Q8.What muscle groups are most active during follow-through and why is their coordination critically important?

A8. Primary muscle contributors during follow-through include trunk rotators (obliques, multifidus), hip extensors and abductors for weight transfer and stabilization (gluteus maximus/medius), shoulder stabilizers and rotators (deltoids, rotator cuff), elbow extensors (triceps), and forearm pronators/supinators. Coordinated activation ensures smooth deceleration of the distal segments, prevents excessive joint loading, and preserves clubface control; asynchronous or excessive co-contraction can introduce timing errors that affect face orientation.

Q9. How do follow-through mechanics differ between novice and expert golfers?

A9. Experts typically exhibit: more consistent proximal-to-distal sequencing; smoother decay of angular velocities; more reproducible trunk rotation and center-of-mass control; reduced compensatory wrist movements; and more consistent GRF patterns. Novices often show greater variability in trunk timing, premature arm collapse or casting, inconsistent pronation timing, and larger fluctuations in balance, all of which increase shot dispersion.

Q10. What practical drills and training interventions can improve follow-through biomechanics?

A10. Evidence-based drills include:

– Slow-motion sequencing drills: execute full swings at reduced speed while focusing on continuous trunk rotation through the finish to ingrain proximal initiation.

– Pause-at-impact drills: pause briefly just after impact to sense correct extension and torso position, then resume the follow-through.

– resistance band trunk-rotation drills: reinforce coordinated hip-to-shoulder rotation and control during follow-through.

– Throwing or medicine-ball rotational throws: develop explosive proximal-to-distal sequencing and trunk power.

– Wrist-release timing drills with short swings: practice pronation timing without full-speed loads.

– Balance and single-leg stability exercises: improve GRF control and center-of-pressure management.

Progressive overload and motor learning principles (blocked to random practice, variable practice, and augmented feedback) enhance transfer to on-course performance.

Q11. what strength, mobility, and conditioning elements support an optimal follow-through?

A11. Strength: rotational power in the core and gluteal strength for hip drive; eccentric strength in the forearm and shoulder musculature to control deceleration. Mobility: thoracic rotation and hip internal/external rotation ranges are critical to allow full trunk turn without compensation. conditioning: proprioception and balance training, and plyometric rotational work (medicine-ball throws) to reinforce rapid concentric-eccentric transitions. Program design should be individualized, progressive, and sport-specific.

Q12. What are common injury risks associated with improper follow-through mechanics, and how can they be mitigated?

A12. Risks include lumbar strain from inadequate core control or abrupt trunk deceleration, lateral elbow tendinopathy from poor release timing, shoulder impingement from uncontrolled deceleration or overreaching, and wrist/hand overload from improper pronation mechanics. Mitigation strategies: correct technique through biofeedback, targeted eccentric strengthening for decelerators (rotator cuff, forearm extensors), progressive mobility work to reduce compensatory patterns, and workload management to avoid sudden increases in swing repetitions or intensity.

Q13. how should coaches and practitioners assess and provide feedback on follow-through mechanics?

A13. Use a multimodal assessment: slow-motion video and 3D capture for kinematics, force plates for GRFs where available, and launch monitor data for outcome measures. Prioritize objective, repeatable metrics (e.g., trunk rotation angle at 0.1 s post-impact, elbow angle at follow-through, face-angle variability). Provide concise, actionable feedback using cueing that emphasizes proximal initiations (e.g.,”rotate through with the chest”) and outcome-focused measures (launch angle,dispersion). Employ augmented feedback judiciously-start with more feedback during acquisition, then reduce to promote retention.

Q14.What are methodological considerations and limitations in biomechanical studies of follow-through?

A14. Common considerations include ecological validity (lab-based captures may alter natural swings), marker occlusion and soft-tissue artifact in motion capture, intersubject variability in anatomy and technique, and the difficulty of isolating cause-effect relationships from correlational data. Small sample sizes and heterogeneity in skill levels can limit generalizability. Combining lab measures with on-course or simulator data and longitudinal intervention designs strengthens inference about causality and transfer.

Q15. What are promising directions for future research?

A15. Future work should: integrate wearable sensor and markerless capture for ecologically valid longitudinal monitoring; combine neuromuscular (EMG) and metabolic measures with biomechanics to link fatigue and follow-through degradation; apply machine-learning models to predict shot outcomes from multi-sensor biomechanical signatures; evaluate individualized intervention efficacy across skill levels; and explore age- and sex-specific adaptations and injury risk profiles.

Q16. What concise practical recommendations can be drawn for golfers seeking follow-through mastery?

A16. Emphasize continuous trunk rotation through and beyond impact, maintain controlled lead-arm extension, prioritize correct timing of wrist pronation/release, train proximal-to-distal sequencing with slow and progressive drills, develop rotational strength and eccentric decelerator capacity, and use objective feedback (video, launch monitor) to monitor face-angle consistency and dispersion. Incremental,individualized training that integrates technique,conditioning,and motor learning principles will produce the most reliable improvements in accuracy.

Selected background sources

– Verywell Fit – “Understanding Biomechanics & Body Movement” (overview of biomechanics principles)

– Nature – Biomechanics research and emerging directions

- Stanford University – Biomechanics of movement educational resources

If you would like, I can: (a) convert this Q&A into a printable academic FAQ for inclusion in your article, (b) generate figure captions for common follow-through kinematic plots, or (c) produce a short practice program (4-8 weeks) tailored to skill level.

In sum, mastery of the golf swing follow-through is best understood and advanced through a biomechanical framework that foregrounds precise joint sequencing, efficient momentum transfer, and deliberate deceleration strategies. the follow-through is not an afterthought but the kinematic and kinetic continuity of the entire swing: effective energy transfer from the ground up through the pelvis, torso, shoulder, and distal segments supports shot accuracy and consistency, while controlled eccentric activity and joint coordination mitigate injurious loads (see Britannica; Verywell Fit; Fitbudd; PMC review).

Practically, this perspective directs coaches and practitioners to integrate objective biomechanical assessment, individualized motor-control and eccentric-strength training, and feedback-informed practice into instruction. Combining qualitative observation with quantitative tools (motion analysis, wearable sensors) enables targeted interventions that respect inter-individual variability in morphology and movement patterns and that balance performance goals with tissue protection.

advancing follow-through mastery will rely on continued translational research-longitudinal studies,refined modeling of segmental interactions,and real-world validation of sensor-based metrics-to refine evidence-based coaching protocols. By situating technique within a rigorous biomechanical paradigm, players and clinicians can more reliably enhance performance outcomes while reducing injury risk.

Biomechanics of Golf Swing Follow-Through Mastery

Why the Follow-Through Matters for Clubhead Speed and Shot Accuracy

The golf swing follow-through is not just a graceful ending – it is the biomechanical fingerprint of what just happened during impact. A well-executed follow-through reflects efficient energy transfer through the kinetic chain, proper trunk rotation, complete arm extension, and controlled wrist pronation.These elements influence clubhead speed, launch angle, ball spin, and ultimately shot accuracy and consistency.

Core Biomechanical Principles Behind the Follow-Through

Kinetic Chain and Sequencing

the kinetic chain describes how force and torque flow from the ground through the legs,hips,trunk,shoulders,arms,wrists,and finally the club. Good sequencing (proximal-to-distal activation) produces a high peak clubhead speed at impact and a stable, controlled follow-through. Disruptions in timing show up as compensations later in the chain and are visible in an inefficient follow-through.

Ground Reaction Forces (GRF)

Ground reaction forces begin the energy transfer.Effective weight shift and push-off from the lead leg create a stable base for trunk rotation. Measuring GRFs with force plates in research shows that stronger, timely force submission leads to higher rotational speed and a more powerful follow-through.

Angular Momentum and Trunk Rotation

Trunk rotation stores and then releases angular momentum.The follow-through is the deceleration phase for trunk rotation – controlled deceleration protects the spine and shoulder while ensuring the clubhead path remains on plane. Over- or under-rotating can lead to missed targets and variable launch angles.

Joint Mechanics: Shoulders, Elbows, Wrists

During follow-through:

- Shoulders continue rotating open to the target, aligning the chest and upper torso.

- Arms should extend naturally, indicating good lag and efficient release at impact.

- Wrist pronation/supination controls clubface orientation; controlled pronation helps square the face and reduce unwanted spin.

Key Follow-Through Components and How They Affect Accuracy

1. Trunk Rotation (Torso Rotation)

Optimal trunk rotation continues after impact, finishing with the chest towards the target. This finishes the energy transfer and helps provide consistent clubhead speed and launch direction. Under-rotation frequently enough causes fade or pull patterns depending on face angle; over-rotation can create slices or timing issues.

2.Arm Extension and Release

Full, relaxed arm extension through impact results in a longer lever and increased clubhead speed. The follow-through should show the arms extending forward and slightly upward.Early collapse or lack of extension indicates early release, reducing power and increasing shot dispersion.

3. Wrist Pronation and clubface Control

At and after impact, controlled wrist pronation helps square the clubface and manage spin. Watch for abrupt or excessive cupping/uncupping of the wrist in the follow-through – this frequently enough signals inconsistent face control at impact.

4. Lower Body Stability and Weight Transfer

Effective weight shift to the lead leg and stabilization of the trail leg create a steady base for the upper body’s rotation. In the follow-through, most of the weight should be on the lead foot with the trail foot up on the toe or slightly off the ground for balance and power finish.

Common Follow-Through Faults and Biomechanical Fixes

- Early Release (Casting): Arms collapse before impact. Fix: Drill lag-maintenance swings and strengthen forearms/rotator cuff. Practice impact bag or half swings focusing on retaining wrist angle until just after impact.

- Incomplete Rotation / Hanging Back: Chest remains closed to the target and weight stays on the trail leg. Fix: step-through drill and medicine ball rotational throws to train weight shift and hip rotation.

- Over-Rotation / Loss of Control: Hips and shoulders spin past the target too aggressively, creating inconsistent face angles. Fix: Tempo drills and controlled deceleration exercises to rebuild coordinated deceleration of trunk rotation.

- Excessive Wrist Flip: Wild wrist movement in follow-through causing spin and dispersion. Fix: Wrist-strengthening, slow-motion impact-focused swings, and using impact tape to monitor face orientation.

Training Drills to Improve Follow-Through mechanics (Golf Swing)

Below are coach-tested drills that focus on specific biomechanical elements of the follow-through. Repeat each drill mindfully and progress gradually.

Drill List

- Step-Through Drill: Begin with a normal swing, then step the trail foot forward after impact to encourage weight transfer and trunk rotation.

- Medicine Ball Rotational Throws: Stand sideways, rotate through the hips and torso and toss a med ball to a partner or wall to train explosive rotational power and follow-through finish.

- Impact Bag or Towel Drill: Strike an impact bag or fold a towel under the lead armpit to practice extension and proper release at impact and into follow-through.

- Slow-Motion 3/4 Swings: Perform slow swings focusing on sequencing - legs, hips, trunk, arms – and hold the finish for a 3-count to ingrain a stable follow-through.

- Club-in-One-Hand Finish: Swing with the lead hand only to emphasize extension and pronation during the follow-through.Start with short swings and build to full swings.

Simple WordPress-Styled Training table

| Drill | Focus | Reps/Sets |

|---|---|---|

| Step-Through | Weight transfer & trunk rotation | 10 reps × 3 sets |

| Med Ball Rotations | Explosive rotation | 8 throws × 3 sets |

| Impact bag | Arm extension & release | 12 reps × 2 sets |

Programming Strength, Mobility, and motor Control for Follow-Through Mastery

Developing a reliable follow-through requires three pillars: strength, mobility, and motor control.

- Strength: Focus on rotational strength (Russian twists, cable woodchops), single-leg stability (lunges, single-leg Romanian deadlifts), and posterior chain (deadlifts, hip thrusts) – all improve force transfer during the swing.

- Mobility: Maintain thoracic spine rotation, hip internal/external rotation, and shoulder range of motion. Tightness in the hips or mid-back limits rotation and results in compensatory arm actions during follow-through.

- Motor Control: use slow-motion swings, tempo training, and feedback (video or coach) to engrain desirable movement patterns and sequencing.

Measuring Progress: Metrics That Matter

To evaluate follow-through improvements, monitor:

- Clubhead speed (radar/golf launch monitor)

- Launch angle and spin rate (launch monitor)

- Flight dispersion and shot grouping (on-range targets)

- Post-swing body position – chest facing target, weight on lead foot, trail foot up on toe

Short case Study: From Slice to consistent Fade – A Hypothetical Example

Client: Amateur golfer, mid-handicap, noted an outside-in swing path and an exaggerated wrist flip in follow-through causing a slice.

Assessment & Intervention:

- Video analysis revealed under-rotation of the trunk and early wrist release.

- Program (8 weeks): Med ball rotations, impact bag practice, step-through drill, thoracic mobility, and tempo training.

- Results: Clubhead speed increased by ~3-5 mph, dispersion reduced by 20-30%, and launch monitor showed more neutral face angle at impact with slightly lower spin.

Key takeaway: Targeted biomechanical drills that address sequencing and extension frequently enough translate quickly to measurable improvements in accuracy and consistency.

How Coaches and Technology Help Build a Better Follow-Through

Modern coaching uses video, motion-capture, radar-based launch monitors, and force plates to quantify where breakdowns occur. A coach can correlate kinematic sequence data with on-ball outcomes (launch angle, spin, dispersion) and prescribe precise drills targeting trunk rotation, arm extension, and wrist pronation.

Resources for deeper learning include biomechanical overviews from industry and academic sources (see Britannica on biomechanics and university biomechanics departments for applied research).

Practical Weekly Plan (Sample) for Follow-Through Advancement

Follow this 3-day-per-week template, combined with on-course practice and one recovery day.

- Day 1 – Strength & Mobility: Posterior chain, single-leg work, thoracic rotations (45-60 minutes).

- Day 2 – Technique & Motor Control: range session with slow-motion swings, step-through drill, impact bag, and 30 tracked full swings on launch monitor (60 minutes).

- Day 3 – Power & Tempo: Med-ball throws, tempo ladder swings, and short-game follow-through control (45 minutes).

SEO Tips for Coaches Writing About Follow-Through

- Include long-tail keywords naturally: “golf swing follow-through drills,” “follow-through biomechanics,” “improve clubhead speed follow-through.”

- Use header tags (H2/H3) for each subtopic and include related keywords in them.

- Provide measurable outcomes and real drill examples – searchers look for actionable guidance, not just theory.

- use images and short video snippets demonstrating drills – multimedia increases engagement and dwell time.