The golf swing is a complex, coordinated motor task that integrates multi‑segmental kinematics, force generation, and neuromuscular control to produce precise clubhead trajectories and repeatable ball outcomes. Understanding the biomechanical foundations of the swing is essential for coaches, clinicians, and researchers who seek to optimize performance, individualize instruction, and reduce the incidence of musculoskeletal injury. By translating principles from biomechanics-the submission of mechanics to biological systems-into practical diagnostics and interventions, practitioners can move beyond anecdote and tradition toward evidence‑based technique refinement.

This article synthesizes current knowledge of golf‑swing biomechanics across three interrelated domains. Kinematics describes the spatial and temporal characteristics of segmental motion (e.g., pelvis and thorax rotation, limb angular velocities, and clubhead path), highlighting how timing and sequencing (the “kinematic sequence”) underpin power transfer. Kinetics examines the forces and moments that produce those motions,including ground reaction forces,joint moments,and torque generation about the spine and hips. Neuromuscular control addresses the sensorimotor strategies-muscle activation patterns, anticipatory postural adjustments, and feedback mechanisms-that coordinate motion and adapt technique to differing task constraints and fatigue states.

The practical objective of this review is twofold: first, to articulate core biomechanical principles that reliably explain performance variance and injury mechanisms; second, to translate those principles into actionable guidance for assessment, training, and rehabilitation. we will consider measurement methods (motion capture, force platforms, inertial sensors, electromyography), summarize empirical findings linking biomechanical markers to ball speed, accuracy, and common injuries (lumbar spine, shoulder, elbow), and evaluate intervention strategies ranging from technical cueing to strength‑and‑conditioning prescriptions.

Framing the discussion within an interdisciplinary, evidence‑based paradigm, the article concludes with guidelines for implementing biomechanically informed practise in coaching and clinical settings and identifies key gaps for future research. By bridging theory and application, this synthesis aims to equip stakeholders with a principled foundation for improving performance while safeguarding athlete health.

Conceptual framework and scope for biomechanical analysis of the golf swing

A rigorous biomechanical approach frames the golf swing as a coordinated, multi‑scale motor task in which **kinematics**, **kinetics**, and **neuromuscular control** interact to produce ball flight while exposing tissues to mechanical load. Analysis thus must span from whole‑body movement patterns (segmental sequencing, center‑of‑mass trajectory) to joint‑level loading (moments, impulses) and muscle activation timing. Framing the investigation around explicit performance and health objectives clarifies which variables are prioritized for measurement, interpretation, and intervention.

Methodological scope should be explicit and justified: which instruments, what sampling rates, and which outcome metrics are chosen determine the validity of inferences. Commonly used tools include:

- 3D motion capture for segment orientations and angular velocities;

- force platforms to resolve ground reaction forces and moments;

- surface and intramuscular EMG to quantify timing and amplitude of muscle activity;

- inertial measurement units (IMUs) for on‑course and ecological data collection.

The conceptual model linking measurements must account for control strategies and mechanical constraints.A **proximal‑to‑distal sequencing** framework explains how intersegmental torques and intermuscular coordination generate clubhead speed, while a **constraints‑based** perspective (task, organism, habitat) helps interpret variability and adaptation. Analytical techniques-inverse dynamics, time‑frequency EMG analysis, and principal component decomposition-translate raw signals into interpretable descriptors of coordination and load distribution.

Scope also defines application domains and stakeholder needs: coaching,equipment design,clinical rehabilitation,and injury surveillance demand different granularity and reporting.The simple reference table below summarizes typical domain-metric pairings used to operationalize the scope for multidisciplinary teams.

| Domain | Representative metric |

|---|---|

| Performance | Peak clubhead speed |

| Injury risk | Peak lumbar extension moment |

| Motor control | EMG onset sequencing |

Translationally,the framework prioritizes **standardization**,**ecological validity**,and **individualization**: standard protocols enable comparability,field‑based measures improve relevance to play,and subject‑specific biomechanical models support tailored interventions. Future work should integrate longitudinal monitoring, probabilistic injury models, and ethical data governance to ensure that biomechanical insights are both scientifically robust and practically usable by coaches, clinicians, and equipment engineers.

Kinematic sequencing and segmental coordination: optimizing timing and angular velocities for power and accuracy

Efficient transfer of mechanical energy in the golf swing depends on a reproducible proximal-to-distal kinematic sequence that maximizes power while preserving control. In biomechanical terms, this sequence typically begins with the pelvis initiating rotation, followed by the thorax/torso, then the upper limbs, and finally the club. The temporal staggering of peak angular velocities across these segments-frequently enough referred to as the kinematic sequence-creates intersegmental torques and inertial interactions that amplify clubhead speed. Maintaining appropriate intersegmental separations (e.g., pelvis-torso separation or “X‑factor”) and minimizing early release of distal segments are foundational to both performance and load management.

Peak angular velocity patterns are as vital as their ordering. Empirical analyses indicate that maximal pelvis rotation velocity should precede maximal torso velocity, which in turn precedes peak hand and clubhead velocities by intervals on the order of tens of milliseconds. Optimal sequencing produces a smooth cascade of accelerations so that the clubhead achieves its peak velocity proximate to ball impact. Key mechanical descriptors to monitor include: peak angular velocity magnitudes, time-to-peak for each segment, and relative timing offsets. These metrics, combined with clubhead speed and launch parameters, provide an objective basis for assessing the efficacy of a golfer’s sequence.

Consistency in segmental coordination underpins accuracy; excessive variability in proximal timing increases dispersion of launch vectors. Conversely, small, controlled variability at the most distal segments can be tolerated without meaningful accuracy loss and sometimes contributes to adaptive control. Practical markers to prioritize in training are:

- Consistent temporal order (pelvis → torso → arms → club)

- Controlled separation between pelvis and torso to create elastic recoil

- Minimized early club release to preserve distal whip effect

- Stable deceleration of lead arm to refine impact alignment

Targeted interventions accelerate learning of the optimal sequence and provide measurable feedback. Common coaching drills and monitoring tools include high‑speed video,inertial measurement units (imus),and force-plate analysis to quantify timing and ground-reaction contributions. The table below summarizes practical drills, concise target cues, and primary benefits for sequence optimization.

| Drill | Target cue | Primary benefit |

|---|---|---|

| Step-through drill | Initiate with pelvis rotation | Promotes pelvis-first timing |

| Pause-at-top | Delay torso rotation 0.25-0.5 s | Enhances separation and sequence control |

| Lead-arm only | Keep trail arm passive | Improves distal timing and clubface control |

Optimization must balance performance gains with injury prevention. Faulty sequencing-such as early torso rotation without adequate pelvic drive or excessive lateral bending-elevates shear and torsional loads on the lumbar spine and shoulder complex. Conditioning strategies to support safe sequencing include progressive rotational strength training, emphasis on eccentric hip and trunk control, and restoration of hip internal/external rotation and thoracic mobility. Monitoring training load, employing motion-analysis feedback, and integrating neuromuscular drills that reinforce the correct temporal order will reduce tissue overload while incrementally improving power and accuracy.

Kinetic contributions of ground reaction forces and the kinetic chain: translating lower limb force into club head speed

Ground reaction forces (GRFs) are the primary external kinetic inputs that enable the transformation of lower‑limb effort into club head speed. The vertical component provides the impulse that stabilizes the trunk and permits effective rotational torque, while the horizontal (antero‑posterior and medio‑lateral) components generate shear and braking forces that accelerate the pelvis into rotation. Rate of force development and the timing of peak GRF relative to transition are both critical: an early, well‑timed lateral push produces a rapid transfer of momentum up the chain, whereas delayed or poorly directed GRF increases reliance on distal segments and reduces mechanical efficiency.

Efficient energy transfer follows a proximal‑to‑distal pattern driven by intersegmental torques and coordinated muscle activation.At the hips and pelvis, eccentric control of the lead side and concentric drive of the trail side create rotation and translational motion; the trunk converts that motion into angular velocity for the shoulders and arms; the wrists and club then exploit segmental inertia for final velocity amplification. This serial summation of segmental velocities depends on precise timing of joint moments, minimal counterproductive energy leakage, and appropriate stiffness at each linkage to preserve momentum rather than dissipate it.

| Segment | Illustrative contribution to club head speed |

|---|---|

| Lower limbs & GRF | ~25-35% |

| Pelvis & hips | ~20-30% |

| Trunk/shoulders | ~20-25% |

| Arms,wrists & club | ~15-25% |

Neuromuscular coordination that couples GRF to rotational output relies on precise center‑of‑pressure (COP) transitions and selective muscle recruitment.Key observable markers include a medial‑to‑lateral COP shift during downswing, an early burst in gluteal and adductor activity to generate pelvic torque, and a subsequent coordinated activation of the obliques and shoulder rotators to transmit energy. Practical coaching cues that reflect these biomechanical realities include:

- “Push-the ground, not the club” (emphasizes GRF initiation).

- “Lead the hips, then let the torso follow” (reinforces proximal‑to‑distal timing).

- “Maintain spine angle while allowing pelvic rotation” (protects against energy leakage and loss of plane).

From a training and injury‑prevention perspective, interventions should target GRF production, intersegmental stiffness regulation, and timing. Eccentric and concentric hip strength, unilateral power (plyometrics), anti‑rotation core stability, and ankle-foot proprioception all improve the capacity to generate and direct GRF.Objective monitoring with force plates, high‑speed kinematics, or inertial measurement units permits quantification of impulse, RFD, COP excursion, and sequencing-metrics that can be used to individualize technical and physical interventions while minimizing overload to the lumbar spine and shoulder complex.

Club head dynamics and impact biomechanics: club face orientation,effective mass,and energy transfer to the ball

Club face orientation at the instant of contact governs the primary determinants of ball flight: launch direction,spin axis,and initial spin rate. small angular deviations of the face relative to the target line produce proportionally larger changes in lateral launch and spin; likewise,the combination of **dynamic loft** and face angle determines overall spin magnitude. The phenomenon of gear effect-where off‑center impacts induce a coupling between club face rotation and ball spin-amplifies the influence of contact location, so that toe or heel strikes alter both lateral dispersion and backspin. precision in face control therefore operates as a first‑order constraint on performance outcomes,and measurement of face angle at impact (±0.5° resolution) is useful for both fitting and technical feedback.

Effective mass at impact is a kinematic‑kinetic property that reflects how much of the club-arm system resists acceleration during ball contact; it is not a fixed equipment parameter but a function of club geometry, swing mechanics, and contact location. Key contributors include:

- Contact point along the face (heel vs toe) – shifts effective mass and inertia.

- Shaft bend and flex timing – transiently alters perceived mass and energy flow.

- Wrist and forearm stiffness at impact – modulates energy transmission and contact duration.

- Clubhead design (mass distribution and MOI) – changes center of percussion and vibration damping.

| Metric | typical driver range | Relevance |

|---|---|---|

| Clubhead speed | 35-55 m/s | primary source of kinetic energy |

| Ball speed | 50-80 m/s | outcome of energy transfer |

| smash factor | 1.44-1.52 | Ball speed / club speed (efficiency) |

| Contact duration | 0.0004-0.0006 s | Short impulse, high peak forces |

Energy transfer at impact is governed by impulse-momentum relationships and the coefficient of restitution (COR) between the clubface and ball. The effective energy delivered to the ball equals the kinetic energy of the clubhead component aligned with the normal to the face times a transfer efficiency factor; this efficiency is influenced by COR, effective mass, and relative motion during contact. Short contact durations create large peak forces and require rapid tissue loading; the match between clubhead effective mass and the player’s ability to stabilize the distal segments at impact determines how much energy is absorbed by the ball versus dissipated in vibration and soft‑tissue deformation. Practically, smash factor (ball speed/club speed) provides a summary metric of transfer efficiency but must be interpreted alongside center‑of‑pressure and face‑angle data for diagnostic clarity.

From a technique and injury‑prevention perspective, optimizing club head dynamics requires concurrent attention to equipment fitting and neuromuscular control. Emphasize drills that: improve repeatable face orientation at impact,condition forearm-wrist stiffness to manage effective mass without creating excessive joint loading,and promote center‑face impacts to maximize MOI advantages. Equipment interventions (head weighting, shaft selection, and lie adjustments) should be prescribed using objective impact data and a player’s physical capacity. monitor training load and impact stress-particularly in golfers increasing swing speed-to reduce risk of overuse injuries in the wrist, elbow, and lumbar spine while preserving efficient energy transfer. Bold,measurable targets (e.g., consistent smash factor, low face‑angle variability, centered impacts) are practical end points for evidence‑based refinement.

Neuromuscular control and motor learning: muscle activation patterns, timing, and practice strategies for durable skill acquisition

The neuromuscular architecture underlying an effective golf swing is characterized by coordinated, task-specific recruitment of muscles that supports both power generation and fine-tuned control. Skilled performance depends on integrated feedforward commands that prepare the body for rapid ballistic motion and feedback-driven adjustments that correct for environmental variability.Contemporary kinematic and EMG studies converge on the view that golfers develop stable intermuscular synergies-functional groupings of muscles whose relative activation patterns reduce control dimensionality while preserving adaptability across varying swing contexts.

Sequencing and amplitude of muscle activation follow a robust proximal‑to‑distal cascade that optimizes energy transfer from the ground through the pelvis and thorax to the club. Key contributors include the hip extensors and rotators for weight shift and pelvis rotation, the trunk rotators and obliques for torso coil and uncoil, and the forearm/wrist complex for clubface control and impact damping. Practitioners should monitor and train these roles explicitly:

- hip complex: force generation and early rotation timing

- Trunk rotators: energy transfer and sequencing

- Scapular stabilizers: maintenance of arm-torso linkage

- Forearm/wrist musculature: impact modulation and fine control

Temporal precision-when activation occurs relative to kinematic events-is as important as which muscles are recruited.Optimal swings exhibit repeatable onset latencies and intermuscular phase relations, with beneficial low variability at impact yet moderate variability earlier in the motion to support adaptability.The following concise table summarizes typical temporal emphases for training interventions, presented for practical translation into coaching programs:

| Training Focus | Temporal Target | Practical Drill |

|---|---|---|

| Ground-to-hip drive | Early downswing (0-20% prior to pelvis rotation) | Explosive hip-drive reps with med ball |

| Trunk sequencing | Mid downswing (pelvis → thorax delay ~30-50 ms) | Slow-motion video + timed resisted swings |

| wrist timing | Late downswing → impact | Impact-focus drills with tee/impact tape |

Motor learning strategies that promote durable, transferable skill include variable practice, contextual interference, and reduced dependency on high-frequency augmented feedback. Empirical evidence supports practice designs that emphasize: spacing (distributed sessions over time), interleaving (mixing shot types), and external focus (attending to ball/target outcomes rather than body mechanics). Recommended components for a training block are:

- High variability sets to broaden the repertoire of sensorimotor mappings

- Low-frequency augmented feedback (e.g., summary or bandwidth feedback) to encourage intrinsic error detection

- Progressive complexity with realistic constraints to foster transfer to on‑course situations

integrating neuromuscular conditioning into skill training reduces injury risk and stabilizes performance under fatigue. Emphasize eccentric strength of the hip and trunk, pre‑activation drills for impact tolerance, and proprioceptive exercises that enhance joint position sense in the lumbar-pelvic and shoulder regions. Monitoring markers such as asymmetric EMG patterns, delayed pre‑activation, or rapidly increasing intra‑session variability can guide load management and individualized corrective programming to preserve both performance and musculoskeletal health.

Injury mechanisms and prevention: load thresholds, common pathologies, and targeted conditioning interventions

Load in the golf swing should be conceptualized as both acute peak magnitude and cumulative exposure. Acute peaks occur during transition and impact when axial rotation, lateral bending and ground reaction forces converge; cumulative loads arise from repeated practice and competition that produce microtrauma. Injury is therefore best predicted by the interaction of intensity, frequency and the athlete’s capacity to absorb load: increasing peak moments without concurrent increases in tissue tolerance elevates risk. Contemporary biomechanical models emphasize the distribution of loading across segments (hip-to-shoulder transfer) and the timing of muscle activation as primary determinants of whether a given load is adaptive or damaging.

Empirical and clinical literature identify several recurrent pathologies in golfers. Chronic low back pain is linked to repetitive lumbar rotation and high compressive/shear forces; medial and lateral epicondylalgia arise from repeated eccentric wrist/forearm loading during impact; rotator cuff tendinopathy and scapular dyskinesis reflect maladaptive shoulder mechanics and poor scapulothoracic control.In younger players, the presence of open physes increases susceptibility to growth-plate injuries, while underlying bone disorders (such as, conditions such as osteonecrosis or osteogenesis imperfecta) substantially alter fracture risk and mandate medical oversight.

Mechanistically, three phases concentrate injury risk: the transition (strain energy storage), impact (rapid deceleration and force transfer), and follow-through (eccentric dissipation). During these epochs, high torsional moments and sudden eccentric contractions create localized tissue strain beyond physiological thresholds, particularly when neuromuscular timing is compromised. Ground reaction force asymmetries and poor hip mobility increase compensatory rotation in the lumbar spine and shoulder, converting otherwise subclinical loads into clinically relevant injury events.

- Rotational core conditioning: anti-rotation and plyometric drills to improve torque transfer and reduce lumbar shear.

- Hip mobility and strength: targeted gluteal and hip-flexor work to optimize pelvis control and decrease lumbar compensation.

- Scapular and rotator cuff program: eccentric strengthening and motor control drills to stabilize the shoulder through acceleration and deceleration.

- Eccentric forearm conditioning: graded eccentric loading to raise tendon resilience and reduce epicondylar overload.

- load-management protocols: periodized practice volume, objective monitoring (RPE, swing counts) and progressive return-to-play criteria.

Practical prevention combines technique modification, conditioning and medical screening. Swing adjustments that moderate peak rotational velocities and distribute work toward larger proximal segments reduce local tissue stress. Conditioning should be periodized,integrating neuromuscular control,progressive eccentric loading and sport-specific power development; objective markers (training load,pain trends,and movement-quality screens) guide escalation. Where systemic bone pathology or unexplained pain exists, referral for imaging and specialist evaluation is indicated to exclude disorders such as osteonecrosis or congenital bone fragility before load intensification.

| injury | Primary mechanism | Targeted intervention |

|---|---|---|

| Low back pain | Repetitive torsion + poor hip transfer | Rotational core & hip strength |

| Medial epicondylalgia | Eccentric wrist/forearm overload | Graded eccentric forearm training |

| Rotator cuff tendinopathy | Scapular dyskinesis & deceleration loads | Scapular control + eccentric RC work |

| growth-plate stress (youth) | Excessive repetitive load during skeletal maturation | Volume limits & coach-supervised technique |

Implementation is multidisciplinary: coaches, biomechanists, physiotherapists and physicians must align on load-capacity targets, monitoring strategies and staged interventions. Emphasize objective progression, movement-quality thresholds and athlete education on symptom recognition. The most effective prevention programs combine targeted conditioning, quantified load control and early medical evaluation when pain patterns suggest structural compromise-thereby preserving performance while minimizing injury incidence.

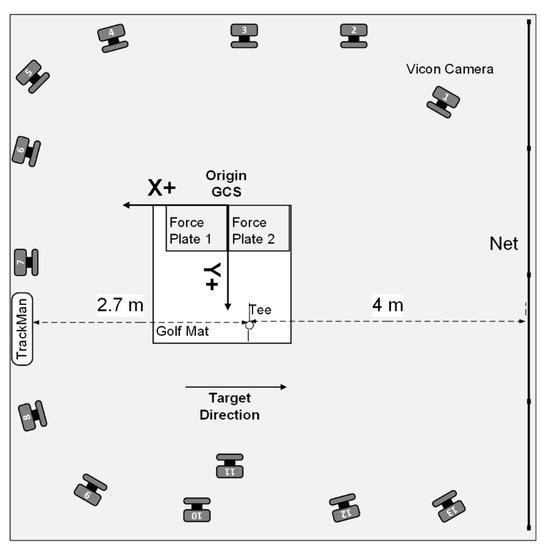

Assessment tools and measurement protocols: motion capture, force platforms, EMG, and wearable sensors for applied coaching

Applied measurement in golf biomechanics requires aligning instrumentation with the specific assessment question: whether the goal is to quantify kinematic consistency, kinetic transfer, neuromuscular timing, or to provide real‑time feedback for skill acquisition. Selection of tools should thus follow the same pragmatic testing principles used in other assessment domains-the instrument must be valid, reliable, and appropriate for the construct of interest. In practice this means combining complementary systems (e.g.,motion capture + force platforms + EMG) when examining energy transfer and sequencing,or selecting wearable IMUs when ecological validity and on‑course portability are primary constraints.

Optical motion capture remains the gold standard for three‑dimensional kinematics when high spatial accuracy is required. For laboratory protocols use a multi‑camera, calibrated volume with a standardized marker set or validated markerless algorithms; typical recommendations are ≥200 Hz for golf swing analysis to resolve high angular velocities. Rigid body modeling, joint center estimation, and consistent skin marker protocols reduce artifact-report model definitions, filtering cutoffs (e.g., low‑pass Butterworth, cutoffs justified by residual analysis), and intertrial calibration procedures to ensure reproducibility. When markerless systems are used, document algorithm versioning and validation against a marker system to support coaching decisions.

Force platforms provide the kinetic counterpart: tri‑axial ground reaction forces, center of pressure trajectories, and interlimb weight shift metrics that quantify how lower‑body force is generated and transferred through the chain. Use dual force plates for self-reliant feet measures and sample at ≥1000 Hz when synchronizing with high‑speed kinematics to capture impact transients. Protocols should define stance placement, warm‑up swings, and gating for swing phases (backswing, transition, impact, follow‑through). Always report calibration checks, vertical force drift corrections, and how moments are referenced to segment coordinate systems to avoid misinterpretation of torque transfer metrics.

Surface EMG provides insight into timing, magnitude, and sequencing of muscle activation but requires rigorous preprocessing and normalization for meaningful comparisons. Adopt skin preparation, electrode placement over standardized anatomical landmarks, and normalization to maximal voluntary contraction (MVC) or submaximal task references; apply band‑pass filtering (commonly 10-450 Hz), notch filtering as needed for mains interference, and consistent rectification and smoothing (e.g., RMS window) before extracting onset, peak, and onset‑to‑peak latency metrics. Recognise limitations: crosstalk,amplitude variability,and the indirect relation between EMG amplitude and force,and use EMG primarily for temporal sequencing and relative activation pattern analyses for coaching interventions.

Wearable sensors (IMUs, pressure insoles, instrumented gloves) extend measurement into on‑course and high‑throughput coaching environments by trading some accuracy for portability and immediacy. They are particularly useful for longitudinal monitoring, swing variability metrics, and delivering real‑time biofeedback. For applied coaching consider these practical applications:

- Immediate kinematic cues (clubhead speed, shoulder turn, tempo)

- Balance and weight‑shift monitoring using pressure insoles or force‑plate proxies

- Sequencing alerts derived from combined IMU + EMG logic

Below is a concise comparison of typical sampling regimes and primary outputs to guide tool selection (values are indicative):

| Tool | Typical Sampling | primary Outputs |

|---|---|---|

| Optical Motion Capture | 200-1000 Hz | Joint angles, segment velocities |

| Force Platform | 1000-2000 Hz | GRF, COP, interlimb force |

| Surface EMG | 1000-2000 Hz | Activation timing, RMS amplitude |

| Wearables (IMU/pressure) | 100-1000 Hz | Angular velocity, acceleration, pressure maps |

Integrating multiple streams requires rigorous synchronization, clear preprocessing, and decision rules that translate measured constructs into actionable coaching cues; documenting these protocols is essential for reproducible, evidence‑based practice.

Evidence based technique refinement and coaching recommendations: translating biomechanical findings into training prescriptions

Contemporary coaching should translate quantified biomechanical findings-kinematics, kinetics and neuromuscular patterns-into precise, measurable coaching targets. Emphasize **objective markers** (e.g., pelvis-torso separation, peak angular velocity, ground-reaction force timing) and convert them into observable outcomes for practice. When coaches anchor instruction to reliable metrics rather than vague aesthetic ideals, interventions become testable and reproducible across athletes and sessions.

Practical technique refinements follow from specific deficits identified in assessment. the following coaching foci are evidence-aligned and easily integrated into practice:

- Segmental sequencing: drills that emphasize early pelvis rotation followed by torso acceleration to restore proximal-to-distal energy transfer.

- Force application timing: radial and vertical ground-reaction force (GRF) drills on full swings to synchronize weight transfer with downswing acceleration.

- Mobility paired with stability: combined thoracic rotation mobility and anti-rotation core loading to permit safe high-velocity rotation.

- External-focus cueing: concise, outcome-directed cues (e.g., “feel the clubhead accelerate through impact”) to enhance automaticity and transfer.

To operationalize these prescriptions, use concise progressions and measurable tests. The table below maps representative biomechanical markers to simple metrics and targeted training actions for routine implementation in a coaching plan.

| Biomechanical Marker | Measured Metric | Training Prescription |

|---|---|---|

| Segment separation (X‑factor) | Pelvis-torso angular difference (°) | Rotational mobility + sequencing drills |

| Push-off timing | Peak horizontal GRF latency (ms) | force‑plate tempo training; step‑through drills |

| Trunk control on downswing | Lateral acceleration / sway (m·s⁻²) | Anti‑rotation core progressions; mirror feedback |

Training design must integrate motor learning principles and load management. Use variable practice,faded augmented feedback,and contextual interference to promote adaptability while limiting injury risk-particularly when increasing rotational speed or ground forces. Recommended session scaffolding includes:

- warm-up: dynamic mobility and activation targeted to identified deficits.

- Focused block: 10-20 minutes of targeted drills (sequencing, GRF timing, or stability).

- Integration: progressive return to full swings with feedback reduction.

- Objective testing: short battery of metric checks (video,inertial sensors or force plates) to record progress.

implement an iterative,data‑driven coaching cycle: assess → prescribe → monitor → adapt. Use low‑cost technologies (high‑speed video,IMUs) and periodic lab metrics (force plates,motion capture) when available to set thresholds for progression and return‑to‑play. Prioritize reproducibility in measurement and documentable outcomes so technique refinement becomes a defensible, scalable component of long‑term player development.

Q&A

1) Q: What is biomechanics and how is it applied to the study of the golf swing?

A: Biomechanics is the application of mechanical principles to biological systems to describe, analyze, and predict movement and force interactions (see general definitions in biomechanics education resources). in the context of the golf swing, biomechanics integrates kinematics (motion without regard to forces), kinetics (forces and moments that cause motion), and neuromuscular control (muscle activation and coordination) to characterize the sequence of motions, quantify performance determinants (e.g., clubhead speed, launch conditions), and identify movement patterns associated with injury risk. This multidisciplinary approach supports objective assessment, technique refinement, training prescription, and injury prevention.

2) Q: What are the main phases of the golf swing that biomechanical analyses commonly examine?

A: Standard phase segmentation includes: address/setup, takeaway/early backswing, mid- to late-backswing, transition, downswing, impact, and follow-through. Biomechanical analysis typically quantifies joint angles, segment velocities, intersegmental timing, ground reaction forces, and muscle activity across these phases to understand how energy is stored, transferred, and released through the kinetic chain.

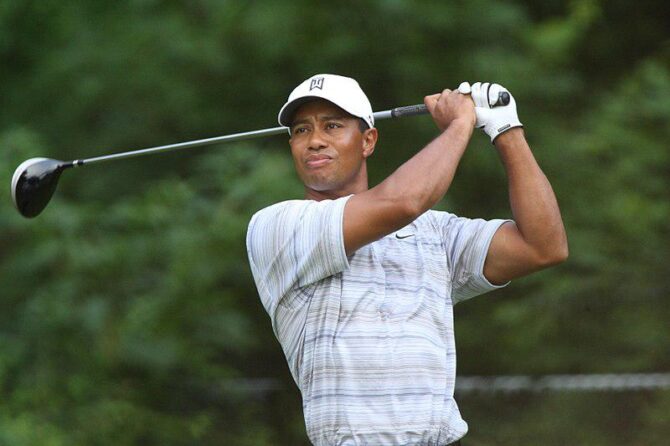

3) Q: Which kinematic variables are most predictive of performance (e.g., clubhead speed and ball velocity)?

A: Primary kinematic predictors include proximal-to-distal sequencing (timing of pelvis, trunk, upper arm, forearm, and club peak angular velocities), maximal angular velocities of the pelvis and trunk, shoulder-pelvis separation (X-factor) and its rate of stretch, wrist **** magnitude and release timing, and the velocity of the clubhead at impact. Efficient sequencing-where larger, proximal segments peak earlier and distal segments later-supports transfer of angular momentum and maximizes clubhead speed.

4) Q: How do kinetic factors contribute to generating clubhead speed?

A: Kinetic contributors include ground reaction forces (vertical and shear), moments and torques at the hips, trunk, and shoulders, and impulse generated by leg and core musculature.Force generation against the ground provides a foundation for rotational torque; coordinated application of these forces creates intersegmental moments that accelerate proximal segments and sequentially transfer energy distally. Timing of force production (e.g., rapid weight shift and vertical ground force spike during downswing) is critical.

5) Q: What is the role of neuromuscular dynamics and motor control in an effective golf swing?

A: Neuromuscular dynamics determine the timing, magnitude, and coordination of muscle contractions responsible for joint torques and segment accelerations. Electromyography (EMG) studies show phase-specific activation patterns-early activation of lower-limb and trunk extensors followed by trunk rotators and upper-limb muscles-that enable the proximal-to-distal sequence. Motor control processes manage intersegmental coordination, adapt to changing environmental constraints (club type, lie), and ensure consistency via feedforward planning and sensory feedback.

6) Q: What is the “X-factor” and how does it affect performance and injury risk?

A: the X-factor denotes the angular separation between the pelvis and thorax (or shoulders) at the top of the backswing. Larger separation and a rapid increase in separation during the early downswing (X-factor stretch) are associated with greater elastic energy storage in trunk tissues and higher potential clubhead speeds. However, excessive X-factor or rapid unprotected torsion can increase shear and compressive loading on the lumbar spine, elevating risk for lower back injury if not supported by adequate trunk strength and mobility.

7) Q: Which injuries are most commonly associated with the golf swing, and what biomechanical mechanisms underlie them?

A: Common injuries include low back pain, rotator cuff and labral shoulder injuries, medial/lateral epicondylalgia (elbow), and wrist/hand pathologies. Mechanisms include repetitive high torsional and shear loads on the lumbar spine (poor rotation timing, loss of hip mobility), eccentric overload of rotator cuff and scapular stabilizers during transition and follow-through, repetitive valgus/varus and extension stress at the elbow from poor club release or swing path, and sudden impact/load transients transmitted to the wrist. Poor technique, inadequate conditioning, and high practice volume compound these risks.

8) Q: what assessment tools and measurement technologies are used in golf biomechanics research and practice?

A: Common tools include 3D optical motion capture (gold standard for kinematics), inertial measurement units (IMUs) for field-based kinematics, force plates for ground reaction forces and center-of-pressure analysis, electromyography (EMG) for muscle activation, pressure-sensing insoles, high-speed video, launch monitors (ball and club metrics), and musculoskeletal modeling software to estimate joint loads and muscle forces.each tool has trade-offs in accuracy, ecological validity, and accessibility.

9) Q: How can biomechanical data inform technique refinement for players and coaches?

A: Objective metrics (e.g., sequencing timings, peak segment velocities, ground reaction force patterns, X-factor magnitude and velocity) allow identification of inefficiencies and deviations from desired patterns. Coaches can use these insights to prioritize interventions (mobility vs. strength vs. motor control) and select drills that target identified deficits. For example, delayed trunk rotation or insufficient weight shift suggests drills emphasizing hip initiation and ground force application; poor distal timing can be addressed with tempo and release drills.

10) Q: What training interventions have empirical support for improving swing mechanics and performance?

A: Evidence supports multidimensional programs combining strength and power training (hip and trunk rotational strength, lower-limb force development), mobility/versatility work (thoracic rotation, hip internal/external rotation), neuromuscular training (coordination, balance, proprioception), and task-specific practice (swing repetitions with variable constraints). Plyometrics and resisted rotational power exercises can increase rate of force development and clubhead speed. interventions are most effective when individualized to address the athlete’s specific biomechanical deficits.

11) Q: Which drills or practice strategies translate best from biomechanical principles to the driving range?

A: drills that emphasize proximal initiation, sequence timing, and ground force application – for example: step-and-rotate or step-through swings to promote weight shift; medicine-ball rotational throws to train power transfer; tempo/pausing drills to improve transition timing; swing-with-resistance (bands or weighted clubs) to enhance force production while preserving technique; and mirror/video feedback for positional awareness. Use of immediate objective feedback (IMU metrics, launch monitor data) accelerates motor learning by making error signals salient.

12) Q: How should clinicians and coaches monitor injury risk and manage return-to-play?

A: Monitor workload (sessions, swings, intensity), movement quality (trunk and hip mobility, sequencing integrity), and pain or compensatory patterns.Use progressive, criterion-based return-to-play that restores adequate strength, power, and neuromuscular control under sport-specific loads.Address modifiable risk factors (technique faults, limited hip or thoracic mobility, core weakness) and incorporate maintenance programs for mobility and strength. Regular screening (movement screens,functional tests,swing metrics) can detect early deterioration.

13) Q: What methodological limitations should readers be aware of in current golf biomechanics research?

A: Limitations include small sample sizes, heterogeneous participant skill levels, laboratory constraints that may alter natural swing behavior, differences in measurement systems and processing methods that reduce comparability, cross-sectional designs limiting causal inference, and underrepresentation of female and older golfers. Musculoskeletal models often rely on assumptions for muscle forces and joint centers,producing estimates rather than direct measures of internal loads.14) Q: What practical recommendations arise from biomechanical evidence for coaches working with golfers?

A: Prioritize (1) quality movement patterns over quantity of practice; (2) proximal-to-distal sequencing through drills and motor control training; (3) adequate hip and thoracic mobility to allow rotation without compensatory lumbar motion; (4) lower-limb force and rate-of-force-development training to improve ground force transfer; (5) individualized conditioning to address asymmetries and deficits; and (6) objective monitoring (IMU or launch monitor metrics) to quantify progress and guide load management.

15) Q: How can measurement technologies be integrated into routine coaching without disrupting ecological validity?

A: use portable IMUs, high-speed video, launch monitors, and pressure-sensing insoles to capture relevant metrics on the range. Favor minimal-intrusion devices and quick protocols (warm-up, standardized swings) and combine objective metrics with expert observational analysis. Periodic lab-based assessment (3D motion capture, force plates) can supplement field measures for comprehensive evaluation while preserving realistic practice conditions for most coaching sessions.

16) Q: What future directions and research gaps are most important for advancing biomechanics-informed golf practice?

A: Priorities include larger longitudinal intervention trials linking specific biomechanical targets to performance and injury outcomes; improved field-validated sensor fusion algorithms for accurate kinematics and kinetics outside the lab; sex- and age-specific normative datasets; integration of neuromechanical models that couple muscle activation, fatigue, and tissue loading; and translational research on optimal periodization and dose-response relationships for swing training and injury prevention.

17) Q: How should academic readers interpret biomechanical findings in light of individual variability?

A: Biomechanical “benchmarks” should be applied as informative guides rather than prescriptive rules. inter-individual differences in anatomy, prior injury, mobility, and motor learning capacity mean that optimal technique is frequently enough person-specific. Use biomechanical measures to define individual baselines, identify limited or maladaptive patterns, and design tailored interventions while monitoring functional and performance outcomes.

18) Q: What are concise take-home messages from a biomechanics perspective on improving golf technique and reducing injury?

A: (1) Efficient proximal-to-distal sequencing and effective ground force application are central to maximizing clubhead speed.(2) Adequate hip and thoracic mobility plus trunk strength protect the lumbar spine while enabling desirable X-factor mechanics. (3) Combine objective measurement with individualized conditioning and task-specific practice. (4) Monitor workload and movement quality to mitigate overuse injuries.(5) Translate lab insights pragmatically with portable technologies and evidence-based drills.If you would like,I can convert these Q&A items into a one-page executive summary for coaches,a technical appendix with suggested measurement protocols,or a bibliography of seminal studies in golf biomechanics.

The Way Forward

In closing, the biomechanical study of the golf swing synthesizes kinematic description, kinetic analysis, and neuromuscular dynamics to move beyond anecdote toward an evidence-based understanding of performance and injury mitigation. Framing the swing within the broader discipline of biomechanics-whose methods quantify how muscles, bones, tendons, and external forces produce and constrain movement-permits precise identification of mechanical drivers of ball launch conditions, and also the pathological loading patterns that elevate injury risk. This integrative perspective clarifies which technical elements are functionally essential,which are individual adaptations,and which constitute maladaptive strategies to be corrected.

For practitioners, coaches, and clinicians, the principal imperative is translation: apply objective measurement (motion capture, force platforms, wearable sensors) and validated analytic models to tailor instruction and rehabilitation to the individual athlete. Emphasizing movement quality-efficient sequencing of segmental rotation, optimized ground reaction force utilization, and neuromuscular coordination-supports both performance gains and tissue protection. Equipment selection and conditioning programs should likewise be informed by biomechanical evaluation,with strength,mobility,and motor control interventions targeted to the impairments that most strongly predict swing dysfunction or overload.

Looking forward, progress will depend on longitudinal, multidisciplinary research that couples high-fidelity measurement with ecological validity, computational modeling, and randomized trials of technique and training interventions. Greater integration of individualized modeling, real-time feedback technologies, and pragmatic clinical trials will enable more precise, scalable guidance for golfers across skill levels. Ultimately, by grounding coaching and clinical practice in rigorous biomechanical principles, the golf community can advance toward safer, more effective technique refinement-enhancing performance while minimizing injury burden.

Biomechanics of the Golf Swing: Principles and Practice

Why biomechanics matters for your golf swing

Understanding golf biomechanics converts vague advice into repeatable mechanics. When you apply biomechanical principles to your golf swing you improve:

- Consistency of ball striking and clubface control

- Rotational power and clubhead speed for more distance

- Injury resilience through efficient force distribution

- Shot predictability by optimizing timing and tempo

Fundamental biomechanical principles for a better golf swing

Kinematic sequence (the power pathway)

The kinematic sequence describes the order and timing of segmental rotations – pelvis, torso, arms, then club. A proper sequence transfers energy up the kinetic chain and maximizes clubhead speed with minimal effort. Typical elite sequence:

- pelvis starts rotating towards target

- Torso follows with a slightly delayed rotation

- Arms accelerate and extend

- Club releases with maximal angular velocity

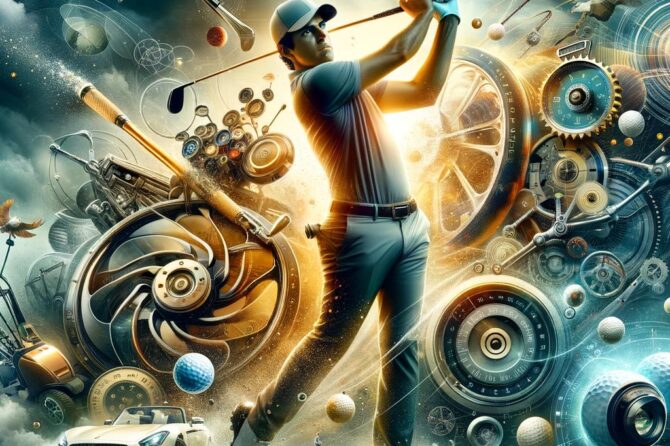

Ground reaction forces (GRF) and stance

Good swings convert vertical and horizontal forces from the ground into rotational momentum. Increasing GRF through stable footing and dynamic weight shift produces greater driving force and more consistent contact.

Kinetic chain efficiency

Efficient transfer of energy requires coordinated motion among ankles,knees,hips,spine,shoulders,and wrists. Breaks or compensation in any link reduce distance and increase injury risk.

Torque, angular momentum and stretch-shortening cycle

Rotational torque across the core and shoulders builds angular momentum. Pre-loading the core and shoulder complex (the stretch-shortening cycle) stores elastic energy and releases it during the downswing for explosive clubhead speed.

centre of pressure and balance

Managing center of pressure (COP) helps you maintain balance during transition and impact. Excessive sway or lateral head movement disrupts the swing plane and timing.

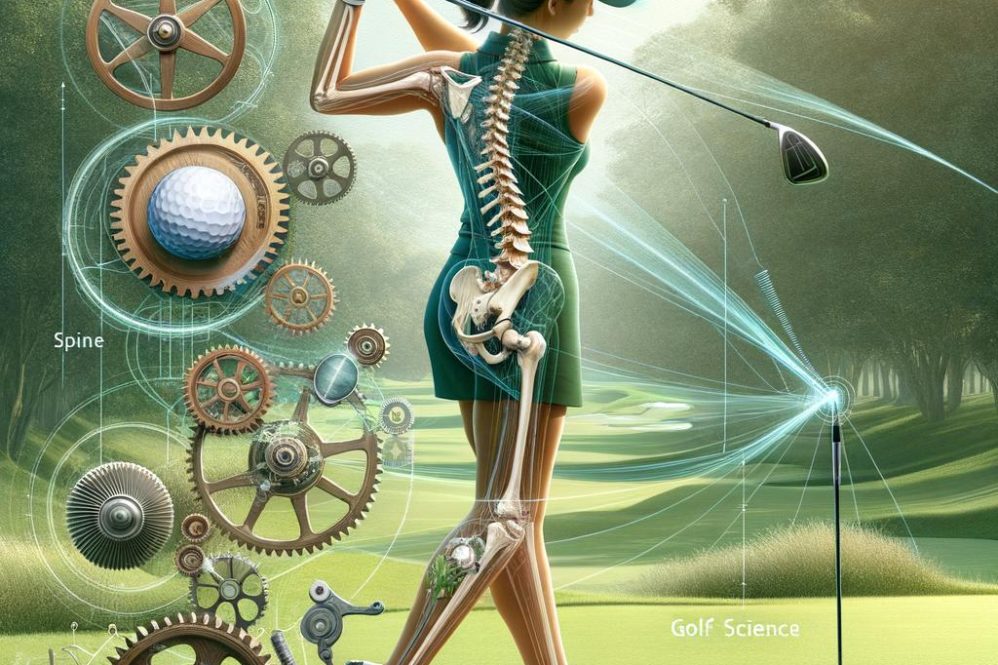

Anatomy of the swing: joints, muscles and roles

These are the primary body regions involved in the golf swing and their biomechanical roles.

| Body region | Primary role | Simple corrective drill |

|---|---|---|

| Hips / pelvis | Initiate rotation; generate power | Step-and-rotate drill |

| Thorax / Core | Transfer and amplify torque | Medicine ball woodchops |

| Shoulders | Control swing plane & club path | Rotational band swings |

| Wrists / Forearms | Manage clubface & release | Impact bag wrist drill |

| Legs / Ankles | Stability; generate GRF | Single-leg balance with med ball |

Grip mechanics, posture & alignment

Grip, posture, and alignment are the stable foundation for the kinetic chain. Small changes here cascade into large swing outcomes.

- Grip: Neutral to slightly strong depending on shot shape. Ensure both hands work together-pressure should be firm but not death grip. Check lead wrist posture at address.

- Posture: slight knee flex, hip hinge, spine angle maintained through swing.Avoid excessive vertical spine movement.

- Alignment: Aim feet, hips, and shoulders parallel to target line. proper alignment reduces compensations and improves shot shaping.

Swing tempo, timing & sequencing drills

Tempo and timing are the “rhythm” that synchronizes the kinematic sequence. Here are drills that directly train biomechanical timing:

- Counted tempo: 3-1-2 rhythm (takeaway = 3, transition pause = 1, downswing to impact = 2)

- Step-and-swing: Start with feet together, step into stance on takeaway to teach weight shift and sequencing

- Impact bag drill: Helps train hands-through impact and solid contact, improving clubface control

Common swing faults and biomechanical corrections

Understanding the mechanical cause of a fault is key to making efficient changes. Below are common problems, likely biomechanical causes, and suggested fixes.

- Slice: Cause – open clubface at impact due to early release or weak wrist set. Fix – strengthen lead wrist at address, drill with impact bag and half-swings focusing on squaring the face.

- Hook: Cause – over-rotation of forearms or late release. Fix – shallow the swing plane, limit excessive forearm pronation with slow-motion swings.

- Loss of distance: Cause – poor kinematic sequence or lack of GRF. Fix – rotational power drills (medicine ball throws), and ground-force training.

- Inconsistent strikes: Cause – poor weight transfer or sway. Fix – feet-base stability drills, step-and-rotate, and slow-motion impact-focused reps.

Training methods, technology & measurement

Modern training pairs classic coaching with objective measurement tools that reveal biomechanical details you can’t feel.

- 3D motion capture: Detailed kinematic sequencing, joint angles, and timing analysis.

- Launch monitors: Measure ball speed, smash factor, launch angle, spin – link clubhead mechanics to ball results.

- Force plates: Quantify ground reaction forces and weight shift patterns.

- Wearable sensors: provide real-time tempo, clubhead speed, and rotational metrics on the range.

Practice drills and strength exercises that apply biomechanics

Combine on-range drills with gym work to build an efficient, resilient golf swing.

On-range drills

- Slow-motion kinematic swings: Perform swings at 50% speed focusing on pelvis → torso → arms → club sequence.

- Impact bag hits: Develop forward shaft lean and solid compression.

- Alignment rod gate: Place rods to practice correct swing path and reduce over-the-top moves.

Gym & mobility

- Medicine ball rotational throws: Build explosive core rotation and reinforce sequencing.

- Single-leg Romanian deadlifts: Improve hip stability and GRF control.

- Thoracic rotation mobility: Cable chops and thoracic foam mobilizations to preserve upper-spine rotation ability.

Case study: Adding 10-15 yards to driver distance with biomechanics

Player profile: amateur golfer, mid-40s, 95 mph driver swing speed, inconsistent strikes, slight sway.

Assessment findings:

- Poor weight transfer-GRF asymmetry left to right

- early arm-dominant release-weak kinematic sequencing

- Limited thoracic rotation

Intervention (8 weeks):

- Technique: Step-and-rotate and slow kinematic sequencing drills to re-time pelvis → torso → arms

- Strength & Mobility: Medicine ball rotational throws, thoracic mobility sessions, single-leg stability work

- Measurement: Baseline and follow-up launch monitor sessions; force plate snapshots

outcome: Clubhead speed increased to 102 mph, ball speed rose proportionally, strike dispersion tightened, average carry improved by 12 yards. Improvements traced to better GRF usage, improved sequencing, and increased thoracic rotation.

Practical on-course checklist (fast biomechanics audit)

- Does your pelvis lead the downswing? (If not, practice step-and-rotate)

- Are you keeping a consistent spine angle through impact?

- Are you using ground forces rather than just arm strength?

- Is your clubface square at impact on neutral shots?

- Is your tempo consistent between practice sessions and on-course pressure shots?

SEO & content tips for golf instructors and coaches

If you publish content about golf biomechanics or golf swing technique, using these SEO-friendly keyword clusters naturally increases visibility:

- Primary: golf biomechanics, golf swing biomechanics, golf swing

- Secondary: clubface control, swing tempo, rotational power, golf posture, driver distance

- Long-tail: how to improve golf swing sequencing, drills for golf ground reaction force, thoracic rotation golf drills

Use headers (H2/H3) with keywords, include images and captions (e.g., “Kinematic sequence in the golf swing”), add short video clips of drills, and include measurable before/after stats or case studies to increase engagement and authority.

References & further reading

- Introductory biomechanics resources – biomechanics principles and human movement (for foundational understanding)

- Applied golf research and motion capture studies – search academic journals for “kinematic sequence golf swing” and force plate golf studies

Use this article to build a practice plan: assess your swing with simple drills, pair targeted gym work to correct weaknesses, and measure progress with a launch monitor or video. The more you translate biomechanical concepts into specific drills and measurable outcomes, the faster you’ll improve clubhead speed, control, and consistency.