Introduction

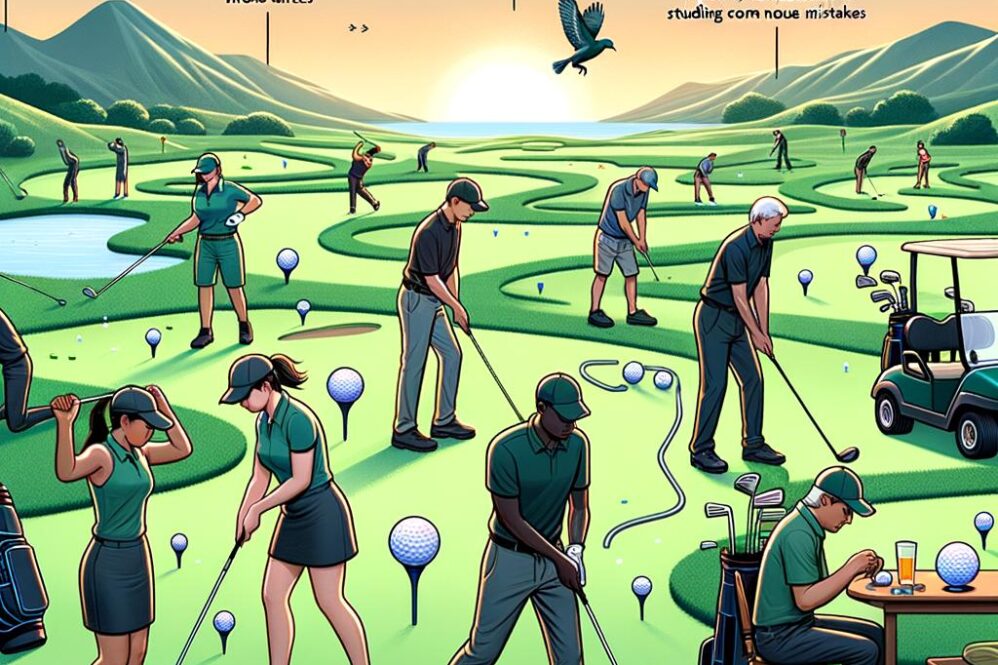

Golf participation continues to grow globally, yet the initial learning phase remains marked by persistent technical errors that limit performance, increase injury risk, and reduce long-term engagement. Many beginners, or “novices,” thus fail to translate practice into reliable on-course competence. The term novice denotes an individual who is inexperienced or new to an activity (Collins; Cambridge Dictionary; Vocabulary.com), and in the golf context describes players who have limited exposure to structured instruction, constrained task-specific motor patterns, and an underdeveloped perceptual-motor repertoire. Understanding the characteristic errors of this population and applying empirically grounded corrective strategies is essential for efficient skill acquisition and safe participation.

This article examines eight common novice golf mistakes-grip, stance, alignment, posture, swing path, tempo, ball position, and short-game technique-and synthesizes evidence-based fixes drawn from biomechanics, motor-learning theory, and coaching science. For each error we identify the typical manifestation, explicate the underlying mechanical or cognitive contributors, and recommend targeted interventions that are practical, measurable, and scalable for coaches and self-directed learners. Interventions emphasize principles shown to support durable learning (e.g., salient feedback, progressive constraints manipulation, and variability of practice) as well as movement solutions that reduce injury risk.

By integrating contemporary theory with applied drills and assessment cues, the goal of this review is to equip instructors and novice golfers with a concise, practically oriented framework that accelerates skill transfer and promotes safe, enjoyable play. The following sections detail the empirical rationale for each corrective strategy and provide implementation guidance suitable for use in lesson settings, practice sessions, and player-led training.

grip Mechanics and Evidence Based Adjustments to Enhance Clubface Control

Clubface orientation at impact is the primary determinant of initial ball direction; thus, small deviations in hand placement and pressure produce disproportionately large changes in dispersion. Contemporary coaching emphasizes the relationship between wrist axis, forearm rotation, and the lie created by the grip rather than purely aesthetic hand positions. Practically, this means adopting a grip that promotes a repeatable wrist hinge and forearm supination/pronation cycle while minimizing compensatory wrist collapse. Grip pressure and the balance between finger and palm contact are central variables: excessive palm engagement increases grip torque,while excessive finger-only contact reduces control under load.

Novice patterns characteristically fall into a few repeatable error-types: overly strong or weak rotations of the hands,excessive squeezing (the “death grip”),and inconsistent finger placement. The following table summarizes typical outcomes and concise corrective emphases used by coaches.

| Observed Grip | Typical Ball Flight | Correction Focus |

|---|---|---|

| Strong (rightward V) | Hook or closed face | rotate right hand slightly left; chest-point check |

| Weak (leftward V) | Slice or open face | Rotate right hand slightly right; split-grip drill |

| Death grip | Blocked shots, loss of feel | Lighten to 4-6/10 pressure; fingertip emphasis |

Evidence-informed adjustments are procedural and measurable. Coaches recommend a neutral reference (V-shapes formed by the thumb/index finger pointing to or just right of the trailing shoulder for right-handed golfers), combined with a target pressure band of approximately 4-6 out of 10 to allow both control and dynamic release.Effective drills include:

- mirror-address checks for V alignment;

- towel-under-arms to maintain connection and reduce excessive wrist motion;

- short-swing strikes focusing on maintaining the same hand-frame through impact.

These drills produce rapid proprioceptive feedback and have been shown in motor-learning literature to accelerate retention when practiced with reduced variability and high frequency.

Objective monitoring accelerates improvement and reduces guesswork. Use slow-motion video to inspect wrist set and face angle at impact and, when available, a launch monitor to track face angle, spin axis and dispersion pre/post adjustment. Pressure-mapping grips and simple in-hand sensors can quantify pressure distribution changes as golfers adopt fingertip-dominant contact. From an injury-prevention standpoint, incremental loading and avoidance of forced supination/pronation reduce strain on the ulnar and radial wrist structures; emphasize incremental reps and recovery for novices building new motor patterns.

Integrating grip refinement into structured practice ensures transfer to on-course performance. Begin sessions with 10-15 minutes of focused grip drills, progress to half-swings and then full swings while recording face-angle metrics, and conclude with short-game work that preserves the new feel. keep a short checklist for each practice session:

- V alignment at address;

- Pressure within 4-6/10;

- Fingertip contact prioritized over palm clench;

- Consistent finish position showing release.

Consistent request of these evidence-based adjustments will reduce face-angle variability and improve directional control over time.

stance Width and Weight Distribution: Biomechanical Strategies for Stability and Power

Stance width fundamentally determines the golfer’s base of support and the mechanical leverage available for generating clubhead speed. From a biomechanical perspective, a wider stance increases frontal-plane stability by enlarging the base of support, while a narrower stance can facilitate greater rotational mobility around the vertical axis. Empirical studies in human movement science indicate that optimal stance width is a function of anthropometrics and task demands; thus, coaching prescriptions should prioritize functional stability without unduly constraining torso rotation. Stability and mobility should be treated as a complementary continuum rather than mutually exclusive objectives.

Practical recommendations can be summarized by club type and performance goal: shorter clubs favor precision and tighter stances,long clubs favor power and slightly wider stances. The table below provides concise, evidence-informed guidance that practitioners can use as an initial baseline; individualization is required through movement screening and on-course testing.

| Club Group | Suggested stance Width | Working Weight Distribution |

|---|---|---|

| Wedges / Irons (short) | Heel-to-heel (~shoulder width) | 60% front (address) → 50:50 at impact |

| Mid-Irons | Shoulder width | 55% front (address) → 45:55 at impact |

| Driver / Woods | Slightly wider than shoulders | 50% front (address) → 40:60 at impact |

Weight distribution is not static; it is a dynamic variable that should be coordinated with the sequence of the golf swing. At address a slightly forward-biased distribution (e.g., 55-60% toward the lead foot for iron play) can promote downward strike, whereas drivers typically benefit from a more centered or even slightly rear-biased address to allow upward angle of attack. During the backswing the center of pressure shifts rearward; efficient transfers occur when the hips and torso manage that shift smoothly so the downswing can re-establish a forward COP at impact. Emphasizing center-of-pressure awareness reduces compensatory movements such as early extension or lateral slide.

Coachable, evidence-based drills help embed the appropriate stance and weight strategies into motor patterns. Recommended exercises include:

- Feet-spacing ladder: mark incremental stance widths and hit 10 balls at each width to record dispersion and ball flight.

- Weight-transfer line: place a low board under the lead foot to provide tactile feedback for forward pressure at impact.

- Single-leg balance progressions: improve unilateral stability to reduce excessive lateral sway in the swing.

- Pressure-mapping drills: use inexpensive force-sensing insoles for objective COP feedback during practice swings.

These drills are selected to target both neural adaptation and mechanical consistency.

integrate objective measurement and progressive overload when modifying stance and weight cues. Begin with small, testable changes (±1-3 cm stance width; ±5-10% weight redistribution) and quantify outcomes-clubhead speed, shot dispersion, and contact quality-before further adjustment. In clinical or high-performance settings, combine kinematic observation with force-plate or pressure-insole data to validate that changes in stance width enhance both stability and power without introducing compensatory strain patterns. Consistent, data-informed practice yields durable improvements in both accuracy and distance.

Alignment principles and Targeting Practices to Improve Shot Accuracy

Consistent shot accuracy is grounded in a reproducible geometric relationship between the player,the clubface,and an external target. Small deviations in aim produce disproportionately large lateral errors at distance; for example, a 2° misalignment at address can produce a miss of several yards at 150-200 yards. Therefore, precision begins with a systematic approach to visualizing and establishing the target line and maintaining that reference through the setup and takeaway. Adopting a measured routine transforms alignment from an implicit intuition into an explicit, repeatable input to every swing.

Establish a pre-shot checklist that converts perception into measurable actions. Before initiating the swing, experts recommend verifying these elements in sequence:

- Clubface – point the face at a precise aim point (a spot on the ground, not the flag).

- Feet & Hips – align parallel to the intended target line, not to an imagined fairway path.

- Shoulders – set square to the same line as the feet and hips.

- Visual Focus – select an intermediate target 1-3 yards in front of the ball to bridge the eye-target-ball relationship.

Executing these checks as a standardized sequence reduces variability and cognitive load during play.

Practical drills and objective aids accelerate motor learning and perceptual calibration. Use alignment sticks, a narrow mat edge, or tee lines to create clear visual references during practice; apply progressive narrowing of the target area to build accuracy under pressure.The following compact table summarizes common diagnostic observations and concise corrective drills useful in practice sessions (WordPress styling applied):

| Element | Diagnostic | Corrective Drill |

|---|---|---|

| Clubface | Face points left/right of aim | Face-to-target alignment drill |

| Stance | Feet/hips closed or open | Gate-step alignment drill |

| Aim Point | Inconsistent visual pick | Dot-target progressive narrowing |

Empirical studies in motor control show that intentional focus on external outcomes (a precise target) improves consistency more than internal focus on body segments. Translating this into practice, prioritize external-aim drills and quantify results: record dispersion patterns for 20 shots with an alignment protocol, then adjust one variable (e.g., clubface orientation) and re-test. Use video or a simple alignment-stick photo to measure degrees of misalignment – objective feedback closes the perceptual loop and speeds correction compared to subjective feels alone.

Coaching cues should be concise, externally oriented, and progressively demanding. Begin sessions with large, forgiving targets and simple alignment references; once the student demonstrates consistent grouping, move to smaller targets and introduce slight variabilities (diffrent lies, wind simulation). Recommended cues include “pick a dot,” “point the face,” and “step parallel”. For practice structure:

- Block practice for initial acquisition (focus on repetition with alignment aids),

- then switch to random practice to promote transfer to on-course variability.

This staged progression, coupled with simple measurable goals (group size, left/right bias), yields the moast reliable improvements in shot accuracy.

Postural Optimization and Core Engagement Techniques to Reduce Injury Risk

Optimal postural alignment and deliberate core activation form the biomechanical foundation for safe, repeatable golf swings. Maintaining a neutral spinal axis and balanced pelvic orientation distributes compressive and shear forces more evenly through the lumbar spine and hips, reducing peak loads that contribute to overuse injuries. Empirical studies in sports biomechanics indicate that athletes who adopt consistent trunk stabilization strategies demonstrate improved energy transfer through the kinetic chain and lower incidence of low-back pain; thus, posture is not merely aesthetic-it is indeed a primary injury-mitigation variable.

Assessment and immediate in-session corrections should use concise, reproducible cues to establish a stable address position. Common, evidence-aligned cues include:

- Neutral pelvis: small anterior tilt until the lumbar lordosis is natural but not exaggerated.

- Long thorax: slight rib-cage-down cue to avoid excessive extension at setup.

- Soft knees: micro-flexion to enable hip-driven rotation versus knee-driven sway.

- Distributed weight: even pressure across metatarsal heads and heels to permit axial rotation.

These cues can be rapidly evaluated using video capture, contact mats, or simple mirror feedback, enabling objective coaching and immediate corrective action.

Targeted core-engagement techniques should be integrated as both warm-up and conditioning modalities. Effective, evidence-based options include the dead-bug for coordinated contralateral limb control, front and side planks for anti-flexion and anti-lateral-flexion endurance, and pallof-presses for anti-rotation capacity. The following table summarizes concise progressions appropriate for novice golfers and usable within a weekly plan:

| Exercise | Purpose | Simple Progression |

|---|---|---|

| Dead-Bug | Coordination & lumbar control | Alternating limbs → resisted band |

| Side Plank | Lateral chain endurance | Knee-supported → full side plank |

| Pallof Press | Anti-rotation stability | Bodyweight → band → cable |

Translation of core work into the swing requires specific drills that preserve spine angle and resist deleterious lateral flexion or early extension. Useful practice progressions include half‑swings with an emphasis on maintaining chest-to-thigh distance, slow‑motion full swings focusing on controlled deceleration through impact, and rotational medicine‑ball throws to reinforce coordinated hip‑torso sequencing. Implementing tactile feedback (e.g., placing a club across the shoulders or using a resistance band anchored at the sternum) further reinforces kinesthetic awareness of trunk position during dynamic movement.

Designing a practical program balances motor control training, progressive strength endurance, and mobility work. Begin with 2-3 sessions per week of short core sessions (10-20 minutes) combined with daily brief mobility routines for thoracic rotation and hip hinge patterning. Progress load by increasing duration,resistance,or task complexity while monitoring pain and swing quality metrics (ball flight consistency,perceived effort). When signs of persistent discomfort or asymmetric movement patterns appear, referral to a physiotherapist or sports medicine professional for individualized assessment is recommended to minimize injury risk while optimizing performance.

swing Path Diagnostics and corrective Drills to Promote Consistent Ball Striking

Accurate diagnosis begins with objective, reproducible measures. Combine high-frame-rate video (face-on and down-the-line), a launch monitor, and tactile feedback tools such as impact tape or foot spray to establish a baseline of where the clubhead travels and where it contacts the ball. Alignment sticks oriented parallel to the intended target and an elevated stick running along the shaft plane allow for rapid visual confirmation of swing plane deviations. Recording before-and-after data is essential: without quantitative comparison, perceived improvements are unreliable.

Interpreting the data requires understanding the clubface-path interaction. Typical novice signatures include an out-to-in path with an open face producing slices, and an in-to-out path with a closed face producing hooks. Ball flight must be read alongside impact location: heel or toe strikes often bias the apparent curvature and mask true path faults. Use synchronized video and launch data-path, face angle, spin axis-to disambiguate whether the primary deficiency is path, face control, or impact position.

Corrective interventions should be specific, simple, and repeatable. Recommended drills include:

- Gate Drill (two tees or headcovers) to enforce a square takeaway and prevent early outside path entry;

- Towel Under Arm to promote synchronized rotation and reduce arm-dominant outside-to-in swings;

- Alignment-Stick Plane (stick along target line and one angled to ideal shaft plane) to grok the desired inside path on the downswing;

- Impact Bag for feel of a square, compressive strike and to shorten the learning feedback loop.

Evidence-based practice structure amplifies drill efficacy. Favor variable and randomized practice schedules once a basic motor pattern is established, and reduce external feedback frequency to foster error detection and retention. Short, high-quality repetitions (sets of 10-20 focused swings with deliberate attentional focus) produce larger long-term gains than prolonged, mindless batting practice. Implement constrained practice (e.g., alternate club lengths, target overlays) to promote adaptable motor solutions rather than brittle, context-dependent fixes.

Use a simple, measurable progression to operationalize training. Below is a practical weekly microcycle that pairs diagnostics with targeted drills and objective metrics to track consistent ball striking.

| Session | Focus | Metric |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Video + Gate Drill | Impact tape center % |

| 2 | Alignment-stick plane work | Path consistency (deg) |

| 3 | Impact bag + launch monitor | clubface at impact (deg) |

Reassess weekly using launch monitor metrics (carry dispersion, spin axis) and synchronized video; adjust drill emphasis when path variance falls below an acceptable threshold. Objective, iterative measurement is the most reliable pathway from sporadic contact to repeatable, consistent ball striking.

Tempo Regulation and Motor Learning Approaches to Develop Reliable Rhythm

Reliable rhythm in the golf swing is not an innate trait but an emergent property of well-structured motor learning. Research from motor control and sport science indicates that tempo regulation reduces variability in timing and improves shot-to-shot consistency by stabilizing intersegmental coordination. Emphasizing **temporal regularity** (e.g., consistent backswing-to-downswing ratio) rather than rigid kinematic templates encourages adaptive control: players who internalize tempo are better able to reproduce effective movement under pressure and transfer skills across clubs and conditions.

Practical prescriptions derived from empirical findings prioritize graduated, representative practice. Use the following evidence-aligned tactics to build dependable rhythm:

- Metronome-paced practice – begin with slow, externally paced beats and gradually increase to match game speed.

- Ratio training – practice consistent timing ratios (commonly 3:1 or 2:1 backswing:downswing) to emphasize sequencing over position.

- Variable practice – alternate clubs, lies and target distances to foster robustness and transfer.

These interventions duplicate critical timing constraints and produce larger retention and transfer effects than repetitive, unvaried drilling.

Augmented feedback and attentional strategies strongly influence tempo learning. Provide **reduced, summary feedback** (e.g.,intermittent outcomes or averaged tempo data) to prevent dependency on external cues. Encourage an **external focus** (e.g., “feel the clubhead swing through the target”) rather than internal kinematic cues to promote automaticity. Where appropriate, integrate quiet-eye stabilization and constrained dual-tasking to accelerate implicit control-these methods help athletes maintain tempo when cognitive load increases during competition.

| Drill | Purpose | Progression |

|---|---|---|

| Metronome sways | Tempo entrainment | Slow → match swing speed |

| Tempo ladder | Rate variability control | 3:1 → 2:1 ratio |

| Dual-task reps | Automaticity under load | Low cognitive → competitive pressure |

| Constraint play | Adaptation & transfer | Change lies/targets |

This curriculum-style mix of drills leverages constraint-led and differential learning principles to shape timing without prescribing rigid joint positions.

Assessment and progression rely on objective measurement and staged overload. monitor key metrics (average tempo ratio, standard deviation of cycle time, and retention scores after 24-72 hours) and use them as criteria for progression: reduce metronome frequency dependence, increase contextual variability, then shift to performance-focused sessions. In practice, maintain a brief log of tempo metrics and perceptual ratings; prioritize **retention and transfer** outcomes over transient performance gains to ensure that improved rhythm endures under real-world conditions.

Ball Positioning relative to Stance and Club Selection: Practical Guidelines for Improved Contact

Ball placement governs the geometry of contact: shifting the ball forward or back in the stance changes the club’s interaction with the turf, the effective loft at impact, and the desired angle of attack. Empirical studies and high-speed video analyses indicate that even modest changes (one ball-width) modify spin rates and launch angles. For novices, adopting a reproducible reference point relative to the feet is more useful than guessing: relate the ball to a fixed anatomical landmark (e.g., inside of the lead heel for mid-irons) and maintain consistency across practice repetitions.

Practical mapping between clubs and position simplifies decision-making on the range and course. The table below summarizes conventional, evidence-aligned recommendations for common clubs; use it as a baseline and adjust for individual swing tendencies (steeper vs. sweeping) and ball-flight goals.

| Club | Relative Ball Position | Contact Intent |

|---|---|---|

| Driver/Fairway Wood | Off front heel | Sweep up, higher launch |

| mid-Irons (5-7) | Center to slightly forward of center | Compressed, moderate descent |

| Short Irons/Wedges | Back of center to slightly back | Steeper descent, solid turf interaction |

Incorrect placement produces characteristic contact faults. A ball too far forward on short irons encourages thin or topped shots as the club is still rising; too far back on long clubs produces hooks and loss of distance due to early ground contact.To remediate these issues, implement simple checks: mirror your normal stance and note where the ball aligns to the lead foot, measure relative to a consistent marker on the shoe, and record a few swings on video to confirm impact point. Consistency of reference outperforms arbitrary adjustments.

Club selection and ball position are co-dependent variables: longer shafts require more forward ball positions and a flatter attack angle, while shorter clubs demand a more central or rearward ball and a steeper, descending strike. Biomechanically,the center of rotation of the torso and the desired shaft lean at impact dictate where the ball should sit. When selecting clubs for varied lies or wind conditions,prioritize how that combination will alter your intended angle of attack and adjust ball placement by small increments rather than wholesale changes.

transfer improvements into the practice routine with targeted drills and measurable feedback:

- Line-Alignment Drill: place a club or alignment stick on the ground and position the ball relative to the same foot landmark until repetition error is within one ball-width.

- Tee Height & Ball-forward Drill: use a low tee to train sweep with long clubs; progressively lower tee height for mid-irons to encourage compression.

- progressive Club Sequence: hit a set of shots moving from wedges through driver, checking that ball position shifts incrementally and produces predictable contact.

Use video capture or impact tape to quantify change; regular, small adjustments informed by objective feedback yield faster improvements in contact quality than sporadic, large positional changes.

Short Game Fundamentals and Evidence Based Practices for Chipping, pitching, and Putting

Effective short-game competence rests on a small set of reproducible objectives: consistent contact, controlled launch/spin, and reliable distance control. contact governs whether shots run or spin; launch/spin determine trajectory and stopping; and distance control governs proximity to the hole. Translating these objectives into practice requires isolating mechanical variables (setup, clubface, stroke) and coupling them with perceptual tasks (green reading, landing-spot selection). Adopting an evidence-oriented framework-define the target metric, choose drills that isolate the causal variable, measure performance, and iterate-improves transfer from range to course performance.

For shots around the green that run more than they fly, emphasize a narrow, forward-weighted setup and a firm lower body to stabilize impact. Use a slightly back-ball position for low-running chips and a more central position for higher-trajectory bump-and-runs. Common novice errors and concise remedies include:

- Excessive wrist hinge: shorten the stroke and feel a locked lead wrist through impact to improve consistency.

- Incorrect club selection: choose loft to control spin and trajectory; practice the same landing spot with multiple clubs to learn carry vs roll behavior.

- Unstable base: adopt a narrow,athletic stance with 60-70% weight on the front foot to promote clean turf interaction.

These adjustments prioritize repeatable impact conditions-an outcome repeatedly found to reduce distance error and improve proximity-to-hole metrics.

Pitching requires controlled loft change and planned landing zones; mechanical emphasis should be on tempo, hinge depth, and acceleration through the shot. Recommended practice drills include a controlled landing-spot drill (aim for a specific patch of turf),a towel-under-the-arms drill to promote synchronous arm-body movement,and a half-swing-to-full-swing progression to stabilize tempo. the following compact table aligns drills with measurable practice targets:

| Drill | Purpose | Target |

|---|---|---|

| Landing-Spot Drill | Control carry and spin | 8/10 inside target |

| Towel Under Arms | Synchronize shoulders and arms | Smooth,repeatable swings |

| Half-to-Full Progression | Stabilize tempo and swing length | Consistent distance gaps |

Putting success is primarily a function of distance control and green-reading accuracy. Biomechanically, stable lower body, minimal wrist action, and a consistent pendulum stroke produce superior repeatability. Evidence-based practices include:

- Tempo training: use a metronome or three-count rhythm to standardize backstroke and follow-through durations.

- Speed-first drills: practice long, target-less strokes to calibrate feel for green speed before adding aim tasks.

- Visual landing markers: pick a spot short of the hole as a primary cue to translate perceived speed into stroke length.

Combine these with routine video capture of the stroke and simple metrics (e.g., percentage of putts ending within 3 ft) to track objective improvement.

Design practice around variability and feedback: alternate block practice to ingrain mechanics with random practice to build adaptability under pressure, and integrate immediate augmented feedback (video, launch monitor, or simple proximity measurement). Weekly allocation can be brief but focused-high-frequency short sessions outperform less frequent marathon practices for motor learning. Suggested weekly micro-plan:

- Chipping: 3 sessions × 20 minutes (landing-spot focus)

- Pitching: 2 sessions × 25 minutes (distance bands and towel drill)

- Putting: 4 sessions × 15-20 minutes (tempo and speed calibration)

Track progress with simple performance indicators-mean distance from hole on chips/pitches and putts made from 3-10 ft-and iterate technique and drill selection when metrics plateau.

Q&A

Q: What does the term “novice” mean in the context of this article?

A: In this context, “novice” denotes a beginner or someone recently introduced to golf who lacks ample experience or domain-specific skill (i.e., a person who has only been doing the activity for a short time). Lexicographic sources define “novice” as an inexperienced person or beginner (see Collins; American Heritage; Merriam‑Webster; Dictionary.com).

Q: Which eight errors commonly appear among novice golfers?

A: The eight common errors addressed are: (1) improper grip, (2) unstable or incorrect stance, (3) poor alignment, (4) faulty posture, (5) incorrect swing path, (6) inconsistent tempo, (7) incorrect ball position, and (8) inadequate short‑game technique (chipping and pitching).

Q: Why focus on these eight errors?

A: These errors are basic determinants of ball flight, distance control, and injury risk. They are prevalent in early learning stages because they involve basic motor patterns, body positioning, and perceptual judgments.correcting them yields disproportionately large performance improvements and reduces compensatory movements that can lead to injury.Q: For each error, what is the problem, why it matters (mechanistically), and what evidence‑based corrective strategy should a coach or learner use?

1) Grip

– Problem: Too weak/strong, inconsistent hand placement, or excessive tension.

– why it matters: Grip determines clubface orientation and influences wrist hinge and release patterns; excessive tension reduces clubhead speed and timing consistency.

– evidence‑based fixes:

– Use an objective reference: mark consistent grip positions relative to the shaft (e.g., knuckle count or measured overlap/interlock).

– Train relaxation: progressive tension drills (grip-and-relax repetitions) and breathing cues during address reduce over‑grip.

– Motor learning approach: variable‑practice drills with different grips to build adaptability; augmented feedback (video or mirror) to show consistent hand placement.

– Measurement/progression: monitor shot dispersion and clubface angle at impact with launch monitor or high‑speed video; aim for reduced left/right dispersion and consistent face orientation.

2) Stance

– Problem: Feet too narrow/wide, unstable base, knees locked.

– why it matters: Stance affects balance, weight transfer, and ability to rotate; instability yields compensatory lateral movements and inconsistent strikes.

– Evidence‑based fixes:

– Adopt sport‑specific base: hip‑width stance for irons,slightly wider for long clubs; slight knee flex to permit dynamic rotation.

– Balance drills: slow‑motion swings, single‑leg balance progressions, and foam‑pad work to improve proprioception.

– Constraint‑based training: narrow-to-wide stance progressions to find effective base for individual anthropometry.- Measurement/progression: track Center of Pressure shifts (or subjective balance rating), consistency of contact (divots pattern), and shot quality.

3) Alignment

– Problem: Body aimed left or right of intended target; inconsistent alignment.

– Why it matters: Misalignment causes compensatory swing path and poor directional control.

– Evidence‑based fixes:

– Use external references: alignment sticks/club laid on ground during practice to train parallel setup to target line.

– Pre‑shot routine: consistent step behind/inside-line check to reduce perceptual bias.

– Perceptual training: mirror checks and video feedback to reconcile visual aiming versus actual body orientation.

– Measurement/progression: measure deviation between intended and actual ball flight; reduce consistent directional bias.

4) Posture

– Problem: Excessive bending from the waist, too upright, or rounded shoulders.

– Why it matters: Poor posture restricts hip/torso rotation and leads to inconsistent swing plane and loss of power.

– evidence‑based fixes:

– Structural check: hinge from hips with neutral spine and slight knee flex; maintain chest over ball.

– Drill: “stick down the back” or alignment‑pole against spine to train neutral posture; slow dead‑lift posture drills to train hip hinge.

– Progressive loading: medicine‑ball rotational drills to build functional core strength and posture endurance.

– Measurement/progression: observe rotational range, ball compression, and clubhead speed; fewer thin/top shots as posture stabilizes.

5) Swing path

– Problem: Over‑outside‑in (slice) or excessively inside‑out (hook) paths; inconsistent plane.- why it matters: Swing path relative to clubface orientation determines side spin and curvature of flight.

– Evidence‑based fixes:

– Video/Motion analysis: identify path errors using slow‑motion or launch monitor data.- Targeted drills: gate drills (two tees/sticks) encouraging a correct entry and exit path; impact bag work to feel square impact.

– Motor learning principles: blocked practice to ingrain the correct path followed by variable practice to generalize.

– Measurement/progression: use ball flight and spin metrics to assess reduction in side spin and curvature.

6) Tempo

– Problem: Rushed backswing, jerky transition, or variable timing.

– Why it matters: Tempo coordinates sequencing of body segments, affecting timing of impact and energy transfer.

– Evidence‑based fixes:

– Metronome training: practice swings to an auditory rhythm to stabilize backswing/downswing timing.

– Segmental sequencing drills: pause-at-top and accelerate drills to train consistent transition timing.

– Feedback and retention: incorporate both external focus (target) and internal timing cues to consolidate tempo patterns.

– Measurement/progression: measure variability in swing time and consistency of contact; improved distance consistency is expected.7) Ball position

– Problem: Ball too far forward/back in stance relative to club choice; inconsistent positioning.

– Why it matters: Ball position influences low point, strike location, and angle of attack; incorrect position causes fat/thin shots or needless spin.

– Evidence‑based fixes:

– Rule‑based placement: teach normative ball positions (e.g., center for short irons, slightly forward of center for mid‑irons, ball forward of center for driver) tailored to player height and swing arc.

– Visual cues and tee markers: train consistent setup with club‑on‑ground reference or tape marks on range mat.- Impact drills: half‑swings focusing on compression for irons to reinforce correct low point relative to the ball.

– Measurement/progression: track ground contact patterns and launch monitor data to ensure consistent attack angles.

8) Short game

– Problem: Poor chipping/pitching technique, inadequate distance control around the green.

– Why it matters: Short game accounts for a large proportion of strokes; inefficiencies here limit scoring even if long game improves.

– Evidence‑based fixes:

– Simplify mechanics: adopt a basic low‑or‑high loft strategy (hands ahead for chips, neutral for pitches) with consistent ball position and narrow stance.

– Distance control drills: ladder drills (land marks at set distances), bump‑and‑run practice, and tempo work with a metronome to calibrate feel.

– Deliberate practice structure: short,frequent sessions focusing on purposeful repetition and immediate feedback (ball flight,landing spot).

– Measurement/progression: measure up-and-down conversion rates, proximity to hole on pitches/chips, and number of putts per hole.

Q: What types of evidence underpin these corrective strategies?

A: the recommendations synthesize findings from applied motor learning, biomechanics, coaching science, and skill acquisition literature.Evidence types include biomechanical analyses (motion capture, force plate), perceptual‑motor studies demonstrating variability and contextual interference effects, coaching intervention studies (skill‑acquisition protocols), and practical field data (launch monitors, performance outcomes). While randomized controlled trials in golf technique are limited, convergent evidence from these methodologies supports the listed interventions.

Q: How should practice be structured to maximize learning and transfer?

A: Use evidence‑based practice design:

– begin with blocked practice for initial skill acquisition (consistent repetitions of the target movement).

– Progress to variable and contextual practice (different lies,targets,clubs) to promote adaptability and transfer.

– Provide a mixture of intrinsic feedback (ball flight) and augmented feedback (video, launch monitor) with faded frequency to avoid dependence.

– integrate deliberate practice: short, focused sessions with specific goals and measured outcomes.

– Include rest and recovery; distributed practice typically outperforms massed practice for retention.

Q: How can a novice measure progress objectively?

A: Use measurable outcome metrics:

– Ball flight (direction, carry, dispersion) and spin metrics from launch monitors.

– Proximity to hole on approach and short game (greens in regulation, up‑and‑down percentage).

– Kinematic measures where available: clubhead speed, attack angle, face angle at impact (via sensors or video).- Simple field measures: shot grouping, reduction in miss bias (consistent left/right), and consistency in contact (fewer fat/top shots).

Q: What role should a coach or technology play?

A: Coaches provide diagnostic expertise, individualized cueing, and structured progression. Technology (high‑speed video, launch monitors, wearable sensors) supplies objective feedback that accelerates learning when interpreted appropriately. Best practice pairs coach judgment with objective data to design interventions tailored to the learner’s anthropometry, physical capacity, and learning preferences.

Q: Are there safety considerations when fixing technical faults?

A: Yes. Correcting technique should consider joint loading, existing musculoskeletal limitations, and fatigue. Emphasize:

– Gradual progression of swing speed and load.- Core and hip mobility/strength training before aggressive swing changes.

– Avoiding excessive overswing or forced movements that strain the lower back or wrists.- Referral to medical/physiotherapy professionals if pain occurs.

Q: When should a novice seek professional instruction?

A: Seek coaching when:

– Technical faults persist after self‑directed practice and simple drills.- Consistent pain or discomfort occurs.

– The learner requires a structured progression or individualized program,especially if plateaus are reached.

– Objective data (launch monitor or video) suggests complex kinematic issues beyond self‑correction.

Q: What are practical next steps for a novice reader who wants to apply these fixes?

A: Recommended plan:

1. Conduct a baseline assessment (short video of address and swing, set of representative shots).

2. prioritize one or two faults (start with grip and posture/alignment), using simple drills and external references (sticks, video).

3. Structure short, frequent practice sessions with focused goals and feedback.

4. Introduce variability after basic consistency is achieved.

5. Reassess every 4-6 weeks using objective measures or coach evaluation to iterate adjustments.

Q: Limitations and caveats of the guidance

A: Individual variability (anthropometry, versatility, prior motor experience) means there is no one‑size‑fits‑all solution. Evidence is strongest for general motor learning principles and biomechanical relationships; specific technical cues may require tailoring. Novices should balance technical correction with fun and engagement to maintain motivation.

If you would like, I can convert this Q&A into a printable handout, create a week‑by‑week practice plan based on these corrections, or produce short video/demo cue scripts for each corrective drill.

Key Takeaways

Conclusion

This review has identified eight recurrent errors among novice golfers-grip, stance, alignment, posture, swing path, tempo, ball position, and short-game technique-and synthesized evidence-based interventions that target the motor, biomechanical, and perceptual contributors to those faults. recognizing that a “novice” is, by definition, a learner with limited experience, the corrective approaches emphasized here prioritize clear, incremental instruction, structured practice, and objective feedback to accelerate skill acquisition while reducing injury risk.

Practically, coaches and learners should adopt a focused, phased strategy: assess and prioritize the one or two errors that most constrain performance; apply simple, empirically supported drills and external-focus cues; use variable and task-relevant practice to promote transfer; incorporate basic physical conditioning where necessary; and employ video or coach feedback for timely error correction. Safety and progressive overload-both in technical complexity and practice volume-should guide every intervention.

For researchers and practitioners, continued evaluation of training dose, cueing strategies, and technology-enabled feedback in novice populations remains a priority. Longitudinal and controlled studies that link specific instructional methods to measurable changes in performance and injury incidence will strengthen the evidence base and refine best practices.

By combining principled, evidence-based techniques with patient, systematic practice and regular reassessment, novices can make reliable, sustainable improvements.The pathway from beginner errors to competent, resilient play is deliberate and teachable-an outcome attainable through informed instruction, careful practice design, and ongoing evaluation.

Eight Common Novice Golf Mistakes and Evidence-Based Fixes

how to read this guide

This article breaks each common novice mistake into three quick parts: the problem, an evidence-based corrective strategy, and practical drills you can use on the range or practice green. Use the headings to jump to problems you want to fix (e.g., grip, swing path, short game).

1. Weak or inconsistent golf grip

Problem

A poor grip causes inconsistent clubface control, leading to slices, hooks, and unpredictable shots. Common beginner grip errors include gripping too tight, too weak (hands too much on top of the handle), or inconsistent hand placement across clubs.

Evidence-based fix

- Adopt a neutral grip: Vardon (overlapping) or interlock are both acceptable-focus on consistent hand placement and showing 2-3 knuckles on the lead hand at address.

- Grip pressure: research from coaching consensus and biomechanics suggests light-to-moderate grip pressure (score ~4-6/10) preserves wrist hinge and clubhead speed while improving feel and control.

- Face control: your grip should allow you to square the clubface at impact; small wrist adjustments impart large face changes, so consistency matters.

drill – Towel under hands: Place a folded towel under both palms and grip the club. This forces correct wrist angles and reduces choking the club. Practice half and full swings.

2. Poor stance and base of support

Problem

Too narrow or too wide a stance reduces balance and power. Novice golfers often stand too upright or with weight too far on their toes or heels, upsetting the swing arc and rotation.

Evidence-based fix

- Stance width: for irons, feet shoulder-width apart; for driver, slightly wider. This gives a stable base for rotation.

- Weight distribution: start with ~50/50 weight distribution, flex the knees slightly and feel balanced over the mid-foot.

- Dynamic balance: drills that challenge balance (e.g., single-leg or wobble-board) improve proprioception and swing consistency per motor-learning principles.

Drill – Rock test: Address a mid-iron and slowly rock forward onto toes and back onto heels while maintaining spine angle. If you can maintain position, your stance is stable.

3. Misalignment (aiming errors)

Problem

Many beginners aim their body left or right of the target without realizing it, then compensate with poor swing path to “fix” the shot-this compounds errors.

Evidence-based fix

- Use alignment aids: alignment sticks or a club on the ground to confirm target line and foot line are parallel.

- Pre-shot routine: pick an intermediate target (a blade of grass or leaf) 6-10 feet in front of the ball to line up and maintain focus-this simple visual cue greatly improves alignment consistency.

Drill – Two-stick alignment: Place one stick pointing at the target and another parallel to your toes. Practice 10 balls ensuring the clubface and feet are square to the target stick.

4. Bad posture and spine angle

Problem

Slouching, rounded shoulders, or standing too tall changes the swing arc and can lead to fat or thin shots and back strain.

Evidence-based fix

- Neutral spine: hinge from hips with a slight knee flex; chest over or slightly ahead of the ball for irons. Maintain the same spine angle throughout the swing.

- Mobility matters: basic thoracic rotation and hip mobility exercises reduce compensation and allow safer, more powerful swings.

Drill – Wall tilt: Stand with your back a few inches from a wall and hinge at the hips keeping the spine long. hit short swings while keeping a consistent distance to the wall.

5. Incorrect swing path (outside-in or inside-out extremes)

Problem

Outside-in paths often produce slices; extreme inside-out paths can create hooks. Many novices swing across the ball rather than along the intended target line.

Evidence-based fix

- Work on swing-plane awareness with video feedback-players who view their swings improve faster per motor learning literature because visual feedback accelerates error correction.

- Use gate and plane drills: set up guides to encourage the desired path (slight inside-to-square-to-inside for a drawable neutral shot).

Drill – Alignment gate: Put two tees or sticks on the ground forming a “tunnel” slightly inside the target line. Swing without hitting the sticks to reinforce proper path.

6. Poor tempo and rushing the swing

Problem

Beginners often try to hit the ball hard and speed up the downswing. This disrupts sequencing, reduces control and increases injury risk.

Evidence-based fix

- Adopt a consistent tempo: many coaches recommend a 3:1 backswing-to-downswing rhythm or use a metronome to find and lock in a repeatable tempo.

- Sequencing: focus on turning the torso and initiating the downswing from hips (proximal-to-distal sequencing). Proper sequence increases clubhead speed efficiently and reduces strain.

Drill – Metronome swing: Use a metronome app set to an even beat. Start the backswing on beat 1, start the downswing on beat 4. Practice 20 swings at reduced intensity.

7. Incorrect ball position

Problem

Ball too far forward or back in the stance causes thin, fat, or misfired impact.Different clubs require slightly different ball positions.

Evidence-based fix

- General rule: shorter clubs (wedges, short irons) – middle of stance; mid/long irons – slightly forward of center; driver – off the inside of the lead heel.

- adjust for shaft length and swing arc: long clubs need more forward position for an upward strike; mid-irons need to strike down slightly.

Drill – Impact tape check: Use impact tape or spray to check strike location and adjust ball position until you consistently hit the sweet spot.

8.Weak short game (chipping & putting)

Problem

Beginners often neglect the short game or overcomplicate it. Poor technique around the green causes unnecessary strokes and frustration.

evidence-based fix

- putting fundamentals: consistent setup, minimal wrist action, and a steady stroke length are backed by putting studies that link repeatability to performance.

- Chipping basics: use a narrow stance,weight slightly forward (60/40),hands ahead of the ball,and play the ball back in the stance for crisp contact.

- Practice structure: short, focused sessions on the putting green (block practice for feel; random practice for decision-making) produce better retention and on-course performance.

Drill – Clock drill (putting): Place balls at 3, 6, 9 and 12 feet around the hole; make 12 in a row. This builds distance control and pressure handling.

Quick reference table: Problem → Fix → Drill

| Problem | Fix | Simple Drill |

|---|---|---|

| Grip | Neutral, light pressure | Towel under hands |

| Stance | Shoulder-width, balanced | Rock test |

| Alignment | Use target stick | Two-stick alignment |

| Posture | Hip hinge, long spine | Wall tilt |

| Swing path | Plane awareness | Alignment gate |

| Tempo | 3:1 rhythm, metronome | Metronome swing |

| Ball position | Adjust per club | Impact tape check |

| Short game | Setup & distance control | Clock drill |

Additional practical tips for faster improvement

- Video your swing from two angles (face-on and down-the-line). Visual feedback accelerates motor learning and helps identify posture, swing path and timing issues.

- Prioritize quality practice: short, focused sessions with a specific goal and measurable outcome beat long, unfocused range time.

- Get periodic coaching: even a few sessions with a PGA coach or certified instructor (e.g., TPI-certified) provides targeted cues and prevents ingraining bad habits.

- Include mobility and strength basics: simple hip and thoracic mobility work plus core stability reduces injury risk and supports better rotation and balance.

- Use on-course practice: practice under pressure with scorekeeping or games to transfer range improvements to real rounds.

Case study snapshot – Two-week practice plan for beginners

Follow this 2-week micro-plan (3 sessions/week,45 minutes each) to attack several common faults in a structured way:

- Session A (Range): 10 min warm-up + 15 min alignment & ball position drills + 15 min swing path work with gate + 5 min notes/video.

- Session B (Short game): 20 min chipping set-up & strike practice + 15 min putting clock drill + 10 min pressure games.

- Session C (tempo & balance): 10 min mobility + 20 min metronome swings + 15 min balance drills and impact checks.

Benefits of fixing these novice errors

- Lower scores: improved contact, alignment and short game directly translate to fewer strokes.

- Consistency and confidence: repeatable fundamentals reduce round-to-round variance.

- Reduced injury risk: better posture and sequencing protect the lower back and wrists.

- Faster improvement: targeted, evidence-based drills accelerate skill acquisition compared with random practice.

Resources and next steps

Track progress with short videos,a practice journal,and simple objective metrics (e.g., fairways hit, greens in regulation, putts per round).If you find a persistent problem, consider a lesson with a certified coach who can use launch monitors and motion analysis to create a tailored plan.

Pro tip: Small, consistent changes beat big swings in technique. Pick one error to fix at a time and practice deliberately.