golf’s Historical Evolution: Rules, Courses, Society

Introduction

Golf occupies a singular place among modern sports as both a deeply traditional pastime and a continually evolving cultural practice. Tracing its lineage from rudimentary forms of stick-and-ball play in late medieval Scotland to a globally organized industry, golf provides a rich site for historical inquiry into how rules, physical environments, and social structures co‑constitute sporting life. This article examines the sport’s long-term development through three interlinked axes-rules and governance, course design and landscape, and the social forces that have shaped participation and meaning-arguing that each axis has repeatedly mediated tensions between preservation and change.

First, the codification of rules and the establishment of governing bodies-most notably the Royal and Ancient Golf Club of St Andrews and the United States Golf Association-transformed localized customs into standardized practices, enabling competition across regions and eras while together embedding particular values and norms. Second, shifts in course architecture-from windswept links to manicured parklands and technologically engineered modern layouts-reflect changing aesthetics, ecological understandings, and commercial imperatives; designers and clubs have negotiated the interplay of terrain, technology, and playability to produce landscapes that are both cultural artifacts and performance spaces. Third, social transformations-industrialization and urbanization, patterns of class and gender exclusion and inclusion, colonial diffusion, and the later democratizing effects of mass media and leisure economies-have continually redefined who plays golf, how it is indeed consumed, and what it signifies.

Methodologically,this study synthesizes archival sources,contemporary rulebooks,design plans,and secondary literature to situate golf within broader histories of sport,landscape,and modernity. The following sections chart the chronology of rule formation, analyze seminal developments in course design and architecture, and interrogate social dynamics that have preserved traditions even as the sport adapts to technological, economic, and cultural change. By articulating these dimensions in tandem, the article seeks to illuminate how golf’s enduring traditions are both products and producers of historical processes.

Note: The brief web results provided with the query contained contemporary forum and equipment postings rather than primary historical or academic sources; the analysis below thus relies on established historiography and archival materials pertinent to the subject.

Origins and Early Codification of Golf Rules: Historical Trajectories and Recommendations for Archival standardization

Scholarly examination situates golf’s genesis in late-medieval Scotland, where references to stick-and-ball play appear in municipal records and royal proclamations (notably the 1457 prohibition by James II). Early practice was a vernacular, landscape-driven pastime rather than a codified sport: play adapted to linkslands, communal fairways and local customs. The gradual shift from customary play to written regulation reflects broader processes of modernization-urbanization, printing, and club institutionalization-rather than a single origin point. Primary sources from the period (municipal ordinances, early scorecards, and the 1744 rules of the gentlemen Golfers of Leith) demonstrate an incremental movement toward formalization rooted in local needs and social prestige.

codification accelerated in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries through the agency of clubs and associations that sought to resolve disputes and standardize competition. The foundation of the Royal and Ancient Golf Club of St Andrews (1754) and the later establishment of the United States Golf Association (1894) signaled institutional commitment to uniform rules. Early rule-writing addressed immediate practicalities-teeing, hole definition, hazards and ball replacement-yet also encoded values about sportsmanship and class. Comparative analysis of editions of the rules shows iterative refinement: language tightened, penalties standardized, and interpretive guidance expanded, producing a corpus that both regulated play and reflected shifting material conditions such as new ball and club technologies.

From a historiographical perspective, the trajectory of rule development must be read alongside material change and imperial diffusion. Technological innovations (gutty and rubber-core balls, steel shafts) repeatedly forced rule-makers to reassess fairness and safety; colonial and transatlantic networks then transmitted British regulatory models while producing local variants. Consequently, surviving documentary evidence is heterogenous: club minute books, printed rule pamphlets, match reports in the press, photographic records, and players’ diaries each capture different registers of meaning. This plurality poses both opportunity and challenge for scholars seeking coherent genealogies of rule change and social practice.

For durable and interoperable preservation, archives should adopt disciplined, transparent standards that foreground provenance, context, and machine-readability. Recommended measures include standardized metadata using adapted schemas (e.g., Dublin Core with sports-history extensions), long-term master files (TIFF or lossless formats), and linked-data identifiers for persons, clubs, and courses. Best practices emphasize distributed digitization, controlled vocabularies, and versioning of rule texts to preserve editorial histories. Practical steps:

- Capture provenance: retain original order and custody notes.

- Digitize at acquisition: high-resolution masters + searchable derivatives.

- Apply persistent identifiers: DOIs or ARKs for key documents and rule editions.

- Document transformations: record OCR corrections, transcriptions, and editorial emendations.

| Metadata Field | Purpose | Recommended Format |

|---|---|---|

| Title | Identifies document/rule edition | Transcribed string |

| Date | Temporal context of enactment | ISO 8601 |

| Provenance | Original custody and source notes | Free text + controlled URI |

| Version/Edition | Tracks revisions and rule lineage | Structured string (e.g., v.1744-1) |

| Related Entities | People,clubs,courses referenced | Controlled vocabulary/URI list |

The Emergence of the Eighteen Hole Convention: Evidence,Debates,and Policy implications for Course Management

Primary documentary evidence for the convention shows a gradual,path-dependent consolidation rather than a single prescriptive decree. Surviving scorecards, club minutes, and early tournament bylaws from scottish and English clubs reveal a transition from highly variable hole counts to a recurrent pattern clustering at eighteen.This convergence is best understood as an emergent institutional outcome: local practices, economic calculations, and competitive exigencies interacted across clubs and governing bodies to produce a widely accepted norm. **Archival heterogeneity**, thus, is itself evidence of process-showing how distributed decision-making produced a durable standard.

scholarly debate has focused on which causal mechanisms were decisive. Competing explanations emphasize (a) institutional authority and codification by influential clubs and associations; (b) practical constraints of land tenure and maintenance; and (c) the social and commercial incentives of tournaments and membership expectations. Key vectors include:

- Institutional signaling: prominent clubs served as behavioral anchors for lesser clubs;

- Economic optimization: eighteen holes balanced playing time against upkeep costs;

- Competitive standardization: tournaments fostered common expectations for fairness and scheduling.

Quantitative analyses and managerial records support these qualitative claims by showing mesoscale patterns-typical round duration, staffing cycles, and land-use footprints-that favor eighteen-hole layouts under certain conditions. The table below summarizes illustrative operational contrasts used in course-management literature (values indicative rather than exhaustive):

| Metric | 9‑Hole Variant | 18‑Hole Standard |

|---|---|---|

| Average Play Time | 1.5 hours | 3.5-4.5 hours |

| Weekly Greens Maintenance | 3-4 days | 5-6 days |

| Typical Land Area | ~30-60 acres | ~100-200 acres |

For contemporary course managers, the historical emergence of the eighteen-hole convention implies concrete policy choices rather than immutable mandates. **Policy instruments** can be configured to reconcile historical norms with contemporary constraints: adaptive tee-time scheduling,rotational maintenance regimes,and modular routing that allows 9‑hole loops to serve multiple constituencies. Recommended operational responses include

- Dynamic scheduling: variable tee-time density aligned to demand peaks;

- Resource zoning: differential maintenance intensity by function (practice,competition,leisure);

- Format flexibility: sanctioned shorter-loop competitions to preserve access while reducing footprint.

Looking forward, debates will center on whether the eighteen-hole model remains the optimal default in diverse socio-environmental contexts. Climate pressures, urban land scarcity, and shifting participation patterns create conditions for renewed experimentation. Management policy should therefore be **evidence-based** and **adaptive**, privileging systems that allow emergent solutions-such as hybrid 9/18 routing, variable pars, and multi-use green corridors-to evolve in response to empirical monitoring and stakeholder negotiation.

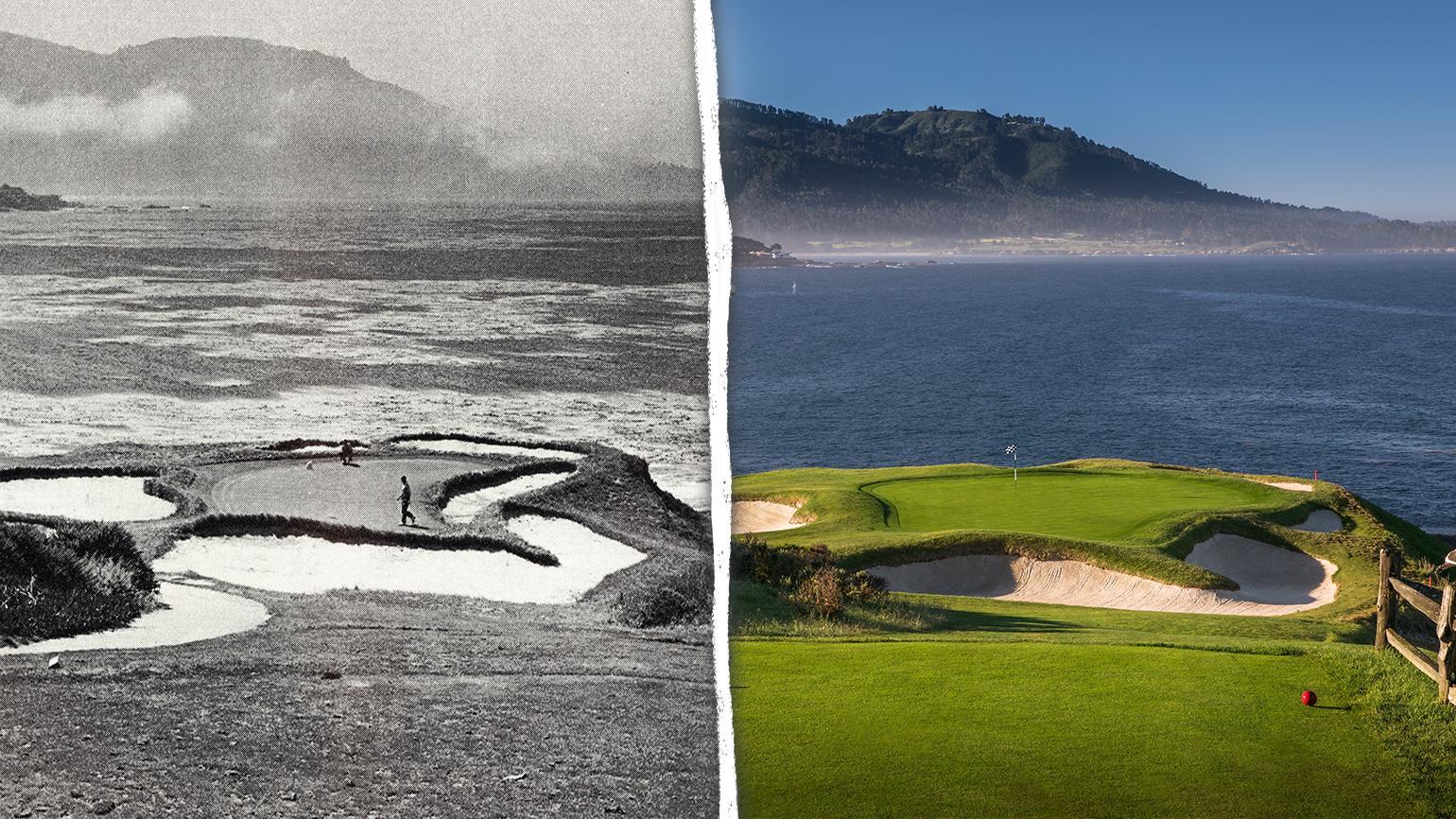

Evolution of Course Design: Landscape Transformation, Strategic Architecture, and Guidelines for Sustainable Restoration

Over the last two centuries golf routing shifted from opportunistic use of natural coastal links to deliberately sculpted inland landscapes, driven by advances in earthmoving, irrigation, and agronomy. Early designers exploited existing dunes and winds; later architects embraced contouring and drainage engineering to create controlled playing corridors.These interventions enhanced year‑round playability but also demanded a rigorous approach to soil conservation and micro‑climate management.The result is a continuum of site manipulation that privileges both strategic diversity and operational resilience.

Contemporary strategic design emphasizes the orchestration of choices presented to the player rather than the imposition of a single line of play. Careful placement of hazards, shaping of fairways, and articulation of green complexes generate a matrix of risk and reward that tests decision‑making across skill levels. By prioritizing spatial sequencing and visual cues, architects create holes that require genuine shot selection, where club choice, angle of approach, and anticipated roll converge to define scoring outcomes.

Sustainable restoration now occupies a central role in design practice, integrating ecological science with playability objectives. Key conservation principles include:

- Water stewardship – reducing potable water reliance via native species, efficient irrigation, and reclaimed sources.

- Biodiversity integration – restoring native habitats and corridors to support pollinators and wildlife.

- Soil and turf health – employing soil amelioration and species-appropriate turf systems to minimize inputs.

- Adaptive maintenance – using monitoring data to refine mowing regimes, fertilization, and pest management.

Practical restoration is iterative and data driven: thorough site assessment, geomorphological analysis, and phased implementation reduce risk and preserve cultural features. Modern tools-LiDAR mapping, GIS hydrological models, and turf performance sensors-enable precise interventions that restore function while safeguarding play characteristics. The table below summarizes typical phases, analytical tools, and expected outcomes in a restoration program.

| Phase | Tool | Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| Assessment | LiDAR / Soil survey | Baseline constraints |

| Design | GIS modeling | Optimized routing |

| Implementation | Phased construction | Minimized disturbance |

| Monitoring | Performance sensors | Adaptive tweaks |

Ultimately, reconciling heritage values with contemporary performance and environmental imperatives requires stakeholder engagement and clear metrics for success. Preservation of classic shot‑values should be balanced with modern expectations for pace of play and resource efficiency. When architects embed measurable objectives-reduced water use, enhanced biodiversity indices, and maintained competitive integrity-the restored landscape becomes both a living archive and a tested arena for future generations of play.

Technological Transformations in Clubs and Balls: Performance, Regulation, and Recommendations for Equipment Governance

Advances in club and ball technologies since the mid-20th century have produced measurable shifts in performance characteristics that challenge traditional conceptions of skill and course design.The replacement of persimmon with metal and composite clubheads, the advent of cavity-back irons, and the refinement of shaft materials have collectively increased **ball speed**, **MOI (moment of inertia)**, and hit dispersion characteristics. These material and geometric innovations yield both increased distance and greater forgiveness, altering shot-selection calculus and necessitating reconsideration of competitive equity across varied playing conditions.

Ball construction has undergone parallel, if not more rapid, transformation: multi-layer cores, advanced urethane covers, and precision-engineered dimple geometries now permit finer control of **spin**, **launch angle**, and aerodynamic stability. Empirical studies demonstrate that modest changes in dimple topology or core hardness produce non-linear effects on carry and rollout, particularly when interacting with modern club faces. Consequently, the equipment pairing-club design and ball specification-must be treated as an integrated system when assessing on-course outcomes and player performance metrics.

Regulatory frameworks instituted by governing authorities have sought to reconcile innovation with competitive fairness. Conformance standards emphasize measurable parameters-ball velocity limits, clubface **coefficient of restitution (COR)**, clubhead dimensions, and testing under prescribed conditions-to contain technology-driven distance escalation. Nonetheless, enforcement faces methodological and jurisdictional limitations: test protocols must be sufficiently reproducible, accessible to manufacturers of all sizes, and adaptable to emergent materials science without introducing undue regulatory lag.

- Standardize transparent testing: mandate public, peer-reviewed test protocols for COR, initial ball velocity, and dimple performance to improve reproducibility and industry compliance.

- Adopt phased thresholds: Use incremental performance ceilings with scheduled reviews to allow manufacturers time to innovate within predictable bounds, reducing disruptive market swings.

- Prioritize accessibility: Consider cost and availability in equipment rules to prevent socioeconomic stratification of play and ensure grassroots participation remains viable.

- Incentivize sustainability: Integrate environmental criteria (material recyclability, lifecycle impact) into conformity assessments to align technological progress with long-term stewardship.

Policy implementation should be informed by concise, comparative metrics that clarify the practical effects of technological change. A compact reference table assists policymakers and course architects in visualizing trade-offs between historical baselines and modern thresholds, facilitating evidence-based decisions about tee placement, course length, and tournament conditions.

| Metric | Historical Baseline | Contemporary Threshold |

|---|---|---|

| Club COR | ~0.82 | ≤0.83 (regulated) |

| Ball Initial Velocity | Lower, single-core designs | Engineered multi-layer target |

| MOI / Forgiveness | Low (wooden era) | High (composite designs) |

Professionalization and Institutionalization of the Game: The Rise of Governing Bodies, Competitive Structures, and Best Practices for Governance Transparency

Institutional consolidation transformed golf from a pastime into a regulated profession. National and international authorities established consistent rulebooks, standardized equipment approvals and adjudication procedures, embedding legalistic norms into everyday play and tournament administration.

Formal competitive architectures-professional tours, amateur circuits, and major championships-created career pathways and commercial ecosystems. These systems required codified governance: constitutions, membership criteria, disciplinary mechanisms and transparent financial reporting to sustain legitimacy and investment.

Qualification and ranking frameworks organized meritocratic access while preserving historical traditions. Tournament entry, exemption categories and world-ranking algorithms now mediate mobility across levels, balancing competitive integrity with market imperatives and spectator engagement.

- Transparency: public reporting of governance decisions, budgets and conflicts of interest.

- accountability: independent oversight bodies and clear disciplinary procedures.

- Participation: stakeholder portrayal for players, clubs and commercial partners.

- Integrity: anti-corruption, anti-doping and equipment compliance regimes.

| Governing Body | Founded | Core Function |

|---|---|---|

| The R&A | 1754 | Rules & championships |

| USGA | 1894 | Rules & handicaps |

| PGA | 1916 | Professional development |

Robust governance demands continual reform: independent audits, open-data portals for decision records, and ethics committees with real sanctioning authority. Embedding these mechanisms reduces agency costs and reinforces public trust in the sport’s institutions.

As golf globalizes, institutions must reconcile commercial growth with equitable access, sustainability and technological change. The enduring imperative is clear: governance that is transparent,participatory and rule-bound will best preserve the game’s competitive fairness and social legitimacy.

Social Dynamics, Class and Identity: Gender, Race, and Access in golf History with Policy Recommendations to Promote Inclusion

Golf’s institutional architecture has long reflected and reinforced social stratification: private clubs, entrance fees, and residential course developments operated as mechanisms of economic gatekeeping, producing spatial and cultural exclusivity. Scholars identify these structures as formative in shaping who could claim golf as a domain of leisure and social capital; the sport’s norms and rituals – from clubhouse etiquette to membership sponsorship – became proxies for broader class identity. Policy responses must therefore interrogate not only access to greens but the economic infrastructures that maintain exclusionary membership models.

Gendered practices in golf created parallel but unequal spheres of participation. For much of the twentieth century, women were relegated to restricted tee times, separate competitions, and marginal club roles, while prevailing discourses about physiology and propriety were invoked to delimit competitive opportunity. Progress has been achieved through institutional reforms and the professionalization of women’s golf, yet persistent disparities in prize purses, media visibility, and administrative representation reveal structural inertia. Bold corrective measures require targeted investments to normalize women’s leadership in clubs, coaching, and tournament governance.

Racial exclusion shaped course siting, hiring practices, and tournament entry long before contemporary diversity frameworks emerged. Segregationist policies, discriminatory covenants, and informal ostracism impeded pathways for Black, Indigenous, and other historically excluded players and workers, eroding potential avenues for intergenerational mobility. Counter-histories – exemplified by pioneers such as Charlie Sifford and Lee Elder – underscore both the resilience of marginalized golfers and the limits of symbolic breakthroughs in the absence of systemic change. Meaningful inclusion therefore demands reparative attention to employment, land use, and representation.

Effective, evidence-based reforms should be specific, enforceable, and measurable; recommended actions include:

- Financial access: subsidized junior programs, reduced public-course fees, and community scholarship funds;

- Representation: quotas or incentives for diverse board membership and coaching staff;

- transparency: mandatory reporting on membership demographics and hiring practices.

| Barrier | Policy Response | Short Metric |

|---|---|---|

| Cost | Subsidized lessons & green fees | % youth enrolled |

| Representation | Diverse board targets | % leadership diversity |

| Historic exclusion | Land & hiring reparations | New hires & community grants |

Implementation must be accompanied by rigorous monitoring, independent audits, and community governance to prevent performative compliance. Establishing baseline data, publishing annual inclusion metrics, and tying public funding or tax incentives to demonstrable progress will create accountability loops. Cross-sector partnerships – municipal agencies, philanthropic foundations, and historically marginalized community organizations – are essential to scale prosperous pilots and institutionalize equitable practices.Ultimately, durable change requires integrating access, representation, and reparative investment into the core operating logic of golf institutions rather than treating inclusion as an optional add-on.

Commercialization, Media, and Global Diffusion: Economic Forces shaping Golf and Strategic Recommendations for Equitable Growth

The commercialization and media amplification of golf over recent decades have reconfigured the sport from a predominantly local pastime into a globally traded cultural product. Escalating broadcast rights, sponsorship portfolios, and digital content monetization have concentrated revenue streams at the elite level while reshaping competitive calendars and course design priorities. These market dynamics interact with macroeconomic currents-technological change, geoeconomic fragmentation, and shifting consumer preferences-highlighted in the World Economic forum’s analyses as central forces that reallocate capital and attention across sectors. In result,governance choices in leagues,federations,and national associations determine whether commercialization yields broad participation benefits or entrenches exclusivity.

Labor and skills are increasingly salient vectors linking economic change to the sport’s diffusion. The World Economic Forum’s Future of Jobs Report 2025 underscores rapid skill obsolescence and the rise of green and digital competencies; analogous trends are visible in golf where turf science, agronomy, data analytics, and sustainable facility management are supplanting traditional labor roles. This creates both opportunity and risk: new, higher-skilled jobs can support equitable regional development if accompanied by training pipelines, yet an absence of reskilling initiatives can exacerbate local unemployment and reduce grassroots capacity. Policymakers and industry actors must thus prioritize workforce transitions as an integral component of strategy.

Equity and environmental externalities demand targeted interventions that align commercial incentives with public value. Strategic recommendations include:

- Revenue-sharing frameworks-allocate a portion of broadcast and sponsorship income to community access funds and junior development programs.

- Investment in reskilling-public-private partnerships to deliver agronomy, green-tech, and digital media curricula tied to local employment pathways.

- Sustainable land-use policies-incentivize regenerative course practices and water-efficient designs through tax credits and certification schemes.

- Digital access initiatives-use streaming platforms and virtual coaching to lower entry barriers and expand participation in underserved regions.

Below is a concise mapping of principal economic drivers, observable impacts, and concise strategic responses to inform policy and industry planning.

| Economic Driver | Primary Impact | Strategic Response |

|---|---|---|

| Media monetization | Concentration of revenues | Revenue-sharing & grassroots funds |

| Green transition | New sustainability costs/opportunities | Incentives for regenerative courses |

| Technological change | Demand for digital skills | Training partnerships & certification |

Operationalizing equitable growth requires measurable frameworks: track participation rates by socioeconomic strata, incorporate environmental performance metrics into tournament licensing, and align media contracts with community obligations. Consistent with the World Economic Forum’s emphasis on anticipating workforce transitions amid uncertainty, stakeholders should adopt scenario planning and invest in modular training that bridges present roles to emergent occupations. Through coordinated governance-combining regulatory levers, commercial incentives, and targeted education-the sport can harness commercialization and media reach to foster inclusive, resilient, and sustainable global diffusion.

Heritage Conservation and Future Directions: Integrating Historical Knowledge into Sustainable Policy,Education,and Community Engagement

conserving the material and intangible dimensions of golf-historic fairways,early clubhouse architecture,archival rulebooks,and community practices-requires positioning these assets within broader frameworks of cultural landscape management and environmental stewardship. Recognizing golf heritage as both a repository of social history and a living ecological system enables policymakers to reconcile **historic integrity** with contemporary sustainability imperatives. Integrative strategies should treat historic courses not as static monuments but as dynamic sites where conservation objectives, climate adaptation, and recreational use are negotiated through evidence-based planning and cross-sector governance.

Embedding historical knowledge into formal and informal education strengthens collective capacity to steward golf’s past while guiding future decision-making. Curricula at secondary and tertiary levels,continuing professional development for club managers,and public interpretation programs can all transmit technical and ethical dimensions of heritage care. Key initiatives include:

- Curriculum integration – modules on landscape history, materials conservation, and the social history of sport;

- Apprenticeships and training – hands-on skills in turf heritage, restoration carpentry, and archival handling;

- Digital archives – accessible collections of photographs, maps, and oral histories to support research and community memory.

Community engagement must foreground participatory stewardship,recognizing local clubs,volunteers,and user communities as primary custodians. Collaborative research and co-curation enhance legitimacy and ensure policies reflect lived experience. The following concise stakeholder-role matrix illustrates practical alignments that facilitate sustainable outcomes:

| Stakeholder | Primary Role |

|---|---|

| Local clubs & members | Custodianship, oral histories |

| Municipal planners | Zoning, resilience planning |

| Museums & universities | Research, archival stewardship |

Operationalizing engagement also involves volunteer-driven maintenance programs, community-led interpretation projects, and ethically conducted oral-history initiatives that document diverse narratives of play, labor, and access.

To translate heritage values into durable policy,regulators and stewards should deploy a mix of regulatory and incentive-based instruments that align conservation with ecological outcomes.Policy mechanisms that have proven effective elsewhere-and that merit adaptation for golf landscapes-include:

- Heritage designation with adaptive management – legal protection that allows for incremental, science-guided interventions;

- Incentives for biodiversity-friendly practices – grants or tax relief for native-plant buffers and reduced chemical inputs;

- Conditional development controls – permitting frameworks that require heritage impact assessments and community consultation.

These tools must be designed with clear performance metrics and sunset provisions to prevent ossification of practices that may become maladaptive under changing climatic or social conditions.

Looking forward, interdisciplinary research and digital innovation will be central to sustaining golf heritage within equitable and resilient landscapes. Priorities include high-resolution GIS mapping of historic features, longitudinal ecological monitoring, and the development of a standardized **heritage integrity index** to guide conservation triage. Cross-sector governance models-bringing together planners, conservation scientists, historians, and community representatives-can turn archival knowledge into actionable strategies for adaptive reuse and sustainable tourism that support local economies without compromising heritage quality.Institutionalizing continuous learning and monitoring will ensure that historical knowledge is not only preserved but actively informs responsive policy and community practice.

Q&A

Note on search results: the web links provided in the prompt led to contemporary golf-forum pages and equipment threads that are not relevant to the historical, archival, and academic literature on golf’s evolution. The Q&A below therefore synthesizes established historical knowledge and scholarly perspectives rather than relying on those forum pages.

Q&A: “Golf’s Historical Evolution: Rules, Courses, Society”

1. What are the earliest origins of golf and the principal early documentary sources?

– Answer: Golf’s antecedents lie in a variety of stick-and-ball pastimes practiced in northwestern Europe; the game as we recognize it developed in Scotland in the late medieval and early modern periods. The earliest secure documentary sources include local references to “gowf” in Scottish records and, crucially, the 1744 “Articles and Laws in Playing at Golf” produced by the Company of Gentlemen Golfers of Leith (later the Royal and Ancient Golf Club of st Andrews). Other vital primary sources are club minute books,early scorecards,course maps,18th-19th century club rules,contemporary travelogues,and nineteenth-century newspaper accounts. for research, archival holdings at the R&A (St Andrews) and the USGA Museum & Library are indispensable.

2. How and when were golf’s rules standardized?

– Answer: Initially, rules were local – bespoke to particular clubs and courses. Formalization began with eighteenth-century club codes (notably the 1744 Leith rules). Over the nineteenth century, as the game spread beyond Scotland, national bodies formed: the Royal and Ancient Golf Club of St Andrews emerged as the principal authority in Britain, and the United States Golf Association (USGA) was founded in 1894 to coordinate rules and championships in the U.S. In the twentieth century, the R&A and USGA progressively harmonized their rulebooks and, by the mid-twentieth century, collaborated to issue a single international code with periodic joint updates. The rise of international competition and the globalization of play drove continued clarification and codification (e.g., definitions of hazards, relief, equipment conformity).

3. Why,and when,did the 18‑hole standard emerge?

– Answer: The 18‑hole round is a convention rather than a natural necessity. The Old Course at St Andrews originally featured a different number of holes; in 1764 several short holes were combined, producing an 18‑hole circuit that became customary for play at St Andrews. Because St Andrews was highly influential, that layout exerted normative pressure; by the nineteenth century other clubs had adopted 18 holes and it became the standard for competitions and course design. The shift reflects institutional influence, convenience for tournaments, and the establishment of par and scoring standards that assumed an 18‑hole frame.

4. How did course design evolve from “links” to the modern variety of courses?

– Answer: Early golf was played on coastal “links” – sandy, windswept terrain on which natural contours and hazards defined play.Course design in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries blended this naturalism with intentional routing and feature-making: figures such as Old Tom Morris, James Braid, and Willie Park Sr. shaped early design practice.The late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries saw the “golden Age” of course architecture (Donald Ross, Alister MacKenzie, Harry colt), where strategic design, bunkering, and variety of shot values were emphasized. In the twentieth century technological changes (earth-moving equipment, irrigation, mowing machinery) enabled internal, parkland, and desert courses in non‑coastal settings, giving rise to a global typology. Contemporary design stresses strategy, sustainability, and playability for diverse players.

5. Who are the historically notable golf architects, and what were their design principles?

– Answer: Significant architects include Old Tom Morris (early routing and green complexes), Willie Park Sr. (competitive routing), James Braid, Harry Colt, Alister MacKenzie (strategic design and the “natural” aesthetic), Donald Ross (greens with subtleties and strategic emphasis), and later figures such as Pete Dye and Robert Trent Jones Jr. Their shared principles varied across eras: early designers worked with natural features and strategic placement; Golden Age architects emphasized shot values and variety; mid‑ and late‑twentieth‑century designers integrated engineering and large-scale landscaping; contemporary designers additionally prioritize environmental stewardship and accessibility.

6. How has club and ball technology shaped the game?

– Answer: Technology has repeatedly transformed play. Pre‑nineteenth‑century balls (featheries) were hand‑stitched leather seeded with feathers; the introduction of the guttie (gutta‑percha) mid‑nineteenth century and, later, the rubber‑cored Haskell ball around the turn of the twentieth century substantially increased consistency and distance. Shaft technology moved from ash and hickory to steel and then to composite/graphite materials, changing feel and power transfer. Clubhead materials evolved from wood (“woods”) and forged irons to stainless steel, titanium, and multi‑material constructions with cavity backs and perimeter weighting. Each major leap affected playing strategy,course length,and governing bodies’ regulatory attention; the R&A and USGA have continually adjusted equipment conformity rules in response.

7. How have governing bodies regulated equipment and why?

– Answer: Governing bodies regulate equipment to preserve the integrity of shot‑making, fairness across skill levels, and the strategic character of courses. As equipment became more performance-enhancing, concerns arose about “distance creep” and the obsolescence of course architecture. Regulations have addressed ball construction, club face properties, grooves, length, and materials; conformity tests and approval processes are used. Joint R&A/USGA rulemaking seeks to balance technological innovation with historical continuity and safety, while allowing manufacturers to refine designs within limits.

8. What role did amateurism and professionalism play in golf’s social history?

– Answer: Golf’s social history has been marked by a long tension between amateurism (linked to the landed gentry and middle‑class gentlemanly ideals) and the rise of professional players (often working‑class clubmakers, caddies, and instructors). In the nineteenth century major tournaments like The Open allowed professionals, but many elite clubs privileged amateurs socially. Over time, professional tours (PGA, formed in 1916 in the U.S.; professional tournament circuits thereafter) and the establishment of prize money transformed golf into a spectator and commercial sport, altering social hierarchies and opening new career paths for players.

9. How have gender, race, and class shaped access to the game?

– Answer: access has historically been constrained by class, gender, and race. Golf clubs were often exclusive, with membership rules privileging men of certain social status; women organized their own institutions (e.g., the Ladies’ Golf Union in the U.K., late nineteenth century), and the LPGA was established in 1950 to professionalize women’s golf. Racial exclusion was explicit in some national organizations and clubs; for example, in the U.S. the PGA of America maintained a “Caucasian‑only” clause until 1961. Over the late twentieth and early twenty‑first centuries,legal change,activism,and commercial incentives have broadened participation,but disparities in access and representation persist globally. Municipal courses, public facilities, and targeted development programs have been central to democratization efforts.

10. When did golf globalize, and what forces drove that process?

– Answer: Golf expanded beyond Scotland largely through British imperial networks in the nineteenth century and through transatlantic cultural exchange. By the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, organized golf spread to continental Europe, North America, Asia, Africa, and the Pacific. Drivers included colonial administrators, military officers, merchants, expatriate communities, and later global media and commerce. Professional tours, international competitions (Dewar Cup, Walker Cup, Ryder Cup), and broadcast television in the mid‑twentieth century accelerated globalization and commercial expansion.

11. How have media, commercialization, and television changed the sport?

– Answer: Television and mass media transformed golf into a spectator commodity from the mid‑twentieth century onward. Broadcasts raised the profile of star players, amplified sponsorship and advertising revenues, and increased the financial stakes of professional tournaments. Commercialization altered tournament formats, course maintenance standards (to favor television aesthetics and shot‑making drama), and player incentives. It also encouraged the growth of ancillary industries (equipment manufacturing,apparel,tourism).

12. What environmental and land‑use critiques have been leveled at golf, and how has the industry responded?

– Answer: Critics point to high water use, pesticide and fertilizer dependence, habitat conversion, and the privileging of elite land use. In response, the industry has developed sustainability initiatives: native vegetation use, efficient irrigation and reuse, integrated pest management, wildlife habitat programs, green certification schemes, and design approaches that reduce earth‑moving and preserve ecosystems. Environmental management has become a central part of modern course planning and governance, with a rising academic literature on best practice and impact assessment.

13. What are the major contemporary debates shaping golf’s future?

– Answer: Key debates include equipment regulation versus innovation (particularly distance control), accessibility and diversity in participation, the environmental footprint and climate resilience of courses, the economic model of professional tours, and the preservation versus modernization of historic courses. There is also discussion about how to adapt formats and facilities to attract younger and more diverse players while maintaining traditions that many value.

14. What methodological approaches are useful for studying golf historically?

– Answer: Multi‑method approaches are fruitful: archival research (club minutes, rulebooks, early periodicals), oral history with players and designers, material culture studies (clubs and balls), landscape and environmental history (course archaeology and land use change), social history (class, gender, race), and economic and media history (commercialization and broadcasting). comparative and transnational studies help trace diffusion and local adaptation.Interdisciplinary engagement with sport studies, design history, and environmental science is especially valuable.

15. Where should scholars and students look next for primary and secondary sources?

– Answer: Key repositories include the R&A Archives (St Andrews), the USGA Museum & Library (Far Hills/NJ and archives), national and municipal archives (club records, planning documents), and period newspapers. Scholarly journals such as Sport in History, the International Journal of the History of Sport, and environmental history journals publish relevant work. Monographs and edited volumes on the social history of sport, the history of technology, and landscape architecture provide comparative frameworks. interviews with course architects, grounds professionals, and governing‑body archivists can yield original material.

Concluding note

This Q&A frames golf’s evolution as a dynamic interplay among rules and governance, technological change, design and landscape, and shifting social meanings. For academically rigorous work, pair the broad narrative above with targeted archival research and engagement with the multidisciplinary literatures on sport history, material culture, and environmental studies.

to sum up

In tracing golf’s trajectory from its putative origins in fifteenth-century Scotland to its present-day global diffusion, this study has shown how rules, courses, and societal forces have co‑constituted the game’s identity. The formalization of rules has both reflected and regulated play, anchoring a transhistorical continuity even as successive revisions respond to technological innovation and shifting ethical expectations. Course design has operated as a material vocabulary through which cultural values, landscape aesthetics, and technological capacities are inscribed; fairways and greens therefore function as texts as much as terrains. Social transformations-class formation, gendered access, commercialisation, and globalization-have repeatedly reconfigured who plays, how the game is governed, and what meanings it carries in diverse contexts.

The interplay among regulation, built environment, and social context highlights key tensions that continue to shape golf’s evolution: the preservation of tradition versus the imperatives of inclusion and modernization; the sport’s commercial and media logics versus commitments to heritage and local stewardship; and recreational practice versus environmental sustainability. Understanding these tensions demands approaches that are sensitive to historical contingency while attentive to present‑day policy and ethical considerations, particularly around equity, environmental impact, and the governance of public and private spaces.

Future research would benefit from deep archival work on early rule‑making and club histories, comparative analysis of regional design practices, ethnographies of participation across diverse communities, and interdisciplinary studies linking material culture, landscape ecology, and technological change. Empirical inquiry into contemporary governance structures, sustainability initiatives, and the socioeconomics of access will be especially critically important for informing policy and practice.Methodologically, integrating GIS and digital reconstruction with qualitative archival and oral histories can illuminate both the embodied and environmental dimensions of the game’s past and present.

In sum, the history of golf is not merely a chronicle of equipment and etiquette but a prism through which broader social, cultural, and environmental histories can be read. Its enduring traditions and ongoing transformations make golf a fruitful subject for continued scholarly attention-one that can enrich not only sports history but also debates about landscape, leisure, and social change.

Golf’s Historical Evolution: Rules, Courses, society

origins and early forms of golf

Golf’s roots reach back centuries and cross cultures. While games involving balls and sticks appeared in medieval Europe and asia (examples include Scottish stroke-and-putt games and earlier Chinese games like chuiwan), the modern sport we call golf developed most recognizably in Scotland. early references show that golf was being played on coastal “links” land near St Andrews and across eastern Scotland by the late middle Ages. As of its popularity and the perceived distraction from military training, Scottish authorities sometimes banned the game – such as, the 1457 statute encouraging archery practice over golf.

From recreation to codified sport

Key milestones in early codification include the 1744 rules published by the Gentlemen Golfers of Leith (often cited as the first written rules) and the founding of the Royal and Ancient Golf Club of St Andrews in 1754. These local efforts established many conventions that would later evolve into formalized rules of golf, etiquette, and competition formats.

How the 18-hole standard emerged

One of golf’s most famous innovations – the 18-hole round – emerged from local practice rather than central decree. The Old Course at St Andrews originally had a different number of holes; in 1764 the course reduced and consolidated its routing to 18 holes. As St Andrews was already a focal point for early organized golf, other clubs began to emulate the 18-hole layout and the format became standard worldwide. Today, “18-hole golf” is a global baseline for stroke play and many forms of competition.

Governing bodies and the standardization of rules

As golf spread beyond Scotland, the need for consistent rules and handicapping grew. Importent institutions and rule milestones include:

- Royal and Ancient Golf Club (R&A) – Founded at St Andrews in 1754, later became an influential rule-making body for much of the world.

- United States Golf Association (USGA) – Formed in 1894 to govern golf in the United States and Mexico, focusing on rules, championships, and equipment standards.

- joint rules growth – Over the 20th century the R&A and USGA coordinated increasingly; they now jointly publish the Rules of golf and have modernized the rules together in major updates (notably the 2019 Rules of Golf revision).

- World handicap System (WHS) – Launched in 2020 by golf’s governing bodies to unify handicap calculation internationally, making competitive golf more equitable across courses and countries.

Landscapes of play: evolution of golf course design

Golf course design evolved from natural seaside links to a rich vocabulary of styles, driven by culture, climate, and design ideology:

- Links courses – Customary coastal courses in Scotland and Ireland, featuring firm turf, dunes, and wind as a strategic element.

- Parkland courses – Inland venues with tree-lined fairways,softer ground conditions,and manicured landscapes.

- Resort and desert courses – Adaptations that use irrigation and modern construction techniques to overcome local limitations.

- Modern championship courses – Frequently enough use strategic bunkering, multiple tees, and advanced agronomy to test elite players.

Course architecture and notable influences

Course architects such as Old Tom Morris, Alister MacKenzie, Donald Ross, Robert Trent Jones, and more recently Pete Dye and Tom Doak, reshaped how designers thought about strategic risk-and-reward, green complexes, and routing. Advances in agronomy and drainage also allowed architects to build courses in previously unsuitable places, widening golf’s footprint globally.

Equipment, technology, and their effect on rules and courses

equipment innovations have repeatedly altered play and prompted rule adaptations.

- Transition from featherie to gutta-percha balls (19th century) to rubber-core (Haskell) balls late 1800s – led to greater distance and consistency.

- From wooden shafts to steel, and later graphite – changing feel, durability, and performance.

- The introduction of metal woods (drivers), multi-layer balls, and modern club engineering – increased driving distance and altered course setup considerations.

These changes prompted governing bodies to regulate club and ball specifications to preserve the integrity of competition. course architects and tournament committees responded by lengthening courses, redesigning hazards, and rethinking green complexes.

Rules of golf: major shifts and clarifications

The Rules of Golf are both historical and evolving. Major changes in recent decades include:

- Modernization of rule language and structure in the 2019 Rules of Golf, intended to simplify and clarify play for amateurs and professionals alike.

- Ban on anchoring the club (effective in 2016) – the R&A and USGA outlawed anchoring a putter or long putter to the body for strokes during competition.

- Clarifications on relief (ground under repair, abnormal course conditions), preferred lies, and pace-of-play guidance – designed to make decision-making quicker and fairer on course.

Etiquette, tradition, and the social code of golf

Golf’s culture combines formal rules with unwritten etiquette: honesty in scoring, respect for fellow players, care for the course (repairing divots, raking bunkers), and maintaining reasonable pace of play. Clubs developed customs – dress codes, tee reservation norms, and membership rituals – that shaped golf as both sport and social institution.

From exclusive clubs to broader participation

Historically, many golf clubs were socially exclusive, with membership policies reflecting the norms of their time. Over the 20th and 21st centuries, public golf courses, municipal programs, youth initiatives, and diversity efforts expanded access. Women’s golf organizations, junior programs, and community outreach have all contributed to diversifying the sport. Still, discussions about equity and accessibility remain active topics within the golf community.

Handicaps, scoring formats, and competitive structures

Handicapping systems let players of different abilities compete fairly. The World Handicap System standardizes calculation and course rating methodology, allowing golfers to translate performance across different courses. Key scoring formats include:

- Stroke play – total strokes determine the winner (used in most major tournaments).

- Match play – head-to-head hole-by-hole competition.

- Stableford and par competitions – option scoring to encourage aggressive play or speed up play.

Case study: St Andrews and The Open Championship

St Andrews – often called the “Home of Golf” – illustrates many threads of golf history: the 18-hole standard, links tradition, and the establishment of early clubs.The Open Championship (the British Open), inaugurated in 1860, is the oldest of the four major professional championships and has been instrumental in shaping professional competition, course setup standards, and spectator culture.

Practical tips for clubs, historians, and golfers

- For club managers: Embrace sustainable agronomy, preserve historic routing where possible, and update local rules to align with the 2019 Rules and WHS guidelines.

- For tournament organizers: apply course rating measures and tee options to create fair, competitive conditions across ability levels.

- For golfers and historians: Use primary sources (club minutes, early rules pamphlets), course maps, and archived championship records to trace changes in equipment, rules, and play.

Timeline of pivotal milestones

| Year | Milestone | Impact |

|---|---|---|

| 1457 | Scottish parliamentary bans | Shows early popularity and social conflict |

| 1744 | First written rules (Leith) | Start of structured play and competition |

| 1754 | R&A founded (St Andrews) | Long-term influence on rules and tradition |

| 1764 | Old Course adopts 18 holes | 18-hole round becomes standard |

| 1894 | USGA established | Governing body for the U.S. and Mexico |

| 1898 | Haskell rubber-core ball | Increased distance; equipment revolution |

| 2016 | Anchoring ban | Equipment and technique regulation |

| 2019 | Rules modernization | Simplified language and clearer relief options |

| 2020 | World Handicap System | Unified handicapping globally |

First-hand outlook: what golfers feel when tradition meets modernity

Walk a traditional links course and you’ll sense continuity: the wind, the firm fairways, the patchwork turf tell a story of place and history. At the same time, players bring modern equipment, GPS rangefinders, and global handicaps. That blend – respect for heritage alongside technical progress – is central to golf’s enduring appeal. players often report that learning the history of a course enhances strategic thinking: understanding why a bunker sits where it does or why a green slopes a certain way gives insight into risk-taking and shot selection.

SEO-focused keywords used naturally in this article

- golf history

- rules of golf

- 18-hole golf

- golf course design

- R&A and USGA

- golf etiquette

- golf equipment evolution

- World Handicap System

- links golf

- golf traditions

For researchers, players, and golf clubs alike, understanding the historical evolution of golf – from rules and course architecture to social impact and equipment – offers richer play and better stewardship of the game. Use the timeline and practical tips above to explore further, whether you’re restoring a course, revising club rules, or simply curious about how modern golf became what it is today.