Introduction

The follow-through phase of the golf swing is more than an aesthetic finish: it is an integral component of the motor task that governs ball direction, shot consistency, and risk of musculoskeletal injury. Whereas much research and coaching attention emphasizes backswing and impact mechanics, the follow-through encapsulates the terminal regulation of segmental motion and energy dissipation that determines the fidelity of momentum transfer from player to club and ultimately to the ball.Characterizing the kinematics and neuromuscular control of this phase is therefore essential for a complete biomechanical account of skilled golf performance and for evidence-based recommendations to improve accuracy and reduce injury risk.

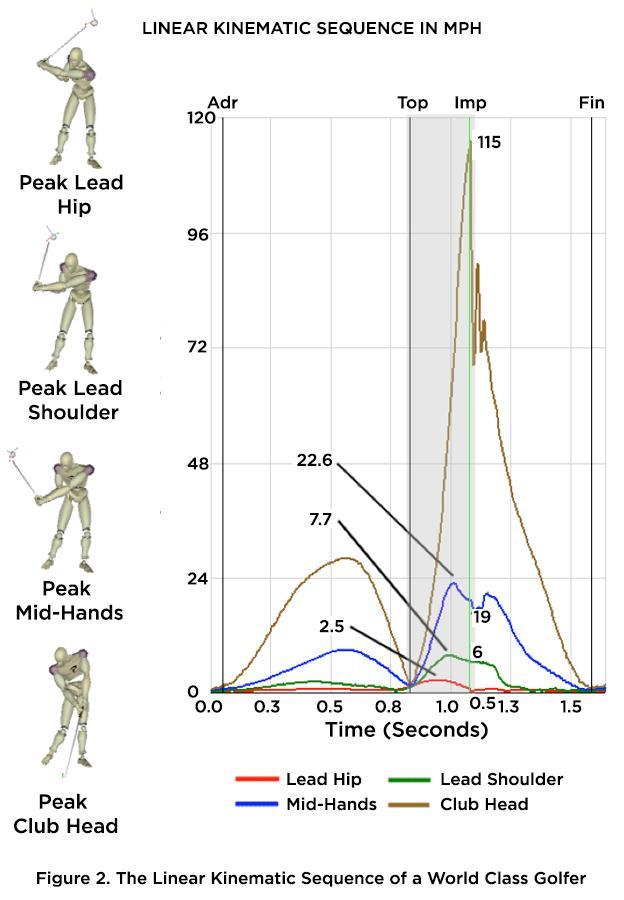

From a kinematic outlook, the follow-through can be described by the spatiotemporal patterns of segment orientations, joint angular velocities and accelerations, and the temporal sequencing that governs proximal-to-distal energy transfer. Kinematic analysis isolates the motion variables-timing of peak angular velocities,intersegmental coordination,and path variability-that underlie effective momentum propagation and controlled deceleration without necessarily invoking the forces that produce them. Vital kinematic signatures include the timing relationships among pelvis, thorax, shoulder, elbow and wrist rotations, peak rotational speeds, and the trajectories these segments follow after ball release.

complementing kinematics,the neuromuscular basis of follow-through addresses how the central nervous system organizes muscle activation to achieve the required motion patterns. Key neuromuscular elements include anticipatory feedforward activation that sequences muscles for efficient energy transfer, phasic eccentric contractions and co-contraction strategies that provide controlled braking of distal segments, and sensorimotor feedback processes that refine terminal adjustments based on proprioceptive and vestibular inputs. Understanding these activation patterns-often quantified with electromyography and related measures-explains how athletes achieve both powerful and stable terminations of the swing and how mal-coordination can predispose to overuse injury.

Empirical inquiry of follow-through therefore typically integrates three methodological strands: high-resolution motion capture to quantify kinematic variables; electromyography (EMG) and neuromuscular assays to characterize temporal patterns and intensity of muscle activity; and kinetic measurements or inverse dynamics to infer joint torques and energy flow. Computational modeling and statistical analysis of intertrial variability further enable inference about control strategies, robustness, and the trade-offs between performance (accuracy and consistency) and tissue loading. Such multimodal approaches permit hypotheses about proximal-to-distal sequencing,momentum transfer efficiency,and active deceleration mechanisms to be tested and related to coaching interventions.

This article synthesizes current biomechanical and motor-control perspectives on the golf follow-through, presents an integrated framework linking kinematics to neuromuscular control, and outlines empirical methods for their study. By elucidating how coordinated joint sequencing and neuromuscular strategies produce effective momentum transfer and safe deceleration, we aim to inform evidence-based coaching, targeted conditioning protocols, and injury-prevention measures that enhance both performance and longevity in golfers.

Kinematic Chain and Joint Sequencing During the Follow Through

The follow-through is best understood as a coordinated kinematic chain where proximal segments generate and sequentially transfer angular momentum to distal segments. In biomechanical terms this is a proximal-to-distal sequencing pattern: pelvis rotation and hip extension initiate torso angular acceleration,the thorax and shoulder complex amplify and redirect that rotation,and the forearm/wrist complex refines clubhead velocity and orientation. Conceptually this resembles a kinematic coupling in multi-body models, where a small set of control variables (or control points) enforces coordinated motion across linked segments to preserve desired timing and orientation relationships.

Sequencing of joints follows a reproducible temporal order that maximizes velocity while maintaining control. Typical elements of the sequence include:

- Pelvis – axial rotation and weight transfer to create base angular momentum;

- Thorax – rapid rotation and separation from the pelvis to amplify trunk angular velocity;

- Shoulder complex – controlled adduction/rotation that channels energy to the arm;

- Elbow – timed extension that positions the distal segment for release;

- Forearm/wrist – pronation/supination and flexion/extension that finalize clubhead speed and face angle.

Each link contributes both magnitude and timing; small phase shifts (tens of milliseconds) alter launch conditions substantially.

From a neuromuscular standpoint, sequencing is implemented through temporally precise muscle activation patterns-phasic bursts in agonist muscles and anticipatory co-contraction in stabilizers. It is indeed critically important to distinguish kinematic description (motion patterns and sequencing) from kinetics or dynamics (forces and torques that produce those motions). While this section emphasizes kinematics, practitioners should be mindful that force-generation capacity and intersegmental torque transfer ultimately constrain feasible kinematic strategies and influence injury risk.

Effective follow-through control requires active deceleration of specific segments to preserve accuracy and protect tissues. Eccentric muscle actions in the shoulder rotators, elbow flexors and wrist extensors act as controlled brakes after ball release; anticipatory modulation of these brakes reduces variability in clubface orientation. Practical control strategies include:

- Graded eccentric control of shoulder external rotators to slow internal rotation;

- Progressive distal stiffening through timed co-contraction of forearm flexors/extensors to stabilize the wrist;

- Sequencing drills that exaggerate proximal initiation and delay distal release to ingrain timing without overloading tissues.

These strategies balance momentum transfer with purposeful dissipation of energy to optimize accuracy and reduce cumulative loading.

| Segment | Relative Peak Angular velocity | Typical Timing (ms after impact) |

|---|---|---|

| Pelvis | 0.6 | -30 |

| Thorax | 1.0 | 0 |

| Forearm/Wrist | 0.8 | +20 |

Quantitative assessment using high-speed motion capture or inertial sensors can verify whether an individual’s segmental timing and peak velocities align with these functional targets; deviations suggest either neuromuscular timing deficits or compensatory kinetic strategies that warrant targeted intervention.

Momentum Transfer and Energy Dissipation From Impact to Finish

At the instant following ball contact, the system transitions from energy delivery to controlled dissipation. Residual angular and linear momentum, previously funneled into the ball, must be redistributed across the wrist, elbow, shoulder, trunk, hips, and lower limbs. From a mechanical perspective this phase is governed by conservation of angular momentum of the body-club system, segmental moment of inertia, and intersegmental forces that produce internal work. The net effect is a cascade in which kinetic energy is absorbed by tissues, converted to heat, and redirected into stabilizing impulses that determine post-impact trajectory control and repeatability.

Neuromuscular control during this interval emphasizes timed eccentric actions and coordinated co-contraction to dissipate energy without compromising rotation. Key strategies include eccentric braking of the lead (target-side) shoulder and elbow extensors, anticipatory activation of trunk rotators to arrest excessive axial rotation, and modulation of wrist flexor-extensor activity to prevent unwanted clubface rotation. these actions are not reflexive onyl; they reflect feedforward motor programs fine-tuned by practice, with afferent feedback adjusting late-phase muscle activity to maintain accuracy under variable impact conditions.Eccentric capacity and timing precision therefore are as important as concentric power for a controlled finish.

The kinetic interplay across joints can be summarized succinctly:

- Proximal-distal dissipation: Pelvis and trunk absorb and re-route rotational energy.

- Distal buffering: Shoulder/elbow complex attenuates residual club energy through controlled deceleration.

- Lower-limb grounding: Ground reaction forces (GRF) provide the external impulse necessary to stabilize the system.

To illustrate typical mechanical roles in the finish, the following compact table maps phases to principal contributors:

| Phase | Primary Mechanism | Key Muscles |

|---|---|---|

| Immediate post-impact | residual angular transfer | Forearm/wrist extensors |

| Mid follow-through | Eccentric trunk deceleration | Obliques, erector spinae |

| Finish stabilization | Ground reaction absorption | Gluteus medius/maximus, quads |

Ground reaction forces modulate how momentum is redirected into the earth and thus are central to both consistency and injury risk reduction. controlled weight transfer toward the lead side increases vertical and posterior-directed GRFs that facilitate safe dissipation of rotational energy; conversely, abrupt or asymmetric GRFs can concentrate load in the lumbar spine or lead shoulder. Practical cues that reflect these principles include:

- “Finish over your front foot” – promotes GRF-mediated braking.

- “Soft elbows” – encourages eccentric absorption rather than rigid joint locking.

- “Rotate through the chest” – engages trunk musculature to distribute torque.

Applying these biomechanical insights yields concrete training recommendations. Strength and conditioning should prioritize eccentric strength of the upper limb and trunk, rotational stability, and unilateral lower-limb force absorption drills to improve GRF control. Motor-control work – including variable-speed impact drills and constrained-feedback practice – refines the timing of deceleration synergies that underpin shot-to-shot repeatability. Clinically, assessing eccentric capacity and intersegmental coordination after fatigue or injury provides predictive information about a player’s ability to dissipate impact energy safely, linking mechanical efficiency directly to performance and injury prevention.

neuromuscular Activation Patterns Underlying controlled Deceleration

Precise temporal coordination of muscle activity after ball release is characterized by a rapid shift from high-velocity propulsion to controlled energy dissipation. Proximal segments (pelvis and trunk) initiate the deceleration cascade through graded eccentric activity of the lumbar extensors and obliques, while distal segments (shoulder, elbow, wrist) employ coordinated eccentric braking to attenuate residual clubhead momentum. Key stabilizers-**rotator cuff**, **scapular retractors**, and **forearm flexors/extensors**-exhibit early, sustained activation to preserve joint centration and minimize translational loading that would or else degrade accuracy.

Neuromotor control integrates feedforward anticipatory commands with short-latency reflex modulation to manage impact-transmitted forces. Anticipatory activation primes muscle stiffness and joint impedance prior to contact, whereas feedback-driven adjustments refine deceleration magnitude and timing in response to sensory input. Functional co-contraction across antagonistic pairs increases joint stability during high-rate eccentric work, trading some energetic efficiency for enhanced positional control-an adaptive strategy essential for repeatable shot dispersion and injury mitigation.

The following concise summary synthesizes typical electromyographic observations and functional roles of primary muscle groups involved in post-impact braking:

| Muscle Group | Dominant Activation mode | Functional Role |

|---|---|---|

| Lumbar extensors & obliques | Eccentric/Isometric | trunk deceleration and torso stabilization |

| Rotator cuff (supraspinatus, infraspinatus) | Eccentric | Control humeral head position and absorb rotational torque |

| Wrist/finger flexors & extensors | Eccentric | Dissipate distal energy; fine-tune club face orientation |

Integrity of peripheral nerves, neuromuscular junctions, and muscle tissue is essential to executing these activation patterns; disruptions-whether from acute overload, chronic tendinopathy, or neuromuscular disease-can impair timing and amplitude of braking responses, increasing variability and injury risk.Rehabilitation and conditioning should thus emphasize **eccentric strength**, proprioceptive acuity, and intersegmental coordination rather than isolated power development alone. Targeted neuromuscular retraining restores efficient braking strategies and supports long-term tissue resilience.

From a coaching and applied-science perspective, actionable emphases include:

- Tempo modulation drills to optimize anticipatory activation and reduce excessive distal velocity.

- Eccentric loading progressions for rotator cuff and forearm musculature to improve energy absorption capacity.

- Reactive stability exercises (perturbation and balance tasks) to enhance sensory-motor integration under dynamic load.

Quantitative assessment using synchronized EMG and kinematic capture can objectively track neuromuscular adaptations to training and identify atypical activation signatures that merit corrective intervention.

Temporal Coordination and Timing Strategies for consistent Ball Flight

temporal coordination in the golf swing is best conceptualized as a precisely timed cascade of segmental accelerations that translates stored and generated energy into clubhead velocity at impact. Effective follow-through depends on preserved **proximal-to-distal kinematic sequencing**-pelvic rotation initiating trunk rotation, trunk rotation driving shoulder and arm motion, and the arm/club complex producing the final impulse. Consistent ball flight emerges when the relative timing (order and overlap) of these events is reproducible across repetitions, minimizing unwanted coupling that produces lateral dispersion or spin variability.

Neuromuscular control underpins that sequencing through anticipatory activation and finely tuned intermuscular coordination. Feedforward programs set muscle onset and amplitude to stabilize posture (anticipatory postural adjustments) and to time the transfer of momentum, while reflexive feedback refines late-phase corrections. Empirical EMG patterns typically show graded activation of prime movers and stabilizers (hip extensors, obliques, erector spinae, rotator cuff) timed to preserve segmental inertia and to permit efficient dissipation of energy in the follow-through. Reducing within-player variability of these activation patterns correlates with improved repeatability of launch conditions.

Training strategies to entrain timing should combine perceptual cues,constrained practice,and progressive complexity. Effective drill categories include:

- Rhythm and metronome drills: synchronize weight shift and pelvic rotation to internal timing cues to stabilize phase durations.

- Pause-and-release drills: impose brief holds at transition to highlight correct sequencing on resumption.

- Impact-proximity drills: focus on accelerating the distal chain while maintaining proximal stability (e.g., short-swing punch shots).

- Augmented-feedback drills: use delayed auditory or vibrotactile cues to shift reliance from immediate sensory feedback toward feedforward timing.

Quantifying temporal performance permits objective feedback and targets for intervention. Commonly useful metrics and sensing modalities include peak angular velocity order, time-to-peak for pelvis/thorax/club, and ground-reaction force (GRF) impulse timing. The table below provides concise sampling of relevant measures and practical interpretation.

| Metric | Sensor | Interpretation / Target Pattern |

|---|---|---|

| peak pelvis → peak thorax | IMU/3D motion | pelvis leads thorax (clear proximal-to-distal) |

| Time-to-peak club velocity | High-speed video / IMU | Consistent onset across reps → stable ball speed |

| GRF lateral shift timing | Force plate | Predictable weight transfer preceding impact |

Designing practice around motor learning principles enhances transfer of temporal skills to on-course performance. Emphasize **external focus cues** (e.g., ball flight target), introduce variability (contextual interference) to foster adaptable timing, and progress from blocked to random schedules to consolidate feedforward programs. Prioritize reproducible phase relationships over maximal speed during early learning; once temporal templates are stable,integrate power-focused work while monitoring that the kinematic sequencing remains intact.

Segmental Contributions to Accuracy and Shot Shape control

Precision of ball flight is not dictated by any single joint but by the coordinated timing and magnitude of impulses across segments.Contemporary kinematic analysis shows that **proximal-to-distal sequencing** during the follow-through governs both clubhead path and clubface orientation at and instantly after impact-factors that determine lateral dispersion and shot curvature. Small alterations in the temporal ordering of trunk deceleration, arm extension, and wrist rotation disproportionately affect the final clubface angle, making segmental coordination a primary determinant of accuracy.

The axial system-pelvis and thorax-functions as the primary torque generator and regulator. Controlled **trunk rotation and timely pelvic dissociation** create the torque necessary for high clubhead speed while also anchoring the rotational axis that the arms and club trace. Over-rotation or early trunk deceleration shifts the club path and induces face-open/face-closed tendencies; conversely, optimal transverse-plane kinematics produce consistent launch direction and predictable side spin characteristics.

Distal upper-limb mechanics translate proximal torque into final clubface behavior. The lead arm’s degree of extension defines the swing radius and influences the plane of motion, while forearm pronation/supination and wrist dynamics fine-tune face rotation at impact. Neuromuscular control-specifically **timed agonist-antagonist co-contraction** around the elbow and wrist-stabilizes the distal chain during the rapid deceleration of the follow-through, reducing unintended face rotation and thus minimizing shot dispersion.

Ground-reaction forces and lower-limb stabilization provide the reactive foundation for reliable segmental transfer. Effective weight transfer and controlled lateral braking produce the counterforce against which trunk and arm segments generate angular momentum; deficits here manifest as compensatory mid-upper-body movements and variable clubface presentations. Sensory feedback from the ankles and hips (proprioception) is therefore critical for maintaining the platform stability required for precise shot-shape control.

Translating these insights into practice requires targeted neuromuscular and technical interventions. Key training emphases include:

- Trunk timing drills to optimize rotation-to-deceleration sequence.

- Lead-arm extension control exercises to stabilize swing radius.

- Forearm/wrist activation patterns to manage pronation timing.

- Lower-body stabilization and reactive force training for consistent platforms.

| Segment | Primary Contribution | Representative Metric |

|---|---|---|

| Pelvis/Trunk | Torque generation & axis control | Rotation velocity (°/s) |

| Lead Arm | Arc radius & plane stability | Extension angle (°) |

| Wrist/Forearm | Final face orientation control | Pronation velocity (°/s) |

| Lower Limb | Platform stability & force delivery | Peak GRF (N) |

Clinical Risk Factors and Preventive Strategies for follow Through Related Injuries

Clinical presentations most commonly associated with follow‑through pathology reflect a convergence of modifiable and non‑modifiable elements. prominent **non‑modifiable factors** include age‑related tissue degeneration and previous surgical history, whereas **modifiable factors** encompass reduced thoracic rotation, glenohumeral internal rotation deficit, hip abductor weakness, and altered motor sequencing. Epidemiologically, athletes with high collision of peak clubhead velocity and limited capacity for eccentric deceleration demonstrate higher rates of rotator cuff tendinopathy, medial elbow overload, and lumbar facet irritation.

Mechanistically, maladaptive kinematic patterns convert kinetic energy into pathological tissue stress during the deceleration phase.Excessive late trunk rotation or delayed pelvic‑thoracic dissociation transfers disproportionate eccentric load to the shoulder and elbow extensors; conversely, deficient hip drive amplifies lumbar shear.At the neuromuscular level,delayed or attenuated activation of the **gluteus maximus**,**external obliques**,and **posterior rotator cuff** reduces capacity for graded braking and energy dispersion,precipitating microtrauma and symptomatic overload.

Evidence‑based preventive measures should be tiered across screening, corrective training, and on‑course modifications. Recommended interventions include:

- Pre‑season screening: validated movement tests for transverse plane rotation, single‑leg stability, and shoulder IR/ER strength ratios.

- Targeted loading programs: progressive eccentric and rotational strengthening emphasizing hip extensors and scapular stabilizers.

- Motor control drills: low‑velocity, high‑repetition deceleration tasks to retrain timing of muscle onset.

- Technique adjustments: swing sequencing modifications (earlier pelvic closure, moderated wrist release) and equipment tuning to reduce peak loads.

- Workload management: periodized practice with monitored swing counts and fatigue mitigation strategies.

Rehabilitation should integrate specific neuromuscular strategies that restore both force capacity and intersegmental timing. Programs combining eccentric rotator cuff training, hip abductor concentric/eccentric work, and sport‑specific deceleration progressions yield superior outcomes for return to unrestricted play. Clinicians should apply objective progression criteria (pain‑free functional tasks, normalized symmetry indices, and sensor‑derived kinematic markers) rather than time‑based rules alone. education on self‑monitoring and graduated reintroduction of high‑load swings reduces recurrence risk.

Implementation within clinical practice benefits from structured pathways and multidisciplinary collaboration. Use routine reassessment intervals and simple objective metrics to guide progression. The table below provides a concise clinical pairing of common risk factors with pragmatic preventive strategies for rapid clinic use.

| Risk Factor | Preventive Strategy |

|---|---|

| Thoracic hypomobility | Targeted mobility + rotary strength |

| Hip abductor weakness | Progressive hip‑dominant loading |

| Delayed deceleration timing | Neuromuscular timing drills & biofeedback |

Evidence Based Training Protocols to Enhance motor Control and Dynamic Stability in the Follow Through

Contemporary evidence supports a phased, task-specific approach to improving motor control and dynamic stability during the follow-through, where the training objective is to convert coordinated joint sequencing into reproducible deceleration strategies that protect tissue while preserving shot dispersion. Key targets are the timed eccentric activation of the lead shoulder and trunk rotators, rapid absorption across the distal kinetic chain, and minimal compensatory motion at the lumbar spine. Interventions should be anchored in measurable outcomes (e.g., variability of clubface angle at impact, deceleration impulse at the lead arm, and post-swing center-of-pressure excursions) to ensure transfer from the gym to the course.

Program content integrates complementary modalities that each address a distinct physiologic mechanism. Core components supported by the literature include:

- Strength & eccentric conditioning for hip,scapular stabilizers,and trunk rotators;

- Plyometric and ballistic drills to tune rate-of-force development for late swing deceleration;

- Proprioceptive/perturbation training to enhance reactive stability during off-axis follow-throughs;

- Task-specific transfer practice including constrained and augmented swing drills to embed timing; and

- Neuromotor retraining using feedback strategies that encourage an external focus and reduced conscious control.

Each element is dosed and progressed according to readiness and measured motor outcomes rather than arbitrary timelines.

Practical dosing and progression can be summarized within a simple operational template that coaches can adapt to skill and fitness level. Use objective thresholds (e.g., ability to perform 3×8 single-leg eccentric stepdowns with <15% knee valgus) before advancing to high-velocity deceleration drills. The table below gives exemplar prescriptions for a typical 8-12 week mesocycle:

| Exercise | Dose | Primary Target |

|---|---|---|

| Single-leg eccentric step-down | 3×8, 2-3×/wk | Hip/trunk eccentric control |

| Medicine-ball rotational decel throws | 4×6, plyometric week | Rate of force absorption |

| Reactive balance with perturbation | 3×40s, 2×/wk | Proprioceptive stability |

Progression criteria should be both capacity-based and outcome-based to ensure safe transfer to fast, golf-specific swings.

Motor-learning strategies that maximize retention and transfer emphasize variability, appropriate feedback frequency, and an external attentional focus. Evidence favors randomized or blocked-random practice schedules over massed, repetitive rehearsals for complex multi-joint sequences, and recommends faded augmented feedback (e.g., video or shot outcome) to prevent dependency. Cueing should prioritize outcome-relevant sensations (e.g., “feel the club slow through impact” rather than “contract the rotator cuff”) and combine deliberate error-augmentation drills to expand the athlete’s adaptive solution space for follow-through deceleration.

Risk mitigation and monitoring are integral to protocol design: incorporate periodic load-response assessments (e.g., countermovement jump asymmetry, isometric mid-thigh pull, shoulder eccentric torque) and on-course variability measures. Return-to-performance criteria should require consistent deceleration mechanics under fatigue and during off-target perturbations. integrate recovery strategies (progressive eccentric exposure, soft-tissue modulation, and graded volume reduction) to minimize overload-maintaining the dual priorities of optimizing shot consistency and preserving long-term musculoskeletal integrity.

Practical Measurement Techniques and Assessment Tools for Coaches and Clinicians

Measurement for golf follow-through should explicitly differentiate kinematic description from dynamic causation: **kinematics** quantifies motion (positions, velocities, angles) without invoking forces, whereas **dynamics** interprets those motions in terms of net moments and ground reaction forces. Coaches often prioritize kinematic sequencing and timing for performance cues, while clinicians require dynamic parameters to evaluate tissue load and injury risk. This conceptual distinction guides tool selection and determines whether assessments emphasize temporal‑spatial metrics or force/torque estimation for clinical decision-making.

recommended instrumentation spans laboratory and field tiers. Core options include:

- Optical motion capture (marker-based) for gold‑standard 3D segment kinematics;

- Inertial measurement units (IMUs) for portable angular velocity and orientation tracking;

- Force plates / pressure mats for ground reaction forces (GRF) and center of pressure (COP);

- High‑speed video for qualitative sequencing and manual angle extraction;

- Surface electromyography (sEMG) for muscle activation timing and amplitude.

selection should balance validity,portability,cost,and the clinical question (performance vs. tissue load).

Practical measurement settings and minimum technical specifications can be summarized to aid procurement and protocol design:

| Device | Minimum Sampling Rate | Primary Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Optical motion capture | 200-500 Hz | Capture rapid trunk and wrist rotations |

| IMU (orientation/gyro) | 200-1000 Hz | Angular velocity fidelity; reduce aliasing |

| Force plate | 1000 Hz | Accurate GRF peaks and impulse |

| sEMG | 1000-2000 Hz | Muscle onset and frequency content |

Data processing and interpretation require rigorous attention to filtering, calibration and integration artifacts. Low‑pass Butterworth filtering should be tuned to preserve swing harmonics while removing noise; accelerometer integration to obtain displacement must account for drift and baseline offsets-techniques such as zero‑velocity updates or constrained kinematic models reduce integration error. When deriving equations of motion for inverse dynamics,separate kinematic variables and apply appropriate boundary conditions; as in classical mechanics,correct variable separation and integration practices are essential to avoid propagation of systematic error into estimated joint moments.

For practical clinical workflows prioritize reliability and actionable metrics: establish intra‑ and inter‑rater reliability for marker/IMU placement, report minimal detectable change for key variables (e.g., peak trunk angular velocity, lead‑hip extension angle), and maintain normative comparison bands for skill levels. Quick screening batteries can combine a high‑speed video ballistic test, a single IMU rotation trial, and a force‑plate single‑leg landing to triage athletes for full biomechanical lab assessment.Above all, document **validity**, **reliability**, and **clinical relevance** for each metric so coaches and clinicians can translate kinematic and neuromuscular data into targeted intervention plans.

Q&A

Q: What is the scope and primary objective of the article “Kinematics and Neuromuscular basis of golf Follow‑Through”?

A: The article examines the biomechanical and neuromuscular mechanisms that govern the follow‑through phase of the golf swing. Its objectives are to (1) describe the kinematic sequencing and intersegmental momentum transfer that occur after ball impact, (2) characterize the neuromuscular strategies-notably active deceleration and eccentric control-that athletes use to dissipate residual energy safely and consistently, and (3) identify implications for shot accuracy, performance consistency, and injury prevention.

Q: Why focus on the follow‑through rather than only on the downswing and impact?

A: Although peak performance is often associated with the downswing and impact, the follow‑through is integral to (1) completing the energy transfer initiated earlier in the swing, (2) stabilizing the body and implement after high‑velocity motion, and (3) modulating residual forces that influence clubface orientation and post‑impact ball behavior. Moreover, follow‑through mechanics are associated with repetitive load patterns implicated in overuse injuries; understanding them informs training and rehabilitation.

Q: What kinematic features define the follow‑through?

A: Key kinematic features include:

– Continued proximal‑to‑distal sequence: pelvis rotation leads thorax rotation, followed by shoulder/arm motion and finally the club.

– Peak angular velocities: while the clubhead reaches maximum speed at or just before impact, sequential peaks of segmental angular velocity continue into early follow‑through.

– Intersegmental energy transfer: rotational momentum propagates from larger proximal segments to distal segments,and then must be dissipated.

– Center of mass and base‑of‑support adjustments: weight transfer onto the lead leg and postural adjustments stabilize the body during deceleration.

Q: What neuromuscular control strategies are employed during follow‑through?

A: The follow‑through relies heavily on active neuromuscular control, including:

– Eccentric muscle actions: muscles acting across the shoulder, elbow, and trunk engage eccentrically to absorb and control rotational and translational energy.

– Timing of muscle activation: coordinated bursts and dampening activations (muscle synergies) occur to sequence deceleration from proximal to distal segments.

– Feedforward and feedback control: anticipatory (feedforward) activation shaped by swing tempo and conditioning combines with rapid feedback corrections to manage perturbations or mis‑hits.

– Interlimb coordination: lower‑body musculature (hip extensors/rotators, knee stabilizers) provides a mechanical foundation for upper‑body deceleration.

Q: Which muscles are most critically important for deceleration and injury prevention in the follow‑through?

A: muscles commonly implicated include:

– Trunk rotators and extensors (obliques, multifidus, erector spinae) for controlling axial rotation and lumbar shear.

– Shoulder stabilizers (rotator cuff, deltoid) for controlling humeral motion and protecting the glenohumeral joint.

– Elbow and forearm muscles (biceps, triceps, wrist flexors/extensors) for controlling elbow extension/flexion and wrist position, particularly against valgus/varus stresses.

– Hip and lower‑limb muscles (gluteus maximus/medius, hamstrings, quadriceps) for weight transfer, pelvic control, and ground reaction force modulation.

Q: How are kinematics and neuromuscular activity measured in such studies?

A: Typical measurement methods include:

– 3D motion capture (optical marker systems) sampling commonly 200-500 Hz to quantify joint angles, angular velocities, and segmental kinematics.

– Force platforms to record ground reaction forces and moments for analyzing weight transfer and external loading.

– Surface or fine‑wire electromyography (EMG) sampled at 1,000-2,000 Hz to quantify timing and amplitude of muscle activation; signals usually processed with rectification and smoothing and normalized to maximum voluntary contractions.

– Inverse dynamics to compute joint moments and intersegmental forces from kinematic and kinetic data.

– Inertial measurement units (IMUs) for field‑based kinematic monitoring when lab systems are not available.

Q: What analytical approaches are used to quantify intersegmental momentum transfer and deceleration?

A: Analysts commonly use:

– Time‑series analysis of segmental angular velocity and acceleration to establish sequencing and peak timings.

– Inverse dynamics to estimate joint moments, powers, and net muscular demands during deceleration.

– Cross‑correlation or phase analysis to assess coordination between segments and muscles.

– Statistical modeling (e.g., mixed effects models) to relate kinematic/neural variables to outcome measures such as clubface orientation, dispersion, or reported pain.

– Principal component or synergy analysis to identify common muscle activation patterns underlying deceleration.

Q: What are the main findings regarding timing and sequencing during follow‑through?

A: Summarized, the findings indicate:

– the proximal‑to‑distal pattern characteristic of the downswing continues through impact and into follow‑through, but with a shift toward energy dissipation.

– Peak angular velocities of proximal segments generally precede those of distal segments; though, deceleration onset typically begins at proximal segments (trunk/pelvis) and propagates distally via eccentric muscle action.

– Consistent timing and reduced variability of segmental sequencing in follow‑through are associated with greater shot accuracy and reproducibility.

Q: How does follow‑through control relate to shot accuracy and consistency?

A: Accurate and consistent follow‑through control contributes to:

– Stabilizing clubface orientation immediately after impact, reducing small perturbations that can affect ball trajectory.

– Minimizing post‑impact torques transmitted back through the club and player that could reflect pre‑impact inconsistencies.

– Reduced variability in segmental sequencing and muscular timing is statistically associated with tighter shot dispersion in observational and experimental studies.

Q: What injury mechanisms are associated with deficient follow‑through mechanics?

A: potential injury mechanisms include:

– Excessive eccentric loading of shoulder or elbow structures due to poor deceleration timing or inadequate muscular capacity, increasing risk for rotator cuff tendinopathy, medial elbow valgus overload, or tendon strains.

– High rotational shear or asymmetric loading of the lumbar spine if trunk deceleration is insufficient or if lower‑limb support is compromised.- Repetitive microtrauma from cumulative high‑velocity deceleration demands leading to overuse conditions in the wrist, elbow, shoulder, or lower back.

Q: What training or intervention strategies does the article recommend?

A: Practical recommendations include:

– Eccentric strengthening: targeted eccentric training for shoulder, elbow, trunk, and hip musculature to improve capacity to absorb energy.

– Neuromuscular control drills: swing drills emphasizing controlled deceleration and balanced follow‑through (e.g., slow‑motion swings, impact‑to‑finish holds).

– Strength and power training for the kinetic chain to optimize energy transfer while maintaining control.

– Motor learning cues and tempo training to enhance feedforward timing and reduce variability.- Use of biofeedback (EMG or IMU) for technique correction and monitoring fatigue‑related changes in deceleration patterns.

Q: What limitations should readers consider about typical studies on follow‑through biomechanics?

A: Common limitations include:

– Sample characteristics: many studies use small samples, often limited to either skilled or recreational golfers, reducing generalizability.

– Laboratory setting: motion capture lab conditions may alter natural swing mechanics compared with on‑course swings.

– Measurement limitations: surface EMG is subject to crosstalk and may not capture deep muscle activity; inverse dynamics assumes rigid segments and can be sensitive to marker placement errors.

– Cross‑sectional designs: without longitudinal or intervention studies, causality between mechanics and injury or performance is difficult to establish.Q: What are key directions for future research?

A: Recommended avenues include:

– Longitudinal and intervention trials testing whether targeted eccentric and neuromuscular training improves follow‑through control and reduces injury incidence.

– High‑fidelity musculoskeletal modeling and simulation to estimate tissue‑level loads and predict injury risk.

– Field‑based validation using wearable sensors to study follow‑through in ecological settings and across fatigue states.

– Investigation of neural control mechanisms (e.g., cortical and spinal contributions) to anticipatory and feedback components of deceleration.

– Individualized modeling to relate anatomical and functional variability to optimal follow‑through strategies.Q: How can coaches and clinicians apply these findings in practice?

A: Request points:

– Assess follow‑through as a diagnostic window into a player’s ability to control residual energy-look for uncontrolled “snapping” or truncation of follow‑through.

– Incorporate eccentric exercises and deceleration drills into periodized programs, prioritizing muscle groups identified as key stabilizers.- Use objective monitoring (IMUs, force platforms, simple video analysis) to detect changes in sequencing or variability that may precede injury.

– Emphasize consistent tempo and balanced finishes in technical coaching to promote robust neuromuscular timing.

Q: Are there practical markers observable without laboratory equipment that indicate poor follow‑through control?

A: Yes.Observable signs include:

– Abrupt or jerky termination of the swing with minimal balanced finish.

– Excessive lateral sway or collapse onto the lead leg immediately after impact.

– Frequent early release or “flicking” of the wrists indicative of poor distal control.- Recurrent or worsening upper limb or low back discomfort correlated with certain swing endings.

Q: What is the overall clinical and performance meaning of understanding follow‑through biomechanics?

A: Understanding follow‑through biomechanics links the physics of energy transfer to the physiology of muscular control: optimizing follow‑through supports shot accuracy and repeatability while reducing potentially harmful loads on musculoskeletal tissues. This dual focus makes follow‑through an important target for coaching, strength and conditioning, and clinical management of golf‑related injuries.If you would like, I can: (1) generate a short checklist for coaches to screen follow‑through mechanics on the course, (2) draft a sample protocol for measuring follow‑through kinematics and EMG in a lab, or (3) summarize specific eccentric strength exercises recommended for key muscle groups. Which would you prefer?

Key Takeaways

this review has synthesized current evidence on the kinematic and neuromuscular determinants of the golf swing follow-through, emphasizing how coordinated joint sequencing, efficient momentum transfer, and targeted active deceleration contribute to shot accuracy, consistency, and tissue protection. Empirical kinematic profiles together with electromyographic and kinetic data underline that precise timing of segmental rotations and graded eccentric muscle activity are central to managing residual club and body momentum while preserving alignment of the target line. These mechanisms operate in concert with sensorimotor processes-proprioception, feedforward planning, and feedback-driven corrections-that together shape outcome variability and injury risk.

from a translational perspective, the findings point to practical strategies for coaches, strength and conditioning professionals, and clinicians: train multi-segment coordination rather than isolated joints, emphasize eccentric control and energy-absorbing capacity of the shoulder, trunk, and lead lower limb, and incorporate task-specific drills and perturbation-based practice to enhance adaptive neuromuscular responses. Biomechanically informed coaching cues and progressive load management may concurrently improve performance and reduce the likelihood of overuse and acute injuries associated with excessive distal deceleration demands.

Methodological limitations of the existing literature-heterogeneous study designs, small samples, and limited longitudinal and in-field assessments-highlight opportunities for future research. Longitudinal interventions, high-fidelity modeling that includes higher-order kinematic descriptors (e.g., jerk) and muscle-tendon dynamics, integration of wearable sensor systems for ecologically valid measurement, and investigation of individual variability in motor strategies will be important to refine mechanistic understanding and to personalize training and rehabilitation protocols.

Collectively, a rigorous, multidisciplinary approach that links detailed biomechanical quantification with neuromuscular assessment and pragmatic training interventions holds promise for optimizing follow-through mechanics. Advancing this agenda will not only deepen scientific insight into the motor control of complex ballistic actions but also deliver evidence-based practices that enhance performance and safeguard the musculoskeletal health of golfers across skill levels.

Kinematics and Neuromuscular Basis of Golf Follow-Through

Understanding the golf follow-through from both a kinematics (motion) and neuromuscular (muscle control) viewpoint gives players and coaches actionable insight for improving accuracy, maximizing clubhead speed, and reducing injury risk. Below you’ll find science-backed breakdowns of joint sequencing, momentum transfer, active deceleration strategies, and practical drills to make your follow-through more consistent and resilient.

why the Follow-Through Matters in the Golf Swing

- Accuracy: A controlled follow-through reflects correct impact mechanics and helps minimize face rotation through impact.

- Power transfer: Proper sequencing through the follow-through indicates efficient kinetic chain transfer from legs and hips into the clubhead.

- Injury prevention: Active neuromuscular control during deceleration reduces stress on the shoulders, elbows, and lower back.

- Feedback loop: The finish position gives immediate kinesthetic feedback-good finishes usually follow good strikes.

Core Kinematic Concepts Applied to Golf Follow-Through

Kinematics describes motion without reference to forces.In golf, that means tracking positions, angles, angular velocities, and sequencing through the swing and follow-through. Useful kinematic variables include:

- Angular velocity of hips, thorax, and shoulders (rpm / degrees per second)

- Relative timing (lead-lag) between pelvis and torso rotation

- Clubhead speed profile through impact into the follow-through

- Center of pressure and weight transfer path across the feet

Key kinematic principles

- Proximal-to-distal sequencing: Rotational power starts from the ground and moves up – feet → hips → torso → shoulders → arms → club.

- Conservation of angular momentum: A smooth follow-through indicates appropriate momentum transfer and minimal energy leaks prior to impact.

- deceleration phase: After impact the body must reduce club angular velocity safely; the way this happens reveals neuromuscular control quality.

Neuromuscular Basis: How Muscles Control the Follow-Through

The neuromuscular system coordinates rapid, timed contractions and relaxations across many muscle groups. For a golf follow-through this coordination performs two critical jobs: efficient power transfer and controlled deceleration.

Primary muscle groups involved

- Lower body: Gluteus maximus and medius, adductors, quadriceps – provide ground reaction force and hip rotation.

- core and trunk: External/internal obliques, multifidus, rectus abdominis – stabilize pelvis-torso separation (X-factor) and transfer rotation.

- Shoulder girdle: Rotator cuff, deltoids, trapezius – help guide arm path and decelerate the club after impact.

- Forearm/wrist: Flexors/extensors – control grip, release, and fine face orientation through impact.

Neuromuscular timing & motor control

electromyography (EMG) studies show sequential burst patterns: hip extensors activate before trunk rotators, which in turn activate before shoulder and arm muscles. Efficient golfers display well-timed low-to-high muscle activation that minimizes co-contraction (simultaneous opposing muscle activation) at the wrong times. This reduces energy losses and decreases joint loads during the follow-through deceleration.

Joint Sequencing and Movement Patterns

Quality of follow-through frequently enough mirrors upstream sequencing quality. Below is a simplified flow of optimal kinematic sequencing:

| Stage | Goal | Key Motion |

|---|---|---|

| Address → Backswing | Store elastic energy | Coiling of hips and torso, weight to trail leg |

| Downswing → Impact | Transfer momentum to clubhead | Hip rotation leads, torso follows, hands deliver club |

| Early Follow-Through | Continue momentum, maintain face control | Extension through hips and wrists, hip rotation continues |

| Late Follow-Through (Deceleration) | Absorb & dissipate energy safely | Active shoulder/arm deceleration, trunk stabilization |

Active Deceleration: The Unsung Hero

After ball impact the clubhead still carries important velocity. Without active neuromuscular braking, that energy must be absorbed by passive structures (ligaments, joint capsules), increasing injury risk. Key points:

- Controlled eccentric contractions in the rotator cuff and scapular stabilizers slow arm rotation.

- Core musculature counters trunk rotation to avoid excessive shear in the lumbar spine.

- Proper weight transfer to the lead leg creates a stable base for deceleration.

common faults related to poor deceleration

- Arm-dominant finish (flying elbow): insufficient core/hip engagement → reduced control and possible shoulder strains.

- Over-rotation of the trunk without hip follow-through → lumbar shear and lower-back pain.

- Stiff wrists/forearms → increased elbow loading (medial epicondylitis / ”golfer’s elbow”).

Practical Drills to Improve Follow-Through Mechanics

These drills focus on timing, sequencing, and safe deceleration. Use them regularly in warm-ups and practice sessions.

Drill 1: Step-and-Drive (sequencing)

- Start with a small step toward the target as you start your downswing.

- Focus on initiating rotation with the hips and letting the torso and arms follow.

- Goal: Feel the proximal-to-distal energy flow and a smooth follow-through.

Drill 2: Slow-Motion to Fast-Motion (motor control)

- Begin swings at 30% speed,gradually increase to full speed over 10-15 reps.

- Concentrate on consistent finish positions and controlled deceleration after impact.

- Goal: Train neuromuscular timing without compensatory tension.

Drill 3: Club Drop & Catch (eccentric control)

- From a full finish, have a partner gently pull the club head away; resist with controlled muscle action.

- Alternatively, hold the club and practice slow controlled reversals to simulate deceleration loads.

- Goal: Build eccentric strength in shoulders and forearms.

Drill 4: Medicine Ball Rotational Throws (power & sequencing)

- Explosive throws mimic hip-to-shoulder rotational sequencing and encourage transfer into the follow-through.

- Perform rotational throws to the target side to train core, hips, and trunk timing.

Golf Swing Metrics to Track Your Follow-Through

Recording and analyzing simple metrics helps quantify improvements and spot injury risk:

- Clubhead speed at impact and how quickly it decays (follow-through speed curve)

- Pelvis-to-torso peak angular velocity difference (X-factor dissipation)

- Finish position symmetry and stability (eye-level, balanced weight over lead foot)

- contact quality and dispersion (accuracy)

Injury Prevention Strategies for a Safe Follow-Through

Combine biomechanical training, neuromuscular conditioning, and load management:

- Strengthen rotator cuff and scapular stabilizers to manage deceleration forces.

- Develop hip mobility and glute strength to produce rotation without lumbar overcompensation.

- Incorporate eccentric-focused exercises for forearm and wrist tolerance.

- Use progressive overload in practice-avoid constant maximum-power full swings during high-volume range sessions.

case Study: Translating Kinematic Insight into Performance Gains

player A, a mid-handicap golfer, suffered inconsistent ball striking and intermittent low-back discomfort. Motion capture showed early trunk rotation and inadequate hip drive, resulting in a late arm-dominant follow-through and excessive lumbar shear. intervention included:

- Targeted medicine-ball hip drives to re-time pelvis initiation

- eccentric rotator-cuff and thoracic mobility work to control shoulder deceleration

- Structured practice emphasizing step-and-drive and slow-to-fast swings

Outcome (12 weeks): improved dispersion by 22%, reduced perceived back pain during play, and a more balanced finish position with visible hip rotation through the ball.

First-hand Experiance: Coaches’ Tips for Reinforcing a Good Follow-Through

From a coaching vantage, small cues and consistent feedback accelerate learning:

- Use finish-hold drills-have golfers hold their finish for 3-5 seconds to ingrain balance and deceleration control.

- Video record swings from down-the-line and face-on angles to check sequencing and weight shift.

- Encourage rhythmic breathing and tension management-too much upper-body tension ruins sequencing.

- Progress drills from slow to full speed; consistency at slower speeds predicts better transfer to full power swings.

SEO-Friendly Keywords Incorporated Naturally

Throughout this article, vital search terms were used to improve discoverability: golf follow-through, golf swing mechanics, clubhead speed, follow-through drills, golf accuracy, swing sequencing, neuromuscular control, injury prevention in golf, rotational power, and follow-through mechanics.

Quick Reference: Troubleshooting Common Follow-Through Problems

- Problem: Early release / casting – fix: Strengthen core timing, practice slow-to-fast swings.

- Problem: Over-rotation of torso – Fix: Improve hip mobility and drill step-and-drive to lead with hips.

- Problem: Stiff finish with limited shoulder follow-through – Fix: Add thoracic mobility and eccentric shoulder work.

- Problem: Pain during follow-through – Fix: Reduce practice load, seek movement screening, and address muscular imbalances.

recommended Weekly Practice Plan to Improve Follow-Through (Sample)

| Day | Focus | Duration |

|---|---|---|

| Mon | Mobility & eccentric shoulder work | 30-40 min |

| Wed | Sequencing drills (step-and-drive, med ball) | 45 min |

| Fri | Controlled range session (slow → full swings) | 60 min |

| Sun | On-course simulation, focus on finish and balance | 90 min |

Use these principles to build a follow-through that supports both consistency and longevity. The intersection of kinematics and neuromuscular control is where repeatable swing mechanics and safe play meet-refine both and you’ll see gains in distance, accuracy, and resilience on the course.