Teh golf swing is a complex, multi-joint motor skill in which millisecond timing, intersegmental coordination, and force application converge to determine performance and injury risk.Contemporary biomechanical research has delineated key determinants of effective swings-temporal sequencing of segments, optimal angular velocities, ground-reaction force generation, and appropriate energy transfer from torso to club-while motor-learning studies clarify how practice structure, feedback, and variability influence skill acquisition. Integrating these lines of evidence provides a principled basis for coaching interventions that transcend anecdote and tradition.

This article synthesizes peer-reviewed biomechanics, motor-control, and coaching literature to derive practical, evidence-based techniques applicable across the spectrum of golfers, from novice to elite. Emphasis is placed on measurable performance variables (e.g., clubhead speed, ball speed, launch conditions, kinematic sequencing) and on readily implementable assessment protocols using common tools (video analysis, launch monitors, and simple on-course tests). We also evaluate training variables-drill design, feedback modalities, practice schedules, and physical conditioning strategies-that have demonstrated efficacy for improving consistency, power, and injury resilience.Readers will find a structured framework for translating theory into practice: baseline assessment metrics, prioritized corrective strategies for common faults, progressive drill sequences tailored to skill level, and objective criteria for monitoring improvement. By bridging mechanistic insights with applied coaching methods, the material aims to enable coaches, players, and practitioners to make informed, measurable decisions that optimize performance while minimizing undue risk.

Biomechanical Foundations of an Efficient Golf Swing: Kinematic Sequencing, Joint Loading, and recommended Target Ranges

Efficient power transfer in the golf swing depends on a coordinated, proximal-to-distal kinematic sequence in which the pelvis initiates rotation, followed by the thorax, then the upper arms and hands, and finaly the clubhead. For practical coaching, target rotational ranges are useful: aim for a pelvic rotation of approximately 30-45° on the backswing and a shoulder turn of approximately 80-100°, producing an X‑factor (shoulder-pelvis separation) commonly targeted between 20° and 50° depending on mobility and skill level; elite players frequently approach the upper end of this range. From a biomechanical safety perspective, minimize excessive lateral spine bending and uncontrolled extension becuase these increase compressive and shear loads on the lumbar spine; instead, prioritize a stable spine angle and torque transfer through the hips and core.In course play, translate these targets into on-course feel by checking whether longer clubs retain ball-direction control when the X‑factor and rotation are within target ranges-if dispersion increases, reduce shoulder turn by 10-20% and re-evaluate balance and sequencing.

- Setup checkpoints: balanced 50/50 weight, neutral spine angle, ball position appropriate to club (e.g.,centre-heel for irons,forward for driver).

- Mobility goals: aim for symmetrical thoracic rotation that allows a shoulder turn near 90° and hip rotation to support 30-45° of pelvic turn.

To convert kinematic principles into repeatable mechanics, practice a timed sequence: initiate the backswing with a controlled lateral weight transfer and hip coil, hold the wrist hinge while the torso continues to rotate, then start the downswing with a purposeful uncoiling of the hips toward the target-this creates the desirable lag and a late, powerful clubhead release. For measurable targets, use weight-distribution benchmarks: address ~50/50, top of backswing ~60/40 (trail/lead), and impact ~80/20 (lead/trail). Drills that reinforce this timing include the step-through drill (promotes ground reaction force and weight shift), the pump drill (builds correct sequencing and lag), and the medicine‑ball rotational throw (develops explosive proximal-to-distal transfer). For beginners, slow-motion reps with a metronome (e.g., 4:1 tempo backswing:downswing) build neural patterns; for advanced players, use high-speed video or a launch monitor to target consistent peak pelvic angular velocity and clubhead speed while keeping dispersions (side-to-side) within desired yardage for each club.

- Practice drills:

- Step-through drill for weight shift and ground force.

- Pump drill (stop at hip-clearance) to feel correct sequencing.

- Putting gate and distance-ladder drills for transferable tempo control.

- Troubleshooting common errors:

- Early arm release → strengthen lag with half‑swings and impact bag work.

- Over-rotation of shoulders with fixed hips → do resisted hip-turn drills to re-establish pelvis initiation.

- Lower-back soreness → reduce lateral bend, increase thoracic mobility and core stability exercises.

integrate these mechanical improvements with short-game technique, equipment choices, and on-course strategy to improve scoring. For putting, prioritize a repeatable shoulder-driven arc (pendulum motion) and measure stroke length against distance control drills; note that anchoring the club is not permitted under post‑2019 Rules of Golf, so train a free-standing stroke. For driving,select shaft flex and loft that allow a clean launch angle (typically 10-14° launch for many recreational players) while preserving the sequencing targets above; when wind or wet conditions change traction,shorten the backswing and maintain the same sequencing to reduce dispersion. Establish practice plans with weekly measurable goals (e.g., reduce three-putts by 50% in six weeks, or increase fairways hit from 40% to 55% in eight weeks) and adapt for physical constraints by offering option techniques-such as a wider stance and more shoulder-driven swing for players with limited hip rotation. In addition, incorporate brief pre-shot routines and visualization to link the technical plan to shot selection, ensuring that biomechanical improvements translate directly into smarter course management and lower scores.

Evidence Based Assessment Protocols for Swing Evaluation: Motion Capture Metrics, Launch Monitor Variables, and Interpreting Results

Begin by standardizing a laboratory-style capture protocol so that motion-capture and launch-monitor data are comparable over time. First, perform a static calibration with the golfer in address using a club with known length, then record a minimum of 10 swings after a standardized warm-up and ball/tee setup; calculate metrics from the mean of the best five swings (highest consistency) and report standard deviation to assess repeatability (target SD <5% for clubhead speed). Motion-capture should sample at ≥240 Hz and track pelvis, thorax, lead and trail wrists, and a marker on the clubhead to derive kinematic-sequence timings, peak angular velocities, and segmental rotation. Key motion metrics to record are X‑factor (shoulder-to-pelvis separation at the top), peak pelvic rotation speed, upper-torso rotation, swing-plane angle, and wrist-cocking angles; aim for typical ranges of shoulder turn 80-100° (men) and pelvic turn 45-60° as baseline targets, with lower thresholds for smaller-stature players. To ensure useful coaching feedback, include a short checklist for setup and calibration:

- Calibration pose: neutral address with club across toes;

- Marker set: bilateral ASIS/PSIS for pelvis, C7/T8 for thorax, radial styloid for wrists, clubhead tip;

- sampling: 240-500 Hz capture rate and synchronized launch monitor (radar/photometric) timestamps;

- Data protocol: warm-up, 10 swings, isolate best 5 for reporting, include trial-to-trial SD.

These controls reduce noise and allow coaches to link specific kinematic faults to ball-flight signatures on the course.

Next,integrate launch-monitor variables with the biomechanical output to create interpretable cause-effect relationships. Record clubhead speed, ball speed, smash factor, launch angle, total spin (backspin and sidespin), attack angle, club path, and face-to-path; such as, a driver smash factor <1.40 typically indicates poor center-face contact or excessive loft at impact, whereas a target smash factor for efficient contact is ~1.45-1.50. Use concrete windows to diagnose problems: a low launch (8°) with high spin (> 3,000 rpm) often signals a steep,negative attack angle combined with an excessively closed face at impact; conversely,excessive launch (> 14°) with low spin (< 1,500 rpm) can mean an overly positive attack angle or too much dynamic loft. To translate diagnostics into corrective practice, apply short, specific drills:

- Impact-bag drill: promotes forward shaft lean and center contact for improving smash factor and reducing excessive loft;

- Alignment-stick plane drill: place an alignment stick along the shaft line to ingrain a functional swing plane and correct steepness;

- Half‑to‑three‑quarter swings with metronome or weighted club: develops proper kinematic sequence and increases clubhead speed safely.

By correlating the motion-capture sequence (e.g., delayed torso peak vs.early hand release) with launch numbers (e.g., low ball speed, high spin), coaches can prescribe focused technical cues and equipment adjustments-such as altering driver loft/shaft flex or tee height-to achieve targeted ball-flight windows for a given player.

interpret results within on-course strategy and measurable improvement plans that accommodate skill level, physical capacity, and playing conditions. Begin with objective, time-bound goals-for example, a beginner might aim to increase driver clubhead speed from 80 to 88 mph over 12 weeks through a combination of technique (weight-shift drill, hip-rotation sequencing) and physical training, while a low handicap player may target a 200-500 rpm reduction in driver spin via mechanical changes (attack angle, dynamic loft) or equipment tuning (loft/shaft/bounce): remember that all clubs must conform to USGA equipment rules when modified. Then create a progressive practice plan that blends range work,short-game control,and situational on-course play:

- range sessions: 30 minutes of targeted swing-drills (impact bag,alignment stick) followed by 30 minutes of launch-monitor feedback (10-shot blocks,record means);

- Short game: clock-face wedge distance control and putting gate drills to convert improved strike into lower scores;

- On-course application: simulate windy or firm conditions by practicing lower-launch,lower-spin shots and decision-making exercises (club selection to play for preferred bounce/roll).

Also address common faults and corrections-early extension (use wall-drill to maintain spine angle), casting (towel-under-arm to maintain wrist lag), and over-rotation (tempo-metric drills)-and integrate mental strategies such as process goals, a concise pre-shot routine, and numeric thresholds to guide club choice under pressure. In sum, use the combined data stream of motion capture and launch-monitor outputs to produce quantified interventions, repeatable practice progressions, and course-management adjustments that translate technical improvements into reliable scoring gains.

Applying Motor Learning Principles to Practice: Recommended Feedback Schedules, Variability, and Session structure

Begin practice sessions by applying evidence-based motor learning schedules: start with a high frequency of knowledge of performance (KP) feedback when introducing or modifying a technical element (such as, correcting early extension or an open clubface). Initially use blocked practice (sets of 8-12 repetitions of the same swing or short-game motion) to isolate the motor pattern, providing immediate, descriptive feedback such as video playback or coach verbal cues. For example, teach a driver swing sequence with a progression of half-swings → three-quarter swings → full swings, aiming for a shoulder turn ≈ 90° and hip turn ≈ 45°; check impact with the goal of shaft lean ~5-10° forward for irons and a slightly positive attack angle of +2-4° for the driver. Then, transition to faded feedback (reduce KP frequency gradually) and increase knowledge of results (KR) timing (delayed score/dispersion feedback) to enhance retention and transfer. To consolidate learning, implement bandwidth feedback-only intervene when the error exceeds a tolerance (such as, when shot dispersion exceeds ±15 yards for a 7-iron or when face angle at impact exceeds ±3°)-which encourages self-correction and preserves the golfer’s intrinsic error-detection processes.

Next,structure sessions with explicit time blocks and repeatable metrics,moving from controlled technique work to variable,game-like practice.A recommended session might include: 10-15 minutes warm-up (mobility, dynamic stretches, gradual club progression), 25-40 minutes technical block (blocked reps focusing on one mechanical target: a set of 40-60 swings with video/KP), 20-30 minutes variable practice (randomized club and lie selection, simulated course shots), and 10-15 minutes short-game and putting under pressure. Use specific rep counts and rest intervals: perform sets of 8-12 repetitions with 60-120 seconds rest between sets for technical work and shorter rest for endurance drills. Include these practical drills and checkpoints:

- Impact-bag or tee drill to train forward shaft lean and compress irons.

- Gate drill for squaring the clubface at impact in the short game.

- One-club challenge on the range to develop trajectory control and course management.

- Three-spot putting (make 8/12 from 6 ft, 12 ft, 18 ft) to quantify improvement.

Also pay attention to equipment and setup: ensure correct lie angle,check loft/bounce on wedges for turf interaction,and use a ball with appropriate compression for feel; common mistakes like casting,over-gripping,or insufficient shoulder turn can be identified and corrected with targeted drills and measurable goals (e.g., reduce 7-iron lateral dispersion to ±10 yards in 6 weeks).

integrate variability, decision-making, and mental strategies to ensure transfer to the course: practice in different wind conditions, from tight and plugged lies, and on uphill/downhill lies to build adaptable motor programs. Use random practice sessions that mix clubs, targets, and lie angles to simulate on-course demands; for instance, perform a 60-shot sequence alternating tee shots, approach shots of 100-160 yards, and pressure chips where a missed par-save results in a repeat attempt-this builds resilience and situational judgment. Combine feedback schedules with learner-centered choices: allow the player to request video review (self-controlled feedback improves motivation and retention) and employ an external focus cue such as “feel the clubhead release toward the target” rather than internal cues about body parts. For different learning styles provide multiple modalities-visual (slow-motion video), kinesthetic (impact-bag), and auditory (metronome set to a 3:1 backswing-to-downswing tempo)-and emphasize pre-shot routine, breathing control, and visualization for stress management. In short,alternate technical blocks with variable,decision-rich practice,monitor progress with objective metrics,and apply rules-aware course strategies (e.g., playing the ball as it lies, selecting conservative targets to avoid penalty areas) so that technical improvements reliably translate into lower scores and smarter on-course play.

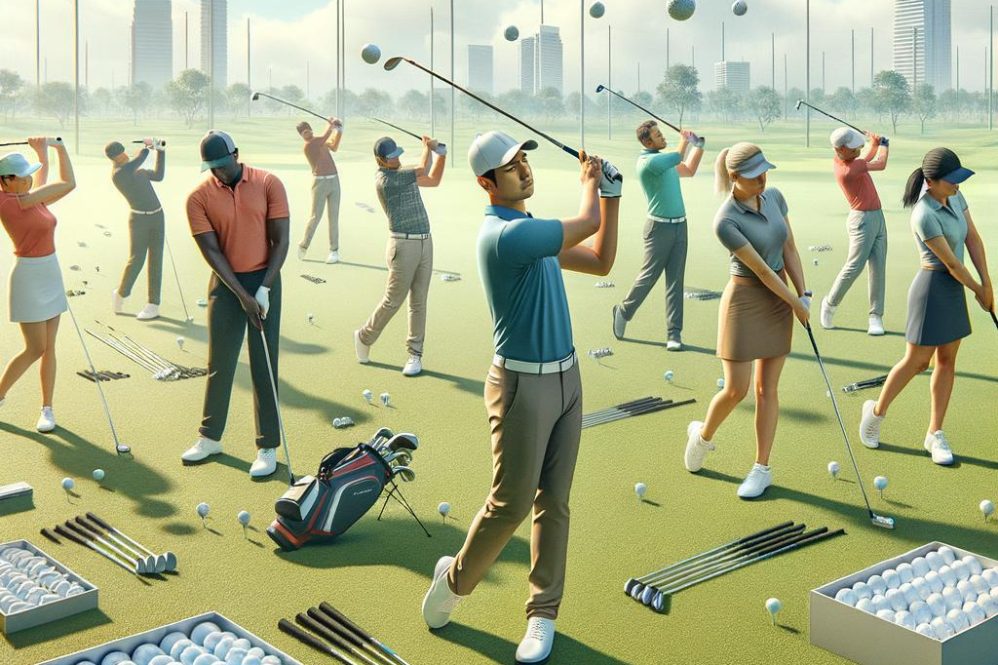

Technical interventions by Skill Level: specific Drills and Coaching Cues for Novice, Intermediate, and advanced Players

For beginners, begin by prioritizing reliable fundamentals that create a repeatable motion: grip, stance, alignment and a balanced finish. Establish a pre-shot routine of three steps (visualize target, align clubface, set feet) to reduce decision noise on the course. At setup, emphasize 50/50 weight distribution, a neutral grip (V’s pointing to the right shoulder for right‑handers), and spine tilt of approximately 5° toward the target so the swing plane is consistent; these measurements are scalable for different body types.To develop contact and path, use these drills and checkpoints:

- Gate drill (two tees or alignment rods) to teach inside‑out path and square impact;

- Impact bag to feel forward shaft lean and proper compression on shorter clubs;

- Slow‑motion 8‑to‑2 drill to ingrain a connected takeaway and shoulder turn of about 80-90° for a full swing.

Common mistakes include casting the wrists early, an overactive lower body, and inconsistent ball position; correct these with a towel‑under‑armpit drill to promote connection and a feet‑together drill to improve balance. Practice sessions should be structured as short, frequent blocks-20 minutes per basic, three to five times per week-with measurable goals such as centering 60% of short‑iron strikes on the sweet spot and reducing dispersion to within 15 yards of intended target on the range.

Progressing to intermediate players requires refining kinematic sequence and introducing situational skills: trajectory control, spin management and green approach strategy. Transition from general swing patterns to technical metrics-monitoring clubhead speed, angle of attack, and spin loft-and aim for reproducible impact conditions (e.g.,for a 7‑iron,a slightly descending strike with an attack angle of −2° to −4°). Use these practice routines to bridge mechanics and course application:

- Line‑and‑landing drill: pick a landing zone on the range and work on varying club selection to control carry and roll;

- 3‑Club swing drill: hit three different clubs to one target to learn trajectory control and shot shaping (fade/draw) by small grip and path adjustments;

- Short‑game clock drill around the green for consistent contact and distance control with wedges.

Additionally, incorporate equipment checks-verify loft and lie angles are suited to swing tendencies, choose wedge bounce based on turf/bunker conditions, and select a ball that matches spin needs on approach shots. In on‑course scenarios, teach intermediate players risk‑reward decision frameworks: when facing a reachable par‑5 into wind, quantify the trade (e.g., carry yardage vs. penalty area margin) and set a conservative target to preserve par. Measurable improvement markers include increasing greens in regulation (GIR) by 10-15% and improving proximity to hole to 25-30 feet on approach shots.

For advanced and low‑handicap players,interventions focus on micro‑adjustments,shot repertoire expansion,and strategic course management under pressure.Emphasize refined concepts such as controlling spin rate, manipulating launch angle via dynamic loft, and shaping shots on demand with precise swing plane and face‑to‑path relationships (e.g., a 2-3° face‑open relative to path for a controlled fade). Use these high‑value drills and coaching cues:

- Weighted‑club tempo drill to stabilize sequencing and maintain consistent backswing/downswing timing;

- Variable‑wind practice (use a range fan or practice into open areas) to rehearse low punch, hybrid control, and flying pin‑seeking shots with altered attack angles;

- Pressure‑simulation routines (competitive ladder or score‑streak challenges) to translate technical gains into tournament scoring under stress.

Furthermore, integrate advanced course strategy: use strokes‑gained analysis to identify largest weaknesses (e.g., approach vs. putting) and allocate practice time accordingly; when confronting a downhill green with subtle breaks, prefer a conservative putt line that removes a three‑putt risk. strengthen the mental game with a concise pre‑shot checklist and a commitment cue to reduce indecision; target stat goals such as +0.5 strokes gained per round in approach or shaving 0.2 strokes off putting via purposeful practice. These interventions, combining precise biomechanics, equipment optimization and strategic thinking, yield measurable scoring improvements and greater consistency across variable course conditions.

Drill Progressions to Improve Tempo, Axis Control, and Ball Contact: Prescriptive Exercises and Progression Criteria

Begin by establishing a reproducible setup and a measurable tempo baseline: set a neutral stance with a spine angle of approximately 15-25° (measured from vertical) and a shoulder turn target of ~90° for a full swing with hips rotating about 45°. From this posture, train a consistent tempo using a metronome (or app) with a target backswing-to-downswing ratio of 3:1 (for example, a 0.75 s backswing and 0.25 s downswing as an initial timing reference), which promotes repeatable sequencing and minimizes casting. To translate this into repeatable ball contact, first practice with short, half- and three-quarter swings, then lengthen to full swings only after achieving 30 consecutive swings at the target tempo and acceptable face contact. Useful practice drills include:

- Metronome drill – swing to the beat at 3:1 tempo, progressing from wedges to mid/long irons.

- Broomstick or alignment-rod drill – place the rod along the shaft to check plane and feel consistent wrist hinge.

- short-swing impact circles – hit 20 balls to a 10-yard target circle to build center-face contact under tempo constraints.

these drills serve all skill levels: beginners focus on rhythm and half-swings; intermediates emphasize timing under partial pressure; low handicappers refine milliseconds of transition timing and maintain tempo under fatigue.

Once tempo is controlled, prioritize axis control – the preservation of spine angle and shoulder tilt through the swing – to stabilize club path and face orientation at impact.Aim to keep lateral sway to a minimum and maintain an axis-tilt variance within ±5° from setup through impact; excessive flattening or steepening of the plane often produces hooks or slices and inconsistent turf interaction. Progression drills to develop axis control include:

- Chair/step drill – place a chair or alignment stake just behind the trail hip to discourage early extension and maintain tilt.

- Towel-under-armpits – promotes connection and synchronous body rotation rather than arm-driven motion.

- Feet-together and slow-motion swings - emphasize balance and rotational axis without lower-body overshift.

Use video feedback or a simple smartphone app to measure shoulder and hip plane at address, top-of-backswing, and impact; progress when videos show consistent axis angles and when turf patterns (divot start and length) show a repeatable low point for irons (generally just after the ball). On-course, apply axis control to punch shots under tree limbs or to hold a lower trajectory into firm greens by slightly reducing shoulder turn while keeping axis tilt stable.

couple tempo and axis control with explicit impact and spin-management work to improve ball contact and scoring. Target specific impact metrics depending on the club: for most players a negative attack angle of -4° to -6° with short irons encourages crisp,downward contact and controlled spin,while drivers often benefit from a slight positive attack (e.g., +1° to +3°) to maximize launch and reduce spin. prescriptive drills and progression criteria include:

- Impact-bag drill – rehearse compressing the bag to feel forward shaft lean and square face at impact; progress when >80% of strikes register center-face on impact tape.

- Low-point gate – set two tees to force the club to bottom out in front of the ball for irons; progress by narrowing the gate as consistency improves.

- Tee/ground alternation – alternate driver off a tee and 7-iron off the turf to develop appropriate attack angles for different clubs.

Address common faults with targeted fixes (casting corrected with impact-bag and lag drills; early extension corrected with chair drill and core-strengthening routines), and incorporate mental strategies – pre-shot routines, targeted visualization of tempo, and in-round tempo cues – to transfer practice gains to competition. Set measurable on-course goals (for example, achieve 80% fairways or greens in regulation on a practice nine or reduce three-putt frequency by a given percent) and adapt equipment choices (shaft flex, loft, ball compression) only after confirming technique consistency, not before. This integrated progression ensures tempo, axis control, and ball contact improvements translate into lower scores and more reliable course management.

Integrating Strength, Mobility, and Load Management: Recommended Screening Tests and Conditioning Protocols to reduce Injury Risk

begin with a systematic movement and strength screen to establish objective baselines that directly inform swing technique and injury prevention. Recommended assessments include the Y-Balance Test (look for anterior reach asymmetry <4 cm), a single-leg balance test with eyes open (target: 30+ seconds), and a seated or standing thoracic rotation test (target: ≥45° each side). in addition, perform hip internal/external rotation measurements with a goniometer-hip IR <30° often correlates with compensatory lumbar rotation and early extension in the downswing-and a Thomas test to detect hip flexor tightness that can alter pelvis tilt at address. For the shoulders and rotator cuff, use resisted external rotation endurance (timed holds at 0°-20° of abduction) to assess capacity for repetitive backswing/throwing loads; deficits here increase risk of lateral elbow or shoulder pain during long practice sessions. include a dynamic movement screen such as a loaded overhead squat or a closed-chain plank to single-arm reach to evaluate scapular stability and core endurance, both critical for maintaining spine angle through impact. Together, these measures should be recorded numerically and re-tested every 6-8 weeks so instructors can link specific limitations to swing faults-e.g., limited thoracic rotation corresponds to a shortened backswing and compensated hip slide-and prioritize targeted interventions.

Following screening, prescribe an integrated conditioning protocol that progresses from mobility to strength to power, and ties directly to golf-specific mechanics. begin with daily mobility routines emphasizing thoracic rotation (3 sets × 8-10 controlled reps per side), hip internal rotation and posterior hip capsule work (2-3 × 30 seconds holds per drill), and ankle dorsiflexion mobility (2 × 10 deep squat hold). Then implement strength sessions 2-3×/week with clear parameters: 3 sets of 8-12 reps for compound lifts (Romanian deadlifts, split squats, and single-leg deadlifts) to build glute and posterior-chain strength that stabilizes the pelvis in transition. Progress to power work 1-2×/week-medicine ball rotational throws or banded woodchops at 3-5 sets of 5-8 explosive reps-to transfer strength into clubhead speed and improved angular velocity through impact.For swing-specific motor learning, integrate tempo and control drills: a slow-motion takeaway (counted 3 seconds) followed by a controlled transition (1 second) and full acceleration through impact helps ingrain correct sequencing and reduces compensatory rapid rotations. Use the following practical drills and checkpoints to guide practice and troubleshooting:

- Medicine ball rotational throws: 3-5 sets × 6 reps each side-focus on hip-first sequencing.

- banded external rotation: 3 × 12 per side-to protect the lead shoulder and promote a safe takeaway.

- Single-leg RDL to balance target: 3 × 8-to address lateral sway and increase stability through the trailing leg.

- tempo swing drill (3-1-1): improves transition timing; reduce club length for beginners.

Equipment considerations also matter: use a slightly softer grip pressure, ensure shaft flex matches swing speed, and when using weighted clubs or overload/underload clubs keep sets low (10-20 swings total) and avoid heavy weighted swings if reporting back/shoulder pain. These protocols provide measurable goals-such as increasing thoracic rotation by 10° in 8 weeks or improving single-leg balance time by 15 seconds-and are adaptable for beginners (lower load, higher emphasis on mobility and motor control) through low-handicap players (higher-load strength and targeted power sessions).

apply explicit load-management rules so physical conditioning translates safely into improved scoring and course strategy. Monitor practice and play volume with an evidence-based progression: start with a conservative baseline (e.g., 30-60 full swings per range session for beginners, 60-120 for advanced players) and increase total swings or training load by no more than ~10% per week to minimize overuse injury risk; allow at least 48 hours recovery between high-intensity strength or power sessions for the same muscle groups. On course, teach situational adjustments that reduce biomechanical stress without sacrificing strategy-when fatigued or when greens are firm, shorten the swing to a controlled three-quarter turn, favor a lower-lofted club to limit excessive wrist hinge, or elect a 3-wood off the tee on narrow fairways to reduce torque on the lumbar spine and shoulders. Include a monitoring routine: daily pain or soreness diary, rate of perceived exertion (RPE) for sessions, and weekly subjective readiness scores; if persistent soreness >48-72 hours occurs, reduce swing volume and prioritize mobility and low-load stability work. Cognitive strategies such as a consistent pre-shot breathing routine and focusing on process goals (body positions and sequencing) will mitigate tension-related compensations that often precipitate injury. By linking objective screening results, targeted conditioning, and disciplined load management to course decisions-like playing for position instead of maximum distance-golfers at every level can protect tissue, refine technique, and ultimately lower scores in a enduring, measurable way.

Leveraging Technology and Objective KPIs to Measure Progress: Using Trackers,Video Analysis,and Statistical Thresholds for Consistency

Begin by establishing an objective baseline with modern measurement tools: a launch monitor (radar/photometric),a clubhead- and swing-tracking wearable,and high-frame-rate video. Collect data in a controlled protocol-after a standardized warm-up, hit 10-20 shots per club using the same ball model and turf condition, and record median values for each metric to reduce outliers. Track key performance indicators (KPIs) that directly link to scoring: clubhead speed (mph), ball speed, launch angle (degrees), spin rate (rpm), carry distance (yards), lateral dispersion (yards), GIR% (greens in regulation), scrambling%, and strokes gained components (tee-to-green, approach, short game, putting).Set tiered, time-bound targets-e.g., for a mid-handicap player aim to increase driver clubhead speed by 3-5 mph over 8-12 weeks, achieve driver launch between 10°-14° with spin 1,800-2,800 rpm (depending on loft), and reduce lateral 95% dispersion to within 15 yards. In addition, use statistical thresholds to trigger tactical changes on the course: if approach dispersion exceeds 12-15 yards with a given club, favor a conservative club selection to avoid short-side bunkers and to improve scoring consistency.

Complement numerical data with systematic video biomechanics to diagnose and correct technical faults.Capture at least two synchronized views (face-on and down-the-line) at 120-240 fps for slow-motion analysis; measure and annotate spine tilt at address and impact, shoulder turn (aim ~90° for advanced, ~70°-90° for most adults), hip rotation (target ~40°-50° for amateurs), swing plane angle, and shaft lean at impact (typically 5°-10° forward for short irons). Then apply targeted drills and checkpoints to translate the video findings into feel and repeatability:

- Setup checkpoints: ball position relative to lead heel, weight distribution ~55/45% (lead/trail) at address for full shots, and neutral grip pressure (pressure scale ~4-5/10).

- Practice drills: impact bag or towel drill to promote shaft lean, low-to-high driver tee drill to encourage positive attack angle (+1° to +3°), and pause-at-top drill to improve transition sequencing.

- Troubleshooting steps: if casting occurs, shorten the takeaway and focus on maintaining wrist hinge; if early extension appears, strengthen posture with a wall-tap or hip-bump drill to preserve spine angle through impact.

For each drill assign measurable benchmarks (for example, reduce early extension by 10°-15° on video within six weeks or improve average smash factor by 0.03) and adapt cues to learning style: use tactile implements for kinesthetic learners, annotated slow-motion clips for visual learners, and concise verbal cues for auditory learners.

integrate the objective KPIs and video-informed mechanics into course strategy and practice design to produce measurable scoring gains. Translate practice metrics into on-course decisions: when your monitor shows an average 7-iron carry of 150 yards ± 8 yards, plan layups and club choices around the lower bound of that window when facing hazards or firm greens; conversely, when dispersion and launch data indicate reliable spin control inside 100 yards, attack pins aggressively. Use statistical thresholds to manage risk-e.g., if putting strokes gained is below 0 over a 4-round sample, allocate 40-50% of short-game practice to distance control and proximity-to-hole drills (20, 40, 60 feet). Simulate on-course conditions in practice by varying lie, wind, and green speed, and adopt pre-shot routines that reference KPIs (“confirm target carry, confirm dispersion window, commit”) to reduce indecision under pressure. Across all skill levels, prioritize process goals (consistent setup, repeatable impact) over outcome-only goals; as a notable example, a beginner’s goal might potentially be to achieve consistent ball position and posture 80% of the time, while a low handicapper may aim to keep driver 95% dispersion within 12 yards and show a net +0.2 strokes gained approach over baseline-all measured and tracked weekly to ensure progressive, evidence-based improvement.

Q&A

Note regarding provided search results: the search results supplied with the request do not pertain to golf biomechanics or coaching; they appear to reference unrelated topics (graduate study and consumer electronics). the Q&A below is thus compiled from accepted biomechanical principles and applied coaching practice rather than those search items.

Q1 – What is the evidence-based purpose of the article “Master Your Golf Swing: Evidence-Based Techniques for Every Skill Level”?

Answer: The article synthesizes peer-reviewed biomechanical findings and applied coaching literature to identify the mechanical and motor-control determinants of an effective golf swing, translate those determinants into practical assessment metrics, and prescribe drills and training progressions that are appropriate for beginners, developing players, and advanced golfers. Its goal is to enable measurable performance improvement (clubhead speed, ball speed, accuracy, repeatability) while minimizing injury risk.

Q2 – what are the primary biomechanical principles that underpin an efficient and repeatable golf swing?

Answer: Key principles include:

– Proper sequencing of body segments (proximal-to-distal kinematic sequence): pelvis initiates rotation, followed by thorax, then arms and club, producing efficient energy transfer to the clubhead.

– Generation and transfer of ground reaction forces into rotational power (vertical and horizontal force application).

– Maintenance of a stable but mobile base (optimal center of mass control and postural support).

– Appropriate separation between pelvis and thorax (commonly described as “X‑factor”) to store elastic energy.- Temporal consistency (tempo and rhythm) and an impact-position that optimizes clubface orientation,speed,and attack angle.

Q3 – How does the kinematic sequence influence clubhead speed and shot consistency?

Answer: Empirical studies indicate that an ordered kinematic sequence (pelvis → thorax → arms → club) maximizes angular velocity transfer and clubhead speed while reducing compensatory motions. Deviations (e.g., early arm firing or “casting”) reduce efficiency, increase variability in clubface orientation at impact, and thus decrease ball speed and accuracy.

Q4 – What common swing faults can be explained by biomechanics, and what are their effects?

answer: Examples:

– Casting/early release: premature wrist uncocking reduces lever length and clubhead speed.- Over-rotation or sway of the lower body: disrupts sequencing and balance, leading to inconsistent strike location.- Reverse pivot: poor weight transfer reduces ground reaction force contribution and changes attack angle.- Excessive lateral head movement: alters spine angle and impacts strike plane consistency.

Each fault alters the energy pathway, timing, or impact geometry, producing measurable changes in ball flight and dispersion.

Q5 – Which objective metrics should coaches and players use to assess swing performance?

Answer: essential measurable metrics include:

– Clubhead speed, ball speed, smash factor (ball speed/clubhead speed).

– Launch angle and spin rate.

– Carry distance and dispersion (lateral and longitudinal).

– Attack angle and club path.

– Kinematic metrics where available: pelvis and thorax angular velocities and separation, timing of peak segmental velocities.

– Ground reaction forces or weight-shift profiles (when force plates or pressure mats are available).

– Temporal metrics: backswing duration, downswing duration, and overall tempo ratio.

Q6 – How should assessments be adapted by skill level?

Answer:

- Beginners: prioritize basic movement screens (T‑spine rotation, hip mobility, single-leg balance), simple swing rhythm, and measurable clubhead speed and contact quality (smash factor).

– Intermediate: add launch-monitor metrics (launch angle, spin, dispersion), video analysis for sequencing, and basic strength/mobility testing.

- Advanced: incorporate kinetic and kinematic measures (force plates, IMUs), detailed impact-position analysis, and sport-specific strength/power testing.

Q7 – What are evidence-based drills to improve sequencing and power?

Answer: Effective drills (with rationale):

– Towel or headcover under lead arm drill: promotes synchronized body rotation and reduces casting by maintaining arm-body connection.

– Step drill (step toward target at transition): ingrains ground-force shift and proper weight transfer.

– Medicine‑ball rotational throws (short, explosive): develop proximal-to-distal power and train dynamic trunk rotation.

– Impact‑bag or rail drill: emphasizes correct impact posture and reinforces forward shaft lean/centered strike.

– Slow‑motion to full‑speed progression with video feedback: improves timing and motor learning through explicit external focus cues.

Q8 – What mobility and strength assessments and interventions are recommended?

Answer: Assessments: thoracic rotation (seated or standing), hip internal/external rotation, single-leg balance and squat patterning, ankle dorsiflexion, and core stability tests (timed plank, anti-rotation). Interventions: thoracic-mobility drills, hip-mobility and glute-activation exercises, posterior-chain strengthening (hip hinge variations), anti-rotation core work (Pallof press), and rotational power training (medicine-ball chops/throws). The interventions should be individualized based on deficits uncovered by screening.

Q9 – How should practice be structured (progression and periodization) for skill development?

Answer: Principles:

- Progressive overload in motor complexity and speed: begin with technical drills at low speed, progress to speed-focused drills, then to on-course simulation.

– Use a mix of blocked (skill acquisition) and random (skill retention and transfer) practice; emphasize random practice as skill consolidates.

– Deliberate practice with immediate, specific feedback (video, launch monitor) and defined goals.

– Micro-periodization: alternate technique-focused sessions with power/speed sessions and recovery/recovery mobility.

– Long-term periodization: off-season emphasis on physical development; pre-season on speed and transition to skill integration; in-season maintenance.

Q10 – What technologies are useful and how should they be used appropriately?

Answer: Useful tools: high-speed video for kinematic observation, launch monitors for ball‑flight and impact metrics, IMUs for segmental timing, and force plates or pressure mats for ground reaction analysis.Use them to quantify baseline, track objective change, and provide immediate, actionable feedback. Avoid over-reliance on technology at the expense of basic movement quality; prioritize measures with demonstrated reliability and interpret them within the context of the player’s goals.

Q11 – How should coaches measure and interpret improvement?

Answer: Implement pre/post testing for key metrics (clubhead speed, smash factor, carry distance, dispersion), ensure tests are reliable and standardized (same clubs, ball type, environmental control). Use smallest detectable change or minimal clinically significant difference frameworks where available to determine meaningful improvement. Combine objective measures with qualitative indicators (shot outcomes,on-course performance).

Q12 – What injury-prevention considerations arise from the biomechanics of the swing?

Answer: Common injury risks include low-back strain (from excessive shear or poor trunk sequencing), wrist and elbow overload (from poor impact mechanics), and hip/groin injuries (from inadequate mobility or abrupt force transfer). Mitigation strategies: correct movement faults (reduce excessive lumbar extension/rotation), improve core and hip control, ensure progressive loading, and monitor training volume and recovery.

Q13 – What coaching cues and attentional focus are most effective?

Answer: Evidence favors external-focus cues (e.g., “accelerate the clubhead through the ball” or “rotate the chest toward the target”) over internal-focus cues for promoting automaticity and performance under pressure. Use concise, action-oriented cues tailored to the player’s level and coordinate them with demonstrations and feedback.

Q14 - How can a coach individualize instruction given inter-individual variability?

Answer: Individualize by:

– Conducting a extensive movement and performance assessment.

- Identifying physiological constraints (mobility or strength deficits), technical faults, and the player’s learning preferences.

– Prioritizing interventions that address the limiting factor for performance (e.g., mobility vs. sequencing vs. power).

– setting measurable, time-bound goals and iteratively adjusting based on objective progress.

Q15 – What common misconceptions should be dispelled?

Answer:

– “There is one perfect swing.” Evidence supports multiple triumphant movement solutions; the objective is efficiency,repeatability,and fit with the athlete’s morphology and abilities.- “More force always means better results.” Force must be effectively sequenced and directed; high force with poor timing increases variability and injury risk.- “Technology replaces coaching.” Technology augments diagnostic and feedback capacity but does not replace the coach’s role in interpretation and individualized programming.

Q16 – How can players and coaches translate these principles into a weekly practice plan?

Answer: Example weekly framework (modifiable by level):

- 2 technique sessions (30-45 minutes) focusing on prescribed drills with video feedback.

– 2 power/speed sessions (short, high-intensity medicine‑ball or rotational cable work) with adequate recovery.

– 1 long-session integrating full-swing practice and course management under variable conditions.

– Daily short mobility/activation routines (10-15 minutes).

– Include one evaluation session every 4-8 weeks using the agreed metrics.

Q17 – What are realistic timelines for observable improvements?

Answer: Timelines depend on starting level and focus:

– Beginners may show measurable ball-striking improvements (contact quality, basic dispersion) within weeks.

- Technical changes affecting sequencing and power often require 6-12 weeks of consistent, focused practice.

– Physiological adaptations (strength, mobility) typically require 8-16 weeks to produce meaningful changes in swing mechanics and performance.

Q18 – Where should readers look for primary scientific literature to deepen understanding?

Answer: Seek peer-reviewed journals in sports biomechanics, motor control, and applied sports science. Key topics to search: kinematic sequencing in golf, ground reaction forces in rotational sports, motor learning in skilled performance, and sport-specific strength and conditioning for golf.

Closing note: The recommendations above combine biomechanical principles, motor-learning evidence, and applied coaching practice. For maximal benefit, pair objective assessment (launch monitor, video) with a movement-screening protocol and individualized training plans that address both technical and physical constraints.

In closing, the evidence reviewed in this article reinforces that mastery of the golf swing is achieved not by allegiance to a single stylistic ideal but through systematic, evidence-based practice that integrates biomechanical insight, motor-learning principles, and objective measurement. Coaches and players who prioritize individualized assessment, progressive overload of task demands, and high-quality, variable feedback-supported by tools such as biomechanical analysis, video feedback, and launch-monitor metrics-can accelerate skill acquisition and transfer under competitive conditions.

For practitioners, this means designing level-specific training plans that balance technique refinement with outcome-focused drills and deliberate practice; for researchers, it highlights opportunities to evaluate long-term retention, error-tolerance strategies, and the interaction of physical and cognitive constraints on swing variability.Ultimately, adopting a rigorous, data-driven approach will improve consistency, increase driving and iron performance, and provide a clearer pathway for players at every skill level to master the golf swing.