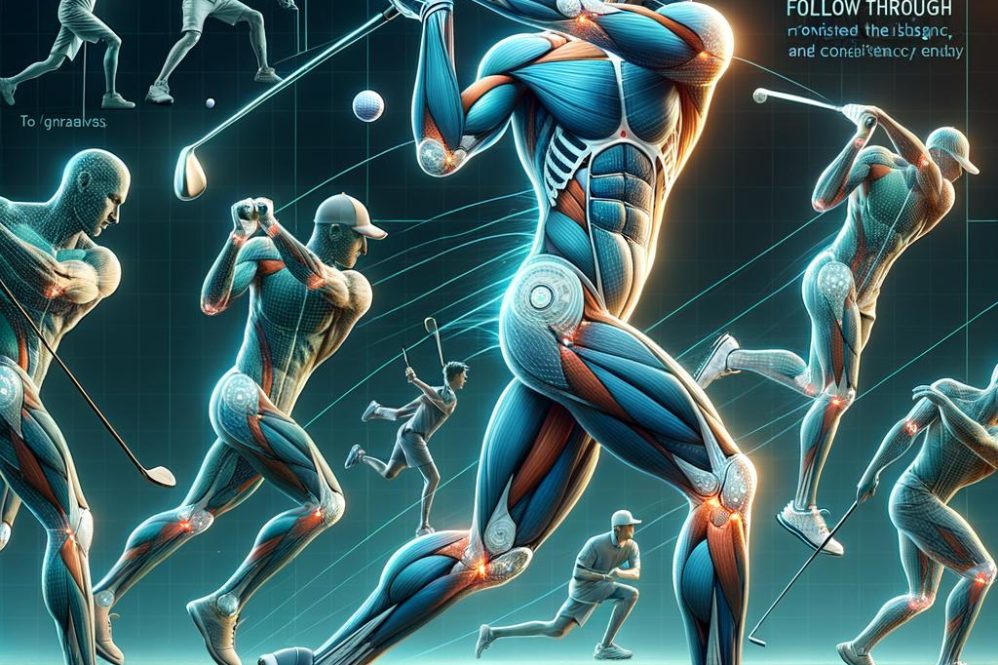

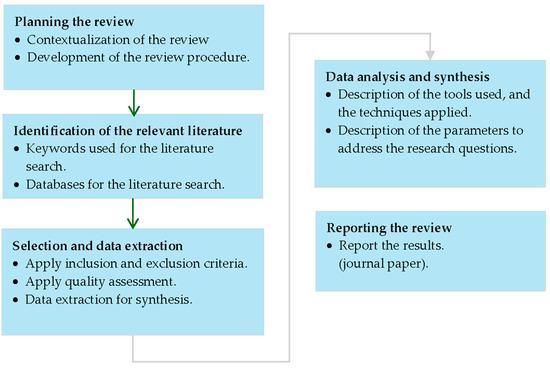

Effective execution of the follow-through is a primary driver of shot accuracy, distance management, and long‑term joint health in golf. The finish of the swing is a visible summary of the swing’s kinematic sequencing, energy flow, and neuromuscular control established in the backswing and downswing; imperfections in the follow‑through often point back to problems earlier in the movement chain.from a mechanical standpoint, a stable lower body, coordinated trunk rotation, managed deceleration of distal segments, and a consistent clubface at impact jointly determine ball trajectory and lateral dispersion. Recent field work using wearable sensors and launch monitors reinforces that follow‑through mechanics are not merely stylistic- they are measurable outcomes that relate directly to performance and injury risk.

This article condenses current biomechanical thinking to highlight the main mechanical drivers of an effective follow‑through, examines links to performance and injury, and converts those insights into practical, evidence‑informed coaching methods and drills. By blending quantitative markers with usable instruction, the aim is to give coaches and players reproducible tools to tighten shot dispersion, improve energy transfer, and lower cumulative load across ability levels.

Biomechanical principles behind the golf follow‑through: sequencing and transfer of loads

Efficient swing mechanics rely on a reliable proximal‑to‑distal activation sequence: the legs contact the ground to produce ground reaction forces that are relayed through the pelvis, then the thorax, into the shoulder complex and finally the hands and club. When this timing is preserved, angular velocity rises progressively from hip → shoulder → wrist and peak clubhead speed typically follows peak thoracic rotation. This order capitalizes on multi‑joint stretch‑shortening benefits and helps avoid simultaneous opposing torques that waste kinetic energy.

Transfer of momentum depends on coordinated segment rotations and a purposeful weight shift. The period instantly after impact must allow residual kinetic energy to be absorbed in a controlled way while keeping the ball on the intended line. The principal mechanical elements are:

- Ground reaction forces – provide the impulse that initiates rotational torque.

- Pelvic rotation – times the hand‑off of angular momentum into the torso.

- Thoracic rotation and shoulder sequencing – guide the shaft path and enable wrist lag and release.

- Distal deceleration – eccentric activity in the forearm and rotator cuff that limits excessive post‑impact loads.

Decelerative control is as crucial as acceleration for both outcomes and injury prevention. Eccentric capacity in the lead shoulder and forearm dampens leftover club momentum; inadequate eccentric strength or mistimed segment sequencing raises valgus and shear stresses on the elbow and shoulder. For applied coaching and measurement, focus on repeatable kinematic and load markers such as relative timing of pelvic and thoracic peak angular velocities, the direction and magnitude of ground reaction forces, and the eccentric braking torque at the lead shoulder.Tools like high‑speed video, force plates, and IMUs can quantify these targets and shape interventions that improve sequencing and load transfer, reducing dispersion and joint wear over time.

Building a stable base: lower‑body strategies for a reliable follow‑through

A consistent finish begins with the feet, knees, hips and trunk working together; the forces generated through the legs form the foundation the upper body uses to move the club. An effective pattern features a braced lead leg that accepts lateral and vertical load while the pelvis continues to rotate. A stable but supple base-slight knee flexion with a bit of dorsiflexion at the lead ankle around impact-permits controlled deceleration of the club and prevents unneeded upper‑body tension. In short, learn to absorb and redirect force through the hips instead of trying to stop motion with the hands.

Practical adjustments to optimize that force pathway include purposeful foot setup, staged weight transfer, and timed hip clearance. Useful components are:

- Varying stance width to find lateral stability for different club lengths and shot types.

- Lead‑leg bracing drills to train eccentric quadriceps and gluteal control.

- Pelvis‑frist sequencing drills (for example, step‑through repetitions) that reinforce initiating rotation from the hips.

- Ground‑awareness exercises using textured mats or pressure feedback to heighten connection to the turf.

From a conditioning standpoint, lower‑body resilience and proprioception are key to repeating good follow‑through mechanics. Strength work should prioritize unilateral hip and knee function (single‑leg Romanian deadlifts, Bulgarian split squats), rotational power development (medicine‑ball chest and side throws), and eccentric control (slow single‑leg descents). Mobility targets typically include thoracic rotation and ankle dorsiflexion so the hips can turn fully and the weight can move forward without balance loss. Regular neuromuscular training-balance holds, reactive perturbations, and tempo‑controlled swings-helps preserve technique under pressure or in irregular lies.

Quick, objective cues speed learning. Track simple on‑range metrics-weight distribution at impact, peak pelvic rotation, and center‑of‑pressure travel-to judge progress.The table below condenses practical targets and coaching prompts you can use during practice.

| Metric | target | Coaching Cue |

|---|---|---|

| Lead‑leg force share at impact | Approximately 60-70% | “Press the lead foot down-stay tall, don’t fold.” |

| Pelvic rotation through follow‑through | Roughly 45°-60° from address | “Turn the hips well beyond the ball.” |

| COP lateral shift | Clear heel‑to‑toe progression | “Feel the weight roll to the lead side.” |

Upper‑body sequencing and keeping the clubface true through the finish

Maintaining clubface alignment through the follow‑through depends on coordinated upper‑body motion and finely timed distal rotations. High thoracic rotation velocity right after impact helps stabilize the rotational axis around which shaft and hosel rotate, supporting face control. Simultaneously, measured scapular movement and controlled external rotation at the shoulder reduce unwanted wrist torques; when proximal segments decelerate smoothly, the impulse that reaches the forearm and clubhead is moderated and face‑angle bias is minimized. Mechanically, a good finish shows gradual reductions in angular velocity down the chain (trunk → upper arm → forearm) so that the clubhead passes through the release window with a neutral orientation.

Primary kinematic contributors to face control include:

- Timing between trunk and pelvis – dependable proximal sequencing creates a stable reference for the shoulders.

- Scapulothoracic motion – controlled protraction and retraction help prevent compensatory wrist actions.

- Elbow extension timing – a late, progressive extension smooths shaft plane changes.

- Forearm rotation - precise pronation/supination immediately after impact fine‑tunes face angle.

These factors interact in complex ways; a small shortfall in one area (for example, delayed trunk deceleration) can magnify distal deviations and produce measurable face misalignments at release. Objective measures such as thoracic angular velocity, peak scapular protraction, and forearm pronation rates-obtainable with IMUs or high‑speed cameras-help identify which elements to prioritize in training.

| Kinematic Variable | Desired Pattern | Effect on Clubface |

|---|---|---|

| Thoracic angular velocity | High peak,then smooth decay | Keeps rotation axis steady; reduces face twist |

| Scapular protraction | Measured and controlled | Limits compensatory wrist roll |

| Forearm pronation rate | Moderate and well timed | Aligns face through the release window |

Train the timing and sensory awareness of proximal deceleration with targeted drills. Useful examples are reduced‑backswing impact‑to‑finish repetitions to isolate trunk timing and resistance‑band patterns that encourage smooth scapular motion during extension. Evidence from applied interventions suggests that reducing abrupt angular impulses at the shoulder and encouraging graded forearm rotation produces the most consistent gains in face stability while preserving clubhead speed.

Timing and rhythm: drills to align phases and stabilize the finish

Repeatable follow‑throughs stem from reliable temporal sequencing: hips initiate, the thorax follows, and the hands release to complete the chain. The commonly used benchmark of about a 3:1 backswing‑to‑downswing tempo is a useful starting point,but it must be individualized. Consistency improves when intersegmental onset times (pelvis → thorax → forearms) are reproducible and when neuromuscular activation timing is preserved across repetitions. Focus on kinematic sequencing, intersegment timing, and conserving angular momentum through impact to reduce mid‑flight variability.

Progressively structured drills that first isolate timing and then recombine elements are most effective. Try:

- Metronome tempo drill – practice to an audible cadence that enforces a 3:1 ratio; begin slowly and add speed as timing stabilizes.

- Pause‑at‑top drill – hold the transition 0.5-1.0 s to sharpen initiation from the lower body.

- Step‑and‑swing – a half‑step toward the target on the downswing to ingrain timely weight shift between pelvis and thorax.

- Progressive acceleration - sets of 5 slow, 5 medium and 5 full swings emphasizing smooth build and a controlled finish.

- Mirror/impact‑bag finish drill – use visual or tactile feedback to reinforce a balanced, active finish with the club high and stable.

Augment drills with sensory feedback and objective checkpoints: metronome or tempo apps for auditory entrainment, slow‑motion video for kinematic review, and light pressure‑sensing mats to verify timely weight transfer. Coaches should move players from constrained, low‑variability practice toward high‑variability, context‑rich sets to improve retention and adaptability of timing under real conditions.

| Drill | Primary Target | Tempo Cue |

|---|---|---|

| Metronome Tempo | Overall cadence | “Three beats back, one beat down” |

| Pause‑at‑Top | Transition timing | “Hold 0.7 s, then let the hips go” |

| Step‑and‑Swing | Weight transfer | “Step, rotate, release” |

Measure improvements with pre/post testing: track shot dispersion, the percentage of swings within a metronome window (for example ±0.1 s), and the video timing of pelvis vs thorax initiation. A practical weekly template is 3-4 sessions with 4-6 drill‑focused sets of 8-12 reps, supplemented by occasional high‑variability practice rounds to ensure transfer. Watch for neuromuscular fatigue-timing breakdowns often precede larger mechanical failures-and include recovery and consolidation periods. Regular, tempo‑controlled repetition yields quantifiable increases in follow‑through stability and shot reproducibility.

Typical follow‑through faults and corrective, evidence‑based exercises

Common technical failures typically present as predictable follow‑through deviations: premature release (loss of lag), lateral sway or reverse pivot, a collapsed lead wrist, or an abbreviated torso and hip rotation. These breakdowns shrink effective swing radius, misalign the clubface at impact, and reduce efficient energy transfer from the legs and hips to the hands. Often they coincide with overuse of forearm flexors and under‑recruitment of the gluteal complex, increasing dispersion and reducing resilience under pressure.

Targeted corrective approaches focus on restoring mobility, retraining sequencing, and improving force transfer. Strongly supported or theoretically sound drills include:

- Medicine‑ball rotational throws (3-4 sets of 6-8 reps) to rehearse trunk‑to‑arm energy transfer and improve sequencing for rotational power.

- Single‑leg deadlifts with an emphasis on hip‑hinge control (2-3 sets of 8-10 reps) to stabilize the lower limb and reduce lateral sway.

- Thoracic mobility work (open‑book variations and foam‑roller routines) performed regularly to enable fuller upper‑torso rotation through impact.

- Impact bag and pause‑at‑impact drills to reinforce correct wrist angles and discourage early release by increasing proprioceptive feedback.

The matrix below links common faults to probable causes and practical drills to speed transfer from the range to the course:

| Observed Fault | Probable Cause | Corrective Drill |

|---|---|---|

| Early release | Forearm dominance; weak sequencing | Impact bag + pause‑at‑impact |

| Reverse pivot / sway | Poor single‑leg stability; weak gluteals | Single‑leg RDL + step‑through swings |

| Limited rotation | Restricted thoracic mobility | Thoracic mobility drills + med‑ball throws |

Progressions and cueing should follow a logical sequence: start with mobility and activation, move to low‑speed sequencing patterns, then reintroduce variable‑speed ball work. track objective markers (pelvic rotation degrees, dispersion, clubhead speed) and subjective feedback (feel of lag, balance on the finish). Use concise cues such as “lead hip clear, chest rotate, keep the wrist triangle” and support practice with augmented feedback (video, impact bag, radar) to speed motor learning. A typical corrective rhythm is 3-4 brief sessions per week with reassessments every 4-6 weeks to document kinematic change and update the program.

Blending mobility and strength work to protect and reinforce follow‑through mechanics

A strong follow‑through is the product of coordinated joint mobility, segmental strength, and sensorimotor control-not the output of any single muscle group. Mobility and strength must be integrated so range,stiffness and force production work together to support repeatable movement.Mobility secures end‑range positions needed for a full finish (thoracic rotation, hip external rotation, ankle dorsiflexion), while progressive strength and stiffness in the hips, core and lead arm provide the eccentric braking and efficient transfer necesary for controlled deceleration.

A practical training framework targets tissue capacity and neural control concurrently. Core elements include:

- Mobility work – thoracic rotations, lead‑hip openers and ankle drills to maintain full swing geometry.

- Stability development – anti‑rotation and anti‑extension exercises to preserve trunk dissociation and protect the lumbar spine during high rotational speeds.

- Loaded strength – posterior chain and unilateral lower‑limb lifts (Romanian deadlifts, split squats) to build a robust torque platform.

- Reactive power – medicine‑ball throws and plyometric deceleration drills to teach rapid eccentric control relevant to follow‑through braking.

| Microcycle Session | Primary Focus | Representative Drill |

|---|---|---|

| Session A | End‑range mobility & movement patterns | Thoracic windmills + banded lead‑hip opener |

| Session B | Strength & eccentric control | single‑leg RDL + slow eccentric rows |

| Session C | Power & integration | rotational med‑ball throws + controlled finish holds |

Objective monitoring and progressive overload make adaptations transferable to on‑course situations. Track kinematic proxies (pelvis‑thorax separation, follow‑through arm extension), physiological measures (single‑leg balance time, eccentric strength ratios), and performance outcomes (post‑impact deceleration profiles, dispersion under fatigue). Practical testing tools include high‑speed swing video, force‑plate balance checks and handheld dynamometry. Emphasize specificity, gradual overload, and staged motor learning: start slow with controlled ranges, progress to loaded strength, and finish with high‑velocity integration so the follow‑through becomes both repeatable and resilient under pressure.

Monitoring progress: objective metrics and practice plans for lasting gains

Meaningful progress begins with reliable baselines across kinematic, kinetic and ball‑flight measures-examples include peak clubhead speed, face angle at impact, swing‑path deviation, pelvis‑to‑shoulder separation, and finish stability (time held on the lead leg). use validated measurement tools (launch monitors, high‑speed video, IMUs, force plates) and collect enough trials-commonly 30 swings-to estimate central tendency and variability. Record means and standard deviations so changes can be judged statistically and practically rather than by feeling alone.

Convert metrics into structured practice protocols that prioritize transfer to the course. Useful templates are:

- Baseline testing – 30 swings in consistent conditions (same club,surface,ball) with launch monitor and video.

- Deliberate repetition – 5 sets of 10 swings focused on one metric (for example finish hold), with immediate feedback from video or an IMU.

- Randomized transfer – mixed‑club sequences of 15-20 shots to build adaptability after blocked mastery.

- Fatigue‑controlled sessions – cap quality swings at around 120 per session; end or modify work when objective markers (clubhead speed drop, dispersion increase) indicate decline.

Pair each protocol with clear success criteria (for instance, reduce face‑angle variability by 20% or maintain a finish hold ≥1.5 s on 80% of reps) to decide when to advance training.

| Metric | Target Range (example) | Measurement Tool |

|---|---|---|

| Clubhead speed | Within ±3% of baseline | Launch monitor |

| Face angle at impact | Within ±2° | Launch monitor / video |

| Finish hold duration | ≥1.0-1.5 s | High‑speed camera / stopwatch |

| Lateral dispersion | Approximately ±8 yards | Launch monitor |

Interpreting data demands both statistical care and coaching context. Track moving averages and confidence intervals to separate real trends from session noise; a practical rule is to seek consistent improvement across three consecutive tests before increasing training complexity. Apply progressive overload-small increases in tempo, volume or variability-only when key metrics remain within target ranges. Schedule re‑tests every 2-4 weeks and maintain periodic retention sessions that prioritize variability and on‑course scenarios so measured gains in follow‑through mechanics carry over to performance.

Q&A

below is an academic‑style Q&A to accompany “Mastering Follow‑Through Mechanics for Golf Performance.” The set covers biomechanical principles, kinematics, muscle coordination, feedback strategies, assessment methods, training plans and research directions related to the follow‑through’s role in consistency and precision.Q1.What is the follow‑through in a golf swing,and why does it matter?

A1. The follow‑through is the phase after ball impact when the body and club continue to move until motion dissipates. It’s important because it reflects how well energy was transferred, how intact the kinematic sequence was, and how efficiently neuromuscular control was applied. A clean follow‑through commonly links with consistent face orientation at impact,predictable ball flight,lower risk of injury from abrupt decelerations,and reliable dispersion.

Q2. How does the follow‑through relate to the kinematic sequence?

A2. The follow‑through is the terminal expression of the proximal‑to‑distal kinematic sequence-pelvis then torso, then shoulders and arms, finishing with the hands and clubhead. A good finish implies momentum and rotational forces were produced and handed off properly; irregular finishes often indicate sequencing failures earlier (such as, early release or reverse pivot) that compromise impact mechanics.

Q3. Which kinematic follow‑through variables most strongly link to precision and consistency?

A3. Important variables include:

– Trunk rotation amplitude and angular velocity during and after impact.

– Hip rotation and symmetry of weight transfer entering the finish.

– Shoulder plane and relative timing of shoulder vs hip rotation.

– Wrist and forearm pronation/supination immediately post‑impact.

– Clubhead path and face angle through and after contact.

Applied work tends to associate consistent trunk velocity and a stable clubhead path through impact with lower lateral dispersion and more repeatable shots.

Q4. What muscle groups and coordination patterns drive an effective follow‑through?

A4. Key contributors are:

– Hip extensors and rotators (gluteus maximus/medius, deep rotators) for pelvic rotation and weight transfer.

– Core muscles (obliques, rectus abdominis, erector spinae, multifidus) for trunk support and torque transmission.- Scapular stabilizers and shoulder muscles (rotator cuff, deltoids, trapezius) for controlled arm motion and shaft path control.- Forearm and wrist musculature for face control and release timing.

Coordination requires timed activation-hips and trunk generate torque, the core manages transfer, and distal muscles moderate release and braking.Q5. How do feedback mechanisms affect learning and executing the follow‑through?

A5. Intrinsic sensory feedback (proprioception, vision, vestibular input) guides in‑the‑moment adjustments. augmented feedback (video, launch monitors, coach cues, auditory signals) accelerates learning by making errors clearer. Best practice mixes intrinsic practice with intermittent augmented feedback to prevent overreliance and foster self‑monitoring.Q6. What objective tools are useful for assessing follow‑through biomechanics?

A6. Recommended instruments include:

– 3D motion capture for detailed kinematics.

– IMUs for field‑based rotation and displacement metrics.

– Force plates for ground reaction force profiles and weight transfer.

– EMG for muscle activation timing and magnitude.

– Launch monitors for ball and club metrics (ball speed, clubhead speed, face angle, path).

Combining modalities gives a fuller picture of kinetic, kinematic and neuromuscular behavior.

Q7. What common technical faults in the follow‑through reduce precision, and why do they happen?

A7. Common faults:

– Early deceleration of the follow‑through: often from poor proximal‑to‑distal sequencing or insufficient trunk rotation.

– Over‑rotation or balance loss: can stem from excessive lateral sway or late hip rotation.

– Collapsed lead arm or inconsistent release: usually caused by poor wrist/forearm timing or grip issues.

– Open or closed face at finish: frequently linked to inconsistent wrist timing or shoulder plane errors.

Diagnosis should focus on timing and sequencing rather than static finish positions alone.

Q8. Which coaching cues and drills best promote an effective follow‑through?

A8. Effective cues: “rotate through the ball,” ”finish tall,” “let the hips lead,” and “feel the release”-short, externally oriented prompts work well. Useful drills include towel‑under‑arms (promotes connection), step‑through swings (encourages weight transfer), medicine‑ball rotational throws (build sequencing and power), slow swings emphasizing smooth deceleration, and finish‑hold targets to reinforce balance. Progress from slow and blocked practice toward higher speed and randomized sets for better transfer.

Q9. How should follow‑through work be integrated into a periodized plan for competitive players?

A9.Integration stages:

– Foundation: mobility, strength and motor patterning with slow, focused reps.

– Skill acquisition: add augmented feedback, sequencing drills and speed progressions.

– Specificity: transfer into on‑course scenarios and speed‑accuracy tasks.

– Peaking: reduce volume, maintain feel and focus on consistency with few technical changes.

Use regular kinematic monitoring and dispersion metrics to inform adjustments across phases.

Q10. What effect do physical attributes (mobility, strength, power, endurance) have on the follow‑through?

A10. Physical qualities determine capacity to create and control rotation:

– Mobility enables full range (thoracic rotation, hip rotation, ankle dorsiflexion).

– Strength supports torque production and braking control.

– Power affects how quickly torque can be produced to achieve clubhead speed while maintaining sequence.

– Endurance preserves technique under fatigue; declines in endurance lead to degraded sequencing and increased dispersion.

A tailored conditioning plan addressing deficits improves follow‑through dependability.

Q11. How does fatigue change follow‑through mechanics and shot precision?

A11. Fatigue degrades neuromuscular coordination, slows reactions and reduces force output, often causing:

– Lower trunk rotation speed and range.

– Earlier or inconsistent release timing.

– Increased lateral sway and balance loss.

– Greater variability in path and face orientation.

These effects typically increase dispersion; training should include fatigue‑resilient skill work and conditioning to blunt decline.

Q12. What injuries are linked to poor follow‑through and how can they be reduced?

A12. injury risks include low‑back strain (from poor trunk control),shoulder impingement (from faulty deceleration),wrist tendonitis (from abrupt release),and knee/hip overload (from improper weight transfer). Mitigation strategies include technique correction, targeted strength and mobility programs (core, hips, thoracic spine), progressive loading with appropriate recovery, and workload monitoring.

Q13. How can a coach objectively determine whether follow‑through issues are causing inconsistent ball flight?

A13. A structured assessment should cover:

– Pre‑impact kinematics (pelvis/torso timing, ascent/descent patterns).

– Clubpath and face angle at impact via launch monitor or high‑speed video.

– Ground reaction force profile for weight transfer.

– Muscle timing via EMG if available.

- Correlation of kinematic and kinetic data with shot dispersion across repeated trials and varying conditions (fatigue, pressure) to establish causality.

Q14. Where are the evidence gaps and promising research directions in follow‑through biomechanics?

A14. Notable gaps:

– Longitudinal intervention trials focused specifically on follow‑through training and transfer to performance.

– Mechanistic studies linking follow‑through neuromuscular patterns to injury risk.

– Models that account for individual anthropometry to define personalized optimal finishes.

Future work should exploit wearables for large‑sample, ecologically valid datasets and integrate biomechanical with neurophysiological measures to better understand motor control adaptations.

Q15. Are individual differences important when prescribing follow‑through strategies?

A15. Absolutely. Anthropometry (limb lengths, torso‑to‑leg ratio), mobility, injury history and motor learning style mean optimal follow‑through strategies should be individualized. Functional assessments should guide tailored cueing, drill selection and conditioning while preserving basic sequencing and face‑control principles.Q16. How should technology (launch monitors, IMUs, video) be used without creating dependence?

A16. Best practices:

– Use tech for diagnosis and periodic benchmarking rather than constant feedback.

– Blend objective data with feel‑based drills to maintain intrinsic sensing.

– Adopt a faded feedback schedule-gradually reduce augmented feedback to foster autonomy.

- Keep data interpretation simple and actionable for the player.

Q17. Which practical metrics should coaches monitor to track follow‑through and precision gains?

A17. Track:

– Clubhead speed and its variability.

– Club path and face angle at impact and their standard deviations.

– Trunk and pelvis rotational velocities and timing offsets.

– Ball dispersion measures (carry SD, left/right spread).

– Finish balance metrics (COP, hold time).focus on trends and moving averages rather than single sessions.

Q18. Concise coaching takeaways for improving follow‑through to boost precision:

A18. Key points:

– Prioritize reliable proximal‑to‑distal sequencing: hips → torso → arms.- Strengthen balance and weight transfer so rotation into the finish is full and controlled.

– Use outcome‑focused cues and drills that reinforce smooth deceleration and consistent release.

– Address mobility and strength limitations that constrain the finish.

- Periodically use objective measures,but emphasize sensorimotor learning through varied practice and reduced external feedback.

Note on evidence and tools: While standard lab instruments deliver the highest precision, many coaches now rely on validated field tools (portable IMUs and modern launch monitors) to guide practical interventions. Contemporary coaching audits frequently report measurable reductions in dispersion and finish variability when objective feedback is combined with structured motor learning protocols.

A disciplined view of follow‑through mechanics-one that integrates sequencing, controlled deceleration, neuromuscular coordination and multimodal sensory feedback-creates a clear path to better accuracy and durability. The follow‑through is not an incidental flourish but a testable, trainable phase that both reflects and reinforces the quality of energy transfer produced earlier in the swing. For practitioners,this synthesis supports task‑specific drills emphasizing proximal‑to‑distal coordination,graded eccentric control of decelerators,and targeted sensory feedback (video cues,proprioceptive signals). Coaches should pair objective kinematic assessment with individualized neuromuscular profiling, and players should follow progressive motor‑learning plans that balance repetition with adaptive variability.

ongoing interdisciplinary research linking biomechanics, motor control and sensor technology will continue to sharpen evidence‑based interventions and measurement approaches that translate into on‑course gains. By treating the follow‑through as an intentional, measurable component of the swing, coaches and players can close the loop between technique, perception and performance.

Finish Strong: Mastering Follow-Through Mechanics for Better Golf Every Round

Refine your follow-through and you’ll see gains in distance,accuracy,and repeatability. Below are biomechanical principles, practical drills, common faults and fixes, and programmed practice routines designed to help golfers of all skill levels lock in a reliable finish and better ball striking.

Why the Follow-Through Matters (SEO keywords: follow-through, golf swing, ball striking)

The follow-through is more than a cosmetic finish – it’s the visible result of sequencing, balance, and energy transfer during the golf swing. A proper follow-through preserves clubhead speed, keeps the clubface stable through impact, and indicates efficient use of ground reaction forces and body rotation. In short:

- Follow-through = evidence of correct swing sequencing (proximal-to-distal power transfer).

- Consistent finish frequently enough correlates with consistent ball striking and shot direction.

- Controlled finish reduces compensations like scooping or flipping that cost distance and accuracy.

Key Biomechanical Principles (SEO keywords: biomechanics, ground reaction force, rotation)

1. Proximal-to-Distal Sequencing

Power is generated from larger, proximal segments (hips/torso) and transferred to distal segments (arms/hands/club). A proper follow-through indicates efficient energy transfer and timely release of the wrists.

2. Ground Reaction Forces (GRF) and Weight Transfer

Driving into the ground with the trailing leg and transferring weight to the front foot creates a ground-based push that amplifies clubhead speed. The follow-through should show the weight settled on the lead side with a stable base.

3. Rotation, Not slide

Efficient rotation of the pelvis and thorax around a relatively stable lower body prevents early extension and keeps the swing plane consistent. The finish shows upper body turned toward the target with the head balanced over or slightly behind the lead foot.

4. Deceleration control

The body decelerates after the ball is struck. A controlled deceleration (rather than abrupt stopping) keeps the club on plane longer and prevents flipping or scooping that reduces launch consistency.

Finish Positions That Tell a Story (SEO keywords: finish, stability, shot consistency)

- Balanced Finish: Weight on lead foot, chest and belt buckle facing the target, back foot on the toe – indicates stability and full rotation.

- Early Extension Finish: Hips thrust toward the ball and spine angle straightens – common cause of thin or fat strikes.

- Collapsed Finish: Hands fall and wrists break early – often follows loss of posture and reduced club speed.

Practical Cues to Improve Follow-Through (SEO keywords: swing cues, golf drills, tempo)

- “Finish on the target”: visualize holding the finish toward the target for two seconds after impact.

- “Lead hip clears, then stabilize”: Feel the trail hip rotate away and the lead hip clear without sliding forward.

- “Quiet head, rotating chest”: Keep the head stable while letting the torso rotate to the target.

- “Extend through impact”: Feel the arms extend along the shaft line after contact (not pulling in).

- “Smooth tempo”: Use an even backswing/downswing ratio (3:1 or 2:1) to remove jerky motions that ruin the finish.

Targeted Drills to Train a Championship Finish (SEO keywords: golf drills, follow-through drill)

Use these drills on the range or practice tee.Each drill targets a specific fault and creates grooveable movement patterns.

1. finish Hold Drill

- Hit half a bucket of balls and hold your finish for 3-5 seconds after each shot.

- Focus on balance: stay on the lead foot with chest facing the target.

2. Towel Under Arms (Connection Drill)

- Place a small towel under both armpits to maintain body connection and prevent arms from separating from the torso.

- This builds a connected finish where shoulders and arms rotate as one unit.

3. Step-Through Drill (Weight Shift Drill)

- Start with normal setup. As you swing through, step the trail foot forward to the lead foot to accentuate weight transfer.

- Promotes full hip clearance and balanced lead-side finish.

4. Slow-Motion Impact-to-Finish

- Perform slow,exaggerated swings focusing on the path from impact to full finish.

- Train the feel of extension, rotation, and controlled deceleration.

5. Alignment Stick Plane Drill

- Place an alignment stick along the shaft on the ground or one through the target line held parallel to the swing plane to encourage consistent swing path and finish line.

Common faults and Corrective Fixes (SEO keywords: common swing faults, swing fixes)

| Fault | Cause | Quick Fix |

|---|---|---|

| Early Extension | Loss of posture, hip slide | Towel behind hips; feel sitting back on heels |

| Flipping/Scooping | Early wrist release, lack of arm extension | Impact bag or pause-at-impact drill |

| Loss of Balance | Poor weight transfer | Step-through drill and balance holds |

Programmed Practice Plan (SEO keywords: practice routine, golf practice)

Structure practice to build the follow-through habit.Here’s a weekly progression suitable for most golfers:

- Warm-up (10 minutes): Mobility, soft wedges, short putts.

- 30 minutes – Drill-focused session: 3 sets of 15 shots per drill (Finish Hold, Towel Under Arms, Step-Through).

- 20 minutes – Targeted ball striking: 3 clubs (wedge, 7-iron, driver), focus on maintaining the finish for each shot.

- short game (20 minutes): Chipping and bunker play while finishing the stroke in a balanced position.

- Practice frequency: 3 focused sessions per week + 1 light refresh session to maintain motor patterns.

Metrics to Track Progress (SEO keywords: consistency, shot dispersion, ball speed)

- Shot dispersion: Track direction and dispersion pattern on range or with launch monitor.

- Launch conditions: Monitor ball speed, launch angle, and spin rate to see if better finishes lead to improved energy transfer.

- Impact location: Use face tape or impact stickers to measure centre strikes vs. heel/toe misses.

- Balance score: Count how many swings you can hold a balanced finish for 2-3 seconds during a practice set.

Case Study: From Inconsistent Contact to Sharper Ball Striking (SEO keywords: case study, ball striking)

Player: Mid-handicap amateur (index ~12). Main issue: frequent thin shots and inconsistent distance with irons.

- Assessment: Early extension and scooping at impact.

- Intervention: 6-week plan focusing on towel-under-arms drill, step-through drill, and slow-motion impact-to-finish reps. Integrated short-range launch monitor checks twice a week.

- Outcome: Centered impact frequency improved from ~45% to ~72%; average approach shot dispersion reduced by 18 yards; perceived confidence on approach shots increased.

Coaching Cues and Mental reminders (SEO keywords: coaching cues, golf mindset)

- “Finish like you’re pointing to the flag” - keeps the body aimed and chest rotated.

- “Rotate, don’t reach” – emphasizes using the body rather of flipping the hands.

- “Quiet head; loud hips” – head stability with active hip rotation produces clean impact and a stable finish.

- Breathing cue: Exhale through impact to reduce tension and promote a natural follow-through.

Putting It Into On-Course Use (SEO keywords: on-course consistency, course management)

Translating practice to the course requires applying finish-focused mechanics under pressure:

- Pre-shot routine: Use two practice swings that emphasize finish hold and rhythm.

- Short-game adaptation: Even on chips and pitches, track the finish - consistent finishes lead to consistent trajectories.

- Tempo under pressure: Use a simple tempo count (1-2 or 1-2-3) to keep rhythm and finish intact during competitive situations.

Equipment and Physical Considerations (SEO keywords: flexibility, strength, club fitting)

Physical fitness and equipment influence follow-through quality:

- Mobility: Hip and thoracic rotation flexibility help you reach a full, athletic finish without early extension.

- Strength: Core and glute strength support stable weight transfer and controlled deceleration.

- Club fitting: Proper shaft length and lie angle help the hands release correctly and finish on plane.

Quick Reference Drill Chart

| Drill | primary Benefit | Reps |

|---|---|---|

| Finish Hold | Balance & rotation | 3×15 |

| Towel Under Arms | Connection & posture | 3×12 |

| step-through | Weight transfer | 3×10 |

Final Programming Tips (SEO keywords: practice plan, follow-through mastery)

- Prioritize quality over quantity: 200 committed reps with perfect finish beats 500 mindless swings.

- Mix drills and ball-striking: Alternate between technique drills and on-target shots to reinforce transfer of skill.

- Use technology judiciously: Launch monitors and video can confirm that the visual feel matches measurable improvements.

- Track small wins: Improved balance holds, more centered impacts, and tighter dispersion are real indicators of follow-through success.

Use these biomechanics-backed techniques and structured drills to turn your follow-through into a reliable, repeatable part of your golf swing – one that consistently produces distance, control, and confidence on the course.