Golf performance is the product of an ongoing interaction between technique, physical capacity, and nervous-system control.Improving both output and durability-understood hear as maximizing on-course performance while reducing injury risk-requires a coordinated, evidence-informed strategy. Advances in three-dimensional motion analysis, force measurement, and wearable sensors have clarified which biomechanical features most strongly influence an effective swing, while modern exercise science has sharpened training approaches that develop the physical traits linked to greater distance, tighter dispersion, and lower injury rates. Integrating these fields allows coaches and clinicians to translate laboratory findings into individualized, practical training plans.

Essential biomechanical contributors include orderly segmental sequencing,precise temporal‑spatial kinematics,purposeful ground-reaction force production,and efficient conversion of angular and linear momentum into clubhead velocity. Because swings differ by style,body shape,and equipment,objective evaluation is essential: 3D motion capture,force plates,and inertial sensors (IMUs) are now commonly used to measure sequencing,timing,and loading. simultaneously occurring, the prevalence of overuse complaints-especially low back, shoulder, elbow, and wrist problems-reinforces the need to balance performance goals with load management and tissue‑specific conditioning.

best-practice golf conditioning therefore blends progressive strength and power growth, targeted rotational mobility and thoracic control, sensorimotor and balance work, and golf-specific plyometrics and motor-learning drills inside a periodized plan. High-quality programs are assessment-led, apply progressive overload that matches swing demands, and include objective monitoring to limit excessive exposure.The sections below summarize contemporary biomechanical and physiological evidence and convert key insights into actionable training and rehabilitation recommendations for improving golf-specific fitness, performance, and resilience.

Kinematic and Kinetic Foundations of the Golf Swing: Movement Signatures That Drive Distance and Precision

Modern studies using synchronized motion capture and force platforms separate the swing into two complementary perspectives: kinematics – the spatial paths and timing of body segments (positions, velocities, accelerations) – and kinetics – the forces and moments that create those motions. Although applied sources sometimes blur these terms, distinguishing them clarifies why visually similar swings can yield very different results. High-fidelity 3D kinematic data expose the sequencing of segments (pelvis → thorax → lead arm → club),while kinetic traces quantify ground reaction impulses and joint moments that deliver energy to the clubhead.

Drive distance is tightly linked to both how large and how well-timed force and angular velocity peaks are. Repeated analyses identify several consistent movement predictors:

- Initiated pelvic rotation with delayed trunk separation (a larger X‑factor and effective stretch‑shortening across the obliques)

- Fast, appropriately timed peak angular velocities in proximal segments (a clear proximal‑to‑distal timing pattern)

- Substantial, correctly oriented ground reaction force (GRF) impulses applied through a stable lower‑limb base

- Well‑timed wrist and forearm release that generates top clubhead speed without harmful sideways bending

Shot accuracy depends less on absolute power and more on the reproducibility of kinematics and low variability in timing and alignment. Kinematic indicators that predict directional control include a consistent swing plane, minimal late lateral center-of-mass shift, and tight standard deviations in segmental peak times. Think of the system like a finely tuned relay race: each segment hands off energy in sequence, and variability in the handoff degrades the final result.

For practitioners planning interventions, combining kinematic and kinetic data informs periodization and drill choice. Emphasize progressive force development (e.g., hip-drive strength and plyometrics) together with timing drills designed to improve proximal‑to‑distal sequencing and reduce within-swing variability. Recommended measurement approaches pair synchronized 3D motion capture or markerless systems with force platforms or wearable IMUs to capture segment angular velocities and GRF vectors; track both absolute outputs (for power profiling) and coefficients of variation (for consistency).Programs that raise force capacity while tightening kinematic timing typically deliver the greatest improvements in both distance and precision.

Musculoskeletal Determinants of Performance and injury: Evaluating Mobility, Stability, and Tissue Tolerance

Performance and susceptibility to injury in golf arise from an integrated musculoskeletal profile where joint range, segmental control, and the load-bearing capacity of soft tissues interact to define technical execution and durability.Mobility is meaningful only if it can be used: adequate thoracic rotation, sufficient hip internal rotation, and useful ankle dorsiflexion provide the mechanical freedom to create a compact coil and forceful unwind. Stability – especially lumbopelvic control and scapular-thoracic coordination – channels that mobility into repeatable sequencing and safe deceleration. Tissue capacity (tendon stiffness, muscular endurance, and maximal force) determines how much load can safely be exposed repeatedly without failure.

Systematic testing converts these concepts into practical priorities. A pragmatic assessment battery often includes the following elements and clinical interpretations:

- Thoracic rotation test: seated or standing range; restriction often produces compensatory lumbar twist and elevated spinal shear.

- Hip internal rotation ROM: measured with a goniometer or inclinometer; deficits can lead to premature hip clear or lateral sway during the downswing.

- Single‑leg squat / Y‑Balance: screens dynamic control and asymmetry; weaknesses predict altered ground‑force transfer and elevated knee/hip loading.

- Overhead deep squat / shoulder rotation: assesses shoulder girdle and thoracic mobility that influence club path and deceleration mechanics.

- Tendon and muscle capacity tests: repeated eccentric loading or submaximal holds to estimate fatigue resistance and tolerance to training volume.

These outcome measures provide objective thresholds to guide mobility work, motor‑control progressions, and staged tissue‑loading plans.

Typical deficits produce predictable mechanical and clinical consequences. When mobility, stability, or tissue resilience is lacking, compensations emerge that both blunt performance (reduced clubhead speed, poorer sequencing, less accuracy) and concentrate stress on vulnerable tissues (lumbar facets/discs, rotator cuff, medial elbow).The table below condenses common deficit‑mechanism pairings to help prioritize interventions during program design.

| Observed Deficit | Typical Mechanical Result | Primary Intervention |

|---|---|---|

| Reduced thoracic rotation | Excessive lumbar extension or early arm casting | Thoracic mobility drills and sequencing re‑education |

| Compromised single‑leg stability | Inefficient ground‑force transfer and lateral weight shift | Progressive unilateral strength and motor‑control work |

| Low tendon load capacity | Overuse symptoms after sudden volume increases | Isometric to eccentric loading progressions for tendons |

Training must be specific and closely monitored to safely change these variables. Program priorities follow the assessment: restore limiting range, normalize lumbopelvic and scapular control to refine sequencing, and incrementally load tendons and muscles to raise capacity without provoking flare-ups. Practical programming rules include:

- Individualized progression: begin with pain‑free isometrics and motor‑control tasks before introducing high‑speed swings or heavy rotational loads.

- Combine mobility with control: employ active drills that integrate range and stability (for example, resisted thoracic rotations) to produce usable motion.

- Monitor load: log objective volume/intensity and simple subjective markers (RPE, focal soreness) to avoid abrupt exposure increases.

Adhering to these principles turns assessment data into measurable performance gains and more robust injury prevention.

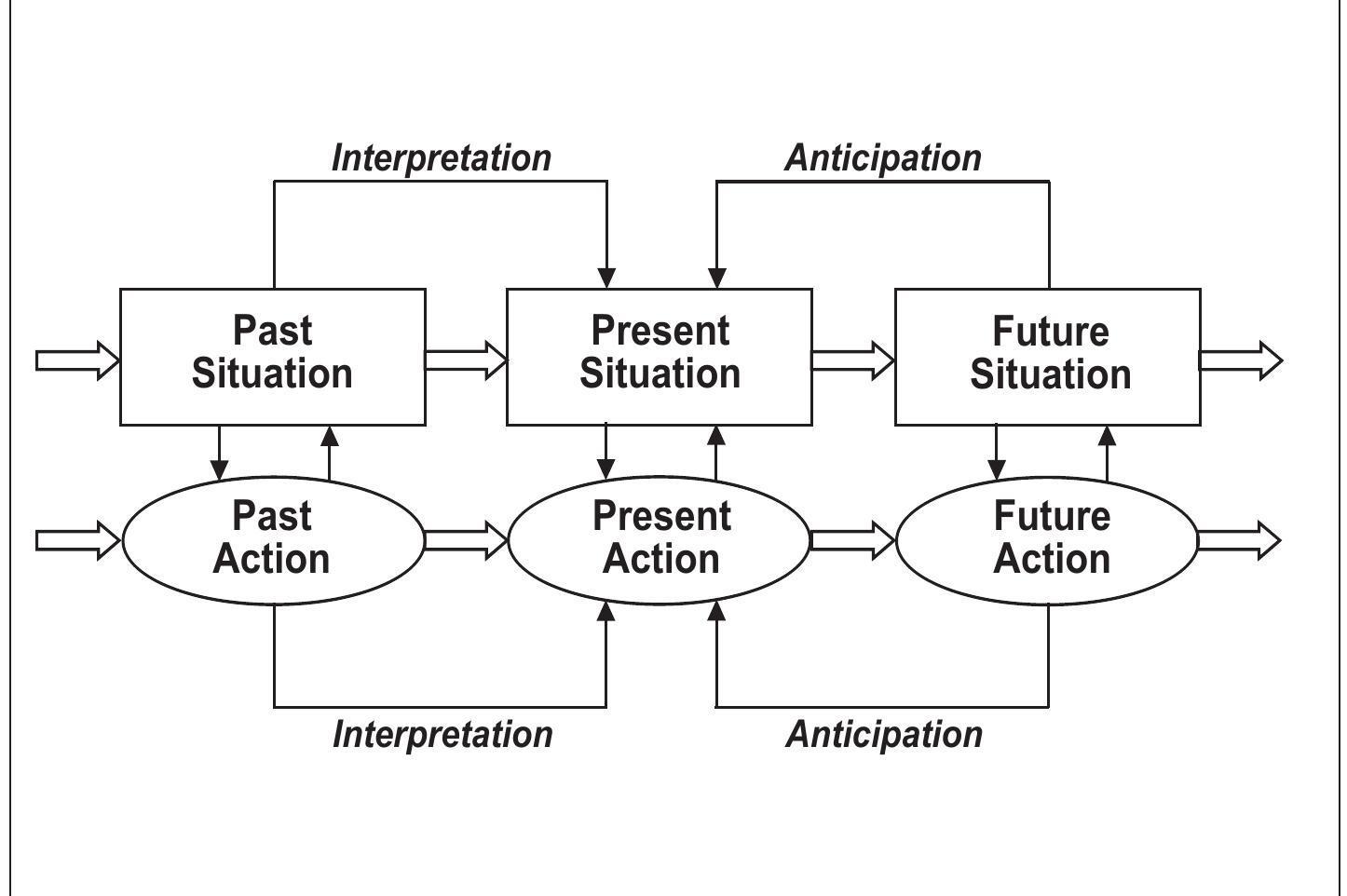

Neuromuscular Coordination & Swing Sequencing: Training to Improve timing and Energy Flow

Neuromuscular control orchestrates the timing and magnitude of muscle activations across the kinetic chain and is central to efficient swing sequencing. Optimal performance requires a repeatable proximal‑to‑distal activation pattern, precise intersegmental timing, and low trial‑to‑trial variability. In mechanical terms, good sequencing minimizes energy loss and channels rotational and linear impulse into the clubhead; breakdowns (delayed hip rotation, premature shoulder braking) create “leaks” in the system that reduce distance and directional control.

Training should therefore combine motor pattern refinement with rate‑of‑force development work. Evidence‑backed approaches include task‑specific, constraint‑led drills and high‑velocity overload exercises that emphasize timing relationships over isolated strength gains. Practical modalities are:

- Medicine‑ball rotational throws focusing on a rhythmic hip→shoulder transfer;

- Band‑resisted downswing to exaggerate late distal acceleration;

- Tempo and metronome practice to stabilize sequencing across variable loads.

Progress these drills by increasing movement complexity, external perturbations, and intent so the motor program becomes both robust and adaptable.

Structure sequencing work inside periodized cycles that balance neuromuscular priming, maximal velocity efforts, and recovery. A practical session block might include:

| Block | Objective | Example load/Tempo |

|---|---|---|

| Neuromuscular priming | Activate ballistic pathways | 3 × 6 explosive med‑ball throws |

| Sequencing drills | Refine proximal→distal timing | 4 × 8 band‑resisted swings (controlled tempo) |

| Speed‑strength | Improve rate of force | 5 × 3 plyometric steps/swings, maximal intent |

Objective measurement and timely feedback are critical for consolidation and injury reduction. Use multimodal monitoring – high‑speed video,IMUs,and selective surface EMG – alongside simple field metrics such as split‑sequence timing and clubhead acceleration. Key variables to track include:

- Sequence onset latency (hip → torso → arms);

- Timing of peak angular velocities relative to impact;

- Intertrial variability as an index of motor stability.

Ongoing measurement enables targeted adjustments (for example, more reactive drills if hip latency persists) and supports a data‑driven progression that improves timing, energy transfer, and long‑term durability.

Strength, power and Endurance for Golfers: Exercise Choices, Loading, and Periodization

Define strength as the capacity to produce and tolerate force – this guides exercise selection for golf. Choose functional, multi‑planar movements that mirror swing demands: bilateral and unilateral hip extension (Romanian deadlifts, split squats), anti‑rotation and rotational trunk work (cable chops, Pallof presses), and scapular control (rows, face pulls). Prioritize integrated patterns over isolated single‑joint moves to boost transfer.typical movement categories are:

- Force‑dominant: barbell deadlift, trap‑bar deadlift, loaded step‑ups

- Power‑dominant: rotational medicine‑ball throws, kettlebell swings, jump squats

- Stability / endurance: Pallof presses, single‑leg RDLs, farmer carries

Prescription varies by neuromuscular target. For maximal strength use higher intensities (≈85-95% 1RM),low repetitions (3-6 reps),and longer rest (2.5-5 minutes). Power work prioritizes intent and velocity with moderate loads (approximately 30-70% 1RM for ballistic lifts or velocity targets of 0.3-0.6 m·s−1),low reps (1-6) across multiple sets (3-8) and full rest to preserve speed. Muscular endurance for posture and tournament stamina typically uses lighter loads (40-60% 1RM), higher reps (12-20+) or time‑under‑tension circuits with short rests.Progression should manipulate load, speed, volume, and density – not only heavier weights.

Program architecture must respect the golf calendar. A useful macrocycle: off‑season focus on hypertrophy → strength (8-16 weeks), a pre‑competition phase shifting to power and speed (4-8 weeks), and an in‑season maintenance phase that preserves intensity and speed while reducing volume. Weekly frequencies often fall in the zone of 2-3 strength sessions and 1-2 dedicated power sessions,combined with mobility and conditioning. Reduce training volume 7-10 days before key events to allow peaking while lowering injury risk.

Objective tracking and clear progression rules enhance both safety and results: monitor bar/clubhead velocity, session RPE, movement quality, and soreness. Velocity‑based thresholds or percentage bands are useful for auto‑regulation. A simplified 12‑week example block might resemble:

| Weeks | Primary focus | Intensity | Volume |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1-4 | Hypertrophy / technical strength | 65-75% 1RM | Moderate (3-5 sets × 8-12) |

| 5-8 | Max strength | 80-92% 1RM | Low reps (3-6),moderate sets |

| 9-12 | Power / speed conversion | 30-60% (ballistic) / 70-85% (speed‑strength) | Low reps,high intent (1-6),multiple sets |

Mobility,Flexibility and Thoracic Rotation: Practical Progressions to Expand Functional Swing Range

Thoracic rotation is a primary biomechanical contributor to an effective golf swing: it increases separation between shoulders and pelvis,reduces compensatory lumbar shear,and allows higher clubhead speed without excessive low‑back motion.Contemporary analyses link restricted thoracic rotation to a smaller X‑factor and greater lateral bending, both of which hurt accuracy and raise injury likelihood. For clinicians and coaches the objective is twofold: restore usable segmental range and preserve intersegmental control so increased motion becomes productive in the swing. Restore thoracic mobility before loading rotational power, as applying heavy speed work on a hypomobile thoracic region can shift harmful stresses to the lumbar spine and shoulder complex.

Choose drills that are specific, repeatable, and tied to swing mechanics.Evidence‑informed options include thoracic extensions over a foam roll, quadruped open‑book rotations, band‑assisted seated turns, and wall‑based rib mobilizations; soft‑tissue work to the posterior cuff, latissimus, and pec minor often removes barriers to motion. For acute mobility work use conservative, high‑frequency dosing (e.g., 3-5 minutes of focused mobilization repeated 2-3 times daily), progressing toward integrated strength and speed drills. Practical exercises include:

- Foam roller extensions – hold 30-60 s segments to build extension tolerance.

- Quadruped open‑book – 8-12 controlled reps per side emphasizing scapular retraction.

- Band‑assisted rotations – 2-3 sets of 6-10 reps with gradual increases in load and velocity.

Progressions should follow a mobility→strength→power continuum that ties range gains to functional torque and speed. A simple three‑phase model is practical for programming and athlete dialog: mobility (restore usable range), strength (generate rotational torque across the trunk), and power (translate range and strength into coordinated, high‑velocity rotation). Use criteria‑based progression – only advance when pain‑free range and sound segmental control are demonstrated under low load. An example micro‑progression might be:

| Phase | Focus | Typical Sets × Reps |

|---|---|---|

| Mobility | Thoracic extension & rotation | 3 × 10-15 (daily) |

| Strength | Rotational control with load | 3-4 × 6-8 (2-3×/week) |

| Power | Med‑ball throws / club‑speed drills | 4-6 × 3-5 (explosive) |

integrate these gains into golf‑specific motor patterns: move from isolated thoracic drills into coordinated pelvis‑to‑shoulder sequencing under varied speeds and perturbations. Emphasize tempo control, correct pelvic lead, and maintaining spinal neutrality during acceleration.On‑course transfer drills might include shadow swings focusing on upper‑torso rotation without lateral bend, med‑ball throws timed to the transition, and short‑game tempo work that reinforces safe deceleration. Continually monitor for substitution patterns (excess lumbar rotation, scapular hitching) and prioritize movement quality – usable range in service of coordinated sequencing – rather than raw degrees of rotation. When mobility, strength, and motor control are developed together, a golfer gains usable range while lowering injury risk.

Injury Prevention and Rehabilitation: Structured Screening, Load Management, and Return‑to‑Play Criteria

Baseline screening should be consistent, repeatable, and sensitive to common golf injuries (lumbar spine, shoulder, elbow, wrist). Start with a focused history that separates acute from chronic presentations and screens for red flags (neurologic change, progressive weakness, systemic symptoms). Objective measures should include multi‑planar lumbar and hip ROM, thoracic rotation, scapular control tests, shoulder rotational strength, single‑leg stability, and a movement‑based swing screen. For junior players include growth‑plate considerations; for older golfers screen for degenerative conditions (such as, spinal stenosis) if neurogenic signs are present.

Load‑management systems combine quantitative and qualitative inputs to adjust exposure and reduce injury probability. Useful monitoring tools include:

- objective volume metrics (daily swing counts,practice minutes,rounds played),

- session RPE or simple soreness scales,

- planned periodization with scheduled deloads,and

- targeted warm‑up and recovery prescriptions (mobility,neuromuscular activation,sleep and nutrition guidance).

When symptoms occur, apply graduated modifications (reduce volume, adjust technique, increase recovery) and follow evidence‑based treatment pathways rather than immediate sport cessation unless red flags require urgent care.

A rehabilitation pathway should be criterion‑based and multidisciplinary: symptom control and tissue protection → restore pain‑free range → progressive strength and eccentric capacity → retrain coordinated rotational power and sequencing → sport‑specific reintegration. Use graded return to golf tasks (putting → chipping → half swings → full swings → practice rounds) and combine neuromuscular retraining with technical corrections. The table below outlines stages and objective milestones commonly used to guide progression.

| Stage | Focus | Objective milestone |

|---|---|---|

| Early | Pain management & mobility | Resting pain ≤2/10; near‑normal ROM |

| Strength | Eccentric control & load tolerance | ≥90% limb symmetry on isometric/isokinetic tests |

| Functional return | Rotational power & sport drills | Pain‑free simulated swings and graded swing volume |

Return‑to‑play decisions should be clear, measurable, and agreed among player, clinician, and coach. Minimum criteria typically include pain‑free full range of motion, objective strength symmetry (commonly ≥90% LSI), restored dynamic multi‑planar control, and reproducible, biomechanically acceptable swing mechanics under progressive loading. field tests such as medicine‑ball rotational throws, single‑leg balance with perturbation, and high‑speed swing simulation – together with psychological readiness screening – help determine readiness for unrestricted competition. Documented, metric‑based progression and explicit discharge criteria reduce re‑injury risk and align practice with modern sports‑medicine guidance.

Bridging Biomechanics and On‑Course Training: Monitoring, Technology and Practical Implementation for Sustainable Gains

Long‑term betterment depends on connecting laboratory biomechanical insight with the real‑world demands of the course. Objective monitoring tools distil complex kinematic and kinetic data into straightforward coaching targets. Core technologies include IMUs, high‑speed video, launch monitors, force plates, and wearable GPS/accelerometry devices; each sheds light on different aspects of technique, power, and on‑course movement. Combine multiple data streams rather than relying on a single measure to build a robust profile of strengths, limitations, and session variability.

- IMUs: rotational velocities and sequence timing

- Launch monitors: club/ball speed,smash factor,launch conditions

- Force platforms: ground reaction timing and weight‑shift patterns

- Video analytics: segment alignment and symmetry checks

Interpreting outputs requires mapping biomechanical metrics onto on‑course objectives and injury risk.Establish individualized baselines and normative bands to contextualize changes over time; prioritize trends and variability over single‑session peaks. Key metrics to follow include peak angular velocities (pelvis, thorax), sequence consistency, vertical/horizontal GRF impulses, tempo variability, and acute:chronic load ratios for practice volume. the compact reference below links common metrics to practical on‑course aims:

| Metric | On‑course implication | Practical target |

|---|---|---|

| Pelvic peak rotation | Contribution to driving distance | Session‑to‑session stability within ±10% |

| Ground reaction impulse | Efficient power transfer | Progressive increase during strength phases |

| Tempo variability | Consistency under pressure | Coefficient of variation < 8% |

For implementation, emphasize phased, task‑specific practice that preserves ecological validity.Alternate controlled, instrumented technical work with on‑course scenarios that include time pressure, uneven lies, and cognitive load. A practical workflow: perform short, focused technical sets in bays equipped with IMUs and launch monitors, then transfer the learned patterns into simulated course play. Use concise external‑focus coaching cues,short objective feedback windows (30-60 s video/metric review),and progressive overload in the strength and mobility plan to maximize motor learning and physiological adaptation. Weekly operational steps might include:

- baseline testing and target setting with multidisciplinary input

- Microcycles pairing strength/power days with specific swing quotas

- Periodic on‑course validation drills to confirm transfer

- Weekly review of variability and readiness data with the athlete

Sustained improvement depends on continuous monitoring of both performance and injury signals. Build simple dashboards that aggregate key indicators (cumulative swings, acute:chronic practice ratio, asymmetry indices) and flag deviations beyond individual thresholds for clinician review. While automated systems can triage alerts, expert interpretation remains essential – contextual factors such as travel, sleep, and recent coaching loads often explain metric shifts. Keep an iterative cycle of assessment, targeted intervention, on‑course validation, and reassessment; teams that combine high‑quality measurement with pragmatic coaching and conservative load management produce the most durable outcomes. Data‑informed, coach‑led integration is the practical route to long‑term performance and resilience.

Q&A

Note: the supplied web search results were unrelated to this topic. The following Q&A is distilled from recent biomechanical, physiological, and strength‑and‑conditioning literature and is presented in a practical, professional style.

Q1: What is the central biomechanical principle that determines effective and repeatable golf swing performance?

A1: At its core, an effective repeatable swing depends on orderly energy transfer through the kinetic chain – the proximal‑to‑distal kinematic sequence. Performance hinges on coordinated timing and magnitude of rotational and translational motions from the legs and pelvis,through the trunk and shoulders,into the arms and club. Ground reaction forces, segmental angular velocities, and the ability to modulate segment stiffness are primary determinants of both speed and control.

Q2: How do ground reaction forces (GRFs) and lower‑body mechanics contribute to clubhead speed?

A2: GRFs provide the external impulse that initiates momentum transfer up the body. Proper weight shift, vertical and lateral force request, and timed GRF delivery during the downswing create pelvis rotation and high proximal angular velocities. Strong, coordinated lower‑body extension and hip rotation allow larger net joint moments and higher pelvic angular speeds, which then precede trunk and upper‑limb rotation – collectively increasing clubhead velocity.

Q3: What is the kinematic sequence and why is it vital?

A3: The kinematic sequence is the temporal order and relative magnitude of peak angular velocities across adjacent segments (commonly pelvis → trunk → lead shoulder → lead arm → club). An efficient sequence shows increasing peak velocities distally with minimal reversal. Deviations – as a notable example,early arm acceleration or reduced pelvic rotation – break the handoff of energy,decrease clubhead speed,and increase load on passive structures,raising injury risk.Q4: Which physical qualities most reliably predict golf performance (e.g., clubhead speed, ball velocity)?

A4: Key predictors include maximal strength (particularly hips and lower body), rate of force development (RFD), rotational power, trunk stiffness control, and usable mobility (hip rotation and thoracic rotation). Neuromuscular coordination and sport‑specific power (such as medicine‑ball rotational throws) are also strong correlates of clubhead speed and ball velocity.

Q5: What objective tests are recommended for assessing golf‑specific physical capacities?

A5: A comprehensive battery can include: clubhead and ball speed via launch monitor; GRF profiling with force plates or single‑leg force/time tests; medicine‑ball rotational throw distance/power; isometric/isokinetic trunk rotation strength and RFD measures; lower‑body strength tests (1RM squat or valid submaximal estimates); single‑leg balance and Y‑Balance; mobility screenings (thoracic rotation, hip internal/external rotation, ankle dorsiflexion); and swing sequence assessment via motion capture or high‑speed video. Select tests based on athlete level and resource availability.

Q6: what mobility restrictions are most commonly associated with swing faults and injury?

A6: Frequently observed restrictions include limited thoracic rotation/extension, reduced lead hip internal rotation, short/overactive hip flexors or glutes affecting pelvic tilt, and restricted ankle dorsiflexion.These constraints can provoke compensatory lumbar rotation/extension, altered sequencing, and higher shear/compressive loads on the lumbar spine and shoulders.

Q7: How should a golf‑specific training program be structured (phases and priorities)?

A7: Periodize training through phases: Foundation – restore mobility, motor control, and correct gross asymmetries; Strength – develop maximal force in the lower body, posterior chain, and trunk; Power/RFD – convert strength into high‑velocity rotational and linear outputs; Sport‑specific Transfer – blend technical swing work with loaded/unloaded drills; Maintenance/Peaking – preserve force and velocity while focusing on recovery and skill practice. In‑season programming typically reduces volume and prioritizes recovery and power preservation.

Q8: Which exercises have the best evidence for transfer to golf performance?

A8: Exercises with good transfer include multi‑joint lower‑body lifts (deadlift, squat variations), single‑leg RDLs, rotational medicine‑ball throws (standing and step‑through), anti‑rotation Pallof variations, rotational cable chops, loaded rotational deadlifts, and plyometrics emphasizing horizontal/rotational force. Improvements in lower‑body strength and RFD are commonly associated with increases in clubhead speed.

Q9: How should strength and power training be dosed for golfers?

A9: General guidance: 2-3 strength sessions per week focusing on compound lifts during structured blocks (6-12 weeks), with intensity adjusted by phase (70-90% 1RM range). Power work 1-3 times weekly using low to moderate loads with maximal intent (e.g.,med‑ball throws,jump variations),sets of 3-6 reps,and ample rest for quality. Tailor conditioning volume individually and scale back frequency in‑season to avoid interference with skill work.

Q10: How can clinicians and coaches reduce injury risk in golfers?

A10: Use comprehensive screening to detect mobility limits, strength asymmetries, and swing faults.Address modifiable risks with targeted thoracic/hip mobility, posterior chain strengthening, core control and eccentric capacity for deceleration, and technical corrections to improve sequencing.Monitor overall workload, progress loads gradually, ensure adequate recovery, and introduce variability to prevent repetitive overload. Educate golfers to report symptoms early.

Q11: What role does trunk stiffness and core function play in both performance and injury prevention?

A11: Controlled trunk stiffness supports efficient energy transfer and shields the lumbar spine from excessive shear. However, excessive passive stiffness can limit rotation; insufficient active control leads to early segment motion and load concentration. Training should enhance dynamic stiffness – the ability to produce and modulate core stiffness across speeds and loads – through anti‑rotation, rotary power, and controlled eccentric/isometric work.Q12: How should rehabilitation post‑injury be integrated with return to golf?

A12: Rehabilitation should progress through stages: pain control and mobility restoration; rebuilding strength and endurance; retraining dynamic trunk control and rotational power in controlled planes; incremental return to swing mechanics and simulated practice; and objective return‑to‑play criteria (pain‑free swing, strength and function symmetry, ability to reproduce pre‑injury metrics). Decisions should be collaborative among medical, strength, and coaching staff.

Q13: Are there population‑specific considerations (youth, seniors, high‑handicap vs elite)?

A13: Yes. Youth programs should prioritize movement quality, neuromotor skill development, and age‑appropriate strength work – avoid maximal lifts before maturation. seniors need extra focus on mobility,balance,preservation of muscle mass,and carefully dosed strength/power work to sustain swing speed while protecting joints. Recreational, high‑handicap golfers frequently enough gain large relative benefits from basic mobility, core control, and strength improvements; elite players require nuanced power development, refined recovery strategies, and highly individualized plans.

Q14: What technological and methodological tools are most useful for advancing golf biomechanics and training?

A14: Valuable tools include 3D motion capture (including markerless options), high‑speed video, IMUs and on‑body sensors for on‑course monitoring, force plates for GRF analysis, launch monitors for ballistic outputs (club/ball speed, launch angle, spin), dynamometry for strength/RFD testing, and electromyography for activation studies. Machine learning and advanced signal processing increasingly support individualized prescription from large datasets.

Q15: What are the main limitations and gaps in current research?

A15: key limitations are small samples, mixed participant skill levels across studies, a lack of long‑term randomized trials directly linking training modalities to on‑course outcomes, and inconsistent reporting of training dose. More longitudinal work is needed on injury prevention, inclusion of female golfers, and translating lab findings into field‑relevant contexts including fatigue.

Q16: How should coaches integrate biomechanical findings into practical coaching without overcomplicating skill acquisition?

A16: Prioritize simple, actionable cues that address the main deficits identified in testing (for example, improve weight shift, enhance thoracic rotation, sequence pelvis before shoulders). Use objective metrics to monitor progress but distill them into easy‑to‑perform drills and clear external cues. Apply motor‑learning principles (blocked to variable practice, external focus, gradual specificity) and collaborate with physiotherapists and S&C professionals to ensure technical changes are supported by physical readiness.

Q17: what are evidence‑based warm‑up and pre‑round routines for golf?

A17: Effective warm‑ups mix dynamic mobility, activation, and gradual ballistic work: 5-10 minutes light aerobic activity, dynamic thoracic and hip mobility, posterior‑chain/glute activation (band walks, bridges), progressive med‑ball rotational throws (low → high intensity), and a few submaximal → maximal swings focused on sequencing. Tailor the routine to age, injury history, and environmental conditions.

Q18: What practical takeaways should practitioners applying this evidence keep in mind?

A18: Core takeaways: 1) Assess before prescribing – identify mobility, strength, and sequencing deficits; 2) build a base of mobility and posterior‑chain strength before adding speed; 3) train the whole kinetic chain, emphasizing lower‑body strength, trunk control, and rotational power; 4) use objective metrics (clubhead speed, med‑ball power, GRF, symmetry indices) to track progress; 5) prioritize recovery and load management to limit overuse injury; 6) individualize programs and integrate coaching, conditioning, and medical input.

If useful, I can:

– produce a concise one‑page practical checklist for coaches and clinicians;

– design an assessment battery and a periodized 12‑week sample program tailored to elite, recreational, senior, or junior golfers;

– compile a short bibliography of primary studies and systematic reviews that support these recommendations.

optimizing golf fitness demands an integrated, evidence‑centred approach that merges biomechanical insight, physiological conditioning, and targeted training prescription. Practically, this means identifying and developing the physical capacities that support efficient swing mechanics and power transfer while minimizing injury exposure. Current evidence supports prioritizing thoracic and hip mobility,co‑developing motor control and strength,and converting those qualities into rotational power through carefully periodized training.

Coaches and clinicians should use objective assessments (motion analysis, force‑platform data, validated functional tests) to set baselines, guide interventions, and monitor adaptation. Emphasize movement quality before heavy loading, integrate multi‑planar power work with preparatory strength, and apply structured load management and recovery strategies.rehabilitation and prevention should be guided by the same biomechanical principles used for performance training so that therapeutic gains transfer to play.

Research gaps remain in long‑term, field‑based intervention trials and broader inclusion across populations. Advances in wearable and portable assessment technology offer promise for bringing lab‑level precision to the course. Ultimately, effective golf optimization is a multidisciplinary, iterative process: combine high‑quality measurement with pragmatic coaching and individualized programming to maximize performance and preserve health.

Power, Precision, Longevity: Science-Backed Golf Fitness for a Better Golf Swing

Pick a tone – refined headline options (choose one and I’ll refine)

Below are the same headline concepts, tuned to four tone styles (scientific, performance-driven, practical, promotional).Pick the tone you like and I’ll hone the wording for your website or social content.

- Scientific

- Swing Science: Biomechanics and Training Protocols to Optimize Golf Performance

- Performance-driven

- Elite Swing Blueprint: Biomechanics, Physiology & Training to Increase Distance and Accuracy

- Practical

- From Mechanics to Muscles: A Practical Guide to Golf Fitness and Injury Prevention

- Promotional

- drive Further, Play Longer: Proven Golf Fitness Strategies Backed by Science

Short headline ideas for social posts / SEO-pleasant

- Short (social): “Drive Further, Play longer”

- SEO-friendly: “Golf Fitness: Biomechanics, Strength & Injury Prevention”

- Micro (tweet / IG): “Unlock Your Best Swing”

Why biomechanics and physiology matter for golf performance

Golf is a sport of precision powered by coordinated whole-body movement. Swing biomechanics describes how joints, muscles, and segments (pelvis, thorax, arms) move and transfer energy to the clubhead. Physiology-strength, power, endurance, and neuromuscular control-determines how well the body executes those mechanics. Combining both disciplines with sport-specific training is the fastest path to more consistent ball striking, higher swing speed, and reduced injury risk.

Key concepts every golfer and coach should know

- Kinetic chain: efficient energy transfer starts at the ground, flows through the hips and torso, and finishes at the hands. Breaks in the chain reduce clubhead speed and accuracy.

- Sequencing & timing: Proper pelvis-thorax separation (X-factor) and timed torso rotation produce rotational power while minimizing stress on the low back and shoulders.

- rotational power vs linear strength: Heavy squats help general strength, but golf-specific power comes from rotational medicine-ball throws, anti-rotation drills, and single-leg stability work.

- Mobility-stability balance: Adequate thoracic rotation and hip internal/external rotation allow safe, effective swing positions; core and scapular stability protect the spine and shoulder.

- Load management & recovery: Repetitive practice without recovery leads to overuse injuries. Periodization and active recovery are essential.

Screening and assessment – what to test

Before designing a program, conduct a simple golf-specific screen. These tests are low-equipment, high-payoff and identify mobility or strength deficits to address.

- functional movement screen (simple version)

- Single-leg balance (30 sec eyes open)

- Deep squat mobility (knees, hips, ankles)

- Overhead reach / thoracic rotation

- Shoulder external rotation and scapular control

- golf-specific tests

- Seated trunk rotation (range & quality)

- Pelvic rotation vs thoracic rotation (X-factor assessment)

- Medicine-ball rotational throw (power proxy)

- Swing speed and ball flight monitoring (launch monitor or radar)

- Clinical flags: Persistent low back pain, shoulder pain, or joint instability should get referred to a physiotherapist or sports medicine provider before high-load training.

Evidence-based training components for golf fitness

1) Mobility & tissue prep

prioritize thoracic rotation,hip internal/external rotation,ankle dorsiflexion,and shoulder girdle mobility. Use dynamic warm-ups and targeted mobility sessions 3-5 times per week.

- World’s Greatest Stretch (with thoracic rotation)

- 90/90 hip switches and controlled banded hip distractions

- Band-assisted scapular and shoulder circles

- Cervical and thoracic foam rolling for neural mobility

2) strength & hypertrophy (foundation)

Two strength sessions per week focusing on lower-body, posterior chain, and unilateral work build a robust base-improves stability and reduces injury risk.

- Squats (progress from goblet to barbell)

- Romanian deadlifts / hip thrusts

- Single-leg Romanian deadlifts,split squats

- Rows and horizontal pull variations for scapular control

3) Power & rotational speed (transfer to swing)

Power training should be explosive,specific,and low-volume: medicine-ball rotational throws,cable chops,and kettlebell swings. These drills convert strength to swing speed.

- Rotational MB throw (standing and kneeling)

- Cable woodchops and anti-rotation holds

- Explosive single-leg hops for ground reaction force timing

4) Motor control & swing-specific drills

Integrate tempo work, impact position training, and rhythm drills that encourage proper sequencing and timing.Use impact bags, swing meters, and on-course situational practice.

5) Conditioning & energy systems

Golf requires low-level aerobic conditioning and brief anaerobic bursts. Maintain cardiovascular fitness with low-impact steady-state cardio and interval work (e.g., 20-30-minute bike or row sessions, HIIT sparingly). This supports recovery across multi-day tournaments.

Sample 6-week golf fitness micro-cycle (WP table)

| Week | Focus | Key Sessions |

|---|---|---|

| 1 (Assess) | Screening & mobility | Mobility daily / Strength 2x / Low-power throws |

| 2 | Strength base | Full-body strength 2x / mobility / light rotational power |

| 3 | Power introduction | strength 2x / Power 2x (MB throws) / On-course tempo work |

| 4 | Intensify | Strength heavier / Power faster / Sprint or intervals |

| 5 | Speed & transfer | Low-load, high-speed swings / MB throws / On-course practice |

| 6 (Taper) | Sharpen & recover | Short power sessions / Mobility / Course simulation |

Sample exercise progressions and sets/reps

- Strength: 3-4 sets x 6-8 reps (compound lifts), 2x/week

- Power: 3-5 sets x 3-6 reps (explosive), 1-3x/week

- Mobility: 8-12 min daily targeted work

- On-course tempo drills: short sessions integrated during practice rounds

Injury prevention – where golfers most commonly get hurt and how to avoid it

Most golf injuries occur in the low back, wrist, elbow, and shoulder. Risk factors include poor mobility, weak core/hip musculature, over-practice without recovery, and sudden spikes in intensity.

Prevention strategies

- Address thoracic rotation and hip mobility deficits early.

- Prioritize eccentric hamstring strength and hip extension to support the downswing and follow-through.

- Build scapular stability and rotator cuff endurance to protect the shoulder during repeated swings and practice sessions.

- Use load monitoring-track RPE, volume, and swing counts. Avoid >10-20% weekly spikes.

- Include regular soft tissue work and mobility to keep the kinetic chain functioning.

Training considerations by golfer type

Weekend warrior / amateur

- Emphasize mobility and basic strength. Two strength sessions + 10-15 minutes of mobility per day yields large returns.

- Prioritize recovery after rounds-active recovery like walking or bike rather of full rest days.

Competitive amateur / low-handicap

- Focus on power transfer, swing speed training, and fine-tuned motor control. Add specific on-course rehearsal under fatigue.

- Monitor swing speed regularly and periodize practice towards peak events.

Seniors / older golfers

- Lower-impact conditioning, joint-friendly strength work, elastic power (medicine-ball), and more frequent mobility sessions to preserve longevity.

- Emphasize balance exercises and single-leg stability.

Monitoring progress – KPIs to track golf fitness gains

- Swing speed (mph or km/h)

- Ball carry distance and dispersion (accuracy)

- Medicine-ball throw distance / explosive power

- Movement screen scores (thoracic rotation, single-leg balance)

- Subjective measures: RPE, soreness, sleep, and daily readiness

Practical tips for immediate improvements

- Start each practice with a 8-12 minute dynamic warm-up that includes thoracic rotation and hip activation.

- Make one change at a time-add mobility for 2-3 weeks, then introduce strength or power work.

- Use mirrors or video to link feeling to movement-record the downswing and check pelvis-to-torso sequence.

- integrate swing-speed days by using lighter clubs in swift, controlled swings to train fast-twitch recruitment.

- Hydrate, prioritize sleep, and schedule active recovery-these amplify training adaptations.

Case study – translating science into outcomes (example)

Golfer: 48-year-old competitive amateur with 95-100 mph driver swing speed and chronic low back stiffness. Baseline screen showed limited thoracic rotation and weak single-leg hip stability.

- Intervention: 8-week program – thoracic mobility drills (daily), strength (2x/week), rotational medicine-ball work (1-2x/week), single-leg balance & glute activation.

- Results: +6 mph driver swing speed, 12-15 yards increased carry, reduced low back soreness, improved consistency on approach shots. The athlete reported greater swing confidence and less fatigue over 36-hole days.

Resources and tools

- simple tools: medicine ball (4-10 kg), resistance bands, kettlebell, foam roller, and a launch monitor (if budget allows).

- Apps & tracking: use a training log or app to record sets/reps, swing speed, soreness, and course performance.

- When to seek help: persistent pain, notable asymmetry, or poor progress warrant a physiotherapist or certified golf fitness coach.

SEO & content strategy tips for publishing this material

- Use primary keywords in title tags and H1 (e.g., “golf fitness”, “golf strength”, “swing biomechanics”).

- Write descriptive meta descriptions under 160 characters – we included one above.

- Use schema where possible (Article, BlogPosting) and include internal links to related content (e.g., swing tips, nutrition for golfers, injury rehab).

- Create supporting pieces: “5 mobility drills for golfers”, “3-week golf power plan”, and short video demos for higher engagement and longer time-on-page.

- Optimize images (alt text: “golf fitness medicine ball rotational throw” etc.) and add captions with keywords.

Want this tailored?

If you want, tell me the audience (beginner, competitive amateur, senior), preferred tone (scientific, performance-driven, practical, promotional), and platform (blog post, landing page, Instagram caption). I’ll refine the headline, craft a short SEO-friendly tagline, and produce a tailored 6-8 week training plan with progressions and exhibition links.