Enhancing performance in the golf swing depends on translating biomechanical theory into concrete,measurable objectives that coaches and athletes can train toward. Here,”optimizing” is taken to mean refining movement strategies so they deliver maximal effectiveness and efficiency-balancing force generation,directional control,and long‑term tissue health. Modern evaluation uses quantitative measures of motion, force, muscle activity, and energy flow to reveal constrained movement patterns, timing errors between segments, and inefficient force application that limit clubhead velocity and shot precision.

This review combines approaches from biomechanics, wearable and lab sensors, and data science to outline a systematic workflow for objective appraisal and tailored intervention. By pairing 3D motion capture, inertial measurement units (IMUs), force platforms, EMG, and musculoskeletal simulation with statistical and machine‑learning tools, practitioners can extract actionable indicators-timing of peak segment angular velocities, effectiveness of proximal‑to‑distal sequencing, ground‑reaction force signatures, and joint loading trends-that translate into coaching cues and training protocols. The goal is to move past subjective description and into reproducible, evidence‑based adjustments that raise performance while lowering injury risk across ability levels.

Segment Timing and Coordination in the Golf Swing: Measuring and Improving the Proximal‑to‑Distal Cascade

Efficient energy transfer from the body into the club depends on a clearly ordered, time‑sensitive activation of body segments-a proximal‑to‑distal cascade. in high‑level swings the hips begin the downswing rotation, followed by the torso, then the upper arm, forearm and finally the hands and clubhead. This staged release builds angular velocity at the club while reducing wasted intersegmental counterwork. Practitioners quantify this pattern via onset latencies, peak angular velocity timings and rhythmic coupling metrics that together describe how seamlessly momentum flows through the kinetic chain. Preserving the timing integrity of the sequence is as crucial as the magnitude of joint rotations for both distance and accuracy.

An objective assessment couples kinematic and kinetic data: optical systems or IMUs deliver accurate segment orientations and angular velocities while force plates and force‑line sensors provide ground‑reaction timing and joint moment estimates. Note the conceptual difference between kinematics (motion and timing) and dynamics (forces and torques); both perspectives are necessary to diagnose timing faults. Frequently tracked temporal markers include:

- Hip initiation: start time relative to address and time‑to‑peak rotation.

- Torso lag: delay versus pelvis that indicates fidelity of energy hand‑off.

- Arm/hand release: peak wrist angular velocity and release timing that influence club speed.

- Foot‑force timing: vertical and horizontal impulse patterns that lead or accompany hip drive.

Coaching refinements use drills and real‑time feedback to modify the width of these timing windows toward empirically supported ranges. Practical methods include tempo work (metronome or auditory cues), separation drills that highlight torso‑hip dissociation, and resisted or assisted swings to alter time‑to‑peak values. The compact template below summarizes commonly used temporal targets in applied settings-individual baselines should always guide prescription rather then fixed global norms.

| segment | Relative Onset (% of downswing) | Typical Time-to-Peak (ms) |

|---|---|---|

| Pelvis | 0-10% | ~120-180 |

| Thorax | 10-30% | ~140-200 |

| Arms | 30-70% | ~160-220 |

| Hands/Club | 70-100% | ~180-260 |

In practice adopt an iterative,measurement‑led workflow: establish baseline timing,select interventions aimed at specific phase durations,then re‑test with the same sensor setup. Use kinematic coupling-defining clear control points and limiting extraneous motion-to simplify the motor solution while conserving dynamic output. The objective is not to impose a single “perfect” sequence on every golfer but to refine each player’s temporal coordination so that energy travels predictably, efficiently and repeatably from the ground through the body into the clubhead.

Ground Reaction Forces and Weight Transfer: How Lower‑Limb Mechanics drive clubhead Velocity

Evidence from kinetic studies shows a strong link between clubhead speed and both the magnitude and timing of lower‑limb ground reaction forces (GRFs). force‑platform research demonstrates that efficient swings transform vertical and horizontal GRF components into rotational impulse through coordinated hip and trunk motion. Typical mechanical markers include a fast rise in vertical force under the trail foot during loading, a medial‑to‑lateral shift of center‑of‑pressure at transition, and a stabilizing bracing impulse on the lead limb instantly before impact. Emphasize concepts such as rate of force development (RFD), impulse, and COP transfer when converting kinetic profiles into training actions.

Coaching recommendations to increase lower‑limb contribution cover stance geometry, timing cues, and sequenced movement patterns. Use a stance that balances stability and mobility (moderate width, slight toe‑out) and coach purposeful loading of the trail leg prior to downswing initiation. Common, effective cues include:

- “Load, then push” – delay lateral transfer until the trail leg has accumulated compression and potential energy.

- “Brace the lead leg” – create a stiff but elastic support with the lead limb at impact to convert rotation into clubhead speed.

- “explosive lateral drive” – convert stored vertical/trail impulse into medial‑lateral drive during transition.

Objective benchmarks from lab and applied studies give useful targets for training; practitioners should tune these to the athlete’s body size and skill level.Representative field/lab metrics include:

| Metric | typical Target | When Measured |

|---|---|---|

| Peak vertical GRF (lead limb) | ~1.2-1.8 × bodyweight | Impact window (~−50 to +10 ms) |

| medial‑lateral impulse | Clear positive impulse at transition | ~100-200 ms around transition |

| RFD (trail limb) | Maximized within ~150 ms | Loading phase |

Turn kinetic findings into a progressive training plan that blends neuromuscular conditioning, technical drills and tempo work. Effective interventions include resisted lateral push‑offs to amplify medial drive, single‑leg bracing exercises with rotational follow‑through to enhance impact stiffness, and tempo‑restricted swing sets to refine the timing of weight transfer. Sample drill sequence:

- Loaded lateral step + rotate: emphasize trail‑leg compression and rapid medial transfer.

- Force‑plate feedback swings: short blocks with immediate GRF cues to embed bracing timing.

- Power circuit: unilateral squat jumps, Romanian deadlifts, and rotational medicine‑ball throws focused on transferability.

Trunk and pelvic Mechanics: Rotation, Tilt and Stability for Repeatable Contact

Reliable ball striking depends on controlled dissociation between the pelvis and thorax: the right amount of separation stores elastic energy while preserving the geometry at impact. Greater thorax‑pelvis separation (the X‑factor) can increase theoretical clubhead velocity, but only when frontal‑plane tilt and lateral control are maintained. Excessive rotation without appropriate axial tilt or with uncontrolled pelvic drop increases variability in attack angle and face alignment, compromising accuracy. Thus evaluations must account for three‑dimensional orientation and the timing relationships that form the impact snapshot, not just peak rotation magnitudes.

Quantitative assessment with motion capture or IMUs should extract metrics such as peak pelvic rotation, peak thorax rotation, X‑factor at the top of the backswing, pelvic sagittal tilt, and lateral bend. The compact reference below summarizes commonly observed ranges in high‑level samples and thresholds for intervention:

| Metric | Typical Range | Performance note |

|---|---|---|

| Pelvic rotation (backswing) | ~30°-50° | Too little reduces power; too much can disrupt sequence |

| Thorax rotation (backswing) | ~60°-100° | Contributes to X‑factor potential |

| Pelvic tilt (sagittal) | ~5°-12° | Helps preserve consistent low‑point and attack angle |

Stability and timing largely determine repeatability: the pelvis must rotate and then decelerate so angular momentum transfers controllably to the torso and arms. Train corrective priorities that restore dependable sequencing and center‑of‑mass control:

- Pelvis control: maintain rotational mobility while limiting lateral drop.

- Axial tilt: preserve forward tilt to safeguard attack angle and impact height.

- Temporal sequencing: ensure the hips initiate the downswing at an appropriate time to maintain a proximal‑to‑distal chain.

These priorities can be tracked with accessible field measures (onset time differences, trunk‑pelvis angular‑velocity ratios) and inform intervention selection.Effective drills include resisted pelvic rotations to improve control, wall‑brace tilt drills to maintain sagittal orientation, and split‑stance accelerations to refine timing. Set specific, measurable goals from assessment (such as, decrease lateral pelvic drop by X° or increase thorax‑pelvis separation at the top by Y°) and monitor progress with periodic motion capture or wearable IMU checks. Combining constraint‑led cues (e.g., “start the downswing with the hips”) with quantified targets produces the most consistent improvements in impact repeatability and shot dispersion.

Upper‑Limb and Wrist Mechanics: Techniques to Manage Face Angle and Reduce Overuse

Proximal‑to‑distal sequencing remains crucial for clubface control: coordinated scapulothoracic rotation, glenohumeral external rotation and timely elbow extension set the stage for wrist mechanics to fine‑tune face orientation. Research and theory both show that preserving a controlled wrist hinge (lag) through the downswing stores elastic energy and reduces the need for last‑moment wrist flicks that destabilize the face. equally critically important is balanced grip pressure-an overemphasized ulnar‑side squeeze or uneven tension correlates with unwanted face rotation and elevated stress on the distal radioulnar joint and wrist extensor tendons.

Operationalize evidence‑based technical changes with repeatable drills and cues focused on timing and load distribution. Useful strategies include:

- Delayed‑release practice – pause at the top and focus on preserving wrist lag through transition for a controlled release.

- Towel‑under‑arms drill – a towel between the arms and torso encourages coordinated shoulder-elbow-wrist motion and limits self-reliant wrist flicking.

- Impact‑pad strikes – short, progressive contacts that emphasize a slightly dorsiflexed lead wrist at impact to stabilize loft and face.

- Grip‑pressure mapping – use simple pressure devices or biofeedback to balance radial/ulnar loading and avoid over‑gripping.

These practices shift force generation proximally,lowering compensatory wrist torques that increase performance variability and overuse injury risk.

| Kinematic Parameter | Practical Target | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Lead wrist at impact | Neutral to slight dorsiflexion (~0-10°) | Stabilizes loft and reduces face opening |

| Trail wrist hinge | Sustained radial deviation through transition | Maintains lag and elastic energy storage |

| Grip pressure | moderate and balanced, finger‑dominant | Reduces compensatory wrist torque and tendon load |

Reducing injury risk requires targeted conditioning and careful load management alongside technical changes. Emphasize eccentric strengthening for wrist extensors and flexors, combined concentric/eccentric work for forearm pronator‑supinators, and rotator cuff and scapular stabilizer conditioning to disperse club‑derived loads.Progressively reintroduce new release patterns or higher swing speeds with staged exposure and screen athletes for limited distal radioulnar mobility, excessive radial/ulnar deviation, and painful tendinopathy. Use objective monitoring (video kinematics, grip‑pressure sensors, validated pain and function scales) to ensure performance gains do not come at the cost of cumulative tissue overload.

Sensor Protocols and Data Integration: best Practices for Reliable Swing Assessment

Whether in the lab or the field, protocols must protect repeatability and signal fidelity. Control the surroundings (consistent lighting, minimal reflective surfaces for optical systems, fixed hitting location for launch monitors) and log sensor geometry and calibration parameters. Run static calibration trials to define joint centers and segment axes, and perform dynamic checks (walking or standardized swings) to confirm marker/IMU coherence. Document ambient conditions and athlete setup (footwear, club model) in a session log to support cross‑session comparisons.

sensor choice and placement determine the granularity of usable metrics. Combine high‑speed optical capture (≥200 Hz) for club and distal segment trajectories with body‑worn IMUs (200-1000 Hz) for field robustness and force plates (≥1000 Hz) for GRF quantification. When using skin‑mounted markers or IMUs, follow consistent anatomical landmarking (ASIS, PSIS, lateral femoral condyle, acromion) and secure hardware to limit soft‑tissue artifact. For representative data record at least 8-10 valid swings after a standardized warm‑up and exclude initial adaptation swings from analysis.

Preprocessing and synchronization are essential before interpretation. Use hardware or software triggers to align optical, IMU, force and launch monitor streams and confirm alignment with an event (e.g., impact spike). Apply appropriate low‑pass filtering for each sensor domain (Butterworth or zero‑lag filters; kinematics typically 6-20 hz, higher cutoffs for forces and IMU angular rates), correct for IMU drift, and compute derived quantities with validated inverse‑dynamics pipelines. Produce both continuous time‑series and event‑based summaries (backswing peak, transition, impact, follow‑through) and report intra‑session variability to contextualize change.

Analysis should map objective metrics to coaching actions and athlete goals. Prioritize sequence indicators (hip→torso rotational onset and peak order), mechanical outcomes (clubhead speed, smash factor), and impulse measures (vertical/horizontal GRF peaks, RFD). Benchmark individual profiles against normative or role‑specific reference bands and include confidence intervals for key measures. Deliver concise, actionable recommendations-e.g.,prescribe mobility work if X‑factor is limited or redistribute foot force if impulse timing is off-so biomechanical insight converts into practical coaching steps.

- Minimum sensor suite: optical cameras + IMUs + force plate / launch monitor

- Sampling recommendations: optical ≥200 Hz, IMU 200-1000 Hz, force ≥1000 Hz

- Trial structure: standardized warm‑up, 8-10 analyzed swings, exclude first 2 adaptation swings

- Quality checks: synchronization confirmation, marker‑gap thresholds, and residual analysis after filtering

| Sensor | Primary output | typical Hz |

|---|---|---|

| optical motion capture | 3D marker trajectories, club path | 200-500 |

| IMU | Segment orientation, angular rates | 200-1000 |

| Force plate | Ground reaction forces, COP | 1000+ |

| Launch monitor | Clubhead speed, ball metrics | 250-2000 |

From Data to Practice: Drills, Progressions and Periodization Grounded in Biomechanics

Biomechanical frameworks-from movement mechanics to tissue loading-provide a practical roadmap for turning lab findings into on‑course improvements. Motion‑capture and force‑plate analyses isolate measurable limitations (for example, reduced pelvis‑thorax sequencing, low ground reaction impulse, or mistimed wrist release) that relate to lower clubhead speeds and increased dispersion. Translational training turns these quantities into targetable performance variables and prescribes drills that reproduce the temporal and spatial demands seen in effective swings while respecting individual anatomy and tissue capacity.

Choose evidence‑based drills that isolate,then integrate,kinetic and kinematic elements. Representative exercises include:

- Rotational medicine‑ball throws – encourage proximal‑to‑distal acceleration and improved RFD.

- step‑through weight‑shift swings – promote timely lateral force transfer and GRF production.

- Band‑assisted lead‑arm control – reinforce scapulothoracic stability and consistent face orientation at impact.

- Metronome tempo training – regularize downswing timing and reduce inter‑trial variability.

- Impact‑pad compression reps – practice wrist release and compressive energy transfer under realistic loads.

Progress each drill from low‑load, high‑control variations to faster, higher‑load versions as motor control and tissue tolerance improve.

Periodize technical,physical and recovery priorities across macro‑,meso‑ and microcycles to maximize transfer of biomechanical improvements to competition. A practical model: an off‑season macrocycle (8-12 weeks) focusing on hypertrophy and eccentric control; a pre‑season mesocycle (4-8 weeks) emphasizing ballistic power and speed‑specific strength; and in‑season microcycles dedicated to maintenance, technical polish and freshness. within each block alternate high‑intensity neuromuscular sessions with low‑intensity technical work, and schedule objective testing blocks every 4-6 weeks. Respect chronobiological and schedule constraints, use conservative load progressions (for example, 5-10% weekly increments for power/velocity metrics) and plan deloads to reduce injury risk while consolidating motor learning.

monitoring and decisions should be metric‑driven and reproducible. Use a multimodal battery (3D capture/IMU for sequencing and clubhead speed, force plates for impulse measures, and validated accuracy tests under pressure).Key performance indicators can be organized simply:

| KPI | Metric | Practical Target |

|---|---|---|

| Sequencing | Pelvis→Thorax time lag (ms) | Target ~80-120 ms |

| Power transfer | Peak ground reaction impulse (N·s) | Progressive +10% vs baseline |

| clubhead speed | max mph (or m/s) | Incremental sport‑specific gains |

Recommended monitoring cadence: a full baseline battery before a training block, fortnightly rapid checks with IMU/launch monitor, and a full retest at block conclusion. Define decision rules (for example, reduce load if pain appears or if sequencing consistency worsens by >10%) so interventions stay athlete‑centered and evidence‑based.

Injury Prevention and Return‑to‑play: Screening, Load Management and Clearance Criteria

Comprehensive musculoskeletal screening underpins any swing‑optimization plan. A pre‑participation assessment should combine medical history (prior injuries, recurring pain), clinical examination (joint ROM, spinal mobility) and functional tests (single‑leg balance, rotational control) to uncover modifiable risk factors. Evidence on sports injury risk highlights both intrinsic factors (strength deficits, mobility limitations) and extrinsic contributors (training load, equipment). Core screening elements include:

- History & red flags: prior lumbar, shoulder or elbow pathology; persistent pain during swings

- Movement quality: thoracic rotation and hip internal/external rotation symmetry

- Strength/endurance: trunk rotators, hip abductors/adductors and scapular stabilizers

Load‑management bridges the gap between capacity and performance by adjusting volume, intensity and frequency of swing work. Apply progressive overload with variation in repetition count, club speed and resistance training to build tissue tolerance while limiting cumulative microtrauma. Monitoring can be low‑tech (session RPE,swing counts) or high‑tech (IMUs,force‑plate derived kinetics,EMG). Practical strategies include:

- Incremental progression: small weekly increases (10-20% for new stressors) with scheduled deloads

- Cross‑training: strength and mobility sessions to redistribute load away from vulnerable joints

- objective monitoring: RPE × duration, peak swing velocities, and symptom tracking for early warning

Rehabilitation and return‑to‑swing decisions should be criterion‑based. Advance athletes from controlled drills to full swings only when pain‑free mechanics, restored range and functional strength symmetry are documented. Use the checklist below as a practical clearance guide:

| Criterion | Objective | Minimal target |

|---|---|---|

| Pain | Symptom provocation with swing tasks | VAS ≤1 during graded swings |

| Range of Motion | Thoracic and hip rotation symmetry | ≤10% side‑to‑side difference |

| strength | Rotational and scapular endurance | ≥90% limb symmetry index |

| Load tolerance | Progressive full‑speed swings without symptom flare | 2 consecutive sessions at target volume |

Long‑term success requires a multidisciplinary approach that aligns coaches, physiotherapists, strength staff and the athlete around common metrics. Emphasize maintenance: periodized strength, mobility routines and technique tweaks informed by periodic biomechanical feedback to prevent recurrence. Practical ongoing checkpoints include:

- Regular re‑screening: quarterly or after any new pain episode

- Data‑driven changes: adjust technique or load when objective metrics decline

- Education: ensure the athlete understands symptoms, recovery timelines and safe progression

Q&A

Below is a concise, research‑oriented Q&A to accompany an article on optimizing the golf swing with biomechanical methods. answers focus on rigorous methods, critical metrics, practical translation to coaching, and common limitations. Where relevant the generalized meaning of “optimizing” is noted with standard dictionary references.Q1. What does “optimizing” the golf swing mean in biomechanical terms?

A1. Within this framework, “optimizing” means deliberately refining the swing so that it achieves defined performance outcomes-higher ball speed and carry, improved accuracy, greater repeatability and reduced injury likelihood-using objective, measurable criteria. This aligns with dictionary definitions of optimize as making something as effective or functional as possible (Merriam‑Webster; Cambridge; Collins).

Q2. What is biomechanical analysis and why is it useful for improving the swing?

A2. Biomechanical analysis applies mechanics and physiology to quantify movement. For golf it yields objective data on kinematics (positions, velocities), kinetics (forces, moments) and neuromuscular timing (EMG), enabling identification of limiting factors, mechanisms of power transfer and injury risk-supporting targeted, data‑driven interventions instead of guesswork.

Q3. Which technologies are central to collecting golf‑swing biomechanics?

A3. Typical tools include:

– Optical motion capture (marker‑based or markerless) for 3D kinematics

– IMUs for portable segment tracking

– Force plates/pressure mats for grfs and weight transfer

– High‑speed video for qualitative and 2D analysis

– EMG for muscle timing and magnitude

– Launch monitors (radar/photometric) for club and ball outcome metrics

– Integrated force + motion systems for inverse dynamics

Q4. What key biomechanical metrics should be tracked?

A4. Core metrics include:

- Clubhead and ball speed

– Kinematic sequence and peak segment angular velocities

– X‑factor and X‑factor stretch

– Ground reaction forces and RFD

– Center‑of‑mass displacement and stability

– Swing plane, face‑to‑path and impact kinematics

– Temporal variables (backswing/downswing duration, tempo)

– Muscle activation timing and symmetry

– Variability measures (trial‑to‑trial standard deviation, coefficient of variation)

Q5. How is the kinematic sequence defined and why is it important?

A5. The kinematic sequence captures the temporal order and relative magnitudes of peak angular velocities across segments (usually pelvis → thorax → arms → club). An effective proximal‑to‑distal sequence maximizes transferred energy to the club and limits compensatory loads; deviations can signal inefficiencies or compensatory strategies.

Q6. What analysis methods are commonly used?

A6. Analysts typically apply:

– Time‑series preprocessing (filtering, normalization to events such as impact)

– Inverse dynamics for joint moments and power

– Statistical models (repeated‑measures ANOVA, mixed models)

– dimensionality reduction (PCA, functional PCA)

– Cross‑correlation and causality analyses for timing

– Machine learning models (supervised regression/classification) for predictive tasks

– Signal decomposition (wavelets) for time‑frequency features

– Reliability metrics (ICC, SEM) to assess measurement stability

Q7. How should signals be preprocessed for valid results?

A7. steps include sensor synchronization, resampling to a common rate, low‑pass filtering with cutoffs chosen from signal bandwidth, IMU drift correction, temporal normalization to key events, and normalization of kinetics/EMG to bodyweight or MVIC.Document preprocessing choices to ensure reproducibility.

Q8. How do you convert biomechanical findings into coaching actions?

A8. The process is: (1) identify specific deficits (e.g., late pelvis rotation), (2) choose evidence‑based interventions (technique cues, drills, conditioning), and (3) set measurable targets and feedback (e.g., increase pelvis angular velocity by X deg/s or reduce pelvis‑thorax lag by Y ms). Reassess with the same measures to quantify adaptation.

Q9. Which physical qualities most influence swing mechanics?

A9. Important factors include thoracic and hip rotational mobility, core stiffness and torque transfer ability, lower‑limb force production and transfer, ankle/hip stability for weight shift, and motor control for dependable timing and tempo. Programs should be individualized based on assessed deficits.

Q10. How should injury risk be assessed and minimized?

A10. Combine load monitoring (volume/intensity), inverse‑dynamics joint loading estimates, and tissue‑specific risk factors (history, mobility). Use progressive overload, adequate recovery, and technical adjustments to reduce extreme joint excursions. Objective monitoring helps detect risk early.

Q11. What study designs suit research in swing optimization?

A11. Use cross‑sectional analyses for associations, longitudinal randomized or controlled intervention trials to test effectiveness, single‑subject repeated‑measures designs for individualized responses, and between‑group comparisons (skill/age cohorts) to derive norms. Ensure sample‑size planning and pre‑registration where possible.

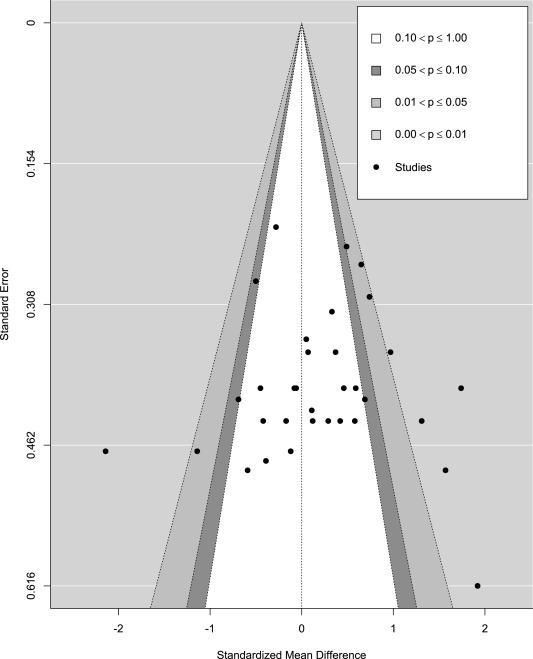

Q12. How should affect sizes and practical significance be reported?

A12. Report standardized effect sizes (Cohen’s d, partial η²) with confidence intervals and p‑values. Translate changes into practical outcomes (e.g., m/s gains in clubhead speed → m increases in carry) and compare to measurement error (smallest detectable change) to assess real‑world relevance.

Q13. What pitfalls exist in biomechanical swing studies?

A13. Common issues: limited ecological validity of lab settings, marker‑placement error, small sample sizes and low statistical power, overfitting in complex models, neglecting inter‑individual variability, and failure to consider behavioral/psychological contributors to performance.

Q14. How should machine learning be integrated responsibly?

A14. Use ML to support domain expertise. Ensure high‑quality labeled data, proper train/validation/test splits, cross‑validation, evaluation of generalizability, and interpretable models or explainability tools (e.g., SHAP). Validate on independent cohorts and report standard performance metrics (RMSE, AUC, R²).

Q15. How do you ensure reliability and validity across sessions and sites?

A15. Standardize protocols (marker sets, sensor placement, warm‑up), use calibration routines, train technicians, report intra‑ and inter‑rater reliability (ICC), and harmonize hardware/software across sites with cross‑site calibration trials.

Q16. How should interventions be prioritized from biomechanical data?

A16. Prioritize actions that: (1) address the largest limiting factor for the athlete’s goals, (2) are evidence‑supported and safe, (3) are feasible given resources, and (4) permit objective progress tracking. use a tiered approach: immediate technical fixes, concurrent physical capacity work, and motor‑learning drills for consolidation.

Q17. What ethical and data‑privacy steps are required?

A17. Obtain informed consent, clarify data use/retention, anonymize identifiable data, secure storage and transmission, and restrict access. Be obvious about commercial use and secondary analyses; for minors obtain parental consent and extra safeguards.

Q18. Which future directions look most promising?

A18. Key avenues include markerless capture and wearable sensor fusion for on‑course monitoring, real‑time biofeedback integrating kinematic/kinetic signals, personalized predictive models combining biomechanics and learning profiles, integrated studies linking biomechanics with aerodynamics and environment, and large normative databases for individualized benchmarking.

Q19.How should findings be shared with non‑expert athletes?

A19. Translate technical output into simple cues and numeric targets,use visual tools (video with overlays),and deliver biofeedback during practice.Emphasize small, measurable gains and connect interventions to meaningful on‑course outcomes.

Q20. What practical checklist should practitioners follow when starting a biomechanics‑driven program?

A20. Checklist:

– define performance and safety goals.

– Baseline assessment with standardized protocols (kinematics,kinetics,launch data).

– Identify deficits and likely causal mechanisms.- Choose evidence‑based interventions (drills, conditioning, feedback).

– implement progressive overload and objective monitoring.

– Reassess with the same measures and evaluate change against measurement error.

– Iterate and individualize based on response.

Recommended definitional references: Merriam‑Webster,Collins,and Cambridge for “optimize/optimising.” For domain‑specific methods consult current biomechanics texts and peer‑reviewed literature on golf biomechanics, motor control and sports engineering.

This updated examination highlights that ”optimizing” the golf swing-interpreted as making it as effective, efficient and functional as possible-is best achieved with a structured, data‑driven strategy. Combining high‑resolution kinematic and kinetic capture, individualized biomechanical modeling, and controlled intervention studies lets coaches isolate the movement patterns that increase clubhead velocity while preserving accuracy and protecting tissue. Practical success depends on translating those measurements into straightforward practice protocols, integrating wearables and video feedback with evidence‑based coaching, and continuously validating outcomes against both performance and health metrics.

Looking ahead, progress will rely on interdisciplinary collaboration, larger and more diverse participant pools, and harmonized measurement and reporting standards so results generalize across populations and playing conditions. Widespread adoption of markerless capture and wearable fusion, plus expanded normative datasets, will further support individualized benchmarking. Attention to language and regional spelling (“optimizing” vs “optimising”) aids international dissemination. Ultimately, the most effective path to a higher‑performing swing blends biomechanical precision with pragmatic coaching so empirical insight produces measurable, on‑course gains.

The Biomechanics blueprint: transform Your Golf Swing with Science

Pick the best headline for your audience

- Players (all levels): Unlock Explosive Drives: The Science of a Biomechanically Perfect Golf Swing

- coaches: Build a Bulletproof Swing: Biomechanical Insights for Power and Injury Prevention

- Tech-focused readers: From Data to Distance: Biomechanical Secrets to a Consistent Golf Swing

- Short/punchy option: Swing Science: Turn Biomechanical Data into Better Shots

Why biomechanics matters for your golf swing

Biomechanics-the scientific study of movement in living organisms-applies physics to how your body moves through the golf swing. Using principles from biomechanics helps players and coaches identify how forces,joint sequencing,and body alignment produce clubhead speed,launch conditions,and consistent ball striking. Understanding these principles is not just academic: it leads to measurable gains in driving distance, shot dispersion, and fewer injuries.

Core biomechanical principles that drive better golf

1. The kinetic chain: transfer energy efficiently

Your swing is a linked sequence from ground → legs → hips → torso → shoulders → arms → club. Efficient sequencing (proximal-to-distal activation) creates a whip-like effect that maximizes clubhead speed with minimal extra effort.

2. Ground reaction forces (GRF)

Pushing into the turf generates reaction forces that humans convert into rotational and linear momentum.Better GRF application-through stance, posture, and lower-body drive-generally increases distance.

3. Torque and separation (X-factor)

Maximizing the differential between hip rotation and shoulder rotation stores elastic energy in core muscles and connective tissues. Controlled separation (often called X-factor) helps produce power while preserving timing.

4. Joint mobility and stability

Healthy ranges of motion at the hips, thoracic spine, shoulders, and ankles allow optimal positions without compensatory moves that cause inconsistency or injury. Stability in the core and glutes ensures the energy transfers to the club, not into wasted movement.

5. Timing, tempo, and repeatability

Power without control is useless. Biomechanics emphasizes consistent timing of body segments and a reproducible tempo to align dynamic positions at impact, producing accurate, repeatable strikes.

Essential setup and posture: small changes, big results

- grip mechanics: Neutral-to-slightly-strong grip supports predictable clubface rotation. grip pressure shoudl be firm but not tense-think 5-6/10.

- Stance and alignment: Shoulder-width stance for driver, narrower for irons. Square or slightly open feet depending on shot shape preferences and hip mobility.

- Posture: Hinge at hips, maintain a straight spine angle, and keep slight knee flex. This posture optimizes power transfer and protects the lower back.

- Ball position: Forward for driver, centered for mid-irons – consistent ball position improves launch angle and strike location.

Measuring what matters: metrics every golfer should track

Modern coaching and self-improvement use data to diagnose problems and measure progress.Key metrics include:

- Clubhead speed (mph or kph)

- Ball speed and smash factor

- Launch angle and spin rate

- Attack angle

- Face angle and path at impact

- Hip and shoulder rotation sequencing (from motion capture)

| Metric | Why it matters | Typical target |

|---|---|---|

| Clubhead speed | Primary driver of distance | Increase gradually via technique & fitness |

| Smash factor | Efficiency of energy transfer | Driver ~1.45, Irons ~1.3-1.4 |

| Launch angle | Determines carry vs roll | Driver 10-15° (player dependent) |

| Spin rate | Controls trajectory & stopping power | Driver 1800-3000 rpm (player/club dependent) |

data-driven drills and practice plan (players and coaches)

Below are high-value drills that translate biomechanical principles into repeatable actions. use a launch monitor or smartphone video for immediate feedback.

Drill 1: The Pulse & Shift (ground force timing)

- Address, then practice a subtle lateral weight shift to trail leg (right leg for right-handers) and then a controlled pulse into the front foot during the downswing.

- Goal: feel the ground reaction push and a stable lead leg at impact.

- Reps: 10 slow-motion reps,then 20 at 75% speed.

Drill 2: X-Factor Holds (separation control)

- On the top of the backswing,hold the position and gently oscillate the torso while keeping lower body stable to feel stored torque.

- Release into a controlled downswing focusing on resolving hips before shoulders.

- Benefit: improves timing of proximal-to-distal sequence.

Drill 3: Impact Bag / Towel Drill (impact geometry)

- Hit into an impact bag or practice with a towel under the armpits to promote connection between arms and torso at impact.

- Focus on compressing (not scooping) through the ball and a forward shaft lean for crisp iron strikes.

weekly practice structure (sample)

- Warm-up & mobility: 10-15 minutes (thoracic rotations, hip openers)

- Technique session: 20-30 minutes (Drill focus – pick one)

- Data & feedback: 15 minutes (launch monitor or video)

- On-course simulation: 20-30 minutes (apply changes under mild pressure)

Fitness and injury prevention: biomechanical priorities

Biomechanics informs training plans that enhance swing mechanics and reduce injury risk.

- Mobility: Thoracic rotation and hip internal/external range are essential for separation without lumbar overuse.

- Stability: Strong glutes, core, and rotator cuff muscles stabilize joints during high-speed rotation.

- Power training: Olympic-style or plyometric movements (carefully supervised) convert strength into speed relevant to the golf swing.

- Recovery: Soft-tissue work and dynamic warmups reduce cumulative stress on the back, elbows, and shoulders.

How coaches and tech teams use motion capture and analytics

Coaches increasingly pair conventional observation with motion capture, high-speed video, and launch monitor data. This hybrid approach identifies:

- Joint angles through the swing (shoulder turn, hip rotation, wrist set)

- Sequence timing – when each segment peaks in velocity

- Face angle and path relative to the target line at impact

Research and applied biomechanics (see works summarizing biomechanics of human movement) show these objective measures allow targeted interventions that are faster and more reliable than coaching by feel alone.

Case study: small change, big impact

A mid-handicap player with inconsistent drives recorded the following baseline: clubhead speed 92 mph, average dispersion 40 yards, and high side spin. A focused six-week intervention targeted three elements: improved weight shift (drill: Pulse & Shift),reduced grip tension,and thoracic mobility work. Results:

- Clubhead speed improved to 96-98 mph

- Average dispersion reduced to 18 yards

- Smash factor and launch improved, producing ~10-15 yards extra carry

Lesson: identifying the weakest link (timing and mobility) and addressing it with biomechanical principles yielded substantial performance gains within weeks.

Common swing faults and biomechanical fixes

| Fault | Likely biomechanical cause | Fix (drill or cue) |

|---|---|---|

| Slice | Open clubface & outside-in path | Face awareness, path drill, stronger release practice |

| Hook | Closed face and early release | Delay release, weaker grip, swing path adjustment |

| Fat or thin shots | Poor low-point control, weight/pivot timing | Towel drill, impact bag, weight-shift practice |

Practical tips for applying biomechanics today

- Start with data: video your swing and/or use a launch monitor to get baseline metrics.

- Address mobility and posture before trying to add power-stability without mobility equals compensations.

- Prioritize one change at a time to preserve feel and rhythm.

- Use objective feedback (speed, launch, dispersion) to confirm progress-feel can be deceptive.

- Work with a coach who understands both teaching and biomechanics, or use tech tools that provide valid metrics.

Tools and tech worth knowing

- Launch monitors (TrackMan, GCQuad, FlightScope) – measure launch angle, spin, and smash factor.

- High-speed video + 2D analysis apps – rapid and affordable motion feedback.

- Marker-based motion capture – best for deep biomechanical analysis of joint sequencing.

- Force plates – measure ground reaction forces and weight transfer timing.

Frequently asked questions (FAQ)

Q: Will biomechanics make me hit the ball farther instantly?

A: Not always immediately. Some players see instant gains from small mechanical or sequencing fixes. For many, improvements come from combined changes to mobility, sequencing, and strength over weeks to months.

Q: Do I need expensive tech to benefit?

A: No. Basic lessons, video analysis, and consistent drills can yield large returns. Tech accelerates and refines the process,especially at higher performance levels.

Q: Can biomechanics prevent injuries?

A: Yes. By identifying harmful compensations (e.g., excessive lumbar rotation, poor hip mobility), biomechanical approaches reduce stress on vulnerable tissues and guide safer training.

Next steps: a simple 30-day biomechanical tune-up

- Week 1: Baseline testing (video + simple mobility screen).Focus on thoracic rotation and hip mobility.

- Week 2: Implement one key drill (X-Factor Holds or Pulse & Shift) and monitor changes with video.

- Week 3: Add strength/stability routine (3×/week, 20-30 minutes focused on glutes, core, and shoulder stability).

- Week 4: Re-test on a launch monitor or via tracked dispersion. Adjust and iterate.

Recommended reading & references

for background on the science behind these concepts, review foundational biomechanics resources like encyclopedic summaries of biomechanics and applied sports biomechanics literature. Those sources provide the physics-based framework supporting the practical coaching tips above.

Want this tailored into a printable coach’s checklist, a beginner’s quick-start guide, or a tech-focused whitepaper with sample motion-capture outputs? Say which audience you want and I’ll format it for you.