Contemporary coaching practice in golf increasingly emphasizes the design of practice that is both systematic and grounded in empirical evidence. This article examines structured golf drills thru the lens of motor learning, biomechanics, and applied performance research, with the aim of clarifying which practice methods reliably improve technical execution, enhance shot-to-shot consistency, and transfer to on-course outcomes. Drawing on controlled experiments,longitudinal training studies,and biomechanical analyses,the review evaluates key variables that differentiate effective drills-practice schedule (blocked versus variable),contextual interference,feedback type and frequency,attentional focus (external versus internal),task specificity,and the role of self-controlled and augmented feedback.By synthesizing findings from laboratory and field settings, the analysis identifies patterns in how drill design interacts with skill level, learning stage, and training dosage to influence retention and transfer. Practical implications are emphasized: coaches and players will find evidence-based guidelines for selecting and sequencing drills, integrating technology-driven feedback, and structuring practice sessions to maximize durable improvements in stroke mechanics and course performance. The article concludes with recommendations for measurement standards in future research and a concise framework for implementing structured, theory-informed practice routines in coaching contexts.

Note on source ambiguity: web search results returned material related to a productivity request named “Structured” (a task-planning app), which is unrelated to the topic of golf practice methods; those results do not contribute evidence to the present analysis.

Theoretical Foundations: Motor Learning principles Underpinning Structured Golf Drills

Contemporary motor learning frameworks provide a coherent theoretical scaffold for structuring golf drills. Drawing on **schema theory**, **ecological dynamics**, and data‑processing models, effective drill design emphasizes the formation of adaptable movement solutions rather than rote reproduction of a single “ideal” swing. Core principles include:

- Specificity: task constraints and perceptual information should mirror on‑course demands;

- Variability: controlled variation in practice promotes robust generalized motor programs;

- Feedback modulation: timing, frequency and informational content of augmented feedback shape learning trajectories;

- Progressive complexity: incremental increase in task and environmental complexity enhances transfer.

These principles together promote goal‑directed exploration and stable retention across contexts.

Decisions about practice schedules and structure derive directly from these theoretical underpinnings. Empirical motor‑learning contrasts-such as blocked versus random practice and constant versus variable practice-yield predictable tradeoffs between short‑term performance and long‑term transfer. The table below summarizes typical effects relevant to golf coaching (simplified for practical application):

| Practice format | Acquisition (performance) | Retention/Transfer |

|---|---|---|

| Blocked | Rapid betterment | Limited transfer |

| Random | Slower immediate gains | superior transfer |

| Variable | Moderate gains | High adaptability |

Coaches should therefore prioritize **variable, representative practice** when the objective is resilient on‑course performance, while using blocked drills selectively to isolate technique for short instructional phases.

Augmented feedback and attentional focus are central mediators of learning outcomes. The literature supports **reduced frequency** and **summary or bandwidth feedback** to prevent dependency, while emphasizing informational content that guides error detection rather than imposing explicit kinematic templates. Practical implications include:

- Faded feedback schedules – high initially, reduced over time;

- Bandwidth feedback – feedback only for errors outside an acceptable range;

- External focus cues – directing attention to ball flight or target location enhances automatic control;

- Self‑controlled feedback – granting learners autonomy improves motivation and retention.

These strategies align with principles of intentional practice and support the transition from dependency to self‑regulated correction.

Translating theory into on‑course gains requires deliberate alignment between drill design and performance criteria. The **constraints‑led approach** recommends manipulating environmental, task and performer constraints to invite functional movement patterns that are directly useful in competition. Measurement and progression should be explicit: define target metrics (e.g., dispersion, launch conditions, decision time), use representative scenarios, and iterate complexity as skill stabilizes. Coach interventions should therefore prioritize: representative task sampling, graded variability, objective measurement, and periodic transfer tests to ensure drills produce meaningful improvements under pressure.

Designing Effective Practice Sessions: Task Variability Deliberate Practice and Progression strategies

Contemporary practice design for golf integrates principles from instructional design and motor learning to optimize skill acquisition. Emphasizing **task variability** alongside high-quality repetitions enables learners to form adaptable movement solutions rather than rigid movement patterns. In this framework, variability is manipulated systematically (e.g., shot location, lie, wind simulation) to promote generalized pickup of perceptual-motor information. Conversely, **deliberate practice** components concentrate on clearly defined micro-goals, immediate feedback, and focused error-correction to refine technique when precision is required.Together these elements balance exploration and exploitation, supporting both learning transfer and technical efficiency.

Operationalizing this balance requires a structured session template that sequences exploratory and focused elements. A typical session alternates blocks devoted to:

- Variable contextual practice (simulated course scenarios, stochastic targets),

- Targeted technique drills (short, high-quality repetitions with specific feedback), and

- Integrated play (on-course or simulated competitive replications to consolidate transfer).

Within each block, manipulate task constraints (target size, time pressure, equipment) to systematically increase representativeness and challenge while preserving safety and measurable outcomes.

Progression should be planned across sessions with explicit progression criteria. The table below presents a concise three-stage progression model frequently supported in applied research: acquisition, stabilization, and transfer. Each stage pairs primary aims with simple assessment metrics to guide advancement decisions.

| Stage | Primary Aim | Example Metric |

|---|---|---|

| Acquisition | Develop consistent movement solutions | 90% drill completion accuracy |

| Stabilization | Reduce variance under mild perturbation | SD of carry distance < 5% |

| Transfer | Apply skills in representative play | Score differential vs baseline rounds |

Evaluation and iterative refinement are essential: adopt a design-oriented mindset-define objectives, prototype session variations, measure outcomes, and iterate. Use mixed feedback sources: objective metrics (dispersion, launch data), coach-led qualitative assessment, and learner self-assessment to triangulate progress. When progression stalls, adjust either the degree of variability or the specificity of deliberate practice tasks rather than increasing volume alone. this evidence-aligned, designerly approach ensures sessions remain both efficient and ecologically valid for on-course performance gains.

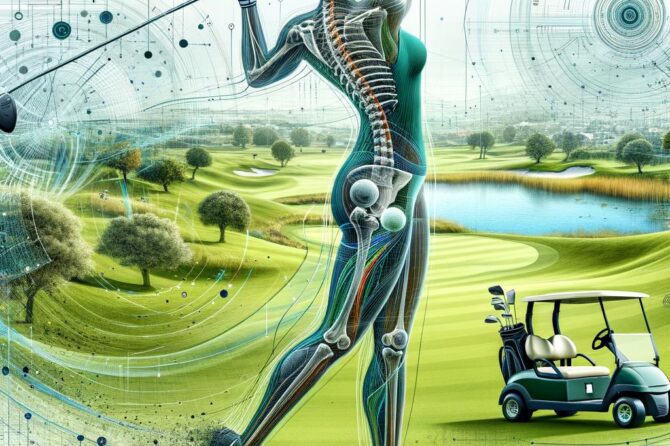

biomechanical Targets and Drill Selection: Translating Kinematic Findings into Practical Interventions

Contemporary kinematic analyses identify a finite set of high-leverage variables-trunk-pelvis dissociation, proximal-to-distal sequencing, loop and plane consistency, and impact vector alignment-that account for large portions of variance in clubhead speed and shot dispersion. Translating these empirical targets into practice requires defining **operational kinematic thresholds** (e.g., degrees of pelvic rotation, X‑factor, or peak angular velocity timing) and then selecting drills that reliably expose and train movement patterns within those thresholds. Interventions that are agnostic to these quantified targets tend to produce broad changes in feel but weak transfer to measured performance; conversely, drills explicitly linked to a kinematic target enable systematic adjustment and objective progress tracking.

An evidence-informed selection framework emphasizes specificity, constraint manipulation, and graded progression. Key principles include task-relevant specificity (drills should replicate the temporal and spatial constraints of the swing), error augmentation for rapid re-calibration, and repetition with variable practice to support adaptability. Practically, coaches can organize drills into complementary categories:

- Motor control primitives – slow, segmented practice with augmented feedback.

- tempo and timing – metronome or rhythm-based repetitions to stabilize sequencing.

- Impact and alignment – impact tape, face-target drills to refine vector control.

- Load-release sequencing – resisted or weighted implements to emphasize proximal-to-distal timing.

Below is a compact mapping of common kinematic deficits to representative drills and logical progressions. This table is intended as a practical heuristic rather than a prescriptive protocol; individualization remains essential.

| Kinematic target | Drill example | Progression |

|---|---|---|

| Delayed hip rotation | Step‑through swing (slow motion) | Increase speed → add ball → on-course reps |

| Poor sequencing (late release) | Medicine‑ball throws (horizontal) | Decrease load → swing with weighted club → impact focus |

| Inconsistent swing plane | Alignment rods / gate drill | Closed eyes reps → visual feedback → full swings |

effective translation depends on integrating measurement and feedback loops: wearable inertial sensors, launch monitor metrics, and video kinematic overlays should be used to set baselines, define stop/go criteria, and verify transfer. Frequency and dose should follow motor‑learning principles-distributed practice with interleaved variability produces greater retention than massed repetitions-while immediate augmented feedback (e.g., haptic or sonified cues) can accelerate early acquisition. The practical imperative for coaches is to couple **quantified kinematic goals** with drills that are structurally aligned to those goals and to monitor both short‑term adaptations and on‑course transfer systematically.

Measurement and Feedback: Objective Metrics Instrumentation and Augmented Feedback Protocols

Rigorous practice requires measurement that is both **reliable** and **objective** – that is, quantifiable data that is not unduly influenced by observer bias. Objective metrics such as **clubhead speed**, **ball speed**, **launch angle**, **spin rate**, and **shot dispersion** provide a common language for diagnosing performance and tracking change over time. Framing practice goals around these metrics enables instructors and players to convert qualitative coaching cues into testable hypotheses, and to apply statistical approaches (mean, variance, trend analysis) to evaluate the effectiveness of specific drills.

Instrumentation choice determines the fidelity of the feedback stream; selection should be guided by validity, reliability, and ecological fit. High-fidelity tools include launch monitors, high‑speed video systems, inertial measurement units (IMUs), force plates, and pressure mats – each with characteristic strengths and limitations. Key instrument features to prioritize include:

- Sampling rate and latency – to capture transient events within the swing;

- Calibration and validity – documented accuracy relative to laboratory standards;

- Portability and robustness – for on-course vs. laboratory application;

- Data accessibility – raw exports and common formats for downstream analysis.

Augmented feedback protocols should be structured to support learning phases: novices benefit from more frequent, prescriptive feedback while advanced learners require reduced frequency and more summary-style cues to promote retention and transfer. Employ a combination of **concurrent** (real-time visual/haptic) and **terminal** (post-trial summary) feedback, and implement a faded schedule (high → low frequency) as skill stabilizes. Where appropriate,use bandwidth feedback (notify only when error exceeds a tolerance band) to encourage self-discovery and reduce dependency on external cues.

To integrate measurement into practice design, translate metrics into actionable targets and progress bands and embed them in iterative drill cycles. The table below offers a concise mapping of common metrics to illustrative target ranges and practical drill uses. Use automated logging to produce trend plots and confidence intervals for each metric, and adapt drill difficulty via adaptive thresholds (tighten or relax target bands) based on performance trends.

| Metric | Illustrative Range | Training Use |

|---|---|---|

| Clubhead speed | 85-115 mph | Power/swing mechanics drills |

| Launch angle | 10°-18° | trajectory control practice |

| shot dispersion | ±10-30 yd | Consistency/aim drills |

Transfer to On Course Performance: Ecological Validity and Contextual Interference Considerations

Maximizing the carryover from practice to competitive rounds requires designing drills that preserve the informational constraints of the course surroundings. Empirical frameworks such as Representative Learning Design emphasize that practice should replicate the perceptual and decision-making demands players face on course-visual variability, shot-selection options, and temporal pressure. When drills foreground perception-action coupling and situational cues, golfers demonstrate greater adaptability under competitive conditions and show improved retention of functional movement solutions.

Practice structure must deliberately manipulate variability to promote transfer. The concept of contextual interference predicts that interleaving disparate tasks (higher interference) often impairs immediate performance but enhances long-term retention and transfer. Conversely, repetitive, low-interference practice can accelerate short-term gains without guaranteeing on-course applicability. Practical implementations include:

- interleaved shot-type sessions: alternate full shots, pitch shots, and bunker shots within a single training block to mimic round variability.

- Conditioned target practice: vary wind, lie, and arrival angles to sustain perceptual problem solving.

- Pressure simulations: impose scoring consequences or crowd/noise cues to train emotional regulation and decision-making.

| Drill | Primary On-Course Target |

|---|---|

| Random-distance putting series | Green-reading & speed control |

| Mixed-tee simulation | Club selection under varied lies |

| Pressure match-play drills | Decision-making and stress resilience |

To operationalize transfer, coaches should adopt a graded approach: begin with high-fidelity task constraints to establish perceptual templates, then systematically increase contextual interference to foster robust, adaptable skills. Measurement should extend beyond technical metrics to include outcome variables such as strokes gained, shot dispersion under pressure, and decision consistency. Emphasizing representative design and calibrated contextual interference yields practice programs that not only improve mechanics but reliably elevate on-course performance.

injury Prevention and Load Management: Balancing Technique Training with Musculoskeletal Health

Contemporary practice requires that technique growth proceed in concert with structured load management to minimize cumulative tissue strain while preserving motor learning. Emphasize **periodization** of on-course, range, and gym exposures so that high-intensity technical sessions are temporally separated from heavy neuromuscular loading. Objective monitoring-daily session RPE,swing counts,and simple wellness questionnaires-provides actionable signals to adjust volume or intensity. For skeletally immature golfers, clinicians should be notably vigilant as growth plates represent biomechanically weaker regions of the musculoskeletal system (NIAMS), necessitating conservative progression and frequent re-evaluation of training dose.

specific clinical considerations should inform drill selection and progression. Repetitive wrist loading and compression can contribute to distal neuropathies such as **carpal tunnel syndrome** in susceptible individuals; thus, drills that produce sustained hyperflexion/extension under load should be modified or limited. Athletes with systemic bone‑fragility disorders (e.g., **osteogenesis imperfecta**) require individualized programming and multidisciplinary oversight. In all cases, pre-participation screening and timely medical referral for persistent pain or neurologic symptoms are essential components of risk mitigation.

Practical load‑management strategies can be embedded directly into practice design to protect musculoskeletal health without compromising motor learning. Recommended tactics include:

- Session caps: limit high‑velocity swing repetitions per session and per week;

- Progressive exposure: incrementally increase swing intensity and volume across 2-4 week microcycles;

- Cross‑training: incorporate rotator cuff, scapular, core, and hip strength work to distribute forces away from vulnerable joints;

- Active recovery: employ low‑intensity mobility and aerobic sessions on high‑load days to enhance tissue recovery.

These interventions should be prescribed with measurable targets (e.g., swing count thresholds, RPE limits) to enable objective adherence and modification.

| Common Risk | Simple Adaptation |

|---|---|

| High weekly swing volume | Rotate high‑intensity days; cap swings |

| Wrist/median nerve irritation | Modify grip/drill; early referral |

| Adolescent athletes | Reduced load progression; monitor growth pain |

| bone‑fragility conditions | Individualized, medically cleared plan |

Integration of these data‑driven adaptations within coaching practice demands ongoing reassessment: use performance metrics, pain reports, and functional tests to guide drill progression, and engage sports medicine professionals when limits are reached. This multidisciplinary, monitored approach preserves technical development while prioritizing long‑term musculoskeletal integrity.

Implementing Evidence Based Programs: Periodization Individualization and long Term Skill Retention

Program design must translate empirical principles into actionable training cycles that balance skill acquisition, consolidation, and performance under pressure. Drawing from motor learning and sport-science literature, effective plans use **progressive overload**, planned variability, and scheduled recovery to prevent maladaptive repetition and plateau.Quantitative targets (e.g.,accuracy,dispersion,tempo metrics) are linked to qualitative observations (movement patterns,pre-shot routine stability) so that adaptations are monitored with both biomechanical and outcome measures. This integration ensures that sessions are not isolated drills but structured stimuli within an overarching timeline.

Individualization is achieved through systematic assessment and iterative adjustment: baseline testing (shot dispersion, clubhead speed, launch metrics), movement screening, cognitive-perceptual profiling, and player goals form the decision matrix for drill selection and progression. Coaches should implement a constraints-led approach where task, environment, and performer constraints are manipulated to elicit desired movement solutions rather than prescribing a single “ideal” pattern. Practical recommendations include:

- Assess-standardized tests every 4-8 weeks.

- Prescribe-drills linked to identified deficits (e.g.,tempo vs. impact consistency).

- Adapt-modify variability, feedback frequency, and difficulty based on response.

Periodization for golf requires micro-, meso-, and macro-level planning that aligns technical emphasis with competition schedules and biomechanical loading capacities. Below is a concise exemplar mapping cycle to training focus and representative drill types, suitable for adaptation to individual profiles.

| Cycle | Primary Focus | Representative Drill |

|---|---|---|

| Micro (1 week) | Technique polish; error correction | Blocked reps with video feedback |

| Meso (3-6 weeks) | Skill variability; decision-making | Random-distance target games |

| Macro (season) | Peak performance & tapering | Simulated rounds with pressure tasks |

Maintaining gains over months and years requires explicit retention strategies: spaced repetition of key movement patterns, increasing contextual interference to promote durable encoding, and periodic transfer tests that assess on-course application. Feedback schedules should transition from high-frequency augmented feedback during acquisition to faded and summary feedback to support internal error detection. a maintenance plan-combining low-volume high-quality sessions, periodic diagnostic blocks, and competitive simulations-safeguards long-term performance while allowing room for technical evolution aligned with athlete maturation and changing goals.

Q&A

Note on search results: the provided web search returns pages for a productivity app named “structured,” which is unrelated to the topic of structured golf drills. No retrieved sources addressed golf. Below is an academic-style Q&A tailored to the requested article topic, “Structured Golf Drills: Evidence-Based Practice Methods.”

1.What is meant by “structured golf drills” in the context of evidence-based practice?

Answer: Structured golf drills are practice tasks deliberately designed with specific objectives, constraints, and progression rules to target defined perceptual-motor skills and decision processes. In an evidence-based framework, drills are informed by motor-learning theory (e.g., specificity, variability of practice, contextual interference), biomechanics, and empirical outcome measures (retention, transfer to on-course performance).2. What theoretical principles from motor learning underpin effective structured drills?

Answer: key principles include specificity of practice (action and environment similarity to performance), variability of practice (practice across a range of movement and task conditions to enhance generalization), contextual interference (interleaving different tasks to improve retention and transfer), appropriate feedback scheduling (faded, summary, or bandwidth feedback), and deliberate practice (goal-directed, effortful, and feedback-rich repetitions).

3. How does biomechanics inform drill design?

Answer: Biomechanical analyses identify critical kinematic and kinetic variables associated with performance (e.g., pelvis and thorax rotation timing, clubhead speed, impact conditions). Drills can be constructed to encourage movement patterns that promote stable impact mechanics and energy transfer while minimizing injury risk. Objective measures (motion capture, IMUs, launch monitors) guide drill targets and progression.

4.What empirical outcomes should be used to evaluate drill effectiveness?

Answer: Short-term outcomes: accuracy (distance to target), precision (shot dispersion, standard deviation of carry), kinematic consistency, and launch-monitor metrics (ball speed, smash factor, spin, launch angle). Longer-term outcomes: retention tests, transfer to on-course metrics (strokes gained, scoring average), and subjective measures (confidence, perceived control). Effect sizes and statistical comparisons across conditions support evidence-based evaluation.

5. How should drills be structured to maximize transfer to real play?

Answer: Emphasize representative practice-simulate decision-making, environmental conditions, and task constraints found on course. Use interleaved practice across club choices and shot types, incorporate variability in target location and lie, include time pressure and competitive elements occasionally, and use outcome-focused goals (targets, distances) rather than purely mechanical cues.

6. What is the role of feedback within structured drills?

Answer: Feedback should be task-relevant and gradually reduced to promote intrinsic error detection. Use prescriptive feedback sparingly; prioritize knowledge of results early (e.g., distance, accuracy) and move toward summary, delayed, or bandwidth feedback to foster self-monitoring. Augmented feedback can be augmented with objective data from launch monitors and video but should avoid creating reliance.7. How many repetitions and how frequently enough should structured drills be practiced?

Answer: There is no worldwide prescription; effective protocols follow principles of distributed practice and deliberate repetition. For acquisition, 200-500 purposeful swings per week distributed across sessions can be effective, with sessions of 45-90 minutes including varied task sets. Progression should be individualized based on performance plateaus, fatigue, and retention assessments.

8. How should practice variability be implemented?

Answer: Include variability across target distance, club selection, lie, wind simulation, and task goal (e.g., stroke minimization vs. target centering). Structure sessions with blocked phases for initial acquisition of novel movements and interleaved phases for consolidation and transfer. Gradually increase variability as consistency improves.

9. What experimental designs best evaluate the efficacy of structured drills?

Answer: Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) comparing structured versus conventional practice, crossover designs to control individual differences, and longitudinal cohort studies for long-term transfer. Incorporate pretest-posttest retention and transfer assessments, objective biomechanical and performance metrics, and adequate sample sizes with power analyses.

10.What measurement technologies enhance evidence collection during drills?

Answer: Launch monitors (track ball speed, carry, spin), high-speed video, three-dimensional motion capture or inertial measurement units (IMUs) for kinematics, force plates for ground reaction forces, and wearable sensors for head/torso movement.Combine objective metrics with outcome statistics (e.g., strokes gained) for thorough assessment.11. How can coaches individualize structured drill programs?

Answer: Perform baseline assessments of technique, variability, physical capabilities, and psychological factors.Set measurable short- and medium-term goals. Tailor drill selection, feedback frequency, and progression tempo according to learning style, motor variability, injury history, and on-course requirements.

12. what are effective examples of evidence-based structured drill types?

Answer:

– interleaved Club-Selection Drill: alternate shots across multiple clubs and targets to induce contextual interference and improve decision-making.

– Distance-Variation Range Routine: randomized distances for a single club to develop scaling of force and carry consistency.

– Impact-Condition Drill with Feedback: use launch-monitor targets focusing on ball speed and smash factor with faded feedback.

– Short-Game Constraint drill: varied lies and green speeds with outcome-based scoring to promote adaptive touch and read skills.

– Pressure Simulation Series: timed or leaderboard-based competition to study performance under stress.

13. How should progress and mastery be assessed?

Answer: Use objective thresholds (e.g., reduction in carry distance SD by x%, improvement in shots within a target radius), retention tests after 24-72 hours, and transfer tests on-course. Evaluate effect sizes, confidence intervals, and individual responder analyses. Use repeated measures to monitor trends.

14. What common pitfalls should practitioners avoid?

Answer: Overreliance on blocked repetition that limits transfer, excessive prescriptive technical cueing that reduces self-regulation, ignoring physical limits and fatigue, insufficient variability, and failure to measure retention or transfer. Also avoid interpreting short-term improvements as long-term learning without retention data.

15. What is known about the time course of learning from structured drills?

Answer: Acquisition gains can appear rapidly, but true learning requires retention and transfer, which benefit from spaced practice and variability. Motor skill consolidation typically unfolds over days to weeks; durable transfer to competition may take months and depends on dose,specificity,and practice quality.

16. Can structured drills improve on-course performance (strokes gained)?

Answer: Theoretically yes-if drills are transferable, representative, and targeted at weak performance domains. Empirical confirmation requires RCTs or longitudinal studies linking practice interventions to strokes-gained metrics. Coaches should interpret improvements cautiously and verify with on-course data.

17. What are ethical and practical considerations in research with golfers?

Answer: Ensure informed consent, account for competitive schedules, minimize injury risk via warm-up and load management, and consider ecological validity versus experimental control. Use transparent reporting of methods, pre-registered hypotheses, and appropriate statistical techniques.

18. What gaps exist in the current evidence base?

Answer: Limited RCTs comparing structured, evidence-based protocols to standard coaching practices; insufficient long-term retention and on-course transfer studies; need for larger samples, especially across skill levels; and a paucity of integrative studies combining biomechanics, cognitive demands, and psychophysiological stressors.

19. What future research directions would yield the most practical impact?

Answer: Large-scale RCTs with ecologically valid transfer measures (strokes gained), mechanistic studies linking specific biomechanical changes to performance outcomes, individualized dosing studies to optimize practice volume, and longitudinal interventions across competitive seasons. Research into effective ways to scale technology-assisted feedback in field settings is also needed.

20. How should coaches translate the evidence into everyday practice?

Answer: Adopt a principled approach: assess athlete needs, design drills aligned with motor-learning and biomechanical evidence, integrate variability and interleaving, schedule distributed sessions with progressive challenges, use objective measurement judiciously, reduce feedback dependency over time, and evaluate retention and on-course transfer to iterate program design.

If you would like, I can (a) generate a printable drill program informed by these principles for a specific skill (e.g., approach shots, putting), (b) propose a research study protocol to test a particular structured drill, or (c) condense the Q&A into a short practitioner checklist. Which would you prefer?

outro – Structured Golf Drills: Evidence-Based Practice Methods

the evidence reviewed herein indicates that deliberately structured practice-characterized by well-defined objectives, systematically varied task constraints, targeted feedback, and progressive complexity-consistently enhances technical proficiency and shot consistency in golfers more effectively than unstructured repetition. Biomechanical analyses and motor-learning studies converge on several practical design principles: incorporate variability to promote adaptable movement solutions, employ contextual interference to strengthen retention and transfer, schedule practice according to spacing and dose-response considerations, and integrate representative task design to preserve ecological validity. The judicious use of objective measurement (e.g., launch-monitor metrics, kinematic analysis) further enables precise monitoring of skill change and individualized calibration of practice prescriptions.

For practitioners, these findings recommend a shift from volume-oriented, prescriptive repetition toward tailored, evidence-aligned practice programs that prioritize transfer to on-course contexts. Coaches should individualize drill selection and progression based on each golfer’s technical profile and learning rate, embed performance-relevant constraints within drills, and combine immediate, specific feedback with opportunities for self-regulation and error-based learning. Where feasible, supplement traditional coaching with technology-enabled assessment to guide decision-making and quantify outcomes.

Notwithstanding these positive trends, the extant literature contains methodological limitations-heterogeneous intervention definitions, small sample sizes, short follow-up intervals, and limited randomized controlled trials-that constrain the generalizability and causal interpretation of some results. Future research should emphasize well-powered, longitudinal designs, standardized reporting of drill parameters and outcome metrics, and investigations into optimal dosing, age- and skill-level moderators, and the mechanisms mediating transfer from practice to competitive performance.

Ultimately, when grounded in contemporary motor-learning theory and informed by biomechanical measurement, structured golf drills offer a pragmatic pathway to more efficient and transferable skill acquisition.Coaches, practitioners, and researchers are encouraged to adopt these evidence-based frameworks while continuing to evaluate and refine practice methods through rigorous, applied inquiry.

Alternate outro – “Structured” (planner/web app)

If the subject refers instead to the digital planner “Structured,” recent product developments (notably the launch of Structured Web and enhanced cross‑device sync) illustrate a drive toward greater accessibility and integrative task management. From an evidence-based perspective, continued evaluation of the planner’s effects on time-management behaviors, adherence, and productivity outcomes is warranted. Practitioners and researchers should collaborate to assess usability, longitudinal adoption, and efficacy across populations, informing iterative design improvements that align tool capabilities with empirically supported strategies for self‑regulation and goal attainment.