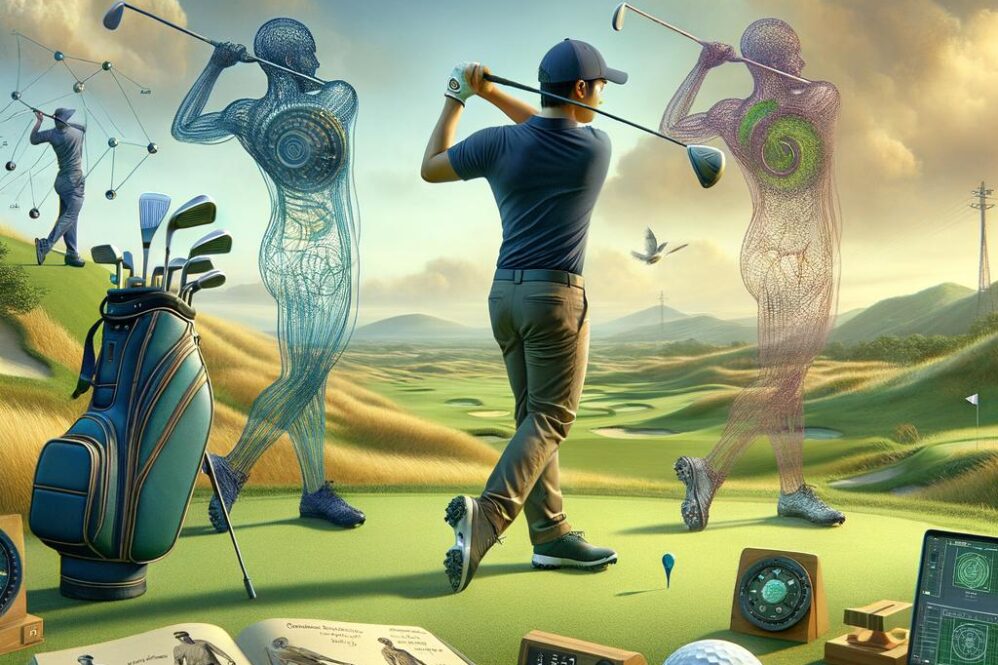

Cognitive processes-broadly defined as the mental activities involved in thinking, reasoning, and remembering (Cambridge dictionary; Merriam‑Webster)-play a central role in the acquisition and refinement of complex motor skills. In golf, where millimeter‑level adjustments and temporal precision determine performance outcomes, intentional manipulation of practice parameters can create conditions that enhance sensorimotor learning. Slow‑motion swing practice, which exaggerates temporal and kinematic features of the stroke, is increasingly advocated not only for biomechanical inspection but also for its potential to engage attention, working memory, and error‑based learning mechanisms more effectively than full‑speed repetition.

This article synthesizes theoretical perspectives and empirical findings linking slowed practice to cognitive enhancements relevant to golf performance.Mechanistically, slow‑motion repetition may increase conscious access to proprioceptive and kinesthetic cues, facilitate chunking of movement elements, and amplify sensory prediction errors that drive neural plasticity. These cognitive effects-improved attentional control, refined motor planning, and strengthened perceptual‑motor representations-are discussed in relation to practical coaching strategies and training design. By integrating definitions and frameworks from cognitive science with applied motor‑learning literature, the following analysis aims to clarify when and how slow‑motion swing practice can be implemented to optimize both learning and on‑course execution.

Theoretical Foundations of Slow Motion Practice and Motor Learning principles

In motor science,the term theoretical denotes abstract models and hypotheses that guide empirical investigation-an orientation that emphasizes explanation over mere description.Slow-motion swing practice can be situated within this theoretical frame as an experimental manipulation that makes internal control strategies observable and testable. By deliberately reducing movement speed, practitioners and researchers can isolate variables such as temporal sequencing, joint coordination, and sensory feedback without conflating them with high-velocity noise. This framing aligns practice design with the broader goal of converting theoretical constructs into measurable behavioral change.

Core motor-learning constructs explain why slowed execution is informative. Slow practice amplifies the role of internal models and sensory prediction, allowing golfers to refine feedforward commands while concurrently receiving clearer feedback for error correction. It also supports the refinement of hierarchical motor programs, enabling the reorganization of chunked subunits of the swing. Key mechanisms include:

- Attenuated sensorimotor noise: lower speed reduces measurement uncertainty in proprioceptive and visual signals.

- Enhanced error attribution: clearer mapping between intended and actual outcomes improves error-based learning.

- Temporal reweighting: increased time for processing supports the development of predictive timing.

Cognitively, slow-motion practice creates conditions favorable to both explicit hypothesis testing and eventual implicit consolidation. With reduced temporal pressure,athletes can allocate working memory to observe kinematic contingencies,test corrective strategies,and form declarative rules that later transfer into procedural representations. This progression-from conscious strategy to automaticity-is supported by neuroplastic processes during offline consolidation, where slowed practice episodes may yield richer encoding and more robust memory traces for complex coordinated actions.

Below is a concise mapping of theoretical constructs to empirically expected outcomes, followed by design implications for training programs.

| Theoretical Construct | Expected Outcome |

|---|---|

| Internal Models | Improved feedforward accuracy |

| Error-Based Learning | Faster correction of systematic biases |

| Chunking / Motor Programs | Reorganized sequencing of swing subunits |

| Attentional Allocation | Enhanced awareness of kinematic cues |

- Practical implication: use slow-motion trials interleaved with normal-speed repetitions to promote transfer.

- Dosage proposal: short, frequent slowed practice with focused feedback optimizes consolidation.

Enhancing Kinesthetic Awareness Through Deliberate Slow Motion Swing Repetition

Deliberately practicing the swing at markedly reduced speed facilitates measurable improvements in proprioceptive discrimination and sensorimotor integration. Neurophysiologically, slow, repetitive movement increases the fidelity of afferent feedback to somatosensory cortices and the cerebellum, permitting finer recalibration of joint-position sense and intersegmental timing. Such practice promotes the formation of richer internal models of the swing action, enabling the golfer to detect subtle deviations from desired kinematics that would or else be masked at full velocity. Enhanced body awareness is therefore not an epiphenomenon of slow practice but a predictable consequence of concentrated sensory sampling.

At the behavioral level, the method imposes a controlled reduction in temporal complexity that magnifies the perceptual salience of critical cues. Focusing attention on these cues during repetition accelerates motor learning by strengthening the mapping between sensory input and corrective motor output. Practically, golfers should attend to a small set of somatic markers to maximize returns from each repetition, for example:

- Foot pressure distribution throughout the weight shift

- Pelvic rotation timing relative to upper-torso motion

- Club-face awareness through the swing arc

- Rhythmic breathing to stabilize attentional resources

to operationalize this approach within a practice session, brief, frequent blocks of intentional slow repetitions are most effective. The following concise protocol illustrates a pragmatic session structure for improving somatosensory acuity and motor sequencing:

| Block | Duration | Primary Focus |

|---|---|---|

| warm-up (slow swings) | 5 minutes | Balance & pressure |

| Targeted repetition | 3 × 10 reps | Sequencing & face control |

| Reflection | 3 minutes | Verbalize sensations |

Empirical and theoretical evidence suggests that gains in somatosensory precision translate into improved error detection and faster corrective adjustments when returning to full-speed swings. The deliberate, mindful repetition cultivates cognitive capacities-sustained attention, working memory for sensory sequences, and metacognitive monitoring-that underpin more consistent performance. Coaches should therefore integrate slow-motion blocks not as mere technique work but as targeted cognitive-sensorimotor training; short, high-quality sessions emphasizing specific somatic cues yield disproportionate improvements in transfer and retention.

Neural Mechanisms Underpinning Precision and Error Correction During Slow Motion Practice

Slow, deliberate rehearsal of the golf swing amplifies the temporal and spatial resolution of incoming sensory signals, thereby strengthening the brain’s capacity to compare predicted and actual outcomes. This process relies on internal or forward models that generate predictions about limb trajectories and club-head dynamics; discrepancies between prediction and sensation produce a prediction error signal that drives corrective updates. Neuroanatomically, the cerebellum and posterior parietal cortex act as key comparators and error encoders, detecting minute mismatches during slow-motion practice that might potentially be missed during full-speed swings. As an inevitable result, slow practice increases the salience of sensory prediction errors and facilitates precise recalibration of motor commands.

The prolonged temporal window afforded by slow practice also shifts the balance between automatic and controlled processing,engaging prefrontal and premotor networks for conscious refinement of movement plans. Regions such as the primary motor cortex (M1), premotor cortex, and basal ganglia form recurrent loops that translate corrected plans into refined motor programs; simultaneous engagement of the prefrontal cortex supports attentional allocation and working memory for sequence-specific adjustments. Mechanistically, repetitive slow practice promotes synaptic plasticity (e.g., long-term potentiation-like changes) within these circuits, consolidating error-corrected patterns into more stable motor engrams. Empirical benefits therefore arise from an interplay between deliberate cognitive control and sensorimotor plasticity.

functional contributions of principal substrates during slow-motion training:

- Cerebellum: encodes prediction errors; refines timing and coordination.

- Posterior parietal cortex: integrates multisensory feedback for limb-state estimation.

- Prefrontal and premotor areas: sustain attention and transform corrective strategies into new motor plans.

- Basal ganglia: modulate selection and reinforcement of corrected movement variants.

For practitioners and researchers,these neural dynamics imply that slow-motion practice serves not merely as a biomechanical drill but as a targeted cognitive intervention: it magnifies error signals,enables explicit strategy evaluation,and promotes experience-dependent plasticity that later supports automatic execution. Monitoring modalities that index prediction error magnitude (e.g., kinematic deviations, proprioceptive mismatch) can be especially informative when designing practice schedules. Ultimately, integrating slow-motion rehearsal with graded increases in speed leverages both the brain’s error-correction machinery and consolidation processes to optimize precision and reliable performance on the course.

| Region | Primary contribution during slow practice |

|---|---|

| Cerebellum | High-fidelity error encoding and timing correction |

| Posterior parietal cortex | Multisensory integration for state estimation |

| Prefrontal / Premotor | Conscious strategy testing and motor plan refinement |

Translating Cognitive Gains Into On Course Performance Through Progressive Tempo Reintegration

Slow-motion repetition cultivates an explicit,highly detailed internal model of the swing that interfaces directly with cognitive processes such as perception,sequencing and judgment. As defined by Britannica, cognition encompasses the states and processes involved in knowing-perceiving and making judgments about sensory input-and slow, deliberate movement amplifies those processes by expanding the temporal window for error detection and correction. The resulting enhancements in attentional focus and motor portrayal create a substrate on which faster, more automatic performance can later be reconstructed.

A structured, graded reintroduction of tempo preserves these cognitive gains while encouraging efficient motor automation.Progression should be principled and empirically informed: begin with isolated component fidelity,then layer temporal compression and greater contextual complexity. key instructional emphases include maintaining perceptual anchors, preserving intersegmental sequencing, and controlling arousal to avoid premature reversion to bad habits.

- Isolated segments: reproduce the slow-motion pattern for critical swing windows (e.g.,takeaway,transition).

- Partial-speed chaining: rejoin adjacent segments at moderated tempo to test sequencing fidelity.

- Rhythmic scaling: incrementally compress timing while monitoring kinematic and attentional markers.

- Contextual stressors: introduce variability and pressure to assess transfer to performance demands.

To operationalize transfer, coaches and players should monitor a handful of cognitive and behavioral indicators and adapt tempo increments on that basis. The table below summarizes concise, actionable pairings of cognitive marker, representative practice cue and the corresponding on-course outcome to expect as tempo is restored.

| Marker | Practice Cue | On‑Course Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| Perceptual acuity | Visual-fixation + slow swing | Cleaner alignment to target |

| Sequencing accuracy | Segmental chaining at 70% tempo | Consistent contact under pressure |

| working memory consolidation | Dual-task rehearsal | Faster recovery after error |

Measurement and retention checks are essential to ensure cognitive gains persist when speed returns. Employ objective metrics (clubhead consistency, dispersion), contextual probes (simulated pressure holes), and delayed retention tests (repeat after 48-72 hours). Coaches should emphasize deliberate variability and mental rehearsal to maintain the explicit-to-implicit continuum: use short, frequent tempo-integration sessions, monitor for choking signs, and only advance tempo when perceptual and sequencing markers are stable. Such a scaffolded approach secures the transfer from deliberate, slow practice to robust on-course performance.

Structured Slow Motion Drills and Periodized Protocols for Skill Acquisition and Retention

Slow, deliberately paced swing rehearsals operate as a principled scaffold for motor learning by amplifying perceptual information and supporting error-detection processes that are or else masked at full speed. Empirical motor-control frameworks suggest that reduced temporal constraints increase the fidelity of proprioceptive and visual feedback, enabling learners to sample state-dependent contingencies and form richer sensorimotor mappings. In practice, this produces more accurate internal models and enhances the conversion of declarative task knowledge into robust procedural representations.

To maximize cognitive gains, drills must be structured around explicit objectives and measurable progression. Emphasize **tempo control**, **segmental awareness**, and **attentional focus shifts** (e.g., from global rhythm to wrist release timing) across micro-cycles of practice. Combine augmented feedback (video, auditory metronome cues) with intermittent blocked-to-random practice transitions; this preserves the stability benefits of repetition while introducing variability necessary for transfer. Objective logging of temporal metrics (swing duration, pause intervals) is recommended to quantify adaptation and guide load adjustments.

- Micro-slow drills: 6-8 second full-swing replication emphasizing coordination points.

- Segmental isolation: slow backswing only, slow transition only, slow follow-through only (reintegrate progressively).

- Perception-action coupling: slow swing with variable target constraints to force re-mapping to different contexts.

- Feedback layering: immediate kinematic cue, delayed reflective video review, and external focus reorientation.

Longitudinally, adopt a periodized protocol that phases slow-motion emphasis into acquisition, consolidation, and transfer blocks to optimize retention.Early phases prioritize high-repetition, low-speed rehearsal to encode stable movement solutions; mid-phases introduce controlled increases in velocity and contextual variability to promote generalization; final phases stress full-speed integration and competitive simulation. Complement these phases with spaced practice schedules, scheduled rest and sleep windows for offline consolidation, and periodic reassessment to ensure retention and adaptability.

| Phase | Primary Focus | Typical Duration |

|---|---|---|

| Acquisition | Sensorimotor encoding, tempo mastery | 1-3 weeks |

| Consolidation | Variability, error-tolerant mapping | 2-6 weeks |

| Transfer | Speed integration, contextual adaptability | 1-4 weeks |

| Maintenance | Retention drills, periodic assessment | Ongoing |

Measuring Progress with Objective Metrics and Assessment Strategies for Slow Motion Training

Objective measurement transforms slow-motion rehearsal from a subjective routine into a reproducible training modality that targets both motor and cognitive adaptation. By operationalizing changes in tempo, joint sequencing, and attentional control, practitioners can quantify improvements in precision and decision-making. Key metrics commonly tracked include:

- Temporal consistency – duration of backswing and follow-through (milliseconds).

- Kinematic sequencing – order and timing of segment rotations (shoulder → hips → hands).

- Movement variability – trial-to-trial standard deviation as an index of stability.

- Perceptual-cognitive indices – reaction time, sustained attention, and working memory load.

Assessment strategies should pair biomechanical instrumentation with validated cognitive measures so the practitioner captures the full scope of adaptation.Start with a baseline battery: high-speed video for stroke-phase analysis, wearable IMUs or radar for tempo and angular velocity, and short computerized tests for attention and reaction time (cognitive here refers to processes related to thinking and conscious mental operations). Employ repeated, short-block testing (e.g., 6-10 slow-motion swings per block) to reduce fatigue effects and to compute reliable averages and variability estimates. Integrate blinded retention tests at 1-2 week intervals to assess transfer from deliberate slow practice to natural-speed execution.

| Metric | Tool | Frequency | sample Target |

|---|---|---|---|

| Backswing duration | High-speed video / IMU | Weekly | ±5% of baseline |

| Segment sequencing | Motion-capture/IMU | Biweekly | Consistent proximal-to-distal pattern |

| Trial variability | Statistical summary | Per session | Reduction trend over 4 sessions |

| Reaction time | Simple RT test | Monthly | Improved or stable |

Interpreting data requires pre-defined progression rules and an recognition that cognitive and motor gains may follow different timelines.Use moving averages to smooth session-to-session noise and calculate effect sizes rather than relying solely on p-values for practical change. Practical decision rules include:

- If temporal consistency improves but variability remains high → emphasize repetition with attenuated complexity.

- If kinematic sequencing stabilizes but transfer to full-speed swing is poor → introduce graded re-acceleration drills.

- If perceptual-cognitive scores decline → reduce cognitive load in sessions and reintroduce attentional cues progressively.

Practical Considerations and Safety Guidelines for Implementing Slow Motion Swing Practice in Coaching

Coaches should begin by conducting a brief pre-screening to identify musculoskeletal limitations, previous injuries, and current fatigue levels. Emphasize a progressive warm-up that includes dynamic mobility for the thoracic spine,hips,and shoulders; use low-load,high-control movements to prime neuromuscular pathways before introducing intentionally decelerated swings. Maintain an evidence-informed tempo: initial sessions can limit slow-motion practice to short series (e.g., 6-10 swings) to avoid overuse of small stabilizing muscles and to preserve movement quality throughout the training session. Individualization is essential-what constitutes “slow” should be anchored to each golfer’s motor control capacity rather than an arbitrary time target.

instructional progression must balance cognitive load and motor learning demands. Begin with external-focus cues and simplified movement targets, then layer complexity by increasing sequencing demands and reducing visual feedback. Suggested practical steps for session design:

- Phase 1: Guided slow-motion with tactile or verbal cues (3-5 minutes).

- Phase 2: Independent slow swings with alternating normal-speed attempts (2:1 ratio).

- Phase 3: Transfer drills incorporating full-speed execution under controlled constraints.

Monitoring and objective feedback are critical to link cognitive intent with observable outcomes. Use simple video capture at reduced frame rates or frame-by-frame review to highlight sequencing errors and temporal patterns; employ brief cognitive probes (e.g., asking the golfer to verbalize intended kinematic landmarks) to verify mental representation aligns with movement. Track session metrics such as perceived exertion, number of quality slow swings, and transfer success on brief full-speed trials; these metrics provide data for adjusting frequency and volume. Emphasize short, distributed practice bouts to facilitate consolidation and minimize attentional fatigue-particularly for novice learners.

Risk mitigation includes clear return-to-play criteria for athletes with prior upper-body or lumbar pathology and scheduled recovery strategies (soft-tissue work, mobility drills, and rest intervals). On-course integration should follow laboratory-style practice: once consistent kinematic markers are achieved in slow practice and during constrained full-speed trials, progressively reintroduce environmental variability (lie, wind, strategic targets) to evaluate cognitive adaptability. For documentation and communication with multidisciplinary teams, consider a concise training log template noting: goal, tempo, quality score, and transfer outcome; this supports safe progression and objective coaching decisions.

Q&A

1. Question: How is “cognitive” defined in the context of motor-skill practice such as slow-motion golf-swing training?

Answer: In this context, “cognitive” refers to the set of mental processes that support perception, attention, memory, decision-making and the conscious aspects of motor planning and monitoring. General lexical and encyclopedic definitions emphasize that cognitive processes are “connected with thinking or conscious mental processes” and include perception, recognition, and reasoning (see Cambridge Dictionary; Britannica; Wikipedia) [1][2][4]. When applied to sport,cognition describes the mental operations that encode sensory information,plan and adjust movement,and consolidate motor memory.

2. Question: What is slow‑motion golf‑swing practice?

Answer: Slow‑motion golf‑swing practice is a deliberate training technique in which the golfer executes swing components or the entire swing at substantially reduced velocity compared with normal play. The aim is to increase temporal and kinesthetic awareness of body segments, to examine sequencing and timing, and to permit focused attentional processing of movement errors and desired biomechanics.

3. Question: Which cognitive processes are most engaged during slow‑motion swing practice?

Answer: Slow‑motion practice primarily engages: (a) perceptual processes (visual and proprioceptive sensing of limb position and movement), (b) attention and working memory (maintaining instructions, monitoring movement phases), (c) error detection and correction (comparison of intended vs. actual kinematics), and (d) memory encoding/consolidation (storing refined motor plans). Executive functions (planning and inhibitory control) are also active as the golfer deliberately modulates timing and coordination.4. Question: Through what mechanisms does slow‑motion practice produce cognitive benefits relevant to golf performance?

Answer: Principal mechanisms include:

– Enhanced proprioceptive acuity: Slower movement increases the signal-to-noise ratio for kinesthetic feedback, improving internal models of limb position and timing.

– Improved error detection and explicit knowledge: Slower execution exposes discrete phases and errors that might potentially be invisible at full speed, supporting verbalizable corrections.

– Strengthened motor planning and sequencing: Prolonged phase durations help the nervous system refine intersegmental coordination and timing relationships.

- Facilitated consolidation: Repeated, deliberately-attended slow repetitions may produce stronger initial encoding of desired movement patterns, which can then be consolidated into longer-term motor memory.- Transfer via chunking and motor imagery: Slower practice supports cognitive chunking of complex sequences and increases the effectiveness of imagery-based rehearsal.

5. Question: What does motor‑learning theory suggest about the efficacy of slow‑motion practice?

Answer: Motor‑learning theory indicates that slowed, attended practice can accelerate acquisition of explicit skills by increasing error salience and permitting conscious strategy adjustments. However,theory also cautions that skills dependent on automatic,high‑speed sensorimotor coupling require practice under near‑performance conditions for optimal transfer. Thus, slow‑motion practice is most effective as a component of a broader practice schedule (e.g., initial technique refinement followed by progressive speed and contextual variability).

6. Question: What empirical evidence supports cognitive benefits of slow‑motion or reduced‑speed practice (generally and in sport)?

Answer: Direct experimental studies specific to slow‑motion golf swings are limited. Broader motor‑learning literature supports that slowed or segmented practice improves proprioceptive awareness, explicit knowledge, and early-stage error correction. Evidence from related domains (e.g., rehabilitation, musical instrument training, other sports) demonstrates benefits for accuracy and technique learning when slow, focused repetitions are combined with feedback. Nevertheless, high‑quality, sport‑specific trials are needed to quantify effect sizes and optimal dosing for golf.

7. Question: What cognitive trade‑offs or limitations should coaches and golfers be aware of?

answer: Key trade‑offs include:

– Over‑reliance on explicit control: Excessive slow,conscious control can impede automatization and speed of response under pressure.- Limited transfer if not integrated with full‑speed practice: Motor patterns learned only at slow speeds may not scale linearly to high velocities.

– Cognitive load: Slow, highly attended practice increases working‑memory demands and may be fatiguing over long sessions.Coaches should thus scaffold slow practice with progressive speed,implicit‑learning strategies,and variability to promote robust transfer.

8. Question: How should slow‑motion swing practice be structured within a periodized training plan?

Answer: Suggested structure:

– Initial phase (Technique analysis): Use short bouts (5-10 minutes) of slow‑motion practice focused on one or two specific elements (e.g.,wrist hinge,weight shift) with external video or coach feedback.

– Integration phase (Speed progression): Gradually increase tempo across sessions, interleaving slow reps with medium and full‑speed repetitions (e.g., 3 slow : 1 medium : 1 full).

– Consolidation phase (Contextual practice): Introduce variability (different lies,club types,pressure conditions) and incorporate implicit cues to reduce conscious control.

Session frequency: 2-4 short (15-30 minute) focused sessions per week is common for skill refinement; exact dosage should be individualized.

9. Question: What instructions and attentional focus are optimal during slow‑motion practice?

Answer: Use concise, externalized cues when possible (e.g., “create clubhead speed through hip rotation” framed as an outcome) for later stages, but allow brief internal attention during early slow reps to feel specific joint actions. Combine slow practice with guided feedback (video, mirror, coach) to anchor perception to objective outcomes. Gradually shift to external focus and outcome-based cues as tempo increases to encourage automaticity.

10. Question: Which golfer populations stand to benefit most from slow‑motion practice?

Answer: Beneficial for:

– Novices learning correct sequencing and basic mechanics.

– Intermediate players correcting specific technical faults where kinesthetic awareness is low.

- Injured or rehabilitating golfers who must re‑learn components of the swing at safe speeds.

Elite players may use targeted slow‑motion drills for fine technical adjustments but should limit overall exposure to preserve automaticity.11. Question: How should practitioners measure cognitive and performance changes resulting from slow‑motion practice?

Answer: Recommended outcome measures:

– Perceptual/proprioceptive: joint position sense tests, subjective kinesthetic awareness scales.

– Cognitive: attentional load (dual‑task tests), working‑memory measures, explicit knowledge questionnaires.

– Performance/transfer: accuracy and dispersion of full‑speed shots, clubhead speed, kinematic sequencing metrics (motion capture), retention tests (delayed performance), and transfer tests under competitive pressure. Pre-post designs with retention and transfer phases are critical.

12. Question: How can coaches minimize the risk that slow practice reduces high‑speed performance?

Answer: Mitigation strategies:

– Blend slow practice with speed‑specific and variability practice within the same sessions.

– Use progressive overload of tempo – incrementally approach full speed across sessions.

– Incorporate contextual interference (varying tasks) and implicit learning techniques (analogy cues) to foster automaticity.

– Periodically test performance under simulated pressure to ensure robustness.

13. Question: what practical drills exemplify effective slow‑motion practice for golf?

Answer: Examples:

– Segmental sequencing drill: Slow full swing with pause at key checkpoints (top of backswing,impact plane) while coach/video feedback is provided.

– Kinematic cueing drill: Execute the downswing at ~50% speed focusing on hip rotation timing, then instantly perform a full‑speed hit.

– Mirror/imagery pairing: slow swing while verbally describing felt sensations,then visualize full‑speed execution before hitting.

Each drill should have specific, measurable objectives and limited repetitions to avoid fatigue.

14. Question: What are productive directions for future research on cognitive benefits of slow‑motion golf practice?

Answer: Priority areas:

– Randomized controlled trials comparing slow‑motion protocols vs. traditional and mixed‑tempo practice on retention and transfer in golf.

- Neurophysiological studies (EEG, fMRI) to characterize changes in sensorimotor representations and attentional networks.

– Dose-response research to define optimal tempo, repetition counts, and session frequency.

– Studies of how individual differences (age, prior experience, working‑memory capacity) moderate benefits.

15. Question: Summary – when and why should slow‑motion swing practice be used?

Answer: Slow‑motion practice is a valuable, evidence‑informed tool for enhancing sensory awareness, error detection, and explicit technique refinement. It is particularly useful in early learning, targeted technical correction, and rehabilitation. To maximize cognitive and performance gains, slow practice should be employed strategically-brief, targeted, and progressively integrated with speed and variability training to promote automatization and transfer to competitive play.

References and further reading: for authoritative definitions of cognition and its components, see Cambridge Dictionary (cognitive) [1], Britannica (cognition) [4], and general overviews of cognitive processes (Wikipedia) [2].These resources help frame the mental processes engaged by slow‑motion motor practice.

In sum, slow‑motion swing practice represents a purposeful intervention that engages core cognitive processes - including perception, attention, working and procedural memory, and error‑based learning – to support the refinement of motor skill in golf. By decelerating the movement, practitioners are afforded increased prospect to detect and correct biomechanical errors, to enhance proprioceptive awareness, and to consolidate more stable motor programs. These cognitive mechanisms are consistent with contemporary conceptions of cognition as the suite of mental processes involved in learning, remembering, and using knowledge.For coaches and practitioners,the evidence reviewed suggests that slow‑motion rehearsal can be a valuable component of a broader training regimen when applied strategically. Best practice recommendations include using slow‑motion drills to isolate and internalize specific technique elements, pairing them with augmented feedback (video, verbal cueing, or kinesthetic guidance), and then progressively reintegrating movements at competition speed and under variable contexts to promote transfer. Attention to individual differences (e.g., experience level, injury history, cognitive load tolerance) will optimize outcomes and reduce the risk of maladaptive motor patterns.

Future research should more precisely delineate the neural and behavioural mechanisms by which decelerated practice facilitates learning, examine dose-response relationships, and evaluate long‑term transfer to on‑course performance and pressure situations across age groups. Until such data are available, slow‑motion swing practice should be considered an empirically grounded, cognitively informed adjunct to traditional training – one that leverages deliberate perception and memory processes to enhance precision, consistency, and ultimately, performance.

The Cognitive Benefits of Slow-Motion Golf Swing Practice

What slow-motion swing practice is – and why cognition matters

slow-motion swing practice is a intentional training method where golfers perform the full golf swing or parts of it at a reduced speed to emphasize feeling, timing, and movement quality. This approach targets not just the physical mechanics of the golf swing, but also the cognitive processes that govern learning, attention, and motor control.

The word “cognitive” refers to the mental processes involved in knowing, perceiving, remembering and learning (see Dictionary.com and Cambridge Dictionary). In sport science and psychology this encompasses attention, working memory, motor planning and perception – all critical for consistent on-course performance (Verywell Mind; Britannica).

How slow-motion swing training improves cognitive processes

Slow-motion practice enhances several specific cognitive functions that transfer directly to better golf technique and more reliable performance:

- Heightened attention and awareness: Slowing down forces you to notice subtle positions, grip, and balance – improving situational awareness during the swing.

- Improved motor planning: The brain refines the sequence of muscle activations required to produce an effective swing, strengthening neural pathways for the full-speed motion.

- Stronger proprioception and body schema: Slow reps let you map where each joint and segment is through the swing,improving proprioceptive feedback and position sense.

- better error detection and correction: With more time to perceive each phase of the swing, golfers can identify faults and make intentional corrections in real time.

- Consolidation of muscle memory: Repeated slow, accurate movements create robust motor engrams that are executed more reliably when speed is increased.

- Reduced cognitive load under pressure: Training slowly with explicit focus helps chunk complex swing sequences into automated components, freeing up working memory on the course.

evidence and theory: why slow is smart

Motor learning and cognitive psychology identify key mechanisms that make slow-motion practice effective. cognition involves perception, recognition and reasoning; practice that emphasizes perception (position, feel, timing) helps learners encode movements more richly (Britannica; Verywell Mind). Slower movement increases sensory feedback per repetition, which boosts error-based learning and reinforcement of correct movement patterns.

From a biomechanics perspective, slow movements allow precise control of joint sequencing and tempo; from a cognitive perspective, they increase attention to sensory inputs and internal models that the brain uses to predict and plan movement.

Practical benefits for golfers: what you’ll gain

- Consistent ball-striking: Better motor planning and proprioception lead to more consistent clubface control at impact.

- Improved swing tempo and rhythm: Slow practice helps you internalize a smooth tempo that scales up to full speed.

- Sharper short game touch: Putting, chipping and pitch shots require fine motor control – skills that benefit directly from slow, focused practice.

- Faster learning of technical changes: When a coach asks for a new movement pattern, slow reps accelerate understanding and retention.

- Better shot selection under pressure: Reducing mental noise through practiced movement patterns makes course decisions easier to execute.

Slow-motion drills and exercises (with cognitive focus)

Below are drills designed to target both the physical mechanics and the cognitive processes behind a repeatable swing.

| Drill | Duration / Reps | Cognitive Focus |

|---|---|---|

| 3-Second Backswing / 3-Second Downswing | 8-12 reps | Sequencing & attention to transition |

| Pause at the Top (2-3 seconds) | 6-10 reps | Proprioception & error detection |

| Mirror Feedback Slow Swings | 10-15 reps | Visual self-correction |

| Imagery + Slow swing (mental rehearsal) | 5-10 imagery sets + 6 physical reps | Motor planning & neural priming |

Drill details and coaching cues

- 3-Second Backswing / 3-Second Downswing: Count evenly to three on the takeaway and three on the downswing. Focus on maintaining posture and a smooth transition through the top. This drill forces you to feel the kinetic sequence and how the hips, torso and arms coordinate.

- Pause at the Top: Pause briefly at the top of the swing. Use that pause to check clubface angle, spine tilt, and weight distribution. Pausing enhances error detection and the ability to correct before accelerating.

- Mirror Feedback: Stand in front of a mirror and make very slow swings while comparing your positions to a reference (coach demo or video). Visual input accelerates the brain’s ability to correct and encode correct movement patterns.

- imagery + Slow Swing: Combine mental rehearsal with slow physical reps. Visualize a prosperous shot,than perform a slow,focused swing. Imagery primes neural circuits for the movement,boosting motor learning.

How to structure a slow-motion practice session

Below is a sample 45-60 minute session that blends cognitive focus with physical repetition to maximize transfer to full-speed shots.

- Warm-up (5-10 min): Dynamic mobility and short, gentle swings to wake up sensory systems.

- Focused slow-swing block (15-20 min): Choose 2-3 slow-motion drills and perform 8-12 quality reps per drill, with rest between sets. Use mirror or video and external cues to keep attention sharp.

- Integrated tempo work (10-15 min): Gradually increase tempo while maintaining the learned positions. Use a metronome or 1-2-1 count to scale speed without losing sequence.

- Short-game slow practice (10 min): Slow putt and chip strokes to develop feel and fine motor control.

- Reflection and notes (5 min): Write one to three observations about feel, positions, or adjustments for next session.

Coaching tips: how teachers use slow-motion training

Coaches often use slow-motion practice to:

- break down the swing into manageable chunks for new motor learning.

- Provide immediate feedback and cueing when the golfer has more time to perceive movement.

- Integrate video analysis by matching slow positions to ideal frames.

- Use tempo training to create a durable rhythm that scales up to full speed.

when a PGA coach asks a student to slow down, the goal isn’t to play slow golf – it’s to improve the brain’s representation of the movement so the body executes it correctly at speed.

Case studies and first-hand anecdotes (illustrative)

Case Study 1: Amateur golfer with inconsistent impact

- Problem: Frequent toe and heel strikes; variable ball flight.

- Intervention: Four weeks of twice-weekly slow-swing training (pause-at-top + mirror feedback).

- Result: Reduced dispersion due to improved clubface awareness and a more repeatable downswing sequence.

Case Study 2: Senior golfer seeking better short game touch

- Problem: Lack of feel from 20-40 yards; speed over-control issues.

- Intervention: Slow-paced pitching practice coupled with imagery routines and tempo metronome work.

- Result: Improved distance control and fewer fat/thin shots due to enhanced proprioceptive mapping.

These examples show how cognitive-focused, slow practice produces measurable, lasting changes in motor control and on-course performance.

Common mistakes and how to avoid them

- Doing slow practice without attention: Slow reps must be mentally engaged – mindless slow swinging offers limited benefit. Use cues, mirror, or video to stay focused.

- Overdoing volume: Quality over quantity. Short, highly focused blocks are better for cognitive encoding than long, unfocused sessions.

- Not integrating speed scaling: Always follow slow practice with staged increases in tempo so the brain can adapt the learned pattern to full-speed performance.

- Ignoring posture or fitness constraints: If pain or mobility limits proper positions,consult a coach or health professional before forcing slow motion patterns.

How to measure progress

Track both objective and subjective indicators to measure betterment:

- Objective: Ball dispersion, impact location on the clubface, shot-tracking metrics (carry, dispersion), putt length control.

- Subjective: Confidence in tempo, ease of reproducing positions, clarity of feel and reduced need for conscious thinking on the course.

- Practice log: Note exact drills, reps, tempo counts, and one key observation each session.

putting cognitive science into your practice plan

Remember: cognition is about how you process information during learning (see Cambridge Dictionary and Verywell Mind for deeper definitions). Slow-motion swing practice enriches the information available to your brain during training – more sensory feedback,clearer error signals,and stronger motor planning. When combined with deliberate practice, feedback, and progressive tempo work, slow practice becomes a high-value tool for any golfer seeking better precision, consistency and confidence.

Swift checklist before your next slow practice session

- Set a clear objective for the session (e.g., improve transition, feel wrist hinge).

- Limit distractions: phone off, focused time block (25-45 minutes).

- Use a mirror or smartphone video for external feedback.

- Start very slow, then scale speed in controlled phases.

- Record one or two improvements and one next-step action.

Use slow-motion swing practice not as an end, but as a cognitive rehearsal strategy that strengthens the neural blueprint for a better golf swing – leading to more precise shots, reliable tempo, and confidence when the course pressure rises.