The sport commonly identified as golf, with documented play dating to fifteenth-century Scotland, provides a rich case study in how rules, physical landscapes, and social dynamics co-evolve to produce durable cultural institutions. This article examines three interrelated arenas of change: the formalization and international dissemination of rules and governance; the morphological and technological transformations of course design from medieval linkslands to twentieth- and twenty-first-century parkland, resort, and urban courses; and the shifting social meanings of the game as shaped by class, gender, race, professionalization, media, and commercial forces.Combining archival research on early club codes and regulatory bodies, architectural and environmental analyses of course evolution, and sociohistorical approaches to participation and portrayal, the study traces how adaptations in equipment, playing conventions, and landscape engineering have been both responses to and catalysts for broader societal change. Attention to continuity and innovation reveals that golf’s enduring traditions persist not as static relics but as negotiated practices that reconcile heritage with technological advancement, regulatory standardization, and demands for greater inclusivity and sustainability. by foregrounding the reciprocal relationships among rules, courses, and society, the article situates golf within wider debates on how sport mediates cultural identity, economic interests, and environmental stewardship.

Note: the brief web search results provided concern biological evolution and do not address the historical literature on golf; the foregoing synthesis is informed by established scholarship and primary-source traditions in the history of the sport.

Historical Foundations and the Codification of Play: Tracing Early Practices into Standardized Rules and Recommendations for Archival and Comparative Research

| Source Type | Primary Use |

|---|---|

| Club minute books | Procedural rules, membership disputes |

| local newspapers | Match conventions, public debates |

| Maps & plans | Course layout evolution |

| Trade catalogues | Equipment standards and diffusion |

Employ methodological triangulation-corroborating documentary, material, and visual evidence-to avoid overreliance on any single genre.

- Establishing comparative chronologies for clubs and courses across regions;

- Applying GIS to map course morphologies against land-use change;

- Integrating oral histories and photographic corpora to capture ephemeral practices.

Prioritize provenance and contextualization in evidence selection, and consider mixed-methods designs (textual coding, network analysis, and quantitative scoring of rule convergence) to reveal the mechanisms by which everyday play crystallized into the standardized laws that characterize modern golf.

The 18-Hole Convention and Course Metrics: Origins, institutional Adoption, and Guidance for Preserving Historical Integrity While Allowing Adaptive Layouts

Historical fixation on 18 holes emerged from pragmatic consolidation rather than a single prescriptive decree: the Old course at St Andrews and subsequent codifications gave steady form to a round composed of eighteen playing units, and the number itself carries broad symbolic and utilitarian resonance as an integer encountered across legal and social conventions. This numeric fixity shaped expectations for rounds,tournaments,and player stamina,producing a durable standard against which course architects and governing bodies measured length,par and pacing. Acknowledging the cultural and numerical prominence of 18 helps explain why deviations have been treated as exceptions rather than alternatives.

Institutional adoption translated into measurable course metrics-yardage bands, par allocations, and formally recognized rating systems-so that courses could be compared, handicaps computed, and championships administered. Modern metrics now routinely include:

- Course Rating (expected score for a scratch golfer),

- Slope Rating (relative difficulty for bogey golfers),

- Aggregate yardage and par (play length and nominal scoring target).

These quantifications were institutionalized by national and international bodies to protect competitive integrity while enabling architects to design within a transparent framework. Clear metric thresholds also facilitate cross-era comparisons, an important consideration for courses seeking to retain historical claim while meeting contemporary expectations.

Preserving historical integrity while permitting adaptive layouts requires principled guidance. Stewardship policies should prioritize reversible interventions, documentation of original design intent, and selective modernization that maintains character-defining features. Recommended practices include:

- Reversible changes (temporary tees, modular routing for events),

- Contextual modernization (irrigation and drainage upgrades sited to avoid altering sightlines),

- Layered documentation (archival plans, photographic records, and measured drawings retained for future restoration),

- Play-variant signaling (clearly signed choice tees or hole routings so the 18-hole tradition is respected when required).

This rubric balances respect for historical form with practical needs for accessibility, sustainability, and multi-use programming.

practical trade-offs can be summarized succinctly:

| Constraint | Adaptive option |

|---|---|

| Legacy routing | Seasonal alternate tees |

| Historic green locations | Micro-topography correction only |

| Length for modern equipment | Selective bunker repositioning |

Design decisions should explicitly record whether changes are intended to be permanent or reversible, and whether the 18‑hole layout is being preserved as a cultural artifact or adapted to new programmatic needs. By codifying such decisions and retaining the symbolic weight of the number 18 as both a performance standard and a cultural reference point, architects and stewards can reconcile historical integrity with adaptive, sustainable course evolution.

Evolution of Course Design and Landscape Architecture: Technical Innovations, Environmental Stewardship, and Policy Recommendations for Sustainable Course Planning

Over the past century design philosophy has migrated from rigid, penal forms toward a more nuanced, strategic aesthetic that privileges **choice architecture** over simple punishment. Advances in surveying and modelling – notably **LiDAR**, **GPS-based routing**, and high-resolution **3D terrain modelling** – have enabled architects to manipulate landform at unprecedented scales while preserving the illusion of naturalness. Concurrently, improvements in agronomy and **turfgrass selection** broadened maintenance regimes, permitting variety in fairway and green textures that change shot selection and tournament strategy. The technical synthesis of geomorphology, hydrology and materials science now informs decisions that once rested on intuition alone, allowing for repeatable, evidence-based design outcomes.

Contemporary landscape practice reframes golf facilities as multifunctional ecosystems where playability coexists with measurable ecological benefits. Embracing **water stewardship**, soil health and habitat connectivity reduces long-term maintenance costs and improves resilience to climatic variability. Core practices include:

- Water-efficient irrigation – microspray and soil-moisture feedback systems;

- Native riparian buffers – stabilizing banks and filtering runoff;

- Integrated pest management – threshold-based interventions over calendar spraying;

- Soil and carbon management – compost amendments and carbon sequestration plantings;

- Renewable energy integration – electrical fleets and solar-powered irrigation.

To translate technical and ecological advances into widespread practice, policy frameworks must couple regulation with incentives that reward stewardship.Recommended elements of an enabling policy suite include performance-based water and chemical use targets, expedited permitting for habitat restoration, grant funding for retrofit projects, and requirements for long-term environmental monitoring tied to public reporting. the following table summarizes pragmatic policy levers and illustrative outcomes:

| Policy Lever | Primary Objective | Illustrative Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| Performance targets | Reduce resource use | 20% lower irrigation demand |

| Restoration grants | Support habitat projects | increased pollinator corridors |

| Openness reporting | Enable accountability | Public scorecards |

Long-term viability depends on integrating governance, economics and adaptive management into the design lifecycle. Facilities should adopt **adaptive management** protocols with embedded monitoring to test design hypotheses, and use life-cycle cost analysis to evaluate trade-offs between capital earthworks and operational expenses. Digital tools – from sensor networks to a comprehensive **digital twin** of the landscape – enable scenario testing, stakeholder engagement and transparent reporting. By aligning technical innovation with ecological objectives and pragmatic policy,course planning can produce landscapes that are both strategically rich for play and demonstrably sustainable for future generations.

Club and Ball Technology Through the Centuries: Material Science, Performance Consequences, and Regulatory Strategies to reconcile Innovation with Competitive Fairness

Over two centuries of incremental innovation, club and ball construction has migrated from organic, hand-crafted materials to engineered composites and precision alloys. Early hickory shafts and persimmon heads gave way to steel, aluminum, titanium, and carbon-fiber, each substitution altering bending stiffness, mass distribution, and impact damping. Ball design followed a parallel trajectory: featheries and gutties evolved into rubber-core wound balls and, later, multilayer solid-cores with tailored mantle and cover constructions. These material transitions are best understood through the lens of material science metrics-young’s modulus, density, loss factor and fatigue resistance-which together determine energy transfer, durability, and feel at impact.

The performance consequences of these material choices are multi-dimensional and empirically measurable. Clubs with higher moment of inertia and optimized center-of-gravity position produce greater forgiveness and launch control; lighter, stiffer shafts change temporal sequencing and influence swing tempo. Modern multilayer balls decouple driver-distance from short-game spin characteristics, enabling greater overall carry without proportionate loss of greenside control. Such outcomes have quantifiable implications for shot dispersion, trajectory stability, and scoring distribution across different handicap cohorts-factors that complicate both competitive integrity and historical comparison.

- Ball velocity vs. spin: higher COR and optimized core construction increase initial speed but modern covers and mantle layers manage spin for approach shots.

- Club forgiveness vs. workability: increased MOI reduces dispersion but can diminish the player’s ability to intentionally shape shots.

- Shaft dynamics: material stiffness and taper profile alter release timing, affecting launch angle and spin rate.

Regulatory frameworks-primarily administered by the R&A and USGA-seek to reconcile technological progress with competitive fairness through measurable constraints and conformity testing. Instruments include maximum coefficient of restitution thresholds, limits on initial velocity, groove and face specifications, and standardized testing protocols using launch monitors and robot-strike rigs. Effective governance balances several principles: preserving the skill-based challenge of the game, ensuring safety and accessibility, and maintaining historical continuity for records and course design. policy options under discussion range from dynamic testing regimes and equipment “sunset” provisions to collaborative design standards that involve manufacturers, elite players, and governing bodies in iterative rule progress.

Governing Bodies, Professionalization, and Competitive Structures: How Institutions Shaped Modern Golf and Recommendations for Transparent, Accountable Governance

Formal institutions such as national unions and international councils transformed a diffuse set of local practices into a coherent rule system, producing the standardized lexicon and adjudicatory procedures that underpin contemporary play. Through codification, arbitration panels, and reciprocal recognition agreements, these organizations reduced regional variance and created a predictable legal and competitive habitat.The consolidation of rule-making authority also enabled the transfer of rulings across jurisdictions, aligning etiquette, measurement standards, and equipment definitions in ways that made intercontinental competition practicable and regulated technological change.

The professionalization of the sport recalibrated incentives across the ecosystem: tournament circuits,ranking systems,and commercial contracts directed resources toward elite performance while also shaping course architecture and maintenance regimes. Course designers responded to new performance baselines by adjusting hazard placement,length,and green complexity; equipment manufacturers pursued incremental gains within regulatory envelopes; and governing institutions iteratively modified parameters to preserve competitive balance. This dynamic produced both a higher-performance spectacle and persistent tensions between preservation of tradition and accommodation of innovation.

Institutional weaknesses have become visible where governance arrangements lack transparency, independent oversight, or broad stakeholder representation. Conflicts of interest, opaque rulemaking processes, and uneven disciplinary practices undermine legitimacy in both national federations and global bodies. To address these shortcomings, policy reforms should emphasize clear conflict-of-interest policies, published rationales for regulatory change, and accessible records of committee deliberations. such measures strengthen accountability without impeding the technical expertise necessary for rule development.

Practical governance mechanisms that preserve the sport’s integrity while promoting inclusivity can be summarized as follows:

- Independent review panels for financial and disciplinary matters to reduce capture and bias.

- Open consultation periods with transparent comment summaries to incorporate players, clubs, and manufacturers.

- Periodic impact assessments to evaluate how rule changes affect access,cost,and competitive parity.

| Mechanism | Primary Benefit |

|---|---|

| Independent Audit | Financial integrity |

| Open Rulemaking | Legitimacy and buy-in |

| Term Limits | Prevent institutional capture |

Social Contexts of Play and Access: Class, Race, Gender, and Amateurism with Prescriptive measures to Promote Inclusion and Broaden Participation

Economic stratification shapes patterns of participation as decisively as course design. The outlay required for green fees, coaching, equipment, and the informal social capital associated with private clubs produces durable barriers to entry; these barriers interact with wider public-policy frameworks (for example, institutions such as the Social Security Management emphasize universal access to social goods) to reveal a lacuna: golf has no equivalent public infrastructure to guarantee baseline access. Policy-oriented interventions should therefore reframe access as a matter of social provision rather than purely market allocation, and proponents must prioritize sliding-scale fees, municipal course investment, and scheduled community tee times to redress class-based exclusion.

| Barrier | Prescriptive Measure |

|---|---|

| Cost of play & equipment | Public rentals, equipment libraries, subsidized coaching |

| Club exclusivity | Community governance models, anti-discrimination covenants |

| Time poverty | Flexible tee scheduling, shorter-course formats |

Racial and gender disparities in access and representation require interventions that are both structural and cultural. empirical studies of participation suggest that representation at decision-making levels and visibility in media coverage correlate strongly with grassroots uptake. Practical measures include:

- Targeted outreach: youth programs in underrepresented neighborhoods and partnerships with schools;

- Institutional accountability: diversity benchmarks for tournament organizers and club boards;

- Facility design: accessible locker rooms, childcare at events, and inclusive signage and amenities.

These steps,framed by rigorous monitoring,will shift golf from a gatekept pastime toward a genuinely pluralistic sporting field.

The contemporary ideal of amateurism must be reconceived to support, rather than exclude, broader participation. Rather than romanticize exclusionary notions of “pure” amateur play, governing bodies should adopt tiered competitive pathways that preserve traditions while facilitating upward mobility: community leagues, city championships, and scholarship-linked performance tracks that bridge to elite amateur events. Financial support-microgrants, transparent sponsorship pools, and needs-based travel stipends-should be institutionalized so that talent is not filtered out by socioeconomic status. Moreover, codes of conduct and mentorship programs can mitigate opposed cultures that disproportionately deter women and racial minorities from sustained engagement.

Operationalizing inclusion requires measurable goals, sustained resourcing, and iterative evaluation. Key performance indicators should include participation rates disaggregated by class, race, and gender; retention rates across age cohorts; and the proportion of leadership roles held by historically excluded groups. Implementation tools can include community advisory councils,annual equity audits,and conditional public funding tied to demonstrable outcomes. By embedding these prescriptive measures into governance and practice, golf can align its rulebook and course architectures with a social compact that promotes equitable access and long-term vitality.

Future Trajectories for Heritage, Environment, and Technology: Integrating Conservation, Climate Resilience, and Digital Innovation with Strategic Policy recommendations

Conservation of historic golf landscapes must be reframed as an exercise in systems integration: individual preservation actions should be treated as additive slices that compose a resilient whole. Drawing on frameworks analogous to mathematical integration-where the aggregation of local interventions yields a global result-designers and managers can reconcile authenticity with necessary adaptation. This means privileging repair over replacement of heritage features, documenting change pathways, and establishing clear thresholds for intervention so that cultural values persist even as the physical fabric evolves under environmental stress.

Climate resilience strategies must be embedded in everyday operational decisions and supported by targeted policy instruments. Effective measures include:

- Water stewardship: calibrated irrigation, reuse systems, and drought-triggered playability protocols;

- Biodiversity corridors: integrating native plant buffers and habitat patches to enhance ecosystem services;

- Soil-carbon management: turf and rough treatments that increase sequestration while reducing chemical inputs;

- Adaptive turf regimes: species mixes and mowing/traffic schedules that respond to seasonal extremes.

These actions should be linked to performance-based incentives so that environmental gains are measurable and financially sustainable.

Digital innovation can act as the connective tissue between heritage objectives and environmental outcomes, enabling precision interventions and inclusive stewardship. Sensor networks, high-resolution GIS mapping, and digital-twin models permit iterative scenario-testing of restoration options and climate responses, while player-facing tools (augmented caddies, mobile routing) can shape on-course behavior to reduce ecological footprints. A concise set of technologies and expected payoffs is summarized below for planning prioritization:

| Technology | primary Benefit | Implementation |

|---|---|---|

| Soil & moisture sensors | Optimize irrigation | Short-term |

| GIS & historic mapping | Guide restoration | Medium-term |

| Digital twin modelling | Stress-testing scenarios | Medium-long-term |

Policy must catalyse the alignment of heritage, environment, and technology through clear targets, cross-sector governance, and flexible finance.Recommended instruments include performance-based regulatory standards, conservation easements tied to adaptive maintenance plans, publicly supported retrofit grants for resilient infrastructure, and data-sharing mandates to enable comparative learning. crucially, evaluation frameworks should mirror integrative thinking-aggregating discrete indicators (ecological, cultural, fiscal) into composite metrics that track cumulative outcomes and inform adaptive management. By institutionalizing integrative processes, the sector can preserve its legacy while preparing courses and communities for an uncertain climate and rapidly evolving digital landscape.

Q&A

Q: what are the historiographical foundations for studying the evolution of golf?

A: Scholarship on golf draws on sports history, material culture, social history, and the history of technology and landscape design. Primary sources include early rule books and club minute books (mid-18th century onward), contemporary periodicals, patent and manufacturing records for equipment, architectural plans and photographs for courses, and governing-body archives (notably British and American organizations). Comparative and transnational approaches-examining how practices moved between Scotland, England, North America, and the Empire-are especially useful for understanding variation and diffusion.

Q: Where and when did golf originate, and how reliable is the evidence?

A: The modern game of golf emerged in Scotland, with documentary references from the late medieval period and clear institutional evidence by the 16th-18th centuries.early royal accounts and municipal records confirm playing in Scotland; more systematic documentary evidence (club records, tournament regulations) appears in the 18th century. Becuase evidence is uneven, historians emphasize continuity of practice (ball-and-club play on coastal and inland grounds) rather than a single moment of “invention.”

Q: How did the first written rules of golf arise and what were their characteristic features?

A: Written rules emerged in the mid-18th century to regulate competitions among organized societies of players. Early codes were succinct and pragmatic-covering teeing,play order,obstacles,scoring,and conduct-and reflected local conditions and etiquette. They formalized expectations within clubs and laid the groundwork for later standardization.

Q: when and why did the 18‑hole convention become dominant?

A: The 18‑hole yardstick crystallized at st Andrews in the 18th century. The old Course’s reconfiguration in the mid‑1700s produced an 18‑hole round that, through St Andrews’ prestige and the influence of its societies, became widely emulated. The convention diffused as clubs sought comparability for competition and handicapping; by the late 19th and early 20th centuries, 18 holes had become the standard for competitive and recreational rounds.

Q: How did national and international governance shape the standardization of rules?

A: Governing bodies in Britain and the United States-institutions that evolved from local clubs and national organizations-played central roles. These bodies codified rules to resolve disputes, ensure fairness in competition, and manage the sport’s international expansion. Cooperative efforts between British and American rule-makers in the 20th century produced increasingly harmonized codes, enabling international tournaments and cross-border play.

Q: What have been the major phases in golf‑course design?

A: Course design has passed through several broadly defined phases:

– Links and vernacular courses: seaside and common-ground layouts that used natural dunes and contours.- 19th-century formalization: landscaping and routing decisions became more deliberate as clubs multiplied.

– The “Golden Age” (early 20th century): architects (working in Britain and the U.S.) formalized strategy,routing,and hazards,emphasizing risk/reward and aesthetic composition.

– Mid- to late‑20th century: larger earth-moving projects, championship-scale courses, and increased mechanization.- Late‑20th and 21st century: movements toward “minimalism,” restoration of historic links characteristics, sustainability-focused design, and integration of ecological practices.

Q: How have technological changes in clubs and balls affected play and governance?

A: Equipment innovation repeatedly altered play: the gutta‑percha ball (mid-19th century) replaced handmade leather balls, the Haskell wound core (around 1900) increased distance, steel and later graphite shafts altered club behavior, and metal and then titanium drivers dramatically increased potential driving distance from the late 20th century onward. Each wave of change triggered debates about skill versus technology, spurred revisions of rules (e.g.,groove regulations),and raised concerns among governing bodies about the integrity and comparability of historical records and course relevance.

Q: What regulatory responses have ther been to equipment-driven performance gains?

A: Governing bodies have used rules, testing protocols, and equipment standards to constrain or manage the impact of technology-limiting clubhead features, groove shapes, and, more recently, considering measures related to distance. These responses balance preserving traditional challenge and strategic variety with allowing reasonable technological progress, and they often provoke intense stakeholder debate among manufacturers, players, and clubs.

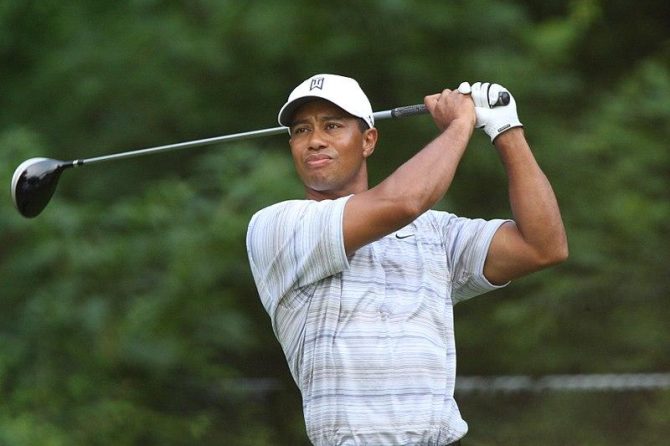

Q: How did professionalization and commercialization transform golf in the 19th and 20th centuries?

A: Professionalization began with local club professionals and greenkeepers in the 19th century and matured into organized tours, professional associations, and prize-money circuits in the 20th century.Commercialization accelerated with corporate sponsorship, televised coverage (mid‑20th century onward), and the development of global tours. These changes altered incentives,elevated elite competition,increased public visibility,and reshaped labor relations within the sport.

Q: How has golf’s social composition changed over time with respect to class, gender, and race?

A: Historically, golf in Britain and elsewhere was associated with elites and exclusive clubs that restricted membership by class, gender, and sometimes race. From the late 19th century onward, multiple forces-urbanization, municipal course building, the rise of working- and middle-class leisure, wars and social reform, and later civil-rights and gender‑equality movements-gradually broadened participation. Women’s and minority participation advanced through separate institutions and, later, integration in clubs, professional tours, and policy. Nevertheless,structural inequalities-economic barriers,membership practices,and cultural legacies-persist and remain topics of reform and research.

Q: What role have public courses and municipal policy played in democratizing golf?

A: Municipal and public courses, often developed in the 20th century, provided lower‑cost access and facilitated broader participation. Policy initiatives (postwar recreation programs, New Deal-era projects in the U.S., municipal park commissions) built infrastructure for mass participation. Public facilities have been central to efforts promoting youth golf, community access, and inclusion, although disparities in quality and resources between public and private facilities endure.

Q: How has broadcasting and media shaped the modern game?

A: Radio and television transformed golf from a localized, club‑based pastime into a global spectator sport.Broadcasts standardized rules and narratives, elevated star players, generated new revenue streams (sponsorships, rights), and influenced scheduling and course setup to produce more viewer-friendly events. Media exposure also intensified commercialization,affected tournament architecture (e.g., hole locations and tee placements), and magnified debates about equipment and distance.

Q: What are the principal environmental and sustainability challenges facing golf today, and how is the sector responding?

A: Key challenges include water consumption, chemical inputs for turf management, habitat alteration, and carbon footprints associated with course construction and maintenance. Responses include drought-tolerant turf research, recycled water use, integrated pest management, native vegetation corridors to support biodiversity, certification schemes, and site-specific design that minimizes earth-moving. There is growing scholarship and practice that reframes courses as multifunctional landscapes with ecological and social benefits.Q: What methodological approaches are most productive for future research on golf’s evolution?

A: Multiproxy methodologies combining archival research, landscape archaeology, oral history, material culture studies (equipment and clothing), and quantitative analysis of participation and economic data are valuable. Comparative transnational studies, attention to marginalized actors (women, minority groups, professionals), and interdisciplinary work linking environmental science and design history promise fresh insights.Digital humanities-mapping course change, modeling equipment impacts, and analyzing media representations-also offer powerful tools.

Q: What are current and emerging debates that scholars and practitioners should follow?

A: Ongoing debates include: how to reconcile technology-driven distance gains with historical integrity and competitive balance; equity of access and the legacy of exclusionary club practices; the role of golf in sustainable land-use planning and climate adaptation; and governance models that balance global standardization with local conditions. Additionally, the interplay between elite professional spectacle and grassroots participation raises questions about the sport’s social purpose and future trajectory.

Q: Where can readers find authoritative primary and secondary sources on these topics?

A: Authoritative material is available in club and governing-body archives, historical rulebooks, patent and manufacturing records, contemporary newspapers and periodicals, and specialized monographs in sports history, landscape architecture, and material culture. Key institutional repositories (national libraries, R&A and USGA archives, municipal archives for public-course history) and peer-reviewed journals in sports history and cultural geography are especially useful.

Conclusion

This study has traced golf’s transformation from a regional pastime in 15th-century Scotland to a globally institutionalized sport, demonstrating how its rules, courses, and social meanings have co-evolved. The codification of rules has both stabilized play and generated sites of contestation as technology, commercial forces, and shifting norms have prompted successive revisions. course design, likewise, reflects a dialogue between aesthetic ideals, strategic intent, and environmental and economic constraints; linkslandscapes, parkland estates, and modern resort complexes each embody distinct cultural priorities. Socially, golf’s history reveals changing patterns of access, identity, and leisure: class and gender barriers have been both reinforced and progressively contested, while globalization and media exposure have reshaped who plays, watches, and governs the game.Looking forward, scholars and practitioners must attend to three interrelated imperatives. First, rigorous historical and sociological inquiry should continue to unpack how rules and built environments mediate power relations and meanings. Second, policy and design responses must reconcile competitive integrity with sustainability and inclusivity, confronting the environmental footprint of courses and persistent inequalities in participation. Third, interdisciplinary engagement-drawing on history, geography, economics, and cultural studies-will be essential to anticipate how emerging technologies and shifting social values will reconfigure play and governance.

By situating contemporary debates within a longue durée perspective, this analysis emphasizes that golf’s durability rests on its capacity to preserve core traditions while adapting to new material and social conditions. Continued critical attention will ensure that adaptations are informed by both respect for the sport’s heritage and a commitment to equitable, sustainable futures.