The long arc of golf’s growth offers a concentrated lens on how athletic practice,social patterns,and material technologies interact. What began as a regional pastime played across Scottish coastal “links” in the late medieval period has become a global sport with formalized regulations, professional tours, and recognizable course typologies. This revised study, “The Historical Evolution of Golf: An Academic Study,” places the game’s transformations in dialogue with economic change, technological innovation, and cultural shifts, following how rules, practices, and meanings were fashioned, debated, and institutionalized from the fifteenth century through today.

Drawing on surviving primary materials (early rule collections, club minutes, original course schematics, and contemporary commentaries) alongside scholarship in sports history, cultural analysis, and landscape design, the essay examines three overlapping vectors of change: the production and spread of governance and rules; the emergence and categorization of course types (from natural links to landscaped parklands and large championship complexes); and the two‑way relationship between social transformations-class formation, imperial circulation, commercialization, and struggles over gender and racial inclusion-and the rituals and customs of the game. The analysis also attends to equipment and turf technologies, and to the expanding influence of media and professional structures on perceptions of leisure, competition, and celebrity. Integrating institutional,material,and cultural viewpoints,the piece synthesizes existing debates while proposing interpretive models that explain regional variation and international diffusion. The remainder of the article is organized both chronologically and thematically: early origins and codification; nineteenth‑century diffusion and club formation; twentieth‑century modernization and professionalization; and present‑day continuities and challenges-access and diversity, environmental stewardship, and the commercialization of heritage. This organization demonstrates that golf’s traditions are not fixed relics but continually reworked responses to shifting historical circumstances.

Origins of Golf in Fifteenth Century Scotland Evidence, Archaeology, and Documentary Analysis

Reconstructing early golf in Scotland requires weaving together diverse source types: parliamentary statutes, household and treasury ledgers, historic maps and place‑names, and the material remains preserved in coastal links landscapes. Each category supplies a different temporal and social resolution-laws indicate official responses to popular recreation, account books register elite involvement, while toponymy and archaeology reveal where and how ordinary play unfolded. Because no single archive offers an uninterrupted narrative from the fifteenth century onward, a multi‑disciplinary synthesis is essential.

When brought into conversation, documentary traces become especially persuasive. The frequently cited 1457 parliamentary prohibition-issued to encourage archery training by limiting other leisure pursuits-functions as indirect testimony to an already established ball‑and‑club pastime. Likewise, early sixteenth‑century treasurer records that note expenditures and activity around Leith and St Andrews point to elite engagement and the social visibility of the game. These administrative documents must be interpreted in light of their bureaucratic genres and political aims: they show prevalence and perception rather then providing detailed descriptions of play or codified rules.

- Legislative records – statutory bans and regulations reflecting social control

- Treasury and household accounts – recorded expenses, gifts, and patronage linked to play

- Toponymy and mapping – surviving place‑names bearing “links,” “bal,” or “golf”

- Archaeological finds – fragmentary club heads, ball remnants, and turf disturbance signatures

- Visual and material culture – artistic depictions, carved motifs, and preserved implements

Material and landscape evidence complements the written record and imposes constraints on what play could have looked like. Natural dunes and common grazing grounds called “links” generated linear playing corridors and influenced shot selection; micromorphological soil studies and turf stratigraphy at historic sites record long‑term trampling consistent with repeated ball play. Finds of early club fragments and later wooden headstocks-while infrequent-help build typologies of equipment change, but organic preservation bias means many items are lost to time. Consequently, the absence of artefacts is an interpretive issue that must be handled carefully.

Advances in geoarchaeological and remote‑sensing methods have expanded what can be reconstructed from the landscape. Pollen analysis, soil‑core stratigraphy, LiDAR and aerial photogrammetry, and targeted geophysical prospection permit reconstruction of early fairways, green complexes, and trampling signatures at a scale not possible from documents alone. These techniques, combined with archival cartography and place‑name studies, enable more precise mapping of where early play occurred and how course morphologies changed over time.

Taken together, these lines of evidence sketch a plausible account: by the late fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries, a recognizable ball‑and‑club game appears in municipal and royal records and is practiced within specific coastal settings. The table below highlights principal documentary markers and what they tell us about the sport’s early institutionalization.

| Document | Approx. Date | Interpretive Value |

|---|---|---|

| Parliamentary Act | 1457 | Indicates the game’s prevalence and official efforts to shape leisure |

| Treasurer’s accounts | Early 1500s | Evidence of royal engagement and place‑based practice (Leith, St Andrews) |

| Cartography / Place‑names | 16th-17th c. | Continuity of landscape terms and the spatial footprint of “links” |

In sum, an evidence‑led narrative of golf’s fifteenth‑century emergence emphasizes converging indicators-legal, fiscal, cartographic, and material-rather than depending on a single proof. Methodologically, historians should temper strong claims about early technique or formal rules, which are better documented in later centuries, and instead prioritize further interdisciplinary investigations: focused archaeological surveys at early links; systematic digitization of municipal archives; and careful textual analysis situating the game within the social and economic shifts of late medieval Scotland.

Codification of Rules from Early Customs to Modern Governance Institutional Lessons and policy Recommendations

The emergence of written rules marks golf’s transition from locally negotiated custom to widely recognized standards. Early play adapted to local ground, oral understandings, and club conventions; over time, these informal practices were translated into written prescriptions to reduce ambiguity about play, equipment, and conduct. That translation converted tacit knowledge into enforceable norms and made rulebooks the definitive arbiter of fairness in contest situations.

Institutional consolidation-through national bodies and later international cooperation-was central to the diffusion and legitimacy of codified rules. Organizations took duty for reconciling regional variations and setting standards for how disputes, equipment, and player behavior should be managed. Institutional governance brought consistency, a formal process for rule revision, and structured education, but it also created tensions between uniform global standards and the particularities of local courses and cultures. This history points to the value of governance models that pair central guidance with contextual sensitivity.

Codification produced trade‑offs that remain relevant for contemporary reform: clearer, portable standards reduce ambiguity and support cross‑jurisdictional competitions, yet centralization can also limit local innovation and concentrate interpretive authority. Policy designs should therefore balance clarity with subsidiarity so that rules secure fairness while permitting measured local adjustments where appropriate.

From a policy perspective, several practical recommendations flow from this trajectory:

- Scheduled reviews: Institute regular cycles for evaluating rules so they respond to technical and cultural change.

- Inclusive stakeholder input: Create formal channels for players, clubs, manufacturers, and officials to participate in rule development.

- Obvious rationale: publicize the reasoning behind major rule changes and prominent interpretations to strengthen acceptance.

- education and training: Invest in scalable programs so rules are consistently understood and applied at all levels.

- Contextual subsidiarity: Permit measured local adjustments where course‑specific conditions require, within a central framework.

Operationalizing these principles depends on governance tools and careful monitoring. The following matrix summarizes mechanisms and likely policy outcomes:

| Governance Mechanism | Policy Implication |

|---|---|

| Central rulebook | Uniform benchmarks for adjudication and education |

| Local Dispensations | Adaptability to reflect local conditions; potential divergence risk |

| Scheduled Reviews | greater responsiveness to innovation and social change |

| Transparent Rationale | Improved legitimacy and stakeholder buy‑in |

Several broad lessons follow. First,codification should balance permanence with adaptability: rules must secure fairness yet allow for measured evolution. Second, legitimacy comes from participatory processes and clear justifications, not only from formal authority.Third, translating written norms into everyday practice requires accessible education and dispute‑resolution pathways. ongoing empirical evaluation-tracking rule impacts and compliance-should inform iterative policy refinement to sustain the sport’s ethical and competitive foundations.

Evolution of Course Design and Landscape Aesthetics Environmental Implications and Restoration Strategies

Course architecture has evolved in response to shifting social tastes, technological possibilities, and environmental constraints. Where early links offered minimally modified routes across dune systems, nineteenth‑century sensibilities introduced the parkland aesthetic: engineered tees and manicured fairways framed by ornamental planting, enabled by mechanized earth movement. Modern design ranges from efforts to restore naturalistic character to the construction of highly engineered championship venues; each phase represents selective retention and reinvention rather than linear progress.

Aesthetic priorities moved from penal hazards to strategic design and, more recently, to ecological integration. Pioneers such as Old Tom Morris and Alister MacKenzie blended playability with scenic composition; later architects emphasized sculpted bunkers and immaculate surrounds as markers of prestige. Today’s design vocabulary increasingly incorporates native roughs, pollinator corridors, and sightlines that balance play value with ecological coherence.In place of an evolutionary metaphor, think of course design as an ongoing dialogue between cultural preferences and environmental affordances.

Historic practice and conventions have also shaped how architects organize a full round. The standardization of the eighteen‑hole round in the late nineteenth century was particularly consequential: it transformed routing practice by imposing expectations for sequential variety, balance between opening and finishing holes, and cumulative challenge across a full round. Architects began to conceive courses as coherent narratives rather than isolated holes, attending to transitions, strategic diversity between front and back nines, and the management of cumulative fatigue and psychological momentum. Sequencing choices therefore anticipate factors such as light and weather variation over the duration of play-practical concerns that affect shot selection, pace, and fairness.

Environmental stewardship has become central to modern adaptation of both classic and contemporary routing models: larger footprints magnify impacts on hydrology,biodiversity and carbon budgets,while also offering opportunities for integrated habitat corridors and multifunctional landscapes. Mitigation approaches include phased construction to reduce earthworks, native‑plant buffers to enhance connectivity, and adaptive routing that minimizes long‑term maintenance burdens while preserving strategic diversity. Practically, clubs should adopt lifecycle approaches-prioritizing design elements that reduce long‑term maintenance costs and ecological impacts so the established convention of an eighteen‑hole round remains both playable and ecologically responsible.

historic practices have also created environmental challenges. Extensive turf monocultures, heavy irrigation, and routine agrochemical use have measurable consequences for water budgets, soil condition, and biodiversity. The table below outlines broad era characteristics, associated environmental pressures, and representative mitigation responses that have emerged.

| Era | Characteristic | Environmental Concern | Design Response |

|---|---|---|---|

| Links / pre-1800s | Light intervention | Dune instability and erosion | Dune restoration and fencing |

| parkland / 1800-1930 | Ornamental turf and planting | High potable water demand | Buffer planting and native belts |

| Modern / Post-1960 | Engineered and intensively managed | Habitat fragmentation and chemical inputs | Ecological retrofits and reduced mowing |

Restoration strategies now draw on ecology, agronomy, and landscape planning to align playability with ecosystem services. Typical interventions include:

- Hydrological redesign to curtail potable water use and capture stormwater;

- Native re‑vegetation to rebuild local plant communities and attract pollinators;

- Soil rehabilitation using organic amendments, composting, and less disruptive cultivation;

- Integrated pest management that replaces blanket chemical applications with targeted, evidence‑based controls;

- Wildlife buffers and corridors to reduce fragmentation and improve connectivity;

- Seasonal mowing protocols and native‑turf restoration approaches that balance playability with biodiversity and reduce input needs.

These measures are most effective when tailored to local soils, climate regimes, and cultural priorities, and when they retain the tactical elements that define play.

Looking ahead, an evidence‑driven design practice emphasizes adaptive management, long‑term monitoring, and collaborative decision‑making. Tools such as GIS habitat modelling, life‑cycle assessments for turf inputs, and periodic biodiversity surveys allow designers to assess outcomes and refine interventions. As of the early 2020s there are roughly 34,000 golf courses worldwide and tens of millions of active players, reinforcing both the scale of potential environmental impact and the opportunity for systemic enhancement. The future of course landscapes lies in integrated strategies that balance aesthetic legacy, recreational utility, and ecological resilience-treating courses as living social‑ecological systems under continuous stewardship.

Technological Innovations in Equipment Effects on Play, Competitive Equity, and regulatory recommendations

Recent decades have seen engineering developments that substantially affect shot performance and strategic choices on course. Advances in clubhead aerodynamics, mixed‑material construction (titanium, carbon fiber), modern graphite shafts, and multi‑layer golf balls have increased average carry distances and altered spin characteristics. Adjustable weighting systems and face engineering (variable thickness and optimized energy transfer) enable precise tuning of launch conditions, and wearable and sensor analytics speed the refinement of swing mechanics. These trends have translated into measurable improvements in both average and elite performance metrics.

Though, technological progress raises equity questions. Performance gains often correlate with financial resources and access to technical support, widening performance gaps between better‑funded competitors and recreational or junior players.Equipment shifts can also recalibrate the relative importance of skills-favoring power and distance over finesse around hazards-thereby changing competitive balance and complicating comparisons across eras. Addressing these concerns requires both empirical assessment of differential impacts and normative deliberation about fairness and access.

Governing bodies have sought to set technical boundaries to preserve skill and historical continuity. Limits on ball velocity, driver head dimensions, groove geometry, and shaft length-implemented through measurable tests such as COR and initial velocity protocols-illustrate efforts to cap technologically driven performance increases. Yet lab standards cannot always reproduce dynamic on‑course conditions, and rapid incremental innovation can outpace formal rule cycles.

A practical regulatory approach should combine scientific rigor, transparency, and staged implementation. Recommended actions include:

- Open standardized testing with published methods and autonomous verification;

- Regular technology impact studies that quantify equipment effects across skill levels and demographic groups;

- Phased restrictions with grandfathering and transition periods to reduce market disruption;

- Access programs that provide equipment and training to developmental players to mitigate resource‑based inequalities.

Together, these measures aim to ground equipment governance in evidence while limiting abrupt distortions to competitive parity.

The table below links illustrative innovations to their playing effects and possible regulatory responses:

| Innovation | Effect on Play | Regulatory Response |

|---|---|---|

| High‑COR faces | Greater carry distances and margin‑shifting drives | Limit COR; standardized velocity testing |

| Adjustable weighting | Fine‑tuned launch and spin characteristics | Define tolerances; require transparent labeling |

| Performance multi‑layer balls | Variable spin and distance across clubs | Set maximum initial velocity; conduct playability assessments |

Social and Cultural Transformations Inclusivity, Class Dynamics, and Globalization Recommendations for Access and Diversity

Over its long history, golf’s social meanings have shifted-from a marker of elite sociability toward contested public terrain. Industrialization and the expansion of middle‑class leisure in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries broadened participation and consumption patterns. Simultaneously occurring,the ideal of amateurism encoded class distinctions and served as a gatekeeping principle that shaped club rules,tournament practices,and the valuation of particular styles of play.

Barriers to entry have been structural and intersectional, combining gender, race, and economic status. These constraints took shape in formal membership policies, the geographic siting of courses and transport links, and the direct costs of equipment and play. Persistent obstacles include:

- High membership and green fees that exclude lower‑income players

- Club governance norms that perpetuate social homogeneity

- Insufficient visibility and funding for women’s and minority development programs

- Uneven distribution of public facilities, disadvantaging urban and low‑income neighborhoods

Addressing these entrenched patterns requires coordinated institutional strategies rather than isolated fixes.

The sport’s global spread-through imperial networks, expatriate communities, and twentieth‑century mass media-has produced localized hybrids combining Scottish forms with regional aesthetics and commercial models. The schematic below summarizes generalized regional trajectories:

| Region | Transformation |

|---|---|

| Scotland | Early codification and deep tradition |

| United States | Widespread participation and commercial expansion |

| Asia | Rapid development with strong elite sponsorship |

| Africa & Latin America | Growing public programs and emerging markets |

These global flows created new governance hybrids and commercial opportunities but also reproduced inequalities where capital and media attention concentrated in privileged markets.

Contemporary class dynamics are mixed: exclusive private clubs and luxury resorts coexist with municipal courses, driving ranges, and public initiatives that broaden participation. Policy choices-zoning, public investment, youth funding-play a decisive role in shaping access. Evaluations should combine quantitative indicators (for example, per‑capita public course availability and price sensitivity of participation) with qualitative data (participant experiences and governance inclusivity) to measure progress meaningfully.

Recommendations to enhance access and diversity should be systemic and evidence‑driven. priority steps include:

- Expanding publicly funded, low‑cost facilities in underserved areas

- Creating targeted scholarships and equipment‑loan programs for youth from low‑income families

- Requiring diverse representation on club and governing boards

- Investing in coach education to reduce bias in talent development

- Forging partnerships between governing bodies, schools, and community organizations to build long‑term pipelines

implementing these measures needs clear performance metrics, scheduled reviews, and funding approaches that align commercial incentives with public goals so that golf’s heritage can coexist with contemporary demands for inclusion.

Professionalization,Tournaments,and Media Economies Governance Challenges and Strategies for sustainable Development

During the twentieth and twenty‑first centuries,golf shifted from localized play to a professionalized labor market with defined career structures,contracts,and performance indicators. National associations and tour organizations formalized membership and ranking systems, producing a two‑tiered ecosystem of major tours and developmental circuits. Prize purses and sponsorship inflows ballooned,altering player incentives and club finances,and prompting regulatory attention to subjects such as player movement,integrity safeguards,and anti‑corruption protocols.

Simultaneously occurring, the sport’s media economy became a key driver of governance and revenue. Broadcast agreements, streaming platforms, and branded digital content now shape tournament formats, scheduling, and commercial valuations. Audience measurement, targeted advertising, and platform exclusivity introduce negotiating pressures that can both support and constrain broader development aims.

Governance problems are multiple and must be addressed collectively. Principal issues include:

- Regulatory fragmentation across national authorities and commercial tours;

- Economic concentration where a few broadcasters or sponsors dominate revenue flows;

- Environmental impacts tied to course construction and event logistics;

- Access and equity shortfalls for underrepresented groups;

- Long‑term grassroots viability amid rising costs and commercial pressures.

| Challenge | Strategic Response | Indicative Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| Regulatory fragmentation | Inter‑organizational compacts and harmonized standards | Smoother player progression and clearer rules |

| Economic concentration | Revenue‑sharing frameworks and platform diversification | Greater financial resilience for stakeholders |

| Environmental impacts | Mandatory sustainability standards and water stewardship | Lower ecological footprint of events and venues |

A sustainable development strategy should combine governance reform with market instruments. Recommendations include transparent tendering for media rights, mandatory environmental performance criteria for tournaments and venues, and channeling a defined portion of broadcast and sponsorship revenues into community programs and talent development. prioritizing data‑driven monitoring, stakeholder participation, and adaptive policymaking will help reconcile commercial growth with long‑term social and ecological responsibilities, preserving competitive quality while enhancing public legitimacy.

Integrating Heritage Conservation with Contemporary Practice Policy Recommendations for Balancing Tradition, Sustainability, and Community Engagement

Policy frameworks that integrate heritage conservation with contemporary use must balance preserving defining physical features-routing, landmark bunkers, clubhouse form-with sympathetic upgrades that improve safety, accessibility, and play standards.This approach treats historic golf landscapes as living inheritances where continuity and change are mutually constitutive, allowing alterations that respect provenance while accommodating current needs.

Putting these principles into practice requires a mix of regulatory protections and incentives: statutory listing and bespoke conservation management plans for verifiable historic sites; design guidelines that specify acceptable materials and landscape interventions; and financial support mechanisms-tax credits, conservation easements, grants-to underwrite careful restoration and sustainable modernization. Governance models from other heritage sectors-such as adaptive reuse strategies employed at industrial park conversions and community stewardship programs-offer practical templates for managing golf heritage in ways that combine narrative preservation with economic viability.

Complementary policy instruments are especially important. In addition to conservation grants and planning protections, practitioners should consider:

- Documentary consolidation: systematic digitization of club records, maps, and oral histories to create interoperable archives;

- Protective zoning: legal recognition of historic courses and linksland as cultural landscapes to limit incompatible development;

- Conservation‑sensitive maintenance: agronomic regimes that balance playability with biodiversity-reduced chemical inputs, native turf restoration, and seasonal mowing protocols;

- Community engagement: programs that involve local stakeholders in monitoring, interpretation, and stewardship to sustain intangible practices alongside physical preservation.

Community engagement must be central rather than peripheral. Effective participation strategies include:

- Co‑design sessions with club members, neighbors, and Indigenous or local stakeholders to map values and vulnerabilities;

- Partnerships with schools and heritage organizations to create interpretive programming;

- Volunteer stewardship groups for light maintenance and monitoring that cultivate local custodianship.

These practices promote plural and accountable custodianship and ensure conservation plans reflect both historic and social values.

Environmental performance should be embedded within conservation criteria. Policies should emphasize water‑sensitive design, reduced reliance on agrochemicals, and on‑site biodiversity gains within fairways and roughs. The following table sets out concise policy goals and measurable indicators for practitioners and policymakers:

| Policy | objective | performance Metric |

|---|---|---|

| Water Reuse & Irrigation Efficiency | Cut potable water consumption | Annual potable water use (m³/ha) |

| Native Vegetation corridors | Raise on‑site biodiversity levels | Native species cover (%) |

| Reduced Chemical Regimes | Lower ecological and public‑health risks | Kg active ingredient/year |

Robust monitoring and adaptive management are indispensable. Policies should mandate baseline documentation (archival records, GIS mapping, ecological surveys), regular review intervals, and public reporting platforms that allow stakeholders to prioritize interventions according to condition and use pressures. Sustainable funding models-mixing public heritage grants, private capital, and community fundraising-will be necessary to support long‑term stewardship. in short, the recommended policy architecture centers on evidence‑based conservation, participatory governance, and ecological resilience, enabling a balance between the preservation of golf’s material heritage and contemporary recreational and community needs.

Q&A

Note on sources

– the search results supplied with the original brief did not include dedicated golf historiography; the Q&A that follows synthesizes widely accepted scholarly conclusions about golf’s past and methods rather than drawing on those particular links.If you prefer, targeted archival or bibliographic searches can be added for precise citations.

Q&A: The Historical Evolution of Golf – An Academic Study

1. Q: What evidences the sport’s earliest origins and early codification?

A: Documentary traces for golf surface in late medieval and early modern Scotland. Ball‑and‑club games are mentioned in fifteenth‑century records, and by the eighteenth century institutionalization became visible through organized clubs and printed rules (for example, the 1744 rules issued by the Company of Gentlemen Golfers in Leith). these milestones formalized play, scoring, and etiquette, laying foundations for later national governance.

2. Q: How did informal local rules give way to standardized codes?

A: Early customs varied by place and club and were regulated informally. As clubs multiplied in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries and interclub contests increased, harmonization became necessary. National authorities-most prominently the Royal and Ancient Golf Club at St Andrews and later the United States Golf Association (founded in 1894)-assumed rule‑making responsibilities. Cooperative efforts between bodies like the R&A and USGA have since produced unified rule editions (notably the complete 2019 revision) that address equipment, pace of play, and international applicability.

3. Q: How have equipment changes affected golf?

A: Transformations in balls and clubs have repeatedly reshaped play. Historical shifts-from the featherie to gutta‑percha, to wound rubber cores, and finally to modern multi‑layer solid cores-along with changes in shaft materials from hickory to steel and graphite, and evolving head designs, have all influenced distance, shot‑making, and how courses test players.Regulatory bodies have responded to such technological shifts to maintain competitive balance.

4. Q: What are the major stages in course‑design history?

A: Originally, play occurred on natural links with little modification. From the nineteenth century onward, designers like Old tom Morris and Alister MacKenzie introduced strategic routing and shaped greens and hazards; later architects such as Donald ross and James Braid contributed regional variations. The twentieth century saw large‑scale earthworks, irrigation systems, and the rise of parkland and resort courses. Each phase reflects technological capacity, client expectations, and changing aesthetic and strategic priorities.

5. Q: What factors accelerated golf’s spread and institutionalization?

A: Industrialization, urban population growth, expanding leisure time among the middle classes, and improved transport (railways) all expanded participation. Imperial connections and migration exported Scottish forms worldwide; military personnel and colonial administrators helped establish clubs overseas. The professionalization of athletes, sponsorship, and mass media in the twentieth century further multiplied the game’s reach.6. Q: how have social categories-class, gender, race-influenced golf’s history?

A: Golf has been shaped by social hierarchies. Early clubs were elite social spaces; the amateur‑professional divide reinforced class distinctions. Gender exclusion produced separate institutional developments (such as, early women’s organizations), and racial exclusion-most visible in some national contexts-restricted access until reform movements in the mid‑ to late‑twentieth century. Contemporary scholarship emphasizes these inequalities and highlights previously marginalized actors and institutions.

7. Q: What role have governing organizations played in international rule standardization?

A: National bodies standardized rules, handicapping systems, and championship formats while organizing major tournaments. Cooperative action-especially between the R&A and USGA-has been crucial to harmonizing rules internationally and coordinating responses to equipment and other innovations.Professional tours also created transnational pathways and unified competitive circuits.

8. Q: What impact did television and mass media have on golf?

A: From the mid‑twentieth century, broadcast media turned golf into a spectator sport with large audiences. Television brought increased sponsorship, influenced scheduling and format choices, and elevated star players, reshaping public perceptions of skill and celebrity. Course features were sometimes adapted to create visually compelling holes for broadcast audiences.9. Q: What environmental and land‑use issues accompany golf’s expansion?

A: Course construction and maintenance raise concerns over water consumption, pesticide use, habitat loss, and land conversion. From the late twentieth century onwards, sustainability movements prompted changes in turf management, design approaches that reduce maintenance intensity, and participation in certification schemes (for instance, Audubon Cooperative Sanctuary programs) to mitigate impacts.

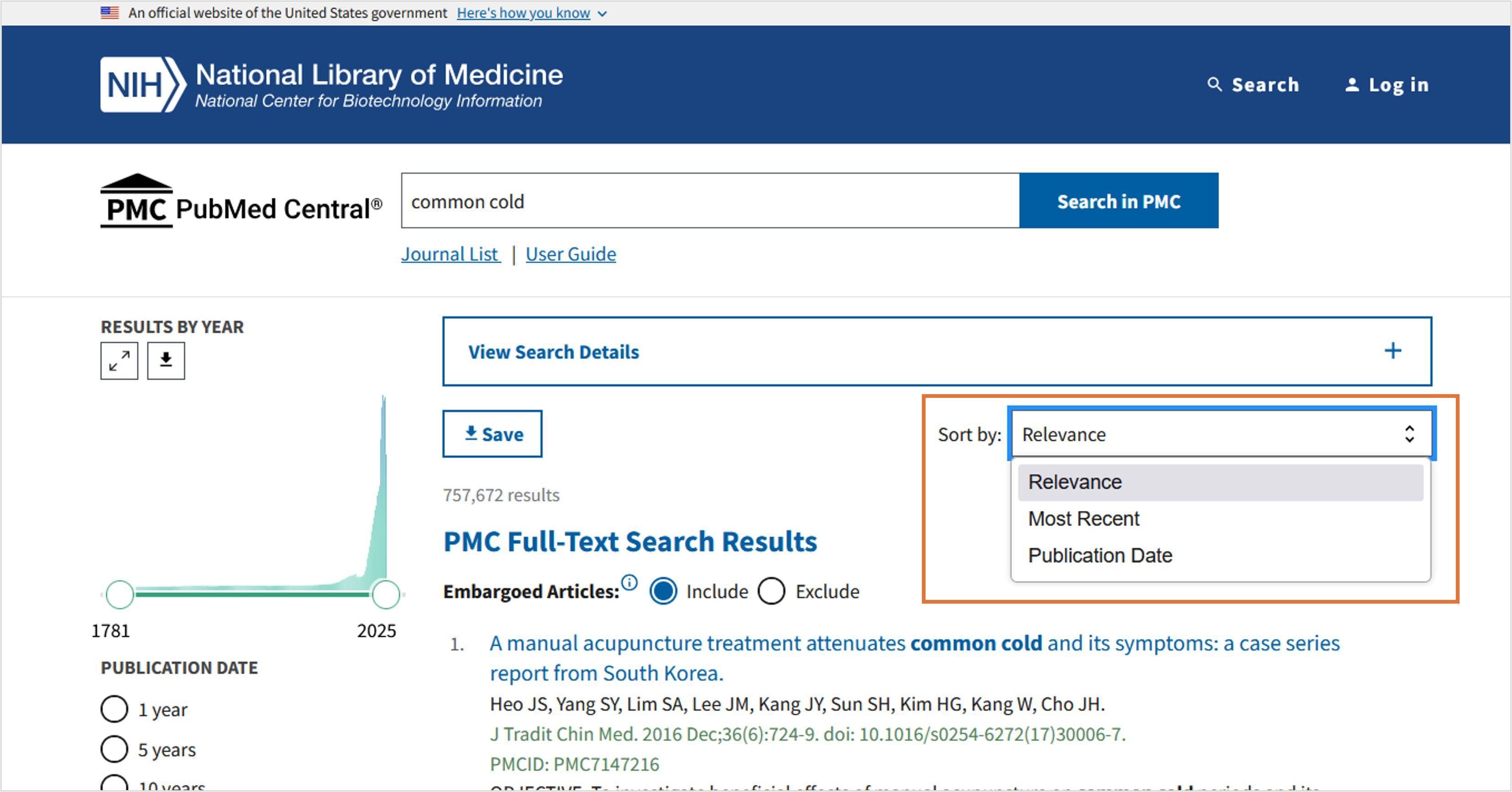

10. Q: Which research methods do historians use to study golf?

A: Researchers employ archival work (club minute books, rules, newspapers), oral history, material culture studies of clubs and balls, landscape archaeology (including soil and turf studies and remote sensing), and quantitative analyses of economic and participation data. Interdisciplinary approaches-blending social,cultural,and environmental history with sports science-are increasingly common.

11. Q: What are the leading historiographical debates?

A: Debates concern the extent of golf’s elitism versus popularization, the role of empire and colonial processes in diffusion, technology’s impact on fairness and tradition, and the influence of gender and race on institutional development. Recent work stresses underrepresented groups and critiques nostalgic narratives of a single “traditional” golf.

12. Q: Who have been influential individuals and institutions?

A: Key figures include architects and early practitioners such as Old Tom Morris, Alister MacKenzie, and Donald Ross; governing institutions like St Andrews, the R&A, and the USGA; and prominent players whose celebrity reshaped the sport. Major clubs, national unions, and tour organizers have been decisive in defining rules, prestige, and practices.

13. Q: How have competition formats shaped culture and conduct?

A: Match play, with its head‑to‑head emphasis, was historically central in clubs and early championships. Stroke play rose in prominence with national opens and tournaments suited to large fields and broadcast formats. Each format privileges different strategies and affects spectator appeal and institutional emphasis.

14. Q: What future research agendas are promising?

A: Productive directions include comparative global histories beyond British imperial frameworks; microhistories of marginalized clubs and players; long‑term environmental impact studies; and integrated technological histories that combine engineering analysis with governance and social effects. Digitization of archives and increasingly available statistical datasets open new quantitative avenues.15. Q: What seminar prompts could stimulate advanced discussion?

A: Examples:

– How did club‑level governance translate local customs into global norms?

– In what ways have technological advances reinforced or undermined social hierarchies?

– To what degree is contemporary “traditional” golf a constructed nostalgia shaped by commercial interests?

– Compare the diffusion of golf in two regions (as an example, South Asia vs North America): what local mediations mattered most?

16. Q: which sources are most valuable for scholarly work?

A: Primary sources include club minute books, membership rolls, early printed rules (e.g.,1744),tournament programs,newspapers,and archives of governing bodies (R&A,USGA). Material collections in museums and local club archives are also crucial. Secondary literature in sports history, cultural history, and environmental history provides interpretive frameworks; repositories at St Andrews, the USGA Library, and national libraries are especially rich.Concluding note

– this Q&A consolidates principal themes for an academic account of golf’s historical development: rule institutionalization, course‑design change, technological influence, and shifting social dynamics and methodologies. If desired, the study can be expanded with annotated references, archival citations, or tailored seminar materials for different academic levels.

In Summary

this revision has followed golf’s trajectory from a regional fifteenth‑century pastime in Scotland to a globally institutionalized sport, underlining how rule formalization, course architecture, and wider social and economic forces have together shaped its path. Framing technical developments-rule codification, course design, and equipment innovation-within changing political, cultural, and economic contexts reveals how material practices and symbolic meanings have co‑produced one another.

The historical record points to both continuity and change: many traditions and terms survive even as commercialization, technology, and transnational exchange reconfigure participation, governance, and landscape stewardship.Understanding these dynamics requires attention to multiple scales-from the granular detail of club minutes and design drawings to the macro structures of international governance and media systems-to map how authority, access, and identity have been negotiated over time.

Future scholarship will benefit from comparative, interdisciplinary work that mixes archival research, oral history, spatial analysis, and ecological assessment to probe unresolved questions about gender and class stratification, colonial and postcolonial spread, and the long‑term environmental effects of course management. Such research will refine periodization, clarify causal links, and inform contemporary debates about inclusion, sustainability, and sport’s cultural value.

Ultimately, tracing golf’s historical evolution deepens our appreciation of it as a complex social practice that both mirrors and helps shape broader patterns of modern life. Ongoing scholarly engagement will be essential to understand how historical legacies shape present institutions and to guide responsible stewardship of the game going forward.

Fairways of Time: Tracing the Cultural and Technical Evolution of Golf

Ten Engaging Rewrites – Pick a Tone

- From Links to Legends: A scholarly Journey Through Golf’s History (scholarly)

- Teeing Off Through Time: An Academic Exploration of Golf’s Evolution (academic)

- Fairways of Time: Tracing the Cultural and Technical Evolution of Golf (balanced)

- Strokes of History: The Academic Story of Golf’s Rise and Rules (scholarly)

- From 15th‑Century Scotland to Global Greens: A Study of Golf’s Evolution (historical)

- Green Through the Ages: An Academic Look at Golf’s Transformation (academic)

- Putting History into Play: Scholarly insights into Golf’s Development (scholarly)

- Golf Through the Centuries: An Academic Chronicle of a Timeless Sport (chronicle)

- Tradition, Rules, and Design: An Academic tour of Golf’s Historical Evolution (analytical)

- How Society Shaped the Game: An Academic History of Golf (social/cultural)

Three Tone Samples (Pick one)

Scholarly (for academic journals or curriculum)

Golf’s evolution is best understood as an intersection of material culture, institutional governance, and landscape design. Originating on the windswept links of 15th‑century Scotland, the sport’s formalization-codified in early rules and later by bodies such as the Royal & Ancient Golf Club (founded 1754) and the USGA (founded 1894)-reflects changing socio‑political networks and technologies. This paper synthesizes archaeological, archival, and architectural sources to trace how equipment innovation (e.g., the Haskell rubber‑core ball) and professional organizations shaped modern golf.

Narrative (for a magazine feature)

Imagine a lone figure on a gusty scottish coastline hundreds of years ago,sweeping a wooden club across the sand until a feather‑light ball skitters toward a furrow of grass. That image is where golf begins-and where a centuries‑long story of invention, rivalry, and unabashed tradition unfolds. From humble beginnings on the links to the manicured perfection of Augusta National, golf’s tale is a human one: players, patrons, and designers chasing a dream shot.

Punchy (for social posts or brief web copy)

From sand dunes to superstars: golf transformed from a Scottish pastime to a global game through bold rules, radical gear, and inspired course design. Want the short version? Clubs got smarter, balls got bouncier, courses got craftier-and the game got bigger.

Historical Timeline: Key Milestones in the History of Golf

| Period | Milestone | significance |

|---|---|---|

| 15th century | Early links play in Scotland | Origins: informal play on coastal links |

| 1744-1754 | First rules & Royal & Ancient formation | Formal codification and club governance |

| Late 19th c. | Spread to U.S. & founding of USGA (1894) | International expansion & standardized rules |

| 1898 | Haskell rubber‑core ball | Revolution in distance and technique |

| 20th c. | Steel shafts, metal woods, televised majors | Professionalization and mass audience |

Origins and the Rise of Links Golf

The history of golf is rooted in Scotland’s coastal landscapes-links: sandy, undulating terrain ideal for walking and hitting a ball long distances. Archaeological and written records point to organised ball‑and‑stick games as early as the 15th century. By the 18th century, clubs and societies formed; the Royal & Ancient Golf Club of St Andrews (established 1754) emerged as a central authority shaping early rules and tradition.

Why the links matter

- Natural hazards (wind, dunes) shaped shotmaking and strategy.

- Community access-links were common land where villages could play.

- Course design evolved from constraints of the landscape, not imposed design.

Codifying the Game: Rules, Institutions, and governance

Formal rules began emerging as clubs sought uniformity for competitions. Early written rules (mid‑18th century) were short and pragmatic, addressing ball placement, hazards, and scoring. By the late 19th century, national bodies like the USGA standardized rules internationally, while the R&A continued to steward links traditions and major championships.

Critically important organizational milestones

- 1744: Early published rules (Gentlemen Golfers) – local to Leith/St Andrews region.

- 1754: Royal & Ancient Golf Club formed – central in rule development.

- 1894: USGA founded – coordinated American governance and championships.

- 20th-21st c.: Increasing collaboration and occasional rule modernization (e.g., 2019 rules update).

Equipment Evolution: From Wood to Composite

Material science and craft changed how golf is played. Early clubs were hand‑carved wooden sticks; balls were feather‑filled leather (featheries). The Haskell rubber‑core ball (c. 1898) offered better compression and longer flight, prompting swing and course changes. Steel shafts replaced hickory in the early 20th century,and later graphite and titanium advanced performance. Today’s drivers, irons, balls, and putters are engineered for forgiveness, distance, and consistency.

Key equipment transitions

- Featherie → gutta‑percha → Haskell rubber‑core ball

- Hickory shafts → steel → graphite

- persimmon woods → metal heads → carbon composite drivers

Course Design: Links,Parkland,and Modern Architecture

Design philosophies shifted as golf moved from coastal links to inland parkland and resort courses. Early holes took advantage of natural contours; later designers (Old Tom Morris, Alister MacKenzie, and Donald Ross) combined naturalism with intentional routing to create strategic challenges. Modern architects balance playability, environmental stewardship, and spectacle-especially for televised majors.

Design elements that shaped play

- Routing and teeline placement influence strategic decisions.

- Bunkering evolved from punitive hazards to strategic features.

- Green complexes changed short game demands and putting strategy.

How Society Shaped the Game

Golf developed with social values and class structures woven into club memberships, amateurism rules, and patronage. During the British Empire and later American expansion, golf became a marker of status and a site for business networking. The professional game-PGA (U.S. founded 1916) and international tours-commercialized spectator appeal and athlete careers.Social movements, economic shifts, and globalization have made golf more accessible in many regions, while debates about inclusion, diversity, and land use continue.

socio‑cultural impacts

- Class and membership: private clubs vs. public courses

- Gender and amateurism: gradual inclusion of women and professionals

- Urbanization and land pressures: shifting course development and access

Case Studies: St Andrews and Augusta

Two courses illustrate different traditions.St Andrews (Old Course) epitomizes links history: minimalistic routing, double greens, and a public ethos despite prestige. Augusta National represents a 20th‑century curated landscape-intense attention to aesthetics, member exclusivity, and tournament spectacle. Each site shows how design, governance, and culture interact to shape the modern game.

Practical Tips for Writers, Editors, and Content Creators

- Choose a tone to match your audience: scholarly for journals, narrative for feature magazines, punchy for social media.

- Use long‑tail keywords: “history of golf,” “15th‑century Scotland golf origins,” “evolution of golf equipment.”

- Include timelines and tables to help readers scan historical shifts quickly.

- Bring in primary sources where possible: club archives, early rulebooks, and museum collections.

- Use images with captions (Old course routing, early club photographs, Haskell ball illustration) to break text and boost engagement.

SEO Best Practices & Analytics (How to track impact)

Use a clear meta title and meta description (see top of this article) and include your main keyword phrase in the H1 and at least once in H2 or early paragraph. Monitor how the article performs with Google Search Console and analytics tools:

- Google Search Console (monitor clicks,impressions,and search queries; see support link for guidance).

- Google Analytics/Analytics Academy (learn to set events and measure engagement; see Analytics Academy for training).

- Make content accessible and shareable: concise URLs, social meta tags, and fast page speed.

(Helpful resources: Google Search Console overview and Analytics Academy. Also consider advising readers how to make Google their default search for testing search snippets.)

Suggested WordPress Styling Snippets for Editors

/* Simple magazine lead styles */

.lead font-size:1.05rem; line-height:1.6; color:#333;

.wp-block-table width:100%; border-collapse:collapse; margin:1rem 0;

.wp-block-table th, .wp-block-table td border:1px solid #e6e6e6; padding:.6rem;

Keywords & Tags to Use

- history of golf

- golf evolution

- 15th‑century Scotland golf

- links golf

- golf course design

- golf equipment history

- golf rules R&A USGA

Three Tailored Endpieces: Magazine, Academic Journal, Social Post

Magazine (feature close)

Pair archival quotes, designer sketches, and a player’s short account to leave readers with an image-perhaps an early morning tee at St Andrews-showing tradition and change coexisting on the course.

Academic Journal (abstract summary)

Synthesize evidence and methodology: archival analysis, cartographic evidence of early courses, and material culture studies of clubs and balls. Provide citations to primary sources and a suggested bibliography.

social Post (short shareable copy)

From sand dunes to stadium lights: discover how golf whent from Scottish links to global greens.Swipe for a 60‑second timeline and three facts you didn’t know about the Haskell ball, Old Tom morris, and augusta.

Further Reading and Resources

- Club archives (St Andrews, Royal & Ancient histories)

- USGA Museum and historical rulebook digitizations

- Scholarly articles on landscape architecture and sport history

- Practical guides on SEO and analytics (Google Search console, Analytics Academy)

If you’d like, I can: deliver the entire article in a strictly scholarly citation format for a journal; create a 1,200‑word magazine narrative with pull quotes and image suggestions; or write 10 social posts (Twitter/X/Instagram) from the material above. Which tone and format do you want me to expand into a full deliverable?