Introduction

Learning the essentials of a reliable golf swing is a recurring struggle for newcomers and a primary topic in coaching, biomechanics, and motor‑learning research. Mistakes in foundational areas-grip, stance, posture, alignment, ball position, swing plane and sequencing, tempo, and weight transfer-frequently appear together and amplify each other, yielding erratic ball trajectories, shorter distance, higher scores, and greater potential for repetitive‑strain injuries. Although there is an abundance of beginner guidance online and in print, much of it is fragmented, anecdotal, or lacks strong empirical backing. That uncertainty makes it tough for coaches and self‑learners to choose interventions that consistently produce both short‑term gains and lasting skill retention.

This review condenses findings from biomechanical studies,motor‑learning experiments,and applied coaching reports to (1) highlight the eight most common performance‑limiting faults among novice golfers,(2) explain how each fault undermines swing mechanics and outcomes,and (3) offer practical,evidence‑aligned fixes-drawing on constraint‑based methods,principled feedback schedules,practice variability,and biomechanical optimization-together with drills and staged progressions. By connecting scientific principles with actionable practise, the aim is to give instructors, clinicians, and independent learners a structured, research‑driven roadmap for diagnosing problems and prescribing corrections that improve reliability, power, and enjoyment of the game.

Each subsequent section tackles one focal error, summarizes relevant empirical or applied evidence, and closes with prioritized, scalable interventions that balance immediate range improvements with durable motor learning. This guidance is intended as a robust starting point for efficient, safe skill development rather than a substitute for tailored coaching.

Grip Fundamentals and Evidence based Adjustments to Enhance Control and Prevent injury

the hands are the interface between player and club: small changes in how the club is held change wrist motion, forearm rotation, and ultimately the clubface angle at impact as well as the loads experienced by the elbow and wrist. Effective grips therefore combine consistent hand placement with an appropriate, adaptable pressure that permits hinge and release during the swing.

Teachable, measurable grip elements include the lead‑hand orientation (neutral vs.strong),the trail‑hand role (supportive vs. dominant), and the grip tension (secure yet relaxed). For many right‑handed beginners, placing the lifeline of the lead hand slightly behind the club and aligning the “V” formed by thumb and forefinger toward the right shoulder helps stabilise face control. Avoiding extreme ulnar deviation or excessive wrist extension during motion reduces compressive and shear stress on forearm tissues.

Research using kinematics and EMG suggests a moderate, consistent grip pressure allows timely release with lower peak muscle activation-clinically described around a mid‑range on subjective scales-thereby lowering lateral epicondyle loads while maintaining control. Practical cues: adopt a “relaxed but secure” hold, visually check that both “V”s appear similar on practice reps, and use video or pressure sensors where available to confirm pressure and face alignment around impact.

Low‑risk, high‑repeatability drills translate evidence into practice:

- Pressure‑calibration warmup – use a squeeze ball or simple pressure sensor to set a consistent pre‑practice tension.

- Shadow swings with a visual cue – rehearse maintaining the lead “V” through takeaway and transition.

- Grip‑fit check - measure hand span and confirm grip circumference; mismatched grips can alter wrist mechanics and joint load.

- Gradual loading plan – when changing grip, increase tempo and ball‑struck reps slowly to allow tendon adaptation.

These steps target shot dispersion and face control while reducing overload risk.

| Common Fault | Observed Sign | Evidence‑Based Correction |

|---|---|---|

| White‑knuckle hold | Elevated muscle activity; variable release | Set to moderate tension; perform squeeze‑ball reps |

| Excessively strong lead hand | Closed face / pulled starts | Reposition lead heel pad; mirror check V alignment |

| Incorrect grip size | Compensatory wrist motion; elbow discomfort | Measure hand span; fit appropriate grip; re‑test |

Integrate these corrections into short, measurable practice segments to preserve the player’s preferred swing while improving impact consistency and reducing injury risk.

Stance Stability and Lower Body Mechanics: Research Informed Strategies for Balance and Power

The lower limbs and pelvis‑to‑torso coordination supply the rotational energy that the arms and hands convert into clubhead speed. Studies using force platforms and 3‑D motion capture show that an effective stance is not immobility but a controlled channeling of ground reaction forces (GRF) through a coordinated kinetic chain. Reducing excessive lateral sway and timing variability generally yields tighter dispersion and more clubhead speed for beginners.

Mechanical targets associated with better outcomes include an appropriate stance width, moderate knee flex (~10-20°), a neutral spine angle, and an ability to coil around a supported lead leg. A shoulder‑width base tends to balance rotational freedom and torque production: too narrow restricts torque, too wide hinders turn.pressure‑mapping research shows efficient swings shift pressure from the trail foot during the backswing to the lead foot by impact, producing favorable GRF peaks and sequencing.

Drills that emphasize repeatable motor patterns rather than vague imagery include:

- Feet‑width drill: mark a shoulder‑width base and make half swings to reinforce platform geometry.

- Towel‑under‑trail‑heel: a small towel under the rear heel discourages lateral slide and promotes hip turn.

- Step‑through finish: slow swings that end by stepping forward train timing of weight transfer and balance.

- Medicine‑ball rotational tosses: develop explosive hip‑to‑torso sequencing and force application.

Use concise cues like “brace the lead leg,” “load then rotate,” and “turn against a firm base” to link drills to on‑course execution.

Pair technical practice with targeted strength, mobility and proprioceptive work. Rapid reference for common deficits and interventions:

| Observed Deficit | Evidence-Based Intervention |

|---|---|

| Excessive lateral sway | Single‑leg balance + towel‑under‑heel drill |

| Poor weight transfer | Step‑through drill + posterior‑chain strengthening |

| Limited hip rotation | Thoracic mobility work + medicine‑ball rotations |

Measure progress with short video clips, pressure‑insoles, or balance tests. A simple microcycle-two strength/mobility workouts per week targeting single‑leg stability and posterior‑chain strength, plus three 15-20 minute technical sessions emphasising slow, intentional repetitions-typically shows measurable reduction in lateral centre‑of‑pressure movement and improved lead‑side loading within 4-8 weeks when stability training precedes high‑speed swings. Adhere to the principle “stability before speed” to convert neuromuscular gains into performance.

Alignment Accuracy and Visual aids to Improve Targeting and Shot Consistency

New golfers frequently misalign their feet, hips or shoulders relative to the intended line, and they frequently enough set the clubface inconsistently. These errors stem from incorrect perceptual coding of the line‑to‑target and from skipping an explicit pre‑shot routine. The result is predictable directional bias-curved misses and systematic left/right errors-that undermines scoring and motivation. Treating alignment as a perceptual‑motor task, not just a mechanical tweak, yields faster corrections.

Simple, repeatable cues and inexpensive visual anchors are highly effective. Establish a pre‑shot routine that identifies a distant target, fixes an intermediate ground cue, then verifies body alignment. Practical drills include:

- Two‑stick alignment: one stick aimed at the target and another parallel to the toes to rehearse body aim;

- Intermediate‑point fixation: choose a 3-5 yard point in front of the ball to unify clubface and body alignment;

- Mirror/video checks: short, frequent reviews to correct habitual skew.

These steps prioritise perceptual clarity and repeatability.

External aids-alignment rods, laser pointers, marked mats-create immediate reference frames that shift attention outward to the target and make aiming more reproducible. Practices adapted from “quiet‑eye” research encourage a brief, steady fixation on a proximal point before initiating the swing; such protocols have been linked to improved accuracy in other aiming sports and can be applied transiently as scaffolds to build on‑course transfer.

Design practice sessions using motor‑learning principles to boost retention. The table below summarises a compact prescription:

| Practice Variable | Evidence-Based Proposal |

|---|---|

| Focus of attention | External (target/intermediate cue) |

| Practice schedule | variable / random practice to aid transfer |

| Feedback frequency | Reduced and summary feedback to promote self‑correction |

| Use of aids | Temporary scaffolds that are progressively faded |

quantify alignment gains with dispersion charts, measured alignment angles from video, and session logs. Phase out visual aids in stages: guided practice → unguided practice on the range → on‑course replication while monitoring retention.Combining objective measures with the player’s subjective confidence ensures alignment training improves both accuracy and the perceptual strategy needed for sustained on‑course performance.

Postural Integrity and Spinal Health During the Swing: biomechanical recommendations for Novices

Maintaining a mechanically advantageous spinal posture during the swing reduces cumulative compressive and shear stresses and supports consistent rotation.Novices often show excessive lumbar flexion, lateral bending, or forward head carriage at address and through the transition-patterns that increase low‑back pain risk and reduce rotational efficiency. A dynamic neutral lumbar curve combined with thoracic rotation produces an efficient pathway for force transfer from the legs through the trunk to the club.

Target segmental dissociation rather than rigidity. Key coaching priorities are to preserve neutral lumbar lordosis at setup, allow productive thoracic rotation to drive the shoulder turn, maintain a controlled pelvic hinge (avoid anterior tilt), and minimise lateral bend during the downswing. Cues such as “hinge from the hips, chest tall” translate complex biomechanics into reproducible actions for beginners.

combine mobility, motor control and progressive strengthening to remediate postural faults. Useful drills and exercises include:

- Thoracic mobility work – foam‑roller or seated rotation drills to increase transverse range needed for shoulder turn.

- Hip‑hinge practice – dowel feedback to reinforce pelvic mechanics and protect the lumbar spine.

- Core endurance sets – anti‑rotation and anti‑extension exercises to improve tolerance during repeated swings.

- Re‑patterning swings – slow, mirror‑guided reps and band‑resisted rotations to retrain timing without pain‑provoking loads.

use short, frequent, low‑load sessions to lock in new patterns before increasing speed or volume. The table below pairs common faults with corrective cues and micro‑drills:

| Common fault | Cue | Short Drill (1-2 min) |

|---|---|---|

| Rounded upper back / collapsed chest | “Lift the chest, long spine” | Wall posture holds with club across shoulders |

| excess lateral bend | “Center your weight, hinge at hips” | Slow swings with alignment stick to monitor lateral motion |

| Locked pelvis / limited rotation | “Turn from the ribs” | band‑resisted torso rotations |

Monitor progress with periodic mobility and strength screens and video checks. If pain, neurological symptoms, or progressive loss of function occur, refer to a sports‑medicine professional before increasing practice load. Collaboration between instructors and rehabilitation specialists produces the best outcomes by blending motor‑learning tactics with tissue‑specific conditioning to protect the spine while improving swing repeatability.

Swing Path Correction Techniques grounded in Kinematic Analysis and Practice Drills

Modern correction approaches are grounded in a kinematic view of how pelvis, thorax and upper‑limb rotations and translations create the clubhead path. Timing of rotational peaks and the spatial position of the clubhead at early downswing, mid‑downswing and impact determine path and face‑to‑path relationships. Objective tools-high‑speed video, 3‑D motion capture, or IMUs-turn guesswork into measurable variables such as clubhead path angle, hand‑arc radius, and face‑to‑path at a fixed instant (for example, 50 ms before impact), allowing coaches to diagnose whether problems are systemic (sequencing) or local (forearm/wrist timing).

Practical diagnostic thresholds help convert measurements into coaching targets. As a pragmatic rule, a clubhead path greater than +3° suggests a pronounced in‑to‑out tendency; values below −3° indicate a persistent out‑to‑in bias. Face‑to‑path discrepancies exceeding roughly ±4° commonly create strong side spin and large misses. Useful tools include launch monitors (path and face), wearable IMUs for segmental angular velocity, and slow‑motion video with reference lines-together these enable tailored interventions instead of generic cues.

- Pelvis‑thorax separation: re‑establish proximal‑to‑distal timing to control arc and delay hand release.

- Arc radius control: correct excessive flattening or steepening to address out‑to‑in or in‑to‑out patterns.

- Forearm rotation timing: synchronise supination/pronation with the desired face delivery.

- Immediate feedback: combine audible/visual ball‑flight feedback with objective readouts to speed adaptation.

The drill matrix below links single, focused exercises to clear objectives and concise coaching cues for efficient practice sessions.

| Drill | Primary Cue | Objective |

|---|---|---|

| Alignment‑stick gate | “Feel the butt through the gate” | constrain clubhead path at impact |

| Impact bag | “Compress into the bag” | Rehearse a square, compressive contact |

| Towel under armpits | “Maintain connection” | Preserve body‑arm link and proper arc |

| Low‑to‑high tempo swings | “Smooth acceleration” | Restore timing and reduce early release |

Structure practice to align with motor control principles: begin with blocked practice targeting a single kinematic goal for 10-15 minutes (highly focused reps), then shift to variable practice that simulates on‑course perturbations. Reassess objective metrics after two weeks. Start with salient external feedback during acquisition and then fade it to encourage internalisation.For durable transfer, mix short, high‑quality range sessions with on‑course simulations rather than long, unfocused practice; consider a progression criterion such as holding clubhead path within ±2° across successive sessions as an indicator of readiness to advance.

Tempo Regulation and Rhythm Training Using Objective Feedback and Metronome Based Protocols

Consistent tempo is a major contributor to repeatable contact and direction among beginners. Research shows that temporal regularity-the variability of swing duration-often predicts shot dispersion more reliably than many gross kinematic measures. Objective feedback transforms the subjective idea of “a good rhythm” into measurable variables (backswing time, downswing time, and their ratio), helping coaches target specific timing deficits and track improvements over sessions.

Accessible measurement tools range from consumer wearables to lab equipment; each has trade‑offs between affordability and precision. Typical options include:

- Wearable IMUs – record angular velocity and event timing for real‑time auditory cues.

- Launch monitors – timestamp impact and, when synchronised, provide pre‑impact tempo metrics.

- High‑speed video – allows manual extraction of event times (address, top, impact) for audit or validation.

- Force/pressure plates – measure timing of weight transfer relative to swing phases and tempo.

Metronome protocols make tempo concrete. A frequently used target is a backswing:downswing ratio near 3:1 (for example, a full‑swing backswing ≈ 900 ms and downswing ≈ 300 ms), although absolute timings should be adapted for individual anthropometry and club length.The table below offers starting BPM ranges and phase durations novices can use as initial guides and refine with measurement feedback.

| Shot Type | Metronome (BPM) | Approx. B:S:D (ms) |

|---|---|---|

| Putting (short) | 60-70 | Back 500 : Down 250 |

| Iron (mid) | 48-56 | Back 800 : Down 270 |

| Driver (full) | 40-48 | Back 900 : Down 300 |

Progress tempo training through three stages: (1) acquisition with blocked, metronome‑paced trials; (2) variability where different clubs and distances are interleaved while preserving phase ratios; (3) contextual transfer where the metronome is removed for retention trials under light pressure. For beginners, short frequent doses (15-25 minutes, 2-3 times per week) are recommended with objective criteria such as reduced standard deviation of swing time and stable or improved dispersion. Gradually fade external pacing to reach internally driven timing that meets the same benchmarks before full course return.

Optimal Ball Positioning by Club Type: Empirical Guidelines and Drill progressions

Ball position is a biomechanical requirement, not a stylistic choice: it determines where the club’s arc and the golfer’s center of mass converge at impact to produce the desired launch and contact. As club length increases and loft decreases,the effective sweet‑spot of the swing arc moves forward in the stance; shorter,higher‑lofted clubs typically place the ball more centrally or slightly back to encourage a descending strike and spin generation.

| Club Category | Ball Position (Relative to Stance) | Primary Impact Intention |

|---|---|---|

| Driver / Tee shots | Forward, inside front heel | Upward sweep – high launch, low spin |

| Fairway woods | Just forward of center | Shallow entry – slightly ascending to neutral |

| Long irons (2-4) | Center to slightly forward | Neutral to slight descending |

| Mid irons (5-7) | Center | Descending blow with shallow divot after ball |

| Short irons / wedges | center to back of center | Steep, descending strike for spin and control |

Turn these guidelines into reliable on‑course habits with progressive drills:

- Alignment‑stick baseline - lay a rod parallel to the target and place a second stick to mark where the hands align at address for consistent ball placement.

- Tee‑height sweep drill – vary tee heights for woods to practice a shallow, forward contact plane.

- Impact‑bag / towel routine - for irons, work on ball‑first, turf‑second strikes by hitting a soft bag or using a towel under the armpits to stabilise connection.

- Step‑and‑hit progression – step toward the ball before striking to exaggerate forward positions for longer clubs, then return to normal setup.

Objective feedback speeds learning: monitor launch angle, spin, carry, and smash factor along with qualitative signs like divot placement (irons: divot after ball) and shot shape. Expect fat shots and low launch if the ball is too far back; thin shots and reduced spin control if it’s too far forward.Make small (half‑inch) iterative adjustments and document the effect on launch and dispersion until the metrics and impact patterns meet the player’s goals.

Periodise ball‑position work: initial validation sessions (10-15 deliberate strikes per club), mid‑cycle scenario integration (simulate several holes using the chosen ball positions), and final transfer tests under time constraints. weekly plan example: two short, data‑driven technical sessions plus one scenario or simulator session, concentrating on the two clubs most divergent from optimal metrics. Use concise cues-“forward for long clubs, center for mids, back for wedges”-to reduce in‑round cognitive load.

Short Game Fundamentals and Evidence based Remedial exercises for Chipping and Putting

Lower scores come from dependable contact, predictable launch characteristics, and controlled speed. Chipping relies on a stable lead side, limited wrist collapse and a slightly descending strike; putting depends on a repeatable pendulum arc, consistent face control and forward roll.Motor‑learning research shows that deliberate, variable practice that isolates one element at a time-distance control, for example-combined with immediate outcome feedback, transfers to on‑course performance faster than undirected repetition.

Effective chipping drills emphasise contact mechanics and landing‑zone planning:

- Bump‑and‑run progression – start narrow, hands low to teach forward shaft lean and predictable roll; progress toward lower‑loft clubs as contact improves.

- Landing‑box drill – designate a 1-2 m target area on the green and practice landing the ball within it to balance trajectory and roll.

- Single‑contact awareness – use tees or markers to practise crisp ball‑first, turf‑second strikes to avoid skulled shots.

- Alignment‑stick pathing – place a rod outside the target line to create the desired entry and low‑point relative to the ball.

Perform 8-12 focused reps per condition with outcome feedback for consolidation.

Putting work targets face control, tempo and distance feel. Try these drills:

- Gate drill - two tees slightly wider than the putter head enforce a square face and resist wrist collapse.

- Distance ladder – make putts to progressively longer targets (e.g., 3 m, 6 m, 9 m) to refine acceleration.

- One‑hand / stroke template – alternate single‑handed putting to expose asymmetries and improve stroke symmetry.

- Tempo metronome – use a metronome or counting cadence to standardise backswing‑to‑forward‑swing timing and reduce variability.

Alternate blocked practice for technical acquisition with randomized tasks to build decision‑making under variability, consistent with retention research.

Supplement technique with prehabilitative exercises to lower injury risk and improve control. A three‑times‑weekly routine might include:

- Wrist isometrics – 3 sets of 10-15 s resisting flexion/extension to limit late wrist collapse.

- Thoracic rotations – 2-3 sets of 10 controlled reps per side to preserve trunk mobility for putting and chipping arcs.

- Scapular control holds – 3 sets of 8-12 scapular retractions to stabilise the shoulder girdle.

- Single‑leg balance with club – 2-3 sets of 20-30 s per leg to steady the chipping platform.

Increase complexity only after technical consistency to avoid reinforcing compensations.

A compact, evidence‑aligned short‑game microcycle for novices is below; alternate focus days and include brief outcome reviews after each block to accelerate error detection and adaptation.

| Drill | Duration | Primary Objective |

|---|---|---|

| Landing Box (Chipping) | 15 min | Trajectory‑to‑roll calibration |

| Gate Drill (Putting) | 10 min | Face control through impact |

| Distance Ladder | 15 min | Speed management |

| Physical Prep Circuit | 10-15 min | Stability & mobility |

For retention, build the motor pattern with blocked repetitions, then move to randomized, outcome‑driven practice to improve adaptability on the course; the motor‑learning literature supports this phased structure for rapid, transferable gains.

Q&A

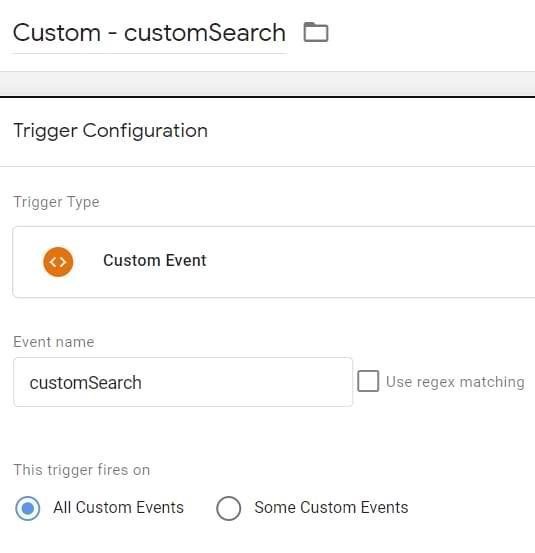

Note about search results

– The supplied web search results refer to unrelated educational services and do not contain material specific to golf technique. The Q&A below summarises evidence‑informed findings prepared to accompany this article,”Top Eight Novice Golf Errors and Evidence‑Based Remedies.”

Q1 – What are the “top eight” novice golf errors identified in the article?

– 1) Incorrect grip (hand placement and grip pressure)

– 2) Poor stance and posture (spinal angle, knee flex, athletic base)

– 3) Misalignment and poor aim (face and body aim)

– 4) Incorrect ball position

– 5) inefficient weight transfer and balance (sway, reverse pivot)

– 6) Faulty swing mechanics and plane errors (casting, early extension, steepness)

– 7) Inconsistent tempo and rhythm

– 8) under‑practiced short game/putting and deficient course management

Q2 – Why focus on these errors? what is the theoretical and empirical justification?

– These faults are common among beginners and directly affect face control, contact quality, launch conditions, and scoring. Remedies draw on three evidence domains: (a) biomechanics (kinematic/kinetic patterns of efficient swings), (b) motor‑learning science (focus of attention, feedback schedules, practice variability), and (c) applied coaching studies that show improvements when targeted drills and cues are used. Foundational frameworks include stage models of learning, deliberate practice concepts, and evidence favouring external‑focus instructions for retention.Q3 – Error 1: Incorrect grip - what is the problem and the evidence‑based remedy?

– Problem: inconsistent hand placement or excessive/uneven gripping causes variable face angles and timing issues.- Rationale: the grip determines face orientation and torque; consistency reduces degrees of freedom for novices.

- Remedies:

– Adopt a neutral or slightly strong lead‑hand reference depending on desired shot shape; use reproducible landmarks (lifeline coverage, “V” alignment).

– Teach moderate grip pressure (subjective mid‑range) to permit wrist hinge; use a towel or soft ball tension drill.

- Begin with blocked practice and visible haptic feedback (coach hand placement, rod across hands), then introduce variability.

– Progression: mirror/video checks and pressure trainers where available.

– Measurement: reduced directional scatter and improved face consistency recorded via video or launch monitor.

Q4 - Error 2: Poor stance and posture – problems and remedies?

– Problem: slumped or overly upright posture, inappropriate base width, and locked knees limit coil and disrupt swing plane.

– Remedies:

– Teach neutral spine with a hip hinge and athletic knee flex; use wall or mirror drills to internalise the hinge.

– Prescribe base width by club and assess single‑leg balance to gauge stability.

– Progress via posture holds → slow swings → full swings.

- Evidence: consistent posture supports torso rotation and reduces compensatory hand/wrist actions.

Q5 – Error 3: Misalignment and poor aim – what works to correct this?

– Problem: body lines and clubface not aligned to the intended target, causing systematic misses.

– Remedies:

– Use alignment aids immediately to create reliable reference frames.

– Teach clubface alignment first, then align the body to the selected path.

- Drills: “aim‑first” routine with an intermediate target, two‑stick alignment, and video feedback.

– Evidence: clear external reference frames improve goal‑directed aiming tasks.

Q6 – Error 4: Incorrect ball position – how to remediate?

– Problem: ball too far forward or back relative to club selection, causing thin or fat strikes and inconsistent launch.

– Remedies:

– Follow standard positioning guidelines (driver forward, mid irons centre, wedges back) and validate with markers.

– Educate on the link between ball position, low point, and shaft lean.

– make small, measured adjustments and record changes in launch and dispersion.

– Evidence: ball position shifts attack angle and low‑point location, influencing contact repeatability.

Q7 – Error 5: Inefficient weight transfer and balance – how to correct?

– Problem: lateral slide,reverse pivot,or sticking on the trail foot impede energy transfer.

– Remedies:

– Emphasise rotational loading of the trail foot in the backswing and timely transfer to the lead foot on the downswing.

– Drills: step‑through finish, feet‑together swings, medicine‑ball throws for sequencing.

– Use tempo and progressive loading to coordinate timing.

– Evidence: proximal‑to‑distal sequencing research supports these approaches for consistency.

Q8 – Error 6: Faulty swing mechanics and plane errors – practical corrections?

– Problem: casting, early extension, overly steep or flat planes reduce power and control.

– Remedies:

– Use swing‑plane references (alignment rod,mirror),gate drills,slow‑motion reps,and impact bag work.

– Emphasise external cues (“send the clubhead”) to enhance retention.

– Motor‑learning progression: blocked acquisition → variable practice for transfer.

– Evidence: biomechanical and learning studies support structured drills and external focus cues.

Q9 – Error 7: Inconsistent tempo and rhythm – how should novices address tempo?

- Problem: mismatched backswing and downswing timing causing mistimed impacts.

– remedies:

– Instil a simple pre‑shot routine and a tempo ratio (e.g., 3:1 backswing:downswing).

– Use metronome pacing, counting cues and constrained tempo drills.

– Fade external pacing as the internal rhythm stabilises.

– Evidence: temporal regularity correlates strongly with dispersion and performance stability.

Q10 – Error 8: Neglected short game/putting and poor course management – why address early?

– Problem: many beginners overemphasise full‑swing practice at the expense of scoring shots, limiting stroke reduction.

– Remedies:

– Allocate practice with an inverted pyramid (more time on short game and putting).- Teach simple, repeatable chipping and putting setups with targeted drills.- Introduce basic course‑management: play percentage shots and prioritise risk management.

– Evidence: analyses show short game and putting account for a significant share of strokes gained/lost; focused practice accelerates scoring betterment.

Q11 – What coaching and motor‑learning principles should guide remediation?

– Principles:

– Use external‑focus cues for better acquisition and retention.

- Begin with simplified tasks and increase complexity progressively.

- Start with blocked practice for novices, transition to variable practice for transfer.- Offer reduced, summary feedback to promote self‑monitoring and deliberate practice.

– References: foundational motor‑learning literature and applied coaching texts support these recommendations.

Q12 - What tools and technology are recommended for novice correction?

– Low‑cost: alignment rods, impact bag, mirror, tees, metronome, tape markers.

- Mid/high‑cost: smartphone slow‑motion, launch monitors, pressure mats, putting mats.

– Use objective tools to inform coaching rather than replace core instruction.

Q13 – How should practice time be allocated and measured for progress?

– Suggested weekly split for beginners: 40-50% short game/putting, ~30% full‑swing fundamentals, 20-30% on‑course play and decision practice.

– Track measurable metrics: contact location, dispersion, putts per round, up‑and‑down percentage, plus subjective markers (confidence, enjoyment).

– Expected timeline: consistent improvements are often measurable within 4-8 weeks of structured, deliberate practice; substantial motor changes typically require months of ongoing work.

Q14 - When should a novice seek a certified coach or healthcare professional?

– Consult a certified instructor when persistent faults do not respond to structured practice or when seeking accelerated learning.

– Seek medical advice if pain, acute symptoms, or mobility limitations impede safe practice. Combining coaching with basic physical screening lowers injury risk and improves outcomes.

Q15 – How can coaches and players maintain motivation during technical correction?

– keep sessions short,goal‑oriented and varied; include games and targets,celebrate small,objective gains,and regularly apply skills on the course to connect practice with meaningful outcomes.

Q16 – Recommended further reading and evidence sources

– Core sources in motor learning and coaching: Fitts & Posner; Ericsson on deliberate practice; Wulf on external focus effects; Schmidt & Lee on motor control.

– For applied biomechanics and golf‑specific summaries,consult up‑to‑date systematic reviews and peer‑reviewed sports‑science literature.Closing note

– The interventions summarised hear combine biomechanical insight with motor‑learning strategies and simple, low‑cost drills. Best results come from assessment‑driven coaching, short measurable practice goals, and occasional objective feedback. Tailor progressions to each learner’s physical capabilities and learning pace.

In Retrospect

this synthesis has identified eight high‑impact faults in novice golf-grip, posture/stance, alignment, ball position, swing‑plane mechanics, tempo, weight transfer, and short‑game neglect-and paired each with empirically supported corrective approaches. Across biomechanics, motor learning, and coaching science, the consensus favours simplified outcome‑directed instructions, external‑focus cues, progressive variable practice, well‑timed feedback, and selective use of video and measurement to individualise instruction.

For practitioners,the practical takeaway is clear: prioritise a small set of high‑leverage fixes,structure practice into short measurable blocks,and monitor objective indicators (clubhead speed,impact location,balance metrics,shot outcomes). Such an assessment‑driven approach produces more durable gains than layering numerous simultaneous technical changes. From a research standpoint, longer, ecologically valid trials and studies that explore individual differences (age, prior motor skill, physical capacity) would refine personalised instruction models.

In closing,combining targeted assessment,principled intervention and iterative measurement provides a realistic pathway for turning common novice faults into dependable skill. Aligning coaching with the best available evidence supports better technique, improved scoring, and increased enjoyment of the game.

lower Your Score: 8 Common Novice Golf Errors with proven Corrections

New golfers often plateau because of predictable, fixable faults. Below are eight high-impact mistakes beginners make, why they happen, and research-informed, practical fixes and drills you can apply on the range and course today. Keywords to watch: beginner golf, novice golfers, fix swing, golf mistakes, lower your score, grip, stance, putting, course management.

Mistake 1 – Weak or Incorrect Grip

Why it matters

A poor grip leads to inconsistent clubface control – the primary cause of slices, hooks, and weak shots. Simple grip changes yield immediate improvements in ball flight and feel.

How to fix it (Proven Corrections)

- Neutral grip check: Place the club in your lead hand so you can see two to three knuckles when looking down. Rotate the trail hand so the “V” formed by thumb and forefinger points between your chin and trail shoulder.

- Grip pressure: Use the 4/10 rule – grip with a light-to-medium pressure (about 4 out of 10). Too tight restricts wrist hinge and reduces clubhead speed.

- Drill – gloveless swings: Make 20 slow swings without a glove to feel the correct hand placement and pressure.Then repeat with the glove, matching the same feel.

- Outcome: More consistent clubface orientation at impact; immediate reduction in errant ball flight.

Mistake 2 – Poor Stance and Alignment

Why it matters

Misalignment sends shots off target before the swing even starts. Many beginners aim the body toward the target incorrectly or set thier feet too narrowly/widely for the intended shot.

How to fix it (Proven Corrections)

- Alignment routine: Pick a small intermediate target 3-6 feet ahead (a blade of grass or tee). Square your clubface to that target first, then align feet, hips, and shoulders parallel to the intended line.

- Stance width: Use shoulder-width for irons, slightly wider for woods and driver. weight should be balanced on the balls of the feet, not heels or toes.

- drill – Club-on-the-ground: Lay two clubs on the ground: one pointing at the target (clubface), the other parallel to your feet. Practice setting up until this looks natural.

- Outcome: Straighter shots and better shot shaping predictability.

Mistake 3 – Overactive Hands and Casting at Impact

Why it matters

Casting (releasing the wrists too early) and overactive hands rob you of power, consistent loft, and control. This typically results in thin or fat shots and inconsistent distance.

How to fix it (proven Corrections)

- Maintain wrist lag: Practice swings focusing on keeping the angle between club shaft and lead forearm until just before impact.

- drill – Towel under armpits: Hit short shots (50-80 yards) with a towel tucked under both armpits to promote connected motion and reduce hand-dominant releases.

- tempo training: Use a 3:1 takeaway to downswing rhythm (three counts back, one forward) to promote sequence over hand flicks.

- Outcome: Better compression, more distance control, fewer thin/fat misses.

Mistake 4 – Poor Weight Transfer and Balance

Why it matters

Power and accuracy depend on efficient weight transfer from trail to lead side. Beginners often hang back on their trail foot or sway, causing weak strike and loss of control.

How to fix it (Proven Corrections)

- Finish position focus: Strive to finish with most weight on lead foot, hips rotated toward the target, and a balanced pose.

- Drill – Step-thru drill: Make half swings and step the trail foot forward through the shot to feel forward weight shift. Repeat slowly to ingrain motion.

- Use video: Record slow-motion swings to monitor hip rotation and weight shift patterns.

- Outcome: Increased ball speed, tighter dispersion, and fewer skulled or bladed shots.

Mistake 5 – Incorrect ball Position

Why it matters

Ball too far back or forward disrupts swing arc and loft at impact-leading to net launch angle and distance inconsistencies.

How to fix it (Proven Corrections)

- General rules: For irons, position the ball central or slightly forward of center. For driver, place the ball opposite the inside of the lead heel.

- Check lie angle: Shorter clubs require slightly back ball positions and narrower stances. Adjust using impact tape or launch monitor feedback.

- Drill – Ladder practice: Hit incremental shots moving the ball position a clubhead width forward/back to see the flight change; note where you achieve clean, preferred flight.

- Outcome: More consistent contact and predictable distance control.

Mistake 6 – Neglecting the Short Game (Chipping and Pitching)

Why it matters

Lowering scores is more about proximity to the hole than pure driving distance. Many beginners spend too much time on the driver and neglect wedges and putting.

How to fix it (Proven Corrections)

- Technique basics: Use a narrow stance, weight slightly forward, hands ahead at impact, and a quiet lower body for chips. For pitches, widen stance, increase wrist hinge, and use more shoulder turn.

- Drills – Landing spot drill: Place a towel or coin as a landing target 10-30 feet from the hole. Practice landing the ball consistently on that spot using different clubs.

- Practice split: Allocate 40% of practice time to short game and putting, 30% to full swing, 20% to course management/strategy, and 10% to fitness/warm-up.

- Outcome: Lower scores through better up-and-down conversion rates.

mistake 7 – Poor Putting Fundamentals and Readings

Why it matters

Putting is where most shots are saved or lost. Misreading the green and inconsistent setup/tempo multiply mistakes into higher scores.

How to fix it (Proven Corrections)

- Setup essentials: Eyes over the ball (or slightly inside), a square putter face, and a pendulum stroke with minimal wrist action.

- Green reading method: Read from behind the ball, then from the low side and the hole’s side to triangulate.Look for slope, grain, and wind effects.

- Drills – Gate drill: Place two tees slightly wider than your putter head and practice stroking through the gate to improve path and face control.

- Routine: Use a pre-putt routine (visualize line,two practice strokes,commit) to reduce indecision and nerves.

- Outcome: More one-putts and fewer three-putts.

Mistake 8 – Overlooking Course Management and Mental game

Why it matters

Beginners often try to hit hero shots instead of playing smart golf. aggressive choices, poor club selection, and lack of pre-shot routine increase mistakes.

How to fix it (Proven Corrections)

- Play to your strengths: Pick targets and clubs that you can consistently execute-par is a good score on many holes.

- Risk-reward assessment: If hazards force risky recovery shots, take the safer route and give yourself a putt or chip you can make.

- Mental routine: Develop a simple pre-shot routine (visualize, alignment check, breathe) to reduce tension and maintain focus.

- Practice under pressure: Include pressure elements in practice (e.g., must make 5 of 8 chips in a row) to simulate on-course stress.

- Outcome: Fewer penalty strokes, smarter decisions, and steadier scoring.

Swift Reference Table – Errors and Fixes

| Mistake | Immediate Fix | Drill |

|---|---|---|

| Grip | Neutral hand placement, 4/10 pressure | gloveless swings (20) |

| Alignment | clubface to intermediate target | Clubs-on-ground |

| Casting | Keep wrist lag; tempo | Towel under armpits |

| Weight Transfer | Finish on lead foot | Step-through drill |

| Ball Position | Club-specific placement | Ladder practice |

| Short Game | Hands ahead, quiet feet | Landing spot drill |

| Putting | Eyes over ball, pendulum stroke | Gate drill |

| Course Management | Play smart, routine | Pressure sets |

4-Week Practice Plan (Beginner-Friendly)

Follow this weekly structure and you’ll see rapid improvement in fundamentals and on-course results.

- week 1 – Fundamentals: 3 sessions: Grip, stance, alignment, basic tempo. end each session with 30 short chips and 30 putts.

- Week 2 - Short Game Focus: 2 range sessions (wedges & chipping),1 putting session. Begin landing-spot drills and gate drills.

- Week 3 - On-course Management: Play 9 holes focusing on conservative club choices and pre-shot routine. Back at range, practice weight transfer and lag drills.

- Week 4 – Pressure & Play: Simulated pressure drills (countdown to make shots), then a full 18 focused on applying decisions and short game recovery.

benefits & Practical Tips

- Lower scores quickly: Correcting high-leverage fundamentals (grip, alignment, ball position) produces outsized score improvement for novice golfers.

- Enduring progress: Swap “fix everything” thinking for a prioritized approach-solve the biggest error first and measure improvement.

- Use tech wisely: A launch monitor or even simple slow-motion video helps identify what the eye misses (e.g., early release, improper ball position).

- Fitness & warm-up: A simple dynamic warm-up (leg swings, torso rotations, shoulder circles) improves range of motion and reduces injury risk.

- Patience: According to expert learning research,short,focused practice sessions (20-40 minutes) multiple times per week beat rare marathon sessions.

Case Study – A Typical Novice Turnaround (Short)

“Mark,” a new golfer who struggled to break 110, used a 6-week plan focusing first on grip and alignment, then short game and putting. By week 6 his average score fell 12 strokes-driven mostly by an improved short game and fewer penalty shots after adopting conservative course-management tactics. The pattern is common: small technical fixes combined with better decision-making produce fast score reduction.

Notes on the Term “Beginner”

Definitions vary, but academic and dictionary sources commonly define a beginner as a person just starting to learn an activity or skill. For golfing context, “beginner” generally applies to players developing fundamental swing mechanics, course awareness, and consistent short-game skills. (See standard definitions of “beginner” in lexical resources.)

Actionable next Steps

- Pick one high-leverage issue from the above list and focus on it for 2 weeks.

- Implement one drill per practice session and track outcomes (miss patterns, distance, up-and-down percentage).

- Book an occasional lesson with a certified instructor to reinforce correct mechanics early-this prevents bad habits from becoming entrenched.