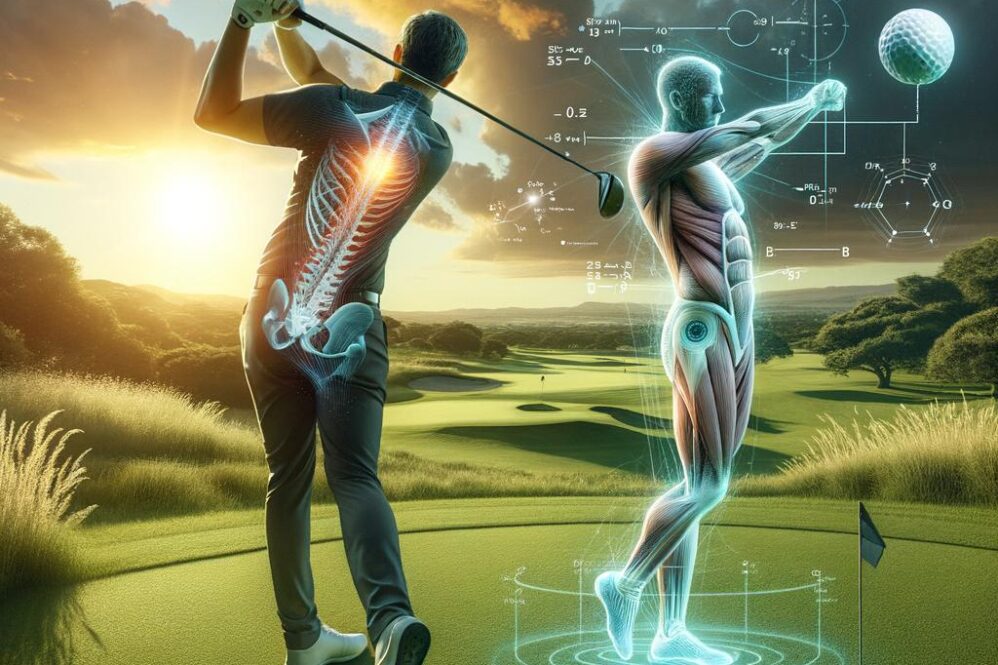

The golf swing represents a highly coordinated, multi-joint motor task that integrates rapid segmental rotations, precise timing, and graded force production to achieve repeatable ball-strike outcomes.Its biomechanical complexity-characterized by three-dimensional kinematics, time-varying kinetics, and finely tuned neuromuscular activation patterns-renders the swing both a model system for studying human movement and a locus of common musculoskeletal injury. Understanding the mechanistic relationships among segmental motion, joint loading, and muscle coordination is therefore essential for optimizing performance, informing evidence-based coaching, and mitigating injury risk across recreational and elite populations.

This article systematically examines contemporary research on golf-swing biomechanics, synthesizing findings from motion-capture kinematic analyses, force-plate and club-acceleration kinetics, electromyographic investigations of neuromuscular dynamics, and computational modeling studies. emphasis is placed on causal links between technique variables (e.g., sequencing, pelvis-thorax separation, wrist mechanics), external and internal loading patterns, and outcome measures such as ball velocity, dispersion, and injury markers. Methodological considerations-including measurement fidelity, subject sampling, and analytic approaches-are highlighted to contextualize reported effects and identify sources of interstudy heterogeneity.

By integrating empirical evidence with applied considerations for coaching and rehabilitation, the review aims to translate biomechanical insights into actionable guidance for technique refinement and load management. The subsequent sections address: (1) kinematic signatures of effective swings and common technical faults; (2) kinetic determinants of performance and joint loading; (3) neuromuscular strategies underpinning timing and stability; (4) injury mechanisms and preventive interventions; and (5) gaps in the literature and priorities for future research. Together, these analyses provide a framework for clinicians, coaches, and researchers seeking to apply rigorous biomechanical principles to improve performance while reducing injury risk.

Kinematic Sequencing and Segmental Coordination in the golf Swing Assessment and Corrective Strategies

Proximal-to-distal sequencing underpins efficient energy transfer in the golf swing: a timed cascade from pelvis rotation to thorax, upper arm, forearm, and finally the clubhead yields maximal clubhead speed with controlled impact. Kinematic analysis prioritizes positional and temporal variables – joint angles, angular velocities, and their time-to-peak – rather than forces (the domain of kinetics/dynamics). Key signatures of an effective sequence include a clear temporal order of peak angular velocities (pelvis → trunk → lead arm → club),a maintained separation (X‑factor) between hips and shoulders through the transition,and preservation of segmental lag in the downswing to optimize release. Deviations (early arm speed, late pelvis rotation, or loss of trunk rotation) predict reduced ball speed and inconsistent strike patterns even when external strength is sufficient.

Assessment integrates qualitative observation with quantitative kinematic metrics to specify the locus and timing of breakdowns. Commonly measured variables include:

- Time-to-peak angular velocity for pelvis, trunk, and lead arm

- Intersegmental separation angles (hip-shoulder X‑factor)

- Segmental lag magnitude and release timing

- Clubhead path and face angle at impact

- center-of-mass transfer and weight‑shift timing

Practical tools range from high-speed video and 2D/3D motion capture to IMU sensors and validated smartphone apps; selection depends on the required resolution and the athlete’s skill level.

When corrective strategies are prescribed they should be specific to the kinematic fault and progressively load motor control, mobility, and sequencing. The table below summarizes concise corrective mappings for common sequencing faults; coaches should combine these with objective reassessment after 4-8 weeks of focused training.

| Observed Fault | Kinematic Signature | Corrective Drill / Cue |

|---|---|---|

| Early arm acceleration | Premature peak in lead arm velocity | “Hold the angle” kettlebell downswing; trunk-first downswing drill |

| Late pelvis rotation | Pelvis peak velocity lagging trunk | Seated hip-turn sets; resisted band hip-rotation swings |

| Loss of X‑factor | Reduced hip-shoulder separation at top | Thoracic rotation mobility + top-of-backswing pause with chest‑lead cues |

Implementation should follow an iterative assessment-intervention cycle with predefined objective targets (e.g., restore pelvis peak velocity to occur within 40-60 ms before trunk peak) and measurable outcomes (clubhead speed, dispersion, impact location). emphasize neuromuscular drills that reinforce timing (metronome/tempo work), mobility routines that enable separation (thoracic and hip mobility), and load‑management to avoid compensatory patterns. combine short‑term drills with context-rich transfer practice (progressive speed, varied lies, and fatigue conditions) so that improved kinematic sequencing and segmental coordination become robust under competitive constraints.

Ground Reaction Forces and Lower Limb Mechanics Optimization for Power Generation and postural Stability

Ground reaction forces (GRFs) constitute the mechanical interface between the golfer and the playing surface; they include vertical, anteroposterior and mediolateral components that together determine the external moments applied to the body. By resolving GRFs into directional vectors and expressing magnitudes relative to body weight, clinicians and coaches can quantify how effectively lower-limb impulses are converted into angular momentum about the pelvis and thorax. The timed coupling of peak vertical GRF with pelvic rotation is notably critical: when vertical force peaks are synchronized with rapid hip-shoulder separation, intersegmental power transfer is maximized and ball velocity increases. Conceptually, the ground functions as the immobile reaction surface that enables generation of these propulsive impulses.

Optimization of lower-limb mechanics requires coordinated sequencing of hip, knee and ankle actions with active modulation of leg stiffness. Effective power generation typically relies on early eccentric loading of the trail leg, rapid concentric extension from the hips and knees, and controlled pronation-supination of the subtalar complex to tune transfer of force through the foot. Electromyographic and biomechanical evidence supports emphasis on the following intervention targets:

- Eccentric preloading: controlled trail-leg deceleration in late backswing to store elastic energy.

- Explosive hip extension: prioritized over isolated knee drive for efficient proximal power production.

- Variable leg stiffness: modulated across stance phases to balance energy return and shock attenuation.

- Foot coupling: preserving a stable forefoot pivot during downswing to direct GRF vectors optimally.

Postural stability is maintained through dynamic control of the center of pressure (COP) within the base of support; excessive COP excursions or premature lateral unloading of the trail foot increase the likelihood of loss of balance and inefficient energy transfer. Quantitative COP trajectory analysis during the downswing reveals common error patterns: premature lateral shift reduces effective frontal-plane torque, whereas excessive medial drift of the lead foot increases valgus loading at the knee. Rehabilitation and conditioning programs should thus combine balance-challenging tasks with sport-specific loading patterns to concurrently enhance stability and force production.

Objective assessment and targeted drills accelerate adaptation. Force-plate metrics and wearable inertial sensors provide repeatable measures of timing, magnitude and direction of GRFs; these data inform individualized cues and exercise progressions. Example target ranges (illustrative) for an efficient driver swing are shown below to guide monitoring and training priorities.

| Phase | Peak vGRF (×BW) | COP displacement (cm) |

|---|---|---|

| Late Backswing (trail) | 0.9-1.2 | 2-4 (medial) |

| downswing (transfer) | 1.6-2.4 | 6-10 (lateral → lead) |

| Impact | 1.8-2.6 | 3-6 (stabilized) |

Pelvic Rotation and Thoracic Mobility Balancing Mobility,Stability,and Injury Risk for Consistent Ball Striking

Optimal sequencing of axial rotation begins with adequate rotation through the pelvis followed by dissociation at the thoracic spine.Effective energy transfer from the lower body to the clubhead depends on a coordinated proximal-to-distal timing: hip turn generates ground reaction forces and torque, the lumbar region stores and transmits load, and the thorax provides the final rotational conduit to the shoulders and arms. When pelvis rotation is restricted or premature, compensatory over-rotation or lateral flexion in the thorax often occurs, degrading strike consistency and increasing shear loads on the lumbar spine.

Balancing segmental mobility with joint stability requires targeted assessment and intervention.Key clinical considerations include:

- Pelvic mobility: adequate transverse plane rotation and hip internal/external rotation range;

- Thoracic extension/rotation: sufficient multi-planar motion to allow shoulder turn without upper lumbar compensation;

- Core and pelvic floor integrity: the ability to tolerate intra‑abdominal pressure while maintaining lumbopelvic control.

Clinical resources such as the Mayo Clinic Health System emphasize pelvic floor health across populations – note that pregnancy and pelvic disorders can alter pelvic mechanics and should be considered when prescribing swing adaptations or strengthening programs.

Practical training strategies must be evidence-informed and individualized. Progressive loading that concurrently develops hip rotational capacity, thoracic mobility, and lumbopelvic stability reduces transfer inefficiencies:

- mobility drills (e.g., thoracic rotations on foam roller, hip cars) to restore segmental range;

- stability progressions (e.g., anti‑rotation chops, deadbug variations) to maintain control during dynamic rotations;

- pelvic floor and breath integration to manage intra‑abdominal pressure during high‑velocity swings.

These elements should be sequenced from isolated control to golf‑specific dynamic tasks to avoid overload and minimize injury risk.

Below is a concise comparative framework for programming emphasis based on common presentations:

| Presentation | Primary Focus | Risk if Unaddressed |

|---|---|---|

| Limited hip rotation | Increase hip mobility, load bearing drills | Compensatory lumbar rotation; inconsistent contact |

| Thoracic stiffness | Thoracic mobility, scapular control | Early arm casting; reduced clubhead speed |

| Pelvic floor/continence concerns | Pelvic floor rehab, breath‑timing | Symptom exacerbation, avoidance of intensity |

Employing this balanced approach – restoring requisite mobility, reinforcing joint stability, and attending to pelvic health – fosters reproducible kinematics and reduces the cumulative tissue load that predisposes golfers to both acute and chronic injury.

Upper extremity Kinetics and Clubface Control Technical Adjustments to Improve accuracy and Clubhead Speed

Upper-limb contribution to ball flight is governed by coordinated action of the scapulothoracic and glenohumeral joints, the elbow hinge, and the wrist/forearm complex. Precise orientation of the clubface at impact is a product not only of distal wrist and hand motion but of proximal stability and timing: the shoulder complex positions the arm and stores elastic energy,the elbow modulates lever length and release timing,and the wrist/forearm convert rotational energy into clubhead angular velocity. Empirical kinematic analyses show that small changes in lead-wrist dorsiflexion or forearm pronation within the final 100 ms before impact produce measurable deviations in face angle and shot dispersion, while preserved proximal-to-distal sequencing maximizes peak clubhead speed without compromising face control.

Technical adjustments should thus address both stability and dynamic control. Targeted cues and drills emphasize efficient energy transfer and consistent face orientation at impact. Recommended elements include:

- Grip pressure: maintain a moderate, consistent hold (subjective 3-5/10) to allow rapid wrist release while preventing face twist.

- Wrist hinge and lag: create and sustain lag through the downswing to increase clubhead velocity while using the lead wrist to manage face angle.

- forearm rotation: practice controlled pronation through impact to square the face rather than abrupt supination or collapse.

- Scapular stability: drills that promote a stable shoulder girdle (e.g., slow, resisted swing reps) to reduce distal compensations.

| Metric | Typical target | Functional Effect |

|---|---|---|

| Lead wrist at impact | Slight dorsiflexion / near-neutral | Consistent loft & reduced spin variability |

| Forearm pronation rate | Controlled through impact window | Improved face squaring and accuracy |

| Peak clubhead angular velocity | Maximize via preserved lag | Greater distance with maintained dispersion |

For coaches and biomechanists implementing these adjustments, adopt a phased, feedback-driven program: quantify baseline kinematics (video, inertial sensors, or motion capture), apply isolated technical cues with immediate augmented feedback, and progress to integrated, variable practice to promote robust motor patterns. Emphasize proximal strength and neuromuscular control-rotator cuff endurance, scapular stabilizers, and forearm pronator/supinator conditioning-to reduce compensatory wrist break and face misalignment under load. prioritize small, repeatable changes and objective monitoring (launch monitor dispersion metrics, impact tape, and angular-velocity profiles) to balance gains in clubhead speed with preserved or improved accuracy.

Temporal Dynamics and Swing Tempo Analysis Using Timing Interventions to Reduce performance Variability

Temporal structure of the swing exerts a primary control on inter-shot variability: the relative duration of backswing and downswing, the timing of the transition, and the synchronization of segmental sequencing together define a golfer’s temporal signature. quantitatively, this signature is characterized by **tempo** (absolute durations), **cadence** (relative durations, e.g., backswing:downswing ratios), and **variability** (standard deviation or coefficient of variation across trials). High-frequency analysis of clubhead speed and segment angular velocity time-series reveals systematic phase relationships (lead-lag intervals) that predict impact consistency more robustly than peak velocities alone. Consequently, interventions that target temporal coordination-rather than only force production-are more effective at reducing performance variability in both lab and field settings.

timing-focused interventions should be selected and sequenced according to motor-learning principles to maximize transfer. Effective modalities include:

- Auditory metronome pacing to stabilize intra-swing rythm and provide an external timing scaffold;

- Explicit pause drills at transition to recalibrate the downswing onset and refine sequencing;

- Variable tempo practice (systematic perturbation around a target tempo) to enhance adaptability;

- External-focus protocols that emphasize ball-target relationships while maintaining a prescribed cadence to promote automaticity.

These interventions reduce cognitive load by converting a high-dimensional temporal problem into a low-dimensional timing constraint, enabling the nervous system to exploit consistent phase relationships between trunk, arm, and club.

Analytical approaches combine time-domain and frequency-domain metrics to quantify intervention effects.Typical analyses include cross-correlation of segmental velocity traces, spectral peak detection of cadence, and computation of trial-to-trial coefficient of variation (CV) for key events (transition time, impact epoch). Example empirical outcomes from controlled training blocks are summarized below to illustrate expected magnitudes of change.

| Tempo Ratio (BS:DS) | Observed Effect | CV Reduction (approx.) |

|---|---|---|

| 3:1 (metronome) | improved impact timing, stable clubface angle | 12-18% |

| 2.5:1 (pause at transition) | Enhanced downswing sequencing | 15-22% |

| Variable ±10% | Greater adaptability under perturbation | 10-15% |

These values are indicative; practitioners should use individualized baseline assessments to set realistic targets and monitor progression.

Implementation requires a phased program: baseline temporal profiling, targeted intervention blocks with objective monitoring, and transfer sessions under simulated on-course conditions. Measurement devices such as IMUs, high-speed video, and launch monitors facilitate repeatable, timestamped event detection; compute metrics like CV, phase lag, and spectral peak prominence weekly to evaluate retention. For most golfers, a 4-8 week focused timing intervention yields measurable reductions in temporal variability and concomitant improvements in dispersion metrics; continued variability-focused maintenance (e.g., brief metronome sessions or transition pause cues) helps sustain gains. Emphasize that the goal is not a singular ideal tempo for all players, but a **consistent, individual tempo** that reliably produces efficient kinematic sequencing and repeatable impact conditions.

Objective Measurement Protocols Using Motion Capture and Wearable Sensors for Reliable Biomechanical evaluation

Objectivity in biomechanical evaluation requires that measurement protocols be founded on reproducible, fact-based procedures rather than subjective appraisal - consistent with dictionary definitions of “objective” as being based on real facts and free from personal bias. To achieve this, protocols must codify sensor selection, placement, calibration and synchronization so that kinematic, kinetic and neuromuscular outputs are directly comparable across sessions, systems and research groups.Core protocol principles include:

- Standardization of marker/IMU placement and coordinate-system definitions.

- Adequate temporal resolution to capture the rapid accelerations of the golf swing.

- System synchronization (optical, IMU, force plate, EMG) within millisecond precision.

- obvious reporting of calibration, filtering and event-detection methods to support replication and meta-analysis.

Selection of modality and sampling parameters must reflect the mechanical bandwidth of the swing. Typical recommended settings used in reliable evaluation are summarized below; these should be adapted to specific study aims and validated against a reference system when possible.

| Modality | Typical placement | Recommended sampling |

|---|---|---|

| Optical motion capture | Full-body marker set + club markers | 200-500 Hz |

| Inertial measurement units (IMUs) | Pelvis, thorax, lead wrist, trail wrist, club shaft | 200-1000 Hz |

| Force plates / pressure insoles | Under feet or insole sensors | 500-2000 Hz (1000 Hz optimal for impact transients) |

| Surface EMG | Relevant prime movers (glute, erector spinae, obliques, forearm) | 1000-2000 Hz |

Data processing decisions directly influence outcome reliability. Use objective, documented procedures for drift removal, coordinate alignment and filtering: e.g., identify cut-off frequencies by residual or spectral analysis rather than arbitrary choices, employ zero-lag Butterworth filters for kinematic time series (typical low-pass ranges ~6-20 Hz for joint angles in high-speed sport tasks) and higher cut-offs for force and EMG as dictated by signal content. Event detection (address,top of backswing,impact) should combine kinematic and kinetic triggers to reduce ambiguity. Extracted outcome variables should span multiple domains,such as:

- Kinematics: segment and joint angles,angular velocities,X‑factor and sequencing latencies

- Kinetics: GRF peaks,loading rates,inter-limb impulse,inverse dynamics moments

- Neuromuscular: EMG onset/offset,activation amplitude normalized to MVC,co-contraction indices

- Derived coordination metrics: continuous relative phase,temporal sequencing,and transfer of momentum to the club

Reliability must be quantified and reported using accepted statistics (e.g., ICC for relative reliability, SEM and minimal detectable change (MDC) for absolute reliability), and protocols should include intra- and inter-session repeatability trials. A minimal reporting checklist improves transparency and cross-study comparability: device model and firmware, sampling rates, filter types/cut-offs and justification, marker/IMU placement diagrams, synchronization method, calibration procedures, number of repetitions, and reliability statistics. account for practical constraints (environmental magnetic interference for IMUs, marker occlusion for optical systems, and sensor drift) and describe mitigation strategies so that each measurement can be judged in the context of its documented validity and reliability.

Translating Biomechanical Insights into Practice Structured Drills, Feedback Modalities, and Periodized Training Recommendations

To operationalize biomechanical principles into training, coaches should design drills that isolate and then integrate critical segments of the kinematic sequence. Emphasize drills that target **pelvic rotation**, **thoracic turn**, and **wrist lag** independently before combining them into full‑swing patterns. Representative practice progressions include a) slow‑motion sequencing to reinforce timing, b) impact‑focused punches to refine clubface control, and c) resisted rotational drills to develop torque without loss of tempo. These targeted exercises accelerate motor learning by constraining specific degrees of freedom and promoting reproducible movement solutions consistent with biomechanical optimality.

Effective learning relies on multimodal feedback that translates complex biomechanical data into actionable cues. Use a mix of **extrinsic** (video,launch monitor metrics,force‑plate summaries) and **intrinsic** (verbal cues,proprioceptive constraints) feedback to scaffold skill acquisition. Recommended modalities:

- High‑speed video for kinematic sequencing and joint angle review.

- Launch monitors for objective ball‑flight and club‑head metrics (SMASH, spin, launch).

- Wearable IMUs / sensors to track segmental timing and angular velocities in real time.

Combine immediate, high‑frequency feedback during early learning with summary and bandwidth feedback as athletes advance to encourage self‑monitoring and retention.

Periodization should align biomechanical advancement with physiological conditioning and competitive demands. A simplified macrocycle can be organized into four phases-Planning, Strength, Power/Speed, and Integration/Peaking-each with discrete objectives and representative interventions.

| Phase | Primary Objective | Example Focus |

|---|---|---|

| Preparation | Mobility & motor patterning | Segmental drills, corrective mobility |

| Strength | Develop force capacity | Rotational strength, multi‑joint lifts |

| Power/Speed | Rate of force development | Med ball throws, ballistic swings |

| Integration | Transfer to performance | On‑course simulations, tempo work |

Period lengths should be individualized based on training age, injury history, and upcoming competition schedule; load and complexity increase progressively while preserving the movement patterns validated by biomechanical assessment.

Operational guidelines for session design and monitoring create accountability and optimize adaptations. Structure sessions around a warm‑up that primes **neuromuscular sequencing**, a main block targeting the phase‑appropriate quality (e.g.,power outputs),and a short transfer block emphasizing accuracy under constraint. Track objective metrics to guide progression:

- Club‑head speed and ball velocity

- Pelvis‑shoulder separation and timing of peak angular velocities

- Ground reaction force profiles and rate of force development

Implement regular re‑assessments (every 4-8 weeks) and coordinate with physiotherapists and strength coaches to mitigate injury risk while preserving technique fidelity. This multidisciplinary, metric‑driven approach ensures biomechanical insights are translated into measurable, sustainable performance gains.

Q&A

Preface

The following Q&A is intended as an academic, professional companion to an article on “Analyzing Biomechanics and Technique of the Golf Swing.” It synthesizes contemporary biomechanical concepts (kinematics, kinetics, and neuromuscular dynamics) and translates them into practical guidance for evidence‑based technique refinement and injury mitigation.Note: the web search results provided with the request did not include peer‑reviewed biomechanical literature specific to the golf swing; the Q&A below therefore summarizes widely accepted biomechanical principles and applied research themes rather than citing a single source.

Q1: What are the primary goals of a biomechanical analysis of the golf swing?

A1: The primary goals are to (1) describe the motion (kinematics) and forces/moments (kinetics) acting during the swing, (2) characterize muscle activation and motor control strategies (neuromuscular dynamics), (3) identify mechanical determinants of performance (e.g., clubhead speed, ball launch parameters), and (4) detect movement patterns that increase injury risk.The ultimate aim is to inform technique modifications, conditioning, and clinical interventions grounded in quantitative evidence.

Q2: How is the golf swing commonly subdivided for analysis?

A2: The swing is typically divided into sequential phases: address/setup, backswing (early and late), transition/top of backswing, downswing (early and late), impact, and follow‑through/finish. These phases facilitate temporal alignment of kinematic, kinetic, and EMG data and help identify phase‑specific deficits or compensations.

Q3: Which kinematic variables are most informative for performance assessment?

A3: Key kinematic variables include segmental orientations and angular displacements (pelvis, thorax, shoulders, arms, wrists), intersegmental separation (commonly “X‑factor” or pelvis‑torso separation), peak angular velocities (pelvis, torso, proximal-to-distal sequencing), timing of peak velocities, clubhead path and face angle, and joint angles at critical instants (e.g., wrist **** at top, hip and knee flexion). Temporal coordination (onset and peak timing) is as informative as magnitudes.

Q4: What kinetic measures should be collected and interpreted?

A4: Essential kinetic measures are ground reaction forces (GRFs) and their center‑of‑pressure, joint reaction forces and internal/external moments derived from inverse dynamics, net segmental power and intersegmental power transfer, and external work done on the club. These indicate how the golfer uses the ground and proximal segments to generate clubhead speed and control.

Q5: How do kinematics and kinetics interact to produce clubhead speed?

A5: Efficient generation of clubhead speed relies on coordinated proximal‑to‑distal sequencing: rotational energy created by the pelvis and torso is transmitted across segments and amplified by distal segments (shoulder → arm → wrist → club). Kinetically, GRFs provide a base to generate axial rotation and produce reaction moments; net joint moments and segmental power transfers convert rotation into linear and angular velocity of the clubhead. timing and smooth transfer are critical-magnitude without correct timing reduces effectiveness.

Q6: What is the “X‑factor” and why is it vital?

A6: the X‑factor denotes the relative rotational separation between the pelvis and thorax at or near the top of the backswing (thorax rotation minus pelvis rotation). Greater separation is associated with increased storage of elastic energy and higher potential for angular velocity in the downswing,contributing to higher clubhead speed.however, excessive separation or abrupt release can increase lumbar loading and injury risk.

Q7: What neuromuscular dynamics are relevant in a golf swing?

A7: Relevant dynamics include timing and amplitude of muscle activations (EMG) of trunk rotators, hip extensors, gluteals, quadriceps, hamstrings, scapular stabilizers, and forearm/wrist musculature; feedforward motor planning to preposition segments; reflexive and feedback control for impact perturbations; and muscle stiffness modulation for energy transfer and accuracy. Sequenced, well‑timed activations underpin efficient kinematic chaining.

Q8: Which measurement technologies are standard in golf‑swing biomechanics?

A8: Common tools are 3D optical motion capture (marker‑based),inertial measurement units (IMUs),high‑speed video,force platforms for GRFs,electromyography (surface EMG) for muscle activity,instrumented clubs and clubhead trackers (launch monitors),and instrumented treadmills or pressure mats for COP data. Inverse dynamics requires synchronized kinematics and kinetics plus anthropometrics.

Q9: What analytical methods are used to interpret data?

A9: Analyses commonly include time‑series kinematic/kinetic plotting,calculation of joint angles/velocities/accelerations,inverse dynamics to compute internal moments and powers,principal component analysis or functional data analysis for movement patterns,statistical parametric mapping (SPM) for continuous data inference,and correlation/regression models to link biomechanical variables with performance outcomes.

Q10: What movement patterns commonly correlate with higher clubhead speed?

A10: Correlates include larger and well‑timed pelvis and torso rotation (with appropriate X‑factor),early and rapid trunk rotation initiation in the downswing,effective use of ground reaction forces (lateral weight shift and vertical impulse),proximal‑to‑distal sequencing of peak angular velocities,and preservation of wrist lag into the late downswing. Coordination and timing are consistently more predictive than single maximal joint values.

Q11: What technique features are associated with increased injury risk?

A11: Injury risk is associated with excessive or abrupt lumbar spine rotation combined with high compression/shear (e.g., extreme X‑factor with poor pelvic control), repeated high torsional loads without adequate conditioning, hyperextension at the wrists at impact, excessive shoulder abduction/internal rotation loading, and poor lower‑limb stability that transmits abnormal loads proximally. Repetitive submaximal loading and sudden technical changes can also precipitate injury.

Q12: How can analysis guide individualized technique refinement?

A12: Analysis identifies the limiting factors for an individual-mobility, sequencing, strength, timing, or balance. Such as,reduced pelvis rotation with normal torso rotation suggests limited hip mobility or fear of weight shift; late or weak pelvic acceleration may point to inadequate hip extensor strength. Interventions should target the specific deficit: mobility drills, neuromuscular re‑training for sequencing, strength/power conditioning, or technique cues to modify timing.

Q13: What conditioning strategies reduce injury risk while enhancing performance?

A13: A balanced program includes:

– Mobility: thoracic rotation and hip internal/external rotation.

– Stability: lumbopelvic control and scapular stabilization.

– Strength: hip extensors,trunk rotators,and shoulder girdle.

– Power and rate of force development (RFD): ballistic rotational and lower‑limb drills.

– Eccentric control: to manage decelerations during follow‑through.

Progressive load management, adequate recovery, and addressing movement asymmetries are essential.

Q14: What role do coaching cues play and how should they be chosen?

A14: Cues should be individualized and aligned with biomechanical deficits. External cues (e.g., “rotate the shoulders through impact”) frequently enough produce better immediate motor performance than complex internal instructions. Use objective measures (video,launch monitor,force) to validate the effect of a cue and prescribe drills that reinforce desired timing and sequencing.

Q15: How should clinicians and researchers assess injury mechanisms?

A15: Combine biomechanical assessment (kinematics, kinetics, EMG) with clinical evaluation (history, strength, mobility, pain provocation tests). Longitudinal monitoring of training load, swing changes, and symptom evolution helps determine causality.Modeling (e.g., finite element or musculoskeletal simulations) can estimate tissue‑level stresses when direct measurement is impossible.

Q16: What are practical assessment metrics to include in a clinical or coaching battery?

A16: Practical metrics: clubhead speed and ball launch parameters (carry, spin), pelvis and thorax rotation ranges, timing of peak angular velocities, X‑factor magnitude and separation velocity, peak GRF magnitudes and lateral shift timing, COP excursion, key joint ROM (hip, thoracic rotation), trunk and hip strength measures, and simple EMG patterns when available. Consistency and reproducibility matter as much as absolute values.

Q17: What limitations should readers be aware of when interpreting swing analyses?

A17: Limitations include lab versus field differences (performance may change on course), variance across club types and shot contexts, inter‑individual variability (anthropometry, adaptability, coaching history), measurement errors (skin movement artifacts, IMU drift), and cross‑sectional designs that preclude causal inference. Single metrics should not be overinterpreted without context.

Q18: How can technology (IMUs, launch monitors) be integrated for field‑based analysis?

A18: IMUs and launch monitors offer practical, portable data collection. Combine clubhead and ball data from a launch monitor with IMU‑derived segmental angles and force‑plate proxies (e.g., pressure mats) to approximate kinematics and kinetics. Ensure sensor calibration, synchronization protocols, and validation against lab gold standards where possible.

Q19: What are key recommendations for future research?

A19: Important directions include longitudinal studies linking biomechanical measures to injury incidence, finer characterization of neuromuscular control during fatigue and under competitive stress, multi‑scale modeling to estimate tissue loads, individualized intervention trials targeting sequencing deficits, and development of robust field‑usable assessment protocols validated against laboratory standards.

Q20: How should practitioners translate biomechanical findings into practice?

A20: Use a structured approach: assess baseline biomechanics and clinical status; identify objective, prioritized deficits; implement targeted interventions (technical drills, conditioning, mobility); monitor response with objective metrics (video, launch monitor, strength tests); iterate adjustments; and manage training load and recovery. Emphasize reproducible drills and measurable progress rather than prescriptive global changes.

Q21: Are there special considerations for different populations (e.g., junior, older, injured golfers)?

A21: Yes. Juniors require growth‑appropriate conditioning and technique that account for maturation.Older golfers may prioritize mobility and eccentric strength to maintain swing speed while protecting joints. Injured golfers need pain‑informed modifications, graded return‑to‑play protocols, and close monitoring of loading and technique changes to avoid compensatory overload.

Q22: What constitutes a high‑quality biomechanical report for a golfer?

A22: A robust report includes: participant/context details (club, ball, shot intent), methods (sampling rates, sensors, model assumptions), kinematic and kinetic time‑series aligned to key events, key outcome metrics with normative or prior session comparisons, interpretation linking deficits to possible causes, recommended targeted interventions, and a plan for follow‑up assessment.

Q23: How should findings be communicated to athletes and coaches?

A23: Communicate clearly and pragmatically: prioritize 2-3 actionable points, use visualizations (key video frames, plots) to show the issue and the goal, demonstrate simple drills and cues, and provide measurable targets and timelines. Use objective metrics to show progress and maintain buy‑in.Closing summary

Biomechanical analysis of the golf swing integrates kinematics, kinetics, and neuromuscular dynamics to explain how performance is produced and how injury risk arises. The most effective interventions are individualized, evidence‑based, and target the specific mechanical or neuromuscular deficit identified by objective assessment. Future progress depends on longitudinal studies, improved field metrics, and translational research bridging laboratory insights to coachable, safe techniques.

a biomechanically grounded analysis of the golf swing synthesizes kinematic description, kinetic causation, and neuromuscular control to create a coherent framework for both performance enhancement and injury prevention. by situating swing mechanics within the broader discipline of biomechanics-the scientific study of movement-coaches, clinicians, and researchers can move beyond anecdote toward reproducible, measurable interventions that objectively target swing inefficiencies and harmful loading patterns. Kinematic metrics (e.g., segmental velocities, timing, and sequencing) describe what occurs; kinetic measures (e.g., ground-reaction forces, joint moments, and power transfer) explain why performance outcomes emerge; and neuromuscular analyses (e.g., muscle activation timing, coordination strategies, and fatigue effects) reveal the control processes that implement and constrain those mechanics.Practically, this integrative perspective supports evidence-based technique refinement: individualized assessments should guide targeted motor learning, strength and conditioning, and equipment choices to optimize energy transfer while minimizing injurious loads-particularly at the lumbar spine, shoulder, and elbow. Advances in motion capture, wearable sensors, and computational modeling now permit more ecologically valid, longitudinal monitoring of the swing, enabling practitioners to quantify adaptation to training and to detect early signs of maladaptive mechanics.

Looking forward, the field would benefit from larger cohort and longitudinal studies that link specific biomechanical signatures to performance trajectories and injury incidence, as well as from interdisciplinary collaboration that unites biomechanics, neuroscience, sports medicine, and coaching science. Standardized protocols and outcome measures will be essential to translate laboratory insights into scalable, field-ready interventions. Ultimately,applying rigorous biomechanical principles to the golf swing offers a pathway to safer,more effective technique that respects the complex interaction of anatomy,physics,and motor control inherent in high-level sport.

Analyzing Biomechanics and Technique of the Golf Swing

What “analyse” means in golf biomechanics

The word analyze (American English) or analyse (British English) means to examine methodically by separating into parts and studying their interrelations. In the context of the golf swing, analysis breaks the motion into measurable pieces – grip, posture, sequencing, rotation, and impact – to improve power, accuracy, and repeatability.

Core components of an optimized golf swing

every repeatable golf technique rests on a few fundamental elements. Addressing these with biomechanical awareness helps golfers turn practice into measurable improvement.

- Grip mechanics – influences clubface control and wrist action at release.

- stance and posture – establishes balance, spine angle, and hip mobility needed for rotation.

- Backswing and shoulder turn – stores potential energy and sets swing plane.

- Downswing sequencing – correct kinematic sequence (hips → torso → arms → club) creates efficient power transfer.

- Impact mechanics – clubhead speed, attack angle, and face alignment determine launch and spin.

- tempo and timing – consistent rhythm regulates repeatability and avoids early release.

Biomechanical principles every golfer should know

Understanding the underlying biomechanics helps coaches and players diagnose issues more reliably than subjective feel alone.

Kinematics vs. kinetics

- Kinematics: motion variables – position, velocity, acceleration of body segments and the club (swing path, rotation angles).

- Kinetics: forces and torques – ground reaction forces, joint moments, and how they generate clubhead speed.

Sequencing: the kinetic chain

An efficient golf swing follows a proximal-to-distal sequence: the hips initiate the downswing, followed by torso rotation, then arm acceleration and finally wrist release. Proper sequencing maximizes energy transfer and reduces stress on joints.

Ground reaction forces (GRF)

Power begins at the feet. GRF sensors show how players shift weight and push into the ground to create torque and vertical force that translate into clubhead speed.

Rotation and separation

The separation between hip rotation and shoulder rotation (commonly called “X-factor”) contributes to stored elastic energy. Excessive or insufficient separation both create inefficiencies or injury risk.

Clubface control and impact mechanics

Impact is where biomechanics meets ball flight. Key variables:

- Clubhead speed – primary determinant of ball speed and distance.

- Face angle at impact - governs direction; small face errors produce large misses.

- Attack angle – positive for drivers (launch), negative for irons (compression).

- Loft and dynamic loft – combined with club speed and spin produce launch angle and spin rate.

Motion-capture and measurement tools

Modern analysis blends technology with coaching instinct. Common tools used to analyze golf biomechanics:

- high-speed video – affordable, accessible, great for swing plane and timing.

- Launch monitors (TrackMan, FlightScope) - measure ball speed, launch angle, spin rate, attack angle, and club path.

- imus and inertial sensors – measure segment rotation and angular velocity in real settings.

- Force plates – capture ground reaction forces and weight-shift timing.

- 3D motion capture – gold standard for research-level kinematic detail (joint angles, sequencing).

Key metrics to track (and target ranges)

Below is a short reference table of common performance and biomechanical metrics with typical targets for amateur-to-advanced players. Use this as a starting point – individual goals will vary by body type, age, and equipment.

| Metric | What it tells you | Typical target |

|---|---|---|

| Clubhead speed (driver) | Potential ball speed/distance | 80-120+ mph (amateur → elite) |

| Ball speed | How efficient impact is (smash factor) | 1.45-1.50 (driver range) |

| attack angle | Positive for max driver launch | +1° to +5° (driver) |

| X-factor (shoulder-hip separation) | Stored rotational energy | 20°-40° (individually variable) |

Common swing faults, biomechanical causes, and fixes

Below are frequent problems seen in players, their biomechanical roots, and practical corrections.

- Slice (open face at impact)

- biomechanics: clubface open relative to path; early extension or overactive lead wrist.

- Fixes: strengthen grip slightly,drill inside-out path with alignment stick,practice impact bag hits to learn square face feel.

- Hook (closed face)

- Biomechanics: early release, over-rotated forearms, or inside path with face closed.

- Fixes: slow tempo, pause at transition, use visual alignment of face at impact in slow motion video.

- Fat shots (hitting ground before ball)

- Biomechanics: reverse spine angle,early weight shift,or poor attack angle.

- fixes: ball position adjustment, maintain spine tilt during downswing, practice soft hands through impact.

Practical drills and training protocol

use drills that address the measurable variable you’re tracking.Below are focused drills that map directly to biomechanical objectives.

Drills for sequencing and power

- Step drill: take a narrow setup, step into the ball with the lead foot during downswing to promote hip lead.

- Medicine ball rotational throws: improves explosive hip-to-shoulder transfer and core power.

- Swing with resistance band: trains delayed release and builds strength in the posterior chain.

Drills for clubface control

- Impact bag: teaches square face feel and proper wrist position at impact.

- Alignment rod path drill: set two rods to create the ideal swing plane corridor to groove the path.

- Slow-motion video feedback: review impact frame to check face and path alignment.

tempo and timing

- Count-based rhythm: 1-2 or 3-1 patterns (backswing-transition-impact) to internalize consistent timing.

- Metronome or music tempo: maintain the same backswing/downswing ratio across clubs.

How to structure an analysis-based practice session

Turn data into progress with a repeatable session plan that integrates measurement, drills, and feedback.

- Warm-up and mobility (10-15 minutes): dynamic stretches, thoracic rotation, hip mobility.

- Baseline measurement (10 minutes): record swings on video and capture a few shots with a launch monitor.

- Focus drill block (20-30 minutes): pick one biomechanical target (e.g., sequencing) and perform 3-4 drills with short sets.

- Measured integration (15 minutes): hit 20-30 shots with the same club, tracking metrics and aiming for consistency.

- Reflection and homework (5 minutes): note 2-3 practice goals and a drill to repeat between sessions.

video and data capture checklist

- Camera angles: down-the-line, face-on, and a 45° 3D-like viewpoint for context.

- Frame rate: use 240 fps or higher for clearer impact analysis when possible.

- launch monitor settings: ensure ball and club data are calibrated and club type is correct.

- Force plates/pressure mats: synchronize timing with video if available to link GRF to kinematics.

case studies: real-world examples

Case Study A – Increasing driver distance through sequencing

A 42-year-old amateur had 92 mph driver clubhead speed and an early arm-dominant release. after 6 weeks focusing on hip lead drills, medicine ball throws, and guided weight-shift practice, his clubhead speed rose to 99 mph and average carry increased ~18-25 yards. Motion-capture showed improved pelvis angular velocity and delayed wrist release (greater lag), raising smash factor slightly.

Case Study B - Fixing a persistent slice with data

A mid-handicap player averaged 20% offline drives to the right.Video and launch monitor analysis showed an out-to-in path and 6° open face at impact.Interventions: neutral-to-strong grip, alignment rod path drill, and 2 weeks of impact bag work. The result: path reduced toward neutral, face at impact closer to square, and dispersion tightened by ~40%.

Common questions about biomechanics and technique

How much should I rely on technology?

Technology gives objective feedback but should complement good coaching and feel. Use data to confirm patterns and validate changes rather than dictate every move.

Can biomechanics reduce injury risk?

Yes. Optimized sequencing and reduced compensatory motions lower joint stress. Improving mobility and strength in a targeted way protects the lower back, elbows, and shoulders.

How quickly will I see results?

Small measurable improvements can appear in weeks (tempo, face control). Larger changes to sequencing or mobility can take months. use incremental goals and consistent feedback loops.

Frist-hand coaching tips (practical, field-tested)

- Record one baseline swing per week and compare using a consistent setup – minor differences reveal trends.

- Prioritize one or two measurable objectives per practice session to avoid overload.

- Use drills that recreate on-course conditions - practice transfer matters as much as technique itself.

- Work on mobility before mechanics: increased thoracic rotation and hip mobility unlock better technique with less effort.

Meta tips: include target keywords like “golf swing”, “golf biomechanics”, “clubface control”, “swing sequencing”, and “launch monitor” naturally in headings and content to support SEO. Use structured data and alt text on all video/images and publish a short video of the impact frame for higher engagement and SERP visibility.