The web search results supplied with this request relate to unrelated messaging applications (WhatsApp) and do not provide domain-specific literature on golf biomechanics. Proceeding on that basis, the following is an academically framed introduction for an article entitled “Biomechanical Analysis of the Golf Swing.”

Introduction

The golf swing is a complex, high-velocity athletic action that demands precise coordination of multisegmental kinematics, timed kinetic impulses, and finely tuned neuromuscular control. Understanding the swing through a biomechanical lens is essential not only for optimizing performance-maximizing clubhead speed, launch conditions, and shot repeatability-but also for mitigating injury risk in the lumbar spine, shoulder, elbow, and wrist, wich frequently result from cumulative loading and suboptimal technique. Contemporary biomechanical inquiry synthesizes observations across scales, from whole-body segmental sequencing and ground-reaction force production to muscle activation patterns and joint loading, thereby offering an integrated framework for evidence-based coaching and clinical practice.

Kinematic analyses characterize spatiotemporal trajectories and angular velocities of body segments and the club, revealing critical features such as sequencing (proximal-to-distal transfer), axial rotation (the X-factor), and temporal coordination between pelvis, trunk, and upper limb. Kinetic approaches quantify the forces and moments that cause and result from motion-ground reaction forces, joint moments, and energy transfer between segments-illuminating how players generate and dissipate mechanical work during the swing. Neuromuscular investigations, employing electromyography and perturbation paradigms, disclose the timing, magnitude, and co-contraction strategies of prime movers and stabilizers that underlie both efficient power generation and joint protection. Integrating these domains enables a mechanistic understanding of trade-offs between performance and injury susceptibility and helps distinguish technique variations that reflect individual anthropometry, mobility, and skill level.

This review synthesizes current evidence from kinematic, kinetic, and neuromuscular studies to construct a cohesive model of the golf swing, identify biomechanical markers associated with optimal performance and common injury mechanisms, and translate these insights into pragmatic recommendations for technique refinement, training, and rehabilitation.We first summarize measurement methodologies and analytic frameworks used in contemporary research,then evaluate empirical findings across swing phases and player populations,and finally propose an applied framework for clinicians and coaches that emphasizes individualized,evidence-based interventions to enhance performance while minimizing injury risk.

Theoretical Framework and Scope of Biomechanical Analysis of the Golf Swing

The conceptual basis rests on an integrative, multi-scale model that synthesizes **kinematic**, **kinetic**, and **neuromuscular** perspectives to describe swing behaviour as a coordinated whole-body task. Foundational principles include proximal-to-distal sequencing,conservation and transfer of angular momentum,and the role of impulse in ball launch characteristics. This framework treats the swing as an emergent outcome of interacting subsystems (skeletal, muscular, neural, and equipment interfaces), enabling explicit hypotheses about how alterations in technique or training manifest in measurable performance and tissue loads.

Analytical constructs are explicitly delineated to guide both measurement and interpretation. Core constructs include:

- Kinematics – segmental and club trajectories, joint angles, angular velocities (high-resolution motion capture).

- Kinetics – joint moments, ground reaction forces, intersegmental forces (force plates, inverse dynamics).

- Neuromuscular dynamics – timing, amplitude, and coordination of muscle activation (EMG; neural control models).

- Contextual constraints – equipment, environmental factors, and task constraints that modulate strategy.

- Injury mechanisms – repetitive loading patterns, peak tissue strains, and asymmetries linked to risk.

These constructs form a reproducible vocabulary for hypothesis testing and technique refinement.

To operationalize the framework across scales, the following concise mapping is used:

| Scale | Primary Measures | Typical Instruments |

|---|---|---|

| Segmental | angular velocity, phase timing | Optical IMUs |

| Joint | Moments, ROM | Inverse dynamics, force platforms |

| Whole-body | CoM trajectory, energy flow | Motion capture, force plate arrays |

This condensed schema facilitates selection of appropriate tools and statistical models for targeted research questions.

methodological clarity is emphasized: **assumptions** (rigid-body segments, negligible soft-tissue artefact), **limitations** (lab-to-field transferability, sampling bias), and choices in signal processing (filtering, normalization) must be stated a priori. Analytical approaches draw from both deterministic inverse dynamics and stochastic motor-control models; nonlinear time-series and machine-learning methods complement customary statistics when addressing coordination variability or prediction of injury risk. Reproducibility demands standardized reporting of acquisition rates, model parameters, and normalization procedures.

The intended scope spans performance optimization, injury prevention, equipment interaction studies, and population-specific adaptations (elite vs recreational; junior vs master golfers). Translational aims require iterative cycles of model refinement, field validation, and targeted intervention testing, grounded in **evidence-based** interpretation of kinematic/kinetic/neuromuscular findings. Ultimately, the framework prioritizes targeted, measurable technique modifications that balance performance gains with reduction of cumulative tissue load.

Kinematic Patterns Across Swing Phases and Practical Technique Implications

Phase-specific kinematic signatures are evident when the swing is decomposed into address, backswing, transition, downswing, impact, and follow-through. At address, the athlete establishes the kinematic baseline-spine tilt, pelvic orientation, and grip geometry-that constrains subsequent joint excursions. During the backswing, coordinated increases in thoracic rotation and contralateral shoulder elevation create the pre-stretch required for elastic recoil; typical amateur-to-elite differences manifest as magnitude and timing of thorax-pelvis separation. These observable markers provide objective targets for technical coaching as they reflect underlying segmental ranges of motion and intersegmental timing rather than isolated muscular effort.

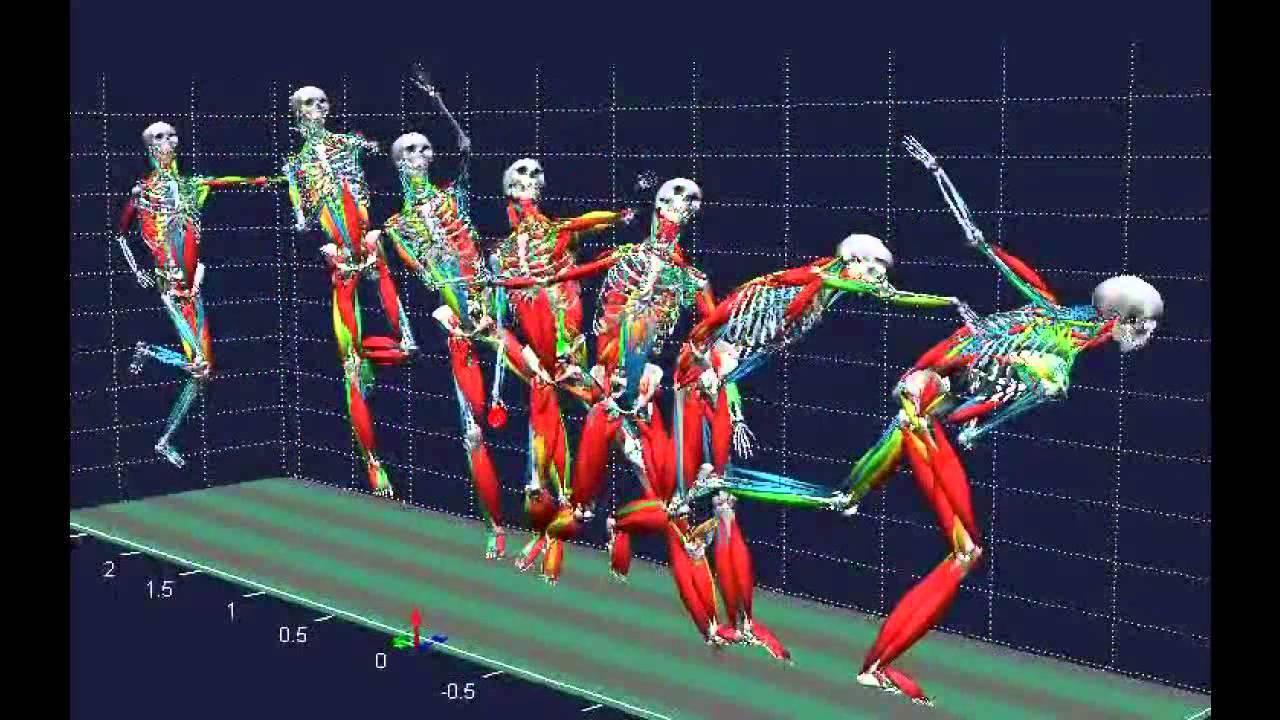

Sequencing and timing during transition and downswing determine mechanical efficiency. Effective swings exhibit a proximal-to-distal sequencing: early downswing activation of the pelvis and hips precedes trunk rotation, which in turn precedes arm acceleration and club release. This pattern maximizes angular velocity transfer through the kinetic chain and reduces dissipative counter-movements. Deviations-such as early upper-body collapse or premature arm release-produce characteristic kinematic signatures (reduced X‑factor stretch, late peak clubhead speed) that correlate with loss of distance and directional dispersion.

Impact and follow‑through kinematics reveal the culmination of prior sequencing and the golfer’s capacity to stabilize the strike. Peak clubhead speed typically occurs at or just prior to ball contact while the pelvis and trunk are decelerating, indicating prosperous energy transfer to the implement. Center-of-mass translation, ground reaction force timing, and lead‑leg bracing at impact modulate clubface orientation and effective loft. Consistent impact kinematics-stable spine angle,controlled wrist release,and balanced follow‑through-are strong predictors of reproducible ball flight in both distance and accuracy.

- Coil maintainance: preserve thorax-pelvis separation through a controlled shoulder turn rather than thoracic collapse.

- Proximal initiation drills: emphasize hip‑first downswing with medicine‑ball throws and step‑through progressions.

- Impact stabilization: use impact tape and slow‑motion video to reinforce forward weight transfer and lead‑leg bracing.

- Tempo regulation: metronome or count drills to reproduce desirable sequencing and reduce timing variability.

| Phase | Key Kinematic marker | Practical Cue |

|---|---|---|

| Backswing | Thorax rotation magnitude | “Turn chest under roof” |

| Transition | Pelvic lead initiation | “Start with hips” |

| Impact | Spine angle stability | “Hold your tilt” |

Individualization and injury considerations must guide technical prescriptions derived from kinematic analysis. Mobility limits (thoracic extension, hip internal rotation), prior injury, and asymmetries will alter feasible kinematic patterns; therefore, coaching interventions should prioritize safe ranges that preserve sequencing rather than enforcing a single template. Progressive conditioning-rotational strength, hip and thoracic mobility, and eccentric control-supports the kinematic targets described above, improving both performance reproducibility and musculoskeletal resilience.

Kinetic Drivers of ball Speed and Accuracy: Ground Reaction Forces and Segmental Torques

Ground interaction is the primary source of external mechanical power in the swing: vertical and horizontal components of the **ground reaction force (GRF)** generate impulse that is transformed into rotational and translational motion of the body-club system. Peak vertical GRF contributes to effective load transfer through the kinetic chain, while the horizontal (mediolateral and anteroposterior) components create the shear and braking forces that enable rotational acceleration. Two kinetic descriptors-**impulse** (force × time) and **rate of force progress (RFD)**-are strong predictors of potential clubhead speed because they determine how quickly and how much momentum can be supplied to the pelvis and thorax prior to arm and wrist release.

Intersegmental torque production and transfer govern the translation of GRF into clubhead velocity. A coordinated sequence of **pelvic rotation torque → thoracic torque → shoulder-arm moments → wrist/hand torques** (proximal‑to‑distal sequencing) maximizes energy flow while minimizing dissipative interactions between segments. Joint moments at the hips and lumbopelvic complex establish the rotational base; the trunk generates large axial torque, and the shoulder and forearm provide fine‑tuned torques that accelerate the club and control face orientation. the magnitude and timing of these torques-rather than isolated peak values-determine how effectively kinetic energy is conserved and focused at the clubhead.

Accuracy is shaped by both the magnitude and the neuromechanical control of torques acting on the distal segments. Small variations in wrist and forearm torque near impact alter shaft bending and face rotation,producing lateral and angular dispersion of ball flight. Maintaining a stable **center of pressure (COP)** under the feet and modulating mediolateral GRF reduces unnecessary translational motion of the torso that would or else magnify distal torque variability.Thus, precision depends on consistent GRF timing, controlled rotational torques, and the ability to dampen undesired degrees of freedom in the wrist‑shaft complex promptly prior to impact.

Practical kinetic targets for training and measurement focus on a concise set of reproducible metrics:

- Peak vertical GRF – indicator of available load for rotation

- Horizontal propulsive/braking forces – timing for weight transfer

- RFD of lower limb – speed of force application

- peak pelvic and thoracic torque – proximal power generators

- Timing indices (torque onset to release) – sequencing quality

Monitoring and training these variables improves both speed and shot‑to‑shot consistency by targeting the kinetic processes that produce and regulate clubhead energy.

| Metric | Relevance | Training/Measurement |

|---|---|---|

| Peak GRF | Power reservoir for rotation | Force‑plate testing; plyometrics |

| RFD (lower limb) | Rate of momentum transfer | Contrast training; explosive squats |

| Pelvic torque | Primary rotational driver | Rotational medicine‑ball throws |

| Wrist torque control | Face stability at impact | Speed‑controlled swing drills |

Measurement using synchronized **force plates**,inertial sensors,and biomechanical modeling allows practitioners to quantify deficits and prescribe targeted interventions; concurrently,progressive overload of rotational strength and neuromuscular timing drills reduces injury risk by distributing loads across segments rather than concentrating excessive shear or flexion moments at the lumbar spine.

Neuromuscular Control, Motor Coordination, and Timing strategies for Consistent Performance

Neuromuscular control in the golf swing is characterized by the integration of feedforward motor planning and rapid feedback corrections that together produce reproducible kinematic patterns under variable conditions. Skilled performers show anticipatory postural adjustments-pre-activation of stabilizing trunk and hip musculature-that create a stable base for distal acceleration. electromyographic studies indicate that temporal ordering (which muscle turns on first), relative amplitude, and co-contraction levels are as crucial as peak force for producing efficient energy transfer from pelvis to hands. Emphasizing timing of low-level tonic activity in stabilizers reduces unwanted degrees of freedom without sacrificing the mobility required for high clubhead speed.

Motor coordination in the swing relies on reliable intersegmental sequencing and intermuscular synergies that simplify control demands.Coaches and biomechanists should monitor a small set of phase markers that index coordination quality:

- Pelvis rotation onset (feedforward initiation)

- Trunk-shoulder separation (X-factor timing)

- Lead wrist un-cocking (release timing)

- Clubhead acceleration peak relative to the midline

These markers map directly onto corrective strategies-e.g., increasing proximal stiffness to improve distal timing or adjusting downswing sequencing to restore proximal-to-distal energy transfer.

Training interventions that target timing should combine temporal constraint drills with neuromuscular feedback. Use metronome-guided tempo progressions and EMG or inertial-sensor biofeedback to make phase transitions explicit. The table below summarizes representative muscle activation windows during an effective downswing as a practical reference for clinicians and coaches (values are illustrative relative to downswing onset = 0%):

| Muscle Group | Activation Window | Functional Role |

|---|---|---|

| Gluteus maximus | 0-30% | Pelvic drive, stability |

| External obliques | 10-50% | Trunk separation, rotational torque |

| Pectoralis major | 40-80% | Acceleration of torso and arms |

| Forearm flexors/extensors | 60-100% | Grip modulation, release control |

apply progressive overload by manipulating tempo, complexity, and fatigue to re-shape these windows without compromising sequencing.

Consistency emerges from controlled variability: allow exploration of redundant movement solutions while constraining critical timing relationships. Excessively constrained practice that eliminates kinematic variability can undermine adaptability on-course,whereas unguided variability delays the convergence on efficient synergies. Use practice schedules that alternate blocked and random tasks, provide summary feedback after trials, and emphasize outcome-based goals to encourage self-association of timing patterns. Monitor intra-session variability of timing markers as an objective metric of learning progression.

For durable performance and injury mitigation, integrate neuromuscular conditioning with technical work. Prioritize eccentric strength and rate-of-force development in the lead arm and trunk decelerators, and schedule sensorimotor sessions to maintain anticipatory activation patterns under fatigue. Practical checkpoints for programming include:

- Pre-shot routine that cues consistent tempo

- Weekly sensorimotor drill with biofeedback (2-3×)

- Fatigue screen based on timing drift in core markers

These measures preserve intersegmental timing, reduce injurious loading during deceleration, and promote reproducible, high-performing swings across contexts.

Musculoskeletal Loading, Common Injury Mechanisms, and Evidence Based Prevention Strategies

Peak musculoskeletal loads during the swing are characterized by rapid multiplanar accelerations that produce high **axial rotation moments**, combined **compressive** and **shear** forces at the lumbopelvic junction, and impulsive forces transmitted through the distal upper extremity at ball impact. Quantitative analyses show that peak lumbar compression and torsion frequently enough coincide with late downswing and follow-through, when trunk angular velocity and ground reaction forces reach their maxima.These loading patterns place particular demand on passive spinal structures, lumbopelvic stabilizers, the glenohumeral complex, and the wrist extensors, making a mechanistic link between swing dynamics and common overuse injuries.

Common clinical presentations reflect these biomechanical stressors and can be attributed to identifiable mechanisms:

- Low back pain: repetitive trunk rotation under load with insufficient eccentric control of the obliques and multifidus, leading to discal and facet overload.

- Medial/lateral epicondylalgia: repeated high-velocity wrist flexion/extension and grip forces causing tendinopathic changes at the elbow.

- Wrist and distal radius injuries: high-impact shear at ball contact, especially with early wrist release or poor swing plane.

- Rotator cuff and AC-joint pathology: excessive horizontal abduction/adduction and late deceleration demands on the shoulder complex.

- Hip and groin strains: abrupt force dissipation during weight transfer and restricted hip rotation mobility.

These mechanisms are supported by kinematic and kinetic studies linking specific swing faults to tissue-specific overload.

Prevention strategies with empirical support emphasize a combined approach targeting **technique optimization**, **physical capacity**, and **workload management**. Key interventions include:

- Technique modification: reduce early wrist release, encourage coordinated pelvis-to-shoulder sequencing to lower peak lumbar torsion.

- Strength and motor control: progressive eccentric and rotational strengthening of trunk and shoulder stabilizers to improve deceleration capacity.

- Mobility and tissue preparation: targeted hip internal rotation and thoracic extension mobilization to redistribute rotational demand.

- Load management: structured practice dose with planned recovery and monitoring of high-volume periods (e.g., tournament play).

These components are most effective when individualized to the golfer’s deficit profile and integrated by a multidisciplinary team.

Objective screening and rehabilitative progression should align with the identified biomechanical faults. Functional tests (e.g., single-leg balance with trunk rotation, seated resisted trunk rotation, shoulder IR/ER strength ratios) inform targeted programming. The following compact reference table maps common injuries to typical biomechanical contributors and primary preventive exercises, designed for rapid use by clinicians and coaches:

| Injury | Typical Fault | Primary Preventive Exercise |

|---|---|---|

| Low back pain | Excess lumbar rotation under load | Pallof press + rotary core eccentrics |

| Tennis/elbow | Repetitive high wrist torque | Eccentric wrist extensor program |

| Shoulder impingement | Late deceleration, poor scapular control | scapular stabilizer and rotator cuff strengthening |

For implementation, prioritize a hierarchy: first restore **movement quality** (technique and thoracic/hip mobility), then build **capacity** (strength, power, eccentric control), and finally manage **exposure** (practice volume, intensity). Use objective metrics-clubhead speed, ground reaction force symmetry, wearable-derived swing counts-to guide periodization and return-to-play decisions. Regular re-assessment of movement patterns and progressive loading benchmarks reduces recurrence risk and enhances the reproducibility of efficient, low-risk swings.

Assessment Methodologies and Measurement Tools for Field and Laboratory Evaluation

Laboratory-grade evaluation affords high-fidelity quantification of kinematics,kinetics,and neuromuscular activity through integrated systems,whereas field-based approaches prioritize ecological validity and accessibility. Selecting an assessment strategy requires explicit alignment between the research or coaching question (e.g., swing sequencing, joint loading, muscle activation timing) and the measurement characteristics (accuracy, sampling rate, portability). Reliability and validity must be considered a priori: laboratory systems typically yield superior spatial and temporal resolution, but repeatability in applied settings depends on standardized protocols, sensor placement consistency, and environmental control.

Kinematic capture modalities vary in complexity and suitability. Optical marker-based motion capture systems (e.g., passive/active camera arrays) remain the reference standard for joint center estimation and three-dimensional segment kinematics, while markerless algorithms offer pragmatic solutions for large-scale or in-field workflows. Inertial measurement units (IMUs) and high-speed video provide scalable alternatives for on-course assessment. Practical considerations include:

- Sampling frequency: ≥200 Hz for high-velocity segments like clubhead and distal segment motion;

- Soft-tissue artifact: mitigation via cluster markers, rigid mounts, or sensor fusion;

- Calibration: static and functional trials to define segment coordinate systems.

Markerless approaches reduce setup time but demand rigorous validation against marker-based references when used to infer joint kinematics.

Quantifying external and internal loading requires kinetic instrumentation and model-based inference. Force plates-single, dual, or multi-platform arrays-measure ground reaction forces (GRFs) and center-of-pressure (COP) trajectories basic to inverse-dynamics estimation of joint moments.Instrumented clubs and smart grips quantify grip forces and clubhead dynamics, while launch monitors (radar/optical) supply ball and club-level metrics (ball speed, launch angle, spin) useful for performance correlates. Synchronization across systems (kinematics, force, EMG, launch monitor) is essential to compute temporally aligned kinetics and to attribute mechanical events to neuromuscular activation patterns.

Neuromuscular assessment relies primarily on surface electromyography (sEMG) with selective use of fine-wire electrodes for deep rotator cuff or pelvic musculature where appropriate. Best-practice signal processing includes band-pass filtering (typically 20-450 Hz), notch filtering for mains interference, full-wave rectification, and computation of time-domain metrics such as root-mean-square (RMS) and activation onset latency relative to kinematic events. The table below summarizes common modalities, their primary outputs, and practical sampling guidelines for golf-swing evaluation.

| Modality | Primary Output | Recommended Sampling |

|---|---|---|

| Optical mocap | 3D joint kinematics, segment rotation | 200-500 Hz |

| IMUs / Wearables | Segment orientation, angular velocity | 200-1000 Hz |

| force plates | GRF vectors, COP, joint moments (via inverse dynamics) | 1000 Hz |

| sEMG | muscle activation timing, amplitude | 1000-2000 Hz |

| launch monitor | ball/club kinematics, spin | 1000 Hz (device-dependent) |

To translate raw measures into actionable coaching or clinical recommendations, implement a reproducible pipeline: synchronized acquisition, sensor fusion (e.g.,marker-based + IMU corrections),physiologically plausible filtering,and validated biomechanical models for inverse dynamics. Quality control procedures-inter- and intra-session reliability testing, sensor drift checks, and informed handling of soft-tissue artifacts-are non-negotiable. Recommended practical checklist for both field and lab:

- Define outcome metrics (e.g., peak hip rotation velocity, L5-S1 shear);

- Standardize setup (marker set, electrode placement, club instrumentation);

- synchronize systems using hardware triggers or timestamp alignment;

- Report processing parameters (filters, normalization, event detection algorithms);

- Benchmark against norms or asymmetry thresholds to inform injury risk and technique modification.

Adherence to these practices enhances interpretability, facilitates cross-study comparisons, and supports evidence-based refinements to swing technique while mitigating injury risk.

Coaching and Training Interventions Targeting Strength, Mobility, and Motor Learning

Contemporary practice integrates targeted resistance training, mobility conditioning, and evidence-informed motor learning to optimize the kinetic chain and improve reproducibility of the swing. Empirical kinematic and kinetic data indicate that improvements in proximal stability and distal speed transfer are best achieved when interventions are organized around the swing’s force‑production phases (preload, acceleration, deceleration). Coaches should thus align exercise selection with specific mechanical goals-such as, enhancing rate of torque development at the hips to increase clubhead speed, or restoring thoracic rotation to preserve horizontal separation between pelvis and shoulders. Intervention specificity and measurable outcomes are essential for translating laboratory findings into field gains.

Program content should emphasize discrete, evidence‑based targets. Recommended emphases include:

- Rotational power – med ball rotational throws and band resistive chops to train high‑velocity core torque transfer.

- Hip and glute strength – bilateral and unilateral hip extension to support pelvis stability during transition.

- Thoracic mobility – graded thoracic rotations and neural flossing to restore upper spine dissociation from the lumbar region.

- scapular control – low‑load dynamic stabilisation to maintain clubface orientation through impact.

- Neuromuscular timing – plyometric sequencing and overspeed drills to reinforce proximal‑to‑distal sequencing.

Progression requires planned loading and clear dosage targets. Short, specific mesocycles that convert strength into power and then into skill transfer are recommended. A pragmatic weekly template might follow strength (2 sessions), power/transfer (1-2 sessions) and versatility/motor control (2 sessions) with integrated on‑course repetition. The table below provides a concise example of exercise-to-dose mapping suitable for mid‑amateur golfers:

| Target | Example Exercise | Weekly Frequency |

|---|---|---|

| Rotational Power | Med‑ball rotational throw | 2× |

| Hip Strength | Single‑leg Romanian deadlift | 2× |

| Thoracic Mobility | Segmental rotations | 3× (short) |

Motor learning strategies must be explicit and task‑specific to ensure retention and transfer. Employ an external focus of attention (e.g.,ball flight or target line),variable practice schedules to enhance adaptability,and reduced augmented feedback as competence increases. Constraint‑led approaches-manipulating equipment, stance or task demands-can accelerate self‑organisation of efficient movement patterns. Quantitative biofeedback (inertial sensors, launch monitors) should be used sparingly and framed within performance goals to avoid dependency; qualitative video review combined with augmented feedback epochs yields the most reliable long‑term retention according to current literature.

injury prevention and long‑term athlete development require ongoing screening and collaboration between coaches, strength professionals and healthcare providers. Monitor movement quality (hip internal rotation, thoracic rotation, knee valgus control), training load (session RPE, swing counts) and objective performance markers (clubhead speed, pelvis‑thorax separation). Incorporate progressive neuromuscular control drills and conditional rest when asymmetries or pain emerge.Emphasise dialog, documentation and iterative adjustment-data‑driven coaching is the mechanism by which biomechanical insights become durable improvements in both performance and athlete health.

Equipment Interactions and individualization of Technique Through Club Fitting and Grip Adjustments

The reciprocal relationship between instrument design and human movement profile is central to contemporary biomechanical inquiry.Empirical studies demonstrate that alterations in **shaft flex**, **club length**, or **head inertia** modulate distal kinematics and proximal sequencing, often producing measurable changes in clubhead speed, launch angle, and dispersion. From a mechanistic perspective, small changes to equipment parameters can shift the temporal coordination of the kinematic chain, thereby altering energy transfer and the pattern of segmental contributions required to reproduce a desired shot shape.

Individualization requires quantification: three-dimensional motion capture and force-plate analysis permit objective mapping of a player’s kinetic and kinematic signatures to specific club properties. When a golfer exhibits delayed hip rotation or excessive lateral sway, for example, ergonomic adjustments such as a shorter shaft or altered lie angle can reduce compensatory motions and improve repeatability. Emphasis should be placed on matching **equipment inertia properties** to the player’s neuromuscular capacity so that desired swing tempos and impact conditions are achievable without inducing maladaptive technique changes.

grip dimensionality and pressure distribution are frequently underappreciated determinants of shot outcome. Modifying **grip size** and taper profile influences forearm pronation-supination coupling and wrist hinge mechanics; concomitantly, coached reductions in excessive grip force restore elastic recoil and improve smash factor. Clinicians and coaches should therefore treat grip interventions as both mechanical and sensorimotor: the change alters the mechanical interface while together re-mapping proprioceptive feedback loops that guide fine-tuned motor control during the downswing and at impact.

Practical fitting protocols integrate subjective comfort with objective metrics. A standard session blends static measurements with dynamic trials under instrumentation, yielding actionable adjustments. Typical procedural elements include:

- Baseline screening: anthropometrics, range of motion, and injury history.

- Dynamic assessment: clubhead speed, launch conditions, and impact location using launch monitors.

- Iterative tuning: progressive alterations to shaft,lie,and grip,with immediate feedback loops.

The table below presents concise examples linking common fitting choices to biomechanical rationales.

| Parameter | Common Adjustment | Biomechanical Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Shaft Flex | Stiffer for high-speed players | Reduces unwanted shaft deformation and promotes consistent launch |

| Lie Angle | More upright for taller stance | Aligns clubface at impact to the golfer’s swing plane |

| Grip Size | Slightly larger for strong hand torque | Decreases excessive wrist flexion and release variability |

Q&A

Note on search results

– The web search results provided with the prompt refer to the letter “Q” and are not relevant to the topic of golf-swing biomechanics. Below is an evidence-oriented, academically framed Q&A prepared independently to address the requested topics: kinematics, kinetics, neuromuscular dynamics, technique refinement, and injury risk reduction.

Q1: What is meant by “biomechanical analysis of the golf swing”?

A1: Biomechanical analysis of the golf swing is the systematic study of the movement patterns (kinematics),the forces and moments produced (kinetics),and the underlying neuromuscular control (timing and magnitude of muscle activation) that together produce the golf swing. The objective is to quantify how human tissues, joints, and the club interact to produce performance outcomes (e.g., clubhead speed, ball launch) and to identify movement strategies that maximize efficiency and minimize injury risk.

Q2: How is the golf swing typically segmented for biomechanical study?

A2: The swing is commonly divided into phases to standardize analysis: address/set-up, takeaway, backswing, transition/top of backswing, downswing, impact, and follow-through. Researchers and clinicians may further subdivide phases (e.g.,early vs. late downswing) depending on the variables of interest. Temporal normalization (e.g., percent of swing time) is often used to compare across individuals.

Q3: What primary kinematic variables are used to describe the golf swing?

A3: Key kinematic variables include joint angles and angular velocities (pelvis, thorax, hips, knees, ankles, shoulder, elbow, wrist), segmental orientations (pelvis, thorax, lead and trail arms), clubhead trajectory and velocity, spine inclination, and separation between pelvis and thorax (commonly termed X-factor). Center of mass (CoM) displacement and segmental angular accelerations are also important.

Q4: Which kinetic metrics are most informative in golf-swing analysis?

A4: Essential kinetic metrics include ground reaction forces (GRFs) and their vertical, anterior-posterior, and medial-lateral components; net joint moments and joint reaction forces (derived via inverse dynamics); joint power (especially hips, trunk, and shoulders); and external moments acting on the club (torque about the grip). Rate of force development and impulse measures (e.g.,during weight shift and push-off) are also informative.

Q5: What methods are used to measure kinematics and kinetics?

A5: Laboratory-level methods include optical motion-capture systems (marker-based or markerless), inertial measurement units (imus) for field measurements, high-speed video, force plates (single or multiple) for GRFs, instrumented clubs (strain gauges, accelerometers, gyroscopes), and pressure insoles. Kinetics are commonly computed using inverse dynamics combining motion data, GRFs, and anthropometric models. Surface electromyography (sEMG) is used to assess neuromuscular activation.

Q6: What does “kinematic sequencing” or the “proximal-to-distal sequence” mean in the golf swing?

A6: Kinematic sequencing refers to the timing pattern where larger proximal segments (pelvis) initiate rotation, followed by successive activation and rotation of more distal segments (thorax, shoulders, arms, club) – a proximal-to-distal kinematic chain. Optimal sequencing produces efficient energy transfer and maximizes clubhead speed. Deviations (e.g.,early arm acceleration) can reduce efficiency and increase joint loading.

Q7: How are neuromuscular dynamics assessed and interpreted?

A7: Neuromuscular dynamics are assessed primarily with sEMG,capturing onset timing,duration,and amplitude of muscle activation across muscles relevant to the swing (e.g., gluteus maximus/medius, erector spinae, obliques, pectoralis major, latissimus dorsi, forearm flexors/extensors). Interpretation focuses on coordination patterns (e.g., sequencing of trunk rotators and hip extensors), co-contraction levels (which influence joint stiffness), and timing relative to swing phases (e.g., pre-activation before downswing).

Q8: What biomechanical features correlate most strongly with performance (clubhead speed, ball speed, accuracy)?

A8: Strong correlates include peak angular velocity of the thorax and lead arm, effective X-factor (pelvis-thorax separation and its angular velocity), efficient proximal-to-distal sequencing, optimized ground reaction force generation and transfer (especially lateral-to-medial and vertical components), and minimal loss of clubhead speed pre-impact due to early release.Coordination that maximizes proximal contribution (hips and trunk) while controlling distal timing supports both speed and accuracy.

Q9: Which swing mechanics are most associated with injury, particularly low back pain?

A9: Risk factors for musculoskeletal injury include excessive or repeated high torsional loads on the lumbar spine (large X-factor combined with high trunk axial rotation velocities), abrupt or poorly timed weight shifts, excessive lateral bending or extension at impact, high peak compression/shear forces at lumbar segments, and inadequate hip mobility prompting compensatory lumbar motion. Repetitive overuse of wrist and elbow extensors/flexors (e.g., in golfers with poor technique) also contributes to tendinopathy.

Q10: How can analysis guide technique refinement to reduce injury risk while maintaining performance?

A10: analysis identifies inefficient or risky movement patterns (e.g., excessive lumbar rotation, early arm-dominant downswing). Interventions can include: modifying swing mechanics to reduce lumbar shear (e.g., reducing extreme X-factor by increasing hip contribution), improving sequencing via drills that promote hip-to-trunk rotation timing, strengthening and motor control training for stabilizers (deep trunk muscles, hip abductors/gluteals), mobility work for hips and thoracic spine, and optimizing ground-force application patterns. Changes should be individualized and progressed cautiously to avoid performance loss or new injury.Q11: What role do equipment and club fitting play biomechanically?

A11: club length, shaft flex/stiffness, lie angle, grip size, and clubhead mass distribution alter kinematics (swing plane, wrist angles, release timing) and kinetics (inertial demands, joint moments). Properly fitted clubs can reduce compensatory movements, improve energy transfer, and reduce undue loading on joints. Biomechanical testing can inform fitting by measuring how equipment changes segmental dynamics and clubhead outcomes.

Q12: What are common measurement pitfalls and limitations in applied biomechanics for golf?

A12: Pitfalls include: over-reliance on single-trial data (high variability within players), marker occlusion and skin motion artifact with optical systems, limited ecological validity of lab settings (e.g., indoor tees vs. on-course variability), inadequate sampling rates for high-speed events (impact), and improper normalization of EMG/kinetic data. Additionally, causal inference from cross-sectional correlations is limited; longitudinal and interventional designs are needed to establish cause-effect.Q13: How should clinicians or coaches implement biomechanical findings in practice?

A13: Use biomechanical data to prioritize individualized interventions: assess mobility, strength, and motor control deficits; use simple field-kind measures (IMUs, video) to monitor key parameters (pelvis-thorax separation, timing of weight shift, swing plane); design progressive drills and conditioning targeting identified deficits; and re-evaluate with objective metrics to confirm desired kinematic and kinetic changes while monitoring symptoms and performance metrics.

Q14: What training interventions have biomechanical rationale to improve performance safely?

A14: Interventions include: (1) neuromuscular training to optimize sequencing (drills that promote hip lead and delayed arm release); (2) strength and power training for hips, trunk rotators, and posterior chain to increase force production and rate of force development; (3) mobility and thoracic rotation exercises to allow safer trunk rotation; (4) proprioceptive and balance training to improve force application through the ground; (5) eccentric control training for deceleration to reduce joint loading. Integrate specificity to transfer gains to the swing.

Q15: Which populations require special biomechanical consideration?

A15: Junior golfers (growth-related changes in coordination and strength), older golfers (reduced mobility and muscle power), golfers with prior injuries (spine, shoulder, elbow), and elite vs. recreational players (different demands and tolerance). Age-, sex-, and ability-specific normative data and tailored interventions are important.Q16: What are recommended objective metrics to track over time?

A16: Suggested longitudinal metrics: clubhead speed; ball launch parameters (ball speed, spin, launch angle); pelvis and thorax peak angular velocities and timing; X-factor and X-factor stretch; peak GRFs and their timing; peak joint moments/powers (hips, lumbar, shoulder); EMG timing for key muscles (relative onset and peak); and CoM displacement. Track symptom status and functional tests (e.g., single-leg balance, rotational power tests).

Q17: How can field-based technologies be used reliably?

A17: IMUs (validated against optical systems), high-speed video with calibrated markers or consistent camera placement, instrumented clubs, and pressure insoles provide practical measures.To improve reliability: use standardized protocols, multiple trials and averaging, consistent warm-up and ball/tee conditions, and periodic calibration checks. Be cautious interpreting absolute values across devices.

Q18: What are the principal methodological approaches for computing kinetics during the swing?

A18: The principal approach is inverse dynamics: combine 3D kinematics, GRFs, and anthropometric data to compute net joint moments and powers. Multi-segmental models of the upper extremity and trunk with appropriate inertial parameters are necessary. For more detailed tissue-level estimates, musculoskeletal modeling with optimization or EMG-informed force estimation can be used, acknowledging model assumptions and sensitivity to inputs.

Q19: what are current research gaps and future directions?

A19: Gaps include: longitudinal studies linking biomechanical variables to injury incidence; improved understanding of inter-individual variability and optimal movement phenotypes; integration of muscle-tendon and neuromotor models to predict tissue loading; field-validated wearable models that reliably estimate joint loads; and randomized trials testing biomechanically informed interventions. Also needed are normative databases across ages, sexes, and skill levels.

Q20: Practical summary of evidence-based coaching and clinical recommendations

A20: – Assess movement with objective measures where possible; prioritize multiple trials and standardized conditions.

– Emphasize proximal power generation (hips/trunk) and optimal sequencing rather than forcing maximal trunk rotation.

– Address mobility deficits (thoracic spine, hips) to reduce compensatory lumbar stress.

– Train strength and rate of force development in hip extensors/rotators and posterior chain, and improve neuromuscular timing with sport-specific drills.- Monitor and optimize ground reaction force application and timing.

– Fit equipment to the player’s anthropometrics and capabilities.

– Progress technique changes gradually, monitor performance and symptoms, and individualize interventions.

– For high-risk players (history of low back pain), reduce extreme X-factor strategies and emphasize controlled rotation with adequate hip contribution.

Q21: How should researchers and clinicians report biomechanical studies to be clinically useful?

A21: Report participant demographics (age, sex, handicap/skill), measurement systems and sampling rates, marker/set-up conventions, definitions of phases and outcome variables, normalization procedures, trial count and averaging, and reliability metrics. Provide practical interpretation for coaches/clinicians (e.g., effect sizes, expected change ranges) and include limitations and applicability.

If you would like, I can:

– Draft a concise assessment protocol (field or lab) with specific variables to measure.

– Create a short set of drills and conditioning exercises linked to specific biomechanical deficits (e.g., improving X-factor control, increasing hip contribution).

– Produce a sample data-report template for clinicians that translates lab metrics into coaching cues and rehab goals.

Key Takeaways

a biomechanical analysis of the golf swing integrates kinematic descriptions,kinetic cause-effect relationships,and neuromuscular control strategies to reveal how coordinated motion,force production,and timing produce performance outcomes and influence injury risk. The evidence reviewed underscores that optimal clubhead speed and shot consistency arise from intersegmental sequencing, appropriate ground-reaction force utilization, and efficient energy transfer through the kinetic chain; conversely, deviations in sequencing, excessive localized loading, or compromised neuromuscular control increase the likelihood of overuse and acute injuries.

For practitioners, these findings translate into concrete, evidence-informed interventions: coaching that emphasizes proximal-to-distal sequencing and ground-force mechanics, conditioning programs targeting rotational strength and eccentric control of the trunk and lower limb, and individualized swing adaptations when anatomical or pathological constraints are present. Objective assessment-using motion capture, force platforms, and validated electromyographic or wearable sensors-should guide technique modification and load management, particularly for athletes with a history of lumbar, shoulder, or elbow pathology.

Limitations of the current literature include heterogeneous study designs, limited longitudinal and in-field investigations, and variable participant skill levels; thus, future research should prioritize prospective cohort studies, standardized biomechanical metrics, and translational trials that evaluate how targeted interventions alter both performance and musculoskeletal health. Integrating computational modeling and machine-learning approaches may further elucidate complex multisegmental interactions and enable personalized optimization of swing mechanics.

Ultimately, bridging rigorous biomechanical insight with applied coaching and rehabilitation offers the most promising pathway to enhance performance while mitigating injury risk. Continued interdisciplinary collaboration between biomechanists, clinicians, strength and conditioning specialists, and coaches will be essential to translate empirical findings into safer, more effective golf practice and training.

Biomechanical Analysis of the Golf Swing

Why biomechanics matter in the golf swing

Understanding the biomechanics of the golf swing turns a complex athletic movement into a repeatable, trainable process. biomechanical analysis blends kinematics (motion) and kinetics (forces) to explain why a swing produces certain ball flight, clubhead speed, and impact quality.By measuring movement patterns and forces, players and coaches can reduce variability, increase distance, and minimize injury risk.

Key kinematic and kinetic components

Grip, wrist action, and clubface control

- Grip pressure: moderate and consistent pressure prevents early wrist break and face rotation at impact.

- Wrist hinge: controlled wrist set in the backswing stores potential energy for release in the downswing.

- Clubface orientation: small degrees of face angle at impact have large effects on launch direction and spin.

Setup,posture,and athletic stance

Optimal posture provides a stable central axis for rotation. Key posture elements include:

- Neutral spine with slight anterior pelvic tilt

- Knee flex and athletic balance over midfoot

- Shoulder tilt matching intended attack angle (slight slope for irons)

sequencing and the kinematic chain

The kinematic sequence is the order and timing of segment rotations: hips → torso → upper torso/shoulders → arms → club. Efficient sequencing maximizes energy transfer to the clubhead with minimal stress to joints.

Ground reaction forces (GRF) and weight shift

Ground reaction and weight transfer create torque and stabilize the swing. Efficient swings use:

- Initial weight on inside of trail foot during setup

- Pressure transfer to lead foot during downswing to create lateral force and vertical loading

- Use of GRF to increase clubhead speed without excessive muscular effort

Hip and torso rotation

Hip turn and separation (torso vs hips) produce the stretch-shortening cycle in the trunk muscles. Maximum hip rotation followed by delayed torso rotation (X-factor) increases clubhead speed and stretch stress in thoracolumbar fascia-useful for power but must be managed to prevent low-back overload.

Impact mechanics and follow-through

- Square clubface and neutral shaft lean at impact maximize smash factor and accuracy.

- A forward shaft lean for irons reduces spin and improves compression.

- Follow-through reflects energy dissipation-good balance and extension indicate efficient transfer.

Performance metrics to measure (and ideal target ranges)

Below is a practical table with common metrics used in biomechanical and performance analysis. These values vary by player level, sex, age and equipment; use them as benchmarks.

| Metric | Why it matters | Benchmark (male amateur) |

|---|---|---|

| Driver clubhead speed | Primary determinant of distance | 85-110 mph |

| Smash factor | Energy transfer to ball | 1.45-1.50 |

| Launch angle (driver) | Optimizes carry + roll | 10-14° |

| Spin rate (driver) | Controls carry and roll | 1800-3000 rpm |

| Pelvic rotation | Generates torque | 35-50° |

Tools & technology for biomechanical analysis

Modern analysis uses a combination of hardware and software:

- High-speed video (240-1000+ fps) for swing path and face angle

- Motion capture systems (optical marker-based) for full-body kinematics

- Inertial Measurement Units (IMUs) for on-course, markerless data

- Force plates and pressure mats to measure ground reaction forces and weight shift

- Launch monitors (TrackMan, GCQuad, Flightscope) to measure ball speed, launch angle, and spin

Common swing faults: biomechanical causes and fixes

Below are frequent performance problems with biomechanical explanations and practical corrections.

- Over-the-top downswing

- Cause: early upper-body rotation and incorrect sequencing

- Fix: drill to feel inside path (pump drill) and maintain pelvic lead in transition

- Early extension (standing up through impact)

- Cause: lack of hip mobility or weak glutes; torso moves forward instead of rotating

- Fix: hinge/hip mobility drills, impact bag to practice staying behind the ball

- Slice (open face at impact)

- Cause: weak forearm rotation, exit path outside-in

- Fix: strengthening pronation/supination, face closing drills, path correction with alignment rods

- Cause: poor sequencing, low clubhead speed, shallow angle of attack

- Fix: speed training, tempo work, and load/unload drills to increase separation

Practical drills and training tips (biomechanics-driven)

Use these drills to improve kinematic sequencing, ground force usage, and impact consistency:

- X-Factor Stretch Drill: On the range, pause at top of backswing and feel hip turn vs shoulder turn separately to enhance separation.

- Step-Through Drill (weight shift): Start with feet together, take a short backswing and step into the lead foot during the downswing to exaggerate GRF transfer and feel forward pressure.

- Impact Bag: Hit into an impact bag to groove forward shaft lean and compress the ball with irons.

- Slow-Motion Kinematic Repeats: use 50-60% speed swings focusing on sequencing: hips, torso, arms, club-record with slow-mo video for review.

- Resistance Band Rotations: Build rotational power with elastic band exercises that mimic swing pattern.

Programming practice sessions from biomechanical data

Turn measured data into a weekly plan:

- Day 1 – Speed & power: weighted club swings, medicine ball rotational throws, Plyo hops for GRF.

- day 2 – Technique & sequencing: motion-capture or slow-motion video feedback; 30-40 purposeful swings with drills.

- Day 3 – On-course simulation: apply launch monitor settings and pressure mat feedback to practice shot shaping.

- Weekly review: compare launch monitor and motion metrics to measure progress in clubhead speed, smash factor, and path consistency.

Injury prevention: mechanics that protect the body

Good biomechanics reduces cumulative stress. Focus on:

- Hip mobility and glute strength to protect the lumbar spine

- Balanced shoulder work to avoid over-rotation stress

- Proper sequencing to prevent overuse of the wrists and elbows

- Gradual ramp-up of speed training to avoid acute tendon overload

Case study: Translating biomechanical insight into 20 yards of driver distance

Player profile: 38-year-old male amateur with inconsistent launch and moderate spin.

- initial metrics: 92 mph clubhead speed, 1.42 smash factor, 3200 rpm spin, 9° launch, 230 yd carry.

- Biomech findings: limited pelvic rotation (28°), early arm-dominant release, weak weight shift (force plate showed 55% weight remained on trail foot at impact).

- Intervention (8 weeks): hip mobility program, X-factor drills, step-through weight-shift drill, launch monitor drills to increase smash factor.

- Outcome: 97 mph clubhead speed,1.48 smash factor, 12° launch, 2400 rpm spin, 250 yd carry – ~20 yd increase due to improved sequencing and better energy transfer.

First-hand coaching tips (practical coach/player exchange)

As a coach, focus feedback on one measurable change at a time:

- Start with a single metric (e.g., launch angle or clubhead speed).

- Use video or launch monitor data to show the player immediate cause-effect.

- Prescribe two drills and one strength/mobility exercise per week to avoid overwhelming the player.

SEO & content tips for coaches and golf content creators

When publishing biomechanical content,use targeted long-tail keywords naturally to improve search visibility:

- Examples: “golf swing biomechanics”,”increase clubhead speed drills”,”ground reaction force golf swing”,”how to improve X-factor in golf”

- Include data-backed images,annotated slow-motion clips,and tables of benchmark metrics to increase dwell time.

- Use structured headings (H1, H2, H3), alt text for images with keywords, and meta description that includes primary search terms.

Fast reference checklist for a biomechanical swing analysis session

- Collect baseline numbers: clubhead speed, ball speed, launch angle, spin, path, face angle

- Record full-body motion capture or high-speed video

- Measure GRF with force plate/pressure mat

- Identify 2-3 key faults and prioritize interventions

- set measurable goals and review every 4-8 weeks

By combining objective measurement (launch monitors, motion capture, force plates) with targeted drills and strength work, golfers can turn biomechanical insight into repeatable gains: more distance, tighter dispersion, and a healthier swing for long-term performance.