Note: the supplied web search results relate to AC Milan and are not relevant to the requested topic. Below is an original academic-style introduction for the article “Biomechanical Analysis of the Golf Swing for Performance.”

Introduction

Optimizing the golf swing remains a central objective in both sports science and applied coaching because small mechanical adjustments can produce disproportionate effects on accuracy, distance, and injury risk. Biomechanical analysis-integrating kinematic and kinetic measurements with musculoskeletal modeling-provides a rigorous framework to quantify the movement patterns, force generation, and segmental coordination that underlie effective shots. By translating complex motion data into interpretable performance metrics,biomechanics enables evidence-based refinement of technique and individualized training prescriptions.

This article synthesizes current biomechanical methods and empirical findings to identify the key determinants of swing performance.We review conventions for data capture (motion capture, inertial sensors, force platforms, and electromyography), describe analytic approaches for assessing sequencing, timing, and energy transfer (including inverse dynamics and segmental power analysis), and consider context-specific modifiers such as club type, shot intent, and player anthropometrics.Special attention is given to temporal-spatial coordination-frequently enough characterized as proximal-to-distal sequencing-and the relationships among trunk rotation, pelvic motion, wrist mechanics, and ground-reaction forces that collectively influence clubhead speed and impact conditions.

Beyond descriptive analysis,this paper evaluates how biomechanical insights inform targeted interventions: technical cues,strength and conditioning programs,and equipment fitting. We also address methodological limitations, including variability across skill levels, challenges in ecological validity, and constraints of current modeling assumptions. The article concludes with recommendations for integrating biomechanical diagnostics into practice and outlines avenues for future research to further close the gap between laboratory measurement and on-course performance.

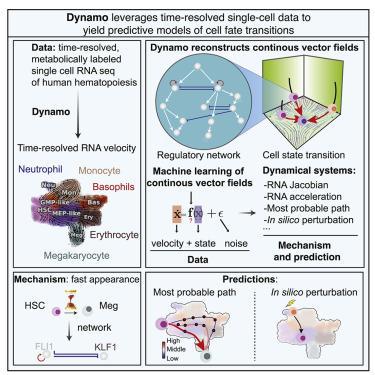

Kinematic Sequencing and Temporal Coordination of Lower and Upper Body for Optimal energy Transfer

The production of maximal clubhead speed depends on an efficient proximal-to-distal kinematic chain in which the lower-body segments initiate motion and the upper-body segments sequentially amplify angular velocity. In well-coordinated swings the pelvis begins the downswing with an abrupt rotational acceleration that is rapidly followed by thoracic rotation, upper-extremity acceleration and, high angular velocity at the wrists and clubhead. this ordered progression minimizes dissipative relative motion between segments, thereby reducing internal work and maximizing the transfer of mechanical energy from the ground through the body to the club.

Biomechanically, optimal transfer requires precise temporal coordination of joint torques, stretch-shortening cycle utilization and intersegmental force transfer. Ground reaction forces provide the initial impulse while hip extensors and rotators generate torque that is transmitted through a stiffened core to the shoulder girdle.The coordinated timing of eccentric preloading and concentric release across muscle groups-particularly gluteals, erector spinae, obliques and rotator cuff-facilitates elastic recoil and increases net angular impulse delivered to distal segments. Emphasis on rhythm and controlled deceleration of proximal segments is central to conserving energy for distal acceleration.

Common temporal faults disrupt this sequencing and reduce efficiency. Examples include premature arm acceleration (often described as “casting”), early pelvic stoppage with exaggerated upper-body rotation, and a reversed sequence in which the upper body leads the lower body. Each fault creates segmental dissociation that: increases joint loading, reduces clubhead speed, and may elevate injury risk to the lumbar spine and shoulder complex.

- pelvic-first drills: step-and-rotate and resistance-band lead-leg drives to reinforce early hip drive.

- Sequencing tempo work: metronome-guided swings that exaggerate a pause at transition to restore correct timing.

- Reactive training: medicine-ball throws and plyometrics to enhance stretch-shortening coordination across segments.

- Feedback tools: wearable IMUs, video with frame-by-frame review, and force-plate data to quantify peak timing and order.

Coachable timing benchmarks

| Segment | Typical peak order | Coaching cue |

|---|---|---|

| Pelvis | 1 (initiate downswing) | “drive the belt buckle to the target” |

| Thorax | 2 (transfer rotation) | “Turn chest through impact” |

| Arms/club | 3 (final acceleration) | “Keep lag, release late” |

Translating kinematic principles into a training curriculum requires progressive overload, objective measurement and individualized constraints-led coaching. Begin with low‑speed, high‑repetition patterning that prioritizes pelvic initiation and trunk stiffness, then incrementally introduce speed and resistance while monitoring temporal markers. Use objective metrics (e.g., IMU-derived time-to-peak angular velocity, GRF impulse) to set measurable targets. Ultimately,integrating strength,mobility and motor-control drills with targeted feedback produces reproducible improvements in energy transfer and on-course performance.

Kinetic Analysis of Ground Reaction Forces and Weight Transfer with Practical Training Recommendations

Ground reaction forces (GRFs) constitute the mechanical interface through which lower‑limb musculature imparts momentum to the golf club; they are therefore basic to understanding swing kinetics and performance. three orthogonal GRF components-**vertical**, **anterior-posterior**, and **medio‑lateral**-combine to produce resultant force vectors and moments at the foot-ground contact that drive center‑of‑mass (CoM) acceleration and clubhead velocity. Analysis of the force‑time curve and computed impulse during the downswing provides insight into both the magnitude and timing of force generation: a rapid rise in vertical and anterior components promptly prior to impact is characteristic of effective power transfer, whereas prolonged or misdirected lateral forces indicate inefficiencies or compensatory patterns.

Efficient weight transfer in the swing is a coordinated sequence of loading and unloading between the trail and lead limbs. During the backswing and transition, skilled golfers typically show a brief **trail‑leg load** (increased vertical GRF) followed by rapid transfer and force redirection to the lead leg through the downswing-this produces the necessary ground reaction impulse to accelerate the pelvis and upper torso.Faulty patterns such as early lateral slide, insufficient trail‑leg loading, or premature extension alter the timing of peak GRF and reduce R‑X (resultant) alignment, leading to decreased clubhead speed and inconsistent ball contact. Evaluating rate of force development (RFD) and center‑of‑pressure (CoP) progression yields actionable diagnostic markers for these faults.

Instrumented assessment enhances objective prescription: lab and field systems-including force plates,pressure mats,and instrumented insoles synchronized with kinematics-quantify GRF magnitudes,CoP paths,and temporal events (e.g., peak vertical GRF time relative to impact). The table below summarizes typical kinetic signatures across three critical swing phases with compact coaching cues for targeted interventions.

| Phase | GRF Pattern | Coaching Cue |

|---|---|---|

| Early backswing | Increased trail vertical load | “Load the trail leg” – feel rear pressure |

| Transition/Downswing | Rapid shift anteriorly and laterally to lead | “Explode to the lead” – accelerate ground push |

| Impact | Peak vertical and forward GRF; CoP near lead forefoot | “Drive through the ball” – stabilize lead foot |

Practical training should progress from isolated force‑production to integrated swing application. Recommended drills include:

- Split‑stance force plate drill – perform slow backswing/fast downswing while monitoring CoP shift; 3 sets × 8 reps.

- Step‑through downswing – step lead foot toward target during transition to train rapid weight transfer; 4 sets × 6 reps.

- Med‑ball lateral throws – emphasize pelvic rotation with ground push; 3 sets × 10 reps.

- Banded resisted rotations – reinforce force transfer from hips to torso while maintaining lead‑foot contact; 3 sets × 12 reps.

Each exercise should be performed with attentional focus on foot pressure and CoP movement rather than solely on upper‑body mechanics.

Integration into a periodized program requires objective monitoring and conservative progression. Use asymmetry indices (target <10-15% inter‑limb difference) and temporal markers (peak vertical GRF occurring ~20-50 ms prior to impact in skilled swings) to evaluate improvement; expect measurable changes within a 6-8 week block of dedicated force‑transfer training. Emphasize neuromuscular control and progressive loading to minimize injury risk-begin with low‑velocity technical repetitions, progress to accelerated med‑ball work, and finally reintroduce full‑speed swings with biomechanical feedback. Consistent re‑assessment with force or pressure systems ensures that technical gains translate into improved kinetic efficiency and on‑course performance.

Trunk and Pelvic Mechanics: Rotation,Flexion and Stability Strategies to Maximize Clubhead Velocity

Efficient force production in the golf swing is predicated on coordinated transverse-plane rotation between the pelvis and thorax. Empirical analyses indicate that optimal angular separation-commonly referred to as the X‑factor-allows for substantial elastic energy storage in the lumbopelvic region. In practice, a controlled **pelvic‑first sequencing** followed by rapid thoracic rotation creates a proximal‑to‑distal transfer of angular momentum that amplifies distal clubhead velocity while minimizing deleterious shear forces at the lumbar spine.

Spinal flexion and extension dynamics modulate the orientation of the rib cage relative to the pelvis and influence the effective lever arm for rotational torque. Maintaining neutral lumbar lordosis during the backswing and a slight extension through impact preserves vertebral alignment and optimizes fascial tension in the obliques and erector spinae. Excessive lateral flexion or early extension compromises rotational axis stability and shifts loads into passive spinal structures, increasing injury risk and reducing the efficiency of torque transmission.

Core stability strategies should prioritize dynamic stiffness that permits rotation while resisting unwanted translation. effective on‑course and training cues include:

- Anti‑rotation drills to improve transverse plane control;

- Hip hinge and glute‑activation exercises to generate pelvic torque;

- Controlled X‑factor exaggeration drills to teach safe separation;

- tempo and acceleration drills to refine sequencing and timing.

These interventions create a stable proximal platform from which maximal distal acceleration can be produced without excessive compensatory motions.

Quantitative markers of efficient trunk-pelvis interplay can be summarized simply for coaching application. The table below presents representative target ranges observed in performance cohorts and their mechanical implications.

| Metric | Representative Range | Performance Implication |

|---|---|---|

| Pelvic rotation (backswing) | 40°-50° | Foundation for torque generation |

| Thoracic rotation (backswing) | 80°-100° | Creates X‑factor magnitude |

| X‑factor separation | 30°-50° | Correlates with clubhead speed |

| Pelvic‑to‑thorax timing | Pelvis leads by 0.05-0.15 s | Optimizes momentum transfer |

From an injury‑prevention and coaching viewpoint, emphasize progressive loading, objective assessment, and individualized modification of rotational demands. Use wearable IMUs or 3D motion capture to monitor kinematic patterns and ensure that increases in rotational amplitude are accompanied by appropriate neuromuscular control. The practical takeaway: prioritize **proximal stability with adaptive mobility**, measure sequencing rather than simply amplifying rotation, and progress training to balance maximal clubhead velocity with long‑term spinal health.

Shoulder, Elbow and Wrist Dynamics: Joint Loading, timing and Injury Prevention Protocols

The shoulder, elbow and wrist operate as an integrated kinetic chain in the golf swing, with the shoulder complex (scapulothoracic and glenohumeral joints) serving as the proximal driver for distal segmental motion.effective force transfer requires coordinated scapular upward rotation and posterior tilt to maintain glenohumeral centration, while excessive humeral anterior translation or scapular dyskinesis increases shear and compressive loading. At the elbow, repetitive valgus stress on the medial structures and varus/compressive loads laterally are modulated by forearm musculature and joint alignment. The wrist must absorb high impulse forces at ball contact and rapidly transition from cocked to release positions without exceeding physiologic ranges; failure to decelerate the club appropriately shifts loads proximally and elevates injury risk.

Temporal sequencing is critical: a proximal-to-distal activation pattern minimizes peak joint loads while maximizing club head velocity. Optimal sequencing typically demonstrates early pelvis and thorax rotation, followed by shoulder rotation, peak shoulder external rotation at the top of the swing, and then rapid internal rotation of the lead shoulder with concomitant elbow extension and wrist release. Key timing factors include:

- Onset of pelvis rotation relative to hip stability – drives safe torque distribution.

- Peak shoulder angular velocity timing – a delay or premature peak alters elbow/wrist loading.

- Deceleration phase coordination – eccentric control of rotator cuff and forearm muscles reduces impulse peaks.

A concise table highlights common load types, primary joints at risk and concise preventive strategies:

| Load Type | Primary Joint | Injury Mechanism | Preventive Strategy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Valgus shear | Elbow (medial) | Repetitive late-swing torque | Forearm pronator/supinator strengthening |

| Compressive/torsional | Shoulder (GH) | Excessive internal rotation at high speed | Rotator cuff eccentric control |

| High impulse | Wrist | Rapid cocking/uncocking with poor control | Wrist extensor eccentrics; progressive loading |

Injury prevention protocols should be evidence-informed, progressive and sport-specific. Core elements include mobility work for thoracic rotation and scapular mechanics,strength and hypertrophy for rotator cuff and scapular stabilizers,and neuromuscular training for timing and sequencing. Prescriptive examples: eccentric rotator cuff sets (3×10 at controlled tempo), scapular retraction holds with external rotation bias, forearm supination/pronation with incremental resistance, and wrist extensor eccentric loading with slow deceleration drills. Load management principles-session frequency, swing volume, and progressive intensity-must be individualized to the golfer’s training age and competitive demands.

Implementation requires objective screening and ongoing monitoring using validated tools: clinical ROM and strength ratios,motion-capture or inertial sensor assessment of sequencing and angular velocities,and patient-reported pain/function scales. return-to-swing criteria should combine symptom resolution, restoration of pain-free functional ROM, normative strength thresholds (e.g., rotator cuff external/internal strength ratio), and reproducible kinematic sequencing under submaximal loads. Integrating biomechanical feedback with targeted rehabilitation reduces cumulative joint loading, preserves performance metrics and supports long-term participation in high-level golf.

Swing Plane, Clubface Control and Ball Flight Relationships with Drills to Correct Common Faults

Precise coordination of the swing plane with segmental kinematics determines the initial conditions that govern ball flight. The plane described by the club shaft is a macroscopic expression of coordinated rotations across the hips, thorax and shoulders; deviations in axial rotation timing produce alterations in plane inclination and dynamic width. From a biomechanical perspective, a steeper plane increases vertical attack angle and spin rates for short-to-mid irons, whereas a flatter plane promotes shallower attack angles typical of long clubs. Monitoring torso-pelvis separation (X-factor) and the spatial trajectory of the lead arm provides objective markers for identifying plane consistency across repetitions. In practice, high-speed video and inertial sensors quantify plane tilt and allow targeted motor learning interventions to stabilize this kinematic variable.

Clubface orientation at impact is the proximal determinant of initial ball direction and, together with swing path, defines curvature and sidespin. The relationship can be expressed simply: when clubface angle relative to the target line equals swing path, the ball launches straight; when the face is open or closed relative to the path, the ball curves. Thus, control of the clubface requires fine motor regulation of forearm supination/pronation, wrist flexion/extension, and grip pressure during the downswing and through impact.Empirical work shows that small angular deviations (±2-4°) in face angle generate measurable lateral dispersion at typical carry distances; consequently, training should prioritize reproducible forearm torque and consistent release timing rather than purely larger gross-body changes.

characteristic faults emerge from identifiable biomechanical causes. An “over-the-top” steep swing path commonly arises from early lateral weight shift or insufficient hip rotation,producing a leftward pull or slice correction through compensatory face manipulation. Conversely, an excessive inside-out path is often linked to early hip clearance or an overactive upper-body rotation, resulting in pronounced hooks when the face remains closed relative to path. Open clubfaces at impact frequently reflect inadequate wrist closure or a grip that permits excessive radial deviation of the lead wrist; closed faces frequently enough follow from hyperactive forearm supination or excessive hand action. Diagnosing the primary fault requires observing both the path and the face angle at impact to distinguish primary kinematic drivers from secondary compensations.

Practical corrective drills emphasize sensory feedback and constrained repetition to reprogram motor patterns.Recommended exercises include:

- Plane board drill – place a rigid rod along the desired shaft plane during the takeaway to ingrain correct shoulder-turn-to-arm geometry.

- Gate drill for face control – set two tees slightly wider than the clubhead at impact to train square face passage and minimize face rotation errors.

- Towel‑under‑arm – retain connection between torso and lead arm to prevent early separation and inside-out path creation.

- Impact‑bag repetitions – short,focused strikes against a bag to develop stable wrist angles and consistent release timing under load.

- Mirror and slow‑motion playback – combine visual feedback with reduced-speed swings to refine timing of pelvis-thorax separation and face closure sequence.

Structured practice should integrate objective metrics and progressive complexity: begin with isolated drill blocks (low variability, high feedback), progress to variable practice (multiple targets, altered lies) and conclude with pressure simulations. The table below summarizes common faults,their primary biomechanical causes and recommended corrective drills for rapid clinical translation.

| Fault | Primary Biomechanical Cause | Corrective Drill |

|---|---|---|

| Over‑the‑top slice | Early lateral sway / delayed hip rotation | Plane board + hip‑rotation tempo |

| hook (inside‑out) | Excessive early hip clearance | Towel‑under‑arm + slow mirror swings |

| Open face / push | Inadequate wrist closure / weak release | Gate drill + impact‑bag |

muscle Activation Patterns and Neuromuscular Conditioning Programs for Power and Consistency

The golf swing exhibits a classic proximal‑to‑distal activation sequence: pelvic rotation initiates, followed by trunk and shoulder torque, and finally rapid distal release through the arms and wrists. Surface EMG studies consistently demonstrate early, high‑magnitude activation of the gluteus maximus and hamstrings during transition, sustained activation of the external obliques and erector spinae through acceleration, and phasic peaks in the latissimus dorsi and forearm flexors at impact. Temporal precision-milliseconds of difference in onset and peak activity-differentiates high‑velocity, repeatable swings from inconsistent ones; thus, neuromuscular timing is as critical as raw muscle strength for performance outcomes.

Consistency emerges from stable motor programs and adaptive synergies rather than maximal isolated force. Functional co‑contraction around the lumbar spine and shoulder girdle provides the stiffness necessary to transfer ground reaction forces into clubhead speed while eccentric control of the lead arm and wrist governs deceleration and accuracy. Training should therefore target both feedforward anticipatory activation (to set segmental stiffness) and feedback‑driven adjustments (to correct perturbations), with objective monitoring of variability across repetitions to quantify progress.

Conditioning programs that translate to power and reproducibility emphasize multiplanar power, single‑leg stability, and rate‑of‑force development. Core elements include:

- Rotational power: medicine‑ball throws (standing, step‑through, and rotating variations)

- Hip and posterior chain strength: single‑leg RDLs, hip thrusts, band‑resisted lateral walks

- Rate and stretch‑shortening: plyometric lateral bounds, kettlebell swings

- Stability and anti‑rotation: Pallof presses and single‑leg balance with perturbation

- Deceleration control: eccentric wrist/forearm work and slow‑negative cable chops

Programming should manipulate load, velocity, and complexity (e.g., overspeed training, unilateral constraints, and variability) to shift neuromuscular recruitment toward rapid, task‑specific patterns.

optimizing neuromuscular function also requires attention to physiological constraints and risk mitigation. Acute and exercise‑associated muscle cramps can disrupt activation sequencing; they are often related to fatigue, electrolyte/climate stress, or overuse and are managed with targeted hydration and progressive load management. Clinicians should be aware that centrally acting muscle relaxants may impair coordination and reaction time, and persistent weakness or unusual neuromuscular signs warrant medical evaluation for underlying neuromuscular conditions. Integrating recovery, sleep, and graded return‑to‑load protocols reduces maladaptive recruitment and preserves high‑quality motor output.

Objective assessment and progressive periodization anchor transfer from the gym to the course. Use field tests and lab measures-EMG timing windows, force‑plate ground reaction profiles, and clubhead velocity-to set thresholds and guide progression. A concise sample microcycle is provided below for practical application:

| drill | Sets × Reps | Primary Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Med‑ball rotational throws | 4 × 6 (max velocity) | rotational power & timing |

| Single‑leg RDL + cable chop | 3 × 8 each side | Hip/hamstring strength & anti‑rotation |

| Pallof press (slow → explosive) | 3 × 10 | Core stiffness control |

| Eccentric wrist curls | 3 × 12 (3s negative) | Deceleration & impact control |

Regular reassessment of timing, variability, and symptomatology should inform adjustments; aim to progress velocity before load where sport specificity demands rapid force production for both power and consistent ball flight.

Temporal and Spatial Variability Analysis: Assessing Consistency and Implementing Feedback Methods

Quantifying both temporal and spatial aspects of the swing reveals distinct signatures of motor control and adaptability. Temporal metrics-such as **backswing duration**, **transition timing**, and **impact window length**-characterize rhythm and phase relationships across segments, whereas spatial metrics-including **clubhead path**, **swing plane deviation**, and **pelvic rotation amplitude**-describe geometric consistency. Evaluating these domains in concert permits discrimination between stable, skilled patterns and compensatory strategies that may degrade performance or elevate injury risk.

Robust assessment requires instrumentation and analysis pipelines that preserve high-fidelity temporal and spatial data. Commonly used modalities include optical motion capture,inertial measurement units (IMUs),and high-speed videography; each system mandates attention to sampling frequency,sensor alignment,and inter-device synchronization to minimize measurement noise.Statistical descriptors such as standard deviation, coefficient of variation (CV), and root-mean-square error (RMSE) provide concise indices of consistency both within-session (trial-to-trial) and across sessions (retention), enabling longitudinal monitoring of motor learning or fatigue effects.

Analytical techniques that respect the continuous, cyclic nature of the swing are essential. Temporal normalization and time-series alignment (e.g., dynamic time warping or phase registration) permit segmental comparisons self-reliant of absolute duration. Phase-based metrics-such as continuous relative phase between torso and pelvis-and spatial dispersion measures-such as mean absolute deviation of clubhead path-offer complementary perspectives. Key metrics frequently reported in applied research and coaching include:

- Timing CV (backswing-to-downswing ratio)

- Peak angular velocity variability (shoulder and hip)

- Clubhead path SD (degrees from target plane)

- Inter-segment phase lag (degrees)

Translating analysis into effective feedback requires selection of modality and schedule informed by motor learning principles. Augmented feedback can be delivered as **real-time auditory cues** (tempo metronomes),**visual overlays** (trajectory heatmaps),or **haptic prompts** (vibration at critical phases).Evidence supports the use of faded feedback schedules and bandwidth feedback-providing data only when variability exceeds a predefined threshold-to promote error detection and retention. The table below synthesizes practical trade-offs among common feedback types.

| Feedback Type | Immediacy | Cognitive Load | Ideal Use |

|---|---|---|---|

| Auditory (metronome) | High | Low | Tempo consistency drills |

| Visual (video/overlay) | Moderate | Moderate | Technical pattern correction |

| Haptic (wearables) | High | Low | Phase-specific prompts |

For applied programs, coaches should begin with baseline variability profiling to set individualized targets and progress from high-frequency, low-bandwidth feedback to reduced, outcome-focused guidance.Emphasize task-specific variability-encouraging adaptable solutions for varied lies and shot types-rather than enforcing rigid uniformity that may impede robustness. Ultimately, integrating temporal and spatial variability analysis into training promotes not only greater shot-to-shot consistency but also resilient performance under competitive and fatigue-inducing conditions.

Integrating Biomechanical Assessment with Coaching Interventions and Technology for Performance Optimization

Integrating quantitative biomechanical assessment into a coach’s decision-making framework transforms raw data into targeted interventions. High-resolution kinematic and kinetic profiles allow practitioners to move beyond generic instruction and prescribe individualized modifications that respect an athlete’s anatomical constraints and motor preferences.When interpreted through sport-specific performance models, biomechanical outputs become actionable: they identify the most efficient sequence of motion, isolate limiting segments, and reveal compensatory patterns that may increase injury risk. The collaborative translation of these findings into coaching language is essential for athlete buy-in and measurable change.

Contemporary practice leverages a suite of technologies to capture and contextualize swing mechanics; these tools complement observational coaching rather than replace it. Typical measurement modalities include: • 3D motion capture for segmental timing and joint angles, • inertial measurement units (IMUs) for on-course portability, • force plates and pressure mats for ground reaction analysis, • launch monitors for club and ball metrics, and • high-speed video for qualitative cross-checking. Each modality contributes distinct signal characteristics and error profiles, so multimodal synthesis yields the most robust interpretation.

Coaching interventions derived from biomechanical assessment should be multidisciplinary and evidence-based.Strength and conditioning programs must align with identified kinetic deficits (e.g., trunk rotational torque or lower-extremity force asymmetry), while mobility and motor-control drills address range and sequencing abnormalities. Effective programs adopt periodization principles, progressing from isolated capacity work to integrated swing-specific loading and finally to on-course transfer. Emphasis on measurable outcomes-such as changes in peak angular velocity or time-to-peak force-enables objective evaluation of intervention efficacy.

Feedback design is a core mechanism for converting biomechanical insight into durable motor learning. Use of augmented feedback can be calibrated by frequency, timing, and content: immediate visual biofeedback (e.g., real-time club path overlays) promotes rapid error correction, while faded feedback schedules encourage internalization. Coaching language and cueing should privilege an external focus when appropriate and translate complex kinetic descriptors into simple, reproducible tasks. Wearables and apps that provide concise, contextualized metrics help athletes self-monitor between supervised sessions.

Performance optimization requires iterative monitoring and risk management informed by standardized metrics and thresholds. Establish baseline distributions for key performance indicators (KPIs) such as peak trunk rotation velocity, lateral force impulse, and swing tempo, and track deviations that correlate with decreased performance or injury signals. Implement load-management protocols that adjust practice volume and intensity based on cumulative mechanical exposure. Dashboards that integrate biomechanics, wellness, and on-course outcomes facilitate adaptive coaching decisions and support longitudinal athlete development while minimizing injury risk.

Q&A

Note: The web search results provided did not return academic material relevant to golf-swing biomechanics. The following Q&A is therefore based on established biomechanical principles and peer-reviewed literature norms rather than those search results.

Q1: What is the biomechanical definition of the golf swing and which phases are commonly used in research?

A1: The golf swing is a coordinated, multi-segmental movement that transfers energy from the body to the club and ball. Researchers commonly segment the swing into address, takeaway, backswing, transition, downswing, impact, and follow-through. Precise phase definitions vary but are typically anchored to kinematic events (e.g., maximum shoulder rotation, transition initiation) and kinetic events (e.g., peak ground reaction force, impact).

Q2: What are the principal kinematic variables used to evaluate performance in the golf swing?

A2: Principal kinematic variables include segmental angular positions and velocities (thorax, pelvis, lead and trail arms, wrists), intersegmental angles (e.g., X-factor or trunk-pelvis separation), clubhead linear and angular velocity, swing plane and clubhead path, launch-lead kinematics at impact (e.g., clubhead velocity vector, face angle), and temporal sequencing (timing of peak angular velocities).

Q3: How is the kinematic sequence defined and why is it vital?

A3: The kinematic sequence describes the temporal order of peak angular velocities across segments (typically pelvis → trunk → upper arm → forearm → club). An efficient proximal-to-distal sequence maximizes angular momentum transfer and clubhead speed while minimizing energy loss. Deviations from this sequence can reduce performance and increase stress on specific joints.

Q4: Which kinetic measures are most informative for performance and injury risk?

A4: Key kinetic measures include joint moments and powers (hip, trunk, shoulder, elbow), net joint reaction forces, ground reaction forces (vertical, anterior-posterior, medial-lateral), center of pressure progression, and impulse. These quantify how forces are generated and transmitted and relate directly to ball speed and to loading that contributes to injury risk, particularly in the lumbar spine and elbow.

Q5: What neuromuscular data are typically collected and what do they reveal?

A5: Surface electromyography (EMG) from trunk, hip, shoulder, and forearm muscles is commonly recorded to determine activation onset, duration, magnitude, and patterns (phasic vs. tonic). EMG reveals muscle coordination strategies, timing relationships that support the kinematic sequence, stiffness modulation around impact, and compensatory patterns associated with fatigue or injury.

Q6: How does the X-factor (trunk-pelvis separation) relate to performance?

A6: The X-factor, the angular separation between thorax and pelvis during the backswing or at transition, is associated with potential elastic energy storage in trunk tissues and with higher subsequent rotational velocities in the downswing. Moderate-to-large X-factors often correlate with greater clubhead speed, but excessive separation or rapid recoil may increase lumbar loads and injury risk.

Q7: What is the role of ground reaction forces (GRFs) in generating clubhead speed?

A7: GRFs provide the external reaction necessary for internal joint torques and power development. Effective use of the ground (timing and direction of force application) enables sequential transfer of momentum up the kinetic chain. Early and appropriately oriented lateral-to-medial and vertical GRFs during downswing are linked to higher clubhead speeds.

Q8: Which joints and tissues are most at risk of injury in the golf swing and why?

A8: The lumbar spine, lead wrist, lead elbow (medial elbow), and shoulder are commonly at risk. Repetitive high rotational and shear forces at the lumbar spine, rapid decelerations at the wrist and forearm at impact, and extreme ranges coupled with high torques at the shoulder underlie these injury patterns. Poor sequencing, asymmetries, and inadequate strength or mobility exacerbate risk.

Q9: How should biomechanical analyses inform coaching interventions?

A9: Analyses should identify whether inefficiency arises from kinematic sequencing, inadequate force generation, poor timing, or neuromuscular deficits. Interventions can then be targeted: technical adjustments to improve sequence and club path, strength/power training to increase torque and rate of force development, mobility work to safely increase separation, and motor control training to optimize timing and reduce harmful loading.

Q10: What measurement technologies are used and what are their trade-offs?

A10: Technologies include 3D optoelectronic motion capture (gold standard for kinematics), inertial measurement units (IMUs) for field assessment, force plates and pressure mats for GRFs and center-of-pressure, high-speed video for qualitative and 2D analyses, instrumented clubheads or launch monitors for club and ball metrics, and surface EMG for muscle activity. Trade-offs involve accuracy, ecological validity, portability, cost, and complexity of data processing.

Q11: How are clubhead speed and ball launch characteristics best interpreted biomechanically?

A11: Clubhead speed is a primary performance metric reflecting the result of kinematic sequencing and power production. ball launch angle, spin rate, and launch direction depend on clubhead speed, loft, swing path, and face angle at impact. Biomechanical interpretation links these outputs to upstream mechanics (e.g., swing plane, wrist angles, timing) to inform technique changes.

Q12: What common swing faults degrade mechanical efficiency and how can they be detected biomechanically?

A12: Common faults include early release (loss of wrist lag), casting, over-swinging with poor sequencing, lateral sliding of the pelvis, and reverse pivot. Biomechanical detection relies on timing of peak segmental velocities (early peak in distal segments), reduced X-factor or premature X-factor reduction, atypical GRF patterns, and altered center-of-pressure trajectories.Q13: How do fatigue and repetition affect swing mechanics and injury risk?

A13: Fatigue alters neuromuscular control-timing delays, reduced peak force and power, and compensatory movement patterns-which can degrade performance and increase injurious loading. Chronic repetitive loading without adequate recovery promotes microtrauma, especially in the lumbar spine and medial elbow. Monitoring workload and neuromuscular markers can mitigate risk.

Q14: Are there notable differences in biomechanics across skill levels, sex, and age?

A14: Skilled golfers typically display more efficient kinematic sequencing, higher clubhead speed relative to body size, and more consistent timing. Sex differences often reflect strength and body composition variations affecting power output and clubhead speed; women and older golfers may employ different techniques (e.g., greater reliance on timing and technique) and exhibit different injury profiles. Age-related declines in strength, power, and mobility necessitate technique and conditioning adjustments.

Q15: How can strength and conditioning be specifically integrated based on biomechanical findings?

A15: Conditioning should target power development (rate of force development, rotational power), trunk stability to manage transverse plane torques, hip strength for force transmission, and forearm/wrist conditioning for impact deceleration. Exercises should be sport-specific (rotational medicine-ball throws, loaded rotational lifts, unilateral leg power) and progressive, with emphasis on neuromuscular control and transfer to swing patterns.

Q16: What statistical and analytical approaches are appropriate when studying golf-swing biomechanics?

A16: Time-series and waveform analyses (e.g., statistical parametric mapping), inverse dynamics for joint moments and powers, principal component analysis for movement pattern reduction, cross-correlation for sequencing relationships, and mixed-effects models for repeated measures and inter-individual variability are appropriate. Robust biomechanical interpretation emphasizes effect sizes, confidence intervals, and clinical/practical significance.

Q17: How should coaches and clinicians interpret group-level biomechanical findings for individual athletes?

A17: Group-level norms provide reference but must be individualized. Practitioners should assess the athlete’s specific constraints (anatomy, injury history, fitness) and goals. Use a constraint-led approach-manipulating task, surroundings, or performer constraints-to trial technique changes while monitoring objective biomechanical and performance metrics and subjective comfort.

Q18: What are practical recommendations to reduce injury risk while optimizing performance?

A18: Recommendations include: maintain appropriate mobility (thoracic rotation, hip rotation), develop trunk and hip power, train eccentric control of forearm and wrist muscles, optimize sequencing through technical drills that preserve wrist lag, implement workload monitoring and recovery strategies, and use progressive, individualized conditioning programs. Regular screening for asymmetries and early pain reporting is essential.

Q19: what are limitations of current biomechanical research on the golf swing?

A19: Limitations include small sample sizes, limited ecological validity of lab settings, heterogeneity in phase and metric definitions, reliance on cross-sectional designs, and inconsistent reporting of participant characteristics (skill level, injury history). Integration of multi-modal data (kinematics, kinetics, EMG, wearable sensors) is improving but remains methodologically challenging.

Q20: What are promising directions for future research?

A20: Future research should emphasize longitudinal and intervention designs, real-world field measurements using validated wearables, individualized modeling (musculoskeletal simulations and subject-specific inverse dynamics), machine learning for pattern recognition and injury prediction, and translational studies that assess how biomechanical interventions affect on-course performance and long-term musculoskeletal health.

Q21: How can biomechanical findings be translated into evidence-based coaching cues or drills?

A21: translate objective findings into simple, observable cues that target the underlying mechanism (e.g., “maintain wrist lag through transition” to address early release), and create drills that reproduce desired kinetics and sequencing (e.g., split-stance rotational drills, medicine-ball throws timed to downswing). Validate cues and drills by measuring their immediate and retained effects on kinematic/kinetic markers and performance outputs.

Q22: When should a biomechanical assessment be recommended for a golfer?

A22: Recommend assessment for performance plateaus, recurrent pain during/after play (particularly lumbar, wrist, elbow, shoulder), return-to-play after injury, important technique changes, or for high-performance athletes seeking marginal gains. Assessments should combine objective measurement, clinical screening, and context-specific goal setting.

If you woudl like, I can convert these Q&As into a formatted FAQ for publication, generate figures or diagrams illustrating kinematic sequences, or draft an appendix describing recommended measurement protocols (marker sets, sampling rates, EMG placement, data processing). Which would you prefer?

The Conclusion

Note: the web search results provided did not return sources relevant to golf-swing biomechanics. The following outro is an original, academically styled conclusion prepared for the requested article.

the biomechanical analysis of the golf swing presented here integrates kinematic, kinetic, and neuromuscular evidence to clarify the movement principles that underpin effective and resilient performance. Converging data identify coordinated proximal‑to‑distal sequencing, optimized ground-reaction force transfer, controlled trunk rotation (including appropriate hip-shoulder separation), and timely, high‑rate muscle activation as central determinants of clubhead speed and shot consistency. Concurrently,mechanical loads concentrated at the lumbar spine,hip,and lead shoulder underscore the trade‑offs between maximizing performance and limiting injury risk.

Translating these insights into practice requires individualized, evidence‑based interventions: technique refinements that preserve neutral spinal alignment and efficient energy transfer; targeted strength, power, and motor‑control training to augment rate of force development and stabilization; and the use of objective measurement (3‑D motion capture, force platforms, IMUs, and EMG, where feasible) to quantify deficits and track adaptation.Coaches, medical practitioners, and sport scientists should prioritize integrated assessment and periodized programs that balance performance goals with tissue tolerance and recovery strategies.

Future research should emphasize ecologically valid, longitudinal designs that link biomechanical markers to on‑course performance and injury incidence; refine musculoskeletal and neuromuscular models across age, sex, and ability levels; and exploit wearable sensing and machine‑learning approaches to enable field‑based, individualized feedback. By bridging rigorous biomechanical science with practical coaching and rehabilitation,the field can advance safer,more effective pathways for golfers to realize their performance potential.

Biomechanical Analysis of the Golf swing for Performance

Key phases of the golf swing and their biomechanical priorities

Address / Setup

Posture,balance,and joint neutrality at the address set the stage for efficient movement. A slightly flexed spine, soft knees, and centered weight distribution enable consistent rotation and effective use of ground reaction forces (GRF).

Takeaway / Backswing

Goal: Create stored elastic energy with a coordinated rotation of shoulders over a stable pelvis. Important biomechanical features:

- Torso rotation (thorax) ~ 80-100° relative to pelvis in skilled players.

- Shoulder turn creates stretch across the obliques and lats – this elastic recoil is crucial for power.

- Maintain a stable lead leg to create a platform for rotational separation (X-factor).

Transition

Goal: Convert stored energy into a sequenced downswing. The transition timing-when the lower body initiates rotation and weight shift-determines the efficiency of energy transfer up the kinetic chain.

Downswing & Impact

Peak clubhead speed is generated by sequential activation: lower body rotation, pelvis acceleration, thorax rotation, then hands and club. At impact, the body should use:

- Ground reaction forces to create vertical and lateral force vectors that contribute to ball speed.

- Proper wrist hinge release and lag to maximize clubhead speed while maintaining face control.

Follow-through

Critically important for deceleration and injury prevention.A balanced finish reflects efficient swing mechanics and proper sequencing.

Kinematics vs. Kinetics: What coaches and players must measure

Kinematics describes motion (angles, velocities, segment rotations).Kinetics describes forces and torques (GRF, joint moments). Both are crucial.

- Kinematic metrics: shoulder and hip rotation, X-factor (torso-pelvis separation), clubhead speed, swing plane angle, shaft lean, and attack angle.

- Kinetic metrics: ground reaction force peaks, rate of force development (RFD), torque at the hips and thoracic spine, and joint reaction forces at the lumbar spine and shoulders.

Major muscle groups and their roles in the swing

Understanding which muscles produce or control motion helps design training interventions that increase power and reduce injury risk.

| Muscle / group | Primary Role | Training Focus |

|---|---|---|

| Gluteus maximus & medius | Generate hip extension & stability; transfer force to torso | Hip thrusts, single-leg squats |

| Core (obliques, transverse abdominis) | Control rotation, store/release elastic energy | Anti-rotation chops, Pallof presses |

| Latissimus dorsi | Control downswing path; contribute to club acceleration | Pull variations, eccentric loading |

| Rotator cuff & scapular stabilizers | stabilize shoulder through swing and deceleration | External rotation, band work |

| Quadriceps & hamstrings | Support posture, produce GRF during weight shift | Squats, deadlifts, RFD drills |

Common swing faults and biomechanical corrections

Below is a concise mapping of frequent faults to their likely biomechanical causes and practical fixes.

| fault | Biomechanical Cause | Correction / Drill |

|---|---|---|

| Slice | Open clubface, out-to-in swing path | Inside-out path drill, impact bag, grip/face awareness |

| Hook | Closed face, excessive inside path | Path control drills, weaker grip, face-target drills |

| Early extension | Hip thrust toward ball; loss of posture | Wall drill for hip position, single-leg balance work |

| Lack of clubhead speed | Poor sequencing, low RFD, limited rotation | Medicine ball throws, plyometrics, mobility & strength |

Measurement technologies and what they reveal

Modern tools help quantify biomechanics so you can train precisely.

- Launch monitors (TrackMan, GCQuad, SkyTrak): clubhead speed, ball speed, smash factor, launch angle, spin.

- 3D motion capture: detailed kinematic data (segment rotations,angular velocities) useful for pro-level analysis.

- Force plates: measure GRF and center of pressure to analyze weight shift and RFD.

- High-speed video: affordable and effective for swing plane, impact, and sequencing inspection.

Pro tip: Combine launch monitor data with simple video to correlate swing feel with measurable outcomes-e.g., if top speed drops, check X-factor, weight shift, and wrist release timing.

Training principles: mobility, stability, strength and power

Design training with the golf swing kinetic chain in mind:

- Mobility first: thoracic rotation, hip internal/external rotation, ankle dorsiflexion. Without sufficient mobility, compensations occur.

- Stability & motor control: anti-rotation core work, single-leg balance, and scapular stability to maintain positions under load.

- Strength: build lower-body and posterior chain strength to improve GRF and force transfer.

- Power & speed-specific: medicine ball rotational throws, kettlebell swings, Olympic lift derivatives, and sprint or bounding work to increase RFD and clubhead speed.

Sample weekly microcycle (intermediate player)

- Day 1: Strength (lower body focus) + thoracic mobility

- Day 2: On-course practice + swing drills with impact focus

- Day 3: Power (medicine ball throws, plyometrics) + anti-rotation core

- Day 4: Active recovery + mobility session

- Day 5: Strength (upper body & posterior chain) + balance work

Practical drills to improve biomechanical efficiency

1. X-Factor Stretch Drill

Purpose: Increase torso-pelvis separation. Stand with feet shoulder-width, hold club across chest, rotate shoulders maximally while keeping hips quiet. Perform 3 sets of 8 slow reps focusing on end-range control.

2. Step-and-Swing (weight shift timing)

Purpose: Improve sequencing of lower body initiation. Step lead foot toward target during transition then swing through; this promotes lower-body lead and better sequencing.

3. Medicine Ball Rotational Throw

Purpose: Power development and thoracic rotation speed. Throw ball explosively from back hip through target, emphasizing rapid trunk rotation and follow-through.

Performance metrics to track for continuous betterment

- clubhead speed – key driver of distance.

- Ball speed and smash factor – efficiency of energy transfer.

- Launch angle and spin rate - influence trajectory and carry.

- Peak X-factor and rotational velocity – markers of rotational power.

- Ground reaction force symmetry and RFD – indicators of lower-body contribution.

Case study: 8-week intervention to increase clubhead speed (summary)

Participant: Male amateur, 45 yrs, baseline clubhead speed 95 mph.

- weeks 1-2: Mobility & movement quality (thoracic mobility, hip rotations). Result: better shoulder turn range.

- Weeks 3-5: Strength phase (squats, deadlifts, single-leg work). result: improved GRF and balance.

- Weeks 6-8: Power phase (med ball throws,plyo bounds,sprint efforts) + swing integration with launch monitor feedback. Result: clubhead speed increased from 95 to 101 mph, ball speed +5 mph, improved smash factor.

Data takeaway: Progressive training that targets mobility → strength → power, plus skill integration, reliably improves measurable performance (clubhead speed and ball flight).

Injury prevention: biomechanics-based considerations

Common injury sites: lumbar spine, rotator cuff, elbow (medial/lateral), and knee. Biomechanical factors that increase injury risk include:

- Excessive early extension and lumbar shear forces.

- Poor thoracic mobility leading to compensation by lumbar spine.

- Overhead deceleration deficiencies causing shoulder overload.

Preventive measures:

- Improve thoracic rotation to reduce lumbar stress.

- Build glute and core capacity to stabilize hips and pelvis.

- Use load management and periodization-avoid high-volume high-intensity swing practice without recovery.

How to use biomechanics in everyday practice

Keep it simple. Use measurable goals and technology only when it informs change. A practical workflow:

- Record baseline metrics (clubhead speed, ball speed, launch angle).

- Identify the most limiting factor (mobility,sequencing,strength).

- Implement a targeted 6-8 week plan combining gym work and swing-specific drills.

- Re-test metrics and refine program based on data.

Recommended tech stack for coaches

- affordable: High-speed phone camera + a launch monitor (SkyTrak, Mevo).

- Advanced: 3D motion capture + force plates + TrackMan/GCQuad for integrated kinetic/kinematic analysis.

Quick checklist for golfers focused on biomechanics

- Maintain a balanced, athletic address.

- Prioritize thoracic and hip mobility before power training.

- Train the glutes and core for force transfer and stability.

- practice sequencing drills-lower body leads rotation.

- Use data (clubhead speed, smash, launch) to track progress, not feel alone.

Further reading and resources

- Peer-reviewed biomechanics papers on golf swing kinematics (search terms: “golf swing biomechanics”, “X-factor rotation”, ”ground reaction force golf”).

- Coaching resources: clubfitting and launch monitor manufacturer guides for interpreting data.

- Strength & conditioning protocols specifically for golfers (NASM, TPI resources).