The modern golf swing represents a complex, coordinated motor task in which maximal performance and injury avoidance are jointly steadfast by the interaction of segmental motion, external and internal forces, and neuromuscular control.Recent increases in professional and amateur driving distances, widespread use of advanced club and ball technologies, and greater availability of biomechanical measurement tools have sharpened interest in the underlying mechanisms that govern effective and safe swing mechanics. A rigorous biomechanical outlook is thus essential to translate observable motion into engineering and physiological principles that can inform coaching, conditioning, equipment design, and rehabilitation.

Biomechanical analysis of the swing integrates three complementary domains. Kinematics describe the time-varying geometry of the golfer’s segments and the club-joint angles, angular velocities, and intersegmental coordination-typically quantified with optical motion capture, inertial measurement units, or high-speed video. Kinetics characterize forces and moments (including joint torques and ground reaction forces) that generate and transmit energy throughout the kinetic chain, frequently enough assessed with force platforms and inverse dynamics. Neuromuscular dynamics, assessed via electromyography and computational modeling, reveal muscle activation patterns, timing, and the role of eccentric-concentric sequencing in producing rapid rotation and deceleration. Together these measures enable decomposition of performance into measurable determinants such as proximal-to-distal sequencing, pelvis-torso separation (X-factor), and temporal patterns of force application.

Empirical findings converge on several consistent principles that underpin effective swing mechanics: (1) a proximal-to-distal kinematic sequence that optimizes angular momentum transfer from the hips through the torso and into the upper limbs and club; (2) coordinated generation and application of ground reaction forces to create a stable base and augment segmental angular velocities; and (3) precise neuromuscular timing that balances rapid concentric drives with controlled eccentric braking to manage clubhead path and impact dynamics. Variability in these factors accounts for a large proportion of interindividual differences in clubhead speed, ball launch conditions, and shot dispersion, and highlights the need for individualized technical refinement rather than one-size-fits-all prescriptions.

Concurrently, specific loading patterns inherent to high-velocity, repetitive rotational tasks place golfers at elevated risk for overuse and acute injuries, especially to the lumbar spine, shoulder complex, and medial elbow. Biomechanical analyses identify modifiable contributors to injury risk-excessive lumbar shear and extension moments, maladaptive sequencing that increases distal segment loads, and asymmetrical force application-thereby informing prevention strategies that combine technique modification, targeted strength and mobility training, and equipment optimization. This article synthesizes contemporary biomechanical evidence on kinematics, kinetics, and neuromuscular control of the modern golf swing, with the dual aims of supporting evidence-based coaching interventions to enhance performance and delineating practical measures to mitigate injury risk.

Kinematic Sequencing and temporal Coordination of segments in the Modern golf Swing: Assessment Methods and Practical Coaching cues

Kinematic sequencing in the contemporary swing is best conceptualized as a proximal‑to‑distal cascade of angular motion: pelvis → trunk → upper arm → forearm → club. This cascade is a kinematic construct-concerned with the geometry and timing of motion rather than the forces producing it-consistent with standard distinctions between kinematic (motion-focused) and dynamic (force‑focused) analyses. Quantifying the sequence requires time‑resolved measures of segment rotations and angular velocities to identify the temporal order, overlap, and lag between adjacent segments; these parameters form the basis for linking movement patterns to ball speed, accuracy, and injury risk.

Robust assessment combines laboratory and field tools to capture both high‑resolution timing and ecological validity. Common methods include:

- 3D motion capture – gold standard for segment kinematics and intersegmental timing.

- inertial measurement units (imus) - portable measurement of segment angular velocity and timing for on‑range monitoring.

- High‑speed video - qualitative and semi‑quantitative sequencing analysis accessible to coaches.

- Force plates and pressure insoles – temporal profile of ground reaction forces to link lower‑body initiation to upper‑body sequencing.

- Launch monitors and radar - provide performance correlates (clubhead speed, ball speed, smash factor) to validate kinematic improvements.

Translating assessment into practice requires concise, evidence‑based cues and progressive interventions. Practical coaching cues that target the temporal chain include:

- “Initiate with the ground” – emphasize early lateral weight transfer and hip rotation to start the proximal drive.

- “Clear the hips before the shoulders” – teach pelvis rotation to precede thorax rotation, preserving trunk‑to‑arm X‑factor timing.

- “Hold the lag” – cue maintenance of wrist lag to delay peak clubhead speed until the late downswing.

- “Feel the whip” - encourage rapid distal release following proximal acceleration, reinforcing correct timing rather than pure force.

| Tool | Key metric | Coaching application |

|---|---|---|

| 3D motion capture | Segment time‑to‑peak (ms) | Diagnose sequencing deficits objectively |

| IMUs | Angular velocity profiles | On‑course monitoring & biofeedback |

| High‑speed video | Qualitative sequence checkpoints | Accessible technician‑level feedback |

| Force plate | Onset of push‑off / GRF timing | Train ground‑up initiation patterns |

Integrating these objective measures with succinct cues and progressive drills enables targeted adjustments to timing and coordination, improving transfer of kinematic sequencing changes to measurable performance gains.

Ground Reaction Forces and Joint Kinetics: Translating force Production into Ball Speed and Consistency

Ground reaction forces (GRFs) act as the distal foundation for proximal power transfer during the swing. Vertical and shear components measured under each foot govern net impulse, center-of-pressure progression, and the timing of pelvis-thorax separation. Empirical force-plate studies indicate that controlled increases in vertical GRF during the transition and downswing are synchronized with pelvic rotation acceleration, while medial-lateral GRFs modulate lateral weight shift and balance. these force signatures are not simply peak values but time-dependent waveforms: the rate of force growth and the timing of force transfer between feet are as important for speed and repeatability as absolute magnitude.

Joint kinetics describe how those external forces create internal moments and joint powers across the lower limb and trunk. The pattern typically observed is a proximal escalation of net joint moment and power: the ankle provides early stabilizing moments, the knee contributes positive extension moments in late downswing, and the hip produces large propulsive and rotational moments that feed into trunk and shoulder segments. The following table summarizes qualitative kinetic contributions commonly reported in biomechanical analyses.

| Region | Relative Kinetic Role | Typical Timing (relative to impact) |

|---|---|---|

| Ankle | Stabilization / shear control | Early downswing → transition |

| Knee | Extension power & weight transfer | Late downswing → pre-impact |

| Hip | Primary propulsion & rotational torque | Peak in late downswing → early impact |

Translating kinetic outputs into ball speed and shot-to-shot consistency requires attention to both magnitude and coordination. Key determinants include: timing alignment of peak joint power with peak clubhead velocity, minimization of inter-trial variability in centre-of-pressure trajectory, and efficient proximal-to-distal sequencing. Practical targets for coaches and athletes can be summarized as follows:

- Increase rate of force development in the downswing without sacrificing balance (plyometrics and resisted swings).

- Reduce lateral shear variability through stance and foot-pressure drills to improve repeatability.

- Emphasize hip torque timing with rotational drills that couple pelvis drive to trunk lag release.

From an injury-prevention and optimization perspective, kinetic analysis informs load management strategies. High peak GRFs concentrated on a single limb or abrupt shear spikes are correlated with overuse symptoms at the knee and lumbar spine; conversely, distributed impulse and smoother force transitions reduce internal joint stress. Monitoring frameworks that combine force-plate metrics (peak GRF, impulse, COP path) with wearable inertial sensors allow clinicians to identify asymmetries and prescribe targeted eccentric strengthening, mobility work, and motor-control interventions. In applied settings, the goal is a reproducible kinetic profile that maximizes energy transfer to the clubhead while maintaining joint loads within tissue-tolerance limits.

Trunk Rotation, Pelvic Mechanics, and Lumbar Load Management: Balancing Power Generation and Spinal Health

Coordinated axial rotation between the thorax and pelvis is the principal driver of clubhead speed, but it is also the key locus of cumulative spinal loading when poorly timed. kinematic sequencing that emphasizes distal-to-proximal energy transfer-hips initiating rotation, followed by pelvis, torso, and finally the shoulders and arms-minimizes peak lumbar shear and compressive impulses. Quantitatively, maintaining a controlled transverse-plane dissociation (pelvis lag of 10-20° relative to the thorax at transition for many skilled golfers) preserves elastic energy in the obliques and multifidus while avoiding abrupt trunk deceleration that spikes lumbar load. From a biomechanical perspective, therefore, power optimization requires modulation of rotational velocity and timing rather than maximal rotation magnitude alone.

Pelvic mechanics are central to both power generation and spinal health: the hips must supply rotational torque while the lumbopelvic region functions as a stiff, load-transferring link. Key observable markers of effective pelvic behavior include:

- Progressive weight transfer from trail to lead limb during transition to facilitate hip torque.

- Lead-hip external rotation and clearance to allow pelvis rotation without compensatory lumbar side-bending.

- Controlled sacroiliac motion to dissipate rotational forces through the pelvis rather than the lumbar vertebrae.

Lumbar load management must account for interaction of posture, rotation, and force application. Increased forward flexion, lateral bending, or asymmetric muscle activation elevates discal shear and compressive loads during the downswing-particularly at transition and impact. The simple comparative table below summarizes typical rotational states and the associated relative lumbar loading seen across common swing phases in performance testing:

| Phase | Typical Trunk Rotation (°) | Relative Lumbar Compression |

|---|---|---|

| Top of Backswing | 60-90 | Low-Moderate |

| Transition | Rapid reversal | Moderate-High |

| Impact | Reduced vs. top (~30-50) | High |

Practical implications for coaching and conditioning follow directly from these mechanics: emphasize hip mobility and power (glute and hip rotator capacity), targeted trunk motor control (anti-rotation endurance of the obliques and TVA), and graded exposure to high-velocity rotational loads. Movement-based cues that prioritize smooth sequencing and lead-hip clearance reduce compensatory lumbar strategies. Evidence-informed training priorities include: progressive rotational power drills, hip-centric mobility protocols, and segmental motor-control exercises that reproduce swing-specific loading while limiting peak spinal impulses during skill acquisition and return-to-play progressions.

Upper Extremity Kinetics and Club Interface: Shoulder,Elbow,and Wrist Contributions to Club path and Impact Stability

The proximal shoulder complex functions as the primary generator and transmitter of angular momentum to the distal segments and the club. Peak internal rotation torque about the glenohumeral joint occurs during late downswing,produced largely by the **pectoralis major**,**latissimus dorsi**,and internal rotators of the shoulder,while the rotator cuff provides stabilizing compressive forces to maintain the humeral head within the glenoid. Kinematic sequencing-characterized by a proximal-to-distal gradient of angular velocities-ensures that shoulder-generated power is conveyed efficiently down the kinetic chain. Excessive translational shear at the shoulder or delayed scapular retraction reduces effective moment arm length and degrades club path consistency, evidenced by increased lateral dispersion and altered face-to-path angle at impact.

Distal to the shoulder, the elbow acts as a dynamic linker that modulates lever length and timing of energy transfer. Controlled elbow extension contributes to increasing the distal radius of rotation and thus clubhead linear velocity, while premature or late extension changes the club arc and can introduce radial deviations in club path. The joint moment about the elbow is principally managed by the **triceps brachii** and forearm musculature through coordinated eccentric-concentric transitions; co-contraction patterns here are critical for damping unwanted oscillations of the shaft. From a control-theoretic perspective, the elbow provides a phase-dependent impedance element that shapes both amplitude and timing of the distal velocity profile.

Wrist mechanics have an outsized influence on face orientation and impact stability because small angular adjustments at the wrist produce large changes at the clubhead. Maintenance of an optimal wrist-**** (radial/ulnar deviation and flexion/extension balance) facilitates consistent toe-up/toe-down trajectories and controlled release timing; moreover, forearm **supination/pronation** couples with wrist extension to orient the face during the final 100-150 ms before impact. Practical considerations for performance and injury mitigation include:

- Grip force modulation: sufficient to prevent slippage but low enough to allow passive release mechanics.

- Wrist stiffness: tuned via co-contraction to stabilize impact without impairing clubhead speed.

- Forearm flexibility: to permit rapid pronation without compensatory shoulder or elbow motion.

These elements collectively determine micro-variability in face angle and the extent of shot dispersion under varying shot demands.

| Joint | Relative Peak Moment | Primary Muscles | Functional Role |

|---|---|---|---|

| shoulder | High | Pectoralis,Latissimus,Rotator cuff | Power generation,proximal stabilization |

| Elbow | Moderate | Triceps,Biceps,Forearm flexors | Lever modulation,timing/damping |

| Wrist | Low-Moderate | Wrist extensors/flexors,Pronators | Face control,release & impact stability |

At the club interface,grip mechanics translate joint kinetics into clubhead kinematics through normal and tangential forces at the handle. Effective impact stability emerges from the interplay of distal stiffness (wrist/elbow co-contraction), precise timing of wrist uncocking, and minimal extraneous pronation/supination immediately pre-impact. Training interventions should thus target both maximal torque production at the shoulder and fine motor control of wrist/elbow stiffness to optimize club path fidelity and reduce the incidence of impact-related injuries.

Neuromuscular Activation patterns and Motor Control Strategies: EMG Insights and Drills for Optimizing Sequencing

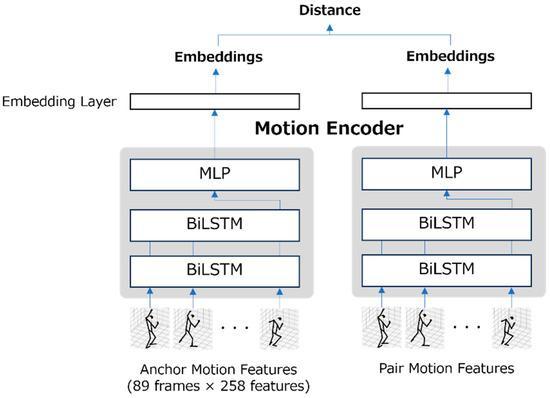

Electromyographic (EMG) analyses of the modern swing consistently reveal a proximal‑to‑distal activation cascade: early pre‑activation in the hips and pelvis is followed by sequenced recruitment of the trunk rotators and then the shoulder and forearm musculature. This temporal ordering supports efficient transfer of angular momentum and reduces dissipative energy leakage at segment interfaces. Quantitative EMG markers-onset latency, relative amplitude (%MVC), and rate of rise-provide objective indices of sequencing quality and can distinguish effective power transfers from compensatory, injury‑prone strategies.

Typical phasic patterns emphasize a burst in the trail gluteus maximus and ipsilateral hamstrings at downswing initiation, rapid concentric activation of obliques and erector spinae through mid‑downswing, and maximal activation of the lead latissimus/pectoralis and forearm flexors at and just after impact. The simplified table below condenses representative EMG findings observed across cohort studies and lab models; values are illustrative and intended as coaching‑relevant heuristics rather than fixed norms.

| Phase | Primary muscles | Onset (ms rel. to downswing) | Relative amplitude |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pre‑downswing | Gluteus maximus, hamstrings | −80 to −40 | 20-40% MVC |

| Mid‑downswing | external oblique, erector spinae | −20 to +10 | 40-70% MVC |

| Impact | Pectoralis major, forearm flexors | 0 to +30 | 60-100% MVC |

From a motor‑control perspective, effective sequencing reflects integrated feedforward planning and adaptive feedback tuning. High‑level strategies include predictive timing to exploit stretch‑shortening cycles and intersegmental coordination to minimize counter‑torques.Training should emphasize variability‑rich practice to foster robust internal models while avoiding excessive co‑contraction that elevates joint loading. Objective monitoring-via surface EMG, inertial sensors, or validated wearables-permits phase‑specific feedback and quantification of neuromuscular efficiency.

Applied drills derived from EMG insights are straightforward, progressive, and cue‑driven:

- Medicine‑ball rotational throws (single‑leg and double‑leg) to emphasize early hip drive and trunk rotation timing;

- Step‑through swings to encourage lead‑leg deceleration and proximal initiation;

- Slow‑motion segmented swings with pause at transition to train onset latencies;

- Towel‑snap impact drills to promote distal activation at impact while preserving trunk sequencing;

- Resisted rotational band work focusing on explosive release to enhance rate of EMG rise.

Couple these drills with simple biofeedback (metronome, real‑time EMG indicators, or inertial cadence targets) and progress by reducing external constraints to reintroduce task variability and consolidate efficient motor patterns.

Injury Risk Profiling and Preventive interventions: Screening, Conditioning, and Technique Modifications for Common Pathologies

Risk stratification should integrate clinical history, functional screening, and objective biomechanical metrics to produce an individualized injury risk profile. Clinical datasets (prior injury, pain patterns during the swing, practice volume) are combined with kinematic and kinetic variables such as **pelvis-thorax separation (X‑factor)**, peak lumbar lateral bending, and peak ground reaction forces to quantify tissue loads and exposure. Epidemiologic sources identify the lumbar spine and upper extremity as high‑prevalence sites in golfers; therefore, profiling must prioritize measures that reflect both repetitive micro‑trauma and single‑event overload mechanisms.

A standardized screening battery facilitates early detection of deficits that predispose to pathology. Core components include:

- Patient-reported outcome and load-history (hours per week, practice intensity)

- Range of motion tests (hip internal rotation, thoracic rotation)

- Strength and endurance assessments (rotator cuff, scapular stabilizers, posterior chain, trunk endurance)

- Neuromuscular control and dynamic balance (single‑leg squat, reactive balance during perturbation)

- Biomechanical swing analysis (3D or high‑speed video to identify harmful patterns such as excessive lateral flexion or early extension)

Each element should be scored against normative and performance-based thresholds to flag athletes requiring targeted intervention.

Preventive interventions must be evidence‑based, progressive, and task‑specific. Conditioning priorities include restoration of hip and thoracic mobility, **eccentric strengthening** of the medial and posterior shoulder, posterior chain capacity (hip extension and trunk control), and sport‑specific neuromuscular drills that emphasize deceleration and sequencing. Technique modifications-such as reducing excessive lateral flexion during transition, moderating backswing depth, or adjusting weight shift-are implemented only after underlying mobility or strength deficits are addressed. Central to all programs is **load management**: periodized practice, purposeful recovery strategies, and graded return‑to‑play criteria guided by objective performance metrics.

| Common Pathology | Key Screening Marker | Preventive Intervention |

|---|---|---|

| Low back pain | Reduced lumbar endurance; excessive lateral bending | core motor control, posterior chain strengthening, technique to reduce lateral load |

| Medial epicondylalgia | Reduced eccentric wrist flexor capacity | Eccentric wrist training, grip load progression, swing release timing |

| Shoulder impingement | Rotator cuff weakness; poor scapular control | Scapular stabilizer strengthening, thoracic mobility, adjusted swing arc |

Ongoing monitoring with repeat screening and biomechanical reassessment ensures interventions remain aligned with the athlete’s evolving risk profile and performance goals.

Integration of Biomechanical Analysis into Coaching Practice: Technology Use, Data Interpretation, and Evidence Based Training Protocols

Contemporary coaching increasingly relies on the convergence of multiple measurement systems to form a coherent assessment of a player’s swing. Technologies such as high‑speed video, 3D marker‑based motion capture, markerless camera systems, inertial measurement units (IMUs), force plates, and launch monitors each contribute distinct, complementary data streams. Integration here means the systematic process of combining these streams so that kinematic, kinetic and ball‑flight data are temporally and spatially aligned, enabling coaches to link movement patterns to performance outcomes rather than treating each metric in isolation. Effective integration requires calibrated protocols,synchronized sampling rates,and documented workflows so that measurement error is minimized and findings are reproducible across sessions.

Interpreting biomechanical output demands rigor: coaches must prioritize **Validity** (dose the device measure what it claims?) and **Reliability** (are measurements consistent across trials and conditions?). Signal processing choices-filter cutoffs,downsampling,and marker smoothing-directly affect derived variables such as segmental angular velocity or ground reaction force peaks. Interpretation should therefore be grounded in statistical descriptors (means, variances, confidence intervals) and practical effect sizes rather than single‑trial anecdotes. When comparing an athlete to reference norms, emphasize within‑subject change and clinically meaningful thresholds to avoid overgeneralizing population averages to individual coaching decisions.

Translating analysis into training requires evidence‑based protocols that respect motor learning and physiological adaptation. Typical intervention components include mobility sequencing,targeted strength/power development,and technique drills that manipulate constraints to shape motor solutions. Best‑practice coaching workflows commonly follow these steps:

- Assess – baseline biomechanical and performance testing;

- Interpret – link deficits to specific mechanical causes;

- Prescribe – prioritized, measurable interventions with progression rules;

- Monitor – repeat testing at pre‑defined intervals to quantify adaptation.

Each prescribed change should have an associated hypothesis (mechanical rationale) and objective metric for evaluation so that interventions remain accountable and iteratively refined.

Practical implementation also involves cost‑benefit and ethical considerations: data governance, athlete consent, and clear interaction of uncertainty to stakeholders. Below is a concise reference table coaches can use when selecting technology according to practice goals and resource constraints. Embedding biomechanical analysis into routine coaching elevates decision making from intuition‑based to evidence‑guided, provided the coach maintains competence in both technique and data literacy.

| Technology | Primary Output | Recommended Use |

|---|---|---|

| IMU | Segment angular velocities | Field screening,swing phase timing |

| Force Plate | Ground reaction forces | Weight transfer and power profiling |

| 3D Motion Capture | Joint kinematics (high fidelity) | Detailed technique diagnosis,research |

Q&A

Note on search results: The web search results provided with the request concern mobile apps and device support and are not relevant to biomechanical literature on the golf swing. The Q&A below is therefore constructed from accepted principles and peer-reviewed trends in biomechanics, motor control, and sports medicine rather than from those search results.

Q&A: Biomechanical Analysis of the Modern Golf Swing

1) What is meant by “biomechanical analysis” of the modern golf swing?

Answer: Biomechanical analysis of the golf swing is the systematic study of the motion (kinematics), forces and moments (kinetics), and underlying neuromuscular control that produce the golfer’s movement. It applies mechanical and physiological concepts to quantify how body segments, joints, muscles, and the ground interact to generate clubhead trajectory, ball launch conditions, and to identify movement inefficiencies or injury mechanisms.

2) What are the primary phases of the modern golf swing used in biomechanical analysis?

Answer: The swing is commonly divided into address (setup), backswing (early and late), transition, downswing (early and late), impact, and follow-through. These divisions facilitate temporal alignment of kinematic variables (e.g., peak trunk rotation) and kinetic events (e.g., peak ground reaction forces) across trials and subjects.3) Which kinematic variables are most informative for performance and coaching?

Answer: Key kinematic variables include:

– Segmental rotations and angular velocities of pelvis, thorax (upper trunk), shoulders, and lead arm.

– X-factor (relative trunk-to-pelvis rotation) and X-factor stretch (differential rotation between pelvis and thorax early in downswing).

– Sequencing/timing of peak angular velocities (kinematic sequence).

– Clubhead speed and path, wrist hinge (cocking) angles, and swing plane angles.

– Lower-limb joint angles (hip/knee/ankle) and spinal curvature. These quantify how energy is produced, transferred, and delivered to the club.

4) What kinetic measures are important and how do they relate to performance?

Answer: Important kinetic measures include:

– Ground reaction forces (GRFs) and net joint moments (especially hip and trunk).

- Joint torques and power (hip, trunk, shoulder, elbow, wrist).

– Intersegmental forces and impulse (contribution of lower body and trunk to clubhead speed).

Higher peak proximal-to-distal power transfer and optimized GRF patterns (timely lateral-to-medial and vertical force application) are associated with greater clubhead speed and ball velocity.

5) What is the “kinematic sequence” and why does it matter?

Answer: The kinematic sequence describes the timing order in which peak angular velocities occur across body segments: typically pelvis → trunk → lead arm → club. A proximal-to-distal sequence maximizes transfer of angular momentum and results in greater clubhead speed with reduced local joint loading. Deviations (e.g.,early arm acceleration or delayed pelvis rotation) reduce efficiency and may increase injury risk.

6) How do neuromuscular dynamics influence swing execution?

Answer: Neuromuscular control governs the timing,magnitude,and coordination of muscle activation patterns driving the kinematic and kinetic outputs. Key aspects include:

– Pre-programmed activation patterns for sequencing.

– Eccentric-to-concentric muscle actions for X-factor stretch and elastic energy storage (especially in trunk rotators and hip musculature).

– Reflexive stabilization to manage high-speed trunk rotation and deceleration, protecting the lumbar spine and shoulder.

Training that targets coordination, rate of force development, and intermuscular timing can improve swing efficiency.

7) What measurement technologies are used in contemporary biomechanical analyses?

Answer: Common tools include:

- Optical motion capture (marker-based) for high-accuracy 3D kinematics.

– Inertial measurement units (IMUs) for field-based kinematics.

– Force plates or pressure insoles for GRFs and centre of pressure.

– electromyography (EMG) for muscle activation timing and amplitude.

– High-speed video and radar/launch monitors for club and ball kinematics.

Multimodal setups combining these modalities yield the most comprehensive analyses.

8) Are there normative or reference values for key metrics (e.g., X-factor, clubhead speed)?

Answer: Normative values vary by skill level, sex, and age, but general trends are:

– Clubhead speed: recreational male golfers frequently enough ~70-95 mph, elite males ~110-125+ mph; female values are lower correspondingly.

– X-factor: typical ranges are 20-45 degrees of relative separation between pelvis and thorax at top of backswing; greater X-factor is associated with higher potential for clubhead speed but must be balanced with mobility and spinal health.

– Kinematic sequence: optimal proximal-to-distal timing with consistent temporal spacing between peak angular velocities.

These ranges are guidelines; individual assessment is necessary.

9) What biomechanical patterns are associated with increased injury risk?

Answer: Patterns linked to injury include:

– Excessive or repeated lumbar extension-rotation under high loads (risk for low back pain).

– Poor pelvic sequencing or “reverse” kinematic sequence that increases stress on the lead shoulder and elbow.- Excessive lateral bending (side-bend) or early extension during transition, increasing lumbar shear and facet loading.

– High joint torques without adequate neuromuscular control or tissue capacity (e.g., inadequate hip mobility leading to compensatory lumbar motion).

Screening and corrective conditioning can mitigate these risks.

10) How can biomechanical analysis guide technique refinement?

Answer: Objective measurements identify inefficient mechanics (e.g., early arm acceleration, insufficient pelvis rotation, poor sequencing). Interventions include:

– Motor learning approaches to alter timing (e.g., tempo drills, augmented feedback).

– Mobility interventions for thoracic rotation and hip range.

– Strength and power training targeting hip extensors, trunk rotators, and posterior chain to increase force capacity.- Constraint-led practice that manipulates task or environment to encourage desired mechanics.

Data-driven coaching prioritizes the smallest technique change that yields measurable performance gain while minimizing injury risk.11) What training or rehabilitation interventions are supported by biomechanical evidence?

Answer: Effective interventions include:

– Strength and power programs focusing on hip extensors,gluteals,and trunk rotators to increase force transfer.

– eccentric and stretch-shortening cycle training to enhance elastic energy storage and X-factor stretch recoil.

– Thoracic mobility and hip internal rotation exercises to permit safe X-factor magnitude.

– Neuromuscular control drills and progressive exposure to swing speeds to improve timing and deceleration mechanics.

– Individualized rehabilitation addressing specific deficits identified in assessment (e.g.,hip abductor weakness linked to swing instability).

12) What are practical assessment protocols for clinicians and coaches?

Answer: A practical protocol integrates:

– Baseline screening: joint range of motion (thoracic rotation,hip internal/external rotation),trunk endurance,and strength tests.- Field-based swing capture: IMUs or high-speed video to quantify clubhead speed,kinematic sequence,and X-factor.

– Laboratory assessments if available: motion capture, force plates, and EMG to quantify kinetics and muscle activation.

– Functional tests: single-leg balance, rotational medicine ball throws to assess force transfer and sequencing.

Combine assessments to form individualized training and technical prescriptions.

13) What are common limitations and pitfalls in biomechanical golf research?

Answer: Limitations include:

- Between-study variability in definitions (e.g., how X-factor is measured), making comparisons difficult.

– Laboratory conditions (marker-based capture, barefoot on force plates) may not perfectly replicate on-course dynamics.

– Small sample sizes and heterogeneous participant skill levels reduce generalizability.

– Overemphasis on isolated metrics (e.g., maximizing X-factor) without considering tissue capacity and injury risk.

Future work should prioritize standardized protocols, larger cohorts, and longitudinal designs linking mechanics to performance and injury outcomes.14) How should coaches balance performance gains with injury prevention?

Answer: Coaches should:

- Use progressive training to increase tissue capacity before asking athletes to produce higher torques or speeds.

– Favor technically efficient solutions (optimal sequencing) over simply increasing rotation magnitude.

– Monitor load (practice volume and intensity) and restore mobility/strength deficits proactively.

– Employ objective tracking (e.g., swing-speed progression, pain/soreness scales) to detect maladaptive trends early.

15) What are promising directions for future research?

Answer: Important directions include:

– Longitudinal studies linking biomechanical markers to injury incidence and career longevity.

– Integration of wearable sensor data for ecologically valid, in-field monitoring of swing mechanics and training load.

– Machine learning approaches to identify subtle patterns predictive of injury or performance plateaus.

– Interdisciplinary interventions combining biomechanics, motor learning, and individualized conditioning to determine optimal training prescriptions.

16) How can a practitioner implement biomechanical findings in an evidence-based coaching plan?

Answer: Steps:

– Conduct a targeted biomechanical and physical assessment.

– Identify 1-3 primary deficits: mobility, strength/power, or timing/coordination.- Prioritize interventions that address the limiting factor and are supported by data (e.g., thoracic mobility plus tempo drills if X-factor is constrained).

– Use objective metrics to monitor progress (clubhead speed, kinematic sequence timing, pain scores).

– Adjust techniques based on measured responses, balancing immediate performance and long-term tissue health.

17) What are key takeaways for researchers, clinicians, and coaches?

Answer: biomechanical analysis provides actionable insight into how the golf swing produces performance and injury risk. The most efficient swings use a coordinated proximal-to-distal sequence,appropriate mobility and strength,and controlled transfer of force from the ground through the trunk to the club. Evidence-based interventions combine technique modification, motor learning principles, and targeted physical conditioning. Objective measurement and individualized programming are essential for maximizing performance while minimizing injury.

If you would like, I can:

– Generate a one-page clinician’s checklist for field assessment and intervention.

- Create sample structured drills and progressive training blocks tied to specific biomechanical deficits.

– Draft a short methods template for collecting swing kinematics and kinetics in a lab or field setting.

biomechanical analyses of the modern golf swing synthesize kinematic patterns, kinetic loading, and neuromuscular coordination to explain how elite performance is produced and how injury risk emerges. Characteristic features-timed separation of pelvis and thorax rotation, efficient transfer of angular momentum through the kinetic chain, targeted ground-reaction forces, and precise neuromuscular sequencing-consistently distinguish effective from inefficient swings. When interpreted together, these domains provide a mechanistic framework that links technique to ball-flight outcomes and to the distribution of tissue loads that predispose golfers to common overuse and acute injuries.

for practitioners and applied researchers, the evidence supports several pragmatic directions: prioritize coordinated proximal-to-distal sequencing and controlled dissociation of the trunk and hips in technical coaching; incorporate force- and velocity-based metrics into strength and conditioning to develop sport-specific power while minimizing harmful shear and torsional loads; and use neuromuscular retraining and movement variability strategies to improve robustness under performance stress. Translational tools – including validated wearable sensors and standardized motion-capture protocols - can facilitate real-world monitoring and individualized interventions, bridging laboratory insights and on-course implementation.

Caveats remain. The current literature is limited by methodological heterogeneity (varying definitions of phases, diverse measurement systems, and predominantly cross-sectional designs), underrepresentation of female and older golfers in many cohorts, and incomplete integration of fatigue, psychology, and equipment interactions. Future work should emphasize longitudinal and interventional trials, greater ecological validity through in-field measurement, multimodal modeling that combines biomechanics with tissue mechanobiology, and consensus on outcome metrics to enable meta-analytic synthesis.By integrating rigorous biomechanical assessment with individualized coaching and clinically informed conditioning, stakeholders can refine technique to enhance performance while mitigating injury risk. Continued multidisciplinary collaboration among biomechanists, clinicians, coaches, and technologists will be essential to translate emerging evidence into scalable, athlete-centered practice.

Biomechanical Analysis of the Modern Golf Swing

Key concepts and SEO keywords to no

Understanding the modern golf swing requires grasping a small set of high-impact concepts that drive clubhead speed, ball striking, and consistency. use these keywords while reading or searching for drills,training,or analysis:

- golf swing biomechanics

- Kinematic sequence

- Ground reaction forces (GRF)

- X‑factor and separation angle

- Clubhead speed and ball spin

- Swing tempo and timing

- Launch monitor and motion capture data

H2: The biomechanical phases of the modern golf swing

The golf swing can be broken into distinct phases. Each phase has specific biomechanical goals that,when executed in sequence,maximize power transfer and consistency.

Address / Setup

- Neutral spine angle and athletic posture to allow rotation.

- Proper grip pressure (firm but not tense) for clubface control.

- Foot positioning to enable stable ground reaction force application.

Backswing

- Rotate the torso while maintaining a stable lower body; create the X‑factor (separation between shoulders and hips).

- Load eccentrically into the trail leg-this stores elastic energy for the downswing.

- maintain wrist hinge for potential energy stored in the club.

Transition & Downswing

- Start the downswing with lower-body initiation (pelvic rotation and lateral shift), followed by torso, arms, and club-this is the kinematic sequence.

- Generate ground reaction force (GRF) by pushing into the lead leg to create upward and rotational forces.

- Maintain lag (wrist angle) to maximize clubhead speed at release.

Impact

- Achieve optimal clubface alignment and center contact (sweet spot).

- Transfer stored energy into the ball through synchronized body and club motion.

- Control loft and spin via attack angle and dynamic loft.

follow-through

- Allow natural deceleration; a full follow-through indicates efficient energy transfer.

- Maintain balance and posture to facilitate repeatability.

H2: Kinematic sequence – the core of swing mechanics

The kinematic sequence describes the order and timing of segmental rotations: pelvis → torso → upper torso/shoulders → arms → club. Efficient golfers show a consistent proximal-to-distal sequence that produces maximal clubhead speed while minimizing energy leaks.

Key measurable features

- Peak pelvic rotation velocity occurs first.

- Peak thorax rotation velocity follows.

- Arm and club peak velocities occur last-creating a whip effect.

poor sequencing (e.g., early arm dominance) reduces clubhead speed and increases inconsistency. Use video and motion capture to quantify timing intervals (milliseconds) between peaks.

H2: Ground reaction forces and center of pressure

Modern biomechanical analysis emphasizes how golfers use the ground. Force plates reveal how players load and unload each foot to create torque and vertical impulse.

- Backswing: increased load on the trail foot (stores energy).

- Transition: lateral shift toward the lead foot with rotational push to create GRF that accelerates the pelvis and torso.

- Impact: force directed into the ground (vertical and horizontal components) contributes to launch angle and spin.

H2: Common swing faults from a biomechanical viewpoint

Identifying the mechanical cause of common faults helps design targeted drills and conditioning.

Overactive upper body / early arm release

- Cause: Lack of pelvic drive or poor sequencing.

- Effect: Loss of lag, reduced clubhead speed, inconsistent strikes.

- Fix: Lower-body initiation drills and resisted rotation work.

Reverse spine angle / sway

- Cause: Hip mobility limitations or poor setup.

- Effect: Inconsistent impact plane and mishits.

- Fix: Mobility drills for hips and thoracic spine; posture re‑checks.

Early extension

- cause: Weak glutes or poor hip mobility.

- Effect: Loss of spine angle and inconsistent contact.

- Fix: Strengthening glute medius/maximus and patterning hip hinge in drills.

H2: Measuring performance – useful metrics

Combine biomechanical testing and launch monitor metrics to get a full picture:

| Metric | What it tells you | Typical goal |

|---|---|---|

| Clubhead speed | raw power potential | Increase with power training |

| Smash factor | Ball speed ÷ clubhead speed (efficiency) | Maximize with center contact |

| Kinematic sequence timing | Order and timing of segment peaks | Proximal-to-distal pattern |

| Ground reaction forces | How you use the ground for power | Consistent lead foot force at impact |

H2: Training interventions – mobility, strength, and motor control

A biomechanically optimized swing comes from three pillars: mobility, strength/power, and motor control. Below are practical recommendations.

Mobility

- Thoracic rotation drills - improve upper-body turn without compensating with the lumbar spine.

- Hip internal/external rotation work – facilitates pelvic drive and reduces early extension.

- Ankle dorsiflexion exercises - helps maintain posture and balance during weight shift.

Strength & Power

- hip hinge and deadlift variations for posterior chain strength.

- Rotational medicine ball throws to develop explosive torso rotation.

- Single-leg strength work to improve balance and GRF application.

Motor control & sequencing

- Slow-motion rehearsal with emphasis on lower-body initiation.

- Downswing initiation drills (step drills, one-leg drills) to train timing.

- Repetition with feedback (video, coach, or launch monitor) to reinforce the correct kinematic sequence.

H2: Technology for swing analysis

Use objective tools to measure biomechanics and track betterment:

- 3D motion capture: Provides joint angles, velocities, and kinematic sequencing.

- Force plates: Measure ground reaction forces and center of pressure shifts.

- Inertial Measurement Units (IMUs): Portable sensors that give rotational velocities and tempo data.

- Launch monitors (TrackMan, FlightScope): Deliver ball speed, launch angle, spin, and smash factor.

How to combine data

Overlay kinematic sequencing from motion capture with launch monitor outcomes (carry distance, spin) and force-plate data to see which mechanical changes produce meaningful ball-flight improvements. For example,improved pelvic drive on force-plate data shoudl coincide with increased clubhead speed and improved smash factor if sequencing and contact are correct.

H2: Practical drills and progressions

Below are concise drills that address common biomechanical deficits.

Pelvic-Lead Drill (Timing)

- Setup in address, make a small half-backswing.

- On the downswing,step slightly with the lead foot while rotating the pelvis toward the target.

- Goal: Feel pelvis lead the torso to create correct kinematic sequencing.

Lag Preservation Drill (Power)

- Make slow swings maintaining wrist hinge longer.

- Release only through the ball-do not scoop.

- Goal: Increase stored energy and late release to boost clubhead speed.

Ground Force Awareness Drill (Balance & GRF)

- Swing with feet on pressure sensors or barefoot on grass; feel weight move from trail to lead foot.

- Pause at impact for a fraction to self-check force distribution (lead foot loaded).

H2: Case study snapshot (example athlete)

Player A – amateur golfer, 85 mph driver clubhead speed, inconsistent ball striking.

- Assessment: Motion capture showed early arm dominance; force-plate data revealed insufficient lead-foot GRF at impact.

- Intervention: Pelvic-lead and single-leg strength work; rotational medicine-ball drills; launch monitor sessions for feedback.

- Outcome after 8 weeks: Clubhead speed +5 mph, smash factor improved by 0.08, more consistent strike pattern and better dispersion.

H2: Benefits and practical tips for coaches and players

- Benefit: Objective biomechanics shortens the feedback loop-fix the real cause instead of symptoms.

- Tip: Prioritize sequence over raw power-improving timing often yields bigger gains than just hitting harder.

- Tip: use consistent measurement tech (same launch monitor, same camera angles) to track real progress.

- Tip: Train the body and the movement-ignore one and improvements will be limited.

H2: SEO-focused content checklist for this topic

- Include primary keywords on the page title, H1, and within first 100 words: “modern golf swing”, “biomechanics”, “golf swing analysis”.

- Use related keywords throughout: “clubhead speed”, ”kinematic sequence”, “launch monitor”, “ground reaction forces”, “swing tempo”.

- Provide structured content (H2/H3 headings, bullet lists, tables) for readability and search engines.

- Use images with descriptive alt text (e.g., “golf swing kinematic sequence diagram”) and captioned figures for enhanced SEO.

H2: Speedy reference – drills & metrics table

| Drill | Primary focus | Target metric |

|---|---|---|

| Pelvic-lead step | Sequencing | Pelvis peak velocity timing |

| Med ball throws | Rotational power | Clubhead speed |

| Single-leg squats | GRF & balance | Stability at impact |

For players and coaches seeking measurable improvement, focusing on biomechanical principles-kinematic sequence, effective use of ground reaction forces, and coordinated timing-offers the most reliable path to more distance, better ball striking, and greater consistency in the modern golf swing.