Beginning golfers frequently display a set of recurring technical faults that do more than reduce immediate scoring – they hinder efficient motor learning and elevate the chance of overuse injuries. Here, “common” is used in its standard sense (frequently observed or typical) to describe repeated errors that show up across novice populations. These predictable problems – involving grip, stance, alignment, posture, swing path, tempo, ball position, and short‑game technique – have observable impacts on shot outcome, practice productivity, and player confidence.This piece distils findings from sports‑biomechanics research, applied motor‑learning work, and coaching trials to recommend empirically informed corrections for each error category. Where available the synthesis privileges randomized trials, biomechanical modelling, and controlled coaching studies, and it examines mechanisms by which specific faults degrade performance, the relative effectiveness of corrective approaches (cueing, constraint‑led tasks, purposeful variability, augmented feedback), and practical prescriptions coaches and learners can apply. The intent is practical: convert scientific evidence into clear, testable interventions that promote robust skill acquisition and on‑course transfer.

Grip Foundations: Mechanics, Assessment, and Practical Fixes

The grip is the primary mechanical interface between player and club: it sets clubface orientation, transmits forces through the kinematic chain, and coordinates forearm and wrist rotations during the swing. A functional grip distributes pressure across the base pads of the fingers and the heel of the hand rather than concentrating load on the fingertips or the ulnar edge of the palm. That balance encourages a neutral wrist at address and a controlled release through impact. Mechanically, the grip must permit measured pronation/supination of the lead forearm while the trail wrist retains a mild radial deviation during the backswing to stabilise face angle. Too much pressure,uneven pad contact,or extreme forearm rotation increases torque at the wrist/elbow,undermines face control,and raises the risk of tendon or joint overload.

good evaluation combines simple observational checks with instrumented measures to capture how the hands behave statically and dynamically. Recommended assessment tools include:

- Visual checklist for grip style (overlap, interlock, ten‑finger), the V shapes formed by thumb/index finger, and palm/clubface contact at address;

- High‑speed video (face‑on and down‑the‑line) to document wrist set, early release, and forearm rotation timing;

- Grip‑pressure sensors or pressure‑mapping grips

- Digital goniometry to quantify static wrist angles against normative ranges.

to reveal excessive or asymmetric loading; and

Using these methods together produces both coachable visual cues and numeric baselines to measure change.

Corrective work should follow motor‑control and tissue‑loading principles: begin with low‑complexity tasks,progress to varied contexts,and apply timely feedback to speed learning. Evidence‑backed practices include:

- Gradual grip‑pressure training – use biofeedback or sensors to train a moderate feel (for many players a perceived 3-5/10) and break the tendency to “squeeze”;

- External focus cues (such as, “sense the clubhead accelerate into the ball”) rather than internal joint instructions to encourage automatic control;

- Targeted drills such as a towel‑under‑arm connection drill, hinge‑hold routines to establish wrist set, and slow‑motion swings emphasizing the timing of lead‑forearm rotation;

- Temporary tactile aids (thin grip tape or slightly larger grips) to redistribute pressure while preserving touch.

Interventions must be tailored: a correction that fixes one player’s early release can be counterproductive for another with limited wrist extension.

Practical coaching notes: spend 5-10 minutes per session on grip neuromuscular drills, move to variable practice (different clubs and targets) once pressure and wrist alignment are reliable, and retest every 2-4 weeks with the same measures. Use small, measurable goals (such as, lower peak grip pressure during a 10‑shot block while maintaining dispersion) to support retention. Follow graded exposure principles when pain is present and refer to medical professionals if tendon load pain continues beyond four weeks.

| Common Fault | Biomechanical impact | Quick Fix Cue |

|---|---|---|

| Grip too tight | Limited wrist hinge; early release | “Hold, don’t squeeze – aim 3/10” |

| Ulnar‑side pressure | Closed or unpredictable face at impact | “Roll the V slightly toward the lead shoulder” |

| Excessive forearm supination | Hook tendency; elbow stress | “Feel the lead forearm rotate under on the downswing” |

Stance & Balance: Evidence‑Informed Set‑Up and Weight Transfer

The geometry of the base creates the constraints for a repeatable swing. Research and biomechanical models indicate that a moderately wider stance increases lateral stability but can limit axial rotation; a very narrow stance gives rotational freedom but sacrifices balance. Coaches should choose a stance that is club‑ and shot‑specific (wider for longer clubs or shots demanding a low, stable trajectory; slightly narrower for short, more rotational shots) and that respects the player’s natural hip‑width. Foot‑flare (commonly 10-20° on the lead foot, slightly less on the trail foot) can reduce compensatory ankle torque and support consistent pelvic rotation.

Managing weight through the swing improves strike quality and reduces compensations. Force‑plate and kinematic studies typically show a backswing weight bias onto the trail foot followed by a controlled downswing shift toward the lead foot at impact; ideal transfers are quick yet controlled to avoid early lateral sway. Supported coaching cues include maintain knee flexion, keep weight on the midfoot to ball of the foot, and start the downswing with lower‑body sequencing. Useful practice prompts to embed these principles:

- Feel pressure into the trail side during the backswing (but not excessive heel loading)

- Sense forward shift through impact (a weight transfer, not a lateral slide)

- Preserve spine angle to maintain a consistent COM pathway

Stability training lowers injury risk and helps weight transfer consistency. A short micro‑program focused on proprioception, single‑leg balance, and anti‑rotation strength produces measurable improvements in stance control and swing kinetics. The table below lists short, evidence‑aligned exercises that fit into warm‑ups or off‑course conditioning routines.

| Exercise | Focus | Dosage |

|---|---|---|

| single‑leg balance | Proprioception | 3×30s each leg |

| Pallof press | Anti‑rotation | 3×8-12 each side |

| Half‑kneeling chops | Sequencing & core | 3×6-8 each side |

Translate stability improvements into on‑course gains using repeatable measures during practice: video of address‑to‑impact kinematics, impact‑tape patterns or launch‑monitor dispersion, and simple single‑leg hold tests provide objective benchmarks. Progressively increase proprioceptive challenge and reassess with the same tests; gains should align with tighter dispersion, steadier launch conditions, and fewer compensatory movements. For quicker learning, combine short, focused drills (for example, step‑through or pause‑at‑top) with immediate objective feedback to consolidate reliable weight transfer mechanics.

Aiming & visual Calibration: Practical Drills to Improve Directional Control

Accurate visual calibration underpins consistent directional control. Players who routinely misalign feet, hips, or the clubface introduce systematic lateral bias into their dispersion. Motor‑control work shows that focusing externally on a clear target line reduces variability more effectively than internal technical instructions. In practice,prioritise locking a concrete reference (an alignment stick,a spot on the fairway,or a specific flag) rather than abstract “aiming” concepts. While equipment debates are common, they can distract from the perceptual‑motor step that should precede fit or gear choices. Early instruction should re‑centre on a repeatable pre‑shot visual routine that fixes the target line before motion begins.

Drills that improve perceptual accuracy and map directly to on‑course outcomes include:

- Gate drill: position two clubs slightly wider than the head and swing through them to encourage a square path;

- Towel‑line address: lay a towel on the intended line to calibrate foot and shoulder alignment;

- Mirror or camera checks: static setup checks from face‑on and down‑the‑line views to confirm shoulder and face alignment;

- Two‑ball alignment: place a second ball on the intended target line and hit finite‑distance targets to refine aim.

Each drill couples an external visual cue with constrained practice to accelerate visual‑motor mapping and reduce angular error shot‑to‑shot.

| Drill | Primary Goal | suggested Volume |

|---|---|---|

| Gate drill | Square clubface through impact | 3×10 swings |

| Towel‑line address | Repeatable feet/shoulder alignment | 5×5 setups |

| Two‑ball alignment | Short/medium range targeting | 4×6 shots per distance |

Begin with blocked repetitions to build the visual‑motor mapping, then move to randomized targets to challenge transfer and resilience under variability.

Objective feedback speeds retention: measure lateral dispersion relative to a marked line, review down‑the‑line video, or use alignment‑stick markers to quantify advancement. Encourage self‑assessment metrics (mean lateral error, consistency band) and change drills when variability plateaus. As a rule of thumb, aim to reduce lateral standard deviation by steady increments before altering other technical elements so that later changes are not confounded by persistent aiming errors.

Posture & Spinal Mechanics: Set‑Up, Load Management, and Injury Prevention

A biomechanically efficient address and maintained posture through the swing lower injurious tissue loads and increase consistency. Adopt a controlled hip hinge with a neutral lumbar spine,modest knee flexion,and the head balanced over the stance centre. These set‑up features distribute compressive and shear forces across larger joint surfaces, decrease peak loading on lumbar discs and facets, and enable safer force transfer from the ground through the trunk to the club.

Practical posture corrections for beginners should be simple, repeatable, and evidence‑informed. Key actions include:

- Chair‑to‑address drill: hinge from a low chair to learn the hip hinge and neutral spine;

- Stable footwear and base: supportive shoes and a shoulder‑width stance to reduce excessive trunk compensation;

- hand height & shaft tilt: set hands so forearms create a plane that favours neutral wrist alignment at impact;

- Low‑level core brace: teach gentle transverse abdominis activation to protect the lumbar spine during rotation.

Integrate load management into weekly practice to limit cumulative microtrauma. Structure sessions with progressive volume and intensity, include dynamic warm‑ups for thoracic and hip mobility, and alternate high‑repetition technical blocks with low‑impact conditioning.The table below summarises corrections, simple on‑course cues, and an evidence grade to guide clinicians and coaches.

| Correction | On‑course Cue | evidence Level |

|---|---|---|

| Neutral spine at address | “Hinge at the hips; chest over toes” | Moderate |

| Thoracic mobility drills | “Rotate shoulders; keep hips still” | Moderate‑High |

| Progressive practice volume | “Shorter sessions, more variety” | High |

Preventive conditioning complements technical coaching: screen for asymmetries, prioritise posterior‑chain strength, and restore thoracic rotation to reduce compensatory lumbar motion. Encourage early reporting of symptoms and follow graded return‑to‑play steps; persistent pain, neurological signs, or functional limits require physiotherapy or sports‑medicine referral. Combining simple setup cues with structured load management and targeted exercise helps novices lower injury risk while accelerating skill gains.

Swing Path & Face Control: diagnostics, Repatterning, and Progressive Practice

Effective remediation starts with a structured diagnostic routine combining qualitative observation and quantitative data. Use a coached movement inventory (face‑on and down‑the‑line video, high‑speed impact clips) alongside instrumented metrics (launch monitor outputs: club path, face angle, attack angle) and on‑club tests (impact tape, face stamps). This mixed‑method approach mirrors clinical practice - combining player reports, practitioner observation, and objective device data – to create a reliable baseline for targeted interventions. Maintaining repeatable test conditions is essential to distinguish transient coordination lapses from persistent technical faults.

Repatterning should follow motor‑learning steps: constrain degrees of freedom, provide clear external cues, then gradually restore speed and task variability. Useful tactics include:

- Constraint modification: change grip, stance, or use implements (alignment rods, headcovers) to bias the desired path and face position;

- External attentional focus: emphasise ball flight or a target rather than internal joint positions to speed acquisition;

- Segmental isolation: short‑swing and half‑swing drills that separate forearm/wrist action from torso rotation.

These methods accelerate neural repatterning and reduce compensations commonly seen in novices.

Progressive drills move repatterned movements into robust skills by sequencing from constrained practice to contextually rich scenarios. A compact progression is shown in the table below:

| Drill | Primary Target | progression Criterion |

|---|---|---|

| Gate drill (two tees) | Club path control | 10 consecutive passes without contacting tees |

| Tee‑on‑face drill (tee attached to face) | Face orientation at impact | Consistent marks toward the target line |

| Impact‑bag strikes | Compression & square face | Repeatable rebound and consistent sound |

start drills at reduced speed, increase tempo only after progression criteria are met, then blend into full‑swing work and on‑course simulations to ensure transfer.

Feedback and monitoring complete the learning cycle: deliver immediate, salient feedback (impact marks, video playback, launch‑monitor figures) to correct errors and use delayed summary feedback to promote retention. Track objective metrics – mean lateral dispersion, average face angle at impact, percentage of shots within a target corridor – and set time‑bound, measurable goals (for example, reduce mean face‑open angle by a set incremental target over several weeks). Use an iterative reassessment plan: baseline → 2‑week formative check → 6‑week retention test, adjusting constraints and drill dosage based on measured progress. Evidence‑based progression coupled with objective monitoring is central to converting short‑term fixes into lasting skill change.

Tempo, Rhythm & Sequence: Training Methods to Stabilise Timing

Modern motor‑control perspectives view tempo and rhythm as outcomes of coordinated neuromuscular sequencing rather than isolated items to memorize. Reliable performance emerges when players internalise a consistent proximo‑distal order (hips → torso → arms → club) and preserve the timing relationships between segments. From an information‑processing standpoint, stabilising intersegmental delays reduces variability in face orientation and clubhead speed at impact, improving repeatability under different task demands.

Timing drills should balance fidelity (task resemblance) and controlled variability to foster robust motor solutions. Supported approaches include metronome‑paced rehearsal, differential practice with subtle perturbations, and contextual‑interference schedules that mix shot types. Practical protocols include:

- Metronome practice: 3×60 swings using a backswing:downswing ratio (for example, 3:1);

- Variable practice: change target distance or lie every 6-8 swings to promote adaptability;

- Blocked → Random progression: start with blocks to embed sequence, then progress to random ordering for retention.

Integrate objective feedback to amplify learning: intermittent knowledge of performance (KP) such as slow‑motion sequencing video and knowledge of results (KR) such as tempo ratios or carry dispersion help players adjust. The table below summarises short micro‑protocols suitable for a single 20-30 minute practice slot.

| Drill | Target | Duration |

|---|---|---|

| Metronome tempo | 3:1 backswing:downswing | 8-12 min |

| Variable aim | Three distances in random order | 6-10 min |

| Sequence check | Slow‑motion video review | 4-6 min |

Implement these methods with periodisation and measurable progression: begin with high‑frequency, low‑context variability to establish timing, then increase contextual demands and reduce augmented feedback to encourage retention and transfer. Use retention and transfer tests (no external cues, simulated pressure) to confirm consolidation. Coaches should nurture self‑regulation – players who monitor tempo errors and progressively adjust task difficulty develop more stable rhythm and sequencing than those relying solely on coach direction.

Short‑Game Mechanics & Green Management: Reliable Contact, Distance, and Strategy

Novices – players with limited on‑course experience and variable motor patterns – benefit most from a mechanics‑first approach that prioritises reproducibility over power. Anchor short‑game coaching on three repeatable elements: stance and weight distribution, low‑hand control, and consistent strike position.Early correction of common short‑game faults reduces overall variability; frequently seen issues include:

- Overactive wrists at impact producing thin or fat contacts;

- Ball‑position inconsistency between chip and pitch setups;

- Poor weight transfer causing inconsistent distance control.

Address these with low‑complexity isolation drills (for example narrow‑stance chips to foster low‑hand control) and immediate objective feedback such as impact tape or entry‑level launch monitoring.

Green management for newer players should emphasise pace control and conservative target selection to cut three‑putt risk and raise up‑and‑down rates. Prioritise pace over exact line on longer returns and choose bail‑out landing areas for chips/pitches (aim for a larger flat zone rather than a tucked pin). A compact practice plan that links skill and decision making is shown below:

| Drill | Primary Focus | Duration |

|---|---|---|

| 3‑Spot putting | Pace control | 10 min |

| Up‑and‑down circuit | Distance + target selection | 15 min |

| Pitch ladder | Trajectory & landing spot | 10 min |

This structure supports measurable improvements in putting and short‑game decisions.

design practice sessions for beginners around motor‑learning principles: distributed practice,purposeful variability,and scheduled augmented feedback.A balanced session template might be:

- Warm‑up (10 min) – dynamic mobility and short putts to calibrate feel;

- Skill block (20-30 min) – focused chipping/pitching drills with a single performance metric (such as landing‑zone accuracy);

- contextual play (15-20 min) – simulate on‑course sequences that combine a tee shot, chip/pitch, and two putts.

Interleaving shot types and using intermittent feedback (video or concise coach cues) improves retention and transfer more than purely blocked repetition.

Progression should be modest and quantifiable: set short‑term targets (such as increase up‑and‑down percentage by a set amount across four weeks) and track straightforward metrics like putts per hole, proximity for chips, and clean‑strike rate. Keep a problem‑solving focus – prioritise high‑leverage changes (stance and contact) before stylistic adjustments – and maintain concise, reproducible cues to speed beginner development.

Q&A

Below is an academic‑style Q&A adapted for the article “Common Novice Golf Mistakes: Evidence‑Based Remedies.” Each response summarises the typical error, the biomechanical or motor rationale, the current evidence type and strength, practical corrective methods and drills, objective markers for progress, and safety notes.

1) Q: What defines a “common novice golf mistake” from an evidence perspective?

A: A common novice mistake is a recurrent technical or tactical error that reliably harms shot consistency, distance, accuracy, or increases injury risk and that can be modified through instruction or practice. Identification draws on coach observational audits, biomechanical analyses (motion capture, force plates), and some intervention work.evidence strength varies: diagnostic descriptions have strong face validity and consistent coach agreement; lab biomechanical explanations are well supported, but high‑quality RCTs testing specific fixes remain relatively limited.

2) Q: What grip errors do beginners typically make and what does the evidence recommend?

A: Typical problems include a grip that is too weak or too strong, inconsistent pressure, or incorrect hand placement producing face misalignment at impact. Coaching observations and biomechanical studies link these factors to face orientation and ball flight; experimental work shows hand placement changes can alter face angle. Remedies include teaching neutral V alignment (thumb/index finger pointing toward the trail shoulder for right‑handers),settling perceived grip pressure in a moderate range (often 3-6/10),mirror or video checks of V position,towel‑under‑arm connection drills,and half‑swings focused on consistent pressure with sensor or subjective scales. Progress markers: stable face angle at impact and reduced dispersion. Safety: avoid over‑gripping to limit forearm tension and tendon overload.

3) Q: How do novice stance faults present and how should they be corrected?

A: Frequent stance faults are feet too narrow or too wide, knees locked or over‑bent, and weight held on toes or heels. Biomechanics show stance width affects balance, hip rotation, and force transfer. Corrective guidelines: adjust stance relative to the club (narrower for wedges, wider for long clubs), modest knee flex, weight on midfoot, and a roughly 55/45 weight bias at address for many irons. drills: place an alignment stick between heels to standardise width, single‑leg balance work, and a step‑in drill to feel correct width. Progress markers: improved balance measures, reduced lateral sway, and more consistent contact. safety: make stance changes gradually; avoid extremes that load knees or low back.

4) Q: What alignment errors are common and how can novices fix them?

A: Common issues are an open or closed stance related to the target line, bodies aimed differently from the clubface, and visual misperception of the target line. Evidence from vision and coaching studies shows misalignment is a major cause of directional error; using alignment aids in practice reduces errors in controlled settings. Methods: aim the clubface first, then align feet, hips, and shoulders parallel to that line; use an intermediate visual reference (a spot 10-15 ft ahead) to sharpen aim. Drills: gate work with alignment sticks, mirror checks, and an “aim twice” pre‑shot routine. progress markers: smaller directional bias and quicker consistent setup. Safety: avoid overthinking alignment to the point of tension.5) Q: How does poor posture affect play and what evidence‑based corrections exist?

A: Faults include slumped or overly upright posture, rounded shoulders, and insufficient hip hinge.biomechanical evidence supports that a neutral spine and proper hip hinge promote torso rotation and consistent low‑point location; poor posture increases variability and injury risk. Corrections: adopt a neutral spine with hip hinge, slight knee flex, and chest over the ball; drills include wall‑hinge practice, using an alignment stick along the spine at setup, and posture holds to build muscular endurance. Progress markers: stable spine angle in swing videos and consistent low‑point location. Safety: for players with low‑back pain begin supervised mobility and core work before high‑volume rotation.6) Q: What swing path problems do novices show and how are they corrected?

A: Typical path errors are exaggerated outside‑in (slice) or inside‑out (hook) patterns and plane issues such as too steep or too flat takeaways.Motion analyses link path to ball curvature; interventions using visual feedback, alignment aids, and motor‑learning strategies reduce pathological paths. Diagnostics: interpret ball flight, use impact tape, or a launch monitor to quantify path and face angle. Corrections: for outside‑in encourage a shallower takeaway and an inside feel; for inside‑out moderate excessive in‑to‑out by calming upper‑body transition; drills include swing path gates, connection drills (towel under armpit), pause‑at‑top rehearsals, and face‑on video review. Progress markers: improved path angle numbers, reduced shot curvature, and more centre‑face contact. Safety: progress tempo and speed gradually to avoid strain.7) Q: How should novices train tempo and what does the evidence show?

A: typical tempo problems are swings that are too quick/aggressive or excessively tentative, causing timing breakdowns. Motor‑control literature indicates that consistent tempo increases timing and reproducibility; metronome and rhythm training are effective in related domains and show promise in golf coaching. Approaches: adopt a reproducible tempo ratio (many coaches use 3:1 backswing:downswing), reinforce a routine, and practise with metronome cues, slow‑motion tempo ladders, and half‑speed sequenced swings. Progress markers: consistent transition dwell, steady swing times, and reduced dispersion. Safety: avoid sudden increases in speed after prolonged slow practice; build intensity gradually.

8) Q: How does wrong ball position affect shots and what placement rules work?

A: Errors include the ball too far back (fat shots) or too far forward (thin/topped strikes) and inconsistent placement across clubs. kinematic analyses and coach consensus show ball position affects low‑point, loft delivered, and launch angle. Guideline: short irons slightly inside front heel, mid‑irons near centre, long irons/woods more forward (driver inside lead heel), with individual adjustments as needed. Drills: use an alignment stick or coin as a repeatable marker, tee/marker practice, and low‑point drills (e.g., towel just behind a wedge ball). Progress markers: consistent divot pattern and improved launch metrics. Safety: avoid overcorrecting with forceful swings; use modest volume and feedback.

9) Q: What are common short‑game faults and evidence‑supported remedies?

A: Typical short‑game issues are poor setup (weight, grip), wrong club choice, inconsistent contact, and distance control problems. Short‑game performance heavily influences scoring, and studies indicate variable practice with targeted feedback improves proximity and consistency. Remedies: for chips/pitches adopt a narrow stance, ball back of centre for chips, a descending strike and acceleration through the contact; bunker work should include open stance, slightly forward weight, and acceleration through sand; putting focuses on a stable lower body, consistent setup, and distance control drills. Progress markers: improved proximity, fewer three‑putts, and better strokes‑gained metrics.Safety: avoid repetitive heavy sand strikes without technique instruction to protect wrists and shoulders.

10) Q: How should an evidence‑based corrective program for novices be organised?

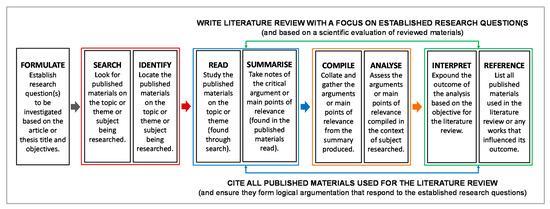

A: Structure:

– Assessment: baseline video, mobility and balance screens, and shot data to identify top errors.- Prioritisation: focus on 1-2 high‑impact faults to minimise cognitive load.

– Motor‑learning approach: begin blocked practice for acquisition, then move to variable and contextual practice for transfer; use faded feedback (many cues early, fewer later).

– Progressive overload: start with low volume at controlled speed, increasing reps and speed as consistency improves.

– Interdisciplinary input: add mobility, strength, and conditioning where deficits underpin technical problems.

safety: include dynamic warm‑ups, limit full‑speed reps early, monitor pain and fatigue, and adapt for pre‑existing issues.

11) Q: Which objective tools help measure progress?

A: Useful instruments include face‑on and down‑the‑line video for kinematic review; launch monitors for ball speed, launch, spin, carry, and dispersion; pressure plates or force sensors for weight‑transfer analysis when available; and simple field tests like divot patterns and proximity charts. Evidence shows objective feedback speeds learning when paired appropriately with coaching cues.

12) Q: What are the main limits of the evidence and how should practitioners interpret guidance?

A: Limitations: few high‑quality RCTs test individual techniques, much guidance is drawn from biomechanical theory, cohort/observational studies, and motor‑learning principles, and participant heterogeneity (anatomy, prior motor patterns) complicates one‑size‑fits‑all prescriptions.Interpretation: use evidence as a framework rather than rigid rules – combine objective assessment with individualised coaching and iterative outcome monitoring.

13) Q: What safety priorities should coaches stress when implementing corrections?

A: priorities include a dynamic warm‑up for hips, thoracic spine, shoulders, and wrists; gradual progression with limited high‑speed exposure when introducing new mechanics; stop or modify work if sharp or persistent pain occurs and refer when needed; address mobility and strength deficits (core, hips, shoulders) to lower compensatory patterns; ensure equipment is appropriately sized and weighted to reduce unnecessary compensation. Sports‑medicine literature supports that warm‑ups, graded load exposure, and targeted conditioning lower overuse risk.

14) Q: What concise teaching cues work well with novices?

A: Practical short cues include:

– Grip: “V’s toward the trail shoulder; light enough to hold, firm enough to control.”

– Posture: “Hinge at the hips; chest over the balls of your feet.”

– Stance/Alignment: “Set the clubface, then aim your body.”

– Swing path: “Feel the club drop inside on the downswing” (for slices) or “Let your hands lead the head” (for hooks).

– Tempo: “One‑two‑three (backswing), four (downswing)” or use a metronome ratio.

– Ball position: “Short clubs near centre,long clubs forward.”

Treat these as starting heuristics and adapt to individual needs.

15) Q: Where can coaches and players pursue higher‑quality evidence and further education?

A: Look to peer‑reviewed journals in sports biomechanics, sports medicine, and motor learning; professional coaching organisations (PGA/LPGA education modules) that translate research into coaching practice; and university or lab publications on swing mechanics, ground reaction forces, and injury epidemiology. Collaboration with biomechanics labs or certified swing analysts can provide advanced assessment when warranted.

Concluding note

The corrective principles presented rest on biomechanical reasoning,motor‑learning theory,and coaching consensus. Practitioners should follow a clear assessment → prioritised intervention → progressive practice pathway, incorporate objective feedback where possible, and keep safety front‑of‑mind with warm‑ups, load management, and sensible progression. For novices,limited,focused adjustments combined with quality repetitions and consistent feedback produce better transfer and lower injury risk than attempting multiple simultaneous changes.

If desired,each section here can be expanded with specific drill scripts,coachable cue sets,and sample four‑week practice plans tailored to an individual learner profile.

recurring technical and tactical deficiencies – grip, stance, alignment, posture, swing path, tempo, ball position, and short‑game execution – commonly constrain novice golfers’ performance and increase injury exposure. across these areas the literature supports a compact set of corrective principles: establish repeatable hand placement and moderate grip pressure; adopt a stance and posture that balance stability with rotational freedom; confirm alignment using external references; develop an on‑plane swing while minimising excessive lateral forces; stabilise tempo with rhythmic cues or metronome work; use simple ball‑position rules tied to club choice; and prioritise contact quality in chipping, pitching, and putting through graded, progressive drills. Safety measures – thorough warm‑ups, gradual loading, attention to musculoskeletal limitations, and avoiding forceful compensatory movements – should accompany all technical change.

for coaches and learners, the evidence favours structured, feedback‑rich practice: short focused sessions that emphasise deliberate practice, variable and contextual drills, routine objective feedback (video, kinematic or pressure measures, and coach input), and periodic reassessment to confirm on‑course transfer. Training aids can accelerate awareness of specific faults but are adjuncts to guided motor learning, not substitutes for individualised coaching. Given heterogeneity across players and relatively few long‑term trials, individualisation remains essential. Integrate technique changes with the learner’s physical capacity,goals,and injury history,and favour conservative progression where tissue tolerance is uncertain. Future research should harmonise outcome metrics, evaluate long‑term retention and transfer, and study interactions between conditioning and technical change.

Ultimately, applying an evidence‑based, learner‑centred approach – clear, testable corrections, systematic practice, and attention to safety - gives novices the best chance to reduce common errors, raise performance, and sustain enjoyment and participation in golf.

Fix your Game Fast: Evidence-Based Fixes for 8 common Beginner golf Mistakes

Tone: Authoritative

Why evidence-based fixes matter for beginner golfers

beginners frequently enough patch problems with speedy tweaks that can create new faults. An evidence-based approach-using biomechanics, motor learning principles (deliberate practice, variability, external focus), and targeted drills-delivers faster, more reliable improvement. below are eight common beginner golf mistakes with clear causes, research-aligned fixes, practical drills, and realistic practice timelines.

Table: Quick overview of 8 beginner mistakes and fixes

| Mistake | Common cause | quick evidence-based fix |

|---|---|---|

| Slicing | Open clubface & out-to-in swing path | Neutral grip + inside takeaway drill |

| Hooking | Closed face & inside-to-out path with overrotation | Weaker grip + controlled release drill |

| Thin/Top Shots | Early extension / poor posture | Posture check + chair drill |

| Fat Shots | Reverse pivot / early weight shift | Balance drill + slow tempo swings |

| Poor Short Game | Wrong setup & hand action | Landing spot practice & bump-and-run |

| 3-putting | Poor green reading & inconsistent speed control | Speed drills + aiming routine |

| Alignment errors | Visual aiming bias | Club on ground alignment routine |

| Inconsistent tempo | Nervous speed & muscle tension | Metronome tempo practice |

1. Slice: diagnose and stop the cut

Symptoms and root causes

- Ball curves dramatically left-to-right (for a right-handed golfer).

- Common causes: weak/neutral-to-weak grip,open clubface at impact,out-to-in swing path,insufficient torso rotation.

Evidence-based fixes

- Grip adjustment: rotate hands slightly to create a neutral/stronger grip so two knuckles appear on the left hand (RHBH). A neutral-to-strong grip helps square the clubface at impact.

- Path correction (inside takeaway): Practice taking the club back slightly inside the target line to encourage an in-to-out path. Research in motor learning supports simple external-focus cues (e.g., “swing toward the fencepost”) over complex internal mechanics.

- Clubface awareness: Use alignment sticks or a face-marking spray to see where the face points at impact.

Drills

- Two-towel drill: place a towel just outside the ball and practice swings missing the towel to promote inside takeaway.

- Gate drill with two tees to train a square-to-closed face through impact.

- Video feedback: use slow-motion recordings to check face angle and path (external-focus cue: “swing to the right of target on takeaway”).

2. Hook: fix the overdraw

Symptoms and causes

- Ball curves sharply right-to-left (for RHBH).

- Caused by an overly strong grip, early-to-late release (excessive supination), or too inside-out path combined with closed face.

Evidence-based fixes

- Weaken the grip slightly: rotate both hands a bit left on the handle to reduce excessive forearm rotation.

- Delay release: practice keeping the clubface neutral longer into the downswing using impact bag drills.

Drills

- Impact bag drill: hit a soft bag to feel a square clubface at contact and discourage overrelease.

- Alignment stick placed just outside the ball to encourage a shallower path and reduce overrotation.

3. Thin or topped shots: fix contact

Symptoms and causes

- Ball struck thin or topped; low flight and low distance.

- Frequently enough caused by early extension (standing up during the swing), poor posture, or lifting the head.

Evidence-based fixes

- Posture and spine angle: set up with a slight knee flex and hinge from the hips keeping the spine angle stable through impact.

- Weight distribution: keep pressure on the lead leg at impact; use slow-motion practice to feel forward weight.

Drills

- Chair drill: place a chair just behind your hips at address and swing without touching it-this promotes proper hip hinge and prevents early extension.

- Divot drill: practice hitting short wedge shots and examine divots to ensure downward strike (ball then turf).

4.Fat shots and poor turf contact

Symptoms and causes

- Heavy shots that hit the ground before the ball, resulting in lost distance and poor spin.

- Caused by reverse pivot, sway, early weight shift to front foot, or poor sequencing.

Evidence-based fixes

- Balance and sequencing: maintain center of mass over feet; train sequential rotation from hips to torso to arms.

- Tempo control: slow, controlled downswing reduces early lateral movement.

Drills

- Feet-together drill to force balance and better sequencing.

- Slow-motion half swings to practice weight shift timing-finish on lead leg.

5. Poor short game: chipping and pitching errors

Symptoms and causes

- Inconsistent distance control, excessive spin, thin chips or skulled shots.

- Caused by wrong club selection, poor setup (hands position), too much wrist action.

Evidence-based fixes

- Set up correctly: hands slightly ahead of the ball, weight favoring lead foot, narrow stance for chipping.

- Simplify motion: use a three-quarter shoulder turn and minimal wrist hinge for predictable contact.

- Target-focused practice: practice to specific landing spots to improve distance control-motor learning studies favor goal-directed practice.

Drills

- Landing-spot drill: pick a landing spot and vary club to see roll differences.

- Bump-and-run practice using lower-lofted clubs to learn roll-out behavior.

6.Putting problems: speed and alignment

Symptoms and causes

- three-putts, missed short putts, inconsistent speed.

- Caused by poor distance control, misread greens, inconsistent setup and stroke.

Evidence-based fixes

- Speed first: prioritize distance control-research shows that putting within the hole is more likely with correct speed even when aim is slightly off.

- Pre-putt routine: establish aim, test speed with practice strokes, pick a specific line and commit.

- External focus cue: aim to “roll ball over a spot 3” (a mark on the green) rather then focusing on arm mechanics.

Drills

- Gate drill for face alignment and stroke path.

- Three-circle drill (make putts from progressively farther rings) to build confidence from 3-6-9 feet.

- Speed ladder: putt to targets at fixed distances to train pace control.

7. Alignment and aiming errors

Symptoms and causes

- Consistent misses to left or right from setup errors.

- Visual bias, inconsistent pre-shot routine, or poor use of alignment aids.

Evidence-based fixes

- Routine and reference lines: place an alignment stick or club along target line at address and use it every time until muscle memory forms.

- Two-point check: pick a distant target and a spot 2-3 feet in front of the ball on the intended line-this locks in aim.

Drills

- Mirror or club-on-ground routine to check shoulder/feet alignment.

- Randomized aiming drills: hit to different targets to prevent rote alignment errors and build adaptability.

8. Inconsistent tempo and nervous swings

Symptoms and causes

- Rushed or jerky swings, loss of distance, errant contact-worse under pressure.

- Caused by tension,poor pre-shot routine,lack of rhythm.

Evidence-based fixes

- metronome training: practice swings with a metronome to stabilize backswing-to-downswing rhythm. Studies show tempo training improves consistency.

- Pre-shot routine and breathing: a short routine with deep breaths reduces tension and promotes consistent tempo.

- External focus and imagery: think target or ball flight, not body parts-external focus enhances automatic control per motor control research (Wulf).

Drills

- Metronome or music tempo drill (e.g., backswing on beat 1-2, downswing beat 3).

- Pressure practice: simulate nervous conditions (countdown, small penalty) to learn to maintain tempo under stress.

Practice structure and motor-learning tips (evidence-based)

- Deliberate practice: aim for focused sessions with specific goals (30-60 minutes targeting one skill), immediate feedback, and incremental difficulty.

- Variable practice beats pure repetition: alternate clubs, targets, and lies to build adaptable skill rather than perfecting a single movement pattern.

- Random vs blocked practice: blocked practice (repeating same shot) improves performance during practice but random practice (mixed shots) improves retention and transfer-use both intelligently.

- External focus cues: phrases like “send it to the flag” are more effective than “rotate your hips” for performance and learning.

- Feedback: immediate video or coach feedback is powerful. Use launch monitors for objective metrics (ball speed, spin, launch angle) when available.

Sample 4-week practice plan

- Week 1: Fundamentals-grip, stance, posture (30-45 min on range; short game 15-20 min).

- Week 2: Path and clubface-drills for slice/hook (use alignment sticks & impact bag) + tempo training.

- Week 3: Short game focus-landing spot practice, bump-and-run, chips from different lies.

- Week 4: Integration & pressure-play 6-9 holes practicing routine and course management; simulate pressure on range.

Practical tips to speed improvement

- Track outcomes, not just mechanics: keep a short practice log (miss direction, contact, club used).

- Use simple, repeatable routines on every shot to reduce decision noise.

- Limit instruction overload-one technical cue per session improves retention.

- Get periodic coaching checks-every 4-6 weeks-to ensure changes are effective and not compensating faults.

Mini case study: rapid slice-cure in 6 sessions

A recreational right-handed golfer habitually sliced drives. Coach used a three-step plan: neutralize grip, inside takeaway drill, and gate/face spray feedback. After six focused sessions (20-30 minute drills + range practice), the player reduced slice curvature by >50% and gained 10-15 yards due to improved contact. This reflects how targeted, evidence-based interventions produce measurable gains quickly.

SEO-kind FAQ (quick answers for search snippets)

How do beginners stop slicing the ball?

Fix the grip (a slightly stronger grip), learn an inside takeaway, and use alignment aids. Combine these with face-awareness drills and video feedback for faster results.

What is the fastest way to improve putting?

Prioritize speed control drills, establish a simple pre-putt routine, and practice short putts (3-6 feet) to build confidence. Use the three-circle drill and speed ladders.

How long does it take to fix common beginner golf mistakes?

small changes (grip, alignment) often show improvement in days to weeks.Complex issues involving sequencing or pressure control may take 4-8 weeks of deliberate practice and reinforcement.

Suggested short headlines for social sharing (pick one)

- Fix Your slice Fast: 8 Research-Backed Fixes

- Beginner Golf: 8 evidence-Based Corrections

- Stop Slicing, Start Scoring – Science-Backed Tips

Internal links & schema suggestions for WordPress

- Use internal links to related posts: ”Beginner golf drills”, “short game practice”, “putting speed control”.

- Add FAQ schema for the FAQ section to improve rich snippets.

- Use H1 for the main headline, H2 for main sections, and H3 for subpoints (as above) to meet on-page SEO best practices.

Sources & further reading

Relevant topics include biomechanics texts, motor learning research (e.g.,Wulf on external focus),and practical coaching literature. For specific measured feedback, consider using a launch monitor or video analysis tool and consult a PGA/coach for individual assessment.