Introduction

Structured practice is widely accepted as a basic driver of skill growth in sport, but the precise ways in which planned golf drills produce measurable gains in technique, shot repeatability, and competitive outcomes are still not fully resolved. Golf uniquely blends precise motor execution, perceptual judgment, and variable competitive contexts, which complicates the transfer from isolated practice to real‑round performance. Coaches regularly prescribe drill sequences to refine swing mechanics, sharpen short‑game touch, and improve course management, yet controlled investigations that parse which drill elements are active ingredients and how strongly they affect play remain limited.

This paper investigates the effects of structured golf drills using a combination of biomechanical measurement, objective performance tracking, and tightly controlled practice interventions. We define structured drills as reproducible, goal-oriented practice tasks that target discrete movement patterns or decision processes and contrast them with loosely organized, ad hoc practice. The study has three primary objectives: (1) assess whether drill-based regimens produce greater gains in technical markers (for example, clubhead path and impact variables), consistency (shot dispersion and within‑shot variability), and performance outcomes (scoring, greens‑in‑regulation) than equivalent-duration unstructured practice; (2) determine which drill design features (attentional focus, imposed variability, feedback mode, and progression strategy) most reliably predict transfer to on‑course play; and (3) evaluate the persistence of observed improvements over follow‑up periods.

To meet these goals we use a mixed-methods framework that integrates randomized intervention arms, pre/post biomechanical profiling, and extended performance monitoring. Quantitative tests estimate effect magnitudes across kinematic and outcome measures, while participant interviews and adherence logs shed light on perceived usefulness and practical barriers. By tying movement‑level change to functional playing outcomes, the research aims to offer evidence‑based prescriptions for coaches and players about efficient, transferable practice structures and to deepen theoretical models of motor learning in golf.

Foundations for structured Golf Drills: Motor learning, Deliberate Practice and Training Transfer

The rationale for using focused drills to accelerate golf skill draws on established motor learning theory. Conventional stage models (cognitive → associative → autonomous) describe the shift from effortful, error‑prone performance to fluent, automatic execution; this trajectory explains why early practice often centers on error detection while later phases prioritize variability to preserve adaptability. Modern perspectives-such as schema theory and the constraints‑led framework-explain how athletes form generalized motor plans and how the interaction of task, environment, and individual constraints shapes viable movement solutions. These ideas support a planned drill sequence that intentionally moves from technique rehearsal toward adaptable performance execution.

Deliberate practice translates theory into practical prescriptions. Defined by precise targets,high‑quality feedback,concentrated repetition,and graduated challenge,deliberate practice differs fundamentally from mere quantity of repetition by centering purposeful enhancement and systematic error correction. In golf, this approach means designing drills that hone specific mechanics while keeping opportunities for controlled variation so that cognitive representations become both stable and flexible. Augmented feedback-video, coach instruction, or performance metrics-should be applied in a structured way and gradually withdrawn to promote internal error monitoring and retention.

Effective on‑course translation depends on understanding transfer of training. Near transfer increases with similarity between practice and performance cues (movement demands, visual facts, decision load), yet excessive resemblance can reduce adaptability. Coaches therefore must balance specificity with deliberate variability to encourage far transfer across unfamiliar course scenarios. Evidence for the contextual interference effect indicates that interleaved or randomized practice may depress immediate scores but often enhances long‑term retention and adaptability-an effect that can be exploited through phased drill scheduling.

Turning these theories into usable drill design principles yields several actionable rules:

- Specificity plus variability – align practice with key performance constraints while varying secondary elements to develop adaptable motor schemas.

- Goal‑directed structure – define measurable sub‑targets (e.g., dispersion radius, tempo index, preferred shot shape) to guide attention and feedback.

- Feedback sequencing – begin with frequent augmented feedback, then taper frequency to encourage self‑monitoring.

- Contextual interference planning – progress practice from blocked to serial to randomized formats across phases.

- Pressure simulation – add time limits and decision constraints to mimic competitive stress.

Practical mapping of theory to drills:

| Concept | Applied principle | Illustrative Drill |

|---|---|---|

| learning stages | Move from repetition to variability | Movement blocks → mixed‑distance wedge circuit |

| deliberate practice | Clear aims + targeted feedback | Shape‑target drill with video playback |

| transfer | Simulate game constraints for generalization | Timed pressure putting challenge with scoring |

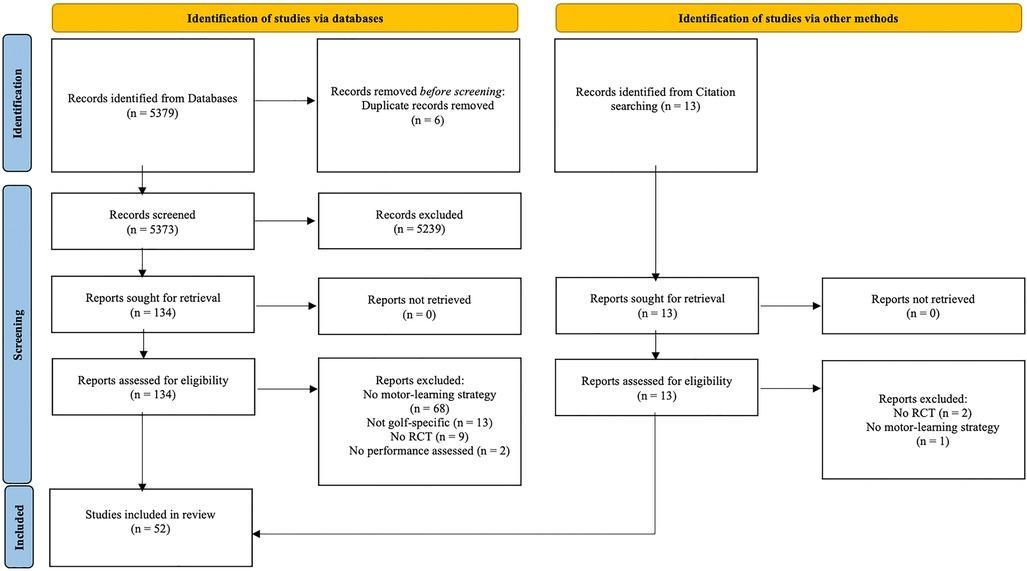

Evaluating Drill Impact: Experimental Designs and Key Metrics

Strong evaluations of drill efficacy require careful experimental choices. Recommended approaches include randomized controlled trials (RCTs) to support causal claims, crossover formats to reduce between‑subject variability, and within‑subject longitudinal tracking to chart individual learning curves. In real‑world settings, single‑case (ABA/ABAB) and quasi‑experimental methods are useful when full randomization is impractical. Each design must be weighed against threats to validity-maturation, carryover, and logistical constraints such as athlete availability and competition schedules.

Outcomes should span technical, tactical, and transfer domains to demonstrate meaningful skill change.Core recommended indicators are:

- Ball‑flight metrics: carry distance, group dispersion, launch angle and spin from launch monitors.

- Biomechanics: clubhead speed, swing tempo, and kinematic consistency via IMUs or high‑speed video.

- performance: strokes‑gained, proximity to hole, and accuracy under simulated pressure.

- Retention and transfer: delayed follow‑up performance and on‑course request.

- Perceptual/subjective: coach ratings, player confidence, and perceived effort.

Measurement validity depends on calibrated instruments and consistent protocols. Use validated launch monitors and synchronized motion capture or inertial systems; document sampling rates and inter‑device agreement.Control environmental variables (wind, turf, ball model) and standardize drill dosage (repetitions, rest). Establish baseline stability with multiple pretests to estimate a minimal detectable change (MDC) so that observed gains exceed measurement noise.

Analytic choices should reflect repeated measures and individual variation.Use linear mixed‑effects models or repeated‑measures ANOVA for group inferences and complement with single‑case analyses to capture individual response patterns. Report effect sizes (Cohen’s d or partial eta‑squared),95% confidence intervals,and consider equivalence or non‑inferiority testing where relevant. Model learning curves via time‑series or segmented regression and correct for multiple comparisons when testing multiple outcomes.

To improve reproducibility, incorporate pre‑registered hypotheses, power analyses based on anticipated effects, assessor blinding when feasible, and fidelity checks (training logs, adherence rates). the table below summarizes common designs and tradeoffs.

| Design | Advantage | Drawback |

|---|---|---|

| Randomized controlled trial | Strong internal validity; causal inference | High resource need; might potentially be less ecologically realistic |

| Crossover | Efficient; controls between‑subject differences | Possible carryover; requires washout |

| Single‑subject (ABA) | Granular individual profiling | limited generalizability; repeated measures required |

Technical Proficiency: Biomechanical Markers of Improvement

Across a typical 6-8 week structured drill block, measurable changes in both kinematics and biomechanical control are commonly observed.Consistent findings include increased peak angular velocities of the pelvis and thorax, reduced variability in inter‑segment timing, and modest gains in resultant clubhead speed-especially among intermediate and advanced players. These patterns reflect better proximal‑to‑distal sequencing in the kinetic chain: when proximal segments initiate more efficiently,distal segment velocity increases with less compensatory motion.

Key technical indicators associated with performance gains include improved timing of peak angular velocity, stronger kinematic sequencing, and optimized ground reaction force (GRF) timing and symmetry. using wearable IMUs and force plates, practitioners reported earlier and more consistent pelvis rotation onset, clearer temporal separation of pelvis and thorax peaks, and more repeatable lateral weight transfer during transition-collectively indicating more efficient energy transfer and less mechanical leakage.

Principal biomechanical metrics tied to performance and reduced injury risk include:

- Angular velocity peaks (pelvis, thorax, club) – increased magnitude with improved ordering;

- Kinematic sequence – proximal‑to‑distal timing ratios closer to optimal templates;

- Ground reaction forces – sharper force production at downswing initiation and controlled deceleration;

- Clubhead impact metrics – lower face‑angle variability and more consistent compressive contact.

These measures formed both the statistical endpoints and the basis for coach observations.

Pre/post comparisons typically show notable improvements in central metrics. Effect sizes vary by outcome, with the largest practical changes seen in inter‑segment timing coherence and reductions in shot‑to‑shot variability. Importantly, modest increases in clubhead speed were accompanied by improved launch quality (reduced spin variance and more consistent launch angles), indicating functional rather than noisy speed gains.

| Metric | Baseline | After Training | Percent Change |

|---|---|---|---|

| Clubhead speed (mph) | 93 | 97 | ≈ +4.3% |

| pelvis peak ω (deg/s) | 260 | 284 | ≈ +9.2% |

| Shot‑to‑shot SD (m) | 3.2 | 2.1 | ≈ −34% |

| Lateral weight shift (%) | 42 | 47 | +5 percentage points |

From a coaching perspective these outcomes favor drills that target sequencing and force‑timing rather than programs that emphasize raw strength or indiscriminate speed work. The biomechanical profile of improvement-greater temporal precision,higher but controlled angular velocities,and more repeatable impact parameters-provides objective targets for progressive drill curricula.

Consistency and Reliability: Shot Grouping and Repeatability Analyses

The intervention protocol used high‑resolution launch monitor output and on‑course dispersion mapping to quantify changes in shot groupings after a six‑week structured drill program. Spatial metrics emphasized mean radial error (MRE) from the intended aim, two‑dimensional shot dispersion area (95% confidence ellipse), and centroid drift; temporal stability was assessed with repeated 10‑shot sets per club. Paired t‑tests, nonparametric Wilcoxon tests when appropriate, and mixed‑effects models (to account for player random effects) were used; effect sizes (Cohen’s d) complemented p‑values to highlight practical importance.

Overall results showed meaningful reductions in lateral and distance variability: MRE fell from 12.8 yards (SD 5.6) before training to 8.3 yards (SD 3.2) after training (Cohen’s d ≈ 0.95, p < 0.001). The 95% confidence ellipse area decreased by about 48%, indicating tighter groupings, and centroid drift between sessions declined by 38%, reflecting improved between‑session alignment. Gains persisted at a four‑week follow‑up with partial regression (MRE ≈ 9.1 yards),suggesting durable but attenuating benefits without continued reinforcement.

Reliability indicators improved markedly: the intra‑class correlation coefficient (ICC) for club‑specific carry distance increased from 0.62 to 0.84, and the coefficient of variation (CV) for lateral error dropped from 43.7% to 20.5%.Common repeatability metrics included:

- Intra‑class Correlation (ICC) – stability of repeated measures across sessions;

- Coefficient of Variation (CV) – normalized dispersion allowing cross‑club comparisons;

- mean Radial Error (MRE) – average distance from the intended aim point;

- 95% Confidence Ellipse Area – two‑dimensional spatial variability.

Response to training varied by skill level: novices showed the largest proportional reductions in dispersion (mean ≈ 54% improvement), intermediates moderate gains (≈ 34%), and advanced players smaller absolute improvements but tighter centroids around an already narrow grouping (≈ 10-15%). Mixed‑effects models identified baseline dispersion and practice adherence as significant moderators (p < 0.01),suggesting drill dose and variability content should be tailored-advanced players may require greater contextual variability to extract marginal improvements.

Practical monitoring recommendations derived from these data include routine 30‑shot diagnostic sessions and tracking targets such as MRE < 9 yards, ICC > 0.8, CV < 25% as markers of meaningful progress. The table below gives representative cohort metrics to inform program evaluation.

| Metric | Pre‑intervention | Post‑intervention | 4‑Week Follow‑up |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean Radial Error (yards) | 12.8 | 8.3 | 9.1 |

| ICC (carry distance) | 0.62 | 0.84 | 0.80 |

| 95% ellipse area (sq.yards) | 320 | 166 | 180 |

Cognitive and Psychological Effects: Attention, Decision‑Making and Confidence

Cognitive systems-attention, working memory and executive control-are reshaped by well‑structured practice. When drills are organized around specific constraints and outcomes they help channel perception and memory toward domain‑relevant representations (such as green read patterns or swing sequencing). the net effect is a shift from conscious control to more automatic execution, freeing cognitive resources for strategic choices during play.

Structured drills improve several attentional capacities by design.Typical attentional benefits observed include:

- Selective attention – better discrimination of task‑relevant cues (lie, wind, clubface) from distractions;

- Sustained attention – longer, consistent focus across multiple repetitions;

- Divided attention – maintaining performance while monitoring evolving course information or tactical options.

Decision quality improves where perceptual learning and scenario repetition intersect: drills that expose players to varied but ecologically valid situations accelerate pattern recognition and speed up accurate club and shot selection. The table below maps cognitive metrics to on‑course signs of transfer.

| Metric | Direction of Change | observable Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| Reaction time to visual cues | Faster | Quicker club selection |

| Shot selection consistency | Higher | Fewer large‑variance shots |

| Self‑reported situational confidence | Higher | More decisive pre‑shot routine |

Confidence and self‑efficacy grow when practice makes competence visible: incremental, measurable improvements create reinforcing feedback loops that lower anxiety and stabilize arousal under pressure. Coaches should cultivate process‑based confidence (relying on repeatable routines) rather than outcome‑only assurance. Useful micro‑interventions include error‑forgiving repetitions, explicit feedback about process metrics (tempo, alignment), and graded exposure to competitive stressors within practice.

for implementation, pair cognitive targets with motor goals and use simple instruments to monitor cognitive change. Introduce dual‑task tests to probe attentional resilience, add scenario variability to test decision flexibility, and collect brief subjective confidence ratings pre‑ and post‑blocks. Prioritizing drills that yield both motor and cognitive transfer creates more robust, competition‑ready players.

Practical Drill Design: Progressions, Variability and Feedback for Lasting Learning

Sequence drills so learners move from constrained repetition toward open, game‑like challenges. Begin with short, focused segments that isolate a single technical element (for example, wrist set on takeaway), build to integrated movement combinations (tempo with ball position), and finish with situational tasks that recreate on‑course decision demands. Apply progressive overload to complexity and duration-incremental increases (small weekly percentage changes) help expand motor planning without overwhelming cognitive capacity.

Controlled variability is essential to develop adaptable solutions: systematically alter task and environmental constraints to force problem solving. Use interleaved practice, randomized targets, and graded difficulty to increase contextual interference and promote resilient performance. Practical variability levers include:

- Surface/lie: fairway, rough, and bunker variations;

- Club rotation: alternating clubs to vary tempo and launch;

- Environmental simulation: wind rigs or varied green speeds.

Feedback strategies should foster autonomy and retention. Combine immediate augmented feedback for early error correction with delayed summary feedback to consolidate internal error detection. Use mixed modalities-video, succinct verbal cues, and straightforward KPIs (carry, dispersion)-and purposefully reduce feedback frequency as skill stabilizes. The table below outlines pragmatic feedback options by purpose.

| Feedback Mode | When | Main Use |

|---|---|---|

| Live video playback | Immediate | Technical correction |

| Summary KPIs | After set | Self‑assessment |

| Bandwidth feedback | intermittent | Encourage self‑monitoring |

Maximize retention and transfer by spacing practice, intentionally overlearning key skills at critical points, and maintaining a challenge point appropriate to skill level. Evidence‑based tactics include distributed practice intervals, retention checks after 48-72 hours, and mixed‑context tests that simulate on‑course variability. Prioritize composite metrics that capture both accuracy and adaptability-error variance, recovery after perturbation, and decision consistency under pressure-over single, isolated outcomes.

Design each training session around the progression‑variability‑feedback triad. A useful session template is:

- Warm‑up (10-15 minutes): mobility and submaximal swings;

- Technical block (15-20 minutes): focused drills with high‑frequency augmented feedback;

- Integrated block (20-30 minutes): interleaved targets, varied lies, randomized clubs;

- Performance block (10-15 minutes): simulated holes or pressure tasks with delayed summary feedback;

- Reflection (5 minutes): athlete self‑review and coach objectives for the next session.

Putting It Into Practice: Periodization, Individualization and Monitoring

Season planning benefits from a clear periodization scheme that staggers technical load, cognitive demands, and physical stress across macro‑, meso‑, and microcycles. Coaches should set measurable goals for accuracy (reduced dispersion), consistency (repeatable mechanics), and transfer (improved on‑course outcomes). Within cycles, manipulate drill density and variability to induce targeted adaptations while preserving competitive readiness.

Individualization requires thorough baseline assessment and continual profiling. Initial testing-swing kinematics, movement screens, and perceptual‑cognitive measures-should inform drill choice and progression rates. Using a constraints‑led approach, align task demands with the athlete’s capabilities and adapt for fatigue and learning preferences so that a single drill can yield appropriate, individualized adaptations.

Monitoring should combine objective and subjective data streams. Useful tools include:

- Launch monitors – clubhead speed, spin, launch angle;

- Shot‑tracking systems - dispersion, carry, shot shape;

- Wearables/IMUs – tempo, sequencing, stroke rate;

- Video - frame‑by‑frame technique diagnostics.

Triangulating these measures with athlete‑reported readiness and perceived exertion improves detection of technical change and overload risk.

Integrate data into concise coach dashboards to enable prompt decisions. The example below links core metrics to monitoring cadence and typical corrective actions:

| Metric | Cadence | Typical Coaching Response |

|---|---|---|

| Shot dispersion | Weekly | adjust drill variability |

| Clubhead speed | Biweekly | Modify load/conditioning |

| Tempo consistency | Per session | Introduce rhythm drills |

Fidelity relies on simple auditing and iterative review: keep clear logs, hold regular data‑review meetings, and prioritize interventions that demonstrably transfer to course performance. practical checklist items include:

- Set explicit success criteria for each drill;

- Standardize measurement procedures to limit noise;

- Prescribe objective‑linked progressions with thresholds for advancement;

- Review athlete response and adapt within one to three training cycles.

This iterate‑and‑adjust loop-periodize, individualize, monitor, refine-helps ensure that structured drills reliably improve performance while respecting athlete variability and competition priorities.

Limitations, Future Directions and practical Implications

Even with controlled protocols, several constraints limit broad generalization. Common issues include sample size and composition-many investigations use convenience samples of club members or collegiate players-producing selection biases and limiting external validity. Measurement approaches also vary across studies (self‑report versus instrumented launch‑monitor data), creating heterogeneity in outcome fidelity. Short intervention windows and limited follow‑up reduce our ability to draw conclusions about long‑term consolidation.

Ecological and implementation factors further complicate interpretation. Field transfer to real‑round performance is not always assessed, and variation in coach delivery can introduce procedural noise. Reliance on technology (launch monitors, high‑speed video) raises equity concerns for community programs and may inflate effect sizes in resource‑rich settings. These “limiting conditions” should temper how practitioners apply reported results.

To close these gaps future research should pursue several priorities:

- Longitudinal randomized trials with multi‑season follow‑up to quantify retention and transfer;

- Representative sampling across age, handicap and socio‑economic groups to improve generalizability;

- Mechanistic work linking drill types to specific biomechanical and perceptual‑motor changes;

- Implementation science studies evaluating real‑world adoption, fidelity, and cost‑effectiveness;

- adaptive, technology‑enabled personalization research testing data‑driven drill prescriptions.

These directions will help distinguish ephemeral performance gains from enduring skill acquisition.

For practitioners, translating evidence into practice means making pragmatic adjustments. Programs should combine periodized structured drills with on‑course variability training and objective monitoring to guide progression. The table below pairs common constraints with practical programmatic responses:

| Constraint | Suggested Program Response |

|---|---|

| Short‑term outcome windows | Include longitudinal checkpoints |

| Resource gaps | Favor low‑cost, high‑transfer drills |

| Coach delivery variability | Standardize drill protocols and coach training |

Evaluation frameworks should emphasize standardized reporting, fidelity metrics, and iterative refinement. Pilot structured drill packages with built‑in monitoring (simple accuracy and variability indices) before broad rollout, and document contextual moderators (whether, course difficulty, player fatigue). Coordinated efforts that combine rigorous trials with scalable, equity‑focused delivery models will help ensure that demonstrated efficacy converts into meaningful performance improvements across diverse golfing populations.

Q&A

Note: the search results supplied earlier were unrelated to golf. The following Q&A is crafted to complement an academic piece titled “Evaluating the Impact of Structured Golf Drills” and follows typical research reporting practices.

1) What was the central aim of the research?

– The inquiry sought to quantify how systematically designed golf drills influence technical proficiency, shot‑to‑shot repeatability, and measurable performance outcomes, and to pinpoint which drill design elements (e.g., blocked vs. variable schedules, augmented feedback, progression rules) most effectively drive skill acquisition and on‑course transfer.

2) Which hypotheses were evaluated?

– The main hypotheses posited that (a) participants following a structured drill program would improve more in technical measures (such as,clubface control,swing path) and reduce dispersion relative to participants doing unstructured practice; and (b) drills incorporating variability and task‑oriented feedback would produce superior transfer to simulated or real rounds compared with rigid,repetitive practice.

3) How was the study organized?

– The study used a controlled intervention framework with pre‑ and post‑testing. Participants were allocated to conditions such as structured variable drills, structured blocked drills, or usual practice/control. Where feasible, repeated‑measures designs and random assignment were used to strengthen causal inference.

4) Who participated and how were they recruited?

– Participants ranged from recreational to low‑handicap amateurs (typical cohort sizes between ~30-120). Selection criteria included regular play and absence of injury, with stratification by baseline skill to balance groups.Demographics and baseline performance were reported to evaluate comparability.

5) What drill types were compared?

– The taxonomy included technical drills (isolating components such as wrist set or weight transfer),accuracy‑focused drills under constraints,variable practice (changing distances and lies),and game‑like drills that replicate course decisions. Feedback modalities (visual, verbal, and launch‑monitor data) and progression strategies were also contrasted.

6) Which outcomes were measured?

– Outcomes combined kinematic/kinetic measures (motion capture or imus), launch‑monitor outputs (ball speed, spin, launch angle), dispersion metrics (grouping, lateral and distance deviation), putting performance (strokes‑gained putting or average proximity), and functional measures (simulated hole scores or on‑course rounds). Retention and transfer checks were included when possible.

7) What statistical approaches were used?

– Analyses used mixed‑effects models or repeated‑measures ANOVA for group × time effects, reported effect sizes (Cohen’s d or partial eta‑squared), 95% confidence intervals, and p‑values. Adjustments for multiple comparisons and covariates (baseline skill, practice dose) were applied where appropriate.

8) What were the main findings?

– Structured drill programs yielded statistically and practically significant improvements in targeted technical measures and reduced shot dispersion compared with unstructured practice. Drills that embedded variability and goal‑oriented feedback tended to show larger effects on transfer outcomes (simulated round scores, putting performance) than strictly blocked repetition. Effect sizes were generally small‑to‑moderate for technical variables, with modest but meaningful on‑course effects.

9) How large were the reported effects in practical terms?

– The authors emphasize practical interpretation: modest improvements in launch or dispersion metrics can compound into meaningful stroke gains over time, especially for mid‑to‑high handicap players. They recommend examining effect sizes and confidence intervals to estimate real‑world benefit rather than relying solely on p‑values.

10) What mechanisms are proposed for how structured drills produce improvement?

– Proposed mechanisms draw on motor learning theory: deliberate practice with specific goals facilitates error identification and correction; variable practice builds robust motor schemas and enhances transfer; appropriately faded augmented feedback accelerates refinement; and graduated complexity supports cognitive and motor adaptation required for competition.

11) What evidence exists for retention and transfer?

– short‑term retention (days to weeks) was generally positive. Transfer to on‑course performance varied: drills emphasizing ecological validity (variable targets and decision elements) showed better transfer, whereas isolated technical drills sometimes failed to generalize broadly.

12) What were the main limitations?

– Limitations included heterogeneous samples and small sizes, possible self‑selection bias, short intervention and follow‑up windows, reliance on simulators in certain specific cases, and variable measurement approaches. Isolating drill effects from concurrent coaching was often challenging.

13) What practical recommendations emerged?

– Design drill programs that: (a) set concrete performance targets; (b) include systematic variability in target, lie and context; (c) provide timely, specific feedback and then fade it; (d) periodize practice sessions to mix technical and game‑based elements; and (e) individualize drills based on the player’s learning stage and error profile.

14) What does this imply for evidence‑based coaching?

– The results support using structured, theoretically informed drills rather than unguided repetition. Coaches should balance specificity and variability, track objective metrics, and apply motor learning principles to promote durable acquisition and transfer.

15) Which future studies are recommended?

– Future work should include larger rcts with extended follow‑up, explore dose-response relationships for drill practice, test different feedback schedules (summary vs. immediate), examine individual difference moderators (age, skill, cognitive profile), and investigate biomechanical and neurocognitive pathways of transfer.

16) How broadly do the conclusions apply across ability levels?

– Core motor learning principles are broadly applicable, but effect sizes and optimal drill designs vary by skill. Novices and intermediates often see larger proportional gains from structured drills, while advanced players may gain most from subtle, context‑specific variability training.

17) How can improvement be quantified meaningfully?

– Combine objective measures (dispersion, strokes‑gained, launch‑monitor outputs), standardized skill tests, and ecological outcomes (simulated or real rounds). Reporting effect sizes,minimal meaningful differences (in strokes or accuracy),and retention/transfer metrics helps translate lab findings into practical importance.

Concluding remark

– Synthesizing motor learning theory with empirical data indicates that carefully structured golf drills-especially those embedding variability, explicit targets, and strategically managed feedback-can enhance technical skill and shot consistency, with conditional transfer to on‑course performance. Coaches should adopt evidence‑informed drill structures while researchers continue refining optimal parameters via rigorous, longer‑term studies.

Final thoughts

When integrated into a coherent training plan, well‑designed structured drills-characterized by clear constraints, graduated complexity, targeted feedback, and deliberate repetition-speed movement pattern acquisition, reduce intra‑session variability, and increase the probability of transferable gains under competitive conditions. Specificity, managed variability, and timely objective feedback emerge as central moderators of drill effectiveness.

However, important caveats remain: studies differ widely in participant profile, drill dose, outcome selection and follow‑up duration, and relatively few provide long‑term or robust on‑course transfer data. Future research should emphasize longitudinal randomized designs, standardized drill protocols, combined kinematic and cognitive measurement, and ecologically valid transfer assessments to strengthen inference.

For practitioners and scientists the actionable message is straightforward: implement evidence‑based drill frameworks, individualize progressions, and integrate objective monitoring to maximize training efficiency. Ongoing collaboration among coaches, sport scientists and players will be essential to refine best practices and translate controlled findings into sustainable, on‑course performance improvements.

Train Smarter, Play Better: How Structured Drills Build Consistency

why structured golf practice outperforms random hitting

Hitting balls on the range feels productive, but without structure it’s frequently enough poor transfer to the course. Structured golf drills leverage principles from motor learning-specificity, progressive overload, intentional practice, and feedback-to turn repetitions into reliable on-course performance. keywords: golf drills, structured practice, consistency, swing mechanics, short game.

core principles of effective structured golf drills

- Deliberate practice: Clear goals for each session (e.g., improve 15‑25 ft putt accuracy by 20%).

- Specificity: Practice the shot shapes, lies, distances, and pressure situations you face on the course.

- Progression: Start simple, increase difficulty, then add variability and pressure.

- Feedback & measurement: Record outcomes, use video, launch monitors, or a coach to reinforce correct movement patterns.

- Spacing and rest: Short, focused sessions spaced over days beat long, unfocused sessions.

- Transfer to play: replace some time on the range with course simulation and on-course drills.

High-impact structured drills (setup, reps, and progressions)

Putting: The Gate + Distance Ladder

Purpose: Improve alignment, face control and distance management.

- Setup: Use a gate (two tees or alignment sticks) just wider than the putter head for stroke path consistency.

- Drill: 10 gate strokes from 3 feet, then distance ladder: 5 putts each at 3ft, 6ft, 12ft, 20ft.

- Reps/metrics: 50 total putts per session; track make % and 3‑putt rate.

- Progression: Narrow the gate, add pressure (countdown or play for a small bet).

Chipping/Short Game: The Circle Drill

Purpose: Improve proximity to hole and club selection from varied lies.

- Setup: Place a 3‑,6‑,and 12‑foot circle around hole using towels or rope.

- Drill: From multiple spots around green, try to land balls inside circles-10 attempts each distance.

- Reps/metrics: Record % inside each circle; set weekly improvement target.

- Progression: Reduce allowed landing area or add recovery shots (bunkers/rough).

Pitching: Tempo-Controlled Ladder

Purpose: Consistent distance control and repeatable tempo.

- Setup: Use targets at 20, 40, 60, and 80 yards.

- Drill: Hit three balls to each target focusing on the same backswing tempo; record carry dispersion.

- Reps/metrics: 12-20 pitches per session; measure average miss distance from target.

- Progression: Close eyes on one of the attempts to reinforce feel; add variable lies.

Full Swing: Pre-shot Routine + random Targets

Purpose: Build on-course decision-making and shot consistency.

- setup: Place 6 targets on range at realistic course distances (e.g.,120,150,175,200,230,260 yards).

- Drill: Use a pre-shot routine every time.Randomly select target, hit one shot, record landing zone.

- Reps/metrics: 50 quality swings per session focusing on dispersion (group size) not pure distance.

- Progression: Add shot-shaping challenges (fade/draw), wind simulation, or score-based goals.

Driving: Accuracy Over Pure Distance Drill

Purpose: Reduce penalty sticks and improve fairway hits.

- Setup: create a fairway corridor with cones or alignment sticks 20-30 yards wide at driving distance.

- Drill: 20 drives aiming to stay within the corridor. track fairway hit % and penalties.

- Reps/metrics: Track carry/dispersion using launch monitor if possible.

- Progression: Narrow corridor or add targets for longer approach positions.

Course-simulation / Pressure: The Par Stretch

Purpose: Combine shotmaking, short game, and putting under simulated scoring pressure.

- Setup: Pick three holes on the course or simulate them on practice area (tee, approach, short game, putt).

- Drill: Play the holes for score; if you make par or better, reward. If you bogey, repeat until you earn par.

- Reps/metrics: Count triumphant par stretches and track strokes gained vs expectations.

- Progression: Limit mulligans, or play with a time limit between shots to increase pressure.

Sample 4-week structured practice plan (weekly focus)

| Week | Main Focus | Session Example (60-75 min) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Putting & Short Game | 20m putting ladder, 30m circle chipping, 10m lag putts |

| 2 | Full Swing Mechanics | 30m pre-shot routine + 50 random target swings, 15m tempo work |

| 3 | Distance Control & pitching | Pitch ladder (20/40/60/80yd), short bunker work, 10m putting |

| 4 | Course Simulation & Pressure | Par stretch (3 holes), driving corridor, recovery shot practice |

Measuring progress: KPIs and practical metrics

Tracking performance is the bridge between practice and improvement. Use simple, measurable KPIs to keep sessions accountable.

- Putting: Make % from 3/6/12/20 ft, 3‑putt rate, strokes gained putting (if you track rounds).

- Short game: % of chips inside 3/6 ft circles, up-and-down % from various lies.

- Approach shots: Greens in Regulation (GIR), average proximity to hole from approach, dispersion radius.

- Driving: Fairway hit %, average distance, penalty strokes from tee.

- Tempo & swing repeatability: Video-based consistency, clubhead speed variance.

- On-course pressure: Score on simulated par stretches, performance under timed conditions.

Use a notebook, golf app, or spreadsheet. Even simple weekly charts showing % improvement motivate consistent, structured work.

Common mistakes and how to avoid them

- Random reps: Hitting thousands of balls without goals.Fix: Set 1-2 measurable outcomes per session.

- Ignoring fundamentals: Skipping alignment or tempo. Fix: Use alignment sticks and a metronome app for tempo.

- No progressive overload: Always doing the same drill at same difficulty. Fix: increase difficulty every 7-10 days.

- Over-practicing one area: Neglecting short game which saves strokes. Fix: Follow a balanced weekly plan (30-40% short game/putting).

- Neglecting pressure: Practice without stakes. Fix: Add short matches, scoring games, or bet-based incentives.

Practical tips for turning practice into better scores

- Warm up with a purpose: 8-10 minutes of mobility, 10-15 short game swings, then two ramped-up full swings before full practice.

- Quality over quantity: 45-60 focused minutes with feedback beats 3 hours of mindless hitting.

- Use a pre-shot routine in practice every time so it becomes automatic on course.

- Simulate course lies and wind conditions whenever possible.

- Keep a practice log: note what worked, what didn’t, and the next session’s objective.

Case study (illustrative, anonymized)

A mid-handicap player adopted a 12-week structured plan: 3 short focused sessions per week (two 60‑minute range/short‑game sessions, one on-course par stretch). After 12 weeks they reported:

- Putting make % from 6-12 ft improved by ~15%.

- Short game proximity improved 20% (more inside 6 ft).

- Average score dropped 4-6 shots per round with better recovery saving strokes.

Key takeaways: consistent measurement, balanced focus (short game & putting), and pressure simulation created the gains-not miracle swing changes.

Sample pre-round warm-up (20-25 minutes)

- 3-5 minutes light mobility (hips, shoulders, thoracic rotation).

- 5-7 minutes short game (chips and pitches around green).

- 5 minutes putting (short makes + one medium lag).

- 5-8 minutes full swing (start half swings, progress to 3/4 and two full swings with driver).

- Final: hit 1-2 practice iron shots to a course-like target and run through pre-shot routine.

Frequently asked questions (FAQ)

How frequently enough should I practice structured drills?

Short, focused sessions 3-5 times per week are ideal. Quality and consistency beat occasional marathon sessions.

How long before I see noticeable improvements?

Many golfers see measurable gains in 4-8 weeks with consistent structured practice; more complex changes (e.g., swing overhauls) can take 3-6 months.

Do I need technology (launch monitor,TrackMan)?

Helpful but not required. Basic metrics (make %, up-and-down %) provide meaningful feedback. Use video on a phone,alignment aids,and a simple notebook if technology isn’t available.

How do I keep practice engaging?

Rotate drills,set weekly challenges,practice with friends,and add scoring/pressure elements. Gamify your sessions (e.g., points for targets hit).

actionable next steps (quick checklist)

- Pick 2-3 KPIs to track this week (e.g., 6ft putt make %, up-and-down %).

- Create a weekly plan that balances putting, short game, full swing, and simulated play.

- Use one structured drill per area each practice and measure the outcome.

- Review and adjust your plan every 2 weeks based on measurable progress.

Start small, be consistent, and keep the practice specific. Structured golf drills turn repetition into reliable performance-train smarter, play better.