The follow-through segment of the golf swing is the consecutive motion that begins the instant after ball contact and completes the kinetic sequence that produced the shot. The ordinary meaning of “follow” – to come after in time or sequence – helps frame the follow-through as a distinct yet continuous stage whose features both reveal and affect the mechanics that preceded it. Far from being a cosmetic finish, the follow-through offers insight into timing, efficiency of energy transfer, and neuromuscular control, so it deserves focused biomechanical study for players and coaches pursuing reproducible performance.

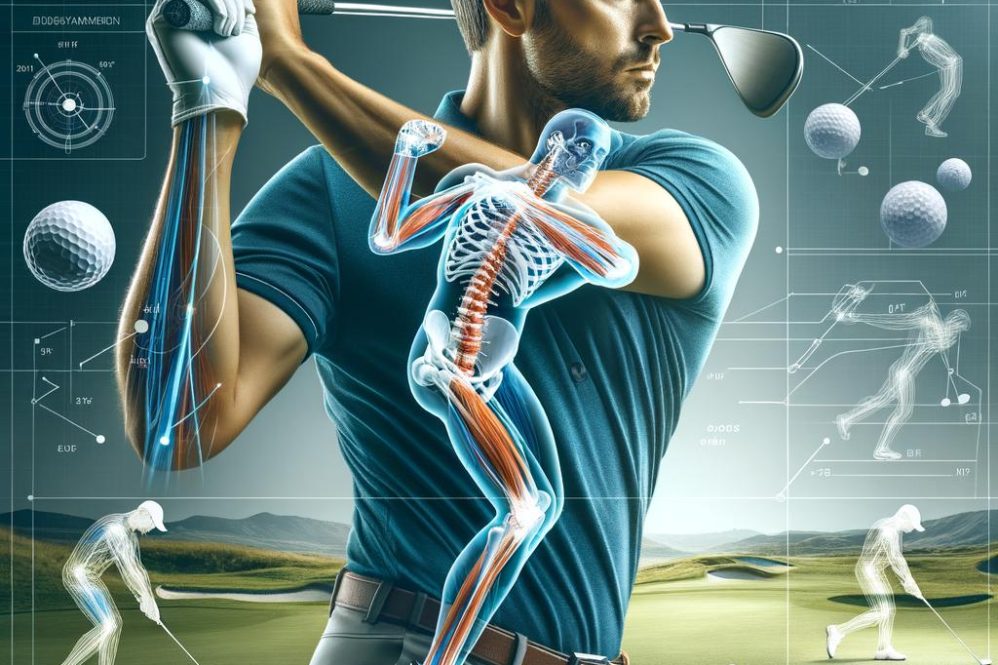

This revised review consolidates modern biomechanical concepts relevant to refining the follow-through. It highlights coordinated segment sequencing (proximal-to-distal activation), angular momentum management, modulation of ground reaction forces, and joint kinetics across hips, trunk, shoulder, elbow and wrist. Quantitative markers – segmental angular speeds, joint excursions, and timing offsets – are interpreted with respect to practical outcomes such as shot direction, launch conditions and dispersion. The narrative also examines sensorimotor integration and neuromuscular coordination that sustain stable follow-through patterns.Interplay between planned motor commands (feedforward), proprioceptive feedback and reflexive stabilizing reactions determines how the swing adapts to changing conditions (different lies, intended shot shapes, or fatigue).Muscle recruitment strategies – combined concentric drives and graded eccentric braking through the legs, core and upper limb – both generate and absorb forces to keep the body balanced, limit harmful loading and maximise repeatability.

The material below links these scientific perspectives with day-to-day coaching and rehabilitation practise. Practical evaluation methods, drill progressions and objective performance metrics are offered so biomechanical insights can be translated into effective training plans. By bridging theory and request, the following sections aim to support evidence-based approaches for improving follow-through mechanics that boost accuracy, repeatability and athlete durability.

Kinematic Principles Underlying the Follow-Through

Analyzing the follow-through is best done within a kinematic framework that prioritises spatiotemporal descriptors – position, velocity and acceleration – rather than force in isolation. Think of the swing as a chain of linked segments where joint angles and segment rotations define the instantaneous geometry of the clubhead trajectory. Tracking the time-series of segment orientations (pelvis, thorax, humerus, forearm and clubshaft) reveals adherence to a swing plane, changes in rotational radius and the onset of secondary motions that increase dispersion. Distinguishing what the system does (kinematics) from why it does it (dynamics) allows targeted technical changes without assuming internal loading magnitudes.

Primary kinematic variables that shape an effective follow-through include:

- Pelvic and thoracic angular velocities – the timing between hip and torso turn that enables efficient momentum transfer.

- Proximal‑to‑distal sequencing – ordered peaks in angular velocity progressing pelvis → trunk → upper arm → forearm → club.

- Joint configurations – wrist extension, elbow flexion/extension and shoulder rotation that establish the release geometry.

- Clubhead speed and path curvature – the end kinematic outputs most closely tied to ball speed and shot scatter.

- Post‑impact deceleration rates – angular and linear slowing that indicate controlled energy dissipation and potential injury risk.

| Segment | Peak Kinematic Event | Typical Timing (% of cycle) |

|---|---|---|

| hips | Rotation onset / peak velocity | 35-50% |

| Torso | Peak angular velocity | 50-70% |

| Wrists & Club | Maximum linear velocity (release) | 80-95% |

Turning kinematics into safer, more consistent performance rests on two practical tenets.First, maintaining a coordinated proximal‑to‑distal sequence concentrates peak speeds at the clubhead instead of at fragile distal joints. Second, practising controlled deceleration via progressive eccentric muscle work reduces peak joint loads during the follow-through. from a coaching viewpoint this translates into cueing the timing of hip versus thorax rotation, observing wrist unhinging speed, and building eccentric strength in the lead arm and trunk to manage braking after impact.Objective tools – high‑frame‑rate video, optical motion capture and wearable inertial sensors – make these kinematic indicators measurable, enabling evidence‑based technical revisions that raise consistency and lower overload risk.

Timing, Ground Interaction and Momentum Flow

Transferring rotational energy efficiently begins with a well‑timed cascade of segment accelerations that start at the feet and travel upward through the hips, trunk and shoulders to the arms and clubhead. At elite levels, the proximal‑to‑distal pattern produces sequential angular velocity peaks – hip before trunk, trunk before shoulder – maximizing clubhead speed while reducing internal joint stress. The brief time lags between these peaks are functional intervals that allow angular momentum to add constructively; compressing or stretching them changes launch conditions and dispersion. Measuring these latencies with high‑speed capture gives clear technical targets for correction.

The ground provides the external moments that initiate this chain: deliberate application of ground reaction force (GRF) and orderly center‑of‑pressure (CoP) transition create the torque that starts pelvic rotation and the downstream sequence. Typical empirical windows for these events are summarised below:

| Phase | Typical Timing (relative to impact) | primary Mechanical Role |

|---|---|---|

| Lead-leg brace | ~150-50 ms before impact | Transmit GRF, stabilize pelvis |

| Pelvic peak | ~80-40 ms before impact | Initiate proximal rotation |

| Trunk/shoulder peak | ~40-10 ms before impact | Amplify angular velocity distally |

Angular momentum transfer follows conservation laws but is shaped by intersegmental torques and joint stiffness: as the pelvis decelerates under eccentric control, its momentum is redistributed to the trunk and upper limb segments, accelerating them in turn. Indicators of efficient transfer include clear sequential velocity peaks, moderate intersegmental torque impulses and preserved timing across different swing speeds. Coaching cues rooted in these mechanics stress proximal stability with distal freedom – stabilise the lead lower limb and allow a swift, relaxed release of wrists and forearms at the chain’s end.

Because abrupt or poorly timed deceleration elevates tissue load,controlled eccentric braking is critical for both accuracy and durability. Training should therefore include neuromuscular exercises to boost eccentric capacity in hip rotators, trunk extensors and upper‑limb decelerators, together with perturbation drills to refine CoP shifts. Monitoring metrics such as peak angular velocities, sequencing intervals and GRF onset helps guide progressive overload safely. Field‑practical interventions - plyometric ground‑force drills, tempo‑resisted rotations and deceleration‑focused swings – translate these biomechanical principles into measurable gains in consistency and longevity.

neuromuscular Patterns That Shape the Finish

The follow-through is the final expression of a coordinated neuromuscular strategy where timing, sequencing and graded muscle activation determine weather a shot is repeatable. A proximal‑to‑distal activation cascade is central: hip extension and pelvic rotation launch momentum,the thoracolumbar complex modulates rotational speed and stabilises the torso,and shoulder,elbow and wrist muscles refine club path and release. Electromyography (EMG) is routinely used in research to quantify these temporal relationships and to identify maladaptive activation patterns that compromise performance or raise injury risk.

Distinct muscle groups assume predictable roles with characteristic activation windows around impact; the table below summarises common functional patterns seen in laboratory studies. Timing is shown as a relative window around contact (0 ms) to emphasise coordination rather than absolute values, which vary by individual and club choice.

| Muscle Group | Functional Role | Relative Activation window |

|---|---|---|

| Gluteals / Hamstrings | Generate ground force, rotate pelvis | Initiation: -60 to -20 ms |

| Obliques / Erector spinae | Transfer torque, stabilise trunk | Pre‑impact peak: -30 to +40 ms |

| Rotator cuff / Deltoids | Arm acceleration and face control | Acceleration: -10 to +60 ms |

| Forearm flexors & extensors | Manage release and deceleration | Peak after impact: +20 to +120 ms |

Neuromuscular control during the follow‑through combines preprogrammed activations with rapid feedback adjustments. Typical experimentally observed strategies include anticipatory activation of postural muscles, selective co‑contraction around the shoulder for stability during high‑speed release, and controlled eccentric actions in distal muscles to slow the club safely. Common measurement and training tools used to assess or alter these patterns are:

- Surface and fine‑wire EMG for timing and amplitude insights into muscle activity.

- Force plates to quantify lower‑limb contribution and sequencing of GRFs.

- 3D motion capture with inverse dynamics to relate muscle output to segment motion.

- Perturbation and tempo drills to strengthen feedforward stability and timing robustness.

from a practical and clinical standpoint, optimising neuromuscular patterns requires staged interventions: technical drills to reinforce desired sequencing, neuromuscular conditioning to raise rate of force development and eccentric capacity, and instrumented assessment (e.g., EMG) when pain or performance deficits suggest underlying dysfunction. Emphasise task‑specific overload (tempo and resistance variations), graded speed exposure, and variability in practice to consolidate adaptable motor programs – each approach targets the neural bases of timing and coordination necessary for dependable follow‑through mechanics.

Sensory Integration, Proprioception and Consistency

How sensory channels are combined during and immediately following impact plays a decisive role in shot consistency. Vision, vestibular inputs and somatosensory feedback together inform the nervous system about clubface orientation, body rotation and balance; these signals constrain corrective motor responses and contribute to longer‑term motor memory. The nervous system weights these inputs by their reliability: visual cues strongly affect lateral dispersion while proprioception tends to govern fine temporal adjustments needed for deceleration.

Proprioceptive accuracy depends on coordinated input from muscle spindles, Golgi tendon organs and joint receptors, interpreted in the context of an internal copy of the motor command (efference copy). As afferent feedback is delayed,robust feedforward programming of braking is vital,but closed‑loop corrections during the follow‑through can still polish launch variables when sensory information is dependable. Training that sharpens receptor sensitivity and sensorimotor integration improves both rapid corrective responses and trial‑to‑trial consistency:

- Eyes‑closed drills to heighten reliance on somatosensory cues and sharpen limb‑position sense.

- Perturbation training (unstable surfaces or resistance bands) to strengthen vestibular‑somatosensory coupling.

- Variable practice to build adaptable sensorimotor mappings across differing contexts.

- Intermittent haptic and video feedback to promote error‑based learning while avoiding dependency.

To make physiology actionable, the table below links common receptors with practical drills that address their primary contributions:

| Sensor | Primary contribution | Sample drill |

|---|---|---|

| Muscle spindles | Velocity and timing of deceleration | Quick swing‑to‑stop repetitions |

| Golgi tendon organs | tension regulation for release control | Resisted follow‑through practice |

| Vestibular apparatus | Balance and trunk orientation | Single‑leg finish holds |

From a motor‑control viewpoint, improving follow‑through precision requires balancing predictive feedforward schemas with measurable feedback corrections. practitioners should emphasise closed‑loop refinement during early learning and judiciously fade augmented feedback as skill improves to prevent reliance. Programmatically, this involves gradually reducing external feedback frequency, incorporating perturbation and sensory‑deprivation tasks to fortify internal models, and tracking consistency metrics (e.g., launch‑angle variability) to safely increase sensorimotor challenge.

Late‑Swing Variables: Face, Path and Initial Ball Conditions

The final 50-100 ms before impact have an outsized effect on the ball’s initial state: clubface angle primarily sets initial direction, while the club path relative to that face dictates sidespin and curvature.Small shifts in trunk rotation timing or wrist pronation during this window alter the face‑to‑path relationship and therefore launch direction, spin axis and sidespin magnitude, even when gross swing geometry seems unchanged. disentangling these micro interactions is crucial for diagnosing whether dispersion stems from face control or path inconsistencies.

Core mechanical variables to evaluate and train include:

- Club path (in‑to‑out, neutral, out‑to‑in): biases the tendency to draw or fade.

- Face orientation (open, square, closed relative to path): determines initial direction and spin sign.

- Attack angle and shaft lean: influence effective loft and spin loft,altering launch angle and backspin.

These factors interact nonlinearly. For exmaple, a marginally closed face on an out‑to‑in path can create a severe pull‑hook rather than a simple pull as coupled changes in spin axis and side spin magnify the effect.

in practice,complementary measurement tools – high‑speed impact video,radar launch monitors and marker‑based motion capture - help isolate face versus path contributions.Coaching should blend objective data with targeted motor‑learning exercises emphasising the timing of trunk rotation relative to arm extension and wrist set. Practical drills include shadow swings with an alignment rod to rehearse face‑square positions, impact tape to link strike location and face rotation, and slow‑motion reps with metrical auditory cues for pronation timing to retrain the final 0.1-0.2 seconds before contact.

| Club Path | Face vs Path | Typical Ball Flight |

|---|---|---|

| In‑to‑out | Face open to path | Push‑slice / Fade |

| Neutral | Face square | Straight |

| Out‑to‑in | Face closed to path | Pull‑hook / Draw |

Refining the late‑swing sequence so the face‑to‑path relationship is predictable – via coordinated trunk turn, arm extension and wrist control – reduces launch variability and improves accuracy across shot types.

Load Management and Injury Prevention at the Finish

Controlling mechanical loads during the final swing phases is essential for both performance and preventing overuse injuries. Tissue tolerance – the load‑bearing capacity – differs across the shoulder complex, lumbar spine and wrist; directing momentum dissipation through larger, more resilient structures lowers peak stress on smaller tissues. Mechanically, the follow‑through should emphasise graded eccentric deceleration of hips and torso to absorb angular momentum rather than an abrupt arrest at distal segments. This redistribution protects neuromuscular health and preserves repeatability during high session volumes.

Practitioners should apply strategies to manage both acute and cumulative loading. Vital elements include:

- Gradual exposure – progressively increase swing intensity and volume to raise local tolerance.

- Sequencing focus – train proximal‑to‑distal transfer so trunk eccentrics absorb late‑phase energy.

- Movement variability – vary finish postures slightly to avoid repetitive point‑loading.

Thinking in terms such as joint‑specific “load on” and an overall load factor (demand per swing) helps plan practice and recovery cycles intelligently.

| Structure | Dominant Load Type | Targeted Mitigation |

|---|---|---|

| Lead shoulder | Rotational shear & eccentric tension | Eccentric rotator‑cuff conditioning |

| Lumbar spine | Axial compression + shear during deceleration | Core bracing and hip mobility work |

| lead wrist | Impact‑induced torque | Grip modulation & progressive overload |

Implementation relies on objective monitoring and customised load‑control protocols. Use wearable outputs (peak angular velocity,deceleration impulse),session counts and symptom tracking to steer progression; prioritise eccentric strengthening and neuromuscular drills that raise the effective capacity of vulnerable tissues. Recovery planning – sleep, nutrition and active regeneration – should be built into periodised programmes to reduce cumulative microtrauma. Cross‑disciplinary collaboration among coach, physiotherapist and strength specialist ensures that technique, conditioning load and any symptoms are integrated into a coherent, evidence‑based strategy for long‑term performance and injury reduction.

Evidence‑Backed drills and Progression Models

Research supports treating the follow‑through as the measurable result of coordinated kinetic‑chain sequencing rather than an isolated aesthetic finish. High‑fidelity measures (3D capture, force plates, surface EMG) consistently associate trunk rotational speed, controlled arm extension and timed wrist pronation with launch‑angle repeatability and lateral dispersion. Training should therefore convert laboratory markers into field‑ready drills that cultivate reproducible joint kinematics, intersegmental timing and efficient energy transfer while minimising compensations commonly seen in developing players.

Choose drills that are specific,measurable and scalable. Examples with practical coaching cues include:

- Mirror‑Finish Drill – slow full‑swing finishes focused on terminal trunk rotation and clubface alignment to strengthen proprioceptive feedback;

- Med‑ball Rotational Throws – short, powerful rotations emphasising rapid trunk‑to‑arm transfer to build angular velocity without overtaxing distal joints;

- Progressive Half‑to‑Full Swings – gradually increase swing length and speed to ingrain correct timing of extension and pronation;

- resistance‑Band Pronation Rolls – resisted pronation exercises at follow‑through positions to reinforce distal motor patterns;

- Tempo Metronome – rhythmically paced swings to stabilise intersegmental sequencing and prevent late‑arm dominant finishes.

Each drill should be paired with a clear kinematic cue and a measurable target (angles, velocities or perceived effort) to support objective progression.

progress should follow a three‑stage model that merges motor learning with load control. The table below gives a compact framework for planning individual or small‑group sessions suitable for coach portals or athlete logs:

| Phase | Primary Focus | Example Prescription |

|---|---|---|

| Foundation | Motor control, alignment, low‑load timing | 3×/week: 6-10 slow reps per drill, video feedback |

| Integration | Speed development, coordinated power transfer | 2-3×/week: med‑ball + progressive swings, 8-12 reps, load progression |

| Performance | Competition tempo, fatigue resilience | 1-2×/week: high‑speed swings, situational practice, monitoring |

Objective monitoring drives safe and effective advancement. Trackable criteria should include peak trunk rotational velocity, clubhead speed, wrist pronation angle at impact and 0.1-0.2 s afterward, and intersegmental timing offsets (e.g., pelvis‑to‑trunk peak lag). Use simple pass/fail thresholds to move between phases (for example: consistent pronation angle within ±5° across 10 trials; an ≥8% trunk rotational velocity increase from baseline without accuracy loss). Adjust volume and complexity based on fatigue indicators and accuracy outcomes. Pair quantitative targets with regular qualitative video review and a short coach checklist:

- Was the finish reproducible?

- Was face alignment within acceptable tolerance?

- Was pelvis → trunk → arms sequencing preserved?

This evidence‑driven, progressive approach fosters neuromuscular adaptation while reducing the chance of technique breakdown under competitive demands.

Q&A

Below is a practical Q&A to accompany “Follow‑Through Biomechanics for Golf Swing Mastery.” It covers definitions, key biomechanical concepts, measurement and assessment methods, training strategies, motor‑learning considerations and injury prevention. As a reminder,the word “follow” implies succession in time or sequence – a useful anchor for viewing the follow‑through as the post‑impact stage that completes energy transfer and stabilises movement.

Q1. What exactly is the follow‑through and why does it matter biomechanically?

A1. The follow‑through begins immediately after impact and continues untill the final balanced posture. Biomechanically it signals completion of kinetic‑chain energy transfer, controlled braking of distal segments, stabilisation of the body’s centre of mass and safe dissipation of forces. A mechanically efficient follow‑through both reflects upstream sequencing and supports shot repeatability and injury prevention.

Q2.Which biomechanical principles are central to an effective follow‑through?

A2. Essential elements include (1) proximal‑to‑distal sequencing of angular velocities, (2) conservation and controlled redistribution of angular momentum, (3) use of ground reaction force and weight transfer to support rotation, (4) eccentric muscular deceleration to dissipate energy safely, (5) balance and centre‑of‑pressure management, and (6) sensorimotor feedback to fine‑tune outcomes in real time.

Q3. How does downswing sequencing influence the follow‑through?

A3. Downswing sequencing sets the momentum and segmental velocity pattern that must be continued and decelerated through the follow‑through. A correct proximal‑to‑distal sequence produces predictable peak velocities leading to efficient clubhead speed and a controlled finish. Mistimed sequencing (early arm dominance or delayed hip turn) alters impact mechanics and produces compensatory follow‑throughs that reduce accuracy and raise injury risk.

Q4. What muscles are most important for producing and controlling the follow‑through?

A4. key groups are hip extensors and rotators (glutes, hamstrings), trunk rotators and stabilisers (obliques, transversus abdominis, erector spinae), scapular stabilisers and rotator cuff muscles, and forearm/wrist muscles for deceleration and grip control. Eccentric capacity in trunk and upper limb muscles is particularly important for safe braking after contact.

Q5. What does a biomechanically sound finish typically look like?

A5.Common features include considerable thorax rotation toward the target, pelvis rotated with weight on the lead leg, a stable (slightly flexed) lead knee, the club wrapped across or behind the chest/shoulder region, the head naturally following trunk rotation, and the ability to hold a balanced finish for several seconds, often on the lead leg.

Q6. In what ways does the follow‑through affect shot precision and consistency?

A6. The follow‑through is both diagnostic and formative: a repeatable, biomechanically sound finish indicates consistent upstream sequencing and impact conditions, improving accuracy. Training a balanced, mechanically correct finish also helps embed motor patterns that stabilise clubface orientation and path at impact.

Q7. Which objective measures are useful for assessing follow‑through quality?

A7. Useful metrics include kinematic sequencing indices (timing and magnitude of pelvis, thorax, shoulder and wrist peaks), finish rotation angles, GRF magnitude and timing, CoP trajectory, clubhead path and face angle at impact, EMG profiles for timing and eccentric control, and balance measures (time‑to‑stabilisation, hold duration). portable IMUs and high‑speed video work well in the field; force plates and EMG provide laboratory‑level detail.

Q8. What common follow‑through faults occur and what typically causes them?

A8. Frequent faults:

– Early truncation of the finish (abrupt stop): often from insufficient momentum or weak deceleration capacity, reducing distance and timing.

– Excessive forward collapse or over‑rotation: may indicate lead‑hip overuse or compensation,risking lumbar shear.

– Hanging back on the trail leg: frequently enough from inadequate hip turn or fear of forward weight shift, reducing power and promoting a slice.- Excessive arm dominance (casting or early release): typically from poor proximal sequencing and gives inconsistent face control.

Q9. Which drills target follow‑through improvement?

A9. Effective options:

– Pause‑at‑finish: hold a balanced finish for 3-5 seconds to train stability.

– Step‑through drill: step toward the target in the follow‑through to emphasise weight transfer.- Medicine‑ball rotational throws: build explosive proximal‑to‑distal sequencing and trunk deceleration.

- Towel‑under‑arm: maintain connection and prevent arm separation.

– Slow‑motion tempo drills: reinforce timing and eccentric control through the finish.

Q10. How should follow‑through training be periodised?

A10. Begin with low‑velocity, high‑feedback technical re‑education to establish motor patterns.Progress to moderate intensity with resisted work (med‑balls, tempo swings), then to full‑speed practice emphasising transfer under fatigue and variability. Integrate strength and eccentric trunk/hip conditioning early and maintain it.Schedule higher technical volume off‑season and specificity as competitions approach.

Q11. How does motor learning theory guide follow‑through coaching?

A11.Motor learning suggests external focus instructions (e.g., “turn shoulders to the target”) promote better automaticity than internal cues. Variable practice (different clubs, lies and shot shapes) increases adaptability. Augmented feedback (video, force‑plate outputs) is most effective when systematically reduced as skill stabilises to avoid dependency. Progression from blocked to random practice should match skill level.

Q12. What role do sensory systems play in follow‑through control?

A12. Proprioception informs limb position and deceleration timing; vestibular and visual inputs support balance and orientation; haptic feedback through the grip and shaft at impact helps refine follow‑through adjustments. Integration of these modalities enables rapid online corrections and the consolidation of feedforward programs for subsequent swings.

Q13. How can technology help quantify and improve follow‑through mechanics?

A13.High‑speed video provides frame‑by‑frame kinematic analysis. IMUs give in‑field angular velocity and rotation data. Force plates record GRF timing and CoP shifts. EMG reveals muscle timing and eccentric control. Combining these data enables objective diagnoses, tailored interventions and progress monitoring.Q14. What are the main injury risks tied to poor follow‑through mechanics and how are they reduced?

A14.Common risks include lumbar strain from shear forces or abrupt deceleration,oblique and abdominal strains from insufficient eccentric control,rotator cuff overload from uncontrolled arm braking and lateral epicondylitis from repeated maladaptive wrist decelerations. Mitigation: eccentric‑focused strengthening of core and hips, improved thoracic and hip mobility, technique training for correct sequencing and deceleration, load management and graduated conditioning.

Q15. How should coaching be adapted for novice, intermediate and elite golfers?

A15. Novices: focus on balance, simple external cues and slow, high‑feedback practice. Intermediates: refine sequencing, add tempo variability and start strength/eccentric conditioning. Elite players: target marginal sequencing gains, refine deceleration strategies, integrate sport‑science monitoring (IMU, force plate) and prepare for performance under fatigue. tailor prescriptions to anthropometry, mobility, injury history and goals.

Q16.Are there trade‑offs between a textbook finish and individual effectiveness?

A16. Yes. An ideal finish is a helpful template, but anatomical and motor‑learning differences can yield option yet effective finishes. Coaches should prioritise consistent impact conditions, efficient energy transfer and injury prevention over strict aesthetic conformity, using performance metrics alongside biomechanical criteria to assess success.

Q17. What simple checks can a coach use on the range without advanced kit?

A17. Quick checkpoints:

– Can the player hold a balanced finish for 2-3 seconds?

– Is weight clearly on the lead foot after impact?

– Is the torso turned toward the target without collapsing?

– Is club path and face alignment reasonably repeatable?

– Use down‑the‑line and face‑on video to review rotation, sequencing and finish posture.

Q18. What immediate cues can correct a faulty follow‑through during a lesson?

A18. Try pauses at three‑quarters and at full finish, a step‑through to encourage weight shift, a towel‑under‑arm to keep connection, or slowed swings to feel sequencing.Provide side‑by‑side video of good and poor reps to enhance the player’s perception.

Q19. How does fatigue alter follow‑through biomechanics and practice planning?

A19. Fatigue degrades sequencing timing, reduces eccentric braking capacity, alters GRF patterns and increases compensations – raising inconsistency and injury risk. Limit high‑intensity swing volumes, schedule technique work when fresh, and include conditioning for fatigue resistance (strength endurance, aerobic work).

Q20. What concise, evidence‑based takeaways should practitioners apply?

A20.Key points:

– Regard the follow‑through as both a diagnostic of upstream mechanics and a trainable target for consistency.

– Prioritise proximal‑to‑distal sequencing, controlled eccentric braking and effective weight transfer.

– Use objective measures (video, IMU, force plates) when available; otherwise rely on balanced finish and weight‑transfer checks.

– Combine drills that train timing and deceleration (pause‑finish, med‑ball throws, step‑through) with strength and mobility work.

– Individualise coaching, focus on performance and injury prevention, and apply motor‑learning principles (external focus, variable practice, faded feedback).

If desired, options include converting these Q&As into a concise coach checklist, producing short progressive sessions targeting follow‑through, or generating sample assessment templates for video or IMU data.

The follow‑through is more than a visual closing position – it is a biomechanically informative phase that both reflects and shapes kinematic sequencing, muscular coordination and sensorimotor control behind the shot. Measurable patterns in joint trajectories, timing and EMG during the finish reveal how effectively momentum is transferred, how well deceleration is managed and whether motor programs are robust. treating the follow‑through as an integral component of the swing reframes it from a cosmetic afterthought into an actionable diagnostic and training target.

For practitioners and researchers, this approach has clear implications: coaching should emphasise movement continuity and deceleration mechanics as much as impact variables; training programmes must include drills that consolidate optimal sequencing, eccentric control and proprioceptive awareness; and assessment should use quantitative tools (high‑speed kinematics, wearable IMUs, surface EMG) to individualise feedback and track adaptation.Applying augmented feedback and progressive motor‑learning frameworks can speed transfer of desirable follow‑through characteristics into competition while preserving the variability that underpins resilient performance.

future work should further explore how body proportions, fatigue and equipment interact with follow‑through mechanics to affect dispersion and injury risk, and should evaluate the long‑term effects of targeted interventions on both performance and musculoskeletal health. By placing the follow‑through within an evidence‑based model that blends biomechanics, motor control and applied coaching, golfers and coaches can convert mechanistic knowlege into measurable gains in precision, consistency and sustainable performance.

Perfect Your Finish: The Biomechanics of a Winning Golf Follow‑Through

Pick the tone – headline variations (technical, performance‑focused, catchy)

Below are the 12 headline options you provided, each rewritten for four headline styles: blog, academic, social (short & punchy), and video (thumbnail-friendly). Pick the tone that fits your audience.

- 1. Perfect Your Finish: The Biomechanics of a Winning Golf Follow‑Through

- Blog: Perfect Your Finish: How to Build a Reliable Golf Follow‑Through (Drills Included)

- Academic: Biomechanical Determinants of an Effective Golf Follow‑Through

- Social: Nail Your finish – Hit More Greens!

- Video: Perfect Your Finish in 5 Drills

- 2. The Science of the finish: How follow‑Through Biomechanics Boosts Accuracy

- Blog: The Science of the Finish – Improve Accuracy with Better Follow‑Through

- Academic: Follow‑Through Biomechanics and Shot Dispersion: A Controlled Study

- Social: science = better Shots 🧪🏌️

- Video: The Science of the Finish – Why Pros Keep Their Finish

- 3. Finish Strong: Mastering Golf Follow‑Through Through biomechanics

- Blog: finish Strong – Biomechanics-Based Drills for a Stable Follow‑Through

- Academic: Controlled Rotational Kinematics for Finish Stability in Golf

- Social: Finish Strong. Score Lower.

- Video: Finish Strong – 7 Tips That Changed My Game

- 4. Follow‑Through Secrets: Kinematics and Muscle Coordination for Consistent Swings

- Blog: Follow‑Through Secrets That Improve Consistency

- Academic: Kinematic and Muscular Coordination Patterns Underlying Consistent Golf Swings

- Social: Secrets Pros use for Repeatable Shots

- Video: Follow‑Through Secrets – Kinematics Simplified

- 5. From Impact to Follow‑Through: The Biomechanical Blueprint for Better Golf

- Blog: From Impact to Finish – Your blueprint for better Ball Flight

- Academic: Sequential Biomechanics from Impact Through Follow‑Through in Golf

- Social: Impact → Finish = Better Golf

- Video: The Blueprint from Impact to Finish (Visualized)

- 6.Precision in the Finish: Unlocking Swing Consistency with Biomechanics

- Blog: Precision in the Finish – How Small Changes Boost Consistency

- Academic: Quantifying Finish Precision and Its Relationship to Shot Variability

- Social: Precision = Confidence

- Video: Unlock Consistency with This Finish Drill

- 7. The Anatomy of a Great Finish: Sensorimotor Tips for Golf Swing mastery

- Blog: The Anatomy of a Great Finish – Sensorimotor Cues That Work

- Academic: Sensorimotor Contributions to Finish Posture in Golf Swing Performance

- Social: Feel the Finish. Play Better.

- Video: Sensorimotor Tips for a Pro Finish

- 8. Swing Science: Optimize Your Follow‑Through for Power and Precision

- Blog: Swing Science – Balancing Power & Precision in Your Follow‑Through

- Academic: Optimizing Follow‑Through Dynamics for Combined Power and Accuracy

- Social: Power + Precision = Better scores

- Video: Swing Science – More Distance Without losing Accuracy

- 9. Finish Like a Pro: Biomechanical Strategies to Transform Your Golf Swing

- Blog: Finish Like a Pro – Strategies Backed by Biomechanics

- Academic: Professional Finish Characteristics and Transfer to Amateur Play

- Social: Finish Like a Pro. Feel the Difference.

- Video: Finish Like a Pro in 10 Minutes

- 10. Kinematics to Confidence: Engineering the Perfect golf Follow‑Through

- Blog: Kinematics to Confidence – Engineer a Finish You Trust

- Academic: Kinematic Pathways to Improved Confidence and Performance in Golf

- Social: Confidence = Better Swing

- Video: Engineer Your Perfect Follow‑Through

- 11. The Follow‑Through Factor: How Muscle Coordination Drives Swing Performance

- Blog: The Follow‑Through Factor – Coordinate Muscles, Lower Scores

- Academic: Muscle Coordination patterns as Predictors of Swing Performance

- Social: Muscle Sync = Swing Win

- Video: The Follow‑Through Factor - see the Muscle Work

- 12. Master the Finish: Evidence‑Based follow‑Through Techniques for Better Golf

- Blog: Master the Finish – Evidence-Based Techniques That Stick

- Academic: Evidence-based Interventions to Improve Follow‑Through Mechanics

- Social: Master the Finish. Master Your Game.

- Video: Master the Finish – 6 Evidence-Based Moves

Biomechanical principles that govern an effective follow‑through

kinematics: path, rotation, and extension

The follow‑through is the kinematic continuation of the impact event. Key kinematic targets:

- Rotation continuity: the hips and torso should rotate through impact toward the target, creating a balanced finish (hip-shoulder separation reverses after impact).

- Club path and face control: a repeatable post‑impact path reduces side spin and dispersion-promote a shallow, accelerating release rather than a forced flip.

- Extension and release: extension through the arms and a controlled release (unwinding of forearm supination/pronation) maintain clubhead speed while stabilizing face angle.

Muscle coordination and sequencing (proximal‑to‑distal)

Efficient swings follow a proximal‑to‑distal activation pattern: hips → torso → arms → hands → club. This sequence generates angular momentum while minimizing late compensations that create miss‑hits. Key muscles involved: gluteus maximus and medius, obliques and erector spinae, rotator cuff, forearm flexors/extensors, and intrinsic hand muscles for grip modulation.

Ground reaction forces,balance,and weight transfer

Effective follow‑through depends on how well you use the ground.A solid push of the trail leg into the ground at downswing initiation transfers energy upward and toward the target. Maintain dynamic balance by controlling center of mass over the lead foot through the finish to avoid early hanging back or collapsing.

Sensorimotor control,tempo,and deceleration

Proprioception (body‑awareness) helps you sense the correct finish without overthinking. Tempo and rhythm regulate the timing of release and deceleration; deceleration is an active process-eccentric muscle control of shoulders and forearms slows the club safely while preserving direction.

Practical drills to optimize your golf follow‑through

Use these drills to train the kinematics,sequencing,and sensorimotor skills that produce a reliable finish. warm up before intensive drills.

| Drill | purpose | How to do it |

|---|---|---|

| Slow‑motion 3‑stage swing | Train sequencing | Takeaway → transition → finish at 50% speed; repeat 10 reps |

| Pause‑at‑impact | improve impact/finish connection | Hit half shots, pause one second post‑impact, then complete finish |

| Step‑through drill | Force weight transfer & balance | Start with feet narrow, step lead foot toward target during follow‑through |

| Medicine ball rotational throws | Build hip‑to‑shoulder power | 3 sets of 6 throws (rotational, chest‑height) |

| Impact bag | Train forward shaft lean and release | Hit light blows into a padded bag focusing on acceleration through impact |

Drill details and coaching cues

- Slow‑motion 3‑stage swing – cue: “Lead with the hips, let arms follow.”

- Pause‑at‑impact – cue: “Hold your chest open and feel the weight on your lead foot.”

- Step‑through drill – cue: “finish over the front foot; don’t fall back.”

- Medicine ball throws – cue: “Explode through the ball with the hips,then let the torso follow.”

- Impact bag – cue: “accelerate, don’t decelerate early; feel the club release past the hands.”

Common follow‑through faults and speedy fixes

1. Early release / flip

Symptoms: weak ball flight, inconsistent spin, loss of distance.

- Fixes: impact bag drills, extend through impact, maintain wrist hinge longer, practice slow swings emphasizing lag.

2. Hanging back / no weight transfer

Symptoms: thin shots and poor compression.

- fixes: step‑through drill, imagine pushing trail foot into the ground, practice transfer drills without clubs.

3.Over‑rotation / loss of balance

Symptoms: pulled or blocked shots,inconsistent contact.

- Fixes: balance drills (single leg holds), reduce turn intensity in takeaway, drill 3‑stage swing to control rotation speed.

4.Open or closed finish (face alignment issues)

Symptoms: slices or hooks.

- Fixes: path & face drills (gate drills), check grip and wrist release timing, slow motion to monitor clubface through finish.

Sensorimotor & motor learning strategies

Training the nervous system to reproduce a finish reliably is as crucial as strength. Use these principles:

- External focus: cue target outcomes (e.g., “finish pointing at the flag”) rather than internal muscle cues for better automaticity.

- Variable practice: practice with slight variations (different clubs, lies, tempos) to improve adaptability.

- Blocked → random sequencing: start blocked for motor patterning, move to random to consolidate learning under pressure.

- Feedback: use video,launch monitor data,or coach feedback. Delay augmented feedback occasionally to encourage internal error detection.

How to measure progress - metrics that matter

- Shot dispersion: tighter left/right grouping indicates improved face control and follow‑through repeatability.

- Ball flight quality: consistent launch angle and spin rate mean the finish is producing the expected impact conditions.

- Postural stability: shorter sway time after the finish and the ability to hold a balanced finish shows motor control gains.

- Functional measures: medicine ball rotational power and single‑leg balance times correlate with rotational stability and balance in the finish.

Sample 6‑week practice plan (follow‑through focused)

Practice sessions should be 3-4 × per week for best retention. Each session: 10-15 min warm‑up, 30-45 min focused work, 10-15 min short game/putting.

| Week | Primary focus | Key Drills |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Sequencing & balance | Slow‑motion swings, step‑through (3×10) |

| 2 | Extension & release | Impact bag (5×8), pause‑at‑impact |

| 3 | Power transfer | Medicine ball throws, step‑through with full swings |

| 4 | Precision & face control | Gate drills, video review |

| 5 | Under pressure | Random practice + simulated course shots |

| 6 | Test & consolidate | Track dispersion on range, 9‑hole evaluation |

Case study: how follow‑through work changed a 12‑handicap’s scores

Player profile: 12‑handicap amateur with a slice and inconsistent distance. After 6 weeks focusing on follow‑through sequencing and impact drills:

- Observed changes: improved weight transfer, held finishes more consistently, less early release on irons.

- Objective metrics: average dispersion reduced by 18 yards on long irons; ball speed increased ~3 mph due to cleaner contact.

- Outcome: two‑stroke reduction in typical 9‑hole score and greater confidence hitting into greens.

Takeaway: small, targeted changes to finish mechanics-sequencing, extension, and stability-translate quickly into measurable performance improvements.

Video and content ideas to amplify this follow‑through work

- Short social clips: 15‑30s before/after finish comparisons (slow‑motion)

- Longer tutorial: breakdown of sequencing with overlay graphics showing hip/shoulder rotation

- Drill playlist: weekly drill rotation with captions and coaching cues for each step

Quick checklist for an effective follow‑through

- Weight: predominantly on lead foot at finish.

- Rotation: hips ahead of shoulders, chest open toward the target.

- Balance: able to hold finish for 2-3 seconds without wobble.

- Arms: extended but relaxed, club finishing over left shoulder (for right‑handers).

- Face: neutral to slightly closed through release (depends on desired shot shape).

Pro coaching cue: “Finish with your chest and hips pointing at the target – let your arms look after the club.” external outcomes like where your chest points are easier to control under pressure than internal muscle instructions.

Resources & tools

- Video capture (smartphone slow‑motion) – review finish from face‑on and down‑the‑line.

- Launch monitor (if available) – check side spin and dispersion changes after drill work.

- Balance pads/ single‑leg stands – train finish stability.

- medicine ball and impact bag - build power and impact feel safely.

SEO & keyword notes for publishing

- Primary keywords used: golf swing, golf follow‑through, follow‑through biomechanics, swing mechanics, golf drills, swing consistency.

- Use H1 for the main headline (as above), H2/H3 for subsections. Include target keyword in first 100 words and meta description.

- Add alt text to images like “golf follow-through biomechanics slow motion” and interlink to related posts (e.g., impact mechanics, swing sequencing).

- Include a short FAQ block on the page for “What is the proper follow‑through?” and “How long to practice?” to capture featured snippets.

If you want, I can:

- Customize any of the 12 headlines into a final H1/H2/H3 set for a blog post, academic abstract, social copy, or video thumbnail text.

- Create a 90‑second script for a video that demonstrates the top three drills.

- Generate an FAQ section optimized for featured snippets with schema markup.