Note: the supplied web search results did not pertain to golf; the following introduction is composed from general past scholarship conventions and aims relevant to the requested topic.

Introduction

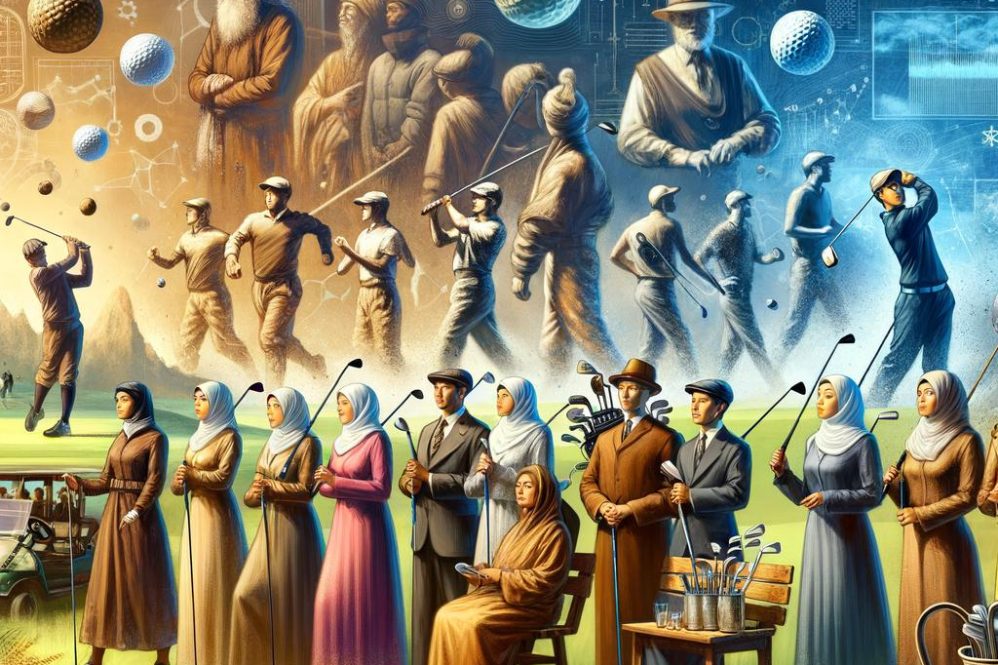

Golf occupies a distinctive place in the cultural and recreational history of the modern West, combining enduring local traditions with persistent processes of institutionalization, codification, and globalization. This article examines the historical evolution of golf from its commonly recognized origins in late medieval Scotland through its conversion into a regulated,commercialized,and internationally practiced sport. By tracing developments in rule-making, course design, and social contexts, the study situates golf both as a product of specific historical circumstances and as an agent that has shaped landscapes, leisure practices, and social hierarchies across successive eras.The narrative begins with an assessment of the evidence for early ball-and-stick games in northern Europe and concentrates on the fifteenth-century Scottish antecedents-local customs, early clubs, and proto-regulatory practices-that most clearly prefigure modern golf.Attention then shifts to the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, when technological innovations (in clubs, balls, and agronomy), the formalization of rules by bodies such as the royal and Ancient Golf Club, and the emergence of standardized competitions consolidated golf’s institutional framework. Parallel to these processes, the evolution of course design-from rudimentary linksland play to architect-designed parkland and resort courses-reconfigured relationships between players, landscapes, and commercial interests.

This study emphasizes three interrelated analytical strands. First, the development of rules and governing institutions is treated not merely as technical regulation but as a lens into changing notions of fairness, amateurism, and professionalism. Second, the morphology of golf courses is analyzed as an expression of environmental adaptation, aesthetic preference, and social access. Third, the article explores how broader societal transformations-industrialization, urbanization, shifts in class relations, imperial networks, and the rise of mass leisure-mediated golf’s diffusion and redefinition. Drawing on primary sources (club minutes,early rulebooks,course maps) and relevant secondary literature,the article offers a synthetic account that both charts continuities and interrogates contested narratives about tradition and modernization within the history of sport.

By integrating institutional,material,and social perspectives,the article aims to provide a nuanced account of how golf has evolved from a regionally rooted pastime into a globally recognized sport,while reflecting on the tensions between conservation of heritage and pressures for commercial and cultural change.

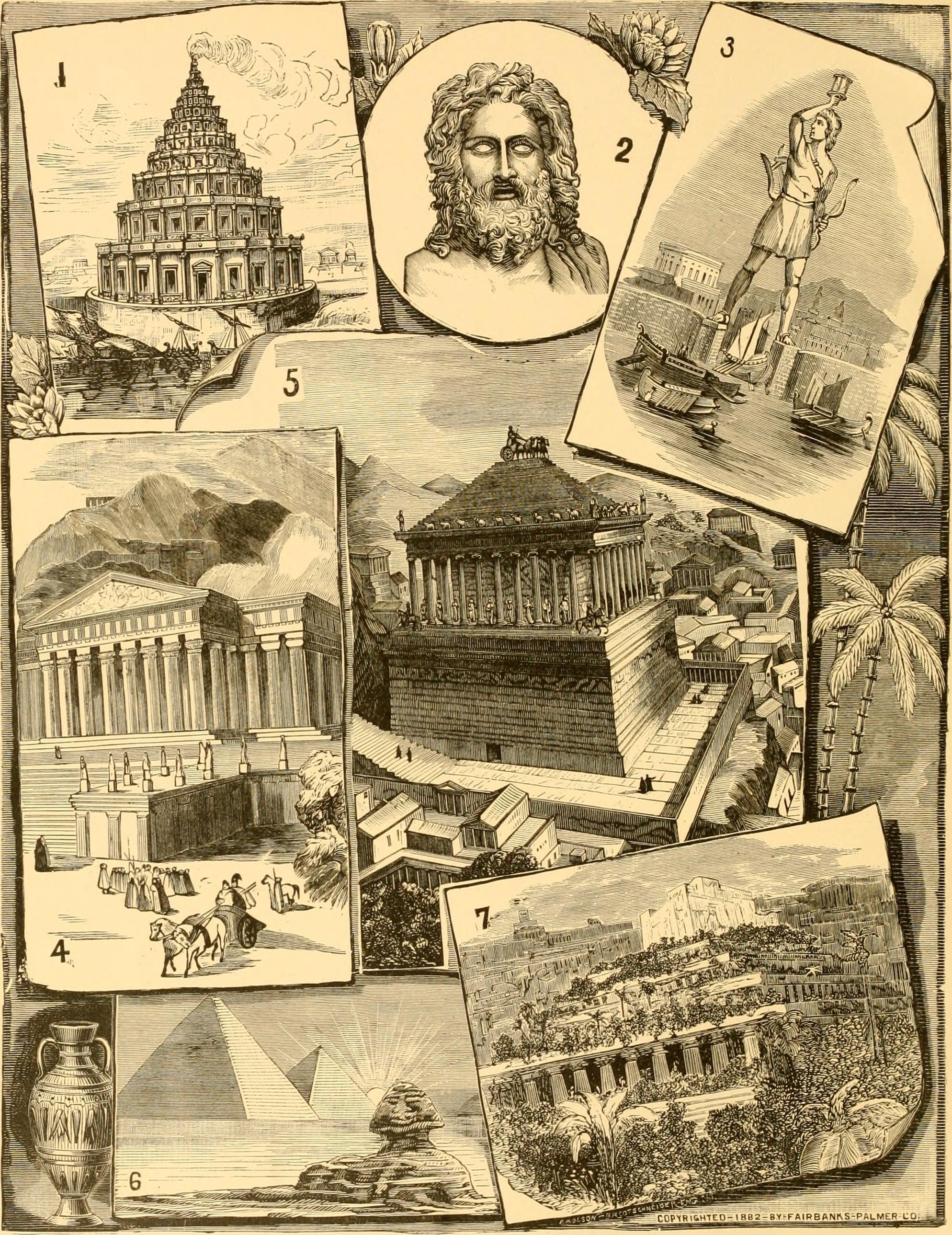

Early Origins and Cultural Precursors of Golf: Archaeological Evidence, Historical Debates, and Research Recommendations

Material traces for proto-golf activities are sparse and fragmentary: organic clubs, simple leather-covered balls and ephemeral course markers seldom survive in the archaeological record. what does persist are landscape signatures – linear fairways, coastal commons and medieval waste lands later co-opted for ball games – and occasional artefactual hints in the form of worked-wood fragments or metal ferrules plausibly associated with striking implements. Careful stratigraphic recording and targeted sampling at sites with documented historical references can convert these suggestive remains into robust evidence for early play and course use.

Comparative cultural evidence complicates singular-origin narratives. East Asian games such as chuiwan, medieval continental stick-and-ball traditions and Dutch kolf offer morphological analogues rather than direct genealogies. Linguistic and documentary data – early Scots terms,municipal ordinances,and notarial records – provide temporal anchors for when particular practices became socially salient. The balance between independent invention and cultural transmission must thus be treated as an empirical question rather than assumed in advance.

Scholarly debate has been shaped as much by national historiographies as by data. Competing claims about precedence ofen reflect modern identity construction more than archaeological certainty. methodological challenges include preservation bias, ambiguous typologies for “club” artefacts, and the retrospective projection of modern rules onto diverse past practices. The following concise matrix summarizes how evidence types map onto confidence and methodological needs:

| Evidence Type | Representative Example | Recommended Method |

|---|---|---|

| documentary | Municipal bylaws, court records | Archival prosopography, palaeography |

| Artefactual | Worked-wood ferrule | Wood species ID, AMS dating |

| Landscape | Persistent open commons | GIS, paleoenvironmental coring |

To advance understanding beyond anecdote, interdisciplinary protocols are essential. Recommended approaches include coordinated archival surveys tied to geo-referenced landscape sampling,experimental replication of putative clubs and balls to test wear patterns,and application of biomolecular techniques to identify timber species and adhesives. Equally important is reflexive historiography that documents how modern rule-sets and institutional interests have shaped interpretations of earlier play.

For immediate research priorities, scholars should pursue:

- Targeted excavations at coastal commonlands and documented early greens with integrated dating programs.

- cross-cultural comparative studies that model functional convergence versus diffusion using explicit criteria.

- Material-science analyses (e.g., isotopic and wood-anatomical) on preserved implements and ball remains.

- Landscape-scale GIS reconstructions linked to archival records to identify continuity of play areas.

- Collaborative databases that aggregate documentary, artefactual and environmental datasets for reproducible synthesis.

Institutionalization of the Game in Scotland: formation of Clubs, Local Rules, and Governance Implications

The crystallization of golf as a club‑based pastime in Scotland during the mid‑18th century transformed dispersed, informal play into an organized social practice. Small assemblies of players-often landowners, merchants and professionals-established permanent meeting places on the links and introduced regularized teeing times, membership rules and internal sanctions. The most frequently cited prototype is the Society of St Andrews Golfers (founded 1754), whose practices exemplified how local associations converted customary play into durable institutions with procedural norms and reputational authority.

Local rulemaking addressed the peculiarities of coastal links and communal land tenure, producing a repertoire of pragmatic regulations that varied from one course to another. Clubs developed conventions to adjudicate uncertain situations and to limit disputes,such as:

- Teeing order: formalizing the sequence of play to reduce conflicts and preserve pace.

- Hazard definitions: distinguishing natural obstacles, bunkers and out‑of‑bounds in site‑specific terms.

- Lost ball and time limits: specifying how long a ball could be sought before being declared lost.

- Local courtesy codes: informal sanctions addressing etiquette, dress and behavior on the links.

These municipalized rules produced substantive governance implications. Clubs functioned as private regulators, exercising adjudicative authority over members and acting as custodians of land and customary practices. membership criteria and disciplinary mechanisms reproduced social hierarchies-restricting access by class, gender and occupation-and thereby embedded exclusionary logics within the sport’s early institutional architecture. Simultaneously occurring, club governance fostered a culture of arbitration and precedent that facilitated consistent decision‑making across disputes.

As play expanded beyond local contexts, the patchwork of club rules precipitated pressures for harmonization. By the late nineteenth century, representative bodies emerged to mediate between local custom and broader sport‑wide uniformity: national associations consolidated rulebooks, standardized equipment definitions, and negotiated inter‑club competitions.

| Organization | Primary governance role |

|---|---|

| National associations | Codify rules and coordinate championships |

| Clubs | Local adjudication and land stewardship |

This institutional layering enabled match play and stroke play to be compared across regions, facilitating the sport’s transition to an international pastime.

Contemporary governance still bears the imprint of these origins: enduring club customs inform course maintenance, amateur codes and ceremonial rites, even as rule committees confront modern challenges-technology, inclusivity reforms and environmental stewardship. Major rule revisions (such as the comprehensive changes implemented in 2019) illustrate how historic precedents are reinterpreted within centralized regulatory frameworks. Academically, the story is instructive: early institutionalization created both the procedural foundations necessary for global standardization and the social constraints whose reform continues to animate debates about equity and the public purpose of golf.

Standardization of the 18 hole Format and Course Architecture: Design Evolution, Turf Management Innovations, and Preservation Best Practices

By the mid‑19th century a convergence of play practice, club management and influential precedents produced a de facto uniformity in round length that would become canonical. The reduction and consolidation of linksland layouts-most famously at St Andrews where earlier multi‑green sequences were rationalized-combined with the Royal and ancient Golf Club’s rising regulatory authority to entrench the 18‑hole round as the international standard. This codification was not merely numeric: it reflected an emerging philosophy that balanced endurance, variety and competitive integrity, thereby aligning course construction, tournament scheduling and equipment evolution within a single, reproducible framework.

Architectural thinking evolved in parallel from opportunistic routing on coastal links to considered, purpose‑driven design across varied landscapes.Pioneers such as Old Tom Morris, Alister MacKenzie and Donald ross introduced principles of **strategic risk‑reward**, visual deception and green complexity that persist in contemporary practice.Designers moved from merely occupying terrain to sculpting it-employing routing,tee hierarchy,cross‑bunkering and contoured greens to create sequences of holes that test shot‑making,decision‑making and course management rather than raw length alone.

Turf science and maintenance technologies redefined playable surfaces and seasonal reliability. The transition from native roughs to sown turf complexes was accelerated by innovations in **irrigation, drainage, mechanized mowing and turfgrass breeding**. The introduction of species such as creeping bentgrass and improved strains of bermudagrass, combined with refined fertilization regimes and integrated pest management, delivered faster putting surfaces and more consistent fairways while enabling year‑round calendaring of events. Equally important were subsurface improvements-sand cap construction and slit‑drain systems-that transformed previously marginal soils into championship venues.

Preservation and stewardship now occupy the same centrality as playability in contemporary course management. Best practices emphasize ecological integrity, resource efficiency and cultural conservation:

- Water stewardship: precision irrigation, drought‑tolerant species and reclaimed water use.

- Habitat conservation: native buffers, wetland protection and wildlife corridors.

- Soil health: organic matter management, aeration programs and reduced chemical reliance.

- Cultural preservation: protecting historic routing, sightlines and original green complexes.

- Community integration: shared access, multi‑use corridors and educational outreach.

These measures reconcile the sporting, environmental and social imperatives of modern golf while safeguarding legacy landscapes for future generations.

Contemporary resilience is best expressed as a practical synthesis: retain the strategic vocabulary of historic designs while adopting adaptive agronomy and manufacturing innovations that reduce ecological footprint. the following succinct matrix captures core design considerations and their primary benefits in modern stewardship:

| Design Consideration | Primary Benefit |

|---|---|

| Strategic Routing | Varied play and preserved sightlines |

| native Vegetation | Reduced inputs, improved biodiversity |

| Sand Cap & Drainage | All‑season playability |

| Water‑Efficient Irrigation | Lower consumption, cost savings |

In affect, stewardship‑minded architecture marries respect for tradition with pragmatic innovation, ensuring that the sport’s physical and cultural artifacts endure in a changing climate and social landscape.

Technological Advancements and Equipment Regulation: From Hickory Shafts to Modern Materials and Policy Recommendations for Competitive Integrity

Technological trajectories in club and ball construction have transformed the sport from artisanal craft to high‑precision engineering. Early hickory‑shafted clubs, characterized by variability in flex and weight, gave way to steel shafts in the 1920s and later to graphite and multi‑material composites that permit unprecedented control of moment of inertia, center of gravity, and vibration damping.These material shifts not only altered striking dynamics but also the very metrics by which performance is assessed-ball speed, launch angle, spin rates and dispersion patterns-requiring a recalibration of coaching, course architecture and competitive standards. The cumulative effect is that equipment is now as determinative of outcomes as technical skill, a fact that informs regulatory priorities.

Regulatory institutions have periodically intervened to preserve the game’s intended challenge and fairness, establishing conformity protocols and banned innovations when necessary. A concise chronology encapsulates key inflection points and responses:

| Era | Technological Change | Regulatory response |

|---|---|---|

| Late 19th-early 20th c. | Hickory shafts, handmade balls | Informal norms; club standardization begins |

| 1920s-1970s | Steel shafts, persimmon woods | Formal testing protocols introduced |

| 1980s-2000s | Graphite, titanium, larger clubheads | Conformity limits; groove and COR rules |

| 2010s-present | Advanced composites, engineered balls | Enhanced lab testing and policy collaboration |

Policy interventions must be evidence‑based, clear and adaptive to reconcile innovation with equity. Recommended measures include the following best practices, designed to sustain competitive integrity while allowing responsible technological progress: independent third‑party conformity testing, standardized performance caps expressed in measurable units (e.g., ball speed ceilings), and phased implementation timelines allowing players and course managers to adapt. Additional recommendations emphasise stakeholder inclusion-manufacturers, players, course designers and governing bodies should participate in periodic reviews to balance commercial incentives with the public interest.

Empirical oversight is essential for credible enforcement. Modern measurement tools-high‑resolution launch monitors, standardized test rigs and material audits-enable regulators to quantify advantage and craft proportionate rules. Institutional adoption of accredited laboratories, mandatory serial testing of production batches and publicly accessible conformity databases would reduce ambiguity and litigation.governance should explicitly incorporate sustainability metrics (material lifecycle and recyclability) and access considerations so that technological advancement broadens, rather than narrows, participation in the sport.

Social and Economic Dimensions of Golf’s Expansion: Class, gender, and Globalization with Strategies for Inclusive Development

Across the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, golf developed as a pronounced marker of social distinction, its landscapes and institutions often reinforcing pre-existing patterns of wealth and power. Landownership, membership fees, and the concentrated geography of courses produced a durable form of **class stratification**: clubs acted not merely as sporting venues but as sites of social reproduction where networks, capital accumulation, and cultural capital were consolidated.Scholarly analyses underscore that the material costs of equipment and course maintenance, alongside exclusive governance structures, translated into persistent socio-economic barriers that limited broader participation.

Parallel to class dynamics, gender shaped both access and the normative culture of the game. For much of golf’s history, women were relegated to separate tees, auxiliary competitions, or secondary membership statuses, reflecting broader patterns of **gendered spaces** in sport.The gradual enfranchisement of women-through the formation of women’s clubs,professional circuits,and policy interventions-illustrates the interplay between social movements and institutional change.Yet contemporary disparities in prize money, media coverage, and leadership representation reveal that formal inclusion has frequently enough outpaced structural equality.

The globalization of golf reconfigured these social and economic contours by embedding the sport within transnational flows of capital,media,and tourism. From imperial diffusion to modern broadcast networks and multinational sponsorships, golf became both a vehicle of soft power and a commodity shaped by global circuits of production and consumption. The emergence of new markets in East Asia, the Middle East, and Latin America demonstrates how course design, tournament organization, and commercial branding adapt to regional socio-economic contexts while perpetuating certain neoliberal imperatives-notably privatization and elite consumerism.

Addressing entrenched inequities requires targeted, evidence-based strategies that combine policy, community partnership, and institutional reform. Effective interventions emphasize affordability, spatial redistribution, and representational equity. Practical measures include:

- Public investment in municipal and school-linked courses to lower entry costs;

- Inclusive governance that reserves leadership seats for underrepresented groups;

- pathways for talent such as scholarships, coaching programs, and feeder tournaments;

- Design innovations that create multi-use, accessible facilities accommodating diverse users;

- Partnerships with community organizations to tailor programming to local needs.

economic instruments to monitor and promote inclusive development must be clear and measurable. The table below offers a concise typology linking common barriers to pragmatic interventions, suitable for policy planners and club administrators seeking targeted reforms.

| Barrier | strategic Intervention |

|---|---|

| High cost of entry | Subsidized equipment loans and tiered membership |

| Limited local access | Municipal courses and school partnerships |

| Underrepresentation in leadership | Quotas, mentorship, and transparent hiring |

The Role of Major Championships and Media in Shaping Modern Golf: Commercialization Dynamics and Strategic Recommendations for Sustainable Growth

Major championships and mass media have acted as twin vectors in the transformation of golf from a localized pastime into a globally commercialized sport. Through sustained coverage of flagship events, broadcasters and digital platforms have standardized narratives about competitive excellence, institutional legitimacy, and player celebrity. This process produced a feedback loop: compelling media presentation increased audience demand, which in turn elevated the commercial value of tournaments and the governing bodies that host them. The result is a modern landscape in which prestige and profitability are tightly interwoven, and where **institutional reputation serves as a principal economic asset**.

Commercialization dynamics manifest across several interdependent channels: broadcast rights, sponsorship architecture, prize‑fund escalation, and ancillary hospitality revenues. Each channel exerts distinct pressures on organizational decision‑making, from scheduling and course setup to the prioritization of marquee players. Key mechanisms include:

Commercial mechanisms and consequences:

- Broadcast monetization: rights aggregation concentrates negotiating power with a handful of global networks.

- Sponsorship layering: cumulative brand partnerships shift tournament identities toward corporate narratives.

- Prize inflation: escalated purses incentivize player mobility and calendar concentration.

These mechanisms have increased financial resilience but also produced vulnerabilities, including dependence on cyclic advertising markets and susceptibility to short‑term rating fluctuations.

Media imperatives have reshaped competitive form and stakeholder behavior. Television-amiable tee times, highlight‑driven coverage, and advanced analytics have altered how tournaments are packaged and how players cultivate public personas. Social media amplifies individual narratives and democratizes access to content,but also accelerates attention cycles and heightens reputational risk. From a governance perspective, this environment demands robust media strategies that reconcile commercial aims with the sport’s historical ethos; failing to do so risks alienating traditional constituencies while generating ephemeral ratings gains.

For sustainable growth,strategic recommendations must balance commercialization with long‑term stewardship. Priority actions include institutionalizing transparent revenue‑sharing, investing in grassroots participation, adopting environmental best practices for venue management, and diversifying media partnerships to include public-interest programming. The table below summarizes concise policy levers and expected outcomes.

| Policy Lever | Short‑Term Effect | Long‑Term outcome |

|---|---|---|

| Revenue‑sharing model | Improved stakeholder buy‑in | Equitable ecosystem growth |

| Community investment | Increased participation rates | Deeper talent pipeline |

| Media diversification | Broader audience reach | Resilience to market shocks |

Implementation must be iterative and evidence‑based, guided by independent evaluation metrics that track social, fiscal, and environmental indicators alongside traditional commercial KPIs.

environmental Challenges and Sustainable Course Management: Ecological Impacts, Regulatory Frameworks, and Operational Recommendations

Golf landscapes exert measurable effects across terrestrial and aquatic ecosystems, demanding rigorous attention to their cumulative footprint. primary ecological impacts include altered hydrology from irrigation demands, eutrophication and chemical loading of adjacent waterways due to nutrient and pesticide runoff, fragmentation of native habitats, and reduced urban biodiversity where manicured turf replaces indigenous plant communities. These pressures are spatially and temporally heterogeneous-coastal, wetland-adjacent and arid-region courses each present distinct vulnerability profiles-requiring site-specific assessment rather than one-size-fits-all prescriptions.

Effective governance is a multilayered construct that combines federal statutes, agency rules, and state-level implementation. At the federal level, statutes administered or informed by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) establish the baseline for water quality, pesticide registration and air emissions; state agencies then translate these into local permitting and compliance regimes (for example, EPA regional resources and state EPA offices such as Minnesota’s provide localized guidance). Key components of the regulatory environment typically include:

- Water quality and discharge controls (e.g., stormwater permitting, nutrient limits)

- Pesticide and fertilizer regulation (labeling, application standards, buffer requirements)

- Wetland/shoreline protection and habitat conservation (permitting for alteration or mitigation)

To reconcile playability with ecosystem stewardship, courses should integrate science-based operating practices. Core strategies emphasize reduction and substitution, habitat restoration, and technological efficiency: integrated pest management (monitoring threshold-based treatments), conversion to native-plant roughs and pollinator habitats, use of precision irrigation and moisture-sensing controllers, and creation of vegetated buffers to trap sediments and nutrients. Adoption of these measures reduces chemical inputs and water demand while often improving resilience to climate variability and regulatory constraints.

Robust monitoring and adaptive management underpin long-term sustainability. Regular measurement of indicators enables early detection of environmental stress and demonstrates regulatory compliance. A concise monitoring matrix might include:

| Indicator | Frequency | Operational Target |

|---|---|---|

| Surface water turbidity & nutrient load | Quarterly | ↓ year-over-year; meet permit limits |

| soil moisture & salinity | Biweekly (growing season) | Optimal root-zone range for turf species |

| IPM treatment frequency | Monthly review | Treat only above thresholds |

operationalizing sustainability requires corporate leadership, staff capacity-building and proactive stakeholder engagement. Practical operational recommendations include pursuing site-specific nutrient management plans, documenting pesticide decisions against IPM protocols, leveraging EPA and state agency guidance for permitting and best practices, and seeking financial or technical assistance where available. Additional recommended actions:

- Implement staff training programs on low-impact maintenance techniques

- Establish community-facing openness (annual environmental performance reports)

- engage with regulators early to streamline permitting and access incentive programs

These measures not only reduce ecological risk and regulatory exposure but also enhance social license and long-term economic viability of golf facilities.

Future Trajectories for the Sport: Emerging Technologies, Governance Reforms, and Policy Recommendations for Accessibility and Integrity

Rapid technological innovation promises to reconfigure both performance and participation in the sport. Advances such as machine‑learning swing analytics, high‑resolution launch monitors, real‑time biomechanical wearables, and augmented‑reality coaching overlays will enable individualized improvement pathways previously reserved for elite cohorts. concurrently,agritech breakthroughs-precision irrigation,drought‑tolerant turf varieties,and low‑chemical integrated pest management-will reshape course maintenance,reducing environmental footprint while preserving playability. The scholarly implication is clear: future research must evaluate not only efficacy but also equity of access to these tools across diverse socioeconomic and geographic contexts.

Reforms in governance are required to steward technological adoption and protect the sport’s integrity. International federations, tournament promoters, and national associations should pursue harmonized regulations on data ownership, device permissibility in competition, and transparent anti‑corruption protocols. Equally important are governance innovations around scheduling and resource allocation to prevent competitive imbalances that arise from unequal access to technology. Formalizing stakeholder representation-including amateur clubs, public facilities, and player associations-will promote legitimacy and adaptive rulemaking.

Policy prescriptions to increase accessibility and bolster integrity must be both pragmatic and evidence‑based. Key recommended actions include:

- Public investment in municipal and school golf facilities to broaden participation;

- Open‑access coaching platforms leveraging low‑cost digital content for skill development;

- Data governance frameworks that ensure athlete and consumer privacy while enabling research;

- Subsidy programs for community clubs to acquire sustainable agritech and basic analytics tools;

- Standardized handicapping and eligibility reforms to preserve competitive fairness amid technological heterogeneity.

These measures should be piloted, evaluated, and scaled according to measurable inclusion and integrity outcomes.

To clarify priorities for practitioners and policymakers,the following concise matrix outlines emergent domains and corresponding institutional responses:

| Domain | Priority Reform | Metric |

|---|---|---|

| Wearable analytics | Device certification & data standards | Proportion certified devices |

| Course sustainability | Incentives for low‑impact turf | Water/chemical use reduction |

| Access & development | Public funding for youth programs | Youth participation rates |

Effective implementation will require iterative evaluation,cross‑sector partnerships,and adaptive governance. Research institutions should collaborate with governing bodies to produce longitudinal evidence on technological impacts, while regulators must establish sunset clauses and review timelines to prevent ossification. Above all, preserving the sport’s cultural and ethical foundations demands that innovation serve the twin goals of widening participation and safeguarding fair competition; policies that operationalize these principles will determine whether golf’s next century is both more inclusive and more credible.

Q&A

Note on sources: the supplied web search results pertain to the Office of the Historian and related archival programs and do not provide material on golf. the Q&A below is an academically styled synthesis based on established scholarship and primary-source traditions in golf history (club records, early rule books, archival newspapers, material culture and governing-body publications). For citation-grade research, consult primary collections (club minutes, early rule codices), the R&A and USGA archives, national golf museums, and peer-reviewed sport-history journals.

Q1. What is the central argument or thesis of an article titled “The Historical Evolution of Golf: Origins to Modernity”?

A1. The article argues that golf’s contemporary form is the product of a longue durée development in which localized ball-and-stick games were transformed through institutional codification, technological innovation, and social change. it shows how rules, course design, equipment, and governance co-evolved with broader economic, imperial and cultural forces to produce a global sport that retains distinctive traditions while continuously negotiating modernization.Q2. What are the earliest origins of golf, and how do historians establish them?

A2. Historians trace golf’s proximate origins to late-medieval Scotland, where documentary references and club records from the 15th and 16th centuries indicate organized play on linksland. Earlier and geographically dispersed stick-and-ball games (e.g., Roman, Chinese, Dutch variants) provide comparative context but are not direct genealogical lines. Establishing origins relies on primary documentary evidence (royal edicts, parish records, club minutes), material culture (early clubs/balls), and landscape archaeology of play sites.Q3. How did the rules of golf develop from informal customs to standardized codes?

A3. Initially, play was governed by local customs and agreements among players. The first extant written rules appear in the mid-18th century as gentleman-club codes that formalized basic practices (order of play, hazards, voiding of poor shots). During the 19th century,proliferating clubs and inter-club competition drove the need for more widely accepted regulation. National and international authorities-most prominently British and American bodies-emerged and progressively codified rules, eventually collaborating to issue unified editions that respond to technological and competitive change.

Q4. In what ways did course design evolve, and which factors drove that evolution?

A4. Course design evolved from natural coastal “links” terrain-minimal alteration, strategic use of winds and dunes-to deliberate manipulation of inland landscapes (parkland courses) with engineered hazards, graded greens and shaped bunkers. Drivers of change included increased leisure time, club membership growth, advances in earth-moving technology, irrigation and turf science, and the professionalization of golf architecture.Designers combined strategic principles with aesthetic and environmental concerns, producing signature styles across eras.

Q5. How has equipment technology shaped play and governance?

A5. Equipment evolution-shaft materials, clubhead construction, and ball composition-has altered distance, control and shot-making. Transitions from wooden clubs and feather-stuffed balls to gutta-percha, rubber-core, and then multi-component modern balls, and from hickory to steel to composite shafts, incrementally increased performance. Governing bodies have repeatedly responded with regulations (on club and ball specifications, groove design, anchoring, etc.) to preserve competitive balance and the integrity of established course designs.

Q6. What social and cultural forces influenced golf’s expansion and democratization?

A6. golf’s spread was shaped by class, empire, industrialization and transport. Initially a pastime of elites, the sport expanded as railways, urbanization and growing middle-class leisure enabled broader participation. The 20th century saw further democratization through public municipal courses,subsidized wartime and postwar programs,and the professionalization of instruction and competition. Concurrently, persistent exclusions-by gender, race and class-were challenged across the 20th and 21st centuries, producing gradual institutional reforms.

Q7. How did governance institutions form and what roles do thay play?

A7. Local clubs first regulated play; national bodies later emerged to arbitrate inter-club competition and standardize rules. By the late 19th and early 20th centuries, national associations and international partnerships became central to rule-making, course rating, handicapping, competition organization and equipment standards. These institutions mediate tensions between tradition and innovation and serve as repositories of historical practice and policy.

Q8. What were the major moments of professionalization and commercialization in golf history?

A8. Key moments include the late-19th-century emergence of professional clubmakers and players, organized championships and the founding of professional associations; the 20th-century rise of commercial tournaments, sponsorship, broadcast media and international tours; and late-20th/early-21st-century globalization with multi-national circuits and major corporate sponsorships. Media and prize-money growth transformed professional golf into a major commercial sport.

Q9. How have gender and race shaped the sport’s historical trajectory?

A9. Gender and race have been structuring factors: women’s golf developed its own clubs and competitions but faced cultural and institutional barriers; professional women’s tours emerged to contest marginalization. Racial exclusion was formal and informal in many contexts, with policies and practices limiting access to clubs, competition and economic prospect. over time legal challenges,civil-rights activism and policy reforms (both within and outside golf institutions) have produced greater inclusion,though disparities persist.

Q10. How have major rules changes responded to technological innovation?

A10. Notable responses include equipment specification rules, limits or clarifications on club features, groove regulations, and the prohibition of anchored putting strokes. these changes aim to manage equipment-driven advantages that could undermine course design, competitive equity or the sport’s historical character. Governing bodies typically consult scientific testing, stakeholder groups and historical precedent when implementing such rules.

Q11. In what ways has course architecture reflected cultural values?

A11. Course architecture embodies cultural aesthetics, notions of gentlemanly competition, and attitudes to landscape. Early links emphasized naturalism and navigation; later parkland and “strategic” designs emphasized planned challenge and visual composition. Design trends mirror broader cultural values: conservationist sensibilities produce environmentally sensitive design; spectacle-oriented eras favor highly sculpted, tournament-ready venues.Q12. What are the principal primary sources and methodologies for researching golf history?

A12. Primary sources include club minutes, early rulebooks, tournament records, equipment catalogs, patent filings, newspapers, photographs, oral histories, and landscape/archaeological evidence. Methodologies combine archival research, material culture analysis, landscape archaeology, oral history, and critical reading of media representations. Comparative approaches situate golf within broader histories of leisure, empire, technology and social change.

Q13. How has globalization altered the sport’s structures and meanings?

A13. Globalization expanded participation, diversified competitive fields, and relocated centers of economic and athletic influence. International tours, multinational sponsorship, global broadcasting and players from diverse nations have transformed golf into a transnational spectacle. At the same time, global diffusion has produced contested meanings around tradition, local identity and commercial imperatives.Q14. What contemporary challenges and future directions does the sport face?

A14. major contemporary issues include: environmental sustainability (water use, habitat impacts), climate change effects on playable seasons and course viability, maintaining pace-of-play and grassroots participation, technological arms races, and continuing efforts to broaden inclusivity. Future directions likely emphasize sustainable course management, data-driven training and rule-making, and institutional initiatives to increase access and equity.

Q15.What are promising avenues for further academic research?

A15. productive research agendas include: microhistories of individual clubs and communities; transnational studies of golf and empire; material-culture studies of equipment production and consumption; gendered and racialized histories of access and exclusion; environmental histories of courses; and policy histories of rule-making in response to technology. Interdisciplinary work combining archival sources with landscape analysis and oral history will yield particularly rich insights.

Suggested archival and institutional starting points (for scholars)

– Club archives and early rule codices (e.g., eighteenth- and nineteenth-century club minutes)

– National governing bodies’ archives and museums (e.g., national golf museums, R&A, USGA)

– Contemporary tournament archives and broadcast repositories

– Local and national newspapers for match reports and cultural discourse

– Patent, manufacturing and trade records for equipment history

If you would like, I can:

– Convert this Q&A into a shorter FAQ suitable for publication,

– Provide a bibliography of secondary literature and primary-source repositories,

– Draft annotated questions for archival research tailored to a particular region or period.

Closing Remarks

In tracing the historical evolution of golf from its putative fifteenth‑century origins in Scotland to its contemporary globalized forms, this study has sought to foreground the interplay between institutional regulation, material practice, and social context. Attention to the codification of rules, the morphological transformations of course design, and the sport’s shifting social constituencies demonstrates that golf’s continuity of tradition has always been mediated by processes of negotiation-technical, cultural, and economic-rather than by simple preservation.

This account underscores two central arguments. First, the formalization of rules and the standardization of equipment and play reflect broader modernizing tendencies in sport and governance, producing both inclusions (broader competitive structures, international bodies) and exclusions (class-, gender-, and race-based barriers) whose legacies persist. Second, changes in course design and landscape management reveal golf as a site in which aesthetic, environmental, and commercial imperatives converge, making the sport a useful lens for examining human-environment relations and the commodification of leisure.

methodologically, this inquiry has combined archival, architectural, and socio‑cultural perspectives to capture golf’s plural histories; yet important empirical and interpretive work remains. Future research would benefit from comparative studies that situate local and indigenous forms of stick-and-ball games alongside the codified sport, from environmental histories that quantify long‑term landscape impacts, and from critical work on globalization that attends to governance, media, and economic flows.

In closing, the history of golf demonstrates how a seemingly insular pastime can reflect and refract major historical processes-modernization, imperial and commercial expansion, and social reform-while retaining distinctive traditions and practices. By continuing to interrogate its archives, material culture, and social practices, scholars can further illuminate how sport both shapes and is shaped by the wider currents of modern history.

The Historical Evolution of golf: Origins to Modernity

Early Origins and Ancestors of the Game

The exact origins of golf are a tapestry of regional stick-and-ball games spanning centuries.Early games resembling golf-played with a ball and a stick-are recorded across the world. While medieval Scotland is most often credited with shaping modern golf, similar leisure sports existed in China (chuiwan), the Netherlands (kolf), and various European traditions (jeu de mail).

Key early developments

- Medieval stick-and-ball games provide a family of antecedents to golf.

- By the 15th century, references in Scottish records and bans on play in favor of military training suggest a growing pastime that resembled golf.

- The first formalized rules and organized play emerge in 18th-century Scotland-setting the stage for the sport we now call golf.

From Local Pastimes to Organized Sport: Rules, Clubs, and the 18-Hole Standard

Golf’s change from informal leisure to organized sport hinges on three interrelated developments: codified rules, established clubs, and course standardization.

Rules and early governance

The evolution of golf rules began with local codes set by clubs and societies of players. One of the earliest known documented sets of rules comes from a Scottish golfers’ club in the mid-18th century-these early laws covered basic play, scoring, and fair conduct. Over time, formal governing bodies emerged to create consistent, national and eventually global rules for competition.

The 18-hole course becomes standard

Originally, many courses where variable in length and number of holes. the iconic Old Course at St Andrews famously standardized the 18-hole layout when existing routing and green configurations were consolidated into an 18-hole round. That practice spread and the 18-hole round became the global norm for a standard golf round.

Major Governing Bodies and the Birth of Competitive Golf

The formal association of golf accelerated in the 19th and early 20th centuries through the establishment of governing bodies and major championships.

- Club evolution: Local clubs transformed into national and international institutions, providing rules and stewardship of traditions and courses.

- Governing bodies: National associations formed to standardize play, handicap systems, and tournament rules. Over the 20th century, major bodies collaborated to publish unified editions of the Rules of Golf.

- Major competitions: Historic tournaments grew into the professional circuits and the modern major championships that shape professional golf.

Course Design and Architecture: From Links to Modern Layouts

Golf course design is a core ingredient in the sport’s cultural evolution. Early courses were seaside links-windy,sandy,and natural.As golf spread inland, designers adapted layouts to local terrain and invented architectural features that tested strategy, shot-making, and course management.

Styles and famous design movements

- Links golf: Natural,sea-facing courses with firm turf and strategic bunkers.

- Parkland design: Tree-lined, manicured inland courses with contouring and bunkering.

- Golden-age architects: Designers refined bunker placement, greens design, and strategic routing-creating enduring templates for modern golf architecture.

Equipment Evolution: Balls,Clubs,Shafts,and Distance

one of the most visible changes in golf’s history is equipment evolution. Advances in the golf ball and golf clubs profoundly influenced how golf is played, course lengths, and strategy.

Golf balls

- Featherie (feather-stuffed) balls were handcrafted and predominated until the 19th century.

- The guttie (gutta-percha) ball, introduced in the mid-19th century, was cheaper and more durable-helping the game spread.

- The Haskell rubber-core ball (late 19th century) and later dimpled designs increased distance and altered play.

Golf clubs and shafts

- Early clubs were wooden-headed and fitted to hickory shafts for feel and versatility.

- In the early 20th century, metal shafts (steel) became more common, offering consistency and durability.

- Graphite and composite materials arrived in the late 20th century, enabling lighter, faster club heads and new engineering in driver design.

Competition, Media, and the Professional Game

The rise of professional golf and broadcast media changed golf’s social and economic landscape. Televised tournaments introduced golf to global audiences, sponsorship and prize money increased dramatically, and player celebrity turned top professionals into household names-fueling participation growth and commercial investment in courses, academies, and technology.

How tournaments shaped modern golf

- Major championships and national opens established traditions and historical legacies.

- Professional tours standardized competitive formats and year-round scheduling.

- Television & digital media drove sponsorship, analytics, and a new era of golf instruction and fan engagement.

etiquette and the Social Culture of Golf

Golf’s etiquette-respect for fellow players, care for the course, and self-regulation-has been a defining feature of the game as its formative years. Core customs that endure include:

- Repairing divots and ball marks

- Raking bunkers and replacing the rake

- Maintaining silence and attention while a player is preparing a shot

- Calling “fore” as a safety warning

- Observing pace of play

Technology, Analytics, and the Data-Driven Modern game

Modern golf is increasingly shaped by technology: launch monitors, swing analyzers, GPS and rangefinder tech, and advanced club manufacturing. Data-driven instruction has become mainstream-players at all levels use video analysis, biomechanics, and statistical tracking to optimize the golf swing, short game, and course strategy.

Practical tips to use technology wisely

- Use launch monitors for objective feedback-focus on repeatable swing metrics rather than raw numbers.

- Balance tech with feel; overreliance can disrupt natural tempo and creativity.

- Adopt GPS or course apps to improve course management and pace of play.

Timeline: Milestones in the Historical Evolution of Golf

| Period / Year | Milestone | Impact |

|---|---|---|

| 15th-16th century | Early references in Scotland | Emergence of golf-like play; local popularity grows |

| Mid-18th century | first written club rules | Codification begins; organized play |

| 1764 | St Andrews routing becomes 18 holes | Standard round length established |

| Mid-late 19th century | Guttie and rubber-core balls | Greater distance,affordability |

| Late 19th – early 20th century | National bodies & majors formed | Formal competitions and governance |

| 20th century | Steel & later graphite shafts; broadcast TV | Performance gains; global audience growth |

Case Study: How the 18-Hole Round Became worldwide

The path from variable course lengths to the universal 18-hole round is a great example of cultural standardization in golf. St Andrews’ practical consolidation of holes demonstrated how an established club could set a pattern other facilities adopted. As tournaments and national bodies required standardization for fair competition, the 18-hole round became the accepted benchmark-affecting course construction, tournament scheduling, and scoring records.

Benefits and Practical Tips for Players Embracing Golf’s Tradition

- Learn the rules and etiquette: Familiarity with golf rules and course manners enhances enjoyment and respect on the course.

- Study historical courses: Playing classic links or golden-age designs can deepen strategic understanding and appreciation for course architecture.

- Integrate technology selectively: Use data to support skill development but protect the feel and rhythm essential to the golf swing.

- Respect pace of play: Preserving the game’s social flow makes golf more enjoyable for everyone.

Firsthand Experience: Adapting to Course and Equipment Changes

Players transitioning from older equipment to modern clubs often report greater distance but must re-learn trajectory control and course management. A practical approach:

- Get a fitting session for driver and irons-modern clubs respond differently than vintage gear.

- Practice shots at varying trajectories to understand how new balls and clubs alter flight and spin.

- Adjust course strategy: longer clubs can shorten holes but also create diffrent bunker and hazard considerations.

SEO and Content Tips: How to Write About Golf History for the Web

- Use primary keywords naturally: “golf history”, “origins of golf”, “18-hole”, “golf rules”, “golf equipment”, “golf course design”.

- Structure content with clear H2/H3 headings and short paragraphs for readability.

- Include a concise meta title and meta description (seen above) to enhance search engine snippets.

- Use lists and tables to break up long text and improve on-page time and user engagement.

- Link to authoritative sources (golf governing bodies, historical archives, or reputable golf history sites) when publishing online to increase trust and SEO value.

Note: This article synthesizes widely documented milestones and trends in golf history-combining heritage,equipment evolution,course architecture,and governance to show how golf evolved from local pastime to global sport.