Novice golfers commonly exhibit a small set of recurring technical and tactical deficiencies that constrain shot consistency,increase injury risk,and slow skill acquisition. The word “top” is employed here in the sense of ”most prevalent” or “most consequential” (see Collins; Dictionary.com; Vocabulary.com) to denote the errors that most frequently limit early-stage performance. By focusing on a defined subset of faults-grip,stance,alignment,posture,swing path,tempo,ball position,and short-game technique-this review targets areas were relatively modest,evidence-based adjustments can yield disproportionately large gains.

Drawing on biomechanics, motor-learning theory, and empirical coaching studies, the analysis synthesizes diagnostic indicators and corrective strategies that are both safe and practicable for instructors and self-directed learners. For each error category the review summarizes underlying causes, presents objective markers for diagnosis, and recommends interventions supported by research (e.g., augmented feedback protocols, simplified practice schedules, constraint-led drill design, and progressive strength-mobility exercises). Emphasis is placed on translating laboratory findings into field-ready cues and drills, and on balancing immediate performance improvement with durable skill retention.

The goal is to provide a concise, actionable framework that facilitates rapid assessment and targeted remediation of the eight identified faults. Readers can expect a combination of concise evidence summaries, prioritized corrective protocols, and suggested practice progressions designed to accelerate reliable skill transfer while minimizing compensatory movements and injury risk.

Optimizing Grip Mechanics Evidence Based Assessment of Common Faults and Targeted Corrective Drills

Effective remediation begins with a standardized assessment protocol that seeks to optimize grip mechanics-interpreting “optimize” in the sense of making performance as effective as possible (see common dictionary definitions such as Dictionary.com and Britannica). Objective evaluation should combine visual inspection, palpation of hand placement, and simple quantitative checks (e.g., grip-pressure scale, clubface alignment at address). Use of slow-motion video (60-240 fps) and a brief battery of repeatable tasks (short chip, mid-iron half-swing, full-wedge swing) allows separation of grip-driven faults from downstream compensations. Clinicians and coaches should record baseline metrics and re-test after targeted interventions to document change over time.

Common mechanical faults are consistent across novice populations and can be reliably screened with simple observations:

- Excessive grip tension - forearms rigid, early release on downswing.

- Inconsistent hand placement – dominant hand too far under (strong) or on top (weak), producing face-angle bias.

- Incorrect thumb and V alignment – V’s not pointing to the trail shoulder leading to poor clubface control.

- Two-handed dominance on setup - lack of independent trail-hand control, poor wrist hinge.

Targeted corrective drills should be short, evidence-aligned, and progressive. Recommended interventions include: Towel Grip Drill (place a rolled towel under the trail forearm to promote connection and reduce grip tension); one-Handed Swings (lead-hand only drills for path and face awareness; trail-hand only for release control); and Grip-Pressure Feedback (use a 0-10 scale-target 4-6 during takeaway and transition). Progression: static holds → slow half-swings → tempoed full swings; re-introduce ball contact only after reproducible kinematic improvements. Empirically, interventions that isolate sensory feedback and reduce degrees of freedom yield faster motor learning in novices.

| Fault | Rapid Check | Target Drill |

|---|---|---|

| High grip tension | Forearm palpation during takeaway | Towel under forearm; 4-6 pressure focus |

| Weak/strong hand placement | V alignment check at address | Grip tape marker + one-hand swings |

| Poor wrist hinge control | Slow-motion hinge inspection | Lead-hand hinge + mirror feedback |

Monitoring: combine subjective ratings (player-reported comfort) with objective checks (video frames, contact pattern) at 2-4 week intervals to verify retention and transfer to on-course performance.

Establishing a Stable Stance and Footwork Patterns for Consistent Ball Striking

A reproducible base is a primary determinant of consistent ball contact; stability at the feet constrains kinematic variability upstream in the kinetic chain and reduces dispersion of clubhead impact location. Empirical work in motor control and sports biomechanics indicates that when novices adopt a stable relationship between center of pressure and base of support, club‑path and face‑angle variability decline and shot dispersion narrows. Practically, this means prioritizing predictable foot positions and small, controlled foot‑driven movements rather than large lateral slides that increase timing error. Emphasize posture that permits rotation around a stable axis: slight knee flex, a neutral spine, and a weight distribution that allows both rotation and dynamic balance.

Translate stability into concrete setup cues and measurable parameters. Coaches should teach the following simple, evidence‑aligned setup elements to novices:

- Stance width: shoulder width for mid‑irons; slightly wider for hybrids and woods to permit a longer radius of rotation.

- Weight distribution: start with ~50/50 on the feet, biased slightly toward the balls of the feet (not the toes) to enable rapid, controlled coil and recovery.

- Foot flare: toes slightly outward (~10-20°) to improve hip turn and reduce knee stress.

- Lower‑body tension: light engagement of glutes and ankles to stabilize against excessive lateral sway.

These simple prescriptions reduce novice variability and are inexpensive to coach and measure with basic observation or mobile video.

Footwork during the swing should prioritize rotational transfer of weight with minimal uncontrolled lateral displacement. Encourage a sequence of coil → rotation → recoil: the trail foot creates torque by loading the outer edge in the backswing, the lead foot anchors during transition, and a controlled weight transfer finishes toward the lead heel for solid compression. Useful, low‑risk drills include the step‑and‑set (step into the stance to build repeatable foot placement), the toe‑tap (small trail‑foot tap at transition to instill rotational feel), and the alignment‑stick under‑foot drill to cue consistent pressure path. These drills focus on timing and kinesthetic awareness rather than strength, which is appropriate for novice learners.

Adopt evidence‑based feedback and progressive practice to consolidate safe, repeatable footwork. Use slow‑motion video to quantify rotation and lateral sway, and, when available, pressure‑mapping or balance‑board data to show changes in center‑of‑pressure patterns as novices modify stance. progress from short, half‑swings to full swings and from static drills to hitting balls once the movement pattern is stable in practice. screen for ankle, hip, and thoracic mobility limitations-addressing these with mobility exercises reduces compensatory footwork that otherwise degrades strike quality and raises injury risk. consistent,measured practice of these elements reliably improves contact and reduces large miss‑patterns among beginners.

accurate Alignment and Targeting Strategies Using Visual and Instrumented Feedback

precise on-course performance begins with a reproducible relationship between the player, the club, and the intended line. Empirical evidence and coaching consensus indicate that errors in precision most frequently enough stem from inconsistent clubface orientation at address and during impact, rather than gross swing plane changes alone.Practically, this requires separating alignment into two controllable components: the geometric aim of the clubface relative to the target line and the kinematic alignment of the feet, hips, and shoulders. Adopting a consistent method for verifying both components reduces systematic lateral dispersion and fosters more reliable shot-shape control.

Visual strategies that sharpen targeting rely on hierarchical cueing: first set an intermediate visual anchor, then confirm the final target. Athletes benefit from fixing on a small, high-contrast point (a blade of grass, tee, or distant club) and using an immediate spot 1-3 yards in front of the ball to align feet and clubface. Suggested practice stimuli include:

- Alignment-rod drill – place a rod along the target line and practice addressing without touching the rod.

- Tee-point drill – use two tees to mark an intermediate aimpoint and a final aimpoint to train distance of focus.

- Perceptual narrowing – alternate between focusing on a near reference and the distant target to develop flexible fixation.

These drills enhance perceptual consistency and reduce common visual search errors observed in novice players.

Instrumented feedback complements visual training by supplying objective metrics that reveal hidden biases. Portable launch monitors quantify face angle, club path, and spin; high-speed video provides temporal and spatial frame-by-frame inspection; laser rangefinders and wearable IMUs corroborate distance and body kinematics. The table below summarizes practical instruments and thier primary contributions to alignment training.

| Instrument | Primary Metric | Practical Use |

|---|---|---|

| Launch monitor | Face angle & launch direction | quantify bias and link setup to ball flight |

| high-speed video | temporal clubface/stance alignment | Diagnose setup deviations and timing |

| Alignment rod / laser | visual aim confirmation | Immediate, low-tech validation of target line |

Designing an evidence-based practice progression requires alternating blocked repetitions with randomized target practice while integrating instrumented checkpoints. Begin sessions with 20-30 blocked shots using alignment aids to establish proprioceptive memory, then shift to shorter randomized bouts where the student must locate and execute to a novel target. Record key variables-face-to-path at impact, lateral dispersion, and perceived aim-across sessions to detect trends. emphasize that instruments are diagnostic, not prescriptive: cultivate the player’s intrinsic visual-motor calibration alongside technological feedback to achieve durable, transferable accuracy.

Postural biomechanics for Injury Prevention and Power Development Through Mobility and Core Engagement

Effective standing alignment establishes the mechanical foundation from which power is generated and injuries are averted. Maintaining a neutral lumbar curve with a mildly anteriorly tipped pelvis enables force transfer through the hips rather than excessive loading of the lumbar intervertebral joints. Similarly, a balanced shoulder girdle-neither excessively protracted nor depressed-preserves scapulothoracic rhythm and reduces compensatory lumbar or cervical motion during the swing. Optimal weight distribution (approximately 55/45 lead/trail at setup for novices progressing to a dynamic shift) and a slightly flexed knee posture produce an athletic base that promotes both stability and the capacity to generate ground reaction forces into the kinetic chain.

Mobility deficits commonly masquerade as postural faults and precipitate inefficient compensations. Targeted increases in segmental mobility restore ranges necessary for a full, safe rotation and powerful sequencing. Key mobility priorities include thoracic rotation, hip axial rotation, and ankle dorsiflexion, implemented through specific drills such as:

- Thoracic twist with band – enhances mid‑back rotation while maintaining lumbar neutrality;

- Half‑kneeling hip internal/external rotation – re-establishes lead‑hip turn without lumbar torque;

- Weight‑bearing ankle mobilization - ensures proper lower limb absorption and extension during transition.

These interventions should be prescribed relative to the golfer’s segmental stiffness profile and integrated into warm‑ups and the weekly training plan.

Core engagement is not synonymous with maximal abdominal contraction; it is indeed a coordinated, breathing‑informed strategy that stabilizes the spine while permitting efficient rotational power. Use a model of diaphragmatic inhalation followed by submaximal bracing to recruit the transverse abdominis and obliques as an anti‑extension and anti‑rotation corset. The following compact table summarizes practical postural cues, objectives, and brief drills that translate to the swing in novice populations:

| Postural Cue | Objective | Sample drill |

|---|---|---|

| Neutral pelvis | Protect lumbar spine | pelvic tilt awareness on wall |

| Thoracic turn | Increase swing arc | Seated band rotations |

| Diaphragmatic brace | Spinal stability with rotation | Inhale‑brace‑press progression |

Translating postural and core strategies into the dynamic swing requires progressive loading and explicit motor‑control cues. novices benefit from constrained practice that decouples rotation from lateral bending (e.g., slow‑motion swings with pause at top), and incremental tempo increases as mobility and bracing coordination improve. Emphasize measurable markers-range of rotation, single‑leg balance time, and a consistent inhalation‑brace sequence-so that training adaptations can be objectively tracked. adopt conservative workload progression and include restorative sessions (mobility + low‑intensity stability) to minimize cumulative tissue stress while maximizing the conversion of postural control into clubhead speed and injury resilience.

Correcting Swing Path and Clubface Control Through Kinematic Sequencing and Motor Learning Interventions

Kinematic sequencing underpins consistent club-path geometry and face orientation at impact.Faults in the proximal-to-distal order (hips → torso → shoulders → arms → club) create compensatory motions that manifest as open/closed clubfaces and out-to-in or in-to-out paths. Empirical studies of segmented motion show that restoring the temporal order of rotations reduces early or late release of the club, thereby stabilizing the face angle through impact. In practice, this means coaching cues that emphasize the initiation of rotation from the pelvis and trunk rather than the hands or arms, and measuring outcomes with simple metrics (ball flight curvature, impact tape, launch monitor face angle).

Motor-learning principles guide how sequencing is learned and transferred to on-course performance.Interventions that favor an external focus, induce variability in task constraints, and reduce prescriptive augmented feedback improve retention and transfer compared with internal, high-frequency feedback. Techniques such as differential practice (systematic variation), random practice schedules, and implicit learning strategies (analogy cues) facilitate robust motor programs for face control and path consistency.Recommended practice qualities include:

- External focus cues (e.g., “brush the grass toward the target”)

- Variable contexts (different targets, lies, and clubs)

- Reduced feedback frequency (summary or bandwidth feedback)

These elements help novices form adaptable timing patterns rather than brittle, consciously controlled motions.

Combine sequencing drills with motor-learning-informed progressions to accelerate improvements. Representative drills include:

- Hip-to-shoulder rotation drill – slow, exaggerated pelvis lead to feel segmental timing;

- Impact-bag or towel-palm drill – promotes late release and square face at impact;

- Step-through drill – enforces pivot initiation and natural distal whip;

- Metronome-synced half-swings – stabilizes tempo while preserving sequence.

Use augmented devices sparingly: brief video clips or launch-monitor snapshots for intermittent feedback are sufficient; avoid continuous, prescriptive verbal corrections that induce internal focus and disrupt automatic sequencing.

Structure sessions with a deliberate progression from controlled sequencing to adaptable submission. Begin with segmentation and slow-motion acquisition, transition to variable-target practice with external cues, and conclude with low-feedback retention trials that simulate on-course conditions. A concise session template follows:

| Phase | Duration | Primary Intervention |

|---|---|---|

| Segmentation | 10-15 min | proximal-to-distal drills, slow reps |

| Integration | 15-20 min | variable practice, external focus |

| Assessment | 5-10 min | Retention trial, minimal feedback |

Monitor progress with objective markers (impact tape, dispersion patterns, face-angle consistency) and prioritize interventions that produce persistent improvements across retention tests rather than transient gains during coached practice.

Regulating Tempo and Rhythm with Evidence Based practice protocols and metronome Based Training

Consistent temporal structure in the golf swing is a robust predictor of repeatable ball contact and reduced biomechanical stress; empirical motor‑learning studies and kinematic analyses indicate that novices who stabilize swing rhythm produce less variability in clubhead speed and impact location. Regulating the cadence of the stroke reduces maladaptive compensations (excessive lateral sway, early extension) that increase injury risk and degrade performance. From a mechanistic standpoint, imposed temporal constraints simplify the coordination problem by constraining degrees of freedom, allowing the nervous system to select more consistent inter‑segmental timing patterns.

Effective training must follow evidence‑based principles: baseline assessment, progressive overload of temporal difficulty, scheduled variability, and fade‑out of explicit external cues. A typical protocol begins with objective baseline timing (video or wearable inertial sensor) and prescribes explicit metronome targets that aim to reestablish a stable backswing:downswing relationship. Key protocol elements include:

- Baseline measurement of swing duration and variability (3-5 swings averaged).

- Immediate acquisition phase with metronome pacing (10-15 minutes per session).

- Distributed practice across days with randomized contextual interference (varying clubs and targets).

- Fading of metronome to assess retention and transfer (no‑metronome trials after 1 and 2 weeks).

Metronome‑based interventions should be parameterized and progressed. Practical settings derive from the commonly observed pros’ ratio (approximately 3:1 backswing:downswing) and from measured baseline durations; for example, if a learner’s downswing is ~0.5 s, prescribe a backswing of ~1.5 s and set metronome pulses so that three beats correspond to the backswing and one beat to the downswing. A simple,evidence‑driven 3‑week progression is: week 1 (acquisition) – 3 sessions/week,10-15 min/session with continuous metronome; week 2 (consolidation) – introduce variability and partial fading (50% metronome‑paced swings); week 3 (transfer) – randomized practice,full fade,retention test. Use of an external rhythm (metronome) promotes automaticity and reduces reliance on conscious control,improving retention in both laboratory and field studies.

| Metronome Setting (BPM) | Beat Pattern | Intended Effect |

|---|---|---|

| 60 | 3 beats backswing : 1 beat downswing | Stabilize 3:1 ratio; slow tempo for technical learning |

| 80 | 2 beats : 1 beat | Medium tempo for rhythm integration and speed control |

| 100+ | 1.5 : 1 (approx.) | Speed emphasis with maintained timing cues |

Safety and measurement are integral: monitor perceived exertion, scintillation of low‑back symptoms, and acute fatigue; reduce volume if technique deteriorates. Objective progress should be tracked with simple metrics: standard deviation of swing duration, impact dispersion, and percentage of trials within target tempo window. For clinicians and coaches, combine metronome pacing with outcome‑oriented feedback (carry distance, dispersion) and schedule follow‑up retention and transfer trials to confirm durable learning rather than short‑term performance gains-this alignment with motor‑learning evidence maximizes both safety and functional improvement.

Ball Position and Short Game Proficiency Context Specific Placement Guidelines and High Yield Short Game Techniques

Consistent contact and predictable trajectory begin with deliberate placement of the ball relative to the stance and selected club. As a general, evidence-aligned rule: place the ball progressively more forward as club length increases to preserve the intended attack angle and loft at impact – e.g., driver near the lead heel, long irons just forward of center, mid‑irons near center, and short irons/wedges slightly back of center to promote a steeper, compressed blow. Small positional shifts (one to two ball diameters) systematically change launch angle and spin; therefore, treat ball position as a primary control variable when refining shot shape or managing turf interaction rather than an aesthetic detail.

Technical cues for the short game should be succinct and repeatable.Prioritize three high‑yield elements at address: hands forward relative to the ball, weight on the front foot (approximately 60-70% for most chips and pitches), and a narrow, stable stance to limit lower‑body sway. For different shot intents, vary only a single parameter: for low bump-and-run keep hands markedly forward and minimize wrist hinge; for soft lob shots open the face, widen stance slightly, and increase wrist hinge to utilize bounce. Implement these cues in a structured practice set to convert them from conscious strategy to automatic motor patterns.

Contextual adjustments to ball placement and technique improve both safety and performance across variable lies. Make these pragmatic, evidence-driven modifications: for uphill lies move the ball slightly forward to permit cleaner contact; for downhill lies move it back to reduce excessive loft and thin shots; for tight fairway lies favor a slightly forward position and a controlled, descending strike to avoid bladed shots. To protect the wrist and lower back, avoid extreme forward lean with the shoulders or compensatory excessive wrist flexion; instead, rely on stance and weight distribution to produce the intended attack angle and reduce undue joint loading.

Adopt concise, repeatable practice drills and track simple metrics that reflect improvement. Useful drills include:

- Landing‑spot drill: place a cloth or target 10-20 yards away and practice varying swing length to hit the same landing spot;

- coin drill: remove a coin from under the back of the ball after impact to reinforce forward‑shaft lean and toe‑down contact;

- Clock‑face swings: repeat swings at 7, 9, and 11 o’clock to calibrate distance control for pitches.

use the following quick reference when experimenting on the range:

| Club | Ball position | Shot objective |

|---|---|---|

| Driver | Inside lead heel | Max launch, shallow attack |

| 7‑Iron | Center‑slightly forward | Controlled trajectory |

| Wedge | Back of center | Steep contact, spin control |

| Chip/Pitch | Back to center (depending on bump vs lob) | Landing spot precision |

| Putter | Centered to slightly forward | Consistent roll |

Q&A

Note on terminology

Q: The article title uses the word “Top.” What is meant by this term in the title?

A: In this context “Top” denotes a ranking - the highest-priority or most commonly observed items in a category. (General dictionary definitions characterize “top” as the highest place or part, or the foremost in rank or importance.) The phrase “Top Eight” therefore signals the eight most frequent or consequential novice errors addressed in the article.

Q: What is the scope and purpose of this Q&A?

A: This Q&A is intended to clarify the eight most common novice golf errors (grip, stance, alignment, posture, swing path, tempo, ball position, short game), to identify objective indicators that a problem exists, and to provide concise, evidence-informed corrective strategies, drills, and practice guidelines aimed at improving performance and reducing injury risk.

Overview

Q: What are the “top eight” novice golfing errors addressed here?

A: 1) Faulty grip; 2) Poor stance (base and balance); 3) Misalignment (aiming errors); 4) Incorrect posture (spine angle and joint flex); 5) Inefficient swing path; 6) Inconsistent tempo/rhythm; 7) Improper ball position; 8) Weak short-game fundamentals (chipping and putting).

Error-specific Q&A

1) Grip

Q: How does a faulty grip present and why is it significant?

A: A faulty grip commonly shows as an overly strong or weak hold, excessive tension in the hands/forearms, or incorrect placement of the club in the fingers. Grip determines clubface orientation through impact and strongly influences shot shape, consistency, and wrist/forearm load (injury risk).

Q: What evidence-based remedies and drills address grip problems?

A: - Aim for a neutral-to-slightly-weak grip for most players: V’s formed by thumb/index finger of each hand point between the trail shoulder and chin. – Place the club across the pads of the fingers (not too deep in the palms). – Reduce grip pressure to a firm-but-relaxed level (often described as 4-5/10). – drills: hold a towel under both armpits and make half-swings to learn coordinated forearm/hand action; practice hitting short shots with a glove or light shaft to feel correct placement. – monitor outcomes by checking face angle at address and typical initial ball flight; adjust gradually.

2) Stance (base and balance)

Q: What are common novice stance errors and their consequences?

A: Errors include stance too narrow or too wide, uneven weight distribution, and unstable foot placement. Consequences are loss of balance, poor sequencing of the swing, and inconsistent contact and distance control.

Q: What practical corrections and progression drills help?

A: – General guideline: shoulder-width for mid-irons; slightly narrower for wedges; progressively wider for long clubs/drivers.- aim for balanced weight distribution (approximately even at address for irons; slightly favor front foot for some irons at impact). – Drills: step-and-hit (start with feet together, step into stance as you swing) to train weight transfer; balance-board or single-leg posture holds (short duration) to develop stability. – Practice progressively: half-swings,3⁄4 swings,then full swings with attention to not compensating with excessive upper-body movement.

3) Alignment

Q: How do alignment errors appear and why do they matter?

A: Novices often aim body or clubface inconsistently-open/closed stance relative to target-resulting in predictable directional misses (slices or hooks). Accurate alignment is foundational for reproducible ball flight.Q: What are evidence-based alignment strategies and drills?

A: – Use alignment sticks (or a club) on the ground: one to indicate target line (clubface), another for foot/hip/shoulder line parallel to target line. – Pre-shot routine: pick an intermediate reference point on the ground 3-6 m in front of the ball and align clubface to that point, then set feet/hips parallel. – Drill: routine of placing a club on the ground along target line and practicing short controlled shots without moving the alignment aids. – Objective check: record setup from above/behind or have a partner check parallelism.

4) Posture

Q: What posture faults do novices exhibit and what are their effects?

A: Common faults include excessive spine tilt, rounded upper back, insufficient knee flex, and standing too tall over the ball. These reduce rotational capacity, create compensatory arm-only swings, and increase risk of poor contact and back strain.

Q: What corrective strategies and drills address posture?

A: – Set-up: knees slightly flexed, hinge from the hips to create a straight (neutral) spine angle, chest over the ball, shoulders relaxed. – Drill: ”wall hip-hinge” - stand a small distance from a wall and practice hip hinge without touching it; reinforces hip motion and prevents rounded upper back. – Drill: place a club along the spine of the left side (for right-handers) to feel neutral spine tilt and maintain that through slow swings. – Emphasize mobility and pre-practice dynamic warm-up to protect the lower back.

5) Swing path

Q: What are common swing-path errors and their observable outcomes?

A: Novices frequently swing outside-in producing slices, or excessively inside-out producing hooks. Other issues include steep/vertical takeaway or casting (early release). These errors lead to inconsistent directional control and poor energy transfer.

Q: What evidence-based interventions and drills improve swing path?

A: – Diagnostic: use slow-motion video to observe path; track initial ball flight relative to clubface. – Correction principles: encourage a one-piece takeaway,maintain wrist hinge to allow proper plane,and sequence lower-body rotation to start downswing.- Drills: gate drill (place two tees/clubs slightly wider than the clubhead to force correct path), L-to-L drill for proper wrist hinge and release timing, and “inside-out” path drill using a mid-line target for swing-surface awareness. – Progression: start with half-swings focusing on path, then lengthen as consistency improves.

6) Tempo and rhythm

Q: Why is inconsistent tempo a problem and how is it addressed?

A: Inconsistent tempo leads to erratic timing between body rotation, weight transfer, and club release, degrading contact quality and distance control. A repeatable tempo enhances reproducibility and feel.

Q: What practical, evidence-informed tempo strategies exist?

A: – Use ratios: many coaches recommend an approximate backswing-to-downswing time ratio of ~3:1 (backswing slower, downswing quicker) to promote timing. - Metronome or rhythm apps can train a consistent cadence. – Drills: count-based swings (“one-two-three” backswing, “one” downswing) or hit balls to a steady metronome set to a pleasant beat. – Emphasize consistency over absolute speed; power emerges from correct sequencing, not pure speed.

7) Ball position

Q: What ball-position errors do beginners make and what are the consequences?

A: Common mistakes include ball too far forward or back relative to club, causing mis-hits (topping, fat shots), undesirable launch angle, and poor spin characteristics.

Q: What are practical positioning rules and practice checks?

A: – Simple rules: ball slightly back of center for short irons/wedges; center for mid-irons; progressively forward as club loft decreases; driver placed off the inside of the lead heel. – Objective check: with feet together address a reference then step into intended stance to ensure repeatability; use alignment stick to mark correct spot. – Drill: play a series of shots moving ball one club-length forward/back to see how strike and flight change; internalize positions that produce clean contact.

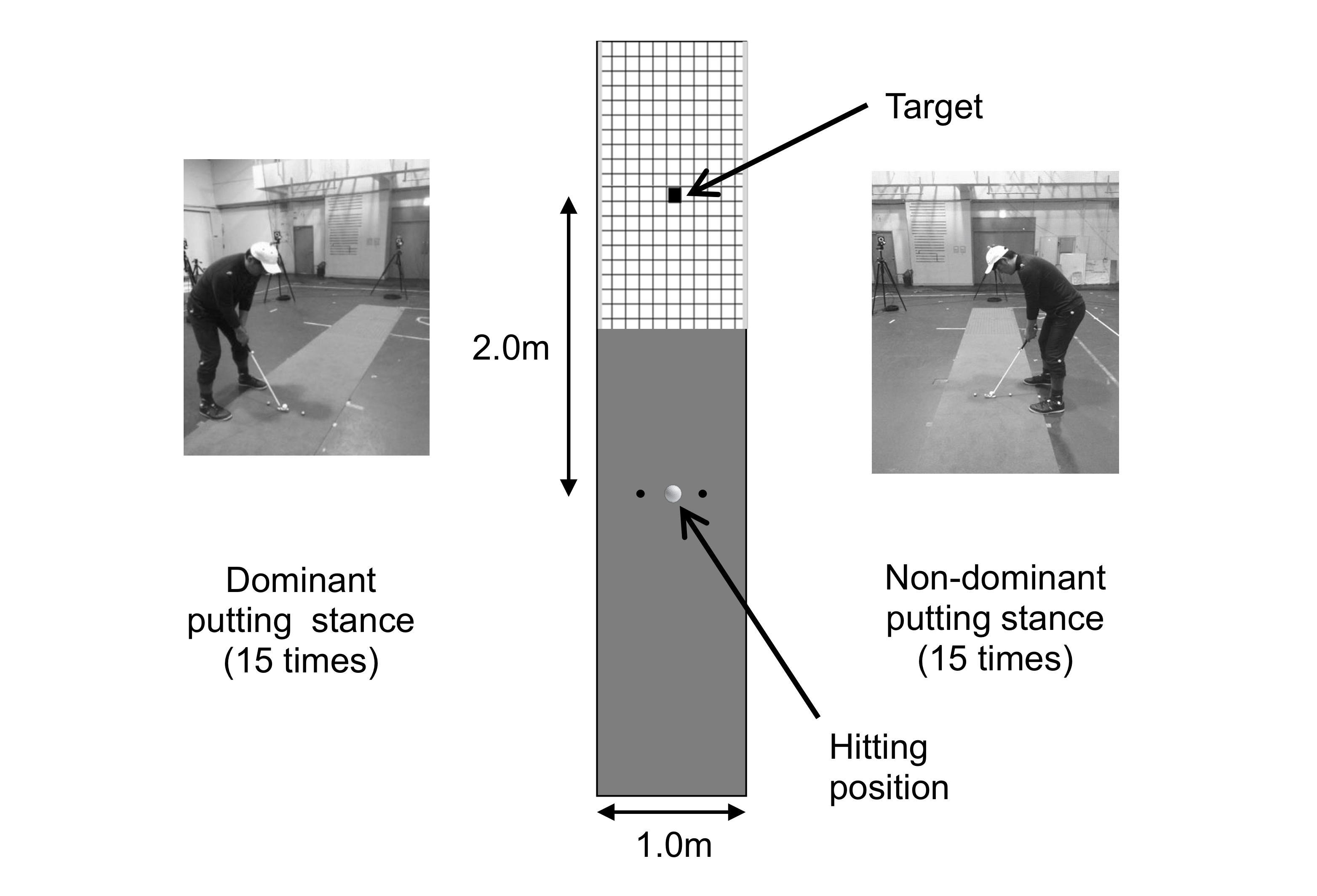

8) Short game (chipping and putting)

Q: What are common short-game deficiencies and their impacts?

A: Novices often use full-swing mechanics for chipping, grip the putter too tightly, or fail to control low-point and face angle. These lead to missed pars and variable proximity to the hole.

Q: What evidence-based fixes and drills improve short-game performance?

A: – Chipping: adopt a narrow stance, minimal wrist action, strike with a forward-leaning shaft so the club bottom brushes turf first; practice distance control via ”landing-spot” drills (pick and hit to specific landing points). – Putting: consistent set-up (eyes over ball, low grip pressure), short stable pendulum stroke using shoulders more than wrists, and stroke path drill (use gate or tee targets).- Drills: ladder drill for distance control (hit putts/chips to progressively farther targets),”up-and-down” simulation to practice pressure shots. – Emphasize green-reading and pace as much as technique.

Practice design, assessment, and injury prevention

Q: how should novices structure practice sessions to apply these remedies effectively?

A: - Begin with a brief dynamic warm-up and mobility exercises. – Focused practice blocks: one technical focus per session (e.g., grip+short swing; alignment+full swing). – Use blocked practice for initial motor learning (repetition of one technique) and switch to variable practice for transfer (vary clubs/targets). - include deliberate play: performance-oriented shots under modest pressure to simulate course conditions. – Limit high-volume full-swing practice in early stages to avoid overuse; integrate rest and cross-training.

Q: How can players objectively track progress?

A: – Record simple metrics: strike quality (toe/heel/center),dispersion (distance and direction),and launch/flight visible trends. – Use video periodically for setup and swing-path checks. – Keep a practice log noting drill, repetitions, outcomes, and perceived difficulty. – Seek periodic professional feedback for calibration.

Q: Are there safety considerations or common injury risks for novices making these corrections?

A: Yes. Rapid changes that increase forceful rotation or repetitive high-speed practice without conditioning can stress the lumbar spine, elbows, wrists, and shoulders. Prioritize mobility, core and hip strength, gradual load progression, and professional supervision when making major swing changes.

Final recommendations

Q: What is the overarching, evidence-informed approach a coach or novice should take?

A: Prioritize one or two high-impact setup elements first (grip and alignment), correct posture and balance, then address swing path and tempo progressively. Use objective feedback (video, alignment aids, ball flight), structured drills, and a practice schedule that balances repetition with variability. When in doubt, consult a certified instructor who can perform individualized assessment and prescribe a safe, efficient progression.

Q: Where should readers go for further,reliable guidance?

A: Consult certified teaching professionals (PGA/LPGA or national equivalents),peer-reviewed sports biomechanics literature for specific research,and reputable coaching resources for drill libraries and progressions.

the eight errors examined-grip, stance, alignment, posture, swing path, tempo, ball position, and short-game technique-constitute a coherent set of deficits that commonly distinguish novice golfers from more experienced players. Framing these issues within the conventional meaning of “novice” (i.e., an individual who is inexperienced in a task or activity) underscores that the patterns reviewed are characteristic of early-stage learning rather than fixed deficiencies. Each corrective strategy described in the article is grounded in principles of motor learning, biomechanics, and injury prevention, and where available, corroborated by empirical observation or controlled study.

For practitioners and instructors, the practical implications are threefold: prioritize fundamental motor patterns (safe, repeatable postures and grips) before adding complexity; employ progressive, evidence-based drills that balance technical correction with task variability to promote transfer; and monitor both performance metrics and physical load to mitigate injury risk. For learners, structured feedback-preferably from qualified instructors or validated video-analysis tools-combined with deliberately planned practice will accelerate skill acquisition more effectively than high-volume unguided repetition.

From a research viewpoint, ongoing work should quantify the relative efficacy of specific interventions across diverse novice populations, examine retention and transfer under ecologically valid conditions, and integrate wearable-sensor data to personalize corrective prescriptions. Clinically oriented studies should also further evaluate how technique modification impacts musculoskeletal load and long-term joint health.

Ultimately, treating novice errors as modifiable elements within a deliberate learning framework yields practical benefits for performance and safety. By applying the evidence-based remedies outlined here-within a structured, feedback-rich, and progressive coaching habitat-beginning golfers can achieve measurable improvement while minimizing the risk of injury, setting a sound foundation for continued development.

Top Eight Novice golfing Errors and Evidence-Based Remedies

Below are the eight most common mistakes made by novice golfers and practical, evidence-informed remedies to improve performance, lower scores, and reduce injury risk. Each section includes a short description of the error, why it matters (performance & injury), and concise, high-impact drills or training strategies backed by biomechanics and motor-learning principles used in modern golf instruction.

Quick Reference Table

| Error | Primary Effect | Evidence-Based Remedy |

|---|---|---|

| Grip | Poor clubface control | Neutral grip + towel drill |

| Stance | Balance & inconsistent contact | Feet-width & step drill |

| Alignment | Directional misses | Rail/club-on-ground routine |

| Posture | Loss of power + injury | Hinge-at-hips check + mirror |

| Swing Path | Slices & hooks | Gate drill + path feedback |

| Tempo | Timing breakdown | Metronome / 3-count swing |

| Ball Position | Launch inconsistencies | club-length chart + alignment |

| Short Game | Lost strokes around green | Contact drills + distance control practice |

1. Grip – Fault: Too weak/strong or inconsistent grip

Why it matters: grip is the single most influential contact factor. A poor grip alters clubface orientation at impact and increases shots that slice or hook. Good grip mechanics reduce compensations higher in the swing and decrease wrist/elbow strain.

Evidence-based remedies

- Adopt a neutral grip: place the club in the fingers (not the palm), create a V between thumb and forefinger pointing to your right shoulder (right-handed golfer).

- Towel-under-hands drill: place a folded towel under both palms while making half-swings to discourage excessive palming and promote finger hold.

- One-handed swings: make slow, smooth swings with the trail hand only to feel the clubhead and release.

- Use video feedback or mirror to ensure grip consistency before every shot – motor-learning research shows immediate visual feedback speeds acquisition.

2. Stance - Fault: Too narrow/wide or weight imbalance

Why it matters: A poor stance destabilizes the base of support, leading to inconsistent contact, topping, or heavy divots. Balanced stance supports rotational power while protecting lower back.

Evidence-based remedies

- Feet-width: use shoulder-width for irons, slightly wider for driver. This provides a stable rotational platform.

- Weight distribution: start with ~50-55% weight on the front foot for most full shots; maintain during setup and avoid excessive sway.

- Step-and-hit drill: address in target stance, step your lead foot closed/open as desired and hit; helps ingrain stable set-up through the swing.

- balance board or single-leg stability exercises in gym programs improve stance stability and transfer to better ball contact (supported by functional training principles).

3. Alignment - Fault: Aiming misaligned to target

Why it matters: Poor alignment is the silent score raiser; even a small misalignment across 200 yards can meen big misses. Without correct aim, a mechanically sound swing still produces poor results.

Evidence-based remedies

- Club-on-ground method: lay a club along the target line at ball level, then another club across your toes to align feet parallel to the target line.

- Rail drill: set two alignment sticks or clubs to create a “rail” and swing between them to reinforce correct aim and swing plane.

- Pre-shot routine: add an alignment check to every pre-shot routine – repetition builds automaticity per motor learning literature.

4. Posture – Fault: Rounded back or upright stance

Why it matters: Poor posture limits hip rotation and creates compensations in the lower back,shoulders,and wrists,increasing injury risk and sapping distance.

Evidence-based remedies

- Hinge at the hips: adopt a straight-ish back with a soft knee and hinge at the hips until your arms hang naturally. Use a wall to feel the hinge-stand with your butt near a wall and hinge forward while keeping contact.

- Posture-check mirror drill: use a full-length mirror or record setup to ensure a neutral spine angle.

- improve thoracic mobility and hip rotation through simple dynamic warm-ups (standing thoracic rotations, hip openers). Studies on golf biomechanics stress rotational mobility for power and injury prevention.

5. Swing Path – Fault: Over-the-top (slice) or inside-out (hook)

Why it matters: Swing path dictates shot shape. Novice golfers frequently enough compensate with hands or grip when path is off, worsening consistency and increasing strain.

Evidence-based remedies

- Gate drill: place two tees or small cones slightly wider then the clubhead at impact zone; swing slowly through the gate to encourage correct path.

- Path-feedback tools: use alignment sticks, foam targets, or a draw-fade visual aid to give immediate feedback on path.

- Slow-motion swings with video: record downswing to check clubhead trajectory; motor learning favors slowed practice plus variable speeds to transfer to full swings.

6. Tempo - Fault: Rushing takeaway or quick transition

Why it matters: Tempo controls timing. A rushed swing disrupts the kinetic chain, reduces transfer of energy, and increases errant shots and joint stress.

Evidence-based remedies

- Metronome training: use a metronome app set to a comfortable beat (e.g., 60-70 bpm) and synchronize takeaway, transition, and impact to a consistent rhythm.

- 3-count swing routine: “1 (takeaway), 2 (top), 3 (impact/finish)” – simple verbal cues aid consistency until tempo is internalized.

- Practice with partial swings: alternating 50%, 75%, and full swings builds tempo control and timing (variable practice enhances retention).

7. Ball Position – Fault: Ball too far back/forward for club

Why it matters: Ball position influences launch angle, spin, and strike location on the clubface. Misplacement reduces predictability and can cause fat/thin strikes.

Evidence-based remedies

- Club-length guide: for short irons, ball in centre of stance; mid-irons slightly forward of center; long irons and hybrid one ball inside lead heel; driver off lead heel. Use consistent setup markers on shoes or mat.

- Impact tape / face spray feedback: use to see where you strike the face and fine-tune ball position to achieve center-face impact.

- Simple alignment drill: place a tee behind the ball at the target side of the clubface to check that you hit slightly forward of the center for penetrating flight with irons.

8.Short Game – Fault: Poor distance control, inconsistent contact

Why it matters: The short game (chipping, pitching, and putting) accounts for the majority of strokes inside 100 yards. Novices frequently enough spend too much time on full swings and neglect scoring shots.

Evidence-based remedies

- Contact-focused drills: place a towel a few inches behind the ball during chip practice to prevent steep,fat shots and encourage downward strike on chips.

- Distance ladder drill: lay out targets at 5-10 yard increments and practice landing-zone control for pitches and chips – intentional, repetitive, variable-distance practice improves motor adaptation.

- Putting routine and green-reading: use a pre-putt routine (alignment, practice stroke, breathe) and practice uphill/downhill read variations. Use short putt drills (gate or tees) to boost confidence and mechanics under pressure.

Practical Beginner Practice Plan (Weekly)

Evidence supports structured, varied, and feedback-rich practice over mindless repetition. Below is a simple weekly plan for novices to build fundamentals efficiently.

- 2 sessions of full-swing practice (45-60 minutes each): focus on grip, stance, alignment, and tempo drills with video checks.

- 3 short-session blocks (20-30 minutes each): one chipping/pitching session, one putting session, one targeted swing-path work.

- 1 mobility & strength session (30 minutes): hip mobility,thoracic rotation,glute activation,and core stability to support posture and prevent injury.

- Daily 5-10 minute pre-round routine: dynamic warm-up and a few swings to groove tempo before play.

Simple progress metrics

- Track fairways hit, greens in regulation, and up-and-down percentage for short-game progress.

- Use video once every two weeks to compare setup and swing-visual feedback aids faster correction.

Injury Prevention Tips

- Warm-up: dynamic stretches and 5-10 practice swings raise muscle temperature and reduce injury risk.

- Strength & mobility: focus on rotational power (obliques,glutes),hip mobility,and thoracic extension to support posture and reduce lower-back strain.

- Rest and recovery: avoid high-volume repetitive practice without recovery; pain is an early warning-modify technique and see a professional if pain persists.

Case Study – Typical Novice to Solid Amateur

Scenario: A right-handed beginner struggled with a slice and inconsistent contact. Coach used a 4-week focused program: week 1 grip and stance drills; week 2 alignment and ball position; week 3 tempo/metronome training; week 4 short game ladder and pressure putting.With video feedback and daily 10-minute drills, the player reduced slice severity, hit more fairways, and improved up-and-down rate from 30% to 55% over two months.

Lesson: Small, targeted changes practiced with consistent feedback and progressive overload lead to measurable improvement.

Benefits & Quick Practical Tips

- Prioritize fundamentals first: a stable grip, posture, and alignment provide the foundation for swing improvements.

- Quality over quantity: 20 minutes of focused, feedback-rich practice beats 2 hours of unfocused swinging.

- Use tools for immediate feedback: alignment sticks, impact spray, metronome apps, and slow-motion video are inexpensive and effective.

- Keep a practice log: note drills, outcomes, and feelings to track what works and accelerate learning.

Additional Resources

- Titleist Performance Institute (TPI) assessments for mobility and swing blueprinting.

- PGA/LPGA beginner lesson resources and certified instructors for personalized, injury-aware coaching.

- Motor learning literature (variable practice, external focus cues) to structure practice effectively.

If you want,I can generate a printable 4-week drill schedule tailored to your current handicap and practice availability,or create short video-scripted drills you can record and compare. Tell me your current ball flight tendencies and practice time per week and I’ll customize a plan.