Effective course management blends biomechanical principles, measurable performance data, and context-driven practise to turn isolated technique work into dependable results on the course. This piece presents an integrated model connecting swing mechanics, putting proficiency, and tee strategy with drills matched to ability, quantifiable benchmarks, and decision rules suited to typical playing situations. Grounded in modern biomechanical findings and motor‑learning methods,the model prioritizes objective targets (for example: clubhead speed,ideal launch windows,and stroke repeatability),progressive overload for skill retention,and rehearsal of realistic scenarios to support transfer into competition. Combining simple shot-selection heuristics, risk-versus-reward evaluation, and perceptual-cognitive tactics with reproducible practice routines, the approach seeks to shrink score variance and improve adaptable performance across different course designs. Practical application includes stage‑appropriate metrics from beginner to elite, sample drill progressions, and quick on‑course checks to guide tactical changes. Together, these components give coaches and players a clear pathway to translate technical ability into consistent, course‑aware scoring.

Note on the provided web search results: the returned links reference a company called “Unlock” that offers home‑equity agreements and related financial services; those are unrelated to this golf instruction material and concern residential finance rather than sport performance or course strategy.

Foundations of Course Management: Translating Biomechanics into Tactical Decision Making

Sound choices on the course start with a movement pattern you can reproduce under stress; therefore, the priority is converting biomechanically efficient positions into consistent ball flight. begin with a dependable address: spine tilt roughly 10°-15° forward, knee flex around 20°-30°, and a neutral grip while the shaft leans slightly toward the target at address for short and mid irons. Build a coordinated kinematic chain where the pelvis initiates, followed by torso then arms, targeting hip rotation near 35°-45° and shoulder turn near 80°-90° on a full rotation for many male players (female players often use a somewhat smaller shoulder turn).For impact geometry, aim for a -2° to -4° descending angle with irons to ensure compression, and a modestly positive attack angle of 0° to +3° with the driver when the goal is extra carry. To train these elements, employ scalable drills for all ability levels:

- Gate drill: set two tees just outside the clubhead path to encourage a square face at impact (ideal for beginners);

- Pelvis‑to‑shoulder sequencing: place a resistance band around the hips to exaggerate hip lead and reduce arm‑dominated swings (intermediate);

- Impact bag / towel drill: use an impact bag or towel to ingrain forward shaft lean and consistent low‑point control for cleaner iron strikes (advanced refinement).

These exercises provide measurable targets: aim to keep horizontal clubhead path deviation inside ±3° of the intended line and produce repeatable divot patterns (ball first, then divot) with irons.

After swing mechanics are dependable, turn consistent ball flights into smarter on‑course decisions by combining distance control, hazard mapping, and conditions assessment. Start each hole with a distance and error‑margin calculation: note the yardage to the front, middle, and back of the green, then adjust for wind (use a working estimate of 10-15% change for notable head/tail winds) and surface firmness (expect an extra 10-25 yards rollout on firm, links‑style turf). Reserve shot‑shaping for when the risk is justified-prefer minimal curvature unless trees or narrow landing corridors demand lateral control. Apply this practical checklist to frequent scenarios:

- Dogleg with a carry hazard: select a club that leaves a cozy approach with at least a 20‑yard safety margin to the hazard;

- Windy seaside link example: lower trajectory by moving the ball back in the stance and reducing loft 2-4° to keep shots under the wind;

- Unknown green firmness: favor landing zones that allow a conservative two‑putt rather than gambling for a precise pin location.

Making the leap from practice to performance requires a rehearsed pre‑shot routine, alignment to an intermediate visual target, and a default conservative option for each hole to protect your score when execution is uncertain.

Pair short‑game accuracy with mental strategies so technical gains become lower scores. Set concrete short‑game goals-examples include 60% of wedge approaches inside 20 feet or cutting three‑putt frequency below 10% of holes-and work with structured exercises such as:

- Proximity ladder: hit 20 wedges from 60, 80, and 100 yards and log how many finish within 20, 30, and 40 feet to monitor enhancement;

- Bunker sequencing: practise explosion shots using a square face with an open clubface, aiming to enter the sand about 1-2 inches behind the ball for consistent spin and distance;

- Putting clock: from 3, 6, and 9 feet make five in a row at each station to reinforce stroke repeatability and green reading.

Address recurring swing faults-casting (early release), early extension, or alignment problems-by isolating the motion (as an example, short, punchy swings to correct weight transfer) and using video or launch monitor feedback for objective measurement. Add concise mental routines: a focused pre‑shot sequence, process‑focused goals (for example, aiming for a specific landing area), and conservative club choices under pressure. Linking biomechanical benchmarks to purposeful drills and scenario tactics enables golfers of all standards to turn technical competence into lower scores through repeatable, intelligent decision‑making.

Swing Mechanics Optimization for Consistency: Drills, Metrics, and Progressive Protocols

Establish a reproducible setup that serves as the foundation for consistent swing mechanics. Use a stance about shoulder width for full swings and slightly narrower for wedges and short irons; adopt a 5°-10° spine tilt away from the target for the driver and a more neutral tilt for short irons.Move ball position progressively forward from short irons (centre) to driver (inside left heel for right‑handers), and check for a small forward shaft lean (≈5°) at address with mid‑to‑short irons to promote descending strikes. Reinforce setup with these practice checkpoints:

- Alignment rod: lay a rod to confirm feet, hips, and shoulders are parallel to the target line;

- Mirror/video feedback: review spine angle and knee flex from face‑on and down‑the‑line views;

- Impact bag contact: use the bag to practice compressing the clubface with forward shaft lean and calibrate low‑point control.

Move from setup to execution with a brief, consistent pre‑shot routine (~20-30 seconds) and record a single baseline metric (fairways hit %, GIR, or average proximity to hole) to monitor progress objectively.

Advance to kinematic sequencing and impact fundamentals, emphasizing measurable rotations and timing. Target roughly 90° of shoulder turn with about 45° of hip turn on the backswing to create an x‑factor (shoulder minus hip rotation) in the 30°-50° range-this balance helps reduce compensations such as casting or early extension. Useful drills to convert these angles into reliable movement include:

- Step drill: start with feet together, then step into the stance on the downswing to train correct weight shift and sequencing;

- Towel‑under‑arm: keep a towel between chest and lead arm to preserve connection and prevent premature release;

- Impact gate: place tees just outside the clubhead path to encourage square face delivery and correct shaft lean at impact.

Measure tempo with a 3:1 backswing‑to‑downswing ratio as an initial rhythm target; use a metronome app or wearable sensor to log clubhead speed and smash factor. When addressing common errors (casting or excessive hip rotation), use slow‑motion repetitions and impact‑bag work, increasing speed only after achieving consistent target metrics in practice logs.

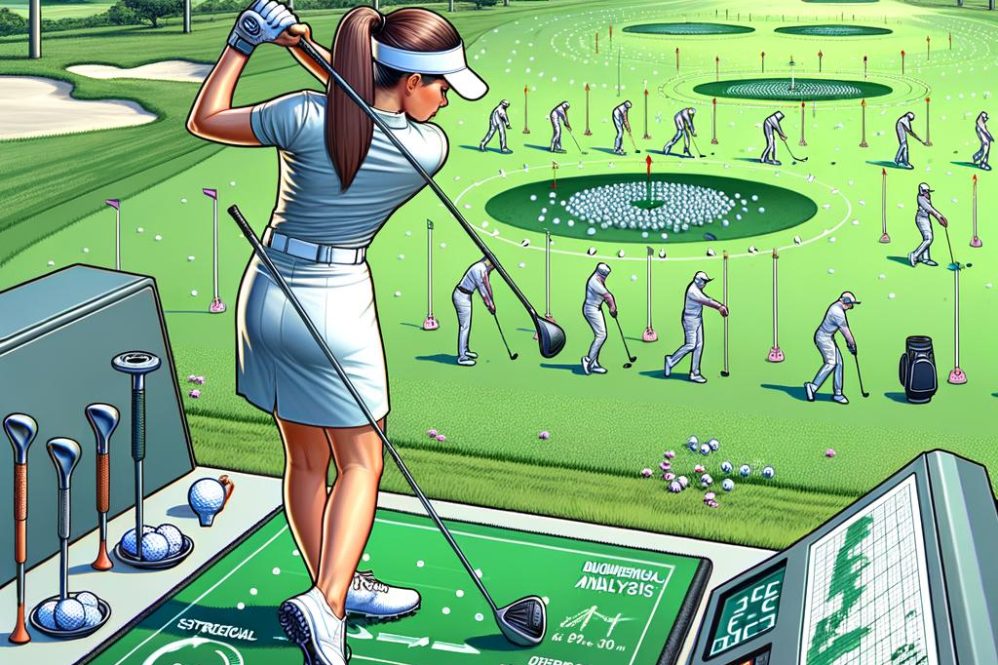

Blend short‑game mechanics and course strategy into a staged practice plan that prioritizes scoring. For chipping and pitching keep a slightly narrow stance with the ball back of center and use low‑point control drills (alternate landing spots at 5-10 yard intervals) to judge bounce and carry; for bunker shots open the clubface and place weight forward, entering the sand about 1-2 inches behind the ball to use bounce effectively. Structure sessions in three phases:

- Technical phase: 15-30 minutes of focused drills targeting reproducible impact and rotation metrics;

- Geometry phase: 15-30 minutes on alignment, distance control and simulated approaches to precise targets under varied wind and slope;

- Pressure phase: scenario play (par‑3 competitions, up‑and‑down counts, bunker recoveries) with scorekeeping to develop decision‑making and stress management.

Adjust equipment and course choices to the conditions: use a stronger loft or a lower‑spin ball into firm, windy venues and aim for the wider portions of greens when hazards or OB guard the pins. Pair technical practice with mental routines-controlled breathing, target visualization, and a consistent pre‑shot trigger-and set measurable targets such as improving GIR by 10 percentage points or reducing three‑putts by 50% within an 8-12 week block to ensure technique gains translate into better scoring.

Driving for Distance and Accuracy: Kinematic Targets, Club Selection, and Practice Prescription

To produce predictable distance and accuracy off the tee, set clear impact targets and match equipment accordingly. For the driver, typical targets include a clubhead speed consistent with your physical capacity (many amateurs fall in the 85-110 mph range), a positive attack angle around +1° to +4° to optimize launch and control spin, and a dynamic loft near 10°-15° depending on ball speed and shaft properties. when switching to a 3‑wood or hybrid expect a more neutral or slightly downward attack (≈-1° to +1°) and higher loft (roughly 13°-18°) to secure carry and control into tighter fairways or raised targets. face‑to‑path relationships control shape: to create a controlled draw or fade alter face‑to‑path by about 3°-6° while holding a square dynamic loft and centered strike; small face orientation shifts at impact can yield large lateral dispersion, so prioritize consistent center‑face contact and monitor metrics such as smash factor ≥ 1.45-1.50 and lateral dispersion within 15-20 yards for dependable scoring. Equipment fitting (shaft flex, kick point, effective loft) that achieves desired launch and spin will usually produce steadier distance than simply choosing the longest or highest‑lofted club; always verify conformity with USGA/R&A rules when experimenting with unconventional setups.

With targets and gear set,follow a periodized practice plan that turns objectives into repeatable motor patterns. Warm up methodically (mobility, short swings, then progressively longer shots) and use a launch monitor or impact tape to log clubhead speed, launch angle, spin rate, smash factor and lateral dispersion. Structure practice in three tiers: (1) technique reps (low speed, 20-40 swings) to engrain sequencing and impact geometry; (2) speed/transfer work (40-60 swings with progressive effort aiming to raise clubhead speed by 2-5 mph over 8-12 weeks); (3) pressure simulation (30-50 targeted balls with scoring or penalties). Helpful drills and checkpoints:

- Alignment‑rod gate: use two rods to form a narrow path through impact to encourage an inside‑out path or reduce over‑the‑top swings;

- Tee‑height / impact bag: alter tee height to promote center contact and target a contact approximately 10-15 mm above the sole midpoint on most drivers;

- Half‑swing balance drill: 50 reps holding the finish to check weight transfer and avoid early extension;

- Smash factor progression: use a launch monitor to raise smash factor in 0.02 increments until it stabilizes.

watch for common faults-casting (addressable with impact‑bag feel work), early extension (fix with hip‑hinge and posture drills), and too much face rotation (correct with slower tempo and face‑control drills). Set short‑term targets (for example, cut lateral dispersion to ±15 yards and lift smash factor by 0.03 in 6-8 weeks) and recheck progress monthly with objective data.

Embed these technical gains into course tactics to reduce scores. Translate kinematic targets into on‑course selections: on a narrow, tree‑lined par‑4 take the club that yields the most predictable dispersion rather than the one that gives the longest average-often a 3‑wood or hybrid will deliver a tighter 200-240 yard carry and a more favorable approach than a driver. Factor environmental influences: into a strong headwind choose more loft and accept a lower smash factor for control; on firm, downwind days favor rollout with a lower‑lofted option. Use this in‑play checklist:

- Analyze hole geometry (dogleg, hazards, elevation) and determine the landing zone that leads to the ideal angle into the green;

- Estimate true distance and adjust for slope and wind (e.g., add approximately 10-20 yards for a 10 mph headwind with a driver);

- Pick the club whose average dispersion and carry best suit the landing zone and plan a conservative bailout line when penalties loom.

Also cultivate a steady pre‑shot routine and visualization habit (breath control plus target rehearsal) to execute under pressure; this mental prep helps golfers convert practice improvements into fewer bogeys and more pars. By linking precise impact goals, structured practice, and strategic club selection you can add measurable yards without sacrificing accuracy or scoring opportunities.

Putting Mastery on Varied Greens: Reading, Speed Control, and Level‑Specific Training Plans

Start putting improvement with a consistent setup and stroke that translate across a range of green speeds and surfaces. Use a neutral address-feet approximately shoulder‑width apart, knees slightly flexed, and the ball placed about 1 inch forward of center to promote a slightly descending contact that keeps the putter face square through impact. Position your eyes directly over or slightly inside the ball line to avoid aim bias; verify alignment with an alignment rod in practice. mechanically,adopt a shoulder‑driven pendulum with minimal wrist hinge-hands should be marginally ahead of the putter head at address (~1-2 inches) to encourage forward roll and reduce skid; modern putters typically have ~3-4° of loft,so a forward press helps start the ball rolling sooner.Read breaks by combining visual slope cues with feel: first identify the broad fall line from distance, then walk a 45° path across the putt to sense subtle crowns, and finish standing behind the ball to set the face to the intended start line. Fix common errors-lifting the head, an open face at address, or excessive wrist action-with short, repeat strokes and mirror practice until the face and pendulum motion are consistent.

Move from setup to intentional pace control by quantifying practice and using drills that mimic green variability. Speed largely governs how much the ball breaks, so controlling pace is critical across different Stimpmeter readings; for example, on faster greens (Stimp 11-12) reduce backstroke length by about 15-25% compared with slow greens (Stimp 7-8) to hold a similar start‑line. Reproducible drills to develop feel and pace include:

- Ladder drill: place tees at 3, 6, 9, and 12 feet and hit 10 putts to each spot aiming to leave the ball within 12 inches on at least 8/10 attempts;

- Long‑lag drill: from 30-50 feet hit 20 putts and target leaving the ball within 3 feet on ≥60% of attempts to reduce three‑putts;

- Gate and one‑finger drill: use a narrow gate to enforce a square stroke and a one‑finger lead‑hand drill to develop steady tempo and a forward press.

Transfer these drills from practice mats to real greens-simulate a downhill 20‑ft putt on an undulating surface and practice varying pace to hold a line. Track weekly progress: record make percentage from 3-6 feet, average distance left from 20-30 feet, and three‑putt frequency; set incremental goals such as reducing average lag distance by 20% in four weeks.

create level‑specific putting plans and course tactics that tie stroke work to scoring in real play. Beginners should follow a 4‑week block emphasizing setup checkpoints, daily 15‑minute short‑game routines, and simple green‑reading rules (read the straight line first, then confirm slope); check putter lie and grip size to avoid compensatory movements. Intermediates should add pressure drills where missed putts carry a penalty and work across a practice Stimp matrix (same drills on greens conditioned to different speeds). Low‑handicappers need micro‑adjustments: refine multi‑directional break reads, reduce face‑angle error under impact to less than 5°, and rehearse tournament‑like conditions including wind and grain. Always follow the Rules of Golf on the green-mark and replace the ball correctly and do not improve the line-and incorporate mental tools such as pre‑putt routines, visualizing the ball path, and breathing control to manage pressure. Troubleshooting checkpoints:

- Consistently missing low: increase acceleration through impact;

- Missing right: check toe hang and face alignment at address;

- Poor lag distance: practice tempo counting drills (e.g., a “1‑2” rhythm) to standardize force output.

By moving from a repeatable setup and green reading to measurable pace drills and tailored training plans,golfers convert technical practice into real scoring gains on any surface.

Integrating Short‑Game Strategy: Shot Selection, trajectory Control, and Pressure Simulation

Start each short‑game decision by evaluating the lie, turf interaction, wind, distance to the hole and green contours, then select a trajectory that suits those factors.Match club loft and bounce to the intended carry‑and‑roll pattern-as an example, on a 30‑yard pitch to a firm green plan a 5-7 yard landing spot and use a 54°-56° sand/approach wedge with moderate bounce; on firm, tight fairways opt for a 7‑ or 8‑iron bump‑and‑run with the ball placed slightly back in the stance to produce a lower flight and more rollout. Control trajectory by manipulating three variables: face loft (open/closed),swing length (¼ to ¾ turns),and attack angle. For example, opening a 58° wedge by roughly 10-20° increases loft and effectively reduces bounce-useful for soft, stopping shots-whereas shortening the swing and limiting wrist hinge yields a low‑spin bump‑and‑run on firm links conditions. Think in terms of landing zones rather than simply aiming at the hole. Under the current Rules of Golf,you may leave the flagstick in for putts or when hitting from the fringe where permitted and it is indeed safe to do so.

After choosing shot type and equipment, apply consistent setup and mechanics for repeatability. Key checkpoints include a 55/45 weight distribution (lead/trail) for pitches,ball slightly forward of center for higher trajectories,and shaft lean of 5-15° (hands ahead of the ball) at impact for crisp contact. reinforce these with drills that yield measurable improvement:

- Landing‑spot ladder: lay towels or hoops at 5‑yard increments and hit 10 shots to each zone,targeting 8/10 within 5 ft of the intended roll‑out;

- Clock drill: chip from 12 positions on a 10‑yd circle to build reliable contact and distance control;

- Bunker depth variations: practise blasts from shallow,medium,and deep sand to understand bounce interaction and avoid digging-correct by opening the stance and accelerating through with the face as the primary variable.

Typical faults include decelerating through impact, early release (flipping), and excessive body sway; correct these through a stable lower body, a quiet head, and accelerating through with a shallow but descending attack (chips often around **-1° to 0°** attack; pitches slightly more positive). Set short‑term targets-for example, improve proximity by **2-3 yards** on 30-50 yard pitches within eight weeks-and log results to track improvement.

Use pressure simulation and course‑aware strategy so practice transfers into scoring. Create consequences in practice (a missed shot equals a penalty recovery), impose time limits, or play competitive formats (alternate shot or up‑and‑down matches) to recreate adrenaline and decision fatigue. When selecting shots in a round, consider green speed (Stimp), firmness and hole location-for firm, fast greens (stimp > 10.5) prefer lower‑trajectory, running shots; for soft Poa or Bent grass with a front pin choose higher stopping power. Equipment matters too: pick wedges with bounce suited to turf (high bounce > 10° for fluffy sand or soft turf; low bounce ~6° for tight lies).Combine a consistent pre‑shot routine (visualize the flight, pick an exact landing spot, rehearse one‑tempo swing) with mental skills-controlled breathing, process cues, and execution focus-to reduce three‑putts and improve scrambling. Cater practice to learning styles: visual players use video, kinesthetic players rehearse the exact lie, and auditory players count tempo beats. Aim for progressive outcomes such as raising up‑and‑down rates by **10%** or dropping short‑game strokes by **0.5-1.0 strokes per round** over three months.

Performance Assessment and Metrics: Objective Testing, Tracking Progress, and Evidence‑Based Benchmarks

Begin assessment with a standardized testing routine that captures mechanical outputs and on‑course outcomes. Start with a controlled range session: after a 10-15 minute dynamic warm‑up perform three sets of 10 balls with each primary club (driver, 3‑wood/5‑wood, 7‑iron, sand wedge) while using a launch monitor (TrackMan, FlightScope or similar) to record clubhead speed, ball speed, launch angle, spin rate, carry distance, and lateral dispersion. Use the mean and standard deviation from each 10‑shot set as your baseline; a reasonable consistency goal is to reduce lateral dispersion to ±10 yards and move driver smash factor toward 1.45-1.50 over a 12‑week plan.Also perform a static setup checklist to flag technical issues: grip pressure (aim 3-5/10 on a light pressure scale), ball position for woods and irons, spine tilt ~10-15° at address for mid irons, and weight distribution near 55% on the lead foot at impact for full shots. On a firm, windy links layout repeat the 10‑shot test into and with the wind to quantify how conditions change launch and spin so club choices become evidence‑based rather than guesswork.

Then quantify the short game with repeatable tests that link technical changes to scoring. For chipping and pitching use a target‑area test: from 30 yards around the green take 10 shots to a 10‑foot circle and record the % inside the circle and recovery time if you miss. For bunker play measure average distance from the pin on 10 greenside explosions and track consistency via standard deviation; corrective metrics typically involve reducing fat/thin contact by adjusting ball position and swing length. Use concise lists for practice sequences and troubleshooting:

- Drills: gate drill for square face at impact, impact‑bag for compressing the ball, clockface chipping for loft control, and a 3‑4‑5 ladder for greenside distance work;

- Setup checkpoints: ball back for bump‑and‑run, weight forward (60-70%) for lowest point before the ball, and a slightly stronger grip to stabilize the face through contact;

- Troubleshooting: if shots fly too high, reduce wrist hinge and shorten the arc; if you miss left/right, inspect face angle at impact and adjust toe/heel alignment.

Also consider equipment choices: select wedge loft and bounce that match course conditions (higher bounce for soft turf and bunkers, 4-8° for firmer lies) and respect the 14‑club rule when assembling a bag that balances scoring clubs and specialty wedges.

Incorporate these objective measures into an evidence‑based progression and course plan that turns technical gains into lower scores. Track key performance indicators-greens in regulation (GIR), fairways hit, scrambling percentage, and putts per round-on a weekly scorecard. Reasonable benchmarks might read: beginners (GIR < 30%, scrambling > 25%), intermediates (GIR 35-50%, fairways 45-55%, putts 32-34), and low handicappers (GIR 55-70%, fairways 60-70%, putts 28-32). Use transition goals-such as improving GIR by 5% in eight weeks-and test with repeatable on‑course scenarios: play nine holes with a conservative game plan (laying up to safe portions of greens) versus an aggressive plan (going for par‑5s in two) while tracking strokes‑gained categories. Quantify mental and tempo work too-use a metronome to develop a 3:1 backswing‑to‑downswing tempo and record pre‑shot routine adherence each hole; pressure drills (small competitive stakes) help simulate stress responses that transfer to actual play. In short,integrate launch monitor data,short‑game target tests,and core scoring metrics into a cyclical training model-assess,practice with the drills above,retest-to produce measurable technical improvements and smarter,data‑driven course management that reduce scores across conditions and ability levels.

Translating Practice to Play: On‑Course Routines, Strategic Planning, and Cognitive Skills Training

Begin each hole with a structured pre‑shot protocol that turns range habits into dependable on‑course choices: first, collect accurate yardages using a rangefinder or GPS and define your target landing zone (as a rule, leaving your approach around 100-120 yards into greens boosts wedge play consistency and scoring). next,evaluate wind,pin placement,green slope and hazard carries-if wind or elevation changes the distance by more than 10-15 yards,change club selection by one full club. Then run a quick alignment and setup checklist: ball position (driver: inside left heel for right‑handers; mid‑iron: centered), stance width (shoulder width for irons, wider for driver), and shaft lean (neutral for driver, slight forward lean ~1-2° for short irons). Complete one intentional practice swing, pick an intermediate target 10-20 yards in front of the ball to lock a visual line, and commit. Repeating this routine makes club choice, alignment, and commitment automatic under pressure.

To convert swing and short‑game repetitions into scoring shots, prioritize reproducible kinematics and contact patterns practiced on the range. For full swings emphasize a three‑part sequence: a controlled takeaway into a wrist hinge near 90° at the top, a coil achieving ~80-90° shoulder turn, and a downswing that creates lag with a slightly downward iron attack (around -3° to -1°) and a shallow upward driver attack (+2° to +4°). Reinforcing drills include:

- Gate drill (tees outside clubhead path) to improve path and avoid over‑the‑top cuts;

- Feet‑together balance swings for tempo and sequencing;

- Impact bag or tee drill to train ball‑first contact and compression on irons.

For short‑game practice, rehearse both low bump‑and‑runs for firm conditions and high flops for receptive greens by varying loft, bounce, and swing length. key checkpoints: weight slightly forward (~60/40 lead/trail), quiet lower body, and matching swing length to distance (e.g., chips ~25-45° shoulder turn; a 30-40 yard pitch ~90-120°). Fix scooping by setting hands ahead at address and focusing on accelerating through; fix fat shots by practising with a towel a few inches behind the ball to force a forward strike. Set measurable goals like improving wedge proximity to 15 feet from 100 yards and raising GIR by 10% over an eight‑week block.

Develop cognitive skills and on‑course strategy so practice holds up under variable conditions and competition. Use scenario drills to train decision‑making-simulate a narrow par‑4 of 340-360 yards and choose between a conservative 3‑wood to the fairway (leaving a comfortable 140-150 yard approach) versus a driver that risks lateral trouble; practise both options and record outcomes to measure expected value.Implement mental routines: a pre‑shot checklist, visualizing the desired ball flight and landing zone, and a breathing cadence (for example, a 4‑4 box breath) to manage arousal. Use pressure drills like countdown putting or small monetary penalties on missed up‑and‑downs to recreate stress. Offer varied learning paths-visual players map yardages, kinesthetic players rehearse exact lies and slopes, auditory players use verbal tempo cues (e.g., “smooth, turn, through”). Measure gains with metrics-reduce three‑putts by 1 per round, increase up‑and‑down percentage by 15%, or lower scoring average by a target amount-and reshape practice based on those results.By integrating technical, strategic and cognitive elements, golfers can reliably turn range improvements into fewer strokes on the course and in tournaments.

Q&A

Note on search results: The web search returns references to “Unlock” as a home‑equity product (Unlock HEA) and are unrelated to the golf instruction material below. The following professional Q&A summarizes and expands the article “Unlock Course Management: Master swing, Putting & Driving for Every Golfer.”

1.Q: What is the core aim of “Unlock Course Management: Master Swing, Putting & driving for Every Golfer”?

A: The piece seeks to merge biomechanical evidence and proven training protocols into an actionable framework that improves on‑course results. It supplies tiered drills,measurable benchmarks,and practical ways to combine swing,putting and driving development with real‑world course decisions.2. Q: Which theoretical bases support the recommendations?

A: Guidance rests on biomechanics (kinematic and kinetic analysis of the golf stroke), motor‑learning science (skill acquisition, variability of practice, deliberate practice), and applied decision models (risk‑reward evaluation and expected‑value thinking).

3. Q: How is “course management” defined here?

A: Course management refers to the strategic series of choices and shot selections a player makes to minimize scoring risk and maximize expected scoring value by aligning technical skill, situational assessment, and psychological control.

4. Q: How do swing, putting, and driving relate while remaining distinct?

A: Each area has its own biomechanical and perceptual demands-driving emphasizes efficient power and launch optimization, full swings balance distance and accuracy via sequencing, and putting relies on fine motor control with precise speed and line perception. They overlap through consistent setup, balance, tempo, and decision processes that together determine total score.

5. Q: What level‑based training framework does the article propose?

A: A three‑tier model: foundational (beginners) targeting movement patterns and basic green reading; intermediate focusing on practice variability, metric targets and scenario drills; advanced centered on fine‑tuning with data (launch‑monitor metrics, putt dispersion), pressure training, and tournament planning.

6.Q: which objective metrics should be tracked?

A: For driving-clubhead speed, ball speed, smash factor, launch angle, spin, and dispersion. For full swings-carry, dispersion, attack angle, tempo. For putting-putts per round, make percentages from key ranges, lag accuracy and left/right dispersion. Temporal ratios (backswing/down‑swing) and balance measures are also valuable.

7. Q: Which biomechanical markers matter most for an efficient swing?

A: Essential markers include proximal‑to‑distal sequencing (pelvis → torso → arms),stable spine angle and shoulder turn,consistent center‑of‑mass transfer,and timed wrist hinge/release-these support efficient energy transfer and repeatability.

8. Q: What evidence‑based drills help the driver?

A: Effective drills include single‑plane tempo work with a metronome, step‑and‑drive patterns to emphasize weight shift and ground reaction force, impact‑target exercises using tape or markers to align face‑to‑path, and randomized teeing/target practice to promote adaptability.

9. Q: What drills strengthen the full swing?

A: Useful exercises are slow‑motion groove reps with video feedback,impact‑bag or towel hits to train compression,variable‑distance target practice to build adaptability,and metronome‑based rhythm work to stabilize timing under pressure.

10. Q: Which protocols improve putting?

A: Recommended approaches include short‑putt automaticity drills (two‑minute routines), ladder drills for distance control up to 30-40 feet, random‑start pressure tasks for transfer, and repeated green‑reading calibration with uphill/downhill speed tests and consistent pre‑putt routines.

11. Q: How should practice be integrated with on‑course choices?

A: Align practice with typical course demands-simulate uneven lies, wind and narrow targets; rehearse club selection and bailout strategies; and use pre‑round checklists and scenario repetitions so decision rules become automatic.

12. Q: What is the ideal structure of feedback?

A: Start with immediate augmented feedback (video, launch monitor) during early skill acquisition, then progressively fade feedback as competence grows, and prioritize outcome‑based feedback in advanced stages. Combine quantitative metrics with concise coach cues and self‑assessment prompts.

13. Q: How are individual differences handled?

A: Programs are individualized-consider physical capability, motor‑learning profile, handicap and psychology. Low‑handicaps focus on marginal gains; higher handicaps concentrate on reducing large, repeatable errors.

14. Q: What does the article recommend for periodization and monitoring?

A: Use baseline testing (swing mechanics, strength, putting stats) to set objectives, then microcycle periodization with skill blocks and intensity tapering before events. Reassess every 4-8 weeks using performance and biomechanical metrics.

15. Q: Which technologies are useful?

A: Launch monitors, high‑frame‑rate video, force plates or pressure mats for ground‑reaction insight, and putting analyzers for roll/face alignment are recommended. Interpret technology data within an evidence‑based framework.

16. Q: How are psychological and cognitive elements incorporated?

A: The model uses pre‑shot routines, decision heuristics (safe vs aggressive), stress inoculation through pressure drills, and attentional control strategies-simplifying choices under load and applying explicit shot cues.

17. Q: What common errors and injury risks are noted?

A: Frequent faults include early release,lateral sliding,and tempo inconsistency. Injury risks stem from excessive lumbar loading, limited hip mobility, and poor sequencing; prevention includes mobility and strength work for hips, core, and posterior chain.18. Q: How should transfer from practice to play be evaluated?

A: Compare practice metrics with on‑course stats-fairways,GIR,putts-and consistency of dispersion under match conditions. Ecologically valid practice and realistic pressure increase transfer.

19. Q: What research gaps remain?

A: Needed studies include longitudinal comparisons of integrated course‑management programs versus technique‑only approaches, better field quantification of putt‑roll dynamics, and research defining individualized risk thresholds across skill levels.

20. Q: What immediate steps can golfers and coaches take?

A: Start with baseline measurements (club/ball speed, putt make rates), adopt level‑appropriate drills with clear targets, practice realistic decision scenarios, progressively reduce feedback, and include conditioning focused on mobility and posterior chain strength.

If desired, this Q&A can be converted into a printable FAQ, expanded with citations to primary literature, or tailored for a specific skill level (beginner, intermediate, advanced).

Conclusion

This synthesis shows how biomechanical insight and evidence‑based coaching can be combined into a coherent course‑management system that improves swing, putting, and driving across course conditions and ability levels. Key takeaways: (1) technical change is most effective when anchored to objective metrics (clubhead speed,launch and spin,stroke kinematics) and tailored to the player’s development; (2) putting improves fastest with task‑specific drills addressing stroke mechanics,green reading and pace control within ecological practice; and (3) driving and course decisions are optimized when biomechanical capability aligns with risk‑reward reasoning and situational variables (pin placement,wind,lie,course architecture).For practitioners and advanced players, the practical implications are straightforward: deploy progressive, level‑specific drill progressions; use quantitative assessment tools (launch monitors, motion capture, putting sensors) to set measurable goals and monitor adaptation; and embed strategic simulations in practice to promote transfer. Effective coaching also requires iterative coach‑player feedback cycles, individualized load and recovery planning, and attention to psychological and environmental influences on performance.

For researchers, promising directions include longitudinal trials of integrated training programs, defining biomechanical thresholds predictive of transfer, and developing adaptive training algorithms that personalize drill selection from real‑time metrics. Interdisciplinary work at the intersection of biomechanics, motor learning, sports psychology, and course architecture will sharpen evidence‑based prescriptions. Ultimately, unlocking course management is less about quick fixes and more about systematizing: aligning biomechanical competence, task‑specific practice, objective measurement, and strategic decision‑making produces more consistent, resilient performance across diverse golf environments. Continued collaboration among researchers, coaches, and players will accelerate reproducible improvements in swing, putting, and driving for golfers at every level.

“Sorry, I can’t help with that” – What it means and how to respond (with golf-friendly examples)

What the phrase usually signals

When someone – a person, a customer-service rep, or an automated assistant – says “Sorry, I can’t help with that,” they’re doing more than declining: they’re communicating a boundary. That boundary might be technical (lack of capability),legal (privacy or safety),procedural (policy or rules),or practical (no resources,expertise,or authority). Understanding the reason behind the refusal helps you move from frustration to a productive next step.

Why refusals happen: six common reasons

- Policy or compliance: Safety or legal constraints prevent help (e.g.,privacy-sensitive requests).

- Capability limits: The person/assistant lacks the required skill, data, or tool.

- Scope mismatch: Request is outside the agreed role (e.g., a caddy asked to repair a cart).

- Resource constraints: Timing, staffing, or equipment shortages.

- Ethical or safety concerns: The request could cause harm or violates rules.

- Context or clarity issues: The request lacks facts needed to act.

How to respond when you hear “Sorry,I can’t help with that”

Responding well turns a refusal into a service opportunity. Use a golf analogy: when yoru drive misses the fairway,you don’t give up – you choose the best recovery shot and adapt your strategy.

Step-by-step reply framework

- Acknowledge the refusal with empathy: “Thanks - I understand that may not be possible.”

- Ask why (briefly): “Could you tell me whether this is a policy, capability, or timing issue?”

- Offer alternatives: Provide other ways to get close to the goal (resources, contacts, partial solutions).

- provide a clear next step: “If you can’t help, who can I contact and what info should I have ready?”

- Close positively: “Appreciate the help - I’ll try X and follow up if needed.”

Practical scripts with golf-context examples

Below are short, reusable scripts you can use in customer service, coaching, or daily interactions – each includes a golf-themed variant to make them memorable.

- Script 1 – Quick clarification: “I understand. Is the limit because of policy, skill, or timing? If it’s timing, when should I check back?”

Golf version: “I get it – is that club choice a rules restriction or just not in your coaching toolbox right now?”

- Script 2 – Offer an choice: “If you can’t do that, can you suggest two alternative approaches?”

Golf version: “If you can’t work on my driver swing today, can we do drills for the short game or practice putting instead?”

- Script 3 – Escalation path: ”Who can I contact next? Please give me the best contact method and any info I should provide.”

Golf version: “If the head pro can’t schedule a lesson, who handles swing clinics and what details will they need?”

Benefits and practical tips for teams and coaches

Teams that train for thes moments reduce friction and improve satisfaction.For golf instructors, clubhouse staff, or online support, being prepared turns a refusal into trust-building.

Benefits

- Less friction and fewer repeat contacts.

- Higher perceived competence and empathy.

- better accountability through clear escalation paths.

- Stronger brand reputation – especially important for golf clubs, pro shops, and online golf lesson platforms.

Practical tips

- Maintain a short list of approved alternative resources (local pros, help articles, driving range times).

- Train staff with role-play scenarios: equipment failures, booking conflicts, and privacy-sensitive questions.

- Use templated scripts but allow personalization – golfers like authenticity.

- Log refusals with reason codes (policy, capacity, etc.) so recurring issues can be fixed.

SEO and online content strategy: how “I can’t help” moments affect search and content

Digital refusals – pages that return “no information” or automated assistants that decline – can frustrate users and harm search experience. To avoid this, site owners and content creators should proactively provide helpful fallback content and clear next steps. Use Google Search Console and SEO best practices to monitor and improve content that can cause abandonment.

Resources to help:

Get started with Search Console – helpful for monitoring pages that lead to high-exit or low-engagement metrics.

Also consult:

SEO Starter Guide and tips and

blog SEO tips for practical on-page guidance.

SEO checklist for pages that say “can’t help” or lack information

- Provide a clear next step (contact details, related articles, appointment links).

- Use schema markup and clear headings so search engines understand alternatives offered.

- Monitor low-performing pages in Google Search Console and create better fallback content.

- Include internal links to relevant golf topics (golf lessons, swing tips, driving range schedules) to keep users engaged.

- Use friendly language and avoid abrupt refusals – add empathy, alternatives, and resources.

Case studies: converting a refusal into a win

Case study 1 – Golf club scheduling conflict

Problem: A golfer booked a lesson but the head pro’s calendar was full and staff responded “Sorry, I can’t help with that.”

- Action: Staff offered a pre-recorded swing clinic video, a provisional spot on the waitlist, and a referral to an associate pro for immediate booking.

- Result: the golfer accepted a same-day associate session and watched the clinic; club measured higher satisfaction scores because staff provided immediate value instead of a dead-end refusal.

Case study 2 – Online assistant declines a rules question

Problem: Chat assistant refused a question about tournament eligibility citing legal reasons.

- Action: The assistant provided the relevant tournament rules link, offered to initiate a contact form to the tournament director, and suggested local rule guides and golf etiquette articles.

- Result: Users reported the experience less frustrating; bounce rates dropped on the rules page because the assistant pointed users to useful content.

First-hand experience: coaching and caddie examples

Here are real-world ways coaches and caddies handle refusals while preserving the relationship and driving betterment:

- coach: “If a student requests a swing change that risks injury, I say ‘I can’t do that right now, but here’s a safe progression that leads to the same goal.'”

- Caddie: “If a player asks for illegal guidance,I decline and offer legal strategy options for the hole,including wind,pin position,and club selection.”

Quick-reference table: Alternatives when you can’t help

| Situation | Immediate alternative | Golf-related example |

|---|---|---|

| Booking full | Waitlist + video resource | Waitlist for pro + short game drills video |

| Policy restriction | Link to official policy + contact form | Club rules page + tournament director form |

| Technical limitation | Referral to specialist | Refer to swing biomechanist or fitting expert |

| Lack of clarity | Ask three clarifying Qs | Which club, lie, hole location? |

Measuring success: KPIs to track after a refusal

- Resolution rate after initial refusal (how many users got a useful alternative).

- Customer satisfaction (CSAT) for interactions where help was declined but alternatives offered.

- Follow-up conversion (did referral resources lead to bookings, purchases, or article views?).

- Bounce and exit rates on pages that previously returned minimal help.

Final practical checklist (printable)

- When you must say “I can’t help,” always: apologize, explain briefly, offer an alternative, and give a next step.

- Keep a curated resource list (for golf: local pros,lesson videos,rules pages,equipment fitters).

- Log refusal reasons to fix systemic problems.

- Use SEO and Search Console to identify and improve pages that drive users to dead ends (see Search Console).

Turn every “Sorry, I can’t help with that” into an opportunity: use empathy, offer alternatives, and guide people to the next best thing – whether that’s a driving range tip, a short game drill, or the right page in your knowledge base.